XII

1

The milestone of Jeanneret’s thirtieth birthday was looming (see color plate 1). When he was invited to Frankfurt to work on some municipal building projects, he accepted. But at the passport office in Neuchâtel, as he stood at the wooden counter awaiting the visa stamp, he changed his mind.

Having walked into that office to gain the right to move to Germany, he requested a passport for an unlimited time period in France. The change of heart took him by surprise, but knowing that he could count on Max Du Bois to help set him up in Paris, he had no doubt. Du Bois had forgiven Jeanneret for his treatment of him on the Dom-ino project, and repeatedly insisted that he was destined to perish if he did not leave their stultifying natal city and move to Paris permanently. Du Bois had founded the Société d’Application du Béton Armé (SABA) to promote the use of reinforced concrete, and he wanted Jeanneret to join him in making this durable and efficient new material available through mass production.

All that was left for Jeanneret to do was raise some funds and pack up. After returning to La Chaux-de-Fonds, he arranged a bank loan, which was granted because of fees he was still owed for the movie theatre. He also found three local businessmen who gave him a small amount of capital to invest on their behalf in new enterprises associated with the construction business. With twenty thousand francs—roughly the equivalent of thirty thousand dollars today—and a couple of suitcases, he again took the train to Paris. For the rest of his life, the French capital served as his home and the campaign headquarters for his battle to change all human habitation.

2

The Paris Jeanneret encountered when he arrived on February 9, 1917, had been torn asunder by aerial bombardment. Many people were at the brink of, starvation, and everyone felt constant danger. But to the young man from the Alps, the French metropolis was “the crucible, the diapason, and the torch.”1 He knew it had been the source for Géricault, Degas, Ingres, Manet, Courbet, Monet, Seurat, and Matisse. He was determined to join their ranks.

Jeanneret stayed in Max Du Bois’s fifth-floor walk-up apartment. In his later reconstruction of his personal history, Le Corbusier presented himself as the intrepid country boy who went to the big city to make his way aided by nobody and who launched himself in solitude. He would have people think that, entirely on his own, he found a place to live, began an architecture practice, became a businessman, and located clients. He obfuscated the central role of Du Bois—who not only put a roof over his head and gave him a job with SABA but also introduced him to wealthy Swiss and members of the French business community.

While in Du Bois’s flat, Jeanneret set up a small office in a former kitchen and maid’s room on the seventh floor of a charmless apartment building on the rue de Belzunce, near the Gare du Nord. It was a “dirty hole,” but the rent was cheap, and within five days he stripped the rough hovel into a fresh, clean space.2 “I have ‘boned’ my workplace with complete success,” he wrote his parents, jubilant at having cleansed it of its layers of excess and cut through to the structure. In these rudimentary headquarters, he began work as a consultant for SABA.

Next, Jeanneret found his own place to live. This apartment, which he was to inhabit for seventeen years, was, like his office, high up in former servants’ quarters. But the building—at 20 rue Jacob—had far more charm. The narrow and quiet rue Jacob was one of the most lovely streets of St. Germain-des-Prés, near the Seine, in a neighborhood populated by artists and writers and full of small bistros and inviting cafés. Number twenty, a distinguished seventeenth-century residence built around a cobblestone courtyard with fragrant linden trees, was the former town house of Adrienne Lecouvreur (whose name may have subtly been one of the many factors contributing to the one Jeanneret soon chose for himself). To reach his small space there, he ascended an oval spiral staircase constructed in dark wood. Under the mansard roof, surrounded by plaster that dated back to the reign of Louis XIV, he in time dreamed up his streamlined modernism.

He was enthralled to be in a space that had been inhabited by the colorful Lecouvreur, an immensely popular actress early in the eighteenth century. Her romance with Maurice de Saxe, a distinguished nobleman in the court of Louis XIV, was the subject of a poem by her friend Voltaire, as well as of an opera and a play. It ended tragically—Lecouvreur was apparently poisoned, at age thirty-seven, by her rival in de Saxe’s life, the duchess of Bouillon, and the Catholic Church denied her a Christian burial—but Jeanneret often referred to the golden time when de Saxe constructed a small temple that still stood in the garden. Jeanneret sketched it for Ritter and wrote him, “I’m thrilled to be able to paint the roof tiles of Maurice de Saxe. Shall I manage to live worthily in this residence?”3

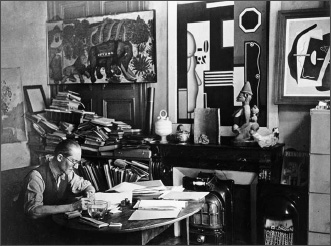

At 20 rue Jacob, late 1920s. Photo by Brassaï

The reality of Jeanneret’s own life was less ideal. The rooms at 20 rue Jacob were sometimes bitterly cold, and no heating fuel was available. He had scarcely enough food. But, through the tricks of art, he transformed the garret. To warm up the flat, he painted on one wall a landscape of a tropical scene with palm trees bathed by sunlight.4 Visual illusion provided salvation and joy.

3

Jeanneret became absorbed by the prostitutes he studied and coveted in the Métro. He was a connoisseur of them, even though he considered the women mostly unobtainable. For Ritter and Czadra, Jeanneret sketched the profile of one who had bold features like a Greek warrior’s, her hat and coiffure an exotic blend of pouf and ornament that he rendered in elaborate detail. He wrote, “Yesterday in the tram at La Roquette I saw two whores from the brothels out there, one of whom was a marvel; I’m eliminating the first page of this letter, or rather I’m completing it by this notation: the Lord has created a lovely animal.”5

But sex was often a struggle for him: “The act of love is rather complicated to perform; it requires special circumstances. I no longer manage to have my old magnificent erections, and I fall back—in a fatally Oriental impulse—on visions of Spanish fly.”6 Jeanneret said “fatally” because he knew that, while a small amount of the famous aphrodisiac could help stimulate the blood flow as well as the kidneys, too much of the insect’s venom could kill someone.

A few weeks later, however, he saw, on the Métro, a prostitute with whom he had had sex. In one of his most obtuse soliloquies yet, he told Ritter that the encounter made him realize that he preferred the simpler women in cheap bordellos to the higher class of streetwalker whom he had drawn: “How I hate these cows! This is the second in months. I’m quite indifferent to all of them. What I lack is a sense of the ‘minaret.’ You know: the minaret rises solitary above the mosque, and pierces nothing but the sky. You tell me I need a Grand Passion. Thanks a lot. Except for the selfish pleasures of the heart, a woman is nothing but a bête d’apéritif. In which case I prefer the brothel, simply the animal and the water closet. I have close friends. O Adrienne [Lecouvreur], unless you manage to reincarnate yourself, your Maurice [de Saxe] will not be wearing out too many bedsprings under your alcove roof, well tiled though it be. In the calm of this garden and the solitude of this empty house, there’s room for the eloquent explanation of two storms; I don’t dissociate love from the tempest and from danger. Beyond a sinuous mouth and a pair of eyes, I require a chin and a forehead.”7

Jeanneret began writing a diary, which he sent in periodic installments to Ritter. In one entry, he confessed the problems of making love to these women: “But a man can’t give his body to these easy girls, for he feels something like fear. There’s no lust, only pity and affection, and instead of casting your seed into this public sewer, you’d like to caress these creatures, caress them gently. A lot they’d care for that!”8

At the end of January, Jeanneret went with Max Du Bois and his friend Marcel Rey to the Casino de Paris to see “Les dancing Girls” in The Flags of the Entente. An all-Negro orchestra played. Jeanneret was enraptured by their beauty and raw force. The women cavorting onstage impressed him much as the Pisa altarpiece and Balkan pottery had: “There was Gaby Deslys, whom I remember three days later as a pink vision of magnificent flesh, an image of primeval life. Idiot movements, whorehouse plastique, or more often just bourgeois asshole tricks. But flesh…but sap…Panting marble…Who cares how stupid she is, Gaby Deslys represents seduction for a sad and solitary heart like mine.”9

Yet for all his ardor, he remained more the observer than a participant. He wrote to Ritter, “There’s a lot of Woman around, as ever. How stupid all these men seem, who just because they’re sitting around a piece of meat think they’re becoming kindred spirits! But of course it’s for the sake of the nozzle this crowd gathers, each man wild to satisfy his brute need, his vital egoism. How stupid a man is in the last analysis! Yet what a piece of work is man.”10

In a diary entry a few weeks later, he linked a town center he loved with its beautiful women. “Pisa is surely one of the towns I love most. Life there seemed to flow slowly enough to let me enjoy the centuries as they pass. And Orcagna drew unforgettable women there.”11 From there he jumped to comments on Paul Poiret’s coiffures for music halls. Almost as much as he liked the Pisa cathedral, Jeanneret was fascinated by the ostrich feathers arranged like a peacock tail on Gaby Deslys’s head, which nearly doubled the height of her body. For months, he painted these women. But that was the extent of it: “What I need is to caress someone: my life is murderous,” Jeanneret reported in the diary he eventually sent to Ritter.12

Jeanneret was vaguer to his parents about the simultaneous attraction and repulsion he felt to prostitutes, but he wrote them as well about his struggles: “Yet this expression which I understand but which I fail to estimate properly, alas, for lack of having enjoyed that bittersweet fruit: the wild distress when there is passion in carnality, the thirst of one’s entire being, the indispensable presence, copenetration, reabsorption of every molecule.”13 The allure of “that bittersweet fruit” haunted him.

THE ACT OF LOVE and the making of buildings were inextricably linked in Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s mind. Going to brothels and realizing architecture required similar determination; the challenge was to get from the fantasy stage to efficacy. In his diary to Ritter, Jeanneret wrote, “I’m an architect, a builder. I like my drawing tables on their trestles, my telephone, my typewriter. I like the hiss of automobile tires and the clamor of the street. I’m not a castrato. I’ll pay my visits to that seething Montmartre sloping up toward Saint-Augustin. I won’t withdraw from life, I’ll do what everyone else does. And I’ll rent a big room, a workroom in which my furniture will shrink to nothing, and then the big walls will impose a grand design on me, in which my chaos will espouse the kinds of violence oriented toward a geometry as deliberately inscribed as the wheels and pulleys of a machine, and with the same lucidity, the same fantasy, the same concision.”14

Determined as he was to show his virility—to go to “that seething Montmartre” meant frequenting brothels—he couldn’t bring it off: “I complain: this is ridiculous. I had gone to the restaurant to pick up a girl. There are no girls left. My celibacy weighs on me.” On the Easter Monday when he recorded this, he was drinking cheap Chianti: “My life flows past, stupid, monotonous, tense, alone, unfortunately…. Now I’m at home drinking some kind of nasty alcoholic brew; I’ve turned on all my lamps. It’s cheerful here, this nest of mine—the former residence of a maid of Adrienne Lecouvreur. I’m alone, except for the mice doing their minuet on my ceiling.”

He envied an acquaintance who had “a mistress who is a real woman; he’s beyond me, I’m isolated, wounded, I suffer. I see the irony, the grotesquerie of life; I’d like to experience its beauty, its energy, along with this springtime, this joy, this living in spite of everything, this song of the sparrows, these skies of hope. My mind abandons itself to melancholy and assigned projects. How I long for the release of a natural, beneficent flowering.”

Jeanneret prized sexual potency as a mark of greatness. “To have or not to have…an erection. He who gets hard and stays with it is a man capable of strength, still a beast deserving to live in the sun.” Swiss men, he claimed, were eunuchs, but now he had left their neutered land behind: “I’m telling you this because it’s true. Since I get my erections normally, I believe in life, desire it, and this spring I even have the impression that the desired act is fulfilled and that I’m entering the CITY. I’m through with what’s back there…. I was a child of La Chaux-de-Fonds, brought up far from life and in fear (in the fear of God, they have effrontery to say)…. I’m entering the age of realization…. Now I’m a man nearly six feet tall named Jeanneret who’s an architect, who has no diploma, who’s capable of solving a problem and achieving his goal.”15

It was not to be as easy as he hoped.

4

At the end of April 1917, Jeanneret sent a postcard to Ritter from Chartres. It was of a single thirteenth-century figure from the North Portal, a solemn woman, looking downward, carved with great dignity, who represented “la Vie Contemplative.”16

On this card showing another tormented observer frozen into inaction, Jeanneret wrote, “Yes. Alas, one must look ahead and fulfill one’s destiny. This cathedral is as much the house of the Devil as of God. The tragic heroism of these stones deserves a portico of hell; here, in a titanic effort, man expresses his own damnation. No one could imagine Chartres from looking at other cathedrals: the foundations are like the successive movements of a symphony and of fatally incomplete thunders: there is moonlight in these stones, and an unheard uproar.”17

World events were making his incertitude worse. In February, the Bolsheviks had overthrown the monarchy in Russia. On April 6, the United States had entered the war in Europe. No place seemed stable, even if the epidemic of mutiny in France had been ended when Henri Pétain, the new commander in chief and future Maréchal, and Georges Clemenceau, the new premier, restored order.

Yet three days after sending that postcard from Chartres, Jeanneret was so enthusiastic about the richness of human history and the bounty of nature that he was displaying symptoms of what today is called “rapid cycling.” He wrote Ritter and Czadra a single, rambling, manic sentence:

Dear friends. It’s the fault of too many buds bursting into bloom outside the open windows, of too many branches shaken by a warm wind—old branches, as old as Maurice de Saxe, above the flowerbeds entirely covered with ivy; of too many irresistible appeals from the old bridges of Androuet du Cerceau, with their cornices of flags and banners, their opulence of royal pomp; of too many quais between which flows a river as joyous as silk—quais where once again the great trees spread their limbs wide in a touching blue sky; of that overpowering murmur I hear from my desk, coming from far away—I hear it coming from the other side of my wall, coming from distant walls to strange crenellations against a sky that is pink at this time of day—that murmur in which I can make out an occasional raucous call of the bargemen on the river, under the bridges; of too many sweet, sad impressions which drown me quite “dolorously” because it is really too beautiful and because a man cannot be happy with a tangible and present happiness, and because there pass through the air shudders of unknown and troubling future things, inevitably sad since I feel I cannot measure my happiness, that I lack an inner vitality strong enough to silence those far-off enthusiastic branches: all too often the calm of my walls yields to the raucous call of the passing Unknown, and as I follow the flood of a destiny to which I attribute so many surprises, I proceed beyond my crenellations one after the next, toward the boundaries of nations, and toward places where there are people I think of and whom I can beguile with such spleens as these. That is why I have waited so long to write.

Man is very much alone.18

The frenzy of enthusiasm required an outlet if he was to overcome that solitude. He continued: “I feel that I cannot discern my happiness, that I lack a soul generous enough to deck my heart with flags.” Sooner than he imagined, however, he was to channel his ecstasy into architecture.

5

On the evening of May 17, 1917, Jeanneret went to a performance of the Ballets Russes at the Théâtre du Châtelet that, in retrospect, stood out as a milestone of modern cultural history. When the dancers from Moscow, impeccably trained in the imperial tradition, soared above the Parisian stage to the strains of music as advanced as the latest progress in air travel, the possibilities of human motion took a new dimension.

That night, an art form that had been the precinct of the elite embraced mass culture. This revolution, a triumph of modernism, thrilled the onlooker from La Chaux-de-Fonds. That it was loudly booed and brought on the rage and opprobrium of the sleepy, reactionary bourgeoisie enhanced rather than diminished his pleasure.

The ballet, called Parade, reflected a radical preference for settings like fairgrounds and the circus tent. It moved as far afield from the refinement of the Bolshoi and its ballerinas enacting fairy tales in tutus as Jeanneret had when he shifted his sights from the splendors of Versailles to humble dwellings in Balkan villages. The new ballet had been the idea of Jean Cocteau. In 1915, Cocteau and the composer Erik Satie created Parade for the dynamic Russian choreographer Sergey Diaghilev. Pablo Picasso designed the sets and costumes.

Parade threw off the shackles of elegance and embraced the tawdry atmosphere of the music hall. Three characters, ten feet tall, became moving skyscrapers; one turned into a tree alongside a boulevard while another was a horse. Two acrobats flew into the air, and a Chinese conjuror removed an egg from his pigtail, ate it, and then discovered it on the toe of his shoe. An American girl rode a bicycle, danced a ragtime, imitated Charlie Chaplin, snapped photos, boxed, and went after an imaginary thief with a revolver.

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret was fired up. But most of the audience was incensed. When the performance ended, several threatened the producer physically. Many shouted “Filthy Boches”—a swipe at Germans uttered often during the war. As tempers flared, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire took the stage. Recently wounded in battle, he had a bandage wrapped around his forehead. He was dressed in his military uniform and wore his Croix de Guerre. The irate crowd had no choice but to accord him the respect warranted by a hero and calmed down. Apollinaire urged them to be more tolerant.

For the program that evening, this proponent of modernism had written an essay entitled “Parade ou l’esprit nouveau.” Apollinaire animatedly defined that “esprit nouveau” as the means by which art was successfully combined with the most recent progress made by science and industry. In its brazen simplicity, “l’esprit nouveau” became Jeanneret’s gospel. He enthusiastically scribbled notes in the program and sketched some of the sets. The élan of Parade and the boldness of Apollinaire’s text signified the future.

6

At the beginning of July, Jeanneret told Ritter, in scintillating detail, “the epilogue to ‘the night at Aristide Maillol’s’: Today Aristide Maillol told me: ‘I kicked Gastonibus out, because the worst of it, after living four years in my house, was that Gastonibus, instead of vanishing somewhere into the crowds of Paris, came to rest in my own niece’s house, a house that belongs to me.” Jeanneret reiterated the horror of the lovers using Maillol’s own bed, instructing, “Reread for memory’s sake in what bed this all took place that night, already two years ago! Keep the gossip between ourselves, Gastonibus being the present and future glory of the chamberpot city under the mountains.”19

The place like a toilet was La Chaux-de-Fonds, and Gastonibus Beguinus was merely the first new persona Charles-Edouard Jeanneret would assume in order to have the virility he craved.

7

In May, Jeanneret founded the Société d’Entreprises Industrielles et d’Etudes, leasing a new office at 29 bis rue d’Astorg—a location near the Madeleine that put him at the center of bustling, commercial Paris. In his free time, he dedicated himself to watercolors (see color plate 2).

Beyond that, on October 16, ten days after his thirtieth birthday, he opened an enterprise to manufacture reinforced-concrete bricks. Max Du Bois had provided the financial backing for him to rent space in the St. Lumière power station in Alfortville, on the Seine on the outskirts of Paris. The blocks were made of by-products from the station and could easily be shipped from the location on the river. Jeanneret designed himself a coat of arms bearing the statement “The world is without pity,” but he was ebullient as he launched the commercial venture with which he planned to earn his fortune while also practicing architecture and painting.

Jeanneret entered one of his periods of ecstasy. Moneymaking and the betterment of the world could go hand in hand. With his start as a businessman, he resumed the diary he sent to Ritter: “Alfortville is begun! We’re going to make bricks. The factory, the site actually, is attractive, the machines powerful, the situation magnificent. Enormous gasometers, the four overwhelming Est-Lumière chimneys right next to our property.” The fast pulse of industry was pure poetry: “Coming home at nightfall, I saw the water shimmering and the great factories smoking, their luminous bays reflected in the river.”20

Still, Jeanneret deprecated the old-fashioned style and suburban ambience of the Napoleon the First building where his business was housed. And he disdained himself for his new alliance with the lowest of all human forms: the bourgeoisie: “I breathed deeply over my property: the bureaucrat, the trustee, the businessman, the eunuch architect will vanish someday—eventually! I’ll make fine engravings of my factory, and I’ll be able to speak of ‘my stocks’ and of ‘my sales’ like any wine merchant.”21

His mental swings were rapid and extreme. Suddenly, the self-loathing entrepreneur, after thinking of great architecture rather than business, was riding high again: “Tonight I leafed through my files from the Bibliothèque Nationale (more than five hundred sketches of cities). The whole world in extracts from old engravings. What flavor! Amplitude and imagination above all; overflowing. I am jubilant. And delicious inscriptions, ‘sweet smelling roses’ of Jacques Callot. And the big cartouches of the Roman engravers. Those letters! If William Ritter were here, he’d rejoice for days. And I’d be hearing him. Rome inundates me, hypnotizes me. Good lord, what laughter! The scale and the poetry. And their consuls, and their old men. L’Eplattenier dared tell us they were corrupt; the wretch!”22

Then, as if a narcotic had worn off, he plummeted again. Only hours after committing his jubilance to paper, he lost confidence: “Sick all day. Solitude, entirely impregnated with Michelangelo. Still Rome! Tragic life, forced labor, implacable destiny. Tenderness, affection, the heart of that good, dolorous man. Fog outside. Silence here. My painting is still ten times less than what I wanted. I still don’t know how to set down a flat tone, nor how to shade a cube without 10 reflections, which do away with strength.”23

8

This time, Jeanneret remained glum until he immersed himself in architecture with such fervor that nothing could burst the bubble. When All Saints’ Day came six days later, he made his way through the rain to attend a morose mass at Notre-Dame and then chose to copy Rogier van der Weyden’s Déposition. It was a perfect recipe for gloom.

The copy was his fifth oil painting. Trying to master the medium, he transformed the Flemish master’s gripping scene of death and mourning, its dramatic gestures and anguished faces, into a freer rendition with his own modern coloring. The painting then fed a fantasy of his own death.

Jeanneret’s cold had evolved into a dreadful grippe—the sort of flu and sinus symptoms that would plague him regularly throughout his life. In the middle of the night after All Saints’ Day, he was hardly able to breathe. The problem intensified; suffering from the barklike gasping of croup, he had the agonizing sensation that he was suffocating.

Semiconscious, he thought he was having a nightmare but then realized that the torture was real. At 3:00 a.m., he became completely miserable in “absolute silence. Abandonment, oblivion of mankind.” For the third time in as many days—first when the illness initially hit him, and again the following day—he thought his life was over: “I had the feeling I was giving up the ghost, and I resigned myself to it with complete simplicity.”24

Then, he did one of his typical about-faces. “But the hell with dying; since this is hardly the time for it, let’s try something better.”25 Again he was resolved to reconfigure the settings of everyday human existence.