XLVI

1

By the time Le Corbusier got the news of his victory in the lawsuit in Marseille, he was in India. He had returned to Chandigarh following the inauguration of l’Unité.

Yet again, this meant a long separation from Yvonne, who remained sequestered in their apartment. They had by now been together for more than thirty years, married for twenty-two of them; in all that time, the event in Marseille had been the only occasion of her going with him when he traveled for work.

From India, Le Corbusier wrote to her as if to a beloved child: “I hope you’re having a wonderful time in that sumptuous warm apartment looking out on the snow in the street. You’re a lucky girl! You can do your embroidery, read detective stories, be at peace, write to your kid [presumably young Rebutato]. In other words, freedom and happiness!”1

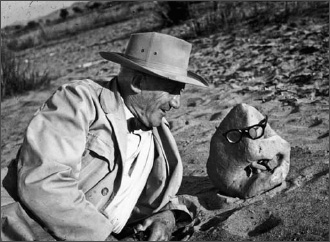

In Chandigarh, mid-1950s

Knowing Yvonne would never see the actual work in India, Le Corbusier sent her sketches of the major projects. While most photographs of Le Corbusier’s High Court and other monuments focus on the buildings alone, in his quick study of it for his wife, the architect drew a number of stick figures in proximity to the form he identified as the High Court. These represented “teams of women dressed in the wildest colors, carrying in baskets on their heads the earth of the foundations and relaying each other in a chain that was like a hallucination.” The drawing was in black ink, but Le Corbusier wanted Yvonne to picture the “the loveliest fabrics dyed brilliant colors.”2

In the sketch, the famous entrance columns of the great court are no taller than those women bearing their loads. The physical reality was otherwise, but that distortion of scale was Le Corbusier’s psychological truth. He did not see architecture as something that should diminish human life and impose itself as a representation of authority—as was often the case with the academic Beaux-Arts buildings he loathed. Rather, he considered building design an integral part of earthly existence that not only respected the natural setting but, equally important, accommodated rather than diminished the ordinary inhabitants of villages and cities.

2

This time, rather than commuting from Simla, Le Corbusier was living in the middle of all the bustling activity in Chandigarh. He was staying in an “extremely pleasant house” in the temporary camp for engineers and architects in the new city.3 He wrote Yvonne about “evenings, [when] everyone sleeps under a thatch of reeds supported by two low walls, and at night the whole place fills up with children and men. This all happens on the site itself, in the dust, among bags of cement, bricks, etc., naked kids running around everywhere. The women never have a place of their own. These people are nomads.”4 Five thousand people were at work on the construction. They worked twelve hours per day, he pointed out to both Marie Jeanneret and Yvonne—reminding both his mother and wife, whose complaints tortured him, of their good fortune.

Le Corbusier imagined Yvonne’s response to these local women with no place to live. “‘At least they can laugh!’ says a charming woman I know in a seventh-floor walk-up,” he wrote her, conjuring the good old days on the rue Jacob. He signed off with “a kiss to the loveliest girl on earth.”5

Le Corbusier wrote Yvonne about Varma: “my friend. A broad mind, a smile: calm, precision, order. In me he finds calm as well, and I can now say: mastery. A life dedicated to such themes has given me that. In contrast with my men here—Pierre and Fry and Drew—how fully I feel in possession of my thought.”6 Yet even if he considered himself one notch above, he was delighted with the progress his less-assured cousin had made. Pierre, who was in charge of a team of young Indian architects, was well liked. Thapar was enchanted with him. Since Le Corbusier’s own house was only ten meters away from Pierre’s, where there was a cook and a valet, he took his meals there.

In the past, Le Corbusier had, at the start of each major project, been totally convinced that he would change the world with it. Now, after years of reversals, he was, to his mother, more skeptical: “The work, which is all my own: the city (urbanism) then the Capitol (five palaces) will be a link in the chain of history…if we come to a good end, without the breaks and catastrophes which have accompanied all my undertakings.”7

Yet the hardships that might have troubled other westerners in this hot and foreign country—the changes of food and diet, the terrible roadways, the crowds, the dirt and dust—were of no note. He had a large office with a view of cows, amiable bulls, and a well-irrigated esplanade of flowers and trees. He loved the way things were done: “All this is accomplished in an administrative calm that delights me.”8

The sky, consistently blue, gave him confidence. And he was again—it was often the case—rereading Don Quixote. “One of the finest, healthiest and most masterful books that was ever written,” he wrote his mother about Cervantes’s magisterial portrait of a dreamer.9

In that mood, he wrote one of his most reverent and, at the same time, critical remarks to his wonderful, infuriating mother: “I see dear little Maman, a lioness in her lair, her face pink and glowing with joy, torn between the moon (the Moonlight Sonata) and the glorious sun of the next washday!!”10

FROM CHANDIGARH, Le Corbusier posted his mother a copy of a letter he had recently received. The first time he sent it was at the start of December. The document was a “Strictly Private and Confidential” declaration from the Royal Institute of British Architects that he had been unanimously elected its Royal Gold Medalist for the coming year. If he would accept the honor and if royal approval was granted, the ceremony would occur on March 31, 1953.

This was all top secret. But Le Corbusier sent it to Vevey nonetheless, with a few lines scribbled on the bottom telling “Petite Maman” he knew it would make her happy. He also underlined the word “confidential.”11 On two subsequent occasions, he mailed her identical copies. He kept sending it until he had some response.

IN MID-DECEMBER, the architect went from Chandigarh to Delhi to start work on a project he was never to realize: the National Museum of India. He then flew on to Bombay.

There, more than in the north, Le Corbusier was dumbfounded by the serious food shortages and other problems posed by population density. At a lunch gathering of people in important positions, the architect predicted that in ten to twenty years there would be seven hundred million Indians and widespread famine. Another lunch guest commented that it was essential to suppress hormones, to which Le Corbusier, livid over the imperiousness of anyone suggesting that the masses would be better off with less sexual drive, retorted, “It is hypocrisy that must be eliminated.”12

From Bombay, the architect caught a direct flight to Paris. Landing at Orly on a Saturday, he maintained his breakneck schedule with meetings all day Sunday. On Monday, he worked at the office until the last possible minute before taking the train south to spend the Christmas holiday at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin with Yvonne. In the midst of it all, he suddenly realized that he had committed a great oversight. He had forgotten to give de Montmollin instructions to transfer the funds for a turkey for his mother and Albert to eat on Christmas Eve.

That failure was a signal: he was overworked and exhausted. He now confided to Marie Jeanneret that he would probably turn down the request for the British honor. Work and his mother’s needs had to be priorities; there was no time to waste.

3

Back in Paris after the winter break in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Le Corbusier renewed his frantic pace. His busy life was possible thanks to his great physical fitness, about which he became increasingly diligent. He began working out with a private trainer named Doyen, who came to the apartment every morning at 7:30 for half an hour; Le Corbusier liked his company and the way he felt after the exercise. His morning routine now consisted, first, of serving Yvonne her morning coffee in bed; then she lay there while the house shook with his calisthenics. Her limp had worsened, and she now had difficulty walking even with a cane, so she waited for him to come back before getting out of bed.

In February, he decided to accept the medal in London after all. To his mother, he feigned modesty, insisting that the applause did not interest him; while four banquets were planned, he agreed to only one. But of course he wanted her to be impressed. The architect wrote the widow a description of Queen Elizabeth: “She’s quite sympathetic, this little woman.”13 He didn’t bother with more description; for a man of his importance, with such a great mother, seeing the nice “little woman” was a routine event.

The architect Berthold Lubetkin was given the task of showing the honoree around London. Lubetkin asked Le Corbusier what he would most like to see; the answer was the corner of Oxford and Regent streets. The gold medalist cared less for architectural monuments than for being at the crossroads of a bustling metropolis and feeling its pulse; nothing by Christopher Wren or Inigo Jones interested him as much as the heartbeat of urban life.

WHEN HE RETURNED to the Paris office, Le Corbusier began to finish up his projects for Ahmedabad, which now included a museum in addition to the Villa Sarabhai and the Millowners’ Building.

Work was moving ahead on Ronchamp, and construction on Nantes was to begin April 1. Marseille was garnering further praise, and Le Corbusier had progressed with what had become two splendid houses for André Jaoul in Neuilly and was giving further consideration to the convent near Lyon, the project that would evolve into the magnificent La Tourette.

Fired with confidence, Le Corbusier imbued his mother with the flair and force he was feeling himself. On March 1, he wrote her, “Your letters are (always) a ray of sunlight. You have a happy soul, playful and strong. For us it is a blessing to see you cock a snook at the coming century with such a youthful heart: Madame centenarian. Ordinarily old age makes us tough. You know how to see the sun where it is and the blue sky and the lake. You’re tough only for housework—work, work, work. And really, what does that matter? All of us forge our own chains, which establish the frontiers of our action.”14

Now in his midsixties, questioning how he would manage the ultimate phase of his existence, Le Corbusier was evaluating his own capacity for life and its pleasures. His mother’s longevity thrilled him, but he knew it had little bearing on how long his own biological clock would run. She was his role model for energy and work ethic, though—the main difference being that the compulsion to do well had her at the washbasin and him at the drafting table.

4

In March, one of Le Corbusier’s dreams came true. His mother agreed to go to Marseille to see his building. She would be accompanied by Albert.

Le Corbusier organized the details of the voyage. He bought second-class train tickets from Vevey to Paris, with a departure scheduled for April 5. He would be at the station waiting for them. After about a week in Paris, Marie and Albert would take a sleeping car to Marseille, where they would spend a day at l’Unité before returning the following morning to Geneva. He drew diagrams to show the logistics of the trip.

That was plan A. With Marie Jeanneret, nothing was ever simple. A week after the initial proposal, Le Corbusier’s secretary wrote to say that she could travel “3ème classe” if she absolutely insisted, but that she really should not hesitate to pay the supplement to travel via “2ème classe” to be more comfortable and in order to have lunch in the dining car. Now a friend would drive them to Marseille and, afterward, from Marseille to Vevey—so that Marie could be spared a complicated and exhausting train journey on the return. The secretary concluded, “M. Le Corbusier hopes this plan is to your liking and is delighted to be seeing you again.”15

All was in order. But just before his mother embarked on the journey, Le Corbusier scribbled off a word of warning. Yvonne had “a nervous condition” her hyperthyroid imbalance made her occasionally violent. “So, dear little Maman, you whose blood also occasionally acts up, be a good girl now and a grown-up. Yv is a little girl, utterly devoted, correct and generous. But she’s sick now, as well as suffering from very painful rheumatism + her lame leg. So: no lectures about hygiene, no reflections or animadversions about tobacco or drinking. Yvonne is stubborn, nothing you can do about it, don’t even try. All of us must follow our own path, our own destiny, our own instinct.”16

His two worlds were again about to collide. With his mother, at least, there was some possibility of control.

THERE IS NO KNOWING how things went between “Vonvon” and “La Petite Maman,” but photographs testify to the successful visit of Le Corbusier’s mother to the building in Marseille. The white-haired lady from Switzerland can be seen beaming in the modern skyscraper that was so totally different from the world in which she had nurtured its architect. His, perpetual wish for her to be proud and happy was, however briefly, again realized.

5

After the triumph of Marseille, there was no stopping Le Corbusier. In the early spring, he wrote his mother, “I lead a dog’s life here, very difficult. Or a cab-horse’s, as I said in my London lecture at the end of March.” He was further exhausted because of the shots of anticholera vaccine he had to take to prepare for his next trip to India, as well as by struggles over the Unité proposed for Nantes, where he was battling “bastards (at the top of the profession)”—the underlining reflecting his usual rage at the practice of architecture. But the Tate Gallery had bought his most recent painting, magazine articles about his architecture were appearing all over, and a large catalog was in the works for a major exhibition in Paris that fall. He told his mother about all of it and more, while tempering his glee: “Dear Maman, I’m bothering you with all my troubles. You know what kind of a life I must lead. Everything becomes harder and harder: responsibilities and the Responsibility.”17

While he was beleaguered by obligations, Marie Jeanneret, at least, should free herself of the shackles of domesticity and enjoy the liberation he intended to give all women. Le Corbusier linked his own mental state to hers: “You mustn’t lead such a life ‘at the lake’—housework and laundry, etc., along with everything else. I want Maman to let herself go!!! For God’s sake!”18

HIS SIX WEEKS in India at the end of May and into June were a welcome respite from his frantic life in the west. His spirits were raised even more when he got word that the French minister had agreed to the project in Nantes, which transformed itself into an outburst of warmth toward his mother. Le Corbusier attributed his success to her, writing, “You are a great woman, worthy of the great historical periods.”19

The heat in Chandigarh was oppressive that spring. This prompted Le Corbusier to draw for his mother a remarkable self-portrait to illustrate an Indian bath. The technique was to take a bucket of water that came out of the faucet at forty degrees Celsius and throw it on his body with a metal ladle. Le Corbusier’s sketch shows his balding head, with beaklike nose and glasses. The image of him dousing himself is full of life and humanity. It is also astonishing. For in this self-portrait drawn for his mother, his sagging testicles are clearly visible in profile, as is his penis, with a drop falling off its tip.

An Indian bath: self-portrait drawn for his mother, 1953

TO COUNTER the Indian heat, Le Corbusier would cool himself with a fan, then drink boiling-hot tea, and, at night, down a whiskey under the mosquito net on the lawn in front of the house; he had changed his stance on alcohol. He wrote his mother assuring her that what he was achieving in India was going to be a sensation. It was “raw concrete, as sharp and clear as Egyptian or Greek architecture: a great step forward.” Adding to his joy, he had a recent picture of his mother with her “lovely nostrils,” which he looked at all the time.20

Everything was for the best. Pierre was happier than he’d ever been; Le Corbusier even convinced himself that Yvonne was fine. Although she could no longer leave the apartment, he had organized someone to come in and play the accordion for her. If one made the effort to focus on joy, it could always be had.

6

Le Corbusier returned to Paris from India on June 21. The following day, Douglas Dillon, the American ambassador to France, awarded him “the rosette” of the American Institute of Arts and Letters, with a diploma naming him as an honorary member for his service to architecture. The induction ceremony at the American embassy might have been the beginning of a reconciliation with the United States. However, five days later, the United States and England definitely vetoed Le Corbusier’s design for UNESCO. It baffled him to be turned down by the two countries from whom he had recently received official honors. “Reign of the mediocre and triumph of the timid,” he wrote his mother, to whom he had proudly sent a newspaper clipping about Ambassador Dillon.21

The summer, however, was more restful than usual. Le Corbusier and Yvonne left for their hideaway in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on July 17 and settled there for an unprecedented six weeks, in which the architect swam, caught up on sleep, and painted twenty watercolors for a new project with Tériade. Twice every day, he and Yvonne repaired to l’Etoile de Mer for their pastis and seafood.

Then, in September, Le Corbusier left Roquebrune-Cap-Martin for Paris with such a bad cold that he traveled via train in a sleeping car rather than fly or drive as usual. The illness turned into severe pneumonia; for six days, he had a fever of forty degrees Celsius. Too sick to read or work, he passed the time lying in bed and listening to the radio.

The radio was almost dead—he had great difficulty getting reception—but, with much effort, he managed one afternoon to tune in to the Wagner opera Tristan and Isolde. In his feverish state, he wrote to his mother about hearing “the indefatigable duet and the orgasm. Then I said to myself: I’ll send dear Maman a note to tell her what tremendous emotion I experienced hearing this music you so love and respect and that I admire and ‘consume’ for reasons different from yours: yours are those of a musician and mine of the life experienced precisely where communion is possible between two human beings. If all the reasons were put on the table, it would be apparent that you and I are in perfect agreement. For in that half hour of Wagner everything is in order and reaches a conclusion. And so, dear Maman, while you’re telling YOUR Albert: ‘Don’t listen to your brother, he’s luring you away from your proper (musical) path.’—for Albert will have received my letter from Cap-Martin—make a new listing for your son on the first page of the New Year: ‘architect-sculptor-swimmer-diver,’ fundamentally a musician par excellence and inventor of the Modulor, that eminently musical creation. And moving on to the circumstantial kisses.” Le Corbusier signed off, “To Dear Maman, young as she is with her magnificent smile, all our best wishes, our affection, our admiration, our gratitude. And thanks too for all the wonderful nourishment you managed to get inside us all along.”22 How clear it was: a Wagnerian duo, an orgasm, him and his mother.

It was the height of Le Corbusier’s career: Chandigarh was proceeding at a clip, applause was still reverberating for Marseille, Ronchamp was nearly complete, and there were projects galore in the office. Yet lying there in his fever delirium, he was still determined to achieve one further victory: the dethroning of Albert.

7

On October 7, 1953, Chandigarh was to have its opening ceremony. Two and a half weeks prior to that event, Le Corbusier prepared a letter in English for Nehru.

Your Excellency and Friend,

I think you should be acquainted on the day of the Opening Ceremony of Chandigarh—a halcyon day full of lightheartedness—of the sad financial plight of your Architect, your Town Planner, Le Corbusier, the animating spirit of the town. He is in debt of several millions because:

1°) the Punjab Government had not yet payed [sic] him,

2°) his wealthy Ahmedabad clients (the Municipal Corporation, the Millowners’ Association and several private and very rich clients) have not yet payed [sic] him.

Since two years and ten months I have devoted nearly the whole of my activity to India thereby neglecting to undertake more profitable surveys. Despite all my efforts I have not yet succeeded in being paid. Who is the real responsible? Since June last, my Creditors have become exacting and I have been obliged to leave off paying my draftmen in my architectural office. At 66 [sic] years of age I have never been in such a desperate financial plight.

Meanwhile, all over the world, the public opinion praises Chandigarh, India and the Indians.

I will say no more. My grief is immeasurable. I hope this letter will be handed over to you on October 7th.

I remain,

ever your most truly,

LE CORBUSIER

P.S. Repeatedly Chandigarh has asked me to send innumerable plans for the Governor’s House, the Assembly, the Capitol Park and the National Park, the Monument, etc. How am I supposed to pay my draftmen?23

WHEN THE CITY of Chandigarh was inaugurated on the day after Le Corbusier’s birthday, the press called it “The hour of Le Corbusier,” but the architect himself was not present.24 He probably could not have paid the airfare.

There were other reasons as well not to travel. Le Corbusier was suffering from rheumatism in both ankles, especially the left one, because of decalcification. He enjoyed the cure—eating masses of meat—but there was no clear course of action for Yvonne, whose right knee was terribly swollen. Her diagnoses included decalcification worse than his own, fluid retention, and other causes, with the doctors still submitting her to endless X-rays and testing. Of course, the main problem was that she kept falling down drunk.

In addition, she was anorexic. Le Corbusier wrote his mother, “She can’t eat because of some obsession or psychysm or other.” Deeply upset as he tried to figure out how to get nourishment into her, he admitted to Marie Jeanneret, “It’s extremely depressing to see this splendid girl chained to the unknown.”25

His mother, on the other hand, was his solace, the equal of the greatest force in the universe. “You’re my sun,” he wrote her.26

8

A month after the inauguration of Chandigarh, Prime Minister Nehru laid the foundation stone of the new Secretariat. Again Le Corbusier was absent from an event he should have attended.

Nonetheless, the prime minister’s presence gave incomparable glory to the architectural milestone. Nehru landed at 8:30 a.m. by jet at the Ambala airfield, near the new city. Some twenty-five thousand people greeted him. At the ceremony, Nehru emphasized the need for peace between India and Pakistan. Lamenting a recent incident in Calcutta when “some unknown person foolishly…fired at the building of the office of the Deputy High Commission of Pakistan,” he declared the future Secretariat a symbol of peace and unity.27

The prime minister was also determined to counter the strong criticism uttered in many precincts about Le Corbusier’s architecture: “A city without a soul would be a heap of mud and mortar…. A city built must have a soul and provide a spirit to its inhabitants based on our old traditions.” Attacking “the few cities built by the British Rulers in their days for their own convenience,” Nehru urged the public to be open to a new style, admirable because of its lack of reference to European tradition, and to recognize that the residential bungalows to which they had become accustomed had been designed to suit the colonialists rather than the Indians.

It was as if the absent Le Corbusier had written the prime minister’s lines. Nehru continued, “Probably one who is accustomed to looking at ugly things is not accustomed to objects of beauty.” It was the spirit of L’Esprit Nouveau come to life. At last a person of far-reaching power echoed the precepts of Ruskin and disparaged weak traditionalism as vociferously as Le Corbusier: “The houses built by a particular type of rich people…were more marked by their vulgarity than by anything of taste.” By contrast, “the foreign architects” who had designed Chandigarh “get full praise from the Prime Minister.” He told the audience that, for the first time, the foreign press, especially in Europe and America, was heaping compliments on modern architecture in India, saying that Chandigarh should be a model for cities all over the world. It was a great source of pride—the opposite of Calcutta and Kanpur with their huge skyscrapers overpowering “the hovels in which the poor laborers live there.”

This architecture in which everyone was to be housed decently was part of a new social order. Its ultimate goal was the disappearance of the caste system, under which the servant class had previously been relegated to inadequate accommodations. The prime minister assured his audience that this new Secretariat, planned so that it would take only forty-five seconds to go to the highest story in spite of the enormousness of the structure, would be the symbol and embodiment of this revolutionary equality.

The Ambala Sunday Tribune reported that, accompanied by his daughter, Indira Gandhi, “the Prime Minister was in a very bright and jovial mood throughout.” A group of girls from a local school sang the “Jana Gana Mana.” After laying the cornerstone, which was positioned by electrical machinery, “he jumped up to the dais to take back the baton which he had forgotten to carry with him when he went to press the electric button which lowered down the simple and sober bronze plaque bearing Pt. Nehru’s name in the socket below.” With the Punjab governor, Indira Gandhi, and Varma, the great leader toured the new city in an open truck and “ascended to the top of the club building in Sector twenty-two to have a clearer view of the houses built around.”

In Paris, Le Corbusier read the newspaper account eagerly. On his carefully cut-and-pasted clipping, he circled one key sentence: “‘The old methods do not suit the new age of Democracy,’ said the Prime Minister.”28 At last, Le Corbusier was understood.

9

The opening of Le Corbusier’s major exhibition of his work at Le Musée d’Art Moderne of Paris, in the eastern wing of the Palais de Tokyo, in November 1953 was for him one of the most significant moments of his life. The Palais de Tokyo was only a few blocks from the Perret brothers’ offices, where Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had shown up forty-five years earlier as a hesitant young man with the portfolio of Italian sketches that landed him his first job. It had models and photos and plans of Le Corbusier’s architecture, as well as drawings, paintings, sculpture, books, houses, and urban plans. It presented the full body of Le Corbusier’s work as a unified entity.

Le Corbusier believed this presentation demonstrated “a single and constant created manifestation devoted to various forms of the visual phenomenon.”29 The initial reaction was, however, a stinging disappointment. The architect’s own account of the opening took to a dramatic peak the pain he invariably felt when snubbed. Now more than ever, he saw himself as an exile and castaway—and the people in power as evil incarnate. He wrote in his diary, “November 17th, 1953. Paris: Opening of the Le Corbusier Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. 11 o’clock, official visits. 3 o’clock, journalists. 9 o’clock, invited guests…11:45, 11:30, 12…Minister of Education and Minister of Fine Arts, Secretary of State for Fine Arts, Director-General of Arts and Letters, Director-General of Architecture…all absent. When telephoned, one is busy with the budget, another can’t make it, the others the same. These are the four leaders of the arts in France. The Le Corbusier exhibition is an important event, properly scheduled. I sent out invitations to the dinner myself. They don’t come. I’m not the loser. The game was played correctly. According to the rules. If they’re satisfied, so are we—even more so.”30

His mother and brother also had failed to show up for the opening events. Le Corbusier wrote them to emphasize only what they missed, not the other absences. Between two and three thousand people had attended the opening, he told them. It had become necessary to organize, on the spot, a system whereby the crowd went through the show in an orderly progression. It was so mobbed that it was impossible to see the art.

“Enthusiasm and anger,” Le Corbusier wrote his family about the public response.31 The critics had unanimously tried to outdo each other in nastiness, while the attendance broke records. Three hundred and fifty visitors had gone through on the first Saturday, 620 the next day. During a recent Léger show at the same museum, there had been 1,700 in all, 1,200 at a Klee exhibition; his totals would be far larger, and 12,000 visitors had walked through an exhibition of his work in Stockholm. The officials and his family had ignored him; the journalists had slammed him; but the numbers were on his side.

10

The continual financial problems in India and the boycotting of his Paris opening were not all that was plaguing Le Corbusier. Yvonne had become so difficult that he could no longer resist confiding to his mother and Albert. At the end of November, he wrote them, “Yvonne wavers between confidence and rebellion. She has a damn hard little head. But she obeys—secretly—all our orders and suggestions.”32 Le Corbusier went on his own to Vevey for Christmas with “M. et Mme. Jeanneret.” Then he doubled back to Paris to take Yvonne to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin for New Year’s.

The weather was bitter cold, and Le Corbusier had a relapse of his pneumonia, requiring penicillin. Then Yvonne broke her right leg in another drinking binge. The injury was complicated, with fractures in three places, including a broken tibia. She was put in a cumbersome cast that made the return to Paris exceptionally difficult. When the architect went back to Chandigarh at the end of January, his own energy was depleted. He wrote his mother, “My health suddenly improves and I gain weight in just a few days, then everything collapses with the heavy burden of events.”33

Le Corbusier arrived in Delhi in a storm, with heavy rain and surprising cold. On his first few days in Chandigarh, he suffered repeated nightmares. But his spirits quickly revived. He was impressed with what Pierre had achieved, both architecturally and diplomatically, and was delighted with the quality of the concrete used in his various buildings. Le Corbusier also enjoyed the feeling of being “respected and considered and accommodated”—words he delighted in spelling out to his mother.34 He spent an hour with Nehru in New Delhi and felt that the meeting served to make the governor of Punjab that much more amenable to his ideas. There was no further reference to his fee.

From India, Le Corbusier wrote his mother that he had decided that his wife’s main problem was malnutrition. She was “completely decalcified”—to such an extent that he used his most gruesome adjective yet: “Buchenwaldized.”35 But he also reminded his mother of why he had married Yvonne to begin with. Her good spirit, intrepidity, and simple kindness were what had lured him, and they counted still.

He begged his mother to recognize that he had done everything possible to help his wife—even if he had failed. “So I scolded, organized gastronomic events, and exerted moral pressure at every moment, on this child that she is, who ended by ‘psychologizing’ herself in reverse.”36 It was another battle Le Corbusier could not win.

11

After two weeks in Chandigarh, Le Corbusier went south to Bombay for three days. While he was there, the largest Bombay newspaper published a piece by a reporter who had visited his site at Marseille. The residents had said that because of the sunscreens they froze in the winter and died of the heat in the summer. The journalist predicted that the use of the brises-soleil in Chandigarh would be a disaster.

By now, Le Corbusier was accustomed to this sort of criticism. This time, though, a head of state was on his side. The money problems about which he had written Nehru did not matter as much as the prime minister’s strength in dispelling the usual forces arrayed against him. Le Corbusier had found his place in the world.

The journey back to Paris at the end of February took twenty-six-and-a-half hours, but it was comfortable. “Nothing is more ideal than the airplane. I usually get a real joy from flying,” he wrote his mother and brother.37

Yvonne’s state upon his return was worrisome, though. She was not able to greet him at the airport as usual. The day after his arrival, he wrote his mother and Albert, “She is a lot thinner, living like a recluse far from daylight, fresh air, and sunshine. Her husband, as you know, is the man who discovered SUN, SPACE, GREENERY, the raw materials of urbanism.”38

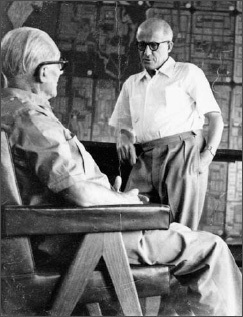

With Pierre Jeanneret in Chandigarh, shortly after they were reunited following the schism that occurred between them during and following World War II

WHEN AUGUSTE PERRET died just after his return, Le Corbusier was asked to speak at his former mentor’s funeral. In public, he was appropriate; to his mother, he was blunt about yet another of the people he had once deified but had come to loathe: “Perret was a violent adversary, neither pleasant nor correct. I tore him out of my heart long ago.”39

Le Corbusier’s personal worries were mounting. Yvonne was out of her cast but now required an apparatus to keep her leg straight. That spring, his mother had bronchitis and needed to stay in a nursing home. He assumed all the costs, but, given her age, her condition was a real concern.

Professionally, however, he was at a high. Le Corbusier was completing one major project after another. He was very pleased with the quality of construction in Nantes and with the helpful role of Claudius-Petit. Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry left India in the middle of the year, leaving Pierre in charge, which suited Le Corbusier; it enabled him and Pierre to work, unencumbered, toward the opening of the High Court in November. Even if India was now three years in arrears on his architectural fees, he had come a long way from the errant son who depleted his parents’ life savings.