LI

1

During one of his visits to the Sarabhais, Le Corbusier was on his way one morning to the local airport when he saw the vast power station of the Ahmedabad Electricity Company. Its monumental cooling tower had the form of a grain silo but with all the surfaces curved and stretched. Le Corbusier was riveted by the gigantic elastic structure. He was just then developing the General Assembly at Chandigarh, and he imagined how this shape might be applied to the entirely different domain of civic architecture. He immediately began sketching.

Anand Sarabhai was in the car that morning. The architect’s unique ability to see what others would fail to notice, and the fancifulness that accompanied his perceptiveness, were striking to the boy. At the airport, where there was a tiny restaurant, Le Corbusier fixated on the orange and green of the plastic salt and pepper shakers, moving them back and forth like chess pieces, staring at them. Everywhere he looked, color and form affected him.

In little time, a short, seemingly open-topped structure—concave around its entire surface and resembling the cooling tower—rose from the roof of the General Assembly. The base of the assembly is a Corbusean rectangular block, a lively amalgam of pilotis, brises-soleil, and exterior spiral stairs. The anomalous form emerging victoriously from its flat roof, serving as its main auditorium, the meeting place of the Punjab Senate, has the triumphant energy of birth itself. It was a public space entirely without precedent (see color plate 22).

Le Corbusier had utilized not only the appearance but also the structural properties of cooling towers. He had visited such structures at night, when he could observe them freely, and spent considerable time checking their acoustics, sometimes banging two wooden planks together to hear the echoes. He then applied the principles of these industrial forms to the hyperbolic shell of the assembly, which is consistently one meter and fifteen centimeters thick.

That sheath has been molded in a form that maintains its tensile strength. At its top, the tower culminates in an oblique, angled section—as opposed to a flat, horizontal roof. That unusual roof is buttressed by an aluminum framework that is—Le Corbusier delighted in providing the explanation—“a veritable physics laboratory destined to deal with the play of natural light and with a degree of artificial light, with ventilation, with the electronic-acoustic machinery.”1 This “laboratory” was a rational and orderly structure intended not to impose an impossible order on the natural havoc of life but, rather, to serve and honor complexity.

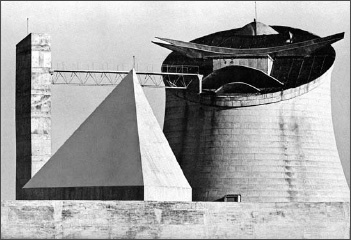

The roof of the Assembly Building in Chandigarh, late 1950s

“Furthermore, this cork will lend itself to future solar festivities, reminding men once a year that they are children of the sun (a fact entirely forgotten by our extravagant civilization, crushed as it is by absurdities, particularly with regard to its architecture and its urbanism),” he wrote.2 The juxtaposition, in a single sentence, of all-consuming sun worship with the absurdities of a civilization deprived of its instincts reveals the simultaneous hope and tragedy inside the perpetual cacophony of Le Corbusier’s mind.

The interior of the hyperbolic cylinder of the Assembly has thrilling physical properties. Part of it reflects sound, another part absorbs it, to allow for ideal acoustics on ground level when the deputies meet. The shape serves the purposes of air-conditioning by allowing cool air to enter several meters above the level of human congress and descend to breathing level, while the warmer air rises to the level of a mechanical apparatus that removes it. The form that, from the outside, is startling and discomfiting, is, within, accommodating and succoring.

The cooling tower also gave Le Corbusier a chance to link architecture with the reigning political philosophy. Nehru had established “a five-year plan whose primary aim was to develop industry and produce electricity on a large scale. Thus, the cooling towers of an electric power plant must have seemed to Le Corbusier a particularly appropriate symbol for expressing the social and political aspirations of this friend and patron…. Gandhi’s philosophy of rejecting technology and focusing on the importance of agriculture, handicraft, and cottage industry finds many direct and indirect references in the Assembly. The hand-made quality of the béton brut, the folk imagery on the ceremonial gateway, the wall decorations based on imprints made by the workmen, and the juxtaposition of the oxcart with the building in one of Le Corbusier’s sketches all attest to a world view that shared a great deal with Gandhi’s own. For Le Corbusier, Gandhi’s philosophy of rural rejuvenation offered a felicitous balance to Nehru’s technological bias.”3

The Assembly Building in Chandigarh, late 1950s

Le Corbusier saw himself as possessed of the power to understand the validity of such overarching ideas even more clearly than world leaders like Gandhi and Nehru did: “Life has placed me in the position of an observer, giving me incomparable—and exceptional—means of judgment. I believe that this order of thought is not available to political leaders and that they live in the problem and hence do not see it.”4 He believed that his architecture, more than the ideas of any world leader, whatever his or her philosophy, was the salvation of humanity.

2

Because of security regulations put into effect after a bomb in front of the nearby Secretariat killed sixteen people in 1995, it is now difficult for laypeople to obtain permission to go inside the General Assembly. If as a tourist you do manage to get in, you must carry nothing and empty your pockets completely; you are not even permitted to have a paper and pencil in hand. The absence of a camera or note-taking capability has its benefits, for you concentrate on an unforgettable unfolding of events. You do nothing other than look and absorb the sequence of astonishing experiences.

From the vast entry hall bathed in cathedral-like light, you proceed through a wide corridor that feels like a promenade, a glade in a forest: man-made architecture that conjures very tall trees with sunlight filtering through the foliage above. This space, which Le Corbusier planned for deputies to pass one another and meet for informal conversation en route to or from their assembly hall, encircles you in quietude and calm.

Then you enter the great meeting room. At first, it is frightening, like a weird cave. A visitor from the west could well wonder if this is suddenly the effects of the antimalaria medication or of the scorching Indian sun. The space is a hallucination. The ceiling soars in a myriad of directions. There are relief sculptures plastered onto its crazy ziggurat of forms that resemble shapes by Jean Arp animated and gone berserk. One cannot possibly fathom everything going on. Nothing has prepared you for the play of light and dark, the explosion of deep colors, the nonstop choreography of ostensibly inanimate materials.

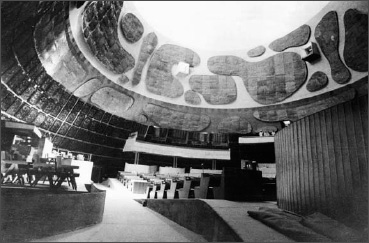

The Hall of Parliament in Chandigarh, late 1950s

You are used to art as seen in museums: paintings on the walls, sculpture in the round. This time, you are inside the work of art. If you can imagine being totally enveloped by one of the great abstractions of Wassily Kandinsky or Jackson Pollock, being surrounded by its elements as if it is a vast tent, you approximate the life force and energy of this auditorium. But you are also in a functional space, a meeting hall where rational decisions are made, a place where the acoustics and air-conditioning work efficiently. Tough events take place inside this work of art, and people engage in conversation, however disputatious, and exchange ideas. In spite of the taxing exigencies of politics and nationalism and the divisive religious differences that dominate discussions here, it is a setting where human beings achieve congress.

It has been reported that when the senate first tried to assemble in Le Corbusier’s new building, logical debate and productive communication were impossible. The architecture was too distracting, the effect on everyone’s mood too tumultuous. That disturbance is understandable. But once the politicians became habituated to the stimulus, dialogue flourished. Just as Le Corbusier had dreamed, a generosity of space, a spirit and energy in the physical surroundings, and a charge of visual rhythm were salubrious, infusing human beings with energy and opening their souls.

ARE WE INSIDE a vast human heart, having entered through an aorta into its throbbing chambers? This space, unlike any that has been made before, inscribed with unique forms, represents an apogee of imagination and courage. Standing at ground level with that whirlwind of shapes above us, we have no doubt that great art is at the edge of madness. The sheer unabashed courage evident in this hall, its Wagnerian emotionalism, the will to do what no one has ever done before are both wonderful and terrifying.

For all of his defeats and bitterness, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had never lost an iota of his youthful intensity. Here, encouraged and supported by Nehru, welcomed by a culture completely different from his own, he expressed all of his rapture. He gave from the same depths with which he responded. Now that he could let loose, everything flowed in a torrent, cacophonous yet coherent.

Le Corbusier managed, on his own, what few people would dare to consider: the expression of psychological complexity in tandem with the logic, precision, and practicality of the sharpest engineer. He found the means to construct a sound and functional being that represents havoc and clarity at the same time. He showed unstinting generosity in making happen for others everything that occurred inside his own fabulous imagination. No wonder the architect was so often arrogant or impatient. How could someone of such breadth be expected to tolerate academic stodginess, bureaucratic obstacles to life, bourgeois timidity?

Speaking of Le Corbusier’s Assembly, the architect Louis Kahn remarked to Balkrishna Doshi, “I have never met a man in my whole life who can freeze his decams.”5 That invented term suggested the power of a rotating cam multiplied by ten. To harness, encapsulate, and generate force was the miracle of this building.

3

Le Corbusier’s enormous office building—the Palace of the Ministries, known generally as the Secretariat—opened in Chandigarh in 1958, five years after Nehru had laid its foundation stone. Initially, the architect had hoped to make it a true skyscraper. The prototype was a structure he had designed for Algiers in 1942, which had not gone beyond the drawing board. That form had in turn led to the ideal secretariat he had designed for the United Nations, which had been kidnapped and disfigured. Le Corbusier hoped that Chandigarh would at last afford him the opportunity to realize his dream.

It was not to be. The engineers and Indian architects on-site told the architect that there was no local concrete strong enough to bear the vertical load of a skyscraper. So Le Corbusier simply turned the form on its side as a great horizontal slab. When the necessity for compromise had technical reasons, rather than being the result of human ignorance, no one could be more accommodating.

Again, one should not picture the building as it appears in many photos: as a purely aesthetic object gently doubled in size by its own reflection in the pond in front of it. The experience of the Secretariat is, rather, quite unsettling. To enter, one has to go through security checkpoints, facing a plethora of machine guns and rifles. Soldiers spit and belch while rejecting the credentials of most would-be visitors. And if photos suggest an orderly appearance to the grid of the facade, in actuality, up close, what is contained in that rectangular block is a frenzy of forms.

Yet there is a system to the madness; the surface and structure of this office building intended to serve three thousand employees is based on the Modulor. Issues of climate and sunlight are addressed by deep brises-soleil to provide shade, floor-to-ceiling window glass to permit maximum light, and narrow metal “aerators” with copper mosquito screens. The facade has rhythmic regularity, like the beat of the metronome atop his mother’s piano. It also depends on the mastery of materials and craft essential to his father’s livelihood, as well as the responsiveness to the sun and direct confrontation with the sky that marked the Sunday outings that were such a feature of family life.

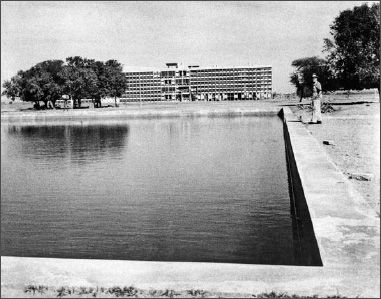

In front of the Secretariat and the High Court in Chandigarh in March 1958. Photo by Pierre Jeanneret

Balkrishna Doshi was witness to the process whereby Le Corbusier came up with the design of this building front. Initially, he had designed the Secretariat to have balconies that stretched across the entire facade. But these long spans were so heavy that they needed to be cantilevered and required supporting elements that were not part of the plan. The contractors and site architects could not figure out how to conceal the necessary armature. Doshi reports, “Everyone wondered where the solution lay, and a lot of work was put in. One fine morning Corbusier arrived at the site, took a look at what was happening and said, ‘No, no, no, not like that. Let the columns go straight down breaking the sun breakers. Don’t make changes in design. Just let them go through.’”6 As is often the case with easy solutions to complex problems, no one else had thought of this idea of keeping the armature visible.

These bold, continuous columns on the exterior of the building, blatantly there to provide support, had, Doshi observed, an aesthetic consequence as well: “The sun breakers changed and a totally new pattern emerged, most interesting and very beautiful because you never anticipated the strange rhythm that would occur. Le Corbusier was always able to give us the unexpected. In his desire to be formal he got into difficult situations in which there was no alternative but to land in a mess. But like an acrobat, he always managed to emerge unscathed.”7

Le Corbusier spoke about what he had done with the building’s circulation system in his most straightforward language: “The two large ramps in front of and behind the building, connected to each floor, are also made of raw concrete. They provide the three thousand employees an attractive means of circulation (morning and evening). The mechanical vertical means is provided by banks of elevators, in addition to a double staircase set in a vertical spine rising from the ground floor to the top of the structure.”8

Depending on whether employees arrived by foot, on their bicycles, or by bus, they approached the Secretariat from either the Boulevard of the Waters or the Valley of Leisure Activities. Amusing vestiges of his early romanticism, the terms reflect Le Corbusier’s attempts at poetry, which might have better suited a retirement community. In spite of those calm descriptives and the ordering role of the Modulor, the building itself is intensely animated. Both the southeast facade reflected in the water and the northeast side, which one approaches from the large area of land defined also by the High Court and the assembly, are highly charged.

Each facade is an amalgam of solid and void, of closed and open shapes. There are even more ins and outs and unexpected twists and turns than the Perret brothers’ building at 25 bis rue Franklin had had. These facades are completely asymmetrical, each as impossible to absorb or understand in full detail as the workings of a human mind, conjuring Kandinsky’s statement, “There is always an ‘and.’”9

4

The roof of the Secretariat is even livelier. The forms that rise out of the flat terrace atop the building resemble plants growing out of the sea bottom. Perhaps Le Corbusier was indirectly influenced by what he saw when he was swimming in shallow water along the Mediterranean coast. Or maybe, like the cloudlike reliefs floating around the ceiling of the Assembly, these organic shapes are simply the product of the architect’s imagination. Whatever the source, a Corbusean playground of forms teeters on madness. Antonio Gaudí’s Casa Milà and Church of the Sagrada Familia are among the few architectural equivalents to this multidimensional free-for-all.

As on the roof of l’Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, on top of the Secretariat Le Corbusier has put you under the hot sun, facing the mountains in one direction and flatness in the other. When you look from that roof in the direction of the General Assembly and the High Court, you see an architectural landscape unlike any other on this earth. But, oddly enough, the High Court, so thunderous up close, from here reads as a series of graceful arches, a bit like the calm and orderly facade of the first Renaissance building, Brunelleschi’s Hospital of the Innocents in Florence. The High Court is not governed by the same precise system of equals as the Brunelleschi, but a harmony and a sense of measure and logic prevail, thanks in part to the Modulor. With Le Corbusier, however, where there is order, there is also madness. You are surrounded by a lush frenzy on this eagle’s nest, and you face the assembly’s extraordinary tower—as well as the completely unusual monument to the Open Hand. One understands why Doshi was so struck by the architect as a man of counterbalances.

Today, on top of the Secretariat you might find tents or colorfully dressed bakers frying pastry balls. It is a floating village—like the roof at Marseille with its nursery school and playground, a place to be used, a gathering point where people can breathe good air. As always, Le Corbusier’s architectural machine accommodates endlessly varied living.

BALKRISHNA DOSHI does not dissemble about the flaws and shortcomings of the Secretariat: “Everyone knows of course that the Secretariat fails, fails totally, as an office building. It doesn’t take into consideration the requirements of an Indian office…. The people involved were over-awed by the fact that he was a genius and also a foreigner and therefore thought that nothing could go wrong; they were hesitant to discuss functional issues with him. He didn’t ask, they didn’t question, so the blame lies with both. Indians are generally too subservient to foreigners.”10

Charles Correa, another architect who built in India, points out other inherent problems, putting a very different slant on Le Corbusier’s beloved brises-soleil: “they are really great dust-catching, pigeon-infested contrivances, which gather heat all day and then radiate it back into the building at night, causing indescribable anguish to the occupants. They are not nearly as useful as old-fashioned verandahs, which are far cheaper to build, protect the building during the day, cool off quickly in the evenings, and, furthermore, double as circulation system. Neither have the great parasol roofs (as in the High Court) proved much more useful. Was LC perhaps more concerned with the visual expression of climate control than with its actual effectiveness? In any event, his enthusiasm seemed to lie not in solving the problem but in making the theatrical gesture—assuming the heroic pose—of addressing it.”11

To the architect Paul Rudolph, on the other hand, the Secretariat was an aesthetic wonder, whatever its flaws: “In every way it opposes the mountains; the angled stair way, the ramp on the roof…all these angles are obviously and carefully conceived to oppose the receding angles of the land masses.”12

Finally, there was the evaluation of Nehru: “It doesn’t really matter whether you like Chandigarh or whether you don’t like it. The fact of the matter is simply this: it had changed your lives.”13

5

The Governor’s Palace was never built, and the Open Hand rose only later, but most of Le Corbusier’s buildings, as well as his overall scheme for Chandigarh, had come into being as he intended. In March 1959, Prime Minister Nehru declared, “I have welcomed very greatly one experiment in India, Chandigarh. Many people argue about it, some like it, and some dislike it…. It hits you on the head, and makes you think. You may squirm at the impact but it has made you think and imbibe new ideas, and the one thing which India requires in many fields is being hit on the head so that it may think…. There is no doubt that Le Corbusier is a man with a powerful and creative type of mind. For that reason, he may produce extravagances occasionally but it is better to be extravagant than to be a person with no mind at all.”14 Because Nehru considered the architect a demigod in his lifetime, appreciating and supporting his creativity—even if he did not construct the Open Hand—Le Corbusier had blossomed and made some of his finest architecture.

Almost everyone living in Chandigarh says the same sort of thing: “It is the best organized city in India.” “The nicest city to live in.” “We have family in Delhi, but could only live here.” “Things are near to each other and easy to find.”15 Its residents are glad to be there, and if outsiders see it as a down-at-the-heels, polluted, unkempt metropolis, Chandigarh still beckons with some of the most exhilarating buildings on earth.