V

1

As a last-ditch effort to find work in Vienna, Jeanneret barged, unbidden, into the offices of the city’s two leading architects, Otto Wagner and Josef Hoffmann. Twenty-five years later, Le Corbusier claimed that Hoffmann offered him a job for two hundred crowns and introduced him to Klimt and other artists, but in a letter he wrote L’Eplattenier at the time he said that Hoffmann was not even in his office and that they never met.

L’Eplattenier advised his two students to go to Dresden or another major German city; Jeanneret responded, “You’re violent and treat us like ten-year-olds.”1 Jeanneret knew what he had to do: “In order to create a new art, you have to be in a position to calculate arches, large roof spans, bold cantilevers, in short everything our traditionalist ‘masters’ fail to do, for you can imagine that my ambition goes further than making little rental houses and villas.”2 He could not acquire this technical knowledge in the German language; besides, he needed to gain his living. He had made up his mind to move to Paris.

GEORGES AND MARIE were enraged. They were upset both by the idea of Edouard’s going to the French capital and his failure to communicate with them directly. He responded that there had been no point in explaining the decision to them since they did not even know the names of important architects.

He then pinned his secrecy on his reluctance to trouble them: “That would have made a constant disturbance for you, my beloved parents, for you’re so kind, you live so little for yourselves and far too much for us.”3 He explained his choice of Paris with the sort of verbiage of which he became the master: “Whereupon I returned to my bourgeois common sense and once again burned what I had adored; i.e., when one is young one speaks for the sake of speaking, and goes on doing just that, actually, more or less until one dies. (Those who say nothing are the smarties, of course; and I’ve noticed I always had a chattering temperament.) The received opinion is this: that I lack any solid basis, that I don’t know my trade, which is exactly what I must now learn.” The solution was a job in France: “My tastes are Latin tastes…. In Paris (nor does one have to be somewhat cracked to believe it)…they build just as big and with just as modern methods as they do in Germany.”

“One thing you can be at peace about,” he assured his parents, “I’m anything but a ‘vain boaster,’ and I need to muster all my courage in order to face up to the future as it looks to me. I’m too much of a worker, and I make myself stupid because of it. No question about it, I must let the young man in me speak, otherwise I’ll shrivel away to nothing, and I spend my evenings making projects solely in order to do nothing or to kid around…. My trade or my vocation is uniquely or rather must be in art, a young man of my age must keep his artistic fibers vibrating on all occasions. One must have a daily bread in art, an atmosphere of art. Here in Vienna, if it weren’t for music, one would have to do away with oneself.”4 In Paris, on the other hand, he would see Notre-Dame, the Louvre, and other great sights he knew only from photographs.

“Before me stretches the vast battlefield of Art, which devours so many men’s lives but which I must embark upon, and right away. That is why I am going to Paris.” His parents had to understand that he had endured all he could; he begged for their support. “I need your confidence. Above all, my dear good parents, stop saying I make you bitter. Whom else can I love except you?…Trust me, I love you, and you know quite well that all I have is you. I embrace you both, and thank you eternally all over again.”5

To reconcile his need for his parents’ approval with his indomitable will to go his own way was his most urgent task.

2

When Charles-Edouard Jeanneret arrived in Paris, he had all the expectations of a provincial. The disappointment stung.

His train reached the French capital after nightfall. Throughout the long journey, he had been picturing his life in the city of light. When he walked out of the Gare de l’Est on that March evening in 1908, little was as he had imagined. Rain was bucketing down. As he wandered into the aftermath of the celebration of Lent Tuesday, the masks and confetti in the mud struck him as sinister.

He had in his pocket the address of a hotel where one of his classmates from art school was staying. It was on the rue Charlot, a narrow street populated mainly by wholesalers and small businesses, not far from the sprawling place de la République. Finding his way on foot, Jeanneret encountered none of the monuments, bridges, or parks that composed his image of Paris. Even at night, the rue Charlot was commercial and noisy. The hotel itself was a disgusting hovel. As it would be told in the biography he masterminded a quarter of a century later, “His first contact with Paris—the Paris of fiacres, buses, double-decker trams—far from affording him the anticipated amazement, filled him with sadness and caused him something very like anguish.”6

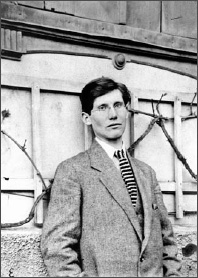

In Paris, ca. 1908

Two letters awaited him at the front desk. One, from L’Eplattenier, chastised him for this rash move. His former master and guide warned him that Paris had become a hotbed of artistic decadence. The other, from his father, alerted Edouard that he would receive no support in this “modern Babylon.”7

At least that is how Le Corbusier spun the tale via Gauthier—in whose book he arrived in Paris a month earlier than was the case. The reprimands had actually reached him when he was still in Vienna. But it makes a better story this way. The image of the solitary survivor, braving opposition with only a few sous in his pocket, was embellished by making those hostile letters part of his greeting to his new life. Similarly, Le Corbusier removed Perrin from the picture, although his old friend was with him; it’s a more dramatic tale if Charles-Edouard Jeanneret was entirely alone.

3

What Le Corbusier later presented as a struggle against all odds, with a prolonged stay in the hovel, actually took an upward turn the day following his arrival. In his contemporaneous letters to L’Eplattenier, his spirits lifted as soon as he saw Notre-Dame and the Eiffel Tower. Almost immediately, he took a pleasant room in a small hotel on the rue des Ecoles, in a charming neighborhood on the Left Bank.

The architecture of this area, on one of Paris’s highest hills, was on the same scale as in La Chaux-de-Fonds. But while the Swiss city was a rigid grid of rows of unvaried five-story structures, this corner of Paris consisted of ancient townhouses abutting more recent Art Nouveau facades on angled byways that together resembled a spider’s web. A vitality and playfulness replaced the dour elevations of Jeanneret’s hometown. Now he was surrounded by both grandeur and intimacy—from the massive Ecole Polytechnique, completed in the aftermath of the French revolution, and the imposing Pantheon, to picturesque squares and narrow streets with a proliferation of food shops and fine bakeries. From the solitary window of his attic room, he could “contemplate at the same time the gilding of the Sainte-Chapelle and the whiteness of Sacré-Coeur.”8 All of Paris, from Vincennes to the Arc de Triomphe, opened before his eye.

On one of his long daily walks, Jeanneret accidentally found himself at the Salon des Indépendants. A large canvas by Henri Matisse made him stagger backward in consternation over “enormous women with skin that looked boiled.”9 The young Swiss who in those days was painting small-scale, tame watercolors could not fathom Matisse’s distortions of form and color.

When he audited a course at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, however, he loathed the academic style it promulgated. What mesmerized young Jeanneret, rather, were the qualities of freedom and inventiveness he discovered in the glasswork of Lalique, the sculpture of Rodin, and the buildings of Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard, for whom his companion Perrin went to work. Unlike Vienna, Paris had artistic practitioners with taste and imagination.

4

Jeanneret soon began to bang on the office doors of Paris’s best-known architects. Frantz Jourdain, architect of the Samaritaine department store and founder and president of the Salon d’Automne, liked the drawings the audacious young Swiss had made in Italy. Jourdain paved the way for him to meet others in the Salon hierarchy, who asked him to work on a polychrome decorative frieze for a cornice. Jeanneret deemed the task beneath him and went instead to see Eugène Grasset, whose book on ornament had obsessed him in art school. Armed with his new Parisian cartes de visite, he talked his way into Grasset’s office and got the master to look at the same drawings that had won over Jourdain. Grasset’s response was to rail against the current Parisian architecture scene: “complete decadence, inveterate academicism, the low bourgeois utilitarianism of the rental-warren.” Jeanneret asked the oracle if there was any hope whatsoever, which prompted Grasset to make a pronouncement that changed his young listener’s life: “Everything can be saved by a method of construction which is beginning to be widespread: you make board boxes, you put iron rods inside and fill them up with concrete…. The result: pure forms of coffering. It’s called reinforced concrete. So go and see the Perret brothers.”10

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret followed the advice without a moment’s hesitation.

AUGUSTE PERRET was forty-four years old, Gustave forty-one. The sons of a Belgian building contractor, they had developed a speciality in reinforced concrete and were engaged in unprecedented feats of construction. Four years prior to the arrival of Jeanneret at their door, they had completed a bold reinforced-concrete apartment building in the sixteenth arrondissement on the rue Franklin, near the Trocadéro, which served to demonstrate the technology and their quality of workmanship.

Coming up from the Seine, looking across the rue Franklin, Jeanneret faced a lithe yet massive seven-story structure visibly standing on tall, narrow concrete legs. The lively facade presented the structural skeleton unclad, as one would normally find it only in buildings still under construction. The candor was unprecedented.

Instead of flowing smoothly along the line of the street like its neighbors on either side, the front of 25 bis was a sequence of deeply cut recesses, bold iron railings, and large-paned windows. Because the narrow site did not permit an interior courtyard, an equivalent courtyard—sliced by the line of the sidewalk—was moved to the front. In this three-quarters court, the upbeat apartment house embraces the daylight.

On its slope facing the Eiffel Tower, the building was—as it still is—more energetic and animated, as well as taller and whiter, than its nineteenth-century neighbors. A panoply of decorative coverings made it the machine-cut descendant of Jeanneret’s beloved cathedral facade in Siena.

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret absorbed all of this as he walked into the Perret brothers’ offices on the ground floor. He was stunned even further by the absence of internal structural columns—possible because the entire building was supported on external concrete posts. The effect was liberating.

Again, the young man presented his Italian drawings as his entry ticket to the office of an important architect. Auguste Perret took one look at the sheets of Italian scenes and announced, “You will be my right hand.”11

The four months of searching had paid off. In his new workplace, the cocky young Swiss was at home as never before. The Perrets’ courage to buck the artistic tide, their intelligence and honesty, and their technical sophistication were unlike anything he had encountered in so-called modern Vienna.

Auguste and Gustave Perret believed that the design and appearance of a building should honor its function and program. It was also vital to build with accessible materials and to utilize current technology. Jeanneret thrilled to their startling insistence that building design cease inserting antiquated forms and obscure substances into our lives. They offered the voice of truth.

5

For fourteen months, Jeanneret worked five hours every afternoon for the Perret brothers, doing drafting and preparing blueprints. He earned six francs per day, which enabled him to move into nicer digs, another single room tucked under a mansard roof, but now at 3 quai Saint-Michel, overlooking the Seine. When he wasn’t working, he went to museums and sketched. He focused mainly on vernacular art: Greek and Etruscan pottery, Egyptian and Persian painting, medieval tapestries and statuary, and Chinese and Hindu bronzes. In the dusty and obscure rooms of the Musée d’Ethnographie at the Trocadéro—a place to which he often repaired with great pleasure, relishing the solitude—he succumbed to the enchantment of Peruvian pottery, Aztec sculpture, and African textiles and wood carvings.

Jeanneret took it upon himself to go to the Ministry of Beaux-Arts, the administrative office for Paris’s monuments. There he managed to obtain a bunch of keys that opened locked gates and doors within the great Gothic cathedral of Notre-Dame. He had often studied its exterior from his apartment window; now he explored the tops of the steeples and climbed the pinnacles and buttresses. The structure and construction thrilled him, but the decorated surfaces were an irritant. “The plans and the Gothic cross-section are magnificent, full of ingenuity, but their verification cannot be achieved by what meets the eye. An engineer’s triumph, a plastic defeat.”12

He continued to write regularly to his mentor L’Eplattenier, but the more colorful, worldly Auguste Perret was becoming his new role model. “Auguste Perret has a nabob’s tastes,” he wrote. “He would like to sit enthroned while grinning in secret; he loves things preciously made, a Japanese netsuke, a piece of woven Moroccan leather, a shapely sword, delicate cookery…he’s sublime with clients. He holds his head high…chooses his neckties very carefully…. His worktable is always impeccably arranged…. He’d have liked to be the shah of Persia, but he’d have decapitated his enemies with a wooden sword and offered his victims cigarettes after a session of torture. He liked to consider himself a revolutionary figure, and in fact he carried out his revolution meticulously, with deep love, respectful and assiduous in his vocation, which is to build. And to build meticulously with reinforced concrete, in this period of utter decadence.”13

Meanwhile, Don Quixote and writings by Nietzsche, both of which he read continually, corresponded to his own experience of the world. In July, he wrote L’Eplattenier, “Life, at this particular period of my existence, is a grueling combat. If every day I see new difficulties cropping up, if I find they are more numerous than those which my colleagues working toward the same goal must overcome, it is because I feel I’m an ‘outlaw.’”14

As if he were his own advisor and pupil at the same time, the young man laid out his goals to his old teacher: “I’m attempting to establish a rational program for myself, one which will gradually allow me to learn the tricks of the trade. Every day I do my work, and I frequently catch myself getting excited over a difficult, mysterious problem, enthusiastic when I’ve found the solution. For the rest, aside from the abstraction of pure mathematics, I read Viollet-le-Duc, a man so wise, so logical, so clear, and so exact in his observations. I have Viollet-le-Duc and I have Notre-Dame, which serves as my laboratory, so to speak.”15

After conjuring for his parents the nineteenth-century French architect who had led the Gothic revival and restored Notre-Dame, Jeanneret put himself down: “I feel deeply disgusted with myself. No, honestly, I am horrified every day by discovering my inability to hold a pencil; I don’t feel the form, I can’t make a form revolve: it drives me to despair.” The self-denigration sparked an intense drive to do better. “I try to control myself these days, to wrench myself out of this disgust: I seek geometrically the principle of the model, the decomposition of light and shadow on a sphere, an oval, a vase or some other object.”16 That rapport with light effects was to be Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s salvation and a fundament of Le Corbusier’s genius.

6

At the start of July 1908, Jeanneret wrote L’Eplattenier, “What constitutes the great disaster, or perhaps the great success—disaster because synonymous with struggle, success because it is a thirst for ideals, for aspiration—is that the critical faculty grows sharper, becomes imperious, decisive, commanding. It turns you into a painter, an incompetent, a fraud; it says to me: ‘You’re nothing but an imbecile, and I never would have thought such a thing of you. I had illusions about you, fantasies, I saw you heading for triumph, swimming through clouds of glory.’…How severe the critic becomes, a fellow who doesn’t mince words…. But God has made us in His image and He remains the great face, the great passion to make the Good and the Beautiful, and at times that power prevails over all else, which is why at this very moment I am not a clerk in an office or a grocery clerk!”17

Aspiring toward the “beautiful” and trying to cope with his meandering mind, he tried to pare down his life to the rigor and bare simplicity of a tent in a battlefield. Jeanneret embraced a leaner, purer, tougher existence. “I am sometimes invited into bourgeois homes, which awakens tremendous exasperations,” he wrote L’Eplattenier.18 Middle-class life was a trap, dominated by heathens who mocked Rodin and did not understand Wagner. Superfluous comforts and material well-being were deadening. Even Jeanneret’s fellow students drove him to despair with their false values and lack of idealism. “Oh, how eagerly I wish that my friends, our comrades, would discard that mediocre life with its everyday satisfactions and abandon what they hold most dear, supposing as they do that such things are good—if only they realized how petty their aims are, and how little they’re thinking,” he wrote.19

Alone on the quai Saint-Michel, Jeanneret relished his “fruitful hours of solitude, hours during which one undermines, when the lash bites into the flesh.—Oh, if only I had a little more time to think, to learn! Real life, paltry as it is, gobbles the hours.”20 He was to refer to the flagellating whip for the rest of his life.

In his hermetic existence, the sole encounters he valued were with Grasset and other elderly men who had devoted their lives to art: “Such men’s hair has turned white; yet it is they who are keepers of the true devouring flame. Such men have the already idealized, already paradisiac faith of those initiates who have seen and know the truth. One leaves their presence scourged but with a high heart.”21

Jeanneret counted on L’Eplattenier to understand all this. He wrote his master, “It is by thought that today or tomorrow the new art will be made. Thought withdraws and requires combat. And to encounter thought in order to give battle, one must proceed into solitude. Paris affords solitude to those who ardently seek silence, the aridity of retreat.” If he acted properly, this magical metropolis was a place to be productive: “Time in Paris is fruitful for those who seek, from the passing hours, a harvest of strength. Paris the great city—of thoughts—in which one is lost unless one is severe and pitiless to oneself.”22 It was a religious quest, worth the requisite sacrifices because it replaced his anguish of Vienna with values and purpose.

“Vienna having given the death blow to my purely plastic conceptions of architecture (no more than the search for forms), and having arrived in Paris, I felt an enormous void and said to myself: wretch! you still know nothing at all, and alas you don’t even know you know nothing.” His self-prescribed program in the French capital had succeeded: “I suspected from the study of the Romanesque that architecture was not a matter of the eurythmia of forms.” His instruction in “mechanics” and “statics” had added to his growth: “It’s arduous, this mathematics, but beautiful—so logical, so perfect!”23

Now that he had recovered from Switzerland and Austria, his ascendancy was under way.

7

Paris had effected his metamorphosis. “These eight months in Paris shout: logic, truth, honesty, behind the dream of the arts of the past. Eyes open, forward! Word for word, with all the value words can have, Paris tells me: Burn what you have loved and worship what you were burning,” he wrote to L’Eplattenier. This outburst was also a diatribe: “You, Grasset, Sauvage–Jourdain, Paquet, and the rest, you are liars—Grasset, that model of truth, a liar, because you don’t know what architecture is—but the rest of you, architects all, liars all, yes, and cowards as well.” He was enraged that none of his former mentors had led him toward the realization that “the architect must be a man with a logical brain…a man of knowledge as well as of heart, artist and scientist.”24

Jeanneret charted his course accordingly. A new art would be born in Paris, and he would be part of the breakthrough. His excitement took him over the edge of logical thinking: “As a tree on a crag which has taken twenty years to anchor its roots and which generously concludes: ‘I have struggled—my offspring will gain by it!’ and lets its seeds fall on the few patches of soil mottling the crag, soil which the tree itself has formed with its dead leaves—with its pain; the crag warms in the sun, the seeds flourish, and the rootlets grow—with what vigor! what joy! to stretch the tiny leaves to the sky…. But the sun heats the crag; the plant in anguish feels the stupor of excessive heat; it tries to send its rootlets into the shade of its great protector. Yet the tree has taken twenty years to anchor its roots, and with what a struggle—its limbs filling the crannies of the rock. In anguish, the seedling reproaches the tree that has created it. The seedling curses the tree and dies. It dies of not having lived—by itself…. That is what I see in this country. Hence my anguish. I say: create for twenty years and dare to continue creating still: aberration, error, prodigious blindness—unheard-of pride. Trying to sing when you do not yet have lungs! In what ignorance of your very being must you be plunged?…The parable of the tree inspires me with fear…fear for the tree that prepares itself for suffering. For you are a being so full of love that your heart will be plunged into mourning to see the incandescent life—the life that must be gained in order to struggle against it—coming like a cyclone to burn the little plants which so proudly, so joyously aimed their leaves at the sky.”25

He announced to L’Eplattenier, “My struggle against you, my beloved master, will be against this error.” His “struggle against friends” was “the struggle against their ignorance…. They do not know what Art is.” He, on the other hand, recognized his pathetic state: “I know I know nothing.” As he beat the evil out of himself, Jeanneret swooned over the new truth he at last glimpsed: “Vienna gave me too strong a shock. At present I am a man without resources, incapable of creating or of executing anything. I no longer see in works of art, or in nature when I go for a walk, anything but life, the mad sinuous curves and spirals, the shoots opening into magical palmettos. I say ‘seeing them’ it would be more correct to say that I foresee them. But the shock of Vienna was so powerful, the disgust so deep, that I am no longer attached to execution; only fragments of art delight me. And so I do not know one iota of my trade.”26

8

Jeanneret read Ernest Renan’s Life of Jesus.27 He marked the most hypnotic passages and wrote their page numbers on the title page.28 Language he was to use for the rest of his life came from Renan’s phraseology.

Jeanneret drew excited lines next to “Jesus is not a spiritualist; for him everything has a palpable realization. But he is a fulfilled idealist, for him matter is only the sign of the idea.” In the margins, the young architect scribbled: “And I herewith create everything anew! This is the feature all reformers share.” He marked with a double line the statement that Jesus “had renounced politics; the example of Judas the Gaulonite had shown him the futility of popular sedition.” Renan’s Jesus was his model, or at least his excuse, when he later worked with any regime that would allow him to build. By declaring politics insignificant, he revealed to the world this truth: “that the nation is not everything.”29

The other text he double marked was the single sentence “For him, freedom is truth.” And he pressed his pencil so hard that he dented the margin next to Renan’s conclusion: “Inevitably a moral and virtuous humanity will have its revenge, and one day the sentiment of the honest man, the poor man, will judge the world, and on that day the ideal figure of Jesus will be the confusion of the frivolous who have not believed in virtue, the selfish who have been unable to achieve it…. A sort of magnificent divination seems to have guided the incomparable master here, and to have sustained him in a generalized sublimity embracing many kinds of truths at once.”30 The man who would make himself another “LC” was to rail forever at those frivolous and selfish creatures who could not recognize a savior in their midst.

9

On May 12, 1908, Georges-Edouard and Marie Charlotte Amélie Jeanneret celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. Georges wrote in his diary, “Thanks be to God this quarter of a century of life together has brought us more intimate days than pains, aside from everyday cares; we have acquired a modest comfort, at least our daily bread is secured for the morrow; our two sons have caused us no moral torments, their behavior has been excellent, their moral nature is intact: their careers are not yet certain, yet they pursue them with great and cheerful energy. My wife has been a discreet helpmate who never flinched from duty. Our health, aside from a few minor cares, has remained good. The four of us live in harmony, closely linked by affection.”31

Georges could overlook his rage at Edouard’s trip to Italy and subsequent move to Paris now that the younger son had a job. That was more than could be said for Albert, who, after earning his “diploma of virtuosity” from the music conservatory in Geneva, went off into the mountains alone. Albert declared himself utterly confused, unable to do much of anything. Although he then returned to Geneva to teach and performed publicly in La Chaux-de-Fonds, in March 1909 Albert said that he had to stop playing the violin for at least a year, as he was suffering from pains in his arms. Making matters worse, a lull in Georges’s work meant that Marie’s piano teaching was their main source of support.

At the end of 1908, when Edouard had finally returned home after an absence of a year and a half, he had begun to assume the role of the easier child. Georges reported in his diary in January, “Though he still dresses rather deplorably, we found him to be a good talker, of solid morals and firm opinions (despite the complete modification of his beliefs and his faith); tall, with a new reddish-blond beard; still confident in the future, energetic, and in good health!”32

IN MID-MAY OF 1909, Georges and Marie Jeanneret visited Edouard in Paris—the first time they had ventured so far from La Chaux-de-Fonds. Georges felt that the eight francs a night they paid for their twin-bedded room at the Hotel du Quai Voltaire, convenient to Edouard’s apartment and the Louvre, was warranted. This was high living for the Jeannerets, but although the total they dispensed for the trip depleted the accumulated interest in their savings account, it did not touch the capital. The watchcase decorator and piano teacher took great pleasure in the sights Edouard had chosen for them to see, including a performance by Sarah Bernhardt. Georges made another happy diary entry: “Our son knows his town like a native and was of great assistance to us, and of great interest through his knowledge of art, his sure judgment, his amiability, his good manners, despite his unfortunate clothes.”33

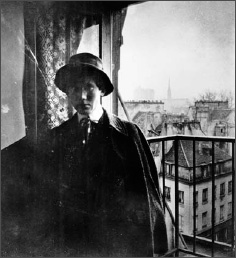

Dressed as a “rapin” in his garret at 9 rue des Ecoles, Paris (1908–1909). The rapin coat was the unofficial uniform for students in Beaux-Arts courses.

In September, however, in one of his most bizarre missives to date, Edouard suggested to his parents that good clothing was not his only lack. “To make love, le bel amour, takes cash, fine clothes, and the gift of yourself, and for lack of cash, fine clothes, and the capacity to give myself, such a thing is quite impossible for me, since as I’ve told you I belong for the time being to Mistress Escapade, and of course all substitutes find me retrograde, inferior, and, on the other hand, sometimes quite severe!…One lives a life contra naturam, that’s obvious, and in spite of all that might be said, one needs woman, that subtle element consisting of everything we lack, but without which we are incomplete.”34

THE JEANNERET SONS both seemed determined to jolt their parents.

Albert, who spent a few weeks in Edouard’s room with him, reported deliriously about their drinking multiple liters of white wine one evening and cavorting in the countryside on a Sunday when the temperature reached forty degrees: “We terrified a young virgin (approximately 40–50 years old) who had ventured to accompany us, but who quickly changed direction at the sight of our extremely light garments. Unfortunately (and this will be imputed to us by daylight) we introduced certain germs into the hearts of other passers-by.” The Jeanneret boys ended up spending the night outside, sleeping on their backs with their feet practically in the Seine; “we tasted the delights of letting ourselves live.” Edouard told his mother and father, “We must find a way to walk the streets stark naked,” but added, “I find I have a character likely to overload itself with work and insufficiently disposed to enjoy life.” When he wrote that he was “stupidly delighted” in the garden of the Palais Royal with Albert, it was “not for the sake of a good time, but because it was a mistake to work with an exhausted mind.”35

With Albert behind him at 3 quai Saint-Michel, 1908

THEN, ON NOVEMBER 9, 1909, Edouard terminated his connection with the Perrets. Postponing his return until his money ran out, he wrote his parents, “In my hours of freedom, I feel the rebirth of an artistic fiber, and I rejoice in this vacation during which I can surrender a little to poetry.”36 At the end of the first week of December, Jeanneret returned to La Chaux-de-Fonds. His plan was to spend three months in a rented farmhouse. Although he had initially rejected L’Eplattenier’s counsel that he work in Germany, now he wrote his master that he had decided to go to Munich and then Berlin. Yet again, everything had changed except for his burning goal: to understand architecture.

Self-portrait drawing as the “Grand Condor,” on a postcard to his parents, Christmas 1909