XXIX

1

Le Corbusier had been invited to Argentina and Brazil to give a series of lectures and to help develop urban schemes for Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. On September 13, 1929, he boarded the train in Paris for the port of Bordeaux. Albert, Pierre, and Yvonne accompanied him to the Gare d’Orsay.

Yvonne wrote to Le Corbusier’s mother later that day. She was sad to think of his being away for two months and was worried that he might be seasick, but Albert was coming for dinner, and she was going to make him ravioli, one of the older brother’s favorite dishes. They would also have some of the peaches and pears Marie Jeanneret regularly sent to the rue Jacob; “ever so many thanks for all your kindnesses!” Yvonne wrote Le Corbusier’s mother.1

After settling into his stateroom, Le Corbusier disembarked briefly to post a letter to Yvonne before his ship, the Massilia, departed. His porter had won a bet because he had been the first person to board. “Kisses all around, keep your spirits up,” he wrote. “Everything promises for the best. From your dd.”2

Le Corbusier adored the ship. With its architecture based primarily on necessity, it provided a vantage point for splendid vistas. After two days at sea, he sent his mother a letter, which would be mailed from Lisbon, in which he compared the journey to a dream. The Massilia was “a miracle of modern construction and organization.” On this journey that cost only twenty thousand francs round-trip, there were splendid fresh flowers in the dining room, an admirable style of service he termed “marine-française,” and superb cooking.3 How restful this means of travel was; how magnificent the setting! The change from his normally packed schedule thrilled him, and he relished the opportunity to get more than four hours of sleep per night. He was even happier gliding slowly across the ocean’s surface than he had been soaring through the sky. His only frustration was that there was no swimming pool; while seeing water all the time, there was none he could enter.

Le Corbusier decided to work with a private trainer. He was enjoying the people he met on board—an old Argentinian minister and the wife of a great poet, left unnamed, whom he had met initially at the house of the duchess of Dato—and, except for one of his frequent colds (he kept his mother informed of the extent to which his nose was stuffed), life was perfect. He assured Marie Jeanneret, however, that he had not forgotten the problems she was having with the leaks at La Petite Maison. But he begged her to have perspective: “You must realize that life has other purposes. That so many things can change. And above all, that there’s no need to fuss over situations that are immutable. This was always your weakness and Papa’s: a certain inflexibility.”4

After ten days at sea, Le Corbusier penned a second report: “I must repeat my philosophy lessons: take life as it comes, welcoming the good and acknowledging the bad as inevitable. But for yourself, in your life, let the scale tip toward the good,” he instructed. It was his prelude to a diatribe about the haute bourgeoisie who constituted the two hundred first-class passengers: “diamonds and fake diamonds, toothpicks at the ready, etc.” Having tired of the passengers he had initially liked, he had stopped attending the nightly parties: “I am unsociable in ‘bourgeois’ circles. I have a sense of emptiness confronting such people, who have no thoughts or who think other people’s thoughts. Impossible contacts and frequentations.”5

What he did enjoy were the afternoon performances of “théâtre Guignol,” the famous puppet show for children in which the clever Guignol beats the stupid policeman, Gnafron. Anyone who could defeat a bureaucrat was worth watching.

2

With Le Corbusier away, Yvonne dined regularly with his traveling companion of his earlier years, Auguste Klipstein, as well as with Albert and Pierre. But of everyone in Le Corbusier’s circle, her favorites were the couple she referred to as “M. and Mme. Léger,” who invited her to their farm in Normandy. Yvonne loved drinking local milk, eating fresh eggs, and sitting in front of a large fire with these good-natured people who made her loneliness more bearable.

Once Le Corbusier was in Buenos Aires, his days were charged from early morning to late at night. He gave lectures to university faculty, had tea with the American ambassadress, and met prominent people, among them Victoria Ocampo, for whom he had begun, in Paris, to design a large house on a beautiful site on the Argentinian coast.

Le Corbusier considered Ocampo one of his most enlightened clients to date. He had met this sophisticated and well-connected rich woman in Paris after the Comtesse Adela Cuevas de Vera had written to Le Corbusier on her behalf in August 1928. Ocampo had told him that she wanted a house like his villa at Garches; she also had organized his upcoming lecture tour. The design he gave her was full of his and his associates’ new furniture designs, with a wonderful large salon and dining area punctuated by columns and a form at its center that resembled an igloo, which contained the bathroom.

Le Corbusier was also developing an urban scheme for Tucumán, a small city in the north. But while Argentinian high society and selected individuals were on his side, the Argentinian government was not receptive to his proposals. His new hope lay farther away. The American ambassadress suggested that when Le Corbusier went to New York, where he had a possible skyscraper project, he visit President Hoover in Washington.

Writing his mother from the Majestic Hotel in Buenos Aires, Le Corbusier believed, or hoped his mother would believe, that this interview he expected to be granted with the new president would enable him to discuss yet again the “world city”—meaning the League of Nations.6 Perhaps it was not too late for him to win the Geneva commission after all. And in America there was no end of potential for his ideas on urbanism.

The United States was the land of promise. The secretary at the American embassy was “an immigrant of Slavic origin, extremely intelligent, very strong, a splendid type. As for Oklahoma, I’m told that these westerners are remarkable, taking very practical views so that now there’s a tremendous new development in the far west. Both of us feel that here on American terrain everything works amazingly well. Tremendous power, though lack of culture.”7

Attracted as he was to what was raw and uncouth—and having settled on Oklahoma as his image of a place of pure unfettered energy—for the moment Le Corbusier was impressed with himself for having made it into the refined bastions of upper-class Argentinian living. He had lunch at the Buenos Aires Jockey Club—he told his mother it was the wealthiest in the world—where paintings by Corot, Monet, and Goya hung on the walls. He mocked the pretentiousness, but he was proud to be invited.

Once again, the adventurous architect flew in an airplane and wrote his mother about it: “Tuesday night [October 23], got up at 2:30 a.m., then the plane took off for Paraguay, where I had been invited. First trip made with visitors. We are ten. Average speed: 220 km an hour. This plane is the new model, making its first major flight, a crossing of 1200 km, altitude 500, 1000, and 2000 meters. Amazing trip over the center of South America. Colossal rivers widened by flooding: they seem to be bays. The experience of a virgin nature. Plains of complete silence, meandering rivers and their constant modifications. Here and there, checkerboard cities, farming, cattle. Palms, groves, herds of cows, horses. Water everywhere. Images we traverse, flying under and over. Disturbing melancholy. Mold! It’s the same mold as in jam pots; no doubt about it, mold on a huge scale. Asunción, center of Spanish and Indian America. Violent red earth, intense verdure, enormous trees. Yellow and pink violets. Poetry everywhere. The houses are adorable: Le Piquey in the tropics. Le Lait de Chaux and flowers. Pink, red, and yellow facades. Etc. etc. A day and a half. Overwhelming return, pure sky, enormous America!”8

It was one of those moments Le Corbusier periodically experienced—when he was not demolished by anguish. Intoxicated with earthly existence, he was overtaken by a surfeit of joy. He marveled at the ultimate new product of human intellect and impeccable engineering—the airplane—but, above all, at the inestimable magnificence of nature. The exuberance eventually showed up in the best of his architecture—Ronchamp, the assembly at Chandigarh, his rooftop in Marseille.

Concomitant with that effulgence of joy, Le Corbusier hated what was visually or morally corrupt. Mas de Planta, a beach resort, was monstrous, the Argentinian equivalent of the over-the-top French resort Deauville. Yet even there, he could dive into the pure depths of clear water. The product of landlocked Switzerland compared himself, not for the first time, to a porpoise. He could always avoid the abuses of the bourgeoisie by escaping to his underwater kingdom.

3

In South America, Le Corbusier further mastered the lecture technique that he had been developing throughout the twenties in which he memorized the key ideas in advance so as to give an extemporaneous performance like a theater act. The rooms were always crowded. Le Corbusier relished the idea that they were full not only of enthusiasts but of nonbelievers who needed to be convinced; he would wake the dead.

Unrolling his large sheets of paper, explaining his ideas while sketching away with his sure and agile hand, Le Corbusier became further convinced of his own wisdom. By the end of the Latin America tour, he was so pleased by what he codified in the ten lectures he gave in Buenos Aires and Rio that they became a summa on the functioning of cities.

AT THE END OF October, Le Corbusier again wrote his mother from the Majestic Hotel in Buenos Aires. Heading toward Patagonia, marveling at the tropical climate, he was elated: “How easy my life is here, I’m received by only the highest society—young moreover—and eager-minded. Great luxury, everything comfortable.”9

He recounted a litany of successes. Plans had advanced to organize the meeting with President Hoover and rekindle the Geneva project; the French ambassador had attended all ten of his lectures. The previous Sunday, he had been at a rural hacienda with a splendid garden and a white ceramic swimming pool into which he had dived from the four-meter diving board, “impeccably,” six times in succession: “That’s all there is to it: I’m a good fish. Which for me is an extremely enjoyable situation.”

He would, he told his mother, be making Buenos Aires “the counterpart of New York.” It was his most ambitious urban scheme to date, and he felt that in little time he would have a similar success in the United States. “People talk and know what they’re saying. And one is heard. North Americans are strong and young. Simple and not tricky. For them everything is action. In architecture they are completely backward. And then, they believe. I suspect my next voyage to the United States will be an important thing.”10

Even in remote locations, Le Corbusier was now receiving lecture fees of one hundred thousand francs. And he was traveling in style with Gonzales Garrono, a new friend who was, Le Corbusier wrote his mother, “from the oldest family in Argentina” and a descendant of a viceroy.11 For Le Corbusier, Garrono was the real thing: an aristocrat of impeccable style and bearing, cultured and educated, who was down-to-earth and who spoke to his valet as if to a brother. Garrono took him to one of his vast plantations, which had thrilling twelve-meter-long serpents. But for all the time he was spending with the grandest families, Le Corbusier insisted his head had not been turned: “Dear Maman, I don’t want this to seem like a fairy tale. I remain a modest fellow, longing for his 20 rue Jacob, his oil painting, his faithful companion Vvon; see you soon my dear Maman. If I accept this vagrant life it’s because I may make the kind of money here that will allow me to spread a little comfort around me, to my dear ones who lack the same occasion to make ‘big money.’”12 The term “big money” was in English, for it was America, the land of flashy millionaires, where Le Corbusier expected to earn enough to guarantee his mother and Yvonne and Albert the security and well-being he longed to give them. Writing these words on the day of the New York stock market crash, Le Corbusier was now confident that nothing could shatter his dreams.

4

Writing his mother five days later, Le Corbusier was even more manic: “To sum up, these are remarkable countries with gigantic tasks. They build everywhere, the cities are bristling with skyscrapers, money is flowing. Each private house costs from three to eight or nine million francs. In the provinces there are whole cities to be built. Room for millions of men. They think that Argentina is smaller than France. It may be bigger than Europe. Fertile to the highest degree.”13

Marie responded by pointing out that, because of the language difference, his lecture audiences didn’t understand everything he said. She also cautioned him against being seduced by the splendid style of his new life: “My dear boy, we think of you all the time, we envision you telling a lot of things in French to these Spanish Argentines who perhaps will not understand much of what you say. Be simple and do most of it on the blackboard…. Yesterday morning the great happiness of your letter, your excellent letter, read and reread! So happy that this great journey has left you with such pleasant memories…. Why don’t you write a few of your impressions of the high seas! You have a good heart, and all this luxury will not corrupt our dear child. You must be strong in order to resist; but he who yields to the soft things of life sees his energies diminished and you need all yours, by Jove, in the great battle of life.”14

However splendid her son’s reception was, Le Corbusier’s mother wanted to make sure of his priorities: “My dear boy, you won’t forget Europe, its inhabitants, and the little old Maman with white hair who longs for her boy and for the good news that will invigorate and reassure her.”15

5

By the start of November, Le Corbusier had met Josephine Baker. Le Corbusier had just turned forty-two; Baker was twenty-three. She was already a legend in Paris. Four years earlier, on the stage of the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, the same setting where Charlotte Perriand had seen her clad in bananas, the Missouri-born mulatto had appeared naked except for a pink flamingo feather as she performed splits while being carried upside down on the shoulders of a large black man. That was not the sort of thing people forget.

The poet Anna de Noailles—with whom Le Corbusier had had lunch in Paris the previous year—described her as “a pantheress with gold claws.”16 Baker was renowned for taking Chiquita, her pet leopard, for airings on the Champs-Elysées. At the Folies Bergère, she sang “in a high-pitched warble, with an unashamedly Churchillian accent” and walked backward on her hands and feet, all four limbs stiff like a monkey’s.17 Crowds loved her, and so did the men with whom she jumped into bed—among them, it was reputed, the writer Georges Simenon and, the first time she stayed in a Paris hotel, a room-service waiter. Her husband, Pepito Abatino, was not an obstacle to her freedom.

Abatino was with Baker when Le Corbusier had his first encounter with her. The rapport was instant. We know this because Le Corbusier yet again made his mother privy to his experience. On November 4, from Buenos Aires, he reported that he had just met Baker and Abatino and that Abatino had proposed that Le Corbusier design a house for them in Passy, on the Right Bank not far from the Trocadéro.18 Abatino also discussed their intention of creating a village for orphans from countries all over the world, and he asked Le Corbusier to look for land where they might establish it. Baker, whose success had earned her a small fortune, wanted the architect to undertake a series of maisonnettes for the village. Her vision of that housing was in many ways the Corbusean ideal: straightforward in design, livable, and with a preponderance of vegetation.

Le Corbusier excitedly quoted Baker and Abatino’s vision verbatim to his mother. These dwellings were to be “charming, small and without pretension, amid all the flowers and all the green.”19 With that exquisite notion and Baker’s vivaciousness and allure, Le Corbusier was instantly conquered.

He described the famous dancer and singer: “Josephine is extraordinarily modest and natural. She is actually a Creole village kid, with the warmest imaginable heart. Not an atom of vanity or pose. Really a miraculous phenomenon of naturalness.”20 These were the human qualities he prized above all else. In tandem with a beautiful body, they beckoned irresistibly.

6

The man who told all, or almost all, to his mother wanted to make sure not only that she learned of his adoring friendship with the legend of Paris’s naughtiest music halls but that the good Calvinist had a clear picture of her son boozing and smoking.

Some Belgian visitors to Buenos Aires who were great admirers of Le Corbusier’s were thrilled to recognize him one evening in a restaurant. They asked the architect out for a drink. He turned them down politely, but when they persisted he decided he could not refuse. After the first drink, he again tried to take off, but then one of them said, “You are Le Corbusier. The founder of the Modern Movement. The apostle, etc. Being with you is one of the great days of our life.”21

The Belgians proceeded to drink themselves close to death. They got into a brawl, and the bartenders threw them out. None of this bothered Le Corbusier, who took one of his worshippers to his hotel for a nightcap. After only three hours of sleep and with a hangover, he still managed to meet with Victoria Ocampo the next morning to discuss her villa. He proudly told his mother that by doing gymnastics and swimming laps in the hotel pool that morning, he had overcome the effects of alcohol. Garrono informed him that everyone in Buenos Aires wanted him to build for them; all was for the best. His mother had instructed him to “invigorate and reassure her” quoting the strangers who recognized him, describing his packed life, telling her about Josephine Baker, Le Corbusier had provided the information he hoped would have the desired effect.22

FROM BUENOS AIRES, Le Corbusier went to Montevideo. He adored this city on a coastal hill. It was bathed in intense light and had immense beaches from which he could swim in the sea. While Buenos Aires was possessed of a “fierce austerity” and a “fatality,” the joyful capital of Uruguay had a liveliness that reminded him of the three very disparate cities of Barcelona, Prague, and Moscow. The locals, who received him like a messiah, organized large parties in his honor, and he gave two lectures. The only thing that bothered him was the incursion of Germans.

Enthralling as Le Corbusier found his new audience, he retained his sense of superiority.

One learns to breathe deeply in these countries. One meditates, one takes it in. But the inhabitants are frightened, are timid; compared to them we are tremendously bold.

The prestige of the Idea is a miraculous thing. Meditation leads to kindness, to generosity, to envisaging things in the light of benevolence and courage. What counts in all these impressions is the immensity of the countryside, nature’s formidable song and sign. One must either believe or despair. Better to believe.23

On November 9, he left Uruguay on a small plane that returned him to Buenos Aires and landed in the harbor there. The voyage was glorious, and he had the satisfaction of having gained new allies. “The departure from Montevideo was very touching,” he wrote, “at the edge of the pier some fifteen architects and students. The speedboat took me with some others to the hydroplane, which had just come from Buenos Aires. Waving our arms we made somatic semaphores. Soon the pier is out of my myopic range. I raise my arm. I still see the fifteen silhouetted against the sky. The speedboat reaches the plane, which we enter through the ceiling. There are twelve of us. The propellers are turning. We make a wide circle, and then we’re out of the water. We’re up in the air. Down below, the pier with the waving arms.”24

He was thrilled that the combination of plane and car reduced this journey from downtown Montevideo to his Buenos Aires hotel room to one and three-quarters hours—as opposed to the twelve it would have been by sea. “Precision and dizzying speed,” he wrote his mother.25 Now that he was on course, it was a metaphor for his entire life.

7

When Le Corbusier left Buenos Aires five days later for São Paulo, however, he again traveled by sea, and in true luxury. The ship was the Italian liner Giulio Cesare. As the son of a viceroy, his friend Garrano had considerable influence and had arranged with the captain for the architect to have the finest cabin on the boat. Le Corbusier explained to his mother that he was traveling in the manner of wealthy cattle barons or diplomats. He liked the treatment but hated the style: “My salon is huge in the purest fake Faubourg-St.-Antoine Louis XVI. Louis XVI! They cut his head off but he takes his revenge with a resurrection which seems to last forever!”26

Le Corbusier had boarded the ship with plenty of time to spare before it was to pull out of the port. Once he was settled in his lavish quarters, he went up on deck. He wrote his mother, “Josephine Baker and her husband arrived five minutes before departure, cheered by a huge crowd on the pier. Standing for about three quarters of an hour in the rain, shouting: Merci, au revoir, Madame. Merci, Madame. Au revoir, Mr. Stoll. (Mr. Stoll, as the tug pulled the ship away from the pier, uttered a tremendous ‘yodel’ and suddenly unfurled the Swiss flag.) Josephine wept, shouting like a little girl: Au revoir, merci, merci, Madame. She is the most authentic little Negro child, simple as an ingénue, extraordinarily simple. A simple hardworking artist in every respect. She arrives in Rio in the afternoon of the 17th and begins her first performance that evening. She finished last night at 11:30, and the ship left port at midnight.”27

With Josephine Baker aboard the Giulio Cesare en route to São Paulo, via Montevideo, November 1929

Like him, she was totally devoted to a task she loved. That dedication to an art that brightened other people’s lives mattered more than anything else (see color plate 8).

8

The architect used the time on the Giulio Cesare to plot his return to France. He charted out his schedule as carefully as he drew a floor plan. On December 9, he would leave Rio on the Lutétia, which would arrive in Bordeaux on December 21. Yvonne and Pierre were to meet him in Bordeaux with a car. Still trying to get his mother to Paris for New Year’s, he proposed to her that she join the party; he would pay for her train ticket from Switzerland. Then the four of them could go to Le Piquey for Christmas, after which Marie could end the year with Albert and his family.

“This proposition is quite serious. Distances in America make it impossible to have epistolary arguments. This must happen: I am writing definitively here. Life is short, we must take advantage of it.”28

LE CORBUSIER PREFERRED the Giulio Cesare to the Massilia, both for its scale and its layout. He was especially conscious of boat design because of his own work that year on the “Floating Asylum” project for the Salvation Army. This eighty-meter-long barge resembled a freighter. Its three equal rectangular blocks with industrial windows housed dormitories with rows of 160 beds. The boat was to be parked each winter in front of the Louvre to “shelter the derelicts whom the cold drives far from under the bridges.”29 In the summer, it was to be moored on the outskirts of Paris and serve as a camp for children.

The asylum was more of a floating building than a vessel intended for long voyages, but some of the principles of nautical design applied. The project enabled Le Corbusier to replicate the tight spaces, the need for buoyancy, and the purposefulness that enchanted him on the Giulio Cesare. For a man who liked to make buildings that were elevated above the ground on pilotis, here was one that was literally afloat.

Drawing of drinking Neuchâtel wine, Rio, Copacabana Bay, 1929

9

Why does Baker’s backside rock the continents? Why have throngs of men been roused and even women’s jealousy is disarmed? Why of course it’s because it’s a laughing backside.

—GEORGES SIMENON

In planning so carefully for his return to France, Le Corbusier had neglected to mention a factor that was probably more than a coincidence. Josephine Baker was also going to be taking the Lutétia. Baker and Le Corbusier had been seeing a lot of each other on board the Giulio Cesare, when he made the decision to be on the same boat as her for a far lengthier crossing.

These details concerning the architect and the stage performer are knowable because of the letters Le Corbusier continued to write to his mother. On their first sea journey together, from Buenos Aires to São Paulo, he reported to Marie Jeanneret, “Tonight Josephine, ill in bed while Pepito pastes stamps in his album, explained the Bible to me: In the beginning God created Adam and Eve. Americans are red because American soil is red and God made men out of the soil. Jesus Christ is a divine man. Religion is good because it teaches love, loyalty, and a kind heart. Jesus did not like priests; he chased them out of the temple. And then she picked up a tiny guitar and sang all her Negro songs. Wonderfully sweet, tender, pure: ‘I’m a little black bird looking for a little white bird.’ She acknowledges only what is noblest in the Negroes. Outraged by the caricatures. She wants to show white people the greatness of the Negroes. From head to foot this woman is nothing but candor and simplicity; she led us down into the third-class hold to see a cat that had had five kittens; she couldn’t tear herself away. After the ‘intelligent’ women of Buenos Aires society, I recognize truth here. Josephine reminds me of Yvonne. They have the same conception of life.”30

Like his Monegasque girlfriend, the woman who danced in feathers was to be appreciated not just by him but also by his mother.

IN SÃO PAULO, the novelist Oswald de Andrade told Le Corbusier, “We study you, along with Freud and Marx. You’re on the same level and just as indispensable to the study of the present social movement and to the establishment of a new community organization, etc.” Naturally, he quoted this to his mother, to whom he explained the significance and potential ramifications of his lectures to important audiences: “Actually a lecture is a real creation, like a successful drawing. It begins with a few sketches scribbled on paper. And the idea develops, is expressed, connects, makes its way, its quality of expression varying with the audience that hears it. There is a tension, a flux of ideas in the lecturer’s mind, and their choice and arrangement becomes his creation. When it’s all over, you realize, by the strange fatigue that overcomes you, that you have made an effort.”31 It was as if he were an outsider wanting his mother to join him in observing the phenomenon they had both created.

The charismatic architect also had more to tell his mother about the gorgeous mulatto entertainer who, like him, was conquering large crowds. In São Paulo, he attended her performances. “Josephine Baker is performing here, flanked by her Pepito,” Le Corbusier wrote. “She sang, a revelation: she is a very great artist. I almost wept, so pure was this art, so full of touching generosity. Her voice, her countenance, her gestures are an intense, total creation. She is lost in a stupid, brutal milieu. Pepito is somewhat aware of this. He would like to reach her level, but he is at the bottom of a hole. Josephine has gained an enormous respect for ‘Monsieur Le Courbousher.’ She gave me a little lead elephant, telling those present at Andrade’s after my lecture: ‘Mr. Le Courbousher is not like other men; I have complete confidence in him, I am at ease, he is a great friend.’ I myself feel that she is an artist of a pure and intense sincerity. A true child. She said in Andrade’s salon: ‘I shouldn’t be here, I should be at the hotel mending Pepito’s socks. He has no socks for tomorrow, poor dear!’ Tomorrow she’s singing at the prison for the convicts who have given her a jewel box made with their own hands.”32

Pepito was in the same category as Yvonne: the sweet and loyal soul of a lower order who needed to be taken care of. Le Corbusier and Josephine Baker required such partners. But they also craved their equals in imagination and intensity.

10

By November 27, Le Corbusier was in Rio de Janeiro. Blaise Cendrars had advised him to get in touch with the commission that was planning a completely new capital city for Brazil; what interested him even more was a variety show in which Baker sang “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby.” The song had been written the previous year for Blackbirds of 1928, the longest-running black musical of the epoch. Dorothy Fields’s lyrics set to the music of Jimmy McHugh emphasized the value of warmth over money. The smiling and beguiling Baker brought that idea to life as she chanted. “I can’t give you anything but love, baby. That’s the only thing I’ve got plenty of, baby.” The unguarded sensualism of that heart-filled performance moved Le Corbusier to the brink of tears.

Within little time, she was singing to him with no one else there.

WHEN JOSEPHINE BAKER was on the stage, Le Corbusier believed that what he was seeing and hearing was in many ways the equivalent of the new architecture to which he had been devoting himself. The singer was ravishing to the eyes. Her performance was as unfettered by tradition and as honest as his designs. It was possessed of the bravery and effrontery of Le Corbusier’s houses and of his writing.

Baker’s dancing and singing had the blunt force and the constant rhythm he sought in his own work. The legs that could jump and do splits and fly through the air embodied the synchronicity of all systems in perfect working order. Physical beauty and impeccable mechanics, heart and intellect, were here allied.

As a youth in Vienna, Le Corbusier had been happier in opera houses and concert halls than at shows of the Secession. He now considered jazz on a par with the masterpieces of Puccini and Wagner: “In this American music that comes from the Negroes there is a lyrical, contemporary quality so invincible that I see in it the basis of a new musical feeling capable of expressing the new epoch and capable also of outclassing the European ways, just as in architecture the European ways outclass those of the stone age. A new leaf turned. A new discovery. Pure music.”33

ON THE RETURN TRIP from Rio de Janeiro to Bordeaux, Josephine Baker and Le Corbusier were alone in his first-class cabin of the Lutétia when she again picked up a child’s guitar, more a toy than a real instrument, and sang, “I am a little blackbird looking for a bluebird.” Critics of her public concerts described her voice as “lilliputian” and compared it to a cracked bell with a clapper covered in feathers; but Le Corbusier had no such criticism.

Strumming her toy instrument in the privacy of Le Corbusier’s stateroom, her sleek bangs curling over her forehead, her large eyes sparkling, her smile wide and radiant, Baker sang,

I’m a little blackbird looking for a bluebird,

You’re a little blackbird and a little lonesome too.

I fly all over from east to the west

In search of someone to feather my nest

Why can’t I find one the same as you do?

The answer must be that I am a Houtou.

The next verse that she sang in her lighthearted and playful but deceptively serious cadences seemed written specifically for Le Corbusier.

I’m a little jazzbo looking for a rainbow too

Building fairy castles the same as all white folks do.

For love of crying, my heart is dying to keep on trying

I’m a little blackbird looking for a bluebird too.

When Le Corbusier wrote his mother about Baker singing on the Giulio Cesare, he had made the main lyric “I’m a little black bird looking for a little white bird.” He had thought it was about him.

WHILE THE SHIP glided across the Atlantic, Le Corbusier did a number of drawings of Baker in the nude. She faces her viewer head-on, totally at ease, smiling radiantly. In one image, she has grabbed her knees with her hands in a sort of Charleston movement. But unlike the flapperesque women who specialized in the Charleston, their figures flat as boards, Josephine Baker, in Le Corbusier’s drawings, even more than in real life, has an exceptionally sturdy, full bosom and large buttocks. Her hips jut out like those of Matisse’s Blue Nude of 1907. Much as Le Corbusier liked Baker as she was, he transformed the exotic sorceress according to his own taste and made her his ideal woman (see color plates 23–25).

In another rendering, Le Corbusier gave Baker a truly primitive face, like the images Picasso and André Derain made resembling African masks. It is not a particularly good drawing. The undistinguished sketch, the cliché of a female savage, makes clear that the man who could be so utterly restrained and neat in his building facades—who could, when he needed to, put everything in its correct place down to the last centimeter—had another side that craved total abandon and wildness: in human behavior, in himself, in women. He abandoned his artistic judgment in the process. He reported a lot to his mother, but at least he didn’t send these drawings to Vevey. Rather, he kept them in his private sketchbook.

Le Corbusier also outlined a libretto for a ballet for Baker. There were nine scenes, including one calling for a modern man and woman and New York, represented by a skyscraper, to dance a one-step until a cylinder slowly descends on the stage and Baker emerges from it, dressed as a monkey. She then changes into a dress and sings until the gods rise. Finally, an ocean liner takes off to sea.

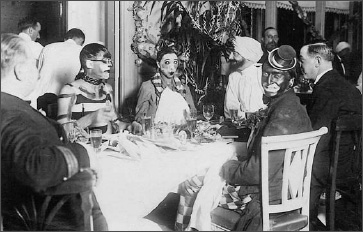

In Indian army uniform, with Josephine Baker in whiteface at his left at a costume party on board the Lutétia, in December 1929

The architect kept the drawings to himself, but he and Baker were very public on board the ship. A committee of first-class passengers had made plans for a costume ball, and Baker and Le Corbusier had decided to go to it together, in spite of the possible embarrassment for Pepito Abatino. Le Corbusier made some sketches for their costumes. In a photo of the two of them side by side—at a lavishly set dinner table with a starched white tablecloth—the architect is in blackface; Josephine appears white. He wears the boldly striped uniform of an Indian army guard; Baker is in a clown’s costume. Le Corbusier sports a polka-dot bandanna. His usually meticulous hair is combed forward in bangs that reach the top of his trademark eyeglasses, making him a total rogue. Baker, with her heavily made-up eyes, is seated on his left, enjoying an offstage moment of unmitigated pleasure.

That the earnest, hardworking architect, normally clad in his dark suit and white shirt, wanted, in his fantasy life, to be a pirate—a cad, a thief, or a con artist—is no surprise. This was just one more mask; he was used to wearing public faces. But a large part of his pleasure had nothing to do with a disguise. The woman at his side had brought him unprecedented happiness.

11

When Le Corbusier later referred to Josephine Baker, he always emphasized that she remained uncorrupted by fame or fortune. The singer was the rare genius possessed of true innocence and kindness. “Josephine Baker, known the world over, is a little child, pure and simple,” he said. “She slips through the cracks of life. She has a warm heart. She is an admirable artist when she sings, she is out of this world when she dances.”34

Josephine Baker wrote about Le Corbusier in much the same way. Her vision of him was like his of her. She found him a pure and gentle soul, enormous fun, and a very serious artist, indeed a genius. She depicts Le Corbusier with a warmth and affection expressed by few other witnesses. But her version of their shipboard romance is played down, with her singing for him occurring in public rather than private: “In Rio we boarded the Lutétia. On board, the architect Le Corbusier. He’s been on a lecture tour. A simple man and gay; we become friends. I amuse him with my little songs, which I sing for him as we walk around the bridge. His architecture of the future seems so intelligent: on the ground, gardens for pedestrians, and the cars up in the air on elevated highways…. But he also says ‘the city is made for men, and not the contrary, Josephine!’ At the masquerade ball when we crossed the equator there were two Josephine Bakers, me and…him. He put on blackface with a feather boa! He’s irresistibly funny. Oh! Monsieur Le Corbusier, what a shame you’re an architect! You’d have made such a good partner!”35

BAKER’S ADOPTED SON, Jean-Claude Baker, has a particular slant on her affair with Le Corbusier: “For her, sex was a revenge. In those days in America you were a colored person from the Negro race, and all those pretty black girls in show business slept with white men at night. Josephine was very angry with white people, and especially white men.” The origin of that rage, her son explained, is that Baker had a white German father whom she never met. Moreover, “white men jumped on these black women—especially on Josephine and on Maude de Forest, because she was the darkest. The men went gaga; it was confusing for those young people.”

Jean-Claude Baker maintains that these motives, rather than pure attraction to Le Corbusier, underlay Baker’s involvement: “She preferred women, because she had been abused as a child. For her, sleeping with men—beyond the revenge—was a way of getting a little security.” As for the men, “They fell in love with the spontaneity and lack of education that she had.”

With Josephine Baker on board the Lutétia

Josephine Baker, her son points out, was beloved in France. She, in turn, enjoyed the respect accorded her by famous French people and the chance to know some of them: “She met Colette and slept with her. She was open, and willing to absorb like a sponge from everyone. Le Corbusier was successful…adventurous, open to the different faces of the world.” In blackface at the party, “he was almost mocking the treatment of black people in America.” The setting was perfect: “A boat is a private island, a floating paradise.”36

There were special points in common. Baker had “built a platform for her bed in her suite in Montmartre,” her son reports. Le Corbusier, too, had high platform beds—as if to put the act of sex on stage. The ship’s bunk suited them well.

12

While Le Corbusier was getting to know Josephine Baker in Rio, Yvonne was growing increasingly impatient awaiting her lover’s return. By the end of November, she had already begun to count the days until December 21. “Poor Edouard, he must be so tired,” she wrote Marie Jeanneret.37

Yvonne was adapting to life as Le Corbusier’s unofficial wife. She continued to visit the Légers often and to spend a lot of time with Pierre. She, Pierre, and the Légers went to the Salon d’Automne together. Here, for the first time, the furniture designed by Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, and Pierre Jeanneret was presented publicly. With Le Corbusier in Rio, she served as a surrogate.

In her lover’s absence, Yvonne painted the kitchen and entrance of their little apartment. She embroidered the stars he had drawn on their bedspread, and she organized a big winter cleaning. Like a diligent housekeeper reporting to an absentee employer, she frequently wrote to Le Corbusier’s mother about these activities.

On December 19, Marie Jeanneret went to Paris so that on the twentieth she and Pierre and Yvonne could go to Bordeaux to greet the Lutétia. Yvonne was happy that the weather had calmed down. It meant that Le Corbusier would have a smoother passage. “His arrival is near, so now I sing all day long,” she had written her lover’s mother.38

ACCORDING TO CHARLOTTE PERRIAND’S autobiography, when the Lutétia docked at Bordeaux, she was also there to greet Le Corbusier. She claimed that her employer strutted off the Lutétia arm in arm with Baker. “Corbu was conquered,” Perriand observed.39

It makes a great story. However, given that we are certain that Yvonne, Pierre, and Le Corbusier’s mother were at the dockside, it begs plausibility. Numerous letters written about plans revolving around the arrival of the boat, as opposed to Perriand’s memoirs published nearly seventy years later, attest to the details. There is no mention of Perriand being there. Perriand, once the others were all dead, used what she knew of Le Corbusier’s truth to enliven her story, adding her own presence, but it was a falsification. Not that Perriand was alone; a slew of characters would, in retrospect, want to make it sound as if they had been more a part of Le Corbusier’s life than they were.

13

Besides the chaise longue, the armchairs, and the visitors’ chairs designed by Perriand, Le Corbusier, and Pierre Jeanneret, the display at the Salon d’Automne also included a revolving metal armchair. Here, the leather cushion is a perfect circle resting on a steel framework that spins freely on elegant, lithe legs. The back seems to grow organically from the base. The support is minimal: a curved cylinder, basically half a circle, made of thick cushioning, covered in leather. Light and taut, the chair provides all that is needed to hold a human being comfortably and not an iota more. Stools—simply the base of these chairs without the back support—were also produced.

A large table, meant for dining or as a big desk, was as simple as possible. A thick, wavy, semiopaque piece of glass rests on suction cups and devices like oversized screws on a minimal but sturdy frame. A series of smaller tables have simple tubular-steel vertical supports and a light steel frame holding clear glass; this concept was developed as both a square coffee table with short legs and a higher rectangular one of multiple uses.

This new furniture was akin to the designs being developed at the same time by Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer, but the Le Corbusier–Perriand–Jeanneret designs still startled their audience in 1929. They are lighter and seemingly less serious than their German counterparts. With their deceptive appearance of weightlessness, they have the charm of a well-executed dance step. They add pleasure to the simple acts of everyday life in ways that eluded the designs made by others. They gave modernism unprecedented elegance.

INITIALLY, LE CORBUSIER and his team had offered their furniture designs to the Peugeot bicycle company, in the hope that, since Peugeot already mass-produced objects of tubular steel joined with rivets, they would want do the same with furniture. But Peugeot turned them down. The designers next approached Thonet, a company that had a new interest in tubular steel. Thonet had already mass-produced a lot of bentwood furniture—including chairs that Le Corbusier often used in his interiors—and had financed the room of furniture at the Salon d’Automne. An agreement was reached for them to produce the new pieces.

However, although these designs appeared in Thonet catalogs into the early thirties, they were not made in any quantity. The world was not yet ready for the flippancy of this furniture. It was to be a long time until those pieces began to appear in thousands upon thousands of public and private spaces all over the world, where we find them today.

14

In 1928, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret had also designed a car. It was not manufactured, and the design was not published until 1935. In its compact shape and the overarching curve from the top of the windshield to the rear fender, the buglike vehicle, called the Voiture Minimum, was the forerunner of the Citroën Deux Chevaux; its rear engine would be echoed in the Quatre Chevaux and the Volkswagen Beetle. Its simple shell-like form was more aerodynamic than was the norm at the time, and it was also relatively lightweight. The car had the efficiency and straightforwardness of Le Corbusier’s most rudimentary housing units.

The idea for the interior was similar to the insides of his buildings: unencumbered space and a lot of glass allowing light to pour in and provide the inhabitants with maximum visibility. The placement of the engine at the back would decrease vibrations, noise, engine heat, and fuel smells. Concerned with the issue of storage, as he always was, Le Corbusier provided considerable luggage space in the front.

This inventive, high-spirited design became another source of resentment. Le Corbusier later believed that the automobile industry stole the idea of his little car. He could never prove the point, but some three decades later when a new Citroën was photographed at Ronchamp, Le Corbusier triumphantly denied the company the right to publish the photos.