XXXIII

1

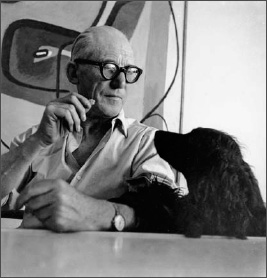

After returning from America, Le Corbusier retreated to the privacy and comfort of his studio; it was his usual formula of immersing himself in the luxury of creativity on the most intimate scale whenever he despaired of his ability to change the entire world. Paintbrush in hand, a canvas in front of him, his wife just a room away, the aromas of garlic and tomatoes simmering in olive oil wafting from the kitchen, their dog scurrying around the apartment, he was content.

The moment, however, that he was beckoned to make large-scale architecture, with a chance of designing cities as part of the package, he jumped. The Brazilian government asked Le Corbusier to help develop plans for headquarters for both the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Public Health. In July 1936, he returned to Rio.

At 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli, ca. 1935

Sketches comparing the structure of a fir tree and a brise-soleil on a skyscraper, early 1940s

Le Corbusier made the trip on board the Graf Zeppelin, a dirigible airship filled with hydrogen that took four days to go from France to Brazil. He was thrilled by the custom-fitted interior of the unusual vessel, its mechanics, and the hoopla when it landed—all the Brazilian natives rushing about to anchor the great airship.

His mood plunged when he saw the site chosen for the Ministry of Education. Then he and his clients found a more suitable setting for which he designed a vertical slab with end walls made from the local pink granite. His spirits soared, even when the minister of education told him that the plan would not work: one of the main facades faced north and would heat up intolerably in the sunlight. Le Corbusier was elated rather than discouraged by what might have been a hurdle. He had a breakthrough idea: he would use brises-soleil.

He had initially developed brises-soleil for his studio at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli and had then proposed their use in some of his designs for Algiers. These “sun shields” were further inventions through which Le Corbusier intended to change the way people lived and worked. The idea was to use horizontal slats to protect windows from direct sunlight. Le Corbusier believed that by observing the movement of the sun in the course of an entire year, one could fix these brises-soleil at the correct angle so that during the summer there would never be direct sunlight on the windowpanes, while in the winter, when it was desirable, there would be. Deferring to the ruling power of the sun, they accommodated the need for living conditions that are neither too hot nor too cold. The project in Rio would allow him to employ these splendid devices on an unprecedented scale.

TODAY THE RIO building is smaller than many structures around it, but it radiates a power they lack. The slab on tall pilotis manages the Corbusean feat of being dense and graceful at the same time. Its solid side walls have fantastic presence. But the brises-soleil that cover the larger northern exposure are not as Le Corbusier intended. Whereas he would have preferred all the elements neatly aligned with one another, they were immediately adjusted to various angles according to the wishes of the inhabitants of individual offices. Their differing positions give the building a haphazard look.

With his device purportedly designed to benefit a large group of people with a range of needs and tasks, did Le Corbusier truly care about their comfort above all? Or did his ability to impose an aesthetic standard, to dictate someone else’s way of life and maintain authority regardless of the actual experience of his beneficiaries, matter more than anything else? The architect had himself convinced he was serving humankind; his effectiveness was debatable.

2

While in Rio, Le Corbusier was asked to design a university campus, which would include a law school, medical school, hospital, museum, sports stadium, restaurants, clubs, housing, liberal-arts departments, and other facilities. Government regulations forbade his receiving a fee for the project, but the local authorities found a loophole. They asked the architect to give six lectures, for which he was paid substantial stipends that compensated him for the design work. At those lectures, the architect proposed one of his most radical urban schemes. To counteract what he declared to be the “horrifying chaos” created by the rapid and random development of the nineteenth century—where “everything here is false, frightful, cruel, ugly, stupid, inhuman”—he designed a unifying scheme for all of Rio that honored its specific geographical situation.1

A second city was to be built on top of the existing one. Le Corbusier’s proposal resembles a gigantic elevated ribbon snaking among the hilltops that flank the Brazilian metropolis. The undulating slab would sit on top of pilotis 120 feet high. In one direction, it faced the bay—the shape of which is echoed by the serpentine lines of the slab. In the other, this continuous line of buildings looked toward the mountains. On top of the slab, there was a divided motorway. It was one of Le Corbusier’s most daring and imaginative schemes—however unrealizable.

IN RIO, he became aware that six months had elapsed since he had seen Marguerite Tjader Harris. Being back in Brazil also brought on memories of Josephine Baker.

Le Corbusier wrote Tjader Harris, opening the letter, “I no longer understand how I could sleep with black women. There are crowds of them here, some very beautiful. So much the worse.”2 Over the years, his need to tell this one woman about the others became chronic. She tolerated Le Corbusier’s disregard for the effect of his confessions.

Having last been with Tjader Harris shortly before he set sail from New York, he now told her, with meticulous recall, “I haven’t made love since December 13. Ridiculous. Especially ridiculous to note the fact and to assume it means something. We spoil everything with these observations of minor circumstances which are quite inexplicable. Except for arithmetic, nothing can be explained. We paddle in incomprehensible seas…. Lacking yours, I have these. But here we must wear bathing-suits. And a simple piece of wool is a nasty privation of great delights.”3

Le Corbusier had recently begun to write When the Cathedrals Were White. He told his mistress that he could not have written it without her, and his underlying idea was that she should translate it. This was when he subtitled the travel journal In the Land of the Timid. These “timid” Americans, he added, were “hefty” but purposeless: “they still don’t know what to do with their strength in order to have something in life to show for it.”4

Le Corbusier had recently had his palm read and been told 1936 would be a year when he could take risks. The numbers concurred. He was forty-eight; four plus eight equaled twelve, two plus one (the digits in twelve) equaled three, and three times twelve was thirty-six. These figures all represented harmony. They gave him the reassurance and balance that, he told Tjader Harris, permitted him to face squarely the anguish of his American trip, which seemed even more disastrous in retrospect.

In contrast to New York, Rio was a virtual paradise. Even in winter, there was sunshine; the sky was perpetually blue. He swam regularly in the middle of the day, and everything was a feast for the eyes: the men who dressed in white, the “roads of love” where hundreds upon hundreds of women walked hand in hand. Le Corbusier elaborated on those roads, where prostitutes welcomed their clients: “Before 1930 the whorehouses faced the sea. The preference was for French women. Today a moralizing rigor is in force, which jars in this exuberant site.”5 He relished the liberty of reporting it all to his aristocratic, Catholic, American mistress.

ONCE HE GOT BACK to Paris, Le Corbusier received word that neither his urban plan nor most of the other ideas he had proposed for the Brazilian capital were wanted.

He was becoming increasingly skeptical, and realistic, about his ability to inspire a universal revolution. In November 1937, when his friend Elie Faure, an art historian who specialized in antiquity, died, Le Corbusier reflected, “He had to die before his work could be revealed to the public and his views circulated. Now people are looking at his texts. Tomorrow will show that he was clairvoyant. Death is the sacrament of life.”6 For the rest of his life, he assumed that he and his work would be better appreciated once he, too, was no longer alive.

3

At least the pavilion Le Corbusier was building for the international exposition to be held in Paris near the Porte Maillot later that year was a reality. It was not a master plan for Rio or a city in America, but it would actually happen.

The architect had been making proposals for the exposition ever since it had been conceived in 1932. Initially, he recommended that instead of being called “The International Exhibition of Art and Techniques” it become the “International Exhibition of Housing.” Housing, he decreed, was the essential issue confronting civilization. His megalomaniacal attempt to dictate the overall theme of the exposition fell on deaf ears, however, and he later publicly complained that his thirty-six printed pages of suggestions “did not even get a formal acknowledgment.”7 Between 1932 and 1936, he had drawn up three different schemes for his pavilion—all of which had been rejected. But just after the exposition had opened, the French prime minister, Léon Blum, had been dismayed to discover that Le Corbusier’s proposals had been turned down, and in December 1936, four months after the opening, Le Corbusier was offered the funds to build. The architect at first went into a public sulk and said “it was too late.”8 But having a prime minister take his side was irresistible. Le Corbusier reversed himself and agreed to erect a structure devoted primarily to the themes of town planning and Paris.

While the pavilion was being built, few people knew that, as was so often the case, Le Corbusier was afflicted by health problems. For about three weeks in April, he suffered from symptoms that suggest a flu or sinus infection or combination of the two. No specific diagnosis was given, but the architect was laid flat by headaches, congestion, and malaise. After a specialist assured him that he had no major health issue beyond the visual impairment that was a given, he became delighted with the enforced stop in his life. Yvonne took such good care of him in the new apartment that he wrote to his mother that the twenty days of illness seemed to fly. Bedridden, he had a wonderful view of the sky, and he was perpetually cheered by the optimism of André Bauchant’s paintings. He could not really be all that sick, he reassured Marie, because he was well enough to smoke—news he assumed would relieve her enormously.

It was one of those moments when optimism and a sense of celebration permeated Le Corbusier’s psyche as surely as pessimism and regret catapulted him downward on other occasions. Positioned with great vistas from his apartment yet with the city center in reach, he believed the reason he could feel so well while being ill signified the “victory of the Radiant City!”9 Besides, he was building his pavilion and being accorded respect from both the fringes and the mainstream. In his penthouse on the outskirts of Paris, he imbibed life’s bounty.

THE FRENCH COMMUNIST PARTY was organizing a conference to take place that July to address the theme of the international exposition, and the honorary committee—which included Louis Aragon, André Gide, and André Malraux—asked Le Corbusier to be one of the main speakers. When, two weeks after he spoke under those auspices, the Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux opened, the architect was finally decorated with a Legion of Honor. Having turned down the medal on four previous occasions, this time he accepted it in order to rebut recent attacks in which he had been declared anti-French.

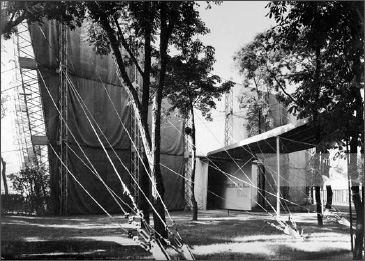

Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux at the International Exposition in Paris, 1937, entrance facade

His new pavilion was true to the determination of the French Communist Party to challenge and confront the old ways of doing things. Le Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux was a fifteen-thousand-square-meter space with walls and a roof made of cloth that was boldly colored in yellow, blue, red, and green. Its structure depended on tensile vertical pylons, similar to poles used to support high-voltage power lines, and on steel cables that anchored it to the ground. The temporary structure looked like a building under construction more than one that was completed. To modern eyes, it resembles a wrapped structure by the artist Christo, in particular his Reichstag encased in paper and string, as if it were a gigantic package.

Inside the pavilion, an airplane was suspended from the roof. Murals and dioramas by Le Corbusier and José Luis Sert evoked modern industry and the latest advances in technology. Le Corbusier told his mother that his intention was to create “an event, something strong, commanding, healthy, convincing. A battlefield, it goes without saying.”10

Without some struggle, after all, how could he triumph? Le Corbusier publicly whined that “no bigwigs came to open it,” but he viewed the lack of attention as directly connected to the brilliance of what he had done: “It was the boldest thing you can imagine.”11

4

Le Corbusier showed his latest plan for Paris in the 1937 exposition. It left the French capital’s monuments and city center intact but added four large skyscrapers lined up in a row on the outskirts. The magazine ART, referring to the eighteenth-century architect whose exaggerated classicism was a symbol of the ancien régime, called this proposal “a megalomania worse than Ledoux’s, a vandalism unique in history, the dreary uniformity, vanity, and monotony of these skyscrapers…have been proved morally and spiritually injurious, a contempt for historic and artistic tradition.”12 Le Corbusier quoted the diatribe in My Work; the more pulverizing the critique, the more he reveled in it.

That year, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret also designed a stadium and open-air theatre for one hundred thousand people. At the time, it was mocked—Balthus and Picasso, both of whom preferred grand French buildings, compared the stadium to a gigantic saucer missing its cup—although twenty years later the Iraqi government commissioned a sports center for Baghdad along very similar lines.13

Le Corbusier’s design for a monument at one of the main entrances to Paris, made for a competition organized by the Front Populaire, was, Le Corbusier himself explained, “rejected with a certain amount of nastiness. The most advanced artists, friends of Le Corbusier, castigated him for putting forward such a proposal.”14

With all these defeats, the architect’s fiftieth birthday hit him hard. To Marguerite Tjader Harris, he wrote that the official honors had been abundant, “but hatreds abound, and the struggle is as harsh as ever. For the time being, total ‘depression,’ no work.”15 Le Corbusier told her that an astrologist in Rio—not the same person as the palm reader—had said that at age fifty he would join the sun, Jupiter, and Venus in the most beautiful sky possible. Nothing of the sort had happened; no one in New York or Paris or Algiers was building Corbusean cities, and he felt deserted. And while he was stagnating, the bourgeoisie, the academics, and the lazy traditionalists were all thriving.

In early December, Le Corbusier and Marguerite Tjader Harris managed to organize a couple of nights together at the Hotel de la Cloche in Dijon. Afterward, he wrote her, quoting his friend Maurice Raynal as having said, “Behind that stiff facade, Le Corbusier is a tender-hearted man” he asked her to confirm that this was so.16 He then leaped from the issues of human personalities to the personalities of cities. He complained that Zurich, like everything in Switzerland, was “intimate” he preferred grandeur. London had now become one of his favorite places; it was “sumptuous.” “This black city” offered a panoply of rich experiences, from the traditional clubs in their dignified nineteenth-century buildings imitative of the Medicis’ palaces to the beautiful merchandise in the shops, especially the woolens and leather goods.17 On a recent visit to the British capital, its strong and powerful life struck him as ripe for romance.

He boasted unabashedly to his American mistress about a conquest: “Then a party at some gentleman’s house. I had noticed the loveliest woman there. And as fate would have it…. In three rounds, as boxers say.”18 He was telling her this only a month after their escapade together in Dijon.

THEN THE ANSCHLUSS occurred. With Hitler’s invasion of Austria, the devaluation of the franc, and the failure of the Front Populaire, human civilization seemed threatened as never before.

Le Corbusier saw both tragedy and possibility in all the changes: “March 18, 1938: Disappointing days. Imbecility everywhere, arrogance or funk. Dilemma. Terrible risks of a nameless war. Behind all this: nothing! Words, ghosts, and even so, there are the haves, unwilling to accept even the possibility of a new world. They’d rather die on top of their gold. But they will make everyone else die of impotent rage. At least such terrible death agonies will be the end of the disease, the birth of a new civilization, and there will be more to talk about than chimerical vanities. What I mean is, people will share, will start afresh, will group together! We must wait and see!”19

In June, a Paris-based organization devoted to helping partisans wounded in republican Spain asked Le Corbusier to issue a statement. He complied by calling the fighting in Spain “satanic madness.”

Under the pretexts of points of view, blood runs, and men’s bones are broken….

What immense and total gratitude we have for those doomed to this hell. We must sustain them with our most active love.20

Later that year, Le Corbusier asserted that the signers of the Munich accord, most especially the British prime minister, symbolized human evil: “Chamberlain seems to me the most dangerous kind of grim reactionary: the City, profits, money!” The invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 made him even more miserable: “Then the Jews treated as no one ever dared imagine.”21

How long he would sustain the victims of fascism with his “active love” remained to be seen.

5

In 1938, a major exhibition opened at the Kunsthaus in Zurich presenting almost all of Le Corbusier’s paintings of the past two decades.

Since the inception of Purism, his painting style had evolved significantly. His still lifes had become increasingly complex, containing myriad elements in lively, animated relationships. He had also taken to making bold, oversized figures—similar to Léger’s but even more broad shouldered and muscular. The effects of Braque and Picasso could also be seen in the ways human form, machine parts, and musical instruments were combined.

Like his spoken and written language, his painting style is animated by a high energy level, a deliberate complexity, and an urgent charge. But also like his verbal communication, it occasionally lacks clarity, as if emotional tumult is more honest and valuable than self-editing.

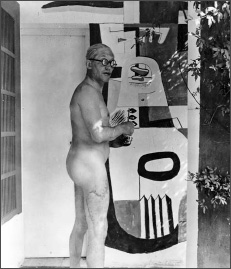

In his studio at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli, late 1930s

When the show opened, there was no press coverage, and his friends remained silent—with just one exception. Le Corbusier’s old pal and banker de Montmollin sent him ten bottles of Neuchâtel wine to celebrate the event—a gesture the architect would never forget. For it was a bittersweet experience. Le Corbusier wrote of his Zurich exhibition, “I couldn’t have been rejected more completely. At least I’ve shown myself for what I am: a competent technologist, pursuing the harmonious path: poetic creation, the sources of happiness.”22 Rejection had had two effects: to show him who his real friends were and to reinforce his belief in his own achievement.

6

Le Corbusier had first overlapped with the stylish and aristocratic Anglo-Irish architect and designer Eileen Gray at the 1922 Salon d’Automne, where he presented his Citrohan house. Gray, nine years his senior, had exhibited an inventive black lacquer screen, as well as other furniture and textiles. These highly original forays in pure and vibrant geometric abstraction had made Gray’s name one that everyone knew.

Two years later, Le Corbusier’s friend Jean Badovici, an architect and editor, asked Gray to design a house for him in the region of Saint-Tropez. Looking for a suitable spot, Gray went far afield from the normal holiday haunts. The intrepid Irishwoman explored the wild and undiscovered reaches of the Riviera countryside on foot, with a donkey to carry her bags over the mountains. In the course of her search, she checked out a property completely inaccessible by car in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Having found an equivalent of the rough Irish coast, Gray was determined to build there. The natural setting was as daunting as it was beautiful: craggy, difficult to navigate, and full of precipitous drops.

Between 1926 and 1929, Gray built on that spot “E. 1027,” a handsome and streamlined villa closely related to Le Corbusier’s architecture of the time. Gray knew Le Corbusier’s work well from having visited Ozenfant’s studio and gone to Stuttgart for the Weissenhof Siedlung. The house Gray built had the identical vocabulary as Le Corbusier’s villas; while it had the imprint of Gray’s own design sense, it was clearly derivative. It was named E. 1027 to evoke Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici—the “E” was for “Eileen,” and the “10,” the “2,” and “7” for, respectively, “J,” “B,” and “G,” because of their positions in the alphabet.23

In the 1930s, when Le Corbusier and Yvonne were visiting her birthplace on one of their trips south, they stopped by E. 1027 for tea. Le Corbusier was astonished by the lush and rugged landscape sloping to the sea, similar in topography and dramatic beauty to Mount Athos. For all the south-of-France elegance of the general region, here one felt in direct connection with the forces of the universe, with the sea and sky as they had been for tens of thousands of years. Yvonne was delighted with the view of the coastline westward, where her native Monaco, at that time still a village, was in plain sight.

In 1938, Le Corbusier and Yvonne stayed at E. 1027 during the course of a summer holiday in Saint-Tropez. By this time, Gray, who had initially lived with Badovici, had moved out. Le Corbusier was disappointed that the fascinating Irishwoman was not there. He wrote her a fan letter about the house, applauding “the rare spirit which dictates all the organization inside and outside.”24 But for all the praise, Le Corbusier decided to improve on her design by painting murals there. Gray was not consulted.

Having become passionate about wall painting, Le Corbusier painted, both on that holiday and the following summer, eight enormous floor-to-ceiling frescoes—mostly of oversized naked figures cavorting sexually. One of the murals was on the previously spare white wall behind the living-room sofa, so that what had been specified by Gray to be a point of visual respite was now an animated scenario. In 1939, the architect was photographed working in the nude on these bacchanals.

Gray was outraged. Her biographer, Peter Adam, summed up her response: “It was a rape. A fellow architect, a man she admired, had without her consent defaced her design.”25 But the rest of his life, Le Corbusier would proudly reproduce the murals, pointing out only that he had painted them “free of charge for the owner of the villa.”26

Painting the exterior mural at the villa E. 1027, summer 1939. The scar was from a swimming accident.

7

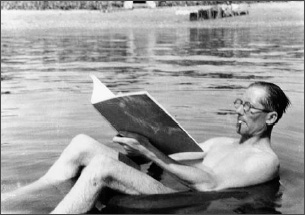

In Saint-Tropez, the architect took a long vigorous swim, sometimes two, every day in the warm waters of the Mediterranean. Shortly after the first escapade at E. 1027, Le Corbusier started a swim by diving into the water off the Môle Vert—the green breakwater. He headed toward the Môle Rouge—another jetty about 120 meters off. This was well within the range of his ability, even with the strong waves that day.

A powerful motor yacht was racing through the water. No one on board saw the swimmer stroking along, his broad shoulders and strong arms lifting rhythmically, his legs kicking in perfect sequence as he continued his daily exercise in a straight line created by the pronounced depression between two large waves. The fifty-year-old architect was about a quarter of the way toward his objective when he felt something hard hit his head. He discovered that he was under a boat. He noticed that it was as if the sunlight was trapped with him in a white and luminous cavity.

We know these graphic details because, more than a month later, Le Corbusier responded to a request from his mother for the most specific description possible of the accident he miraculously survived. In relating what happened, he diminished his own significance. He said that he rolled along “like paste out of a tube” under the keel of the boat. He went its entire distance, determining that it was between fifteen and eighteen meters. While being pushed along, Le Corbusier told himself to stay calm until he reached the stern, at which point the whole unfortunate affair would be over. However, instead of emerging easily from beneath the far end of the boat, he came smack up against rapidly moving propeller blades. As he told his mother, with deliberate understatement, “The motor at 200 horsepower—a good clip.”27

In Saint-Tropez bay, summer 1938

What occurred next was pure Le Corbusier. He completely suspended his emotional and physical reactions. Disconnected from his physical pain, he focused entirely on the behavior of other people—and attended logically to his immediate needs.

He reported to his mother, “After the first turn of the blades, I was thrown out of the circuit and seemed not to have been hurt. I reached the surface, and breathed air. I hadn’t swallowed a drop of water. I saw the boat gliding slowly away. I shouted: ‘Hey, wait a second, you went right over me, there may be some damage!’ Quite automatically my hand went to my right thigh, my arm fitting nicely inside. I looked down: a big area of blood-red water, and half my thigh floating like a ray (the fish!), attached by a narrow strip of flesh: ‘throw me a buoy, I’m badly hurt.’ The yacht headed toward me, throwing me a sort of rope knot too big to be held in one hand. The side of the yacht was too high for anyone to help me. ‘Throw a lifesaver.’ It comes, and I sit inside it. And here are some fishermen coming into port; their boat is low, they hold out their hands, and I give them my left hand, because I’m holding my thigh together with my right; we reach the place I started from, on the breakwater; I get up on the jetty; a kind driver appears out of nowhere and helps me sit down beside him. The fisherman gets in the backseat. Hospital. They put me on the table and begin sewing me together. This lasts from six to midnight, in two sessions. I’ve already told you the rest.”28

For all his mental detachment, he had recognized the imperatives of staying alive.

REPORTING THESE EVENTS through an architect’s lens, Le Corbusier emphasized the factor of scale. When the people on the yacht threw out the rope with a large knot, what mattered was that the knot was too large to be held by a human hand. Then the side of the boat was too high for anyone to be able to help. Le Corbusier had had the presence of mind to recognize that he therefore needed a lifesaver and to call out for one to be thrown to him. A command of tools and a knowledge of mechanics had enabled him to survive.

Once Le Corbusier was seated inside the circular buoy, the event became more like a biblical parable. The yacht and its wealthy owners were too far above the roiling sea to help, but because the modest fishermen had a boat that was closer to the surface of the water—a vessel of work rather than pleasure, more connected to the ocean than separate from it—they provided salvation. Rather than risk trying to get the nearly dismembered Le Corbusier into their small boat, they pulled him along and brought him back to the breakwater. The heroes of the story were anonymous: the sympathetic person with a car who rushed to the scene and helped place Le Corbusier in the passenger seat next to him, and the fisherman who rescued him.

Le Corbusier later wrote Marguerite Tjader Harris that he had been “cut to pieces” during the two surgical procedures.29 He was in the local hospital for four weeks in all. He calculated that he had two meters of stitches—a statistic he often announced—plus a hole in his head.

There was another detail he recounted to his mother as well: “On the green jetty I said to the bystanders: ‘Hand me my glasses and my clothes.’”30 He had not for a moment lost his rationalism.

8

Shortly after the accident, Le Corbusier went into the sort of rage that overtook him when he felt others had inflicted unnecessary suffering on his mother. He was more upset by the way Marie Jeanneret heard about his encounter with the propeller blades than by the event itself. For this he blamed journalists. Paris-Soir and other papers had picked up the story about the famous architect and reported it immediately. He was furious that the newspapers’ greed for gossip had resulted in his mother’s being far more frightened than if he had been the first to inform her—once he had returned to consciousness. The idea of Yvonne becoming involved in the communication seems not to have occurred to him.

And of course the papers were inaccurate. To alleviate the anxiety of his aged parent, Le Corbusier wrote her a letter from the hospital ten days after the surgery to specify the details the papers had gotten wrong, even if he had not succeeded in his goal of telling his mother first—and would have to write a second letter nearly a month later in response to her request for more precision in his report. The person for whom architectural rejection was tantamount to tragedy presented a life-endangering accident as a miracle of good fortune. He also made clear that his concern was for his wife and his mother as much as for himself.

Hospital, Tuesday August 23 ’38

Dear Maman,

Yvonne and I sent you a note the other day at Evolème. Did you get it? I was afraid that the papers would have printed the story and that my accident would be revealed to you by some third party. Wretched Paris-Soir actually reported the whole thing….

I’ll try to put the whole thing on a strictly factual basis:

1. Ten days ago I was sliced up by a yacht propeller.

2. There were several ways of being killed or hideously crippled; and one way of escaping; slick as a lizard. The miracle occurred: I’m calling it the miracle of Saint-Tropez.

3. The head was the object of a special operation, in the presence of Prof. Démarets, one of the glories of Parisian medicine. It could have been serious. Nothing of the kind. Better still, it’s all over today, healed, liquidated.

Thigh. Yes, the famous lardaceous tissue. But the propeller cut lengthwise and not across: no vein or artery touched. The wound is the size of the Radiant City (the book). Today is the tenth day. I don’t have even one degree of fever. Baths the last four days, and the Carrel-Dakin solution has had its effect. The wound is clean, ready to be sewn up. Here, 1 doctor + 1 surgeon to deal with it. Tough customers who inspire every confidence. The hospital personnel extremely attentive and kind. Bravo, hospital, the only place to go when you’re sick. This business has given me the reputation of being extremely brave. From six in the evening to midnight on Saturday the 13, I was cut, sewn, mutilated by the medicos without being put under. The doctor complimented me.

And now everything is put right. I hope to leave the hospital at the end of this week. This monastic retreat has not been without interest for me. High moments of resuming contact with the truth of things.

Yvonne of course was terribly shaken. She’s with good friends who love her and are taking care of her.

So now you are well-informed. Take it in with all the serenity of your alpine vacation.

All my affections31

The Carrel-Dakin solution to which Le Corbusier referred was a system of irrigation for infected wounds using an antiseptic solution containing sodium hypochlorite. Le Corbusier had no idea that in little time the French surgeon Alexis Carrel, who had developed it with the English chemist Henry Drysdale Dakin, would become a close colleague.

BEDRIDDEN IN the Saint-Tropez recovery unit and unable to move virtually any part of his body while he recuperated, the architect became preoccupied with Juliana, one of his nurses. Her little acts of kindness impressed him deeply, especially as he learned Juliana’s life story and became keenly aware that she was an unlucky and grief-stricken woman. Her hardships made her generosity of spirit all the more remarkable.

The Provençale nurse was the first person every morning to smile at people suffering from illness, gracing the lives of all the patients, massaging the muscles of paralytics. She always brought Le Corbusier garden flowers in a glass and placed them on his bedside table. The architect became convinced that an underpaid hospital employee who acted in this way exemplified pure charity. “Each morning’s smile is an eloquent object,” he wrote.32 The commentary on Juliana’s ability to give joy was both an expression of his priorities and advice to his mother.

9

Marie Jeanneret was deeply upset by all these events but full of admiration for her son’s fortitude. The encounter with the yacht motor and his handling of it garnered him some of the praise he craved. On September 11, his mother wrote him,

Thanks be to God you’ve left the hospital and can benefit from the good salt air following the dreadful adventures from which you have emerged wounded and further weakened by weeks in bed and so much suffering. The suffering you never mentioned: now you can claim direct lineage with the famous Spartans in their heroic combats with pain….

My dear boy you are a hero; you never fought in a war but had you been in the ranks of the brave soldiers of ’14 to ’18, you would have been cited for honors, for you have even more character than they, and strong characters are rare….

All of which is not to boast too much about you, but just to acknowledge those who accept without a murmur and suffer without complaint.33

She continued, “Make fun of your old lyrical Maman! There has been no lack of bad moments lately, and so we must praise those who warm our hearts.”34 She understood his admiration for Juliana; she also shared her son’s insistence on facts and clarity: “Now before ending, I’d like to ask one more favor of you. Couldn’t you tell me in detail how the yacht accident actually occurred? How you were found (fainting etc.), how the rescue was effected, things about which we are far from being informed.”35

Meanwhile, in her suffering, Albert, she assured Edouard, was her “compagnon fidèle.” If she meant this to comfort him, it surely had the opposite effect.

BY THE END of the third week of September, Le Corbusier could put on his pants and shoes by himself and had given up his cane. His skin still pulled when he walked, but after more than a month of being immobilized, he was on the mend and in high spirits.

Shortly thereafter, Marie and Albert wrote jointly to Edouard. Now that he had provided the full report as requested, they replied, “Lately your description of the accident gave us all the shudders, and we have thanked God for sparing you. He will preserve you for a still higher task.” Le Corbusier’s brother added, “The moving account of your accident almost made me faint, but Maman’s solid temperament saw her through. Certainly it reads like a page describing the heroes of long ago, whose character is not likely to be found in our period, in the tranquil ambience of present-day life…perhaps an ambience quite out of date.”36

It had taken happenstance, not architecture, to get that admiration at last.

10

After writing Edouard about his accident, Le Corbusier’s mother continued, “We need all our strength for future storms, for the Inevitable approaching with giant strides. Can it be possible, O Lord, that by the frenzy of one man an entire continent is being swept into the abyss? I listened to Hitler’s speech in Berlin, and since then I cannot believe that so many appeals to humanity and wisdom from so many quarters will be heard! It is abominable and terrifying! Everyone here agrees about assisting those in despair because politics has forced them to accept exile in other countries. But to seek out atrocity and to wield it in this fashion denotes a man who has turned into a barbarian, an hysterical madman, a dangerous mystic. I am overwhelmed by all this, and especially for your sake, in the fiery furnace as you are. What will you and Y and Albert and Lotti do in Paris if war is declared? You know that my little house is always open to you and that you would be safe here…. I say this because in your present condition, my son, you cannot assist in the defense of your new country.”37

Le Corbusier was not as worried as his mother. At the end of 1938, he wrote Marguerite Tjader Harris with the news that the plan for Algiers was moving ahead; finally, he would achieve his objectives there! Using military language—as if, like the armies of Europe, he, too, was waging war—he said that he believed that, after six years of perseverance on various fronts, he had at last conquered public opinion.

His only problem, he confessed to Tjader Harris, was Yvonne’s refusal to have sex. He complained that he was living like a monk; the situation with his wife was “harsh and terrible. My nights are filled with intense imaginings.” Tjader Harris, of all people, should understand how taxing abstinence was for him: “You know me well enough to know that this ascetic life I am leading is a heroic effort for me.” But he was determined to resist other temptations; “If I were to yield even slightly now, I should be a ruined man.”38

The year 1938 loomed in Le Corbusier’s thoughts as the “époque magnifique.”39 Tjader Harris thought so, too. From her large house in Darien, leading the life of a dutiful daughter and attentive mother, she wrote him delicately flirtatious letters. She regularly gave news of Toutou and her mother and asked warmly after Le Corbusier’s mother, but most of all she missed its being just the two of them. A friend of hers adored her Le Corbusier chair; nice as that was, she longed for the architect “by himself.”40

11

In March 1939, one of Le Corbusier’s best Spanish friends was killed by a bomb. The architect wrote his mother, “One must not let oneself be overwhelmed by death. It is the most natural event in life. If life has been even normally fulfilled, I do not see how death can come as a disruption.”41 He was devastated when Franco’s forces then took Madrid and Hitler invaded Poland—there would be fewer chances to make architecture when people could think only of defending what they already had rather than building anything new—but he was determined to hold the darkness at bay: “Better to occupy one’s life with possible hopes than collapse into neurasthenia. Certainly this is the time for patience. France has been in crisis since 1932. No one is doing any building. And the flag must be kept flying, ready for the moment of rebirth.”42

Meanwhile, once Le Corbusier had an idea in mind, he did not let it drop. The architect was working on “a museum for unlimited growth.” The project was an elaboration of his earlier scheme for a contemporary-art showcase in Paris and of the concept he had pitched to Nelson Rockefeller. Again it was built from inside out as a square spiral and was capable of indefinite expansion, with the idea that what was an exterior wall on one day would become an interior one the next. But now it was a structure raised on pilotis, entered at its center, from underneath.

Le Corbusier wrote his mother on June 3, 1939, from Fleming’s Hotel on Piccadilly in London telling her he was developing the scheme for an American client—“Guggenheim, the copper king of New York,” to whom he was about to present it.43 This was Solomon Guggenheim, the man who ultimately was the chief patron of the great art museum that bore his name when it was completed in New York in 1960. Hilla Rebay, Guggenheim’s art advisor and emissary, was with him at that presentation in London. She very much liked the square spiral of ramps and the idea of entering into the core of a building that worked from inside out.

Four years later, Rebay began conversations with Frank Lloyd Wright about a museum structure to be funded by Solomon Guggenheim. The spiral that Wright designed for that patron was circular rather than square, finite, vertical, and with a large central atrium. Nonetheless, Le Corbusier’s revolutionary idea for a linear presentation of modern art, with the visitor moving continuously around a central axis in a progression that broke the mold of exhibition architecture, was possibly at the root of Wright’s idea, having been communicated by Rebay and by Gugggenheim, even though Le Corbusier never made the claim or tried to take credit, any more than he ever proposed that the ramps at the villas La Roche or Savoye had influenced Wright’s museum design.

12

On September 3, France and England declared war against Germany. Le Corbusier was officially relieved of all military obligations because of his age, and his swimming accident and his vision problem disqualified him from volunteering as a soldier anyway, but he wrote to three different friends with high government positions seeking employment that would be of maximum usefulness to the country.

At 5:00 p.m. on the day war was declared, Le Corbusier wrote his mother, “We are—each of us—quite incapable of facing events with any sort of mastery. The unspeakable is occurring quite mechanically, with no regard for human sensibility.”44 The next day, he and Yvonne left Paris.

They first went to Vézelay, a lovely hill town in Burgundy where their friend Jean Badovici lived and that has one of the most splendid of all Romanesque cathedrals. Le Corbusier wanted Yvonne to be in a place where she felt comfortable; he figured he would wait there, too, until he was somehow called to action. Pierre Jeanneret, meanwhile, went to Savoie, and Albert and his family accepted Marie Jeanneret’s invitation to install themselves in Vevey.

Le Corbusier wrote his seventy-nine-year-old mother, “Your fate may be as perilous as ours…. Yet I hope that Maman will be sheltered from it all. We must now see reason and realize, quite simply, that we have insufficiently appreciated all the years that were without pain.” Just as he had stayed calm when his leg was severed, he was determined to make sense of a senseless world. “Impossible to speculate about the future. Will the conflict be short or long? Unknown. Whatever the case, the consequences will be crucial. Ripeness is all…. I’ve already told you where I believe the heart of the matter is: a reorganization of consciousness and a major revision of the conditions of life.” Le Corbusier believed his imperative was “as much as possible, to pursue life, to create, to act, not to halt.”45

The times were, of course, undeniably treacherous. On September 27, he wrote his mother and brother, “I am almost ready to acknowledge that the situation is so far beyond human capacities that it cannot be mastered by anyone.” Yet the “almost” was key: he was confident that “the new cycle will begin…. One thing is certain: men will leave their shoes behind and put on new ones.”46

Le Corbusier hated “Germany infatuated by its belligerent violence, a violence so dense and heavy it terrifies us all and must be destroyed.” But he still saw the world as being on the verge of positive change and welcomed war just as he welcomed fire. Anything was better than stagnancy; destruction was always the preamble to construction: “There are great demolitions only when a great building site is about to open,” he assured his mother.47 Devastating as it was to see civilization pulverized, he was convinced that the losses would pave the way for him to design and build.

13

Jean Giraudoux was writing an introduction for Le Corbusier’s Charter of Athens. In July 1938, Edouard Daladier, France’s prime minister, had appointed Giraudoux head of the Information Commissariat, which made him responsible for French government propaganda and gave him great influence. Giraudoux believed that even if France lacked the economic or military power of other countries, it was distinguished by “the moral nature of her form of life.”48 He also had strong ideas of national self-improvement. The writer favored a firm policy concerning the physical well-being of French citizens, calling for active participation in sports and a comprehensive campaign against tuberculosis. Beyond that, he envisioned more urban planning.

To his mother, Le Corbusier described the opinionated playwright as “a sympathetic type—a splendid head, very sensitive.” At the office on the rue de Sèvres, because of connections made through Giraudoux, the staff was working on “an excellent enterprise for temporary barracks, primarily for the refugee schools.”49 Requested by the national minister of education, these structures could be taken apart, moved, and reassembled as clubs, nursery schools, studios, or housing, depending on need. Le Corbusier believed that they would become prototypes for building throughout the country.

In the second week of October 1939, Le Corbusier returned to Paris from Vézelay for a meeting he had arranged with Giraudoux. Its purpose was the creation of Le Comité d’études préparatoires urbaniques. The goal of this organization was to plan the work that might occur in peacetime, once this dreadful situation was over. After the two men met, Le Corbusier wrote his mother, “The interview was really a moving one. I believe we are the left and right hands of a single body.”50

Giraudoux invited Le Corbusier to lunch ten days later so that they could talk in greater depth. The encounter inspired one of Le Corbusier’s epiphanies: “And then I felt that the way lay open and that the hour of realities was striking…. It was some fifteen years of preparation that were bearing fruit.”51

Infused with confidence, Le Corbusier set about meeting other influential government officials and their aides. His movement in the corridors of power paid off; he discovered that people high up in the Education Ministry had read his work and wanted to hear his ideas: “Result: the decision is up to me. Up to me to offer these men laden with cares a clear and objective plan. Giraudoux’s views are lofty—total. At last, the scope of human beings is here equivalent to the scope of events.”52

Having secured the necessary backing, Le Corbusier said that the purpose of the new organization he would run under Giraudoux’s authority was “to establish juridically, legally, the status of urbanism in France and in the colonies.” His role, which he outlined with pride to his mother, was “to be the instigating, doctrinaire cell.”53 He could now put Giraudoux’s lofty ideas into effect.

Jean Giraudoux considered France an “invaded country” suffering from having welcomed too many refugees; this “continuous infiltration of barbarians” was bringing the nation down. The playwright favored a draconian immigration policy that would incorporate “pitiless surveillance” and “send back those elements which could corrupt a race which owes its value to the selection and refining process of twenty centuries.” Foreigners were “swarming in our arts and in our old and new industries, in a kind of spontaneous generation reminiscent of fleas on a newly born puppy.” He lamented the “Arabs polluting at Grenelle,” the “Ashkenazis, escaped from Polish or Romanian ghettoes…who eliminate our compatriots…from their traditions…and from their artistic trades…. A horde…which encumbers our hospitals.”54

Giraudoux wanted to create a minister of race. The man whom Le Corbusier called the other hand of the same body, whose book he urged his mother to read as the epitome of rectitude and grandeur, declared—in that very book—“We are in full agreement with Hitler in proclaiming that a policy only achieves its highest plane once it is racial.” Giraudoux distinguished himself from the Germans with their search for the perfect Aryan by emphasizing “moral and cultural” qualities rather than physical ones, but nonetheless pointed out that immigrants “rarely beautify by their physical appearance.”55

Was Le Corbusier overlooking these ideas in a blindness induced by the rekindled hope that he had found the means to build his ideal cities? Now that the Swiss, the Soviets, and the Americans had let him down, was he simply convincing himself of Giraudoux’s merits because he thought Giraudoux would allow him to construct on the scale of which he dreamed, or were these thoughts about other races his as well?

14

Le Corbusier stepped up the pace of his return trips to Paris. By the end of November, the arms minister, Raoul Dautry, had asked him to design a large munitions factory intended mainly to produce shotgun cartridges. Dautry gave the architect the rank of colonel and Pierre Jeanneret that of captain. In this time that was the start of a nightmare for many in France, the office staff was increasingly productive.

The onset of winter weather changed that. Since there was no heating oil available, it was impossible to keep the office open and continue staying at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli. Le Corbusier returned to Vézelay. Back in the Burgundian village, he painted, worked on large panels, and read English detective novels. He wrote his mother little domestic reports: “Yvonne’s eyes ever dynamic: dynamite.”56 “Pinceau wants to make pipi, Pinceau wants to make caca.”57 He also reflected on the changes he hoped to effect in France:

The country needs several kicks in the ass. There is too much dust and dirt, too much sleep, too many false terrors and ghosts. And too much love of money. Money is over and done with.

It’s all coming to an end, and when it does, we shall have won back the true values and the spirit of things.

Hope is in season.58

IN A LETTER to Marguerite Tjader Harris from Vézelay, Le Corbusier wrote that in his new job he was accepting only the salary paid to military people on the front. He hoped to sell enough paintings to provide the additional funds needed for his way of life—not easy since for seven years his architectural practice had been in what he termed a “dépression,” with no work at all.

Desperately, he asked his mistress in Connecticut if she or her friends could buy his paintings—abstract or figurative, gouache, watercolor, or pastel. He said he would sell them starting at thirty dollars each. Now praising Americans for sympathizing with the French cause, he believed that, if they understood his dire financial straits, they would be more willing to purchase his work. Tjader Harris did what she could to help. She looked for collectors and agreed to give up her translation fee for When the Cathedrals Were White. Le Corbusier regularly took his secret letters to the Vézelay postbox without Yvonne knowing what he was doing. But in his own way, he was loyal to his wife, writing Tjader Harris that Yvonne was “strong, pure, whole, clear. I have great admiration for her. She is a peasant girl, as I have told you. For me, a perfect companion. But I must remind you that I, too, am a fine fellow.”59

15

That December, Le Corbusier told his mother that the shortage of trains would make it impossible for him to go to Vevey for the holidays. He reported diplomatically that Yvonne insisted he make every effort to get to Switzerland without her, but that was not feasible.

A week before Christmas, Le Corbusier wrote Marie,

A good nap leads to collapse. Doctor Carrel, whom I saw last Thursday, told me as much: comfort annihilates the human race. There must be struggles. So don’t take life’s difficulties (whatever they may be) as catastrophes, but rather as good hygiene. It’s what makes life possible. For if the contrary point of view prevails, everything seems merely disaster.

We have philosophized with Carrel down to the last issue—the search for what is best for mankind, and we are in perfect agreement: the power to create, to intervene, to act is our lifeblood. Otherwise, deterioration. Carrel will work with us.60

Alexis Carrel, a scientist who had won a Nobel Prize and whose wound treatment had benefited Le Corbusier after his swimming accident, had published, in 1935, the best-selling Man, the Unknown. In it, he insisted on the most traditional gender differentiation: “The sexes have again to be clearly defined. Each individual must be either male or female, and never manifest the sexual tendencies, mental characteristics, and ambitions of the opposite sex.”61 The primary role of woman, Carrel maintained, was to bear children.

Whether he subscribed to every word of that best-selling book, this was the man with whom Le Corbusier described himself “in perfect agreement.”