XXI

1

Raoul La Roche, a Basel-born director of the Crédit Commercial de France to whom Max Du Bois had introduced Le Corbusier, had become keen about the architect’s work. La Roche, who spoke with a thick singsong accent like Le Corbusier’s, was a man of strong opinions. La Roche had been supporting L’Esprit Nouveau ever since 1920, and he valued Le Corbusier, four years his junior, as an aesthetic guide.

In November 1921, Ozenfant and Le Corbusier bought for La Roche six Picassos—“the most beautiful,” said Le Corbusier—and a major Braque at a foreclosure auction of work coming from the collection of the dealer Kahnweiler.1 They acquired for themselves two Picassos that Le Corbusier kept at the rue Jacob and a Braque that Ozenfant had in his studio. The prices, Le Corbusier proudly noted, were a fifth of what they would have been in galleries. Le Corbusier and Ozenfant continued to coach La Roche on his collection, which, while deliberately excluding Matisse, whose pictures they considered lacking in gravity, also had work by Léger and Lipchitz. La Roche was so grateful to Le Corbusier for steering him toward foreclosure sales where art could be bought at low prices that he eventually gave the architect the Braque.

The prosperous banker also bought up work by Ozenfant and Jeanneret—as he continued to be known as a painter. In 1923 alone, Jeanneret sold him six major paintings. That same year, his devotee commissioned what was to be Le Corbusier’s most significant building to date. This was a house in Autheuil, on the outskirts of the sixteenth arrondissement, intended primarily as a showcase for La Roche’s collection and as a place for the banker to give parties.

The project became doubly important because, while Le Corbusier was enjoying new prosperity thanks to La Roche, Albert Jeanneret had befriended Lotti Walden-Raaf, a widow who had come to Paris as a member of the Swedish Ballet Company when it was performing at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Albert and Walden-Raaf were wed in June 1923. Walden-Raaf, who had a private income, commissioned a house adjacent to La Roche’s, where she and Albert and her two young daughters could live.

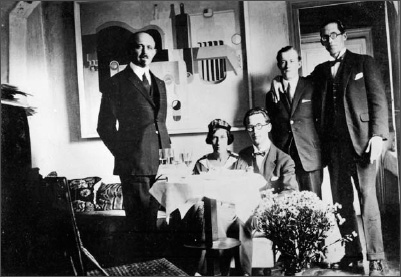

Pastor Huguenin, Lotti and Albert Jeanneret, Pierre Jeanneret, and Le Corbusier at Lotti and Albert’s wedding ceremony, June 26, 1923. Charles-Edouard Jeanneret’s painting in the background, now owned by the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, was his wedding present to them.

The adjoining villas changed forever the way that human beings might choose to feel at home. Notions of what required concealment and what was permissible to see were radically altered; concepts of separation and openness, physical and emotional, were never again the same. The inventive forms and pioneering materials inaugurated a revolution in domestic design that echoed almost everywhere in the world where people construct houses.

THE VILLA LA ROCHE is a marvel of playful rhythms and luminescence. The interior details—the sloping, shiplike interior ramp connecting the second and third floors through the capacious gallery (possibly a prototype for Frank Lloyd Wright’s ramps at the 1959 Guggenheim Museum); the gallery table that is a bold plane supported by an upended triangle at one end and a slab at the other; the recessed shelves here and there; the soaring interior atrium/hall with its lively balconies and ramp ways—have the weightlessness and the upbeat spirit Le Corbusier felt in the music he loved (see color plate 4). The original container was equally daring. As absolute in form as Jeanneret’s most pared-down paintings and more massive than the studio for Ozenfant, it was like an enlarged version of the shoe-box Citrohan houses.

Facade of the Villa La Roche, ca. 1925

With this showcase for an art collector, Le Corbusier opened new possibilities for the concept of luxury. Flat surfaces, machined materials, right angles, sharp edges—all were taken from the realm of industrial fabrication and made the essence of domestic graciousness. A solid block might be as suitable for a rich person as rococo panels; concrete could serve where once there would have been gilding.

THE PROCESS, however, had none of the grace of the results. La Roche had put his total budget at 250,000 francs. By the time construction began, the estimate for building was 200,000, on top of 207,000 for the land and various fees and an additional 80,000 for furnishings and other expenses. Construction began in July 1923, yet the interior elevation drawings were still not complete more than a year later. The interior walls, constructed of brick covered in plaster, were not strong enough to support the doors Le Corbusier specified, which were made of “Ronéo,” an exceptionally heavy metal; some walls had to be rebuilt out of concrete, and the doors’ size had to be altered. The windows had flaws, and the technical systems were a disaster.

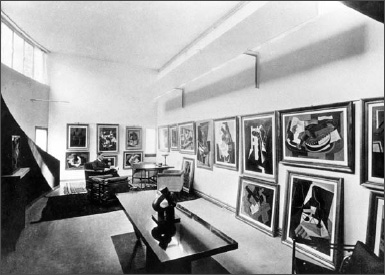

Raoul La Roche with his collection, ca. 1925

The strip lighting Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret designated for the library and gallery gave insufficient light for reading. In October 1925, La Roche wrote Le Corbusier that the dining room ceiling was still “full of holes…. It’s six months since I moved in and I am still obliged to use illumination which…relies on ad hoc arrangements. What must the many visitors think, and what do you want me to tell them? I come back to the point that a perfectly banal system would be the best solution.”2 It was only in further revisions, undertaken in January 1926 and then in 1928, that the lighting was satisfactorily resolved.

Such disagreements—and on many occasions a schism between architect and client—became the norm for a commission by Le Corbusier. Yet the airy court of the Villa La Roche, with its ramps and parapets and sequence of visual vignettes, remains a triumph.

2

The Villa La Roche led to a dispute that sundered Le Corbusier and Ozenfant. Le Corbusier credited himself and Pierre with installing La Roche’s paintings according to the collector’s “precise instruction.”3 Initially, the cousins had hung the Picassos in the gallery, but when the collector insisted that it be used solely for Purist works, they reinstalled La Roche’s collection. When Le Corbusier subsequently arrived at the villa to discuss an unrelated issue, he found that Ozenfant had made major changes in that hanging.

Le Corbusier’s subsequent letter to Ozenfant about the problem exemplifies the insidious form of diplomacy that became his speciality. The architect presents himself as the paradigm of balance and even temper. Touting his own virtue but seeming amenable to compromise, he is initially solicitous; then, subtly, he begins the attack. He writes, “Nothing could please me more than that you should carry out the hanging, but I would like it done by agreement with me—not with the aim of protecting my own interests (since you will have seen that I kept a good place for you)—but simply with the intention of insuring that the La Roche house should not take on the look of a house of a (postage-stamp) collector.” Following that deceptively gentle language, he shows his will of iron: “I insist absolutely that certain parts of the architecture should be entirely free of paintings…. Since this intention appears to have been modified by the new arrangements which you have made, I appeal to you as a good friend, first to take note of it and secondly to come to an agreement with me over it.”4

Then, in 1926, Le Corbusier wrote an article in Cahiers d’Art criticizing La Roche for undermining the impact of his architecture through the dense installation of the pictures. This prompted La Roche to write the architect a charming riposte: “Do you recall the origin of my undertaking? ‘La Roche, when you have a fine collection like yours, you should have a house built worthy of it.’ And my response: ‘Fine, Jeanneret, make this house for me.’ Now, what happened? The house, once built, was so beautiful that on seeing it I cried: ‘It’s almost a crime to put paintings in it.’ Nevertheless I did so. How could I have done otherwise? Do I not have certain obligations with regard to my painters, of whom you yourself are one? I commissioned from you a ‘frame for my collection.’ You provided me with a ‘poem of walls.’ Which of us two is most to blame?”5 Not all of Le Corbusier’s disputes with his clients were handled in such gracious tones.

But Raoul La Roche was a man of exceptional humor. Violaine de Montmollin, the seven-year-old daughter of another of Le Corbusier’s Swiss banker friends, Jean-Pierre de Montmollin, was invited, with her brother, to the formal inauguration of the villa in 1927. The little girl found Le Corbusier, with his strong mountain accent, amusing and extremely charming to her in particular. While others drank champagne, the two de Montmollin children continually slid down the gallery ramp on their backsides; Raoul La Roche and Le Corbusier were the only people present who approved.6

3

Le Corbusier chose the furniture and interior fittings for the Villa La Roche: white curtains, a blend of flannel and cambric, from the department store Printemps; graceful bentwood Thonet side chairs throughout; classic French garden chairs for the roof garden; leather armchairs from the designer Maples. The client mostly acquiesced, but not always. Sometimes, he initially tolerated something he did not like but then changed his stance. In December 1927, when pipes in two of the gallery radiators burst in a cold snap, the complicated repair required rebuilding the wall that supported the gallery ramp, and La Roche used the occasion to change the floor covering.

It was in this period that the remarkable marble-topped table, nesting on a V-shaped tubular-steel support and a tiled miniature wall, appeared in the gallery. In a splendid embrace of modern technology for domestic design, the parquet floors were replaced with pink rubber made by a company called Electro-Cable. Lighting fixtures that looked like gigantic arms were installed. By this time, Le Corbusier and others in his office had become more active in creating furniture and lighting, and the Villa La Roche was a showcase for their snappy new designs. La Roche was the epitome of forbearance, graciously dispensing substantial sums of money to improve his house. In February 1928, the client received a cost estimate of nearly thirty-three thousand francs for revisions; by the end of the year, he had spent almost fifty-one thousand.

Within the next decade, the banker from Basel shelled out even more substantial funds to repair or replace items that should have functioned correctly initially. When the handsome, modern windows failed to shut properly, he paid for replacements. The roof leaked, threatening his precious collection; he had it fixed. The coal-burning boiler Le Corbusier had designated was never sufficient to heat the large spaces of the house; La Roche replaced it with an oil-burning one that, alas, was noisy, smelly, and also inadequate.

Then Raoul La Roche had his patience tested even more severely. He felt cold dampness on the sleek white walls of his gallery; the smooth continuous surfaces the architect had given him had become a breeding ground for mold. Knowing that a creeping incursion of blue fur would have followed, the collector insulated the gallery walls with panels of isorel—a trademark hardboard. It was less aesthetically pure but sufficient to stop the slime.

There was no rage or talk of legal action that today would occur between a wealthy client and his impractical architect. Because of the problem with condensation, La Roche simply relined the space he had already rebuilt once following the radiator disaster, and he rehung his art on walls that now had seams. The pristine had to yield to the practical, and that was that.

Master bedroom of the Villa La Roche, known as the “Purist Bedroom”

IN THE COMPLETE WORK, Le Corbusier described the Villa La Roche as “an architectural promenade. You enter: the architectural spectacle immediately presents itself; you follow an itinerary, a great variety of prospects open; you enjoy the afflux of light illuminating the walls or creating shadows…architectural unity…. The assertion of certain volumes, or, on the contrary, their effacement…. Here, living again before our modern eyes, the architectural events of history: pilings, vertical windows, roof gardens, glass facades. Still, you must know how to appreciate, when the time comes, what is presented and you must also renounce things you have learned, in order to pursue truths which inevitably develop around new techniques instigated by a new spirit born of the profound revolution of the machine age.”7

The villa in Autheuil, sleek and modern on the outside, also has, in its interior, a religious dimension. The large open space is a paraphrase of a cathedral interior. The small balconies that jut into it resemble pulpits. Light floods in from above. With the whiteness, boldness, and simplicity, the building offers a spiritual awakening.

Le Corbusier’s roof garden for Raoul La Roche is also a setting for reverence. The large terrace on top of the villa, with its cantilevered overhangs and smokestack-like chimneys and immaculate tiles, is the stage for a rich array of plantings that present the luxuriance of nature. Le Corbusier had organized the “arbor vitae, cypresses, okubas, euonymus, Chinese laurels, privet, and tamarinds” with even greater care than the paintings downstairs.8 One of the architect’s proudest moments was when his client invited him to see his lilacs and exclaimed, “There are more than a hundred clusters of bloom!”

This more than anything was Le Corbusier’s goal: to bring sunlight, and the natural growth it facilitated, into urban life.

NEVERTHELESS, the architect was not totally satisfied. In his own words, “The plan seems tormented, because certain brutal constraints have required and strictly limited the use of the site: the constraint of non-edificandi, age-old trees to be respected, constraints of height. Further, the sun is behind the house, the site being north-oriented, so that it was necessary, by certain stratagems, to look for the sun on the other side. And despite this torment imposed on the plan by antagonistic conditions, one idea obsesses: this house could be a palace.”9 He was heading toward that dream; orienting himself toward the sun, Le Corbusier was soon to build its palace.

4

Passion can create drama out of inert stone.

—LE CORBUSIER, Toward a New Architecture

When the first edition of Toward a New Architecture came out in 1923, on its cover and title page the name given for the author was “Le Corbusier–Saugnier.” With their new names combined, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret and Amédée Ozenfant left behind their individual personalities as readily as they discarded ornament and brownstone. That attitude changed with the appearance of the second edition, a year later, which cited as its author Le Corbusier. It was, however, now dedicated to “Amédée Ozenfant.” In the next edition, that dedication was removed.

Beyond the disagreements over the Villa La Roche, there had been further discord between Ozenfant and Le Corbusier because of Ozenfant’s infatuation with Surrealism, which Le Corbusier mostly disdained as poorly executed and self-indulgent. Then Ozenfant designed his own dress boutique, for which he used the name Amédée. Le Corbusier considered this emporium a frivolous endeavor.

Le Corbusier told Ozenfant that the lack of dedication in the third edition of the book had been a mistake on the part of the printer. Ozenfant responded that La Roche and Lipchitz had told him that Le Corbusier had deliberately thrown it out. Then Le Corbusier wrote one of his vituperative letters. After voicing concern for the health and well-being of “mon cher ami,” he lambasted Ozenfant for his connection to the world of fashion, accused his former hero of vanity and selfishness, and labeled him a dilettante jealous of Le Corbusier’s greater abilities. Now that he had a live-in girlfriend and a burgeoning architectural career, the symbiotic relationship that Jeanneret had so cherished when he was serving oysters to his soul mate was over.

LE CORBUSIER achieved his objective concerning the authorship of Toward a New Architecture. Today, the book is considered his alone, although both men wrote the Esprit Nouveau articles that comprise it.

An attack on almost all current architecture, this entreaty for a fresh approach proposes a revolution based on “the Engineer’s aesthetic”: “The Engineer, inspired by the law of Economy and governed by mathematical calculation, puts us in accord with universal law. He achieves harmony.”10 With that equilibrium derived from necessity, architecture can give a sense of order, move our hearts, increase understanding, and induce “plastic emotions.”

These wonderful occurrences depend on the use of simple forms arranged systematically, according to a well-conceived plan. It is requisite for the architect to listen to materials and suppress his own ego to achieve balance and rhythmic harmony, qualities elusive in everyday life. Airplanes and automobiles and boats succeed brilliantly because of their designers’ knowledge of the impact of materials and their awareness that the exterior must be determined by the requirements of an interior designed on human scale. All machines for living should be built for the creatures whose living they are meant to improve.

In the era when Bolshevism, Fascism, and Nazism were all on the rise, the book accords architecture the power of a political movement that can provide the solution to all of society’s problems: “It is a question of building which is at the root of the social unrest of to-day: architecture or revolution.”11 Photos of Le Corbusier’s own work are used throughout the book to illustrate that he and his buildings were the salvation of humanity.