XLI

1

In February 1949, during a brief stopover in New York on his way to Colombia, Le Corbusier wrote Marguerite Tjader Harris, asking her to organize a meal in a good restaurant. His instructions were specific. The event should be planned by her, but he would pay, and he did not care what it cost. The restaurant could be Italian, French, or Spanish. The following women should attend: herself, Helena (for whom he gave two addresses but no last name), Barbara Joseph, and Mitzi Solomon. He had, he explained to Tjader Harris, met them all in 1946 and 1947.

Anticipating the event, he explained: “Life and hell and paradise are the walls in which there are sometimes doors, keyholes, openings, and sometimes the door itself opens…. So in the difficult life I lead, the entrance to consolation may open to me.”1

He told Tjader Harris that while the UN had thrown him into despair, she and these other women represented “the great New York I love.”2 His haremlike rendezvous should occur at the start of March, when he would be stopping in Manhattan on his return to Paris from Bogotá.

Le Corbusier was ebullient because he had signed a contract with the Colombian authorities for a pilot plan for Bogotá, then in a period of rapid growth with its population jumping from half a million to one million people. He planned to divide the Colombian capital into distinct sectors, fulfilling his dream of designing an entire city with a unifying, modular element as its basis. He was more the product of La Chaux-de-Fonds than he acknowledged. Having grown up in a grid of neat blocks, he was now trying to impose its rationalism and systematization on a more exuberant metropolis. Importing European civilization into a distant territory, he had the mentality of a conqueror.

Le Corbusier commuted to Bogotá until April 1951, when the completed plan was officially accepted. That victory sent him into one of his upward swings. With Bogotá on top of Marseille, he became convinced that, finally, his patience had paid off. This time he declared that the duration of his waiting period had been forty years. He also felt he was making strides in his painting.

The only area in which victory still eluded him concerned his mother and Albert. He urged them to spend ten days in the mountains—he would pay—but they refused. Offering gratuitous advice to a stubborn eighty-eight-year-old, he again instructed Marie Jeanneret to enjoy herself more and reminded her that life would pass quickly. Then on July 18, the architect wrote his recalcitrant mother and brother on the official letterhead of the Conseil Economique—for which the sole address line was “REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE LIBERTE EGALITE FRATERNITE.” His tone was huffy. He had written them ten days previously, to say he would be in Bergamo—in northern Italy, not so far from the Swiss border—between the twenty-second and the thirtieth, and he wanted to visit them for a couple of days. They had not, however, had the simple courtesy to respond.

Le Corbusier told them he was enraged by their silence. If they did not signal that he was welcome, they would miss their chance to see him for a long time, since during his summer holiday on the Côte d’Azur, he would be meeting with Sert and Wiener about Bogotá and would not possibly have time to break away to Vevey. “Answer. I am in the grip of a very active life. A simple word, if you please.”3

THERE WAS AN ENCLOSURE with the vituperative letter. It was a copy of a translation of a letter from Pedro Curutchet. Curutchet, a doctor who lived in La Plata, Argentina, had commissioned Le Corbusier to build him a private house. It had been a long time since Le Corbusier had worked on a luxury villa, and he wanted his mother and brother to know what was being said about the plans he had made.

Curutchet admired “the graceful and transparent structure” and “the harmonious continuity everywhere.” The aesthetic perfection of the spaces was not all the doctor praised.

But after this first impression I look more closely and in each detail I discover a new interest, a new mirror of intellectual beauty. Henceforth I realize I’ll be living a new life, and later on I hope to assimilate completely the artistic substance of this architectural gem you have created.

People I have shown the plans to have been enchanted. I know this work will remain a kind of lesson of contemporary art, of your avant-garde mind, and of your original creative spirit. My duty will be to see that everyone makes use of this lesson to the benefit of his own culture and in gratitude to the great master.4

The house for Dr. Curutchet is one of Le Corbusier’s most spectacular luxury residences. To build a private palace out of reinforced concrete was audacious; so was the lively and irregular plan. The house is an exciting jungle of terraces, interior gardens, courtyards, large rooms, and great cantilevered roofs, with brises-soleil and pilotis at every level.

Curutchet, another of Le Corbusier’s ideal clients, was, in his own field, as independent as the architect was in his. A doctor who performed home surgery in a rural region nearly four hundred miles from La Plata and Buenos Aires, he was obsessed with the idea that a surgeon’s hands needed to be in their most comfortable and functional position for a successful procedure. To this goal, he developed special instruments for what he named the “aximanual” technique—in comparison to the “crucimanual” technique, in which the doctor’s hands were cramped in order to cope with awkward, old-fashioned tools. Not only did Curutchet have in common with Le Corbusier an abiding interest in the human hand, one of the greatest of all mechanical devices, and a wish to use modern technology in new and unexpected ways, but the erudite doctor wrote long books to explain his theories with references to people ranging from Bach and Delacroix to Stravinsky and Valéry.

Wishing to move back to La Plata to live in a combination of house and surgical clinic, Curutchet had acquired a small building site opposite a park. Once he decided that Le Corbusier should design it, he had his sister, Leonor, and their mother meet with the architect in Paris. Following that meeting in September 1948, Le Corbusier came up with a design for a 531-square-meter house to be built for about $32,000. With Amancio Williams as the site architect, the house was completed in 1954, and although Le Corbusier never actually saw his own creation or met his client, the project had served a wonderful purpose by providing the adulation that he could forward to his mother.

2

Le Corbusier’s mother and brother failed to encourage him to visit from Bergamo. He let his mother know that, therefore, instead of going to Vevey at the start of August after attending CIAM, he made the short trip across northern Italy “in order not to see any more architects and to get a whiff of that great, real-life poetry which is in Venice.”5

On August 1, from his albergo near the Piazza San Marco, he also wrote Yvonne, who was alone in Paris. Le Corbusier wanted her to understand that he was away on this date when most French husbands started their family vacation only because of the obligations of his work. But even the glories of Venice did not distract him from his highest of all personal priorities:

The true site of my happiness is my home, which you illuminate and make so beneficial by your presence. Guardian of the hearth. Your magnificent gift of remaining young and beautiful by means of the profound character within you.

Everyone says of you the best that can be said and of 24 N-C that it is a unique site.6

Sitting near the spot where, when he was twenty years old, the sunshine following seven inclement days had suddenly opened his eyes to the miracles of architecture, the sixty-one-year-old had another moment of revelation: “My life often transports me into glories to which I am indifferent and into the realm of imbecilities that drive me mad and wound me. When I return to 24 N-C, I return chez moi, chez nous.”7

Le Corbusier assured his wife that, if she had been at CIAM with him, she would have been loved by his colleagues. But the trials and tribulations of the trip would have been untenable for her. Consoling her, he reminded her that they were about to spend a month in her home territory in the south of France.

AFTER ONE NIGHT in Vézelay and the next in Avignon, Le Corbusier and Yvonne reached Menton—not far from Nice—where they stayed at the Majestic Hotel. Almost as soon as “M. et Mme. Le Corbusier” checked in to their grand hotel at the seaside, Sert and Wiener arrived, and Le Corbusier began to work day and night on plans for Bogotá. He did, however, manage to swim twice every day, once at noon and again at 6:30 p.m. Then, after Sert and Wiener left on August 22, Le Corbusier started to restore the murals that had so upset Eileen Gray in E. 1027 in nearby Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. The murals had been damaged during the war by the occupying army, and Le Corbusier worked on them for the next nine days.

The heat was terrible in the south of France that August, but Yvonne was happier than Le Corbusier had seen her in ages. At lunch and dinner, the couple ate without fail “in a casse-croute 15 yards from the villa, a pleasant new building run by a good sort, patronized by campers and hitchhikers etc…. a simple and honest and humorous humanity, a friendly intimacy and a real match between Panam and Midigue [slang for Paris and the south of France]. Hilarious contests, sometimes lasting hours. This couldn’t be better for us. And from this shed an extraordinary view of Monaco, night and day.”8 The term “casse-croute” meant a simple shack or lunch stop where people ate straightforward local food, which Le Corbusier described with relish to his mother and brother. He advised that they, too, take advantage of the time of year at the edge of a vast and beautiful body of water.

LE CORBUSIER was portraying the very spot that was to be his definition of earthly paradise for the remaining sixteen years of his life. The restaurant was l’Etoile de Mer. The “good sort” was Thomas Rebutato, who with his wife and son were to be the saviors of Le Corbusier’s and Yvonne’s later years. That lunch stop would be the place where Yvonne would get her six dozen sea urchins a day, where the two would drink their pastis together and look over the sea toward the land of her birth.

THOMAS REBUTATO, who had been a plumber in Nice, had bought a parcel of land near E. 1027 in 1948. Where he had opened his simple restaurant, mainly to serve grilled local fish to students, he also built a couple of modest cabanons for vacationers.

One day, when Rebutato was sitting on the terrace at l’Etoile de Mer, a man came up the hill from E. 1027 and asked the restaurateur if he could provide lunch for twenty people. If the lunch went well, he said, he would ask Rebutato to do the same on various occasions in the upcoming days. After the repast, a great success, the man identified himself as Le Corbusier.

At lunch with Yvonne and others at l’Etoile de Mer, late 1950s

The former plumber, his wife, and their twelve-year-old son, Robert, were among the rare people who could get along equally well with Le Corbusier and Yvonne. Rebutato spoke with the thick southern accent of the villages that dot the Mediterranean coast. He stood for hours each day behind the bar of his little restaurant in the summer heat, one hand often placed firmly on the wooden counter, the sleeves of his baggy white shirt rolled up to reveal his darkly suntanned arms, his shirt buttons open to the navel. He sported a beret at jaunty angle even in the warmest weather. Invariably he had a cigarette clenched between his teeth, with an ash dangerously close to falling. His personal style made Le Corbusier and Yvonne totally comfortable.

Le Corbusier soon gave Robert a model of the Modulor and began discussions with the boy. Within a couple of years, Robert decided to be an architect; a decade later, he wound up working in Le Corbusier’s office. Yvonne was very maternal with him; she loved to tell Robert stories, and he sang to her.

In time, Le Corbusier and Yvonne lived on this hillside in a structure that resembled a mountain hut—or one of the single monastic dwellings located in the wilderness on Mount Athos. It had everything the architect wanted—the bare necessities for living and working, and a large window opened to the vast horizon. This was where, until Yvonne’s death, they slept at right angles in their single beds, hers elevated on a base that contained storage bins, his only a mattress, with a low square table, also providing storage space, in the void between them. Le Corbusier stayed on, summer after summer after Yvonne died, and he moved to her bed.

Writing his euphoric letter from the modest seaside restaurant in 1949, Le Corbusier was also within view of the spot where he would ultimately join himself to the sea and the universe. But there was still much to do—and a chance to impress his mother.

3

José Luis Sert let Le Corbusier know that Picasso wanted to visit the construction site in Marseille. Le Corbusier wrote the Spanish painter, “With pleasure: you give the orders. The sooner the better, as I’m always at the mercy of unexpected problems.”9 He asked Picasso to send a letter or telegram in care of l’Etoile de Mer because there was no telephone, and advised Picasso to meet him at the Roquebrune-Cap-Martin train station on any morning he proposed, as early as 7:00 a.m. This was the sort of scheduling of which he had once dreamed.

ON SEPTEMBER 11, Marie Charlotte Amélie Jeanneret-Perret, who was born in 1860, would, it was said, turn ninety. Only nine years earlier, she had turned eighty. With his passion for round numbers and his impatience to have his mother reach one hundred, Le Corbusier had moved the clock ahead. There is no sign that she argued with the idea.

The architect drew a schema to suggest the perfect divisions of his mother’s life as she reached the harmonious sum of decades. It was a vertical figure poised on a horizontal line. Two ascending lines curve upward in opposite directions, crisscrossing at the thirty-year mark, then diverging again, meeting a second time at sixty, then veering away again, and joining up for a third occasion at ninety. The ninety is a summit, a moment of harmony and union.

The loyal son explained the drawing in a letter sent on September 7, 1949: “Now three cycles of life have ended, each as complete and pure as the next: nothing has failed. A splendid ascent. All my respect, all my admiration. It is the third one that you have achieved ahead of any of us. It seems to me that in our family one grows young.”10

On the previous Sunday Le Corbusier had been with the seventy-nine-year-old Henri Matisse, “pink-faced, entirely white hair.” The architect was deeply impressed by the way Matisse, “nailed to his bed for ten years,” was using a three-meter stick with a charcoal at the end to design the interior of the chapel at Vence and managed to cut forms out of colored paper and arrange them rhythmically. “He has found the key,” Le Corbusier wrote about this artist he failed to understand as a young man. For two hours, Matisse regaled the architect with “a whole heap of stories, all of them gay and playful.”11

Le Corbusier added that nearby, in Golfe Juan, the sixty-seven-year-old Picasso had just had a baby girl. Le Corbusier, too, was feeling revitalized, thanks to the role model to whom he was writing: “And following the example of his mother, at sixty-two [sic], at a time when all other comrades are falling out of the race, Le Corbusier begins a new thirty-year cycle.”12 On September 11, she would, he reminded her, begin her fourth cycle; she must live to be 120.

He would not actually attend the birthday celebration—Marseille beckoned; work had its priority—but he enclosed a newspaper article as a reminder that “the younger son has finally taken his worthy place on the track.”13

4

In late October, Le Corbusier told his mother that he had been filmed for two days on the construction site at Marseille “as a kind of ‘star’ with Jean-Pierre Aumont” and that the building there was beginning to take shape; the skeleton of the fifty-six-meter-high structure was in place even if the walls and the rest of the superstructure still had to be added. A new “association for a synthesis of the fine arts” had been created that year of which he had been appointed the first vice president, “which is to say, the man in charge,” and he was planning a show at the Porte Maillot devoted to this coming together of the visual arts. He had also just finished the factory at Saint-Dié, where he had manifested that unity of the arts by incorporating his own painting and sculpture within his architecture. But then he observed to Marie Jeanneret and Albert, “My dears, here I am again chattering of egoistic matters,” and went on to discuss the new automatic heating system he had installed in the house in Vevey as if it were the most important thing of all; his mother had not yet mastered it, and must do so before the onset of cold weather.14

Le Corbusier closed by telling Marie that he would be writing to Marguerite Tjader Harris, for she had remembered his birthday a few weeks earlier.

AS THE WINTER of 1949–1950 approached, the man who was working with state-of-the-art engineers to develop climate controls to combat extreme heat and cold in vast apartment complexes now set out to accomplish the more difficult task of teaching his own mother how to work her furnace. He was determined that she master the new system both for its effectiveness and for the attitude to life its radical technology represented. He concluded his instructions and encouragement, of which every sentence had an exclamation point: “Moral: seize the happy hours as they pass and close your eyes to the others!”15

Not that Le Corbusier followed that advice himself. He did not dissemble about his rage over recent events in America, where President Truman had laid the cornerstone of the UN without in any way citing Le Corbusier as the source of its design. “It’s amazing! That skyscraper is mine,” he wrote his mother. The architect was now constantly barraging Trygve Lie, the UN secretary-general, about the injustice: “Indeed this is an historic event in the history of architecture. I am not letting up. I have all the trumps in my hand. They have robbed me, there must come a day when they admit as much and pay. In what coin? I couldn’t care less!”16

Then, two days after he accompanied twenty journalists via train to the construction site in Marseille, the cinema news, radio, and newspapers all began fulminating against his radical design for the new apartment building. The main problem, he asserted, was that the negative voices had reached his mother and she was upset. He encouraged her to realize it was only the old problem of journalists: “Etc. etc., gazette, late news, press press press!!!”17

She should know that he was walking 1,500 meters every morning, and even though Yvonne was too unwell to write, she was sewing. He advised yet again that one must look on the bright side.

5

One of the press photographers assigned to take shots of Le Corbusier in that time period was Lucien Hervé. The moment the architect saw the younger man’s pictures, he told him, “You have the soul of an architect.”18

Hervé, who worked with Le Corbusier for the next fifteen years, was not impervious to the architect’s cantankerousness, even brutality, but also saw the generosity. At their first meeting, Hervé had extolled the mixture of abstraction and realism in one of Le Corbusier’s paintings. Three years later, the doorbell of Hervé’s Paris studio rang at precisely 8:00 a.m. He knew it had to be Le Corbusier—his only acquaintance who ever came precisely at the hour, never a minute earlier or later, and never having telephoned in advance. Le Corbusier handed the large canvas to Hervé as a gift, saying he knew the photographer had always liked it.

There was only a single exception to the 8:00 a.m. rule. One day, Le Corbusier telephoned Hervé far earlier in the morning and demanded that the photographer come immediately to the rue Nungesser-et-Coli. After hearing Yvonne’s usual complaints about being so far from the center of Paris, Hervé learned what was on Le Corbusier’s mind. The architect was consumed by anguish over news of the proposed exploration of outer space. “He could not understand the interest in space when there was so much misery on the earth.”19 At that early hour, he talked about human values gone astray, the idea that by the year 2000 it would be impossible to drive or park in Paris, and his own determination to help its poor population, who he felt were underserved. He told them that Einstein had said the Modulor could prevent evil from occurring in the world, a goal far more urgent than what the astronauts were doing.

6

As the war-torn decade drew to a close, people eagerly anticipated New Year’s Day 1950. Le Corbusier, however, was, as usual, doing his best to avoid the holidays; he reminded his mother to leave Christmas to children. Besides, Marie Jeanneret had more important things to worry about: she had fallen and broken a bone. The architect begged her to hire an aide, for whom he would gladly pay, but once again she resisted the idea of the domestic help Le Corbusier considered one of life’s necessities.

He then raised the issue of her Christmas present. He had given each of his draftsmen a proof of an engraving he had recently made and had also found presents for their children, but he could not settle on a gift that he was certain would please his mother: “For dear Maman doesn’t like her younger son’s works of art, she thinks it’s ugly, she once declared ‘I’ll never have such painting in my house’!! Andalusian temperament!”20

Worse still, she had no end of admiration for his brother’s music. Le Corbusier ended this pre-Christmas letter to the alleged nonagenarian, “And then, both of you, go listen to those cantatas, the works of Albert the Great. Then happy holidays to you both, and to dear Maman a good year.”21

His conclusion for a Christmas present was to give her The Modulor. It was, he assured her, the latest rage, even though the ink was not yet dry. But he let her know he held scant hope that reading it would afford her comparable pleasure to listening to Albert’s music.

7

On December 30, Jean Badovici wrote Le Corbusier that the architect’s “vanity” concerning the murals in E. 1027 had inflicted great pain and that the pure and functional architecture of his villa had called for a complete absence of paintings: “With your worldwide authority, you have been lacking in generosity toward me. A correction by you seems necessary to me, otherwise I shall be forced to make it myself and thus to reestablish the original spirit of the house by the sea.”22 Badovici then reiterated his love for Le Corbusier, recalling their long history and expressing his hope for a resolution of their problems and wishing the architect and Yvonne happiness in the new year.

Le Corbusier did not bother with any such sentiments in the response he wrote on New Year’s Day. He simply demanded “formally” that the murals be photographed before being destroyed and then accused Badovici of being incomprehensible, which was to be expected since he had never in his life succeeded in writing in a way that others could understand.

Badovici supplied the photos; Le Corbusier’s answer, in its entirety, was “My dear Bado, received your photos of my paintings. Your photographer is a donkey who knows neither values nor cropping nor filters. Couldn’t be worse. I hope he’s not ruining your finances. Best to you, Le Corbusier.”23

He could be as devoted as he could be furious. In 1949, when the Galerie Charpentier, one of the most important in Paris, mounted a large exhibition of André Bauchant’s work, Le Corbusier showered praise with a reach of enthusiasm that was his alone. He wrote the painter, “The soul of the Parisian is in you, consisting of the original soils of each of us and of the fundamental aspirations of the complete man: the love of nature, the forest, the fields, the streams, the need of history, which is the foundation of existence and the love of legends, and your work is full of goddesses, of heroes and sirens, and of God as well. You are a peasant, but in your veins flows aristocratic blood, the miracle of France, where the nobles and gentlemen knew the shepherdesses.”24

His own building in Marseille was to be the architectural equivalent of Bauchant’s paintings: a sylvan ideal that would allow the worship of a sacred landscape. And he was determined that a sense of mythology and pagan worship should course through the bold and colorful structure.

Le Corbusier identified with Bauchant: “You have worked hard, like a man possessed: from dawn to dark.” Bauchant had endured a “heroic struggle in solitude and the mockery of those around you.”25 Even the champions of Henri Rousseau had initially considered Bauchant one step too primitive. That changed only when the dealer Jeanne Bucher saw the Bauchants in Le Corbusier’s apartment, after which she organized exhibitions in her gallery and sold the work to museums worldwide.

The sheer animal naturalness and kindness Bauchant and his work embodied provided relief from the tumultuous disorder of the architect’s own mind. Le Corbusier delighted in being someone else’s savior.

8

The drawings Le Corbusier made for the civic center of Bogotá emanate energy and efficiency. The lithe slabs that would have made up the center of that South American city befit elegant Latin government officials running the affairs of state with verve and élan.

The two main buildings, set perpendicular to each other, are the ultimate exemplar of the right angle, an homage to the sheer panache of two straight lines juxtaposed at ninety degrees. One is basically a calm, horizontal, rectangular block, resting with tapered vertical rectangles at either end; the other is a skyscraper. Yet strong as the architecture is, it is impressively modest in relationship to the landscape; it does not impose itself but respects the mountainous setting, being above all a vehicle for looking out at the earth.

When Le Corbusier flew to South America to try to advance this project, he made it his routine to go via New York. On a stopover there in February 1950, he was incensed by the latest developments. After arriving in Bogotá, he wrote his mother and Albert that he had visited “my skyscraper, very far along but giving every evidence of Harrisson’s [sic] ignorance and lack of imagination. There are horrifying mistakes.” The sight of his great conception—its authorship stolen, its quality compromised disastrously—rendered him almost senseless. He continued, “I’ve touched on so many facts and circumstances…that I’ve conceived a tome (yes, unfortunately!) that will be powerful: ‘The end of a world,’ ‘deliverance.’”26

The “tome” to which he referred was a treatise he had written in his own defense. Published in 1947 by the Reinhold Publishing Corporation, it was called U.N. Headquarters. In the course of its rampage against Americans in general, he mocked the trend for building shelters against nuclear fallout.

“Looked at Harrison’s skyscraper,” he reported to Yvonne. “Poor fools. To massacre such an enormous thing!…N-York is a terrible city. Everyone is quite crack-brained! They’re all abominably scared of being bombed. It’s revolting to see such a strong people showing themselves to be so crazy.”27

But Colombia was different. The port city of Barranquilla, on the Caribbean, asked him to execute a design similar to what he had done for Bogotá, with Sert and Wiener again collaborating. It was a working relationship Le Corbusier prized. Sert and Wiener were “two perfect teammates. We work together to an astonishing degree.” His mother and Albert, to whom he wrote this, knew how rare such a felicitous collaboration was.

“The exactitude of these transcontinental journeys is of a magical order,” he also wrote to those family members who well understood the merits of clockwork. And Bogotá had a lot that New York lacked. “I am regarded as a Gentleman!” he declared to his mother, while describing his thrill at seeing, so far from Switzerland, portraits by Victor Darjou—the same painter who had immortalized his ancestor Lecorbesier at age eighty. “Life strikes me as either magnificent or stupid,” Le Corbusier concluded.28

Yvonne, however, needed to know that he was not having fun. “What a dog’s life! At my age!”29 He complained that the altitude in Bogotá made him feel tired and caused him to have terrible headaches and bizarre dreams. If she thought she was suffering in her solitude and isolation in Paris, she must realize that he was working from 8:30 in the morning until late at night, speaking Spanish, English, and French in a combination that exhausted him. He spent the whole day visiting cities and factories; the workload was without respite. There were good moments—he had had a meeting with the president of the republic and had also enjoyed dinner next to two toreadors, excited that each of those little men with notably small hands had killed two bulls—but he hardly had a moment to himself.

But for both women he had the same rallying cry. Each must find a good maid. This was Le Corbusier’s solution to women’s woes.

9

Yvonne was in better form that spring once Le Corbusier returned from Colombia. Albert came to stay with them on the rue Nungesser-et-Coli, and the three occasionally dined in restaurants with old friends like Léger, Pierre, Charlotte Perriand, and Winter. In spite of Le Corbusier’s professed objection to socializing, there was a cocktail party at 35 rue de Sèvres, where the young staff sang folk songs. Albert wrote to La Petite Maman, “Yvonne makes very funny remarks when she’s in company, and everyone loves her.”30

In mid-May, Le Corbusier made arrangements for Marie to go to Marseille. The trip was possible now that the elevator, which would allow her to reach the roof, was working. Albert was to accompany her. Le Corbusier had organized their travel arrangements in meticulous detail: tickets for the sleeping car on the train from Geneva to Marseille, use of an apartment there for two days, a visit to the construction site. With the aid of his office staff, he had planned every meal, right down to the coffee ice cream that was his mother’s passion.

Then it all had to be scratched, because construction work at l’Unité was behind schedule. Le Corbusier switched the departure date from the end of May to the end of June and reengineered the identical journey. His instructions were explicit: his mother need only take along something to sleep in—“No suitcases, no change of clothes.”31

Then Marie Jeanneret fell from a ladder and gashed her face above her eye. She was not able to travel; Le Corbusier wrote urging her to “give up climbing ladders…out of consideration for her progeny” and put off the trip until she was fully recovered, while stressing that nothing was to stand in the way of her seeing his greatest achievement to date.32

10

At the beginning of August, Le Corbusier and Yvonne took a holiday in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. They rented a bedroom in a shoemaker’s house under olive trees down below l’Etoile de Mer. The hot, sultry days and all his swimming helped Le Corbusier sleep better than he had all year. In high spirits, in a single day he painted a lively mural on a wooden panel along the front of the bar at l’Etoile de Mer. Called Saint André des Oursins, that colorful testimony to the pleasure of summer is a tableau of underwater life, dominated by a smiling sea urchin surrounded by eels, langoustines, flat-fish, and starfish, with a self-portrait of the artist as a jaunty sea bass with a pipe coming out of his mouth and a little bowler hat on top of his head. It fit easily into the setting, with assorted glasses and bottles of pastis and whiskey and wine sitting above it.

A couple of days later, Yvonne stumbled and hurt her knee. It became so swollen that to walk up the steps from the shoemaker’s to the shack was hard for her, but Le Corbusier, in a humor where nothing could damage his sense of the beauty of life, simply profited from their immobility by reading Henri Mondor’s life of Mallarmé. The architect fit Mallarmé’s life into a numeric scheme, concluding that, while Mallarmé had been the greatest poet of the nineteenth century, in 1900 the change of century turned him into a madman. This was one of Le Corbusier’s greatest stretches ever, since Mallarmé had, in fact, died in 1898.

Refreshed by good nights and by days of reading, swimming, and eating fresh seafood, in the middle of August Le Corbusier was off to Marseille before returning on the twentieth to Paris, where most of his office crew was still on vacation. Then, on the twenty-sixth, he would fly on to New York for a two-day stopover en route to Bogotá.

From New York, Le Corbusier used his mother’s impending birthday to write her, saying that, since she liked compliments now that she was getting older, he wanted her to know that she fascinated all his friends. But then he let loose. The architect informed her that she had always been ferocious and readily cruel—either from genius or from ignorance—because of the way she had been raised. He credited her for his having the heredity of a lion, although, unlike her, he was not a lion but a bird.

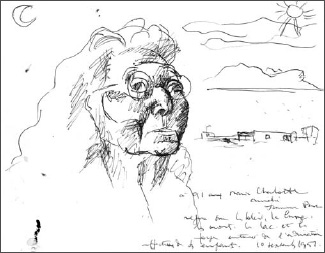

“A 91 ans Marie Charlotte Amélie Jeanneret Perret règne sur le soleil, la lune, les monts, le lac et le foyer entourée de l’admiration affectueuse de ses enfants. 10 septembre 1951.”

Le Corbusier said he owed her almost everything—which, since he was often in life-threatening danger, included the fortitude to survive events and circumstances that would have killed others. He attributed that strength to a mutual bullheadedness, pointing out that the four Jeannerets were all alike, especially in their unwillingness to open themselves to other points of view.33 In this uncensored explosion allegedly written as a birthday congratulation, there was no distinction between mother and son.

DURING THAT STOPOVER in New York, Le Corbusier was even more horrified than before at the fate of the UN. He poured out his anguish to Yvonne: “The architectural spirit in even the slightest details = a grim, dim and insipid flop. Such icy, heartless work leaves us cold.”34

He also emphasized the need for Yvonne to gain weight, telling her what a marvelous surprise it would be on his return if she could become “round as a ball.”35 From Bogotá, he continued his counsel by writing, “Smoke and don’t eat, for my sake,” as if the sarcasm might yield results.36 However, when he advised her that if she needed money for tobacco, she should ask Paul Ducret, his perpetually helpful office manager, he was being perfectly straightforward. After all, Yvonne gave away even more cigarettes than she smoked.

When a woman in Colombia had asked for news of Yvonne and he reported some of her problems, the woman had been dismayed that Yvonne did not take vitamins. Le Corbusier quoted the subsequent dialogue to his wife: “‘Unfortunately, Madame,’ I replied, ‘my wife doesn’t believe in doctors, nor in what I advise her to do; she doesn’t want to take care of herself.’”37 But, six thousand miles away, he was racking his brain to find the right way to cajole her to health, short of being at her side or moving her to where she might have been happier.

Le Corbusier wrote Yvonne every four or five days on that trip. He found some new pills for her that had been recommended by an Australian who took them every day and was in great health; these would be her salvation. When he learned from one of the watchdogs in his office assigned to look in on Yvonne that her health was improving, he was euphoric, writing, “I hope you’ve grown fat as a pork sausage.”38 Meanwhile, he was pleased to have trimmed down a bit; back in New York after Bogotá, he wrote, “You can see in the photo that I’ve grown thinner. The stomach still makes a little hump, but on the other hand, if I go hunting the rabbits can easily escape between my knees! And I used to be so proud of the weight it took me 60 years to gain!”39

He went on to instruct his wife to have Luan, the Annamite houseboy, cut up raw carrots. They would give vitality—the energy and verve essential, equally, to people and buildings and missing in the UN, he explained in one of his soliloquies where the human physique and the nature of a building were inextricably linked.40

11

In October, after he returned to Europe, Le Corbusier was again seeing Hedwig Lauber. The woman whom he had instructed to cease writing to him was now allowed to do so as long as she sent the letters to the office and marked them “personal” Le Corbusier alerted Lauber to his secretary’s habit of opening his mail otherwise.

The architect arranged to see her in Zurich. He planned the evening carefully, opting for a quiet dinner in her flat: “I should like to speak to you in peace and quiet. I want no one else to be present, especially intellectuals. No one. And I do not wish such a meeting to take place in a Swiss restaurant.”41 He said that he would pay for the wine and sausage and slices of ham and would ring at 8:00 p.m.

The bright and attractive journalist was another person who made Le Corbusier happy to be who he was. In his letters to her he described himself as “la bête noire des conformistes”—the autodidact who left school at thirteen, never went to architecture school, never received a diploma, and led “a dog’s life”—whom she put at ease.42 Throughout the fifties, the two saw each other when they could. Their plans often suffered from missed opportunities, however. He could not get her to India when he tried to; she went to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin when he was not there. They had a number of happy meetings, though. Lauber was blond—her hair color an obsession for Le Corbusier, who had spoken about it to Paul Wiener in Bogotá—and she was spirited and happy. She called him “mon cher petit grand Corbu”: small and large, human and great, at the same time—exactly as he wanted to be.43

THAT AUTUMN, there were problems not only with leaks in Vevey but also with the roof of the apartment on rue Nungesser-et-Coli. Le Corbusier was determined that his mother recognize that, even if her villa had rainwater coming in and so did his and Yvonne’s penthouse, he had been asked to build for the world. He was doing an urban scheme surrounding l’Unité in Marseille; plans were under way for a second Unité d’Habitation, in Nantes; he had also been asked to design a chapel in a small mountain village. Le Corbusier continued the litany: in addition, he was working on a hotel in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin and on a different project for Sainte-Baume—this time a building with two arches to suggest the form of a boat for the arrival of Mary Magdalene. He was entering the second phase of the Bogotá plan. His new title was “architectural government advisor…. And that’s only apart of it,” he boasted at the end of November. She must, therefore, accept the leak: “I repeat: All over the world there’s an outbreak of physical disasters (storms and hurricanes) and moral and political catastrophes. To some degree inescapable! Be happy as the Seraphim!”44

Her response was further complaints about her roof. The man who was housing hundreds of families in Marseille could not stand it: “I hope that the moral catastrophe of the leak has evaporated from dear Maman’s heart. When you see what water can do the world over, this year…. And the other elements into the bargain.”45 The only solution left for him was moral superiority.

12

Le Corbusier was determined to use the exposition scheduled for 1952 at the Porte Maillot, on the periphery of Paris, to realize the dream that had preoccupied Ruskin, William Morris, the founders of the Bauhaus, and all the other aesthetic pantheists who had tried to marry painting and architecture and design.

He designed a pavilion that would present the latest contemporary painting, sculpture, and architecture in combination. A bold concept, it was open to the elements on the sides, with a roof that looked like oversized beach umbrellas. The contents were equally audacious: in theory, the pavilion was intended for work by other artists, but in fact it had nothing but Le Corbusier’s own painting and sculpture. It was his ultimate fantasy: a solo Le Corbusier museum displaying his achievement in all the arts, at the bustling entranceway to Paris, visible from his perch on the rue Nungesser-et-Coli.

The project never got past the drawing boards, but the architect was about to realize his urbanism, his building designs, his tapestries, and his sculptures on the scale of which he had long dreamed.