XLIX

1

At the start of March, his mother fell in an accident caused by her cat. Le Corbusier did not, however, go to Vevey, since on March 15 he had to leave for Chandigarh for the inauguration of the High Court. This was one ceremony in India he could not miss. Having initially telegraphed to say that he would not be attending unless the many millions that had now been owed him for fourteen months were received before the event, he made the journey.

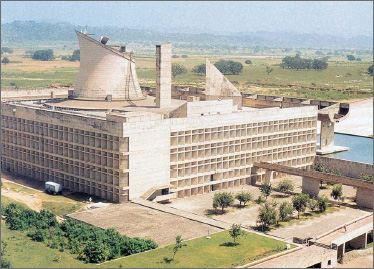

PRIME MINISTER NEHRU once again presided. Almost the entire population of the new city turned out to greet the popular leader as he arrived from New Delhi, with thousands of children lining his route for nearly two miles and waving multicolored flags. Once Nehru was in front of the new building, Le Corbusier made a speech linking his architecture with social change and defending his designs for Chandigarh against their critics, who, he told his audience, were too cowardly to accept progress. Then two thousand visitors watched as Nehru “pressed an electric button and the doors of all the court rooms opened automatically” to reveal Le Corbusier’s tapestries and his and Pierre’s furniture.1

The building was the first monumental structure completed in the controversial new city. The Indian papers referred to the roof of the structure as an “inverted umbrella” and its overall appearance as “cold and rugged.”2 But what was at first startling to wary journalists and a skeptical public was given a rare boost by having the public endorsement of a beloved leader, and soon enough the building’s intrinsic splendor helped dissipate the initial resistance to its many surprises. The unprecedented composition of rough concrete quickly assumed the status of a monument of modern architecture.

THE HIGH COURT encourages faith in government and the possibility of true justice. Authoritarian without being arrogant, this completely original building has a nobility of form and emanates a wonderful energy and optimism.

When you first see it, from afar, it draws you in, like a magnetic force, the way the Gothic spires of Chartres summon you nearer. Part of that pull comes from color. While it was under construction, Le Corbusier asked everyone with whom he was working if they should put color on the three great columns. Without exception, the other architects and engineers said no, the forms themselves had such majesty that the addition of hue would be an unnecessary distraction. Le Corbusier listened attentively. Nonetheless, day after day, he continued to pose the same question. The negative response was unvarying. Then he went ahead and had the colors of the Indian flag applied to the columns anyway.

Le Corbusier may have initiated the consultation in earnest, convincing himself that he cared about what the others would say. But his decision making came, as always, from within himself and from some vague source of inspiration. It was as if his art happened to him, and he was merely the agent. In that vein, once he had received the impetus and executed its directives, he was unequivocal; as M. S. Sharma pointed out, this was the same person who said of his paintings, “If you like them, very nice. If you don’t, forget it.”3

The columns are painted, from left to right, in vibrant pastel tones of green, yellow, and salmon pink. As you face these pillars and look up, generous amounts of blue sky come through wide openings between the building and its roof, which is like a flapping canopy, so that the blue, too, becomes an element. To the left and right as well, color is everywhere—showing up through further openings and the windows—and is always changing and surprising you. But for all that fury of hues and forms and sense of reckless abandon, the columns support the roof with impressive strength and muscular grace. The color is not overkill; rather, it gives music to the concrete. In the bright sunlight, the green, yellow, and salmon are as bold in spirit as the robust cylinders they cover.

The three entrance columns have the lasting power of a force of nature, like a mountain peak or a giant waterfall. Yet they declare themselves as having been constructed by man. Those great stiltlike legs are monumental in the same way as the buttresses of Notre-Dame, manifesting their builder’s capability. The High Court at Chandigarh is different in scale and purpose from the cathedral, but like that great edifice, it has both a grandeur and the quality of not diminishing the viewer. Like Notre-Dame, Le Corbusier’s court makes you feel tall and strong; its radiant energy enters you.

The fenestration of the High Court is one of Le Corbusier’s finest abstract compositions, precisely orchestrated to suggest randomness and improvisation. The well-organized complex network of interior ramps that lead visitors to courtrooms and offices is equally dynamic. In its framework, it is comparable to the human skeleton; in its ongoing motion, it resembles the human circulatory system—the miraculousness of which Le Corbusier was particularly aware, having sketched the varicose veins that had only recently been removed from his own body. Nature, after all, is the greatest architect ever.

2

Most photographs show the High Court brand-new. In those images, it might as well be a building model, rather than the living and breathing entity it has since become. For a virtual village has developed at its feet, and the building itself has acquired signs of age and use.

As a sculptural object, the High Court is a fine amalgam of forms, with rhythmically charged verticals and horizontals and a perfect balance of small and large elements. But half a century or so after its completion, while it remains a virtuoso visual performance, it is richer still. For not only does the High Court connect harmoniously to the plateau that surrounds it and to the distant mountains, and relate to the adjacent buildings in view, but it also interacts with the people perpetually entering and leaving it.

As you approach the looming structure, you walk amid women in brightly colored saris, many of them sitting on the ground and selling peanuts; half-clad children milling about; old men stooped on walking sticks; and judges and lawyers and their clients pacing purposefully toward the courtrooms. You hear the composite sounds of the assembly of people, and the justices in their black robes speaking both Hindi and Punjabi.

The High Court seems to succor them. All these unexpected elements—the people selling their wares, the piles of faded legal documents visible in the windows of the offices and courtrooms—are at home in Le Corbusier’s creation, rather than intrusive on a pristine design. The building is a setting for justice and life-altering decisions in the same way that a Gothic cathedral is a vehicle for religion and faith.

IN JANUARY 2000, the building entrance was partially obliterated by all the cars of Indian officials parked in front. The interior was appallingly filthy and decrepit. There was a distinct lack of maintenance—apparent in dirt, crumbling plaster, faded paint, and, on the roof, a pile of discarded tires and inner tubes.

But for all that, what force! And what a new way of thinking about the role of justice and the ability of color and form to add confidence and joy to the minute-to-minute experience of human beings.

3

Inside the High Court, there is a tapestry designed by Le Corbusier that is 144 square meters. It was woven over a period of five months by the men in Kashmir who had also made the 64-square-meter tapestries he designed for each of the eight smaller courts. The woolen hangings absorb noise, mitigating the resonance of the reinforced concrete and making the acoustics comfortable. They also give energy to the judicial proceedings. Bright abstract forms play against somber ones, while depictions of lightning, sun, clouds, and stars are present. Like work by Kandinsky and Miró, to which they refer, the tapestries evoke the entire universe.

Shortly after the High Court was put into use, Le Corbusier heard from Pierre Jeanneret that some of the justices had removed his tapestries from their courtrooms. The chief justice, however, had kept his, and was enthusiastic about it.

Le Corbusier wrote to Nehru. He began by obsequiously heaping gratitude on the prime minister for the commission of the new capital. Then he got to the point. He asked how these “subalterns” could possibly have the right to make such a decision. What gave them the temerity to countermand the taste of the person who, because of Chandigarh, had become “the first architect of today’s world?” While apologizing for his conceit—“a thousand pardons for the lack of modesty”—Le Corbusier said he would not tolerate the maneuver.4

Subsequent details are lost to history, but the tapestries are back in place.

4

Balkrishna Doshi had a particular perspective on this building, starting with its political implications: “His bow to democracy lay in not placing his buildings on a pedestal—both the Assembly and the High Court do not have flights of steps. They’re not imposing that way. He put them on the ground—perhaps he didn’t want to change the level, he felt that in a democracy you do not put buildings on platforms.”5

Of the billowing roofline of the High Court, Doshi observed, “As always, silhouette was important for him. You see these shapes, almost like an umbrella, but look at the negative space and it’s like a dome…so he had this play of positive-negative, of floating form against the light.”6 Doshi recognized that the reason for this form was that it was essential for Le Corbusier that the sky actively penetrate his buildings. Earlier, this had been through geometric vistas, as in the Villa Savoye; now it was through a more organic interaction.

This desire for a connection between solid structure and the amorphous gases surrounding the earth was not always easy to realize. While Le Corbusier intended the shells in the High Court to be very thin (like the roof he was concurrently designing for Ronchamp), the realities of engineering did not permit this. They had to be redesigned as a heavier slab that in turn was curved and cantilevered.

The architect also had, yet again, a problem with the realities of the climate. His mother’s and Hélène de Mandrot’s leaking roofs and windows represented a difficulty that was endemic to his work. At Chandigarh, the beating rain during the season of heavy showers made it necessary to build an arcade in the High Court that had nothing to do with Le Corbusier’s original plans. His accommodation to the rain at the Millowners’ Building had been a rarity.

The roof constructions and the arcades were not the only instances of Le Corbusier’s idealism and aesthetics obliterating practicality or a full concern for the client’s needs. Doshi also witnessed the judges’ displeasure because, in spite of the architect’s intention to work with the local culture and Nehru’s praise of him for having done so, the High Court did not function according to Indian tradition: the courtrooms were too public. It was “a building that doesn’t work.”7 Modifications were necessary.

But Balkrishna Doshi still thought it was “magnificent.” The High Court had two sides, just as Le Corbusier did. The building design turned its back to certain truths and was wide-open to others.

5

Balkrishna Doshi was one of Le Corbusier’s favorite young architects and was accorded the exceptional treatment that went with that position. He was invited to lunch when others were not, and he and Le Corbusier took long walks together, during which the older man liked to tell stories. Le Corbusier sent his young colleague to a doctor when he needed one and helped him get a fellowship from the Graham Foundation.

When Le Corbusier gave Doshi and his bride a drawing as a wedding present and Doshi did not look sufficiently pleased, Le Corbusier immediately took it back. That evening, he went to Doshi’s house for dinner. In addition to another drawing, he gave the young man five hundred rupees. On the envelope, Le Corbusier wrote, “This is a small token to add grease to the wheels of life. I’m sure you will break many dishes on each other’s heads but you’ll survive all that with joy and pleasure.”8

Le Corbusier interacted with people according to his own terms. Doshi was present at a party in Chandigarh at which Le Corbusier conspicuously refused to shake hands with the judges and said, “You don’t dispense proper justice.”9 Sometimes he acceded to his whims; at other moments, he strategized. He cautioned Doshi never to send all the photos of a building model to a client; one was enough. It would give the client some idea of the proposal but would help avoid sources of disagreement. Similarly, Le Corbusier advised Doshi to let the client pick a single color to be used in a house but then to save the other choices for himself. That way, the client would feel he had made a decision and would thus be kept happy, but the architect would maintain control of the quality.

THE YOUNGER MAN was as impressed by Le Corbusier’s adaptability as by his craftiness. Le Corbusier also had a remarkable ability to improvise. If, in India, contractors had only two of the three sizes of stone that he had designated, he would have them cut one of the two existing sizes to make the third—all corresponding to the Modulor—and then, with characteristic frugality, would use the residue in floors or window panels or sunscreens.

6

Balkrishna Doshi also saw Le Corbusier at his most humane: “He gave the ordinary man dignity. It was as if he were looking at men and God together—no human being was really ordinary. Since he was not involved in politics or economics, he tried to give man dignity through his dwelling.” Le Corbusier used scale so that “no man felt less than a king in his house.”10

Photo Insert Two

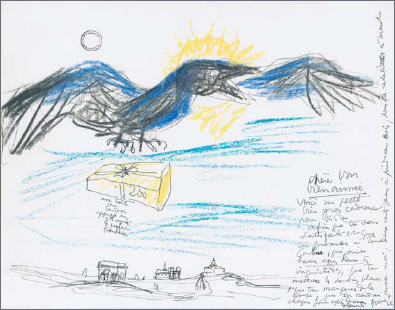

15. Self-portrait as a crow delivering Christmas presents, in a letter to Yvonne, December 1953

16. Sketch in a letter to his mother and Albert, August 31, 1955

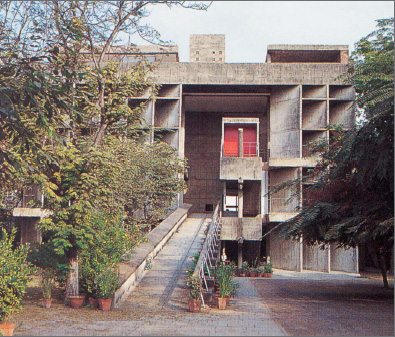

17. Entrance facade of the Millowners’ Building (1951–1956), Ahmedabad

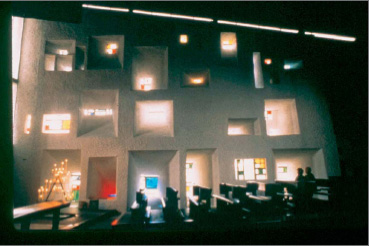

18. Ronchamp, interior, view from the altar

19. Ronchamp, interior, wall of painted glass windows

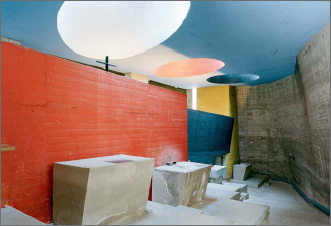

20. Interior of chapel at La Tourette

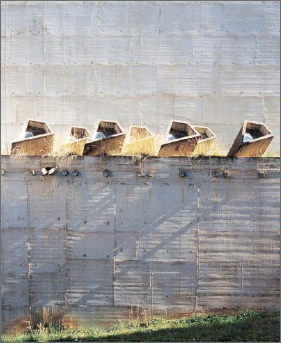

21. The light cannons at La Tourette as seen from above

22. The Assembly Building in Chandigarh, late 1950s

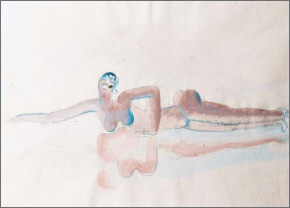

23. Josephine Baker, watercolor, 1929

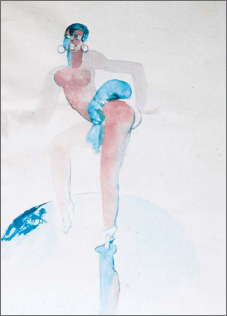

24. Josephine Baker, watercolor

25. Josephine Baker, watercolor

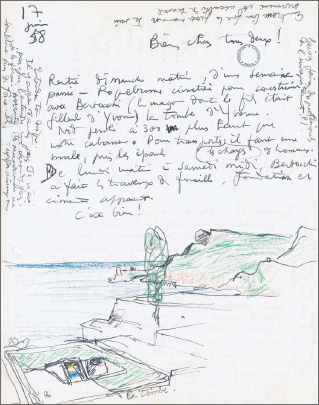

26. Sketch of Yvonne’s tomb in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, in a letter to his mother, June 17, 1958

Doshi was struck by Le Corbusier’s fascination with steamship cabins, train berths, and the shacks that poor people lived in. These small-scale spaces reflected very different economic means but had in common that they were composed of tight, shipshape units. When Doshi took the Swiss to see old six-foot-wide shacks in the slums of Ahmedabad, rather than recoil in horror Le Corbusier stretched out his arms in admiration. “My God, look how these people can live,” he declared, more with respect for their ingenuity in dire circumstances than sadness at their paucity of resources.11

Le Corbusier was so interested in sensuous experience in India that when eating meat he put big pieces of salt on some of the food and none on other pieces. “It seemed as though he always wanted two dimensions—thin and thick, tall and low, rough and smooth, light and shade. There was always this kind of counterbalance,” wrote Doshi.12 Such attention to the details of life and the will to alter its components were part of the refinement of his vision.

Often comparing his work to a fugue by Bach, Le Corbusier understood that change and difference, jumps in scale inside and outside, alteration of thick and thin lines, and variables of rhythm and balance are what make things work.

AFTER A WHILE, Doshi felt so resented by others as the master’s pet in Chandigarh that he got himself sent to Ahmedabad, where he replaced Jean Véret, one of the main architects in the Paris office, as Le Corbusier’s chief site architect.

There, Doshi saw Le Corbusier’s musical sense of composition at work as they were detailing the private house that Le Corbusier made for Surottam Hutheesing. Le Corbusier was displeased because he felt that the pattern was too rigid. Doshi proposed using rectangular columns instead of round ones: squared-off columns could serve as walls and storage spaces as well. Le Corbusier liked the idea and ran with it: “Within two hours he had made a miracle out of the sections by just adding a little beam here and a slab across and putting a circle there to open it up.”13 He had interjected the rhythm that brought it to life.

This exquisite villa—which Hutheesing sold to another mill owner, Shyamubhai Shodhan, before it was completed—demonstrates the results of Le Corbusier’s flexibility. A wonderful rough concrete shell with multiple openings and terraces, it includes a spectacular hanging garden. Inside, with its surprising juxtapositions of scale and unpredictable twists and turns, complete with staircases that seem to float in midair, it looks like a composition by Piranesi. Outside, the Villa Shodhan is a particularly luxurious Corbusean statement, with its ambient rough concrete punctuated by boldly painted, sparkling yellow and green panels, and its large, round swimming pool, with bright-orange ladders around the concrete perimeter, blending industrial toughness with a euphoric approach to color.

BEFORE HE LEFT INDIA for the last time, Le Corbusier invited Doshi to select another drawing for himself. The young acolyte made his selection, and Le Corbusier told him that he had picked the right one, so now he should pick another, and the process went on until he was given four in all.

That generosity was in the same proportion as Le Corbusier’s acidic toughness. Doshi accepted the apparent contradictions or inconsistencies as balanced sides of the same person. Once, when Le Corbusier was going to travel by car from Chandigarh to New Delhi and Doshi asked him for a ride, the older man gruffly replied, “No. No. No.” He then immediately said that if Doshi really wanted to go along, he could of course do so, if he was punctual. They were leaving at 6:30 the following morning. Doshi was there at the appointed hour, and Le Corbusier treated him as a cherished traveling companion for the next several days.

First, he insisted that they stop en route in the village that had his favorite restaurant for Tandoori chicken. Le Corbusier emphasized that he loved it because this was a true “mountain chicken,” tough muscled, more flavorful and full of character than a city chicken. In Delhi itself, Le Corbusier was equally definitive about everything he saw. He spent a lot of time studying Indian miniatures in the museums; he loved their intertwined figures. On the other hand, he thought Edwin Lutyens’s much-touted British colonial architecture was merely “okay.”

“The sense of eternity was very important to him,” wrote Doshi. “Counterbalance. Uncertainties. Conflicts. The dialogue that goes on within one’s self. The battle between one’s self and black paper. Some force is coming—the light. The idea of a pact with nature. A building and nature must merge.”14