XXXI

1

His domestic life organized, his professional life was torn asunder.

Three editorials in a La Chaux-de-Fonds newspaper berated Le Corbusier for his collusion with the Soviets and accused him of taking French citizenship for unpatriotic reasons. The day that he received the articles, he cried. His father’s spinster sister—wonderful, religious Aunt Pauline—still lived in the horrible city, and he could not bear her suffering the ignominy of her nephew’s bad publicity. Then Le Corbusier’s books were banned in Germany, where they were declared to be Bolshevik, and the League of Struggle for German Culture labeled Le Corbusier “the Lenin of architecture.”1 The league’s Nazi affiliation did not mitigate the sting.

Regardless of these attacks and his change of citizenship, the Swiss government forgave Le Corbusier and hired him to design its pavilion at the Cité Universitaire near the outskirts of Paris. And he accepted invitations to travel to Sweden, Norway, and England to lecture and meet with people about urbanism. Le Corbusier also took a long trip to Spain, Morocco, and Algeria with Pierre, Albert, and Léger.

With Léger and Pierre Jeanneret, motoring in Spain, July 1930

He loved Marrakech especially, but developed terrible dysentery on his way home. His mother wanted to treat him with “a milk diet,” a concept he later wrote about even though it failed. What fixed his Moroccan malady, he was convinced, was a civet—“burnt black”—and “wine almost as black” that he and Yvonne consumed on a peak in the Jura.2

LE CORBUSIER was further heartened when he was one of the twelve architects invited to submit a scheme for the Palace of the Soviets. Erich Mendelsohn, Walter Gropius, and Auguste Perret were among the others; for once, he respected the competition. Le Corbusier’s concept evoked soaring confidence and imagination. It called for an enormous and sweeping concrete arch, with the roof of a fifteen-thousand-seat auditorium suspended from it. Perpendicular to the arch, at the other end of the building complex, were five right-angled buttresses resembling oversized angle brackets. A flurry of cylinders and rectangles, vastly different in scale from one another, contained, among other spaces, a second auditorium—for nearly six thousand people—and two theaters. Some of the surfaces were opaque and solid, others translucent. Graceful curves, rigid verticals, gentle horizontals, and long sloping angles, each the by-product of the demands of the interior circulation, combined to give a fantastic energy to the overall result.

The team at 35 rue de Sèvres slaved away at the project. For three months, all fifteen of them stayed at their drawing boards most nights until 2:00 a.m., sometimes even until dawn, and worked every Sunday, too. Le Corbusier considered the teamwork a “beautiful collaboration,” with everyone aware of what everyone else was doing.3 Finally, he insisted that no further modifications would be permitted, and forty meters of plans went off to the Soviet embassy three days before Christmas 1931. From there, they went to Moscow in a diplomatic pouch.

Once the project was complete, Le Corbusier slept until one in the afternoon three days in a row. Exhausted but happy, he wrote his mother, “With all this, a deep inner joy: creating.”4

IN THE MIDDLE of trying to wrap up the Moscow design, Le Corbusier was asked to give a lecture at the Salle Pleyel, one of the most prestigious concert halls in Paris. The event was organized by Architecture d’Aujourd’hui—an organization devoted to progressive building theories that published a review of contemporary architecture in which Le Corbusier was often the subject or author of articles. Le Corbusier used the occasion to talk about the need to plan buildings from the inside out—and to blast those who violated that principle.

One hundred and thirty students of the Beaux-Arts had been invited, but more than five hundred showed up and shouted throughout the lecture. Le Corbusier believed the insurgents were there at the instigation of his old foe Lemaresquier—the man who had called attention to his League of Nations proposal not being penned in China ink—who was one of their professors. The proponents of the belief that buildings required traditional facades regardless of what happened behind them so hated Le Corbusier’s viewpoint that at subsequent lectures numbered cards were distributed individually to the attendees, and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was not invited. Modernism now required security measures.

2

At least he had his loyalists. Le Corbusier was working in this time period on a compact luxury villa in the isolated countryside between the mountains and the sea near Toulon, in the south of France, for Hélène de Mandrot. The heiress, who, in addition to her Swiss château, had a house in Paris not far from the Invalides, was now looking for a smaller modern getaway.

Le Corbusier addressed Hélène de Mandrot as “Chère amie.” He told her he put himself in the category of “men of action and ideals…. We are professionals, prevented at every step from expressing a pure conduct…. Politics? I have no particular identification, since the groups attracted to our ideas are the Redressement Français (bourgeois militarist Lyautey), communists, socialists, and radicals (Loucher), League of Nations, royalists, and fascists. As you know, when you mix all colors you get white. So there is nothing but caution, neutralization, purification and the search for human truths.”5 That openness about his innermost feelings was a mark of respect, but to his mother, Le Corbusier put a different slant on his wealthy client. She was, he told Marie Jeanneret, “as disagreeable as you are.”6 He was thrilled with the house he designed for her—“remarkable, new, strong, solid, splendidly incorporated into the landscape”7—but “the chatelaine is seriously stricken with client disease: acute crisis and lack of sang-froid.”8

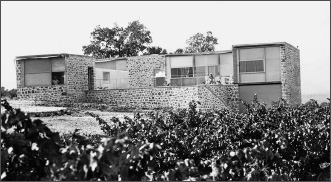

De Mandrot had reasons to be upset. Made of local rocks applied to a reinforced-concrete structure so as to resemble old-fashioned stone walls, the sequence of interlocking geometric forms fits into its setting with grace and harmony, but, like his mother’s house, it leaked. Shortly after the elegant villa was completed, de Mandrot phoned Le Corbusier in a state of high anxiety. She described “a lake” that had formed on her living-room floor during a recent downpour.

The Villa de Mandrot, near Toulon, ca. 1931

Le Corbusier quickly boarded a train to Toulon. When he entered the luxury villa—his suit and bow tie as impeccable as ever—he did not appear the least bit bothered as he viewed the pool of water. He asked de Mandrot for a plain piece of paper. The architect took the white sheet and carefully folded it into a simple toy sailboat. He set the boat down in the large puddle and watched it float. “You see, it works,” he told his client.9

Le Corbusier then studied the construction of the windows through which the water had seeped. They had not been properly fit. He addressed the befuddled aristocrat: “Hélène, you’re an architect. How could you have permitted the builders to get away with this? You were on site. Now, really, get the mistake corrected, and please don’t ever again disturb me with my busy schedule in Paris about something of this sort.”10 He left, and returned to the capital as quickly as he had arrived.

3

In the spring of 1931, Le Corbusier took Yvonne to her birthplace. He reported to his mother, “She’s had a childish delight to be back in her Monaco. And everywhere she went she was made much of by good, simple people.”11

With Yvonne, Le Corbusier then made the first of many visits to Algiers. Initially, the intense sunlight, the hills surrounding the city, and the lush vegetation there made him oddly uneasy. He wrote his mother, “I’ve had too many struggles and misfortunes to be able to contemplate these gardens in Algiers without a certain uneasy feeling. Such radiant harmony and such perfection have a crude aspect wounding to a sensibility hungry for reality; these gardens plunge you into a convention of happiness, they are a stereotype of the beautiful.”12

After Algiers, Le Corbusier and Yvonne went to the Côte d’Azur and then drove back to Paris. The Easter holiday made it nearly impossible to find places to stay overnight, but his wife was an agreeable travel companion. He explained Yvonne’s nature and his strategy for dealing with it to his mother: “once one learns to maneuver around her basic nervousness, which is considerable, she offers the most perfect and delightful good humor. And I have the impression that ever since the mayor officiated, she’s infinitely calmer. As dear Papa would have said, ‘All’s well that ends well.’”13

4

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret were in this time period also making designs for a museum of contemporary art in Paris. They were so fascinated by their idea for this project that they decided to pursue it even knowing there might never be anyone who would support it. Le Corbusier explained the concept in a letter to his friend Christian Zervos. It was to start out as a building without facades, with a single exhibition space, fourteen by fourteen meters, which could be built for the modest sum of one hundred thousand francs.

The visitor was to enter via an underground tunnel. The walls would be membranes, some fixed, some movable, to allow for indefinite expansion in the form of a square spiral growing outward around the core. The issue of what one saw from the outside was virtually irrelevant. Additions could be built at any time; with one mason and one laborer permanently employed, the museum would be in the process of perpetual enlargement.

Le Corbusier assumed that rich donors would underwrite the cost so the people at large could benefit.

The donor of a picture can give the wall where his picture will be hung; two posts, two cross-beams, five or six joists, plus a few square yards of partition. And this tiny gift permits him to attach his name to the hall which houses his pictures. The museum is built in some suburb of Paris. It rises in the middle of a potato field or a beet field. If the site is magnificent, so much the better. If it is uglified by factory chimneys and the dormers of wretched housing developments, that doesn’t matter: by the construction of partition walls we will come to terms with…factory chimneys, etc., etc.

My dear Zervos, such is the concept of our museum, which I have hitherto shared with no one. I’m giving it to you. Now it’s in the public domain. I wish you the best of luck.14

Willing as he was to donate his architectural fees for something he believed in, Le Corbusier was furious at the manner of the bankers who in the same time period caused problems with his Immeuble Clarté in Geneva. The architect’s first apartment building, with forty-five two-story dwellings, the Clarté had cantilevered terraces, industrial windows, stovepipe stair railings, and no ornament whatsoever. Built by Edmond Wanner, an enlightened Geneva industrialist, it quickly became as popular as it was radical. But even after every apartment had been rented, the skeptical bankers who financed the project questioned whether the inhabitants of the building would still be happy there after twenty years. “The bank seems to be claiming that ordinary methods are doomed to an indisputable perpetuity, while everything progressive—and in this instance a particularly far-reaching kind of progressive—is doomed to certain death,” wrote Le Corbusier.15 Nonetheless, the building is still standing today.

5

At age forty-three, Le Corbusier began to dispense expertise even more vociferously than before. “Advance an argument, defend yourself, do not capitulate. Triumph!” he advised his mother, after telling her she must consult professional doctors and stop depending on natural medicine to deal with her frequent bouts of grippe. When Albert complained about the time constraints in completing a musical score, Le Corbusier informed their mother, “I told him: that’s what life is. And that’s how things get done. Someone who creates something always dances across a perilous tightrope. Man is capable of sublimating himself.”16

For Le Corbusier himself, the feeling of walking on a tightrope was increasingly real. Alexandre de Senger was determined to prove that for Le Corbusier architecture and urbanism were merely a pretext, that his main objective was to preach communism and that his buildings were an attempt to further the Bolshevist cause. De Senger published a book, The Bolshevist Trojan Horse; the horse was Le Corbusier.17 Auguste Klipstein gave Le Corbusier a copy shortly after it was published.

De Senger attacked L’Esprit Nouveau as “one of the most important magazines of Bolshevist propaganda,” pointing out that the review was read in Russia.18 Willfully misquoting Le Corbusier, De Senger claimed that in the magazine the architect had referred to the Gothic, Baroque, and Louis XIV styles as “veritable corpses.” In truth, Le Corbusier had criticized the appropriation of these styles but not the styles themselves.19 De Senger also wrote that Le Corbusier had declared rainbows less beautiful than machines—a deliberate misrepresentation of a comparison between rainbows and geometric forms that made no qualitative judgment.

Failing to mention that Ozenfant, too, was responsible for L’Esprit Nouveau, De Senger wrote, “The editor of this magazine was Le Corbusier, from La Chaux-de-Fonds. His most important collaborators are the Jews and freemasons Walter Rathenau and Adolf Loos. Most of Le Corbusier’s other collaborators are also collaborators of the major Bolshevist newspaper Le Monde, edited by Henri Barbusse. Le Corbusier is known for his frequent trips to Moscow where he has received important commissions.”20 It was all either false or misleading, but de Senger’s followers willingly subscribed to his diatribe.

In May 1934, de Senger was to publish an article called “L’Architecture en peril” in the periodical La Libre Parole. Here, too, his means of denigrating Le Corbusier was to accuse him of complicity with Jews: “The allies of international Jewry continue, despite the crash, to intrigue under different titles and programs in order to increase their fortunes and retain their influence.”21 This time, there were no tears. Le Corbusier wrote his mother that he felt honored by de Senger’s diatribes. Such opposition put him on the level of Diderot, the organizer of a revolution, and recognized his influence. For a self-anointed martyr, opposition was the most effective incentive to continue on the path of rightness.

6

Algiers (together with certain other privileged places such as cities on the sea) opens to the sky like a mouth or a wound. In Algiers one loves the commonplaces: the sea at the end of every street, a certain volume of sunlight, the beauty of the race.

—ALBERT CAMUS

From the Hotel St. Georges in Algiers, Le Corbusier wrote his mother at the end of March 1931: “This is a splendid country where the fraternal beauties increase with every feature, from lovely sea to snowy mountains and to the desert. A charm, a light, and the endless attractiveness of the Muslim races. Here, more than ever—as at Rio—my heart is won and takes root.” For fifteen days, he had studied the city of Algiers from every possible angle. “What Paris is in despairing lethargy, this land of colonization is in strength, in needs, in urgency of achievements…. How beautiful the world could be if we brought it into harmony!…Already I feel myself at one with this country; Le Corbusier the African.”22

After returning to Paris, Le Corbusier got word that he was being asked to undertake urbanism in Transjordan. It was a “crescendo”23 work was coming from everywhere. Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius invited him to show the Plan Voisin in a major exposition in Berlin. He was painting, with an exhibition planned for the fall (again making specious his claim of keeping his painting under wraps). He was also writing articles for The New York Times and working away on The Radiant City—a new and thrilling exegesis on urbanism.

Yvonne gave grace and balance to his domestic life. While the architect readied himself for a second trip to Algiers, she made another blouse for his mother out of assembled fabric samples. She was obsessed with finding all the right pieces and tested them for shrinkage. She cooked Albert his favorite ravioli. Le Corbusier wrote his mother, “I am entirely content. Our life flows by in order and good humor.”24

The difficulties were with Marie Jeanneret and his health. As usual, Le Corbusier begged his mother for more mail, accusing her of saving her energy by writing to Albert and not to him. His repeated attacks of sinusitis and chronic nasal congestion exacerbated his irritation, and he became even more upset when his mother began to complain about her house while still refusing to hire a maid. By midsummer, Le Corbusier cracked: “You have always brought passion into these matters. Proclaiming your rights, charging others with bad intentions, nastiness or incapacity. This does not make the work easier; it creates a painful atmosphere. My stays at Lac Leman, ever since the house has been there, have been consistently tormented by this strained atmosphere. It is much more painful than you think. You don’t realize how explosive you are with me, precisely when I need 24 hours of relaxation, you know what I have to deal with every day of my life. If you could give the situation some thought that would be a good thing. You must know I don’t let things slide, but at the same time I don’t try to make everything into a drama. What really annoys me is that in this whole business, from A to Z, I’m the one who receives your reproaches and Albert gets treated as a fine fellow. Believe me I’m not jealous, far from it. But consider the situation a little more carefully and you’ll see what I mean.”25

After all that, he instructed her, “But try to realize that life must be taken with as much serenity as possible.”26

HE NEVER KNEW when the next onslaught would come from either her or Yvonne. In a spell of bad weather, Yvonne again became tired and nervous. In his next letter to his mother, in mid-July, he quipped, “Maman is always seething and …arbitrary, like all temperamental women.”27

In August, he returned to Spain on his own, in part to escape both his torturers. The sights and people in Almería, Andalusia, and Málaga quickly restored his high spirits: “In everything here I sense the awakening of the Latin races, full of strength, health, the intelligence of accurate feelings.” Reflecting about her from afar, he recognized that Yvonne was the essence of the type. On his way to Valencia, he characterized his wife to his mother as “like a little child, devoted, loving, loyal, and very dignified, but morbidly fierce.”28

From Spain, Le Corbusier traveled on to continue his work in Algiers. It was, he claimed, fifty-four degrees, but even though he felt he was “dead from thirst”—so he wrote on a postcard on which he drew a skull and crossbones—he was thrilled to be in a place he loved and away from the two women whose crankiness and disapproval weighed on him more than all the critics and academies and architectural juries put together.29

LE CORBUSIER always had one current undertaking that was the ne plus ultra—a project that would allow him to realize his philosophy in its totality and change civilization. Now it was his major city plan for Algiers, on which he was going full throttle in the steamy North African city that August.

Then, just as he was about to set sail back to Europe, he had some devastating news. Marie Jeanneret’s beloved dog, Bessie, had been run over. After the initial shock, he did his best to summon his sense of perspective: “Dear Maman, you must not interpret the effect of what was a pure accident as a stroke of fate. You must be aware of events, and sensitive to them, but not weak.” He did not, however, trivialize the importance of a pet dog. He told his grieving mother that he had recently come to realize, “I’ve always met my dog’s eyes with my own: dogs are a kind of mirror of tenderness and trust.”30 He craved constancy and affection wherever he could find them.

7

When Le Corbusier turned forty-four on October 6, he received greetings from all over the world; more important, this time his mother did not forget. He responded to her greetings by sending her a summary statement of his life. First, she should know the extent to which he suffered from stomach problems and colds; he was susceptible to sickness because of all the travel and “an intensity of work that knows neither schedule nor calendar…. People who live a clockwork life are more likely to be given a more regular bulletin of health.”31

That reflection prompted one of his anti-Swiss diatribes: “Once over the border one returns, in France, to the country of liberty. What relief, what benign welcoming dust. Switzerland has placed itself under orders I cannot accept, for I am concerned with other things. A Vauxdois customs officer is a monument of brutal rigor and stupidity.”32

Le Corbusier continued his overview: “Life here is calm, agreeable, productive. At forty-four, one needs one’s lair with its hideouts and its raisons d’être. Then everything can flow without a hitch. Yvonne continues to be the understanding accompaniment to my life. That is serenity for me.”33

His mother, however, impeded that serenity. Marie, now seventy-one and still living alone, had fallen down the stairs that led from the new room Le Corbusier was in the process of putting on the house. He implored her to change her ways and hire a maid—which was precisely why he had built a maid’s room there. Le Corbusier considered the accident a result of her intractability and her deliberate resistance to living joyously.

He lashed out at both her refusal to have help and her suggestion that she might have to move:

These dreadful threats are a distortion of your spirit. When we were kids, I remember you always made light of housework, relatively speaking, and concentrated your energy on giving lessons, from which you obtained something for our own upbringing as well as a lively contact with your students. These threats, aside from your personal feelings, are a barrier you deliberately raise against us, thinking (what an illusion!) you could impose your concepts on us, though in such situations they are of no use to us whatsoever.

The Swiss mania for order annoys, disgusts, chills, and scandalizes me.

So all your efforts of persuasion are entirely futile.

And the consequence of this mental distortion is your feverishness, your terror of not being ready, your haste…. And you fall down the stairs.

I know I’m being harsh, and I make no efforts to mask my thoughts. No, this is an unfortunate aspect of your character that I implore you to turn your attention to. Pedantically, may I remind you of Jesus’s remarks on the subject of Martha and Mary.

You see that the case has existed for a long time.

But you who read the Bible and can find something else in it besides Protestant points of view, take a lesson from it for life. There is a choice to be made in life—of the important things most of all. And you, your life, your image, what other people seek from you, is your artistic power, your freedom of mind, your personal, individual interpretation.

Life, life, life. That’s what we all love.

We your children and their friends and companions have oriented our lives in this direction. We have found our earthly happiness there.

You will find yours there as well. Come back to it, the truth is here, and the atmosphere of the lake will be poignant with intensity, clarity, personality. Understand what I am saying: you make threats.34

Dressed as a cleaning woman, on holiday at Le Piquey, ca. 1930

THE ARCHITECT was becoming as discouraged about the state of the world overall as about his mother. As the end of 1931 approached, he believed now more than ever that completely new solutions were required if civilization were not going to continue its downward spiral.

His belief that society barely functioned was exacerbated by a bitter dispute concerning the enlargement of La Petite Maison. The head of public works in Lausanne had written Marie Jeanneret demanding that construction work stop because the necessary permits and permissions had not yet been organized. Rarely had the regulations and silliness of authorities infuriated him more. He wrote the official in Lausanne saying that everything had been done according to the rules, that he had personally met with the necessary people in Lausanne more than a year earlier, that it was impossible to stop construction in mid-November, and that his mother was a white-haired lady who had the right to be left in peace and not to have her health compromised.

Le Corbusier probably had not conformed to the letter of the law in planning the expansion of La Petite Maison. He still believed in his inalienable right to follow his own rules—especially in his capacity as his mother’s protector. In this instance he prevailed, and the alterations to La Petite Maison were completed.

8

Le Corbusier always dreaded the way Christmas and New Year’s threw life off course and led to “communal stupidity.”35 Now married a full year, Yvonne’s expectations for the holidays only made matters worse; having grown up with few comforts, she was both childish and needy. The architect’s greatest problem at the year’s end, however, was knowing that his completed work was in that diplomatic pouch. The thrill of creation was over.

Nothing more was expected or needed, but Le Corbusier could not stop himself. For the next two months, he continued to send documents concerning details of the building. The architect made note of experiments he had undertaken with light waves in order to evaluate the acoustics, and he provided explanations for the reason that flat roofs on top of hot-water pipes were an effective means of melting and draining snow.

Le Corbusier then came to believe that his project for the Palace of Soviets had been “favorably received in all circles in Moscow,…[and] declared suitable for construction” and that it was to be the pinnacle of the current Five-Year Plan.36 He was completely disconnected from reality. On February 28, 1932, a short list of three was announced, and he was not on it.

In Izvestia, the leading Moscow newspaper, Alexei Tolstoy wrote that the “Le Corbusiersianry” resembled “a strongbox—a latter-day feudal fortress—the home of a bandit protected by impregnable walls of gold. This is the ultimate devastation, a refusal of reality, a submission to materials, the cult of materials, fetishism; it is only one step away from the primitive condition of the psychological troglodyte.”37

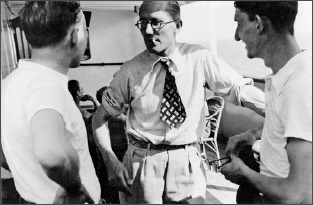

Manipulating the roof of a model of the auditorium of the Palace of the Soviets, in the office at 35 rue de Sèvres, 1934

Lecturing in Barcelona about the manifesto sent to Stalin following the verdict of the committee in Moscow concerning the construction of the Palace of the Soviets. Le Corbusier is speaking to, among others, Walter Gropius and José Luis Sert, March 29, 1932.

The winning design, by Ivan Zholtovsky, resembled an Italian Renaissance city, complete with a piazza and Roman-style coliseum. Le Corbusier declared, “We were expecting from the USSR an example of authority, edification and leadership, since such an example expresses the noblest and purest judgment…. There is no more USSR, no doctrine, no mystique, or anything else!!!”38

Then, in April, Le Corbusier drafted a telegram to Stalin calling the jury’s decision an act of “criminal thoughtlessness.” The scheme chosen for the palace, he subsequently informed the Soviet leader, “turns its back on the inspirations of modern society which found its first expression in Soviet Russia, and sanctions the ceremonial architecture of the old monarchies….[T]he Palace of the Soviets will embody the old regimes and manifest complete disdain for the enormous cultural effort of Modern Times. Dramatic betrayal!”39

When Le Corbusier was then informed that Stalin had deliberately determined that architecture for the proletariat should be Greco-Roman, he decided to sever all ties with the Soviet Union. Although a version of the Centrosoyuz was built, Le Corbusier’s flirtation with the new way of life in Moscow now came to a full stop.

But the controversy surrounding his travels and work in Russia was just beginning.

9

On Monday, March 14, 1932, in the Salle Wagram, a large Parisian auditorium, Gustave Umbdenstock, an architect who was a professor at l’Ecole Polytechnique and head of the studio at l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, lashed out against the leader of the contemporary style that deprived human beings of the joy and optimism for which tradition in architecture was imperative. Umbdenstock accused his unnamed foe of making shoe boxes and vilified him for his use of concrete and his ideas about automobile circulation.

Le Corbusier considered the address an act of war. In response, he wrote Crusade, or the Twilight of the Academies. The small book, which appeared a few months after Umbdenstock’s diatribe, amplified Le Corbusier’s theory that a major campaign against modern architecture was being financed by large building companies, whose management felt threatened by the new technology he advocated. Businesses that specialized in slate, tile, zinc, and wood—rather than reinforced concrete—had joined forces against him and his allies. There was, Le Corbusier was convinced, a complete conspiracy determined to prevent him from realizing his ideas.

THE ATTACKS CONTINUED in a series of twelve articles that appeared in Le Figaro, the most widely read of Paris’s many newspapers. Under the title “Is Architecture Dying?” they were written by Camille Mauclair—a poet, novelist, and critic whose real name was Séverin Faust. He linked L’Esprit Nouveau, the Bauhaus, and other modern movements to Bolshevism and declared Le Corbusier a Bolshevik.

The diatribe inspired a pleasant surprise. One of the people who came to Le Corbusier’s defense was Amédée Ozenfant. Ozenfant wrote the paper a letter characterizing his former colleague’s Russian engagement as a demonstration of French influence “on people who are looking to find a way,” not as an adherence to anything Russian.40

Yet nothing compensated for the pain inflicted by the fate of Le Corbusier’s design for the Palace of the Soviets. The architect had to deal not only with his own disappointment but also with that of the fifteen draftsmen in the office who had worked so diligently on the project. He felt that they had addressed the fundamental issues of circulation, acoustics, and ventilation, only to have these essential matters completely overlooked by the jury. Le Corbusier did not mind the attacks against him in Switzerland and France so much as he regretted the failure of the new Russia to understand the magnificence of what it was refusing.

10

Le Corbusier made his own rules for social behavior. One evening, at about six o’clock, he invited Charlotte Perriand to the construction site of the Swiss Pavilion. The architect pointed out corrections that needed to be made to the emerging structure, and Perriand took notes. Suddenly, Le Corbusier stopped in his tracks and, out of the blue, asked Perriand, who had been divorced two years earlier, how her life was going. She answered that all was well.

Then Le Corbusier blurted out: “Do you love women? I could understand that.”

Sketch based on an Etruscan fresco he had seen in Tarquinia, drawn from memory, June 11, 1934

Perriand’s reply was instant: “Of course not, what an idea!” To this, Le Corbusier replied, “In my studio, there’s a tall boy, Pierre, who dreams about you night and day. Think it over.”41 Then the architect continued the working walk through the site as if nothing had been said.

A few days later, Perriand asked Pierre Jeanneret if Le Corbusier had told him about their discussion. He said that he had and asked Perriand how she felt. She told him she liked her freedom; he replied that he liked his.

Perriand eventually decided to continue the conversation with Le Corbusier. He cut her off right at the start, announcing, “I’m not your nanny.”42 Nothing was ever the same between them again.

11

The Swiss Pavilion, on the outer edge of Paris on the campus of the Cité Internationale Universitaire, has as its core an elegantly cantilevered rectangular slab that stands on graceful, anthropomorphic pilotis. The south facade is a pristine glass curtain wall, the north a clear composition of concrete blocks punctuated by minimalist square windows. Inside and out, there is a medley of sheer curved walls.

Le Corbusier made this vanguard structure, which was completed in 1932, despite spite of being hampered by severe budget constraints. Only three million francs were allotted for it, whereas similar buildings on the same campus were given twice that. He considered his creation of “a veritable laboratory of modern architecture” with such élan, in spite of the parsimony of his resources, a deliberate act of revenge at Swiss miserliness.43

On a curved wall near the entrance, there was a mural of photographs. They showed enlarged images of microbiology and micromineralogy, testifying to the combined wonders of technology and nature. As one proceeds through the building, Le Corbusier’s ability to transform the ordinary is evident in the imaginative lamps and radiators and the energetic arrangement of hot-water pipes; it’s as if he had taken dry, characterless Swiss bread and turned it into a brioche. Through his graceful manipulation of rudimentary components, the students’ spartan bedrooms are light and amusing. White linoleum becomes fresh and mirrorlike; neatly integrated shelves, cupboards, and counters come to life like music.

But it was not well received. Le Corbusier himself was quick to point out that the naysayers were calling for something that more closely resembled a traditional chalet. He compared the inauguration ceremony to a funeral. Following a prosaic speech by a renowned Swiss mathematics professor, the audience had responded with complete silence. The overall style, and the photographic mural with its unusual content, shocked critics.

After World War II, the architect wrote, “In my innocence, I had been guilty of praising the wonders of nature, the glories of Almighty God.”44 “Fortunately” the mural had been destroyed by the Germans, who occupied the building in 1940. Edouard might tell his mother to accentuate the positive, but he still periodically played the role of Sarcasm.

12

The mayor of Algiers gave Le Corbusier free rein to redesign his city. With such a supportive client, Le Corbusier set out to create a plan that could revolutionize urbanism all over the world.

Le Corbusier proposed building upward. Skyscrapers would create space for two hundred thousand or more inhabitants within the city core. The Casbah would remain, but next to it there would be a new financial district, as well as a civic center with a courthouse and other public buildings. A second residential neighborhood would consist of skyscrapers built into the hillside and vast apartment complexes constructed on a 108-hectare property currently covered with vineyards. This plan allowed for the landscape of hills and valleys on the outskirts of town to remain undisturbed, still available for agricultural purposes, while also accommodating swimming pools and parks for walking and sports.

Le Corbusier believed that Algiers could be the fourth and final point of the star that already included Barcelona, Paris, and Rome. His efforts to realize his dream there would, within a decade, lead him inside the corridor of power at one of the lowest points in the history of France.

13

Le Corbusier attended the fourth CIAM, which took place in Athens from July 29 until August 10, 1933. On the day of his departure, he received an anonymous letter at his hotel, signed “X the Greek.” “X” asked, “Without ornament, and with the present-day uniformity of construction materials, can the new architecture manage to express the specific character and the various sentiments of each country? I can see you eagerly answering me yes, and I am absolutely in agreement with you. You speak of geometry as only an ancient Greek could have done. You have opened my eyes, and I thank you with all my heart.”45

“X” was responding specifically to the lectures Le Corbusier had just given, which became the basis of CIAM’s Charter of Athens. Their premise was that the essential elements of urbanism were “the sky, trees, steel and concrete, in that order and that hierarchy.”46 That same year, Le Corbusier completed an apartment building near the outskirts of Paris that exemplified this philosophy. The seven-story structure at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli had floor-to-ceiling double-glazed windows front and back, so that light from both east and west flooded into apartments that spanned the entire building.

Aboard the Patris II, on his way to CIAM IV in Athens, 1933

24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli, 1933

The tradition in Paris apartment buildings was to put the servants in small rooms under the roof. Le Corbusier knew these spaces better than most people, since his first Paris office and apartment, as well as the apartment in which he still lived, were initially maids’ rooms of this type. On the rue Nungesser-et-Coli, he wanted to “free the servants from the frequently dreadful subjection of their rooms under the mansard roofs.” He therefore put the servants’ rooms on the ground floor and basement level, with the ones in the basement facing a courtyard that received ample sunlight. It was not, however, only the servants whose needs Le Corbusier was considering. The unusual distribution of space left the roof free for “the best-situated apartment in the whole house: instead of slates: lawns, flowers, bushes.”47

Shortly after its construction, that duplex penthouse was reproduced in the latest volume of The Complete Work. The dwelling is shown to have a handsome modern dining room with large sliding glass doors that open onto a terrace with lovely plants and a garden chair. It also has an unusually high and austere platform bed on tall and lean stovepipe legs and several large paintings by Léger, as well as one by Le Corbusier himself. There is a cavernous studio with a brick wall and an efficient, shipshape kitchen in which a shapely dark-haired woman, wearing a blouse with wide ruffled lapels and short sleeves, is on view taking something out of a cabinet; she is the model of domestic perfection.

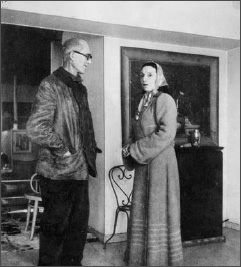

In another shot that presents the boldly geometric streamlined fireplace and the wide-open space of the living and dining areas, the same woman appears, this time from behind, on the balcony; now she is accompanied by a man, also seen from behind, in a robe. They look like the perfect urban couple from a film of the period: elegantly at home, happy together, impeccably dressed in their chic surroundings. What the photo captions fail to mention is that the woman is Yvonne and the man Le Corbusier himself. At the end of April 1934, they had moved from the rue Jacob to this penthouse.

14

It had not been an easy transition. Le Corbusier had found it hard to pack up and organize all of the papers he had accumulated over seventeen years. Yvonne was unhappy to give up St. Germain-des-Prés and leave the neighborhood where she knew the shopkeepers and could walk to her favorite cafés. For Le Corbusier, the vast amounts of space, the vistas, and the satisfaction of living in one of his own designs were worth the inconveniences. For her, it was Siberia.

Of course, there were some compensating amenities. They were again on the seventh floor, only now they could reach it by a small elevator. The duplex apartment was large and airy, and every last niche had been thought out carefully. Hinged walls that served as both doors and closets, and built-in shelves and cupboards were positioned ingeniously. The clean geometry of the straightforward plan, the bold planes of the floors and ceilings, and the lively staircase made the apartment a place of refreshment amid the complexity of Parisian life.

The textures of the apartment provided interesting juxtapositions: wood and plaster, marble and cane. The presence of water was also unusually strong. The bathroom, rather than being separated by a door, was open to the bedroom, with the bidet conspicuous as a piece of bedroom furniture. The sink was also in plain sight. Le Corbusier did not conceal the scenes of everyday ablutions in the usual manner of western designers; nor did he hide the water pipes. This most urbane of men never wanted to lose touch with the raw and vital elements of nature (see color plate 14).

Le Corbusier and Yvonne at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli, ca. 1935

The apartment gave Le Corbusier a superb studio, two stories high, full of daylight. With its curved ceiling and rough brick wall, that studio had aspects of the barn to which, in his youth, he had so happily retreated on the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds. It was like being in the country in the city, and it made painting the central act of his life at home. If now the office that was formerly a ten-minute walk away required about an hour’s travel time, whether by taxi or Métro, he did not mind. Le Corbusier would live at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli for the rest of his life.

15

Le Corbusier traveled to Algiers regularly. One evening there, he went to the Casbah to sketch in the light provided by streetlamps. Shortly after midnight, he was returning to his hotel along the narrow, empty streets when he was attacked with an expert maneuver called “le coup du père François.”48 While the origins of its name remain uncertain, this ancient technique involves one assailant addressing the victim with a question while an accomplice strangles him from behind by pressing hard on the jugular vein or carotid artery.

Le Corbusier was left unconscious. An hour later, when he began to come to, he instinctively asked himself who he was. Once he grasped what had happened, he knew how exceptionally lucky he was not to have been killed. Fascinated by the proximity of death, he recorded his impressions: “The ambience—in the depths of my unconscious—seemed to me a sort of shimmering golden puddle. Experts say all that gold and all that light are characteristic of moments of passage from life to death.”49

Focused on death and danger following that attack, just before Le Corbusier and Yvonne moved to their new apartment, he wrote to the prefect of police to report a series of strange events that had occurred three doors down on the rue Jacob. At number 14, two renters had died of tuberculosis in 1927. In 1930, another resident had died of the same illness; so had a husband and wife in 1932. They had owned a boutique in the building, and now the wife of the new owner also had died from tuberculosis. All of them were hearty country people from the Auvergne. Since another couple was coming from the Auvergne, Le Corbusier alerted the prefect that they would die two years hence. The outcome of his prediction is unknown, but Le Corbusier had no doubt of his knowledge that a space could have a terminal impact on its inhabitants.

16

Winnaretta Eugénie Singer-Polignac, born in 1865—in a vast granite mansion called the Castle, overlooking the Hudson River in Yonkers, New York—was the twentieth of the twenty-four children of Isaac Merritt Singer, the tall, brawny, foulmouthed son of a German immigrant who, in 1850, had borrowed forty dollars to make a prototype for an improved sewing machine. He managed to get a patent, although it essentially copied someone else’s idea.

Singer had begun fathering children when, at age nineteen, he married a fifteen-year-old. Winnaretta’s beautiful mother, Isabelle Eugénie Boyer, half French and half English-Scottish, said to be Bartholdi’s model for the Statue of Liberty, was the fourth woman to give him progeny. In 1863, she was seven months pregnant when she married Singer—although two other women claimed to be his wife, one as Mrs. Singer and one as Mrs. Merritt—in his large Fifth Avenue town house.

At about age five, Winnaretta was alone in her room at Brown’s Hotel in London when it began to fill with smoke; the stranger who rushed in, threw her on his shoulders, and carried her to the street was Ivan Turgenev. She grew up in the English countryside in a hundred-room, four-story house called the Wigwam. Her father, whom she adored, died when she was ten years old, leaving her some nine hundred thousand dollars. For the rest of her life, she treated the anniversary of his death as a sacred day, saying she never recovered from her grief; sixty years later, she wrote, “the one thing I had, I lost then.”50

When Winnaretta’s mother remarried, they moved to Paris, and the girl became consumed by a passion for both art and music. Her stepfather had a title, but he also had a hunger for the Singer fortune. Winnaretta, at age twenty-one, decided to take her inheritance in her own hands and have it managed by Rothschild’s bank. She began to indulge her own interests, buying a bold Manet from the artist’s widow and a Monet from the painter himself.

At age twenty-three, the sewing-machine heiress acquired a large mansion not far from the Trocadéro. She married Prince Louis-Vilfred de Scey-Montbéliard, an aristocrat passionate for the hunt, at a ceremony from which her mother and greedy stepfather were conspicuously absent. On her wedding night, she stood on a wardrobe and threatened her husband with an umbrella, saying she would kill him if he touched her. That marriage was annulled, freeing her to marry, at age twenty-eight, someone who preferred his own sex as she preferred hers. The fifty-eight-year-old Prince Edmond de Polignac was a penurious composer who descended from a family high in the court of Louis XIV; the couple entertained creative geniuses like Jean Cocteau and were patrons of Gabriel Fauré and Diaghilev.

The prince didn’t live long, but the former Winnaretta Singer honored his memory by being a great supporter of modern music. She added Stravinsky to the list of beneficiaries of her largesse, and on May 17, 1917, she had been, like Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, in the audience at the Théâtre du Châtelet when the Ballets Russes performed Parade, the collaboration of Picasso, Cocteau, and Satie that had inspired Apollinaire to use the term “L’Esprit Nouveau.”

In 1921, after Marcel Proust encountered Winnaretta at a party in honor of the duke of Marlborough’s marriage to another rich American, he described her as “icy as a cold draft, looking the image of Dante.”51 One wonders what Le Corbusier thought when he met her five years later. He had, after all, sculpted a likeness of Dante when he was fifteen.

In 1926, when the Salvation Army set out to buy and restore a large building as a women’s dormitory, Winnaretta embraced the cause. One blustery winter night, she saw Salvation Army officers dispensing aid to a miserable group of society’s outcasts, and she was moved to action. The commissioner of the army, Albin Peyron, then asked her if she would contribute to an addition to the existing Palais du Peuple, which was to house up to 130 homeless people. Her reply was positive, but with strings attached. Having been an early subscriber to L’Esprit Nouveau, she was fascinated by the links Le Corbusier made between architecture and music. Additionally, Albert Jeanneret was a friend of her friend Fauré. The princess told Peyron she might indeed fund a substantial part of the construction costs of the new building, but only if she could replace the army’s chosen architect with Le Corbusier, who, in 1926, was working on a design for a villa for her in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

In June 1926, Le Corbusier went to the site of the Palais du Peuple and was deeply impressed by the work being done there. He wrote the princess that they might build a modest, stripped-down structure onto it, where he would orchestrate bold forms with impeccable proportions. He assured her the results would be magnificent.

The addition to the existing building was never constructed, but in 1929 the Salvation Army decided to create the Cité de Refuge, a shelter for up to six hundred people, at a cost of six million francs. Whereas most people whose money had American roots were substantially wiped out that year, the princess’s fortune, which depended on a Canadian trust and was managed in Paris, flourished, and she offered half that money, again with the stipulation that Le Corbusier be the architect.

On June 24, 1930, the heiress laid the foundation stone. Eventually, she had to add more than a million francs to her gift when Le Corbusier went over budget, but, when the building was inaugurated by the president of the republic, Albert Lebrun, on December 7, 1933, her name appeared only on a small plaque over the entrance door saying “Refuge Singer-Polignac.” This rich woman’s modesty and generosity impressed Le Corbusier immensely. Heart, intelligence, and tenacity combined were his ideal.

17

The structure that opened on December 7, 1933, to house the homeless and provide a way station for immigrants was, in its heyday, a monument to visual inventiveness, technological advances, and, above all else, human dignity.

In the past, triumphant symbols of arrival, like large porticos and grand staircases, had belonged mainly to buildings associated with vast wealth. They demonstrated power—whether of the church, a monarchy, a strong government, or a giant of mercantilism. Now a new form of architectural welcome lifted the spirits of people who felt estranged from such institutions. A cubicle-shaped portico tiled in bright colors, a bridge, a vast rotunda, and a shimmering expanse of glass sheathing and mosaic bricks greeted the ex-convicts, unwed mothers, and tramps who previously had taken shelter underneath the bridges of the Seine. The sparkling sequence of geometric forms gave hope and dignity.

Today, our urban homeless burrow their way into basement soup kitchens and sleep in shelters. They are downtrodden by the message that their lives merit nothing better than cheap construction standards and shoddy materials. But when the Cité de Refuge opened its doors, it elevated the spirits of all who entered. For a very different clientele than at his luxurious villas, Le Corbusier had again succeeded in positively transforming human feelings through the architectural environment.

LIKE THE MONASTERIES of Ema and Mount Athos, the Cité de Refuge was meant to provide all the necessities of life for a large group of people living collectively. The program for the new building called for places for the residents to sleep and eat, with public assembly spaces and a range of support services including kitchens and a laundry. The entire structure was to be airtight, with a climate-control system that purified the air as it heated or cooled it; this was among the first structures in France to be air-conditioned.

Facade of the Cité de Refuge, ca. 1933

To achieve all that was not easy; from start to finish, there were disputes revolving around building codes. Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier tried to bend laws, circumventing regulations concerning the height of the structure and the construction of the glass-and-steel curtain wall. The Cité de Refuge took longer and cost more than anticipated.

But when the pioneering structure for the homeless was inaugurated on that raw December day at the nadir of an international economic depression, many people’s spirits soared. In his signature bow tie, Le Corbusier beamed in the company of President Lebrun, the minister of public health, and other government officials and dignitaries. Harsh criticism was expected for a building that violated tradition so audaciously, but there were those who instantly grasped its fresh and optimistic spirit.

The day following the opening, an anonymous journalist in Les Temps wrote that the “architects, Messrs. Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, whose fecund originality we already know, have given the edifice the appearance of a beautiful ship, where everything is clean, comfortable, useful, and gay.” The critic recognized the transformative powers of architecture, saying that at the entrance counter “unhappy people will come to deposit their misery like the rich deposit their valuables at the windows in a bank.”52

18

The dormitories of the Cité de Refuge filled up quickly. Soup was soon being ladled out free of charge. But not everything was as it was meant to be. The climate-control system, so radical in concept and execution, was a problem. Residents claimed to be suffocating from their inability to open windows at night when the ventilators were turned off. A doctor complained of treating children deprived of adequate oxygen. The temperature inside reached thirty-three degrees Celsius.

An intractable Le Corbusier refused to perforate the glass curtain wall with windows. He summoned Gustave Lyon, the expert who had, among other things, installed the air-conditioning at the Salle Pleyel, and Dr. Jules Renault, an authority on child care, to the site, and they both issued reports disputing the claims that necessary ultraviolet rays were failing to reach the children through the airtight membrane. Le Corbusier claimed the problems could be remedied by adjustments to malfunctioning machinery. But in January 1935, the Seine Prefecture condemned the Cité de Refuge for code violations, and the police ordered the installation of sliding windows within forty-five days.

Le Corbusier was desperate not to comply. He managed to get government officials to give some time to the engineers he employed to find another solution. Then Le Corbusier proposed drilling tiny holes in the glass wall, saying that the holes could be covered in the winter. But by the end of the year, he was forced to put in the new windows.

The problems did not stop there. By 1936, tiles had begun to fall off the rotunda. Children were deemed at risk of being injured when they went out to play. The tiles had been applied with mortar directly to the reinforced concrete, a method that failed in extreme heat. The architects and contractors together had to pay for half of the cost of repairs.

Le Corbusier never accepted blame for any of these problems. “The City of Refuge is not a fantasy; the city of refuge is a proof,” he declared. Its users “make a fuss and argue in perpetual confusion between their psychological reactions and their physiological reaction. They don’t know at all what they’re talking about; they are obsessed by fixed ideas and it is this obsession that is the cause of their protests. We have the obligation to ignore this and to pursue positive and scientific work with serenity.”53 The words were almost identical to his retorts whenever his mother criticized him for the leaks at La Petite Maison.

OVER THE YEARS following its construction, the concrete at the Cité de Refuge developed numerous cracks. Windows broke, paint peeled. But not all of the damage was the fault of the design. On August 25, 1944, the last day of the liberation of Paris, the Germans dropped a bomb directly in front of the building, shattering all the remaining glass in the facade.

On one visit to the Cité de Refuge when repairs were being made shortly after the war, Le Corbusier was shocked to discover that his pure concrete columns in the interior had been papered with materials imitating wood and marble and that an ornate and garish mural had been painted over his wall of glass bricks. In 1948, he oversaw a complete restoration free of charge, with Pierre taking on the bulk of the details. Today, some elements reflect their original concept, but a lot has been altered. The current Cité de Refuge is a ghost of the original. The structure on the edge of the thirteenth arrondissement was ultimately rebuilt so disastrously that Le Corbusier later announced, “The building can no longer be thought of as architecture.”54 What was built optimistically still stands as a symbol of hope and genius but also of decay, disrespect, and failure.

19

In spite of its flaws, the Salvation Army building won Le Corbusier an invitation to receive a Legion of Honor. The day after the inauguration, on December 8, 1933, he wrote the faithful Frantz Jourdain his response.

You offer me, with a generosity of heart I find deeply touching, the red ribbon that consecrates so many efforts. Your entire life having been devoted to the struggle for what is good, you do not forget that others follow in your footsteps and, having arrived, yourself, at the pinnacle of honors, you turn your solicitude toward them as a spiritual father. I hope my response to your offer will not be taken as that of a naughty boy, nor as that of an embittered man, nor as that of some sort of nihilist. Yet I must tell you that my attitude in life has always been a matter of a fierce liberty, and that at the present time, when good and evil are confused in a dangerous mixture, I owe it to myself—and to those who on all sides have acknowledged my efforts as a useful direction—to keep apart from all such consecrations and to remain the man of my idea: a man still at the beginning of his investigations.

I have twice already refused the Legion of Honor. On the occasion of the L’Esprit Nouveau; and then on the occasion of the Palace of the League of Nations. That time, scandalously enough, it was Lemaresquier who offered it to me: an exchange, a bargain!

Today, my dear friend, the atmosphere is different. You have made a gesture of friendship and esteem. Such is my reward! Remember that in 1922 I was without resources and you allowed me to produce the panorama of the “Contemporary City.” Eleven years later you consider that I have deserved further support. Here is another reward. I receive this consecration from you with a deep satisfaction and with a certain pride. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. And let this consecration remain between us without ribbon or a certificate. That way I am happy and satisfied. In the present state of my existence, the author of “The Twilight of the Academies” can no longer accept the Legion of Honor. This is a simple and direct decision, between the two of us. It is not a manifesto; it is an inner manifestation of my own state of mind—nothing more.

Here in Paris, and in Moscow as well, L’Humanité accuses me of being vulgar bourgeois. Le Figaro and Hitler denounce me as a Bolshevist. I am and desire to remain an architect and an urbanist with all the consequences which that may involve.

And I desire above all to remain in possession of your esteem, quite simply, as before, by the effect of my efforts which I seek to pursue in all simplicity and strength.55

Eight days later, he wrote Anatole de Monzie, the minister of education:

Maître Frantz Jourdain has made (he tells me) a formal request for me to be awarded the ribbon of the Legion of Honor.

It is with some embarrassment that I must reject this disinterested initiative, for it is my desire not to receive the Legion of Honor. I have informed Frantz Jourdain of the fact, but he seems not to understand me.

You will greatly oblige me by willingly acceding to my desire and above all by being willing not to consider my gesture as a pretentious manifestation. On the contrary, what is involved here is an attitude dictated by an inward, entirely individual state of consciousness, one exclusive of all publicity. My entire life being devoted to an effort which finds the academies constantly in its path, I have no choice but to remain apart from a distinction that would oblige me to enter the rank of certain people with whom I am in acute disagreement.56

20

As Le Corbusier was building, the world was moving in horrific directions. By October 1934, the writer Carl von Ossietsky had been in concentration camps for twenty months. He had been incarcerated the day following the burning of the Reichstag and imprisoned in Sonnerburg and Esterwegen. A committee was formed to protest this act. Von Ossietsky’s main offense seems to have been that, as a newspaper editor in Berlin, he had protested the budget of the Third Reich. Among those who joined the committee and signed the letter of protest were Thomas Mann and Le Corbusier.

Still, Le Corbusier had no clear ideology or political stance. In this same period, through Pierre Winter, his new neighbor on the rue Nungesser-et-Coli, he grew close to the fascist organization Le Faisceau. Winter wrote newspaper articles extolling the merits of Le Corbusier’s housing and stated that Pessac was a concept well suited for the ideal fascist state.

Philippe Lamour, the lawyer who had represented the architect with the League of Nations, joined Winter in forming the Parti Fasciste Révolutionnaire; Mussolini was one of their heroes. Le Corbusier worked with Lamour on several publications and even tried to have Lamour’s new magazine take over L’Esprit Nouveau. Le Corbusier remained friendly with Lamour throughout the next decade—apparently unbothered by Lamour having gone to Germany in 1931 with Otto Abetz, a head of the paramilitary organization Reichbanners, to create a German cell of the Front Unique.

Le Corbusier was similarly unfazed by the rise of fascism in Italy. Adriano Olivetti, the director general of the typewriter company that bore his name and another of those rare businessmen whom Le Corbusier admired as a form of modern hero, was an irresistible lure. Olivetti invited Le Corbusier to come to his offices near Turin to discuss issues of urbanism, and Le Corbusier engaged in a series of projects for Olivetti, although none of them were completed. Italy was welcoming; in 1934, the architect gave lectures in Venice at the Palazzo Ducale and began negotiations in Turin about a factory for Fiat. He imagined that the country of his early inspiration would become the land of his support—so much so that, by the end of the decade, he happily anticipated that one of his backers would be Benito Mussolini.

Yet Le Corbusier could join forces against Il Duce as readily as he would work for him. In 1933, the architect and Pierre Winter, François de Pierrefeu, and Hubert Lagardelle created two reviews: Prélude and L’Homme Réel. The agendas of the publications were unclear, but the heroes included Nietzsche and Gandhi, and their editorial pages protested Mussolini and fought fascism, while supporting Spanish anarchists and republicans. When Le Corbusier had written his mother and Hélène de Mandrot that he had faith in no one political system, he had been telling the truth; he would support or oppose almost anyone or anything, since the sole issue that counted was who would let him promulgate his ideas and build.