XXVI

1

Following the brutal slap of the League of Nations, Le Corbusier was heartened to be endorsed on other fronts.

In June 1928, CIAM—the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne—was founded, with Hélène de Mandrot its main patroness. The new organization was launched at the Château de la Sarraz in the canton de Vaud, of which de Mandrot, already a Le Corbusier supporter, was the chatelaine. A painter, architect, and interior designer—and descendant of a grand family—de Mandrot was a strong, imposing woman in her midfifties who wore her hair in a chignon and dressed in lavish ball gowns or expensive tailored suits and large hats. The eleventh-century structure where this colorful heiress graciously received twenty-five modern architects, as well as industrialists, politicians, critics, and artists, was a multiturreted affair with a valuable collection of furniture and paintings, a perfect place to combine old wealth with new art.

Le Corbusier was responsible for the program of CIAM’s first meeting, which tried to codify advances in building design all over the world. The major issues of architecture were to be addressed: the nature and potential of modern techniques, the relationship of the state and corporations to building programs, the value of standardization, and questions of urbanism, economics, and education.

CIAM’s ideology called for a redistribution of land and the sharing of profits between owners and the community. At a time when Le Corbusier was already under attack, this fueled the rumor that he was a communist. He was as interested in making a luxurious new home for his hostess as in accommodating the masses, but once people got a whiff of what could be construed as socialism, there was no convincing them otherwise.

IN JULY, Le Corbusier and Léger went to the villa at Garches, where the renowned painter was completely “estomaqué”—one of Le Corbusier’s, favorite words—and told the architect that the house was a masterpiece.1 Then Le Corbusier’s burly colleague offered an even more significant endorsement. After a visit to the architect’s studio, the generous-spirited Léger, whose canvases were selling for forty thousand francs, proposed an even exchange of paintings.

Le Corbusier was on a high. He had recently taken an inspiring trip to Spain, and was working on urban plans for Tunis and Buenos Aires as well as on several houses. He was now prosperous enough to treat his mother and Albert to an eight-day holiday together in the mountains, planned for September.

But try as he might to restrain his fury over what had happened in Geneva, he could not obliterate it. Thanking his mother for a letter she had written to comfort him, he continued,

I have a furious rage against these bastards for what they have done and permitted to be done, and I am profoundly outraged, and perturbed by the blinding desires for “justice” by means of which the comedy has been rigged. That I will not swallow. And when I think of the problem itself, handsome as it is; when I see, as I do this evening, for instance, the photos of the splendid site, then all over again I suffer fits of indignation, of imprecations against this huge coalition that has crushed us with weapons having nothing to do with architecture. Nothing to do with architecture. There is the entire drama.

A work so majestic seems to me incapable of being achieved on the basis of so many dirty tricks, which have become flagrantly public. I do not expect an immediate vengeance on the part of heaven. But one may grant that the measure has been so forced that the evil will fall back upon itself.

These people who are making the Palace are mountebanks, businessmen licking the boots of the Academy. Where is the lively, lofty, disinterested, passionate spirit that can carry out this task by an intense love of architecture? These people are “architects” in the dreadful sense of the word. And already they are fighting among themselves.

Our time had not come, nor were we wanted! We were hated because we had raised ourselves to the highest degree of prominence.2

His one remaining hope was that his mother understood this.

2

Le Corbusier was appointed the French delegate to a conference in Prague, where intellectuals from various fields were to converge. To get there, he traveled in an airplane for the first time. He was thrilled to be at the technological frontier.

The architect boarded the great machine with its wide wings and propeller engines at Le Bourget. After a stop in Cologne, it landed in Berlin, from where he took the train to Prague. “We started exactly on time and, miraculously…we arrived exactly on time.”3 This was high praise from a child of the watchmaking business.

On the second evening after he arrived in Prague, Le Corbusier was out drinking with friends in a bar. The poet Vesvald suddenly stood up and shouted out, so that everyone could hear, “Le Corbusier is a poet!” The travelers and businessmen and other strangers in the bar downed their drinks in toasting this idea. “That night I had my first and my profound reward. In vino veritas.”4

On the other hand, when the Czech foreign minister, Edvard Beneš, addressed him as “Maître,” Le Corbusier replied, “Be careful, no nonsense, you’re going to convince me I’m an academician!”5 A poet, yes; part of the established hierarchy, never.

HE WENT to Prague because he was on his way to the recently formed Soviet Union. The people who already believed Le Corbusier was sympathetic to communism now became further convinced.

In May 1928, Le Corbusier had been asked to enter a design competition for the Centrosoyuz—the central office of cooperatives in Moscow. In July, he had submitted the design. In L’Esprit Nouveau, Le Corbusier and Ozenfant had periodically published articles devoted to constructivism and the work of El Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, and Kasimir Malevich, the three most daring and inventive figures in the realm of art and design in the USSR. A reciprocal admiration for Le Corbusier had developed not only among leaders of the Russian avant-garde but also in the highest political ranks; as early as 1923, Ilya Ehrenburg wrote the architect reporting that “in one of his latest articles, Trotsky has spoken in highly sympathetic terms of the trends reflected in L’Esprit Nouveau.”6 Architecture periodicals reproduced Le Corbusier’s latest buildings. Malevich had written a magazine article praising Le Corbusier’s Stuttgart houses for “having borne in mind the needs of contemporary man” in their scale and furnishings.7 His championship had great value, for with his brave and utterly simplified abstract paintings—and then in his return to figurative art that honored the country’s ordinary citizenry—Malevich had achieved heroic stature.

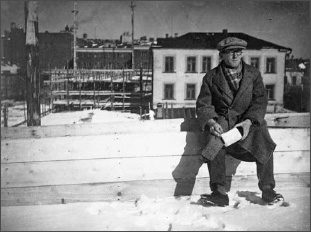

On the building site of the Centrosoyuz in Moscow, 1930

Shortly after his arrival in Moscow, Le Corbusier was received at the Kremlin by the vice president of the USSR, M. Lejawa, and by Trotsky’s sister, Olga Kameneva. A few days later, three prominent Moscow architects addressed a postcard to “Madame Jeanneret-Perret” at La Petite Maison with the message: “Madame, the architects of Moscow offer their affectionate respects to the mother of the world’s greatest architect.”8 For ten days, he was celebrated at banquets and parties. Everyone seemed to be campaigning for the acceptance of his Centrosoyuz design. If Geneva spurned him, Moscow applauded—and gave him reason to believe that at last he would truly realize a substantial building complex with which modernism could triumph at a seat of world power.

3

In a lecture on urbanism “in the great hall of the Polytechnic Museum, the headquarters of the Association for the Promotion of Political and Scientific Knowledge,”9 Le Corbusier presented his Moscow equivalent of the Plan Voisin. He told the large and influential audience “that Moscow was still an Asian city, which it is necessary to care for by building new pavements and demolishing old houses, yet leaving old monuments in place. It is important to enlarge our parks and gardens, shift the business center elsewhere and, by surgical elimination of all side streets, lay out new ones beside existing main streets and line them with skyscrapers.”10

He attacked the current preference for classical revival architecture over modernism: “I find Moscow in the same trance as our Western nations…. It is a criminal mistake to resuscitate things of the past, for the result is not living organisms but papier-mâché ghosts.”11 Le Corbusier pitched the idea that traditional academic architecture—of the type that had prevailed with the League of Nations—was the equivalent of the czarist regime. The visual revolution he championed was as radical as the political revolution in which his audience had participated. Surely they should make the leap in aesthetics, too.

Le Corbusier worked intensely for a number of days with a team of architects who were helping him fine-tune his design for the competition. He was impressed with what he saw in their office. A lunchtime buffet enabled employees to work productively throughout the day, with minimal interruption. When the workday ended at 3:30 p.m., they congregated in clubs, performed in amateur theatricals, played sports, or simply read in an organized environment. This systematized existence appealed immensely to Le Corbusier’s belief in a scheduled combination of work and recreation.

One revelation followed another. In a village a couple of hours from Moscow, the architect saw remarkable vernacular architecture where the izbas (cottages) were built “on pilotis.”12 A Soviet architect introduced him to the film director Sergei Eisenstein, whose Battleship Potemkin Le Corbusier considered a masterpiece. In an interview with a Moscow journalist, Le Corbusier declared, “Architecture and the cinema are the only two arts of our time. In my own work I seem to think as Eisenstein does in his films. His work is shot through with the sense of truth, and bears witness to the truth alone. In their ideas, his films resemble closely what I am striving to do in my work.”13 That goal was unequivocal.

With Sergei Eisenstein (center) and Andrej Burow in Moscow, October 1928

4

One afternoon, Le Corbusier was standing on a Moscow street corner, pencil in hand, with his sketchbook open. He was immediately stopped and informed that such drawing outdoors was forbidden. A commissar tried to get him special permission, but failed. Le Corbusier could not tolerate the idea of not capturing things visually. In the following days, he concealed his notebook under his overcoat so that he managed to illustrate, hastily and awkwardly, some onion domes and monuments. But the need to be furtive astounded him. Such restrictions on human liberty were intolerable.

Nonetheless, when he officially presented his proposal for the Centrosoyuz headquarters, the Russians accorded him all the respect he had been denied by the soulless misanthropes who had pummeled his League of Nations idea. Even though he saw flaws in the economic approach—“The system lacks a stimulus, a dynamic factor…. Lethargy is present”—he imagined the Soviet Union as his stage.14

His mother did not like that idea. When Le Corbusier had arrived in Moscow, a letter from her awaited him. Following warm wishes for his recent forty-first birthday, she finally gave him some of the praise he craved, but then proferred advice—which she pinned to the existence of Yvonne and potential children. “You have been a good son, tender, respectful of the memory of a father who died too soon, generous to the mother left behind who takes great pride in your moral qualities and your intellectual gifts. You must maintain your health and not abuse it—not too many late nights, too much work. Now that you bear responsibility for a soul (and perhaps souls), you must not wear out the mechanism; the great years of youth are past; the summer is still warm and brilliant, yet autumn is approaching, filled, it is true, with marvelous promises to those who set their sights high, making every effort to realize an ideal ever held in mind, despite underhand attacks; and who will triumph because they have had faith.”15 Above all, Marie Jeanneret was worried about how he might comport himself in the Soviet Union: “And now there you are in the vast Russia full of such alarming legends. Here, too, I trust in your lucky star and hope that the Russians, an intelligent people, their modern ideas so advanced, will find yours to their taste and will grant you their confidence in this great architectural project. Be careful what you say, don’t meddle with politics, remain an artist who desires to speak solely of his art. I shall rejoice to know you are on French territory once more.”16

When Le Corbusier answered her letter, he was able to tell her, exuberantly, that his scheme for the Centrosoyuz had been accepted. That endorsement made the Soviet Union all the more enchanting: “I am present at the birth of a new world, built on logic and faith, which plunges me into the deepest reflections. I rein in my optimism in order not to see things except as they are. O blind Europe who lies to herself in order to caress her sloth! Here one of the most explicit designs of human evolution is being realized; and what corresponds to generosity here is egoism there. I look, I see, I question, I listen, I explore everywhere this new event; people here are starting from zero and constructing stone by stone. I use the word constructing advisedly.”17

Marie responded practically by return mail that she was “deeply moved by your letter from Moscow. Here and everywhere in our newspapers, Russia has always been represented as degraded—the behavior of the people deplorable, the family debased and childhood abused, and above all intellectuals persecuted—so that I reread 3 or 4 times the letter in which with apparent impartiality you depict that country so differently.”18

His mother sent this letter to Le Corbusier’s apartment in Paris, expecting him to have returned there. Issuing a word of caution about Yvonne, she repeated the sort of admonitions with which he had grown up: “I assume that my dear boy has returned and found peace and affection in the rue Jacob…and that he might even be cosseted and adored (to excess perhaps); I always fear that a person’s character will be spoiled and distorted by such treatment. One is always inclined to enjoy such treatment, and one cannot help enjoying the comfort of being restored to one’s habits, one’s way of life, one’s daily work.”19

As she reeled off opinions, Marie Jeanneret voiced the blend of intelligence and ignorance with which she had reared her family: “You were understood, taken to their hearts, and I rejoice with you that your plans are prized. Bravo! Cultivated Russians have always passed for powerful minds, lively intelligences. They have always rebelled (nihilism) against an autocratic regime they regarded as monstrous. But the Bolshevist leaders are usually Jews of rather low extraction, and the various massacres they have inflicted have certainly rendered them odious. What are we to believe?”20

But for Le Corbusier, as long as the Soviets would let him help design their new world, little else counted.

5

At the very moment that Le Corbusier was hoping to clinch the Moscow commission, El Lissitzky wrote a scathing article about him. Allegedly about the latest version of the Centrosoyuz proposal, Lissitzky’s essay was an ad hominem attack: “The Bohemianism, isolation and inverted snobbery of today’s artists have reached their apogee in France. Given that Le Corbusier is an artist, he is a case in point. Like all Western artists, he feels compelled to be an absolute individualist, and to recognize nothing outside of himself, because otherwise one might doubt his originality, and because originality is the sensation that gives the measure of what is ‘new.’”21

Lissitzky, who had visited the villa at Garches the previous year with Piet Mondrian and Sophie Kuppers, quoted a member of the Stein family who said the villa was more interesting to visit than to live in. He attacked Le Corbusier as a figure of fashion and as the epitome of western decadence: “Le Corbusier the artist (and not the constructor, the builder, the engineer) was commissioned to build a house that is designed to be a sensation, a piece of magic, and the finished product is published in women’s magazines, along with the latest in fashion (cf. Vogue, August 1928).” Lissitzky described the standard Pessac dwelling as having been commissioned by a capitalist and as being “not a building to be lived in, but rather, a showpiece…. [H]e has designed houses that are disorienting to the user, and which he himself would never inhabit. The reason for this is the architect’s antisocial nature, the great distance that separates him from the expectations of the great mass of people. He has affinities neither with the proletariat, nor with industrial capital.”22 Lissitzky was willfully ignorant of Le Corbusier’s underlying sensibility. What Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had observed in remote Balkan villages at age twenty-three—the joy and contentment of the inhabitants—had helped determine his hope of harnessing the honest aesthetics of peasant huts to modern technology.

Lissitzky treated the architect as if he were simply a fraud: “In the work of Le Corbusier, the eye of the painter is everywhere present—not only in his use of color, which he manipulates as a painter, but also at the level of architectural design: he does not materialize his designs, but merely colors them in. His system involved the construction of a frame—a fact that explains why photographs of his buildings give an impression of unity even when they are upside down.”23

Lissitzky, a gifted photographer, had shot, with closed eyes, a detail of the stairs from one of Le Corbusier’s Weissenhoff houses. The image reads like an abstract composition and could be viewed in any direction without gaining or losing meaning. Besides using this as evidence of a fatal flaw, he also pronounced Le Corbusier’s urban ideal as a “city of nowhere…a city on paper, extraneous to living nature.”24

El Lissitzky was not the only antagonist at this crucial moment. Karel Teige, a Czech intellectual who had been a great supporter of Le Corbusier’s and who had reviewed Toward a New Architecture in 1923, now took up the cudgels, accusing Le Corbusier of approaching architecture as if he was designing for visual reasons only, describing a recent Le Corbusier design based on the golden section as “not a solution for realization and construction, but a composition.”25 The Moscow architect Moisei Ginzburg called Le Corbusier’s architecture “poorly defined and purely aesthetic in character.”26

Le Corbusier felt, nonetheless, more welcome than attacked in the Soviet Union: “I thought I would encounter my typical adversaries in Moscow…. Yet in Moscow I found, not spiritual antagonists, but fervent adherents to what I consider fundamental to all human works: the lofty intentions that raise these works above their utilitarian function, and which confer on them the lyricism that brings us joy…. My feeling is that what interests all these Russians is in fact a poetic idea.”27 The country of Pushkin and Tchaikovsky and constructivism would, he hoped, be the place where his own poetic vision could be realized.