LV

I improvised, crazed by the music…. Even my teeth and eyes burned with fever. Each time I leaped I seemed to touch the sky and when I regained earth it seemed to be mine alone.

—JOSEPHINE BAKER, ON HER PERFORMANCE WITH THE REVUE NÈGRE IN 1925

1

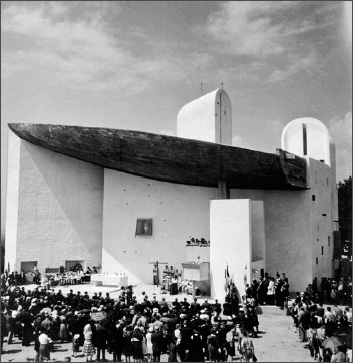

On June 25, 1955, when the chapel at Ronchamp opened to the public, the event was instantly recognized as a milestone in postwar cultural history. The time had come to be receptive to modernism—to endorse what was daring and untraditional—rather than to risk being guilty of committing the sin of the famous rejections that had thwarted Manet, van Gogh, and the Fauves in their heyday. However outraged the critics and public were in private, they had now learned to act respectfully. Reading Le Figaro’s coverage of the inauguration of “the chapel built by Le Corbusier” over its morning café au lait, the French public now knew the architect’s name as a household word that warranted respect.1

Under brilliant sunshine, the day’s events began at 8:30 a.m. at the local town hall, where Mayor Pheulpin made Le Corbusier an honorary citizen of the town of Ronchamp. From there, a cortege formed, headed by the local band, and proceeded to the monument to the dead. A spray of flowers was placed on the impressive pyramid of discarded stones. Previously, such monuments to victims of war tended to be figurative sculpture, often with Latin inscriptions. Now the crowd stood for a minute of silence before something that resembled a heap of rocks. What Le Corbusier had spontaneously erected on the chapel grounds was the perfect physical equivalent of that silence.

At 9:30, further dignitaries arrived in their official cars at the bottom of the steep path. They walked up and joined the rest of the assemblage in the chapel itself.

Le Corbusier had asked Edgard Varèse, the composer whose work he had admired in New York eight years earlier, to produce music that would somehow be recorded in a linear way—on a ribbon or wide thread—and could be cut into morsels by a music director during the opening. Varèse had declined. Some of the music performed during the inauguration was almost as modern—“Te Deum” by Marc-Antoine Charpentier; “Apparition de l’Eglise Eternelle, les enfants de Dieu, les Bergers, Jésus accepte la souffrance” by Olivier Messiaen; “Symphonie de Psaumes” by Igor Stravinsky—but there was also the traditional “Enveillez-vous” and “Grand Prélude” by Johann Sebastian Bach.

Alfred Canet, secretary of the real-estate company that had diligently overseen the development of this unusual project, publicly gave the new building to the archbishop of Besançon, Monseigneur Dubois. The Belfort newspaper reported: “An especially moving moment, for it was the workman on the land who offered his labor to the Lord and Master of all things.”2

The archbishop quoted Minister of Reconstruction Roger Duchet’s praise of the local authorities for having had “one of the masters of contemporary architecture” replace the destroyed sanctuary.3 Following that discourse, Eugène Claudius-Petit, General Touzet du Vigier—a member of the Force Française Libre (FFL) who had been a companion of De Gaulle’s in North Africa—and Le Corbusier himself could all be seen praying respectfully. No one seemed aware that the architect descended from the sort of Protestants who during the Reformation had pillaged the edifices of Roman Catholicism.

Further officials and dignitaries gave speeches emphasizing the tragedy that had befallen the previous chapel and affirmed the wish that the new structure would serve pilgrims as its predecessor had. Canet offered profuse thanks to “the leading architect of our time who, with an exceptional team, accomplished this work he holds so dear to his heart.” He ended by reciting the prayer that King Solomon had offered Almighty God on the day of the dedication of the Temple at Jerusalem: “Grant to all peoples who climb toward…this house we have built for You…in order to offer You prayers, and grant us Forgiveness, Justice and Peace.”4

Le Corbusier repeated the realtor’s gesture of publicly handing the building over to the archbishop. Man’s work was being given to the representative of God. He underlined the religiosity of the chapel and the way it conformed to aspects of a traditional ecclesiastical program, while pointing out its ability to serve nonpractitioners as well: “In building this chapel I wish to create a place of silence, of prayer, of peace, of inner joy. The sentiment of the sacred animated our effort. Certain things are sacred, others are not, whether or not they are religious.”5

The architect singled out Maisonnier and Savina—the two craftspeople with whom he had worked most closely—and praised all the other engineers, workers, and administrators who had figured out the mathematics and systems necessary for the construction of this complicated building.

Then, carefully, and with a brevity unusual for him, Le Corbusier specified the ways in which the chapel honored Catholic liturgical tradition: “Certain scattered signs…and certain written words express the praise of the Virgin. The cross—the true cross of torment—is installed within this ark: the Christian drama has henceforth taken possession of the site.”6

It was an occasion for him to be humble and unassuming. Yvonne, as a Catholic, would surely have been pleased. There was no way she could have made it up the footpath to the actual scene, but he would tell her about it. Addressing himself specifically to the archbishop, Le Corbusier concluded his remarks, “Excellency, I deliver to you this chapel of loyal concrete, built boldly perhaps, certainly with courage and the hope that it will find in you, as in those who climb the hill, an echo to what all of us have inscribed herein.”7

While the architect underlined the religiosity, the archbishop praised the modernism. Monseigneur Dubois called the chapel a “witness to the faith of new times.” It was as if he had boned up on Le Corbusier’s history and the goals with which Charles-Edouard Jeanneret and Amédée Ozenfant had launched L’Esprit Nouveau more than three decades earlier. The religious leader then declared, “Maître, you have performed an act of courage in creating such a work.”8 Dubois said that the new chapel honored the tradition of thirteenth-century cathedrals as “an act of optimism, a gesture of courage, a sign of pride, a proof of mastery.”9

Dubois pointed out that, three years earlier, Le Corbusier had told Claudius-Petit he had created l’Unité d’Habitation in Marseille “‘for men.’ Here, Monsieur, you have labored for a greater master: for God and for Our Lady. You feel this: the soul of the true ‘radiant city’ is here, on this hill.”10

For a cleric to be so knowledgeable about the architect’s work and intentions was unusual. His recognizing and publicly acknowledging the consistency and continuity of Le Corbusier’s life’s work and the extent of his dedication to the goal of making the world a better place was a small miracle on the holy site.

Mass was performed. The archbishop gave his benediction and “by special favor, grants an indulgence to those who have associated themselves with this benediction.”11

The crowd returned to the pyramid made from the stone of the destroyed chapel. It was then officially dedicated to the memory of those who died during the liberation of France. Two generals presided; the flags of the FFL were ceremoniously placed on the monument by a group of veterans. “General Touzet du Vigier evoked, with the simplicity and feeling of a great-hearted man, the harsh battles which took place on this hill and which this monument commemorates.” The general adjured, “Our Lady, take under protection those who died for France.” One must never forget “those who have given their lives so that there shall be no more division, hatred, and war.”12

A representative of a veterans’ organization offered sympathy to the families of the dead, and “The Marseillaise” was sung. Probably no one present realized that, while the dead people now being honored had been fighting France’s invaders, Le Corbusier had been working away in Vichy.

2

Light acquires a transcendental quality: it is not the light of the Mediterranean alone, it is something more, something unfathomable, something holy. Here the light penetrates directly to the soul, opens the doors and windows of the heart, makes one naked, exposed, isolated in a metaphysical bliss which makes everything clear without being known. No analysis can go on in this light: here the neurotic is either instantly healed or goes mad.

—HENRY MILLER, The Colossus of Maroussi

The morning that had started in bright sunshine turned torrid, and then the sky became stormy. But the weather cleared again, and a light breeze offered relief from the heat. Four hundred people were given lunch in a vast metal hangar erected nearby. Le Corbusier granted interviews to journalists. According to one account, “He rather disappointed us by the slightly ironic tone he gave to his answers…. Then he surprised us by these statements: ‘I have performed my little task…. If what I have done is understood (apropos of the motifs decorating the doors of the sanctuary) I have succeeded; if not, it is a failure; I have in my pocket a child’s drawing; I do not know what it is, but he surely knows.’”13

As people were finishing their lunch, the ceremonies ended with “the solemn salutation.” A number of those present had made the long journey because the following day, Sunday, was to be the official beginning of “the era of new pilgrimages,” one local newspaper reported. Almost everyone there was visibly moved by both the building and the words used to sanctify it. One local journalist referred to “the generosity of the faithful” that had made possible this sanctuary, “whose dazzling whiteness emerges from a nest of foliage to be silhouetted against our country’s sky.”14 The architect who had designed it was just one of the thousands of people in a state of transport.

RONCHAMP ENABLED Le Corbusier to articulate the true merits of his own achievement with new authority and simplicity. While he was glib with the journalists, in his public address he had told his audience, “The premises begin to be radiant. Physically they are radiant.”15

The architect expressed his foremost goal: his burning wish to give all people—every stranger who might enter one of his buildings at any moment—uplifting and salubrious experiences. There were “things no one may violate: the secret in each individual, a great limitless void where one may lodge one’s own notion of the sacred—an individual, totally individual notion. This is also called conscience, and it is an instrument for measuring responsibilities or outpourings ranging from the tangible to the ineffable.”16

“Ineffable” was one of the words he used time and again, because the concept of what was too great to be expressed in words, and too sacred to be uttered, was of such vital importance to him. For all of his cynicism about human greed and intransigence, Le Corbusier believed that everyone responded to visual wonder, that it opened up the heart.

The inauguration ceremony at Ronchamp on June 26, 1955

However misguided some of Le Corbusier’s decisions—aspects of the Plan Voisin; the attempted collaboration with the authorities in Vichy—his instinct had always been the same: to provide each and every human being with the palpable pleasures of which architecture is capable. In Ronchamp, the devices, at least as he described them, were simple enough: “curved volumes generated and regulated by straight lines…a kind of acoustic sculpture of nature,” evidence that “architecture is forms, volumes, color, acoustics, music.” In summation, he declared, “Architecture is an act of love, not a stage set.”17

The impulse to tap into clandestine sources of spiritual feeling had inspired the shelves with which Le Corbusier had fit his brother’s room in the house that had wrecked the family’s finances; the ramps of the Villa La Roche; the soaring entrance at the Cité de Refuge; the colorful facade of l’Unité d’Habitation; and the amusement park of vision offered by the great public buildings of Chandigarh. At Ronchamp, the “act of love” was the most rapturous yet.

THE EVENING AFTER the inauguration, some journalists asked Le Corbusier if he was happy with the way the day had gone. Repeating one of his lines from the early afternoon, he replied, “Why happy? I have performed my little task. Today that has provoked speeches that give pleasure to those who uttered them. Probably less to those who heard them. In any case, I hope to deliver a great blow to both the detractors of my architecture and to my imitators, those who imagine that architecture can be reduced to formulas. This possession of Ronchamp by the Catholic cult was extremely beautiful, very precise. It was the most precise moment of the whole day.”18

3

Normally, Le Corbusier wrote his mother and Albert together. On June 27, he wrote to her alone from Ronchamp. However assiduously he had encouraged her absence, he was desperate to share the thrill of his acclaim and his achievement with her. At the same time, he reiterated his warnings about the risks of anyone knowing the family’s background.

The letter was both a boast and a supplication. At the ceremonies on Saturday, Le Corbusier told “ma chère Petite Maman,” “Everything was cheer, beauty, spiritual splendor. Your Le Corbusier was honored to the highest degree. Considered. Loved. Respected.”19

Then he explained how delicate the situation was. For Ronchamp was a revolutionary work of architecture—radical in its approach to the Catholic rites and ritual: “By my architecture, worship is raised to the highest degree, purified, restored to the Gospels.”20 The best of the priests acknowledged this cheerfully. The opposition did not.

The architect’s attitude was grounded in reality but had a paranoiac tinge. He drove home the main points to his mother as if he were depicting a Last Judgment to an illiterate child. Repeating almost verbatim his dread of the response from the Vatican, he wrote, “Everything was joy and enthusiasm. BUT, the devil must be sneering in a corner, and it is his custom not to remain idle. Rome is keeping an eye on Ronchamp. I am expecting storms. And even vile and contemptible actions. That is why I myself have been, by necessity, vile and contemptible in making my recommendations to you on these three points. But I have no right to cease being vigilant.”21

He instructed his mother to go to Ronchamp, to open all the doors he had made there, not merely to see the interior but to enjoy her right to go behind the altar and climb the sacristy staircase. He sketched a bird’s-eye view of the church plan for her, drawing arrows to indicate the path she would take.

Then, in his endless attempt to please and humor her, he reported that at the inaugural banquet he had been seated to the right of the archbishop (a title he underlined to emphasize its importance) and across from the minister when the archbishop spoke about “L-C’s mother (because of the dedication to When the Cathedrals Were White).”22 He was determined that this dedication—“TO MY MOTHER, a woman of courage and faith”—reside at the forefront of her thoughts.

Le Corbusier had asked the archbishop to write her a postcard, which he enclosed. On its face, it showed a detail of the dramatically sculpted rough concrete of the church exterior. A massive, eyebrowlike corner of the roof, as well as the outdoor pulpit, are in view. On the other side, in neat script, is written, “For Monsieur Le Corbusier’s venerable mother, ‘a woman of courage and faith’ whom I had the joy to invoke this morning in the cool, bright chapel created by the heartfelt intelligence of her son”—signed by Marcel-Marie Dubois, the archbishop of Besançon.23

To a stalwart Calvinist, the praises from within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church may have meant little. But her son continued to try to make her proud.

4

The moment you glimpse Ronchamp from the valley below, you are drawn to it as to a powerful magnet. As you approach, the experiences multiply, with a lot happening all at once. The giant ram’s horn of a roof seems audible; concrete has been given the lightness of sound. It is a holy, resonant tone. Then there are the unusual forms of the towers, like giant periscopes, and the apparent faces on the many walls. Some of the masses are anchored; others soar.

Once you have taken in the forms, you notice the shadows—as important to the appearance of the building as what is solid. The roofline imprints itself on the surrounding grass and then moves. Other shadows resemble eyes and mouths and noses, so that Ronchamp sees and breathes, and gives out energy.

The chapel has a circulatory system that connects it to the natural climate. The flow of water off the roof, down the drainpipes, and out the spouts is emphasized by the overstated nostril-like gargoyles and the catch basins that receive the melted snow and summer rain.

At age twenty-one, when Charles-Edouard Jeanneret looked out of his window on the quai Saint-Michel and gazed at flying buttresses atop Notre-Dame, those fantastic jutting protuberances represented a language of hope and possibility after the clay-footed blocks of La Chaux-de-Fonds. Now he used architecture to express faith and optimism.

Inside the chapel, the tiny cracks of light between the immense sagging roof and the tops of the looming white walls resemble the slim lines of daylight seeping through the logs of those granges on the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds. He built Ronchamp out of concrete, but he also constructed it out of daylight (see color plates 18 and 19). And then he augmented the composition with color; the deep red of the walls of one of the side chapels evokes the blood of Christ, making that particular space feel like the chamber of a beating heart.

When you walk toward the altar, every step yields a change. Colors beckon you; their aftereffects come and go. Turn from one of the intense painted glass windows and then look at a massive white wall; you will see, briefly, that same red or yellow. That brief encounter with an illusory hue is the sort of psychic event Le Corbusier loved to orchestrate.

The tilt of the floor, the irregular and shifting depths of the windows, the helter-skelter pattern of some of the openings, and the roof that for all of its weight floats ethereally give a sense of sheer liberty. At the same time, there are traditional religious motifs. An arrangement of seven panes of glass refers to the seven sacraments; three windows evoke the Trinity; cruciform shapes are everywhere.

On the outside, nature changes the building perpetually. For Ronchamp is a transmitter for the cosmos, wearing a different covering with every movement of the clouds. Inside, the light shifts constantly, causing an ongoing performance. Le Corbusier has given his real gods—the universal forces worshipped in India as by the ancient Greeks—a modern temple.

LE CORBUSIER’S great admirer, Father Alain Couturier, an expert on modern ecclesiastical architecture, had understood why this was, indeed, a sacred space. Two years prior to Ronchamp’s opening, Couturier had written:

At first the extreme novelty of these forms will be surprising, but in short order…the sacred character is affirmed everywhere, and first of all by that very novelty, that unexpected aspect….

We may assert that it is in such edifices that we accede to that higher type of architecture which transcends pure functionalism and in which the dignity of functions is directly manifest (and already operative) in the beauty of the forms. In religious structures, these things assume their entire meaning: for a truly sacred edifice is not a profane edifice rendered sacred by a consecrating rite for its eventual use (as was recently written in an extremely ill-considered article); a sacred edifice is already sacred and substantially so by the very quality of its forms.24

Le Corbusier himself said of Ronchamp, “All I know is that every man has the religious sentiment of being part of the human capital…. I bring so much effusion and intense interior life to my work that it has this quasi-religious aspect, by which I mean to say that it is not an emotion of pounding drums.”25

It is as if what Bach discovered about the direct effects of certain musical cadences on the humor of the brain—and what experts in brain chemistry have found in the realm of psychopharmaceutical medicines—Le Corbusier had instinctively recognized about the effects of movement through architectural space and the sight of certain visual leaps and turns. Color, too, had those magical abilities that he cultivated; in combination with ever-moving form, it can impart well-being.

This amalgam of Stonehenge, Noah’s ark, and a spaceship, as infused by faith as the soaring Gothic cathedrals and as radical as Picasso’s boldest canvases, as true to the immediate necessities of construction and shelter as a cormorants’ nest on a remote island, and as sophisticated as the music of Stravinsky, evokes so many comparisons because, while being unprecedented in its architectural vocabulary, it joins them in its authenticity and force and as an embodiment of human courage.

5

Ronchamp is also a private homage made public. Inscribed into the chapel windows in large, bold script, at a low level, are the words “la mer,” the sea. We can also hear it as “la mère,” the mother.

The name “Marie” and the words “full of grace” loom largest of all. To the world at large, that name and description refer to the Holy Virgin, the mother of Jesus. But they are, equally, a reference to Le Corbusier’s private Marie, his own mother, who had also borne a “Le C” who would change the world and sacrifice himself in glorious excruciating martyrdom for his cause.

6

When asked about his intentions for Ronchamp, Le Corbusier had a stock answer: “I am asked what are my secrets for Ronchamp. There are none save a harmonious research among the problems raised. The Gospel: an ethic. The site: the four horizons. The means: a crab shell. Open your eyes and perhaps you will understand. Can the writer assist a man who does not find the meaning of the sentence in the words? One must seek out finesse while preserving force. Not for a moment have I had any notion of creating an object of astonishment. My preparation? A sympathy for others. For the unknown.”26

THE ARCHITECT WORSHIPPED the power of the sun, the wonder of conception and birth, the stupendous construction of all living beings. Ronchamp is their vessel.

He elucidated the visual miracles that many people considered holy. The most salient of these was light, the symbol of the immaculate conception with its ability to pass through glass without breaking it, the incorporeal equivalent of the Holy Ghost: “The key is light, and light illuminates forms. And these forms have an emotive power by the interplay of proportions, the interplay of unexpected stupefying relations. But also by the intellectual interplay of their raison d’être: their authentic birth, their capacity to endure, their structure, their boldness, the interplay of beings which are essential beings, the constituted beings of architecture…. I compose with light.”27

He was also attentive to the traditional religious elements required by his client’s goals. Le Corbusier gave close attention to the holy crosses within the chapel. He made them out of metal and concrete as well as the traditional wood. The symbols of Jesus’s death and martyrdom have physical and psychological weight; just looking at them, you imagine how heavy they are to bear on the shoulders.

When the human-scaled wooden cross made for the altar arrived at the building five days before the inauguration ceremony, Le Corbusier believed that that was the moment when the building ceased being a construction site. He saw it as a silent evocation of the great tragedy that had occurred on the hill of Golgotha and was now being represented on the hill at Ronchamp. Martyrdom was what affected him most of all.

7

The day before the inauguration of Ronchamp, Le Corbusier had begun a letter to Marguerite Tjader Harris that he completed shortly after the chapel opened. At one of the proudest moments of his life, the architect could not get over his regret at abandoning her idea of a colony of small houses where they could have been close to each other: “I am leaving to inaugurate the Chapel of Ronchamp. It will not perhaps be as beautiful as your nunnery at Vikingsborg, which was materially and spiritually inspired by you. I had written you the day after the tidal wave at Cap-Martin. You did not reply. I think you were navigating at the time between heaven and earth. Preferably heaven! As for me I’ve had the most intense regret for having to take the decision I was obliged to make. But the gods wanted me to be present at the tidal wave. I lost several years of work on a theme particularly dear to me. I should consider myself a dishonest or criminal person not to have warned you and to have begun work on the site that was ready for such activity. Hence I had the comfort of your friendship and your kindness in this matter. You have a vision, and that is rare! I was sure of creating something very fine for you. But you know very well that here on earth men do not do all that they desire (nor do women); later we shall speak of this again when we meet in the Upper Regions. But meanwhile I hope to see you again on this earth!”28

In the part he wrote after the opening, Le Corbusier complained about the coverage of the event in The New Yorker for being “without proportion and without much tact.” For all the praise, there were always thorns in his side: “We shall see what we shall see! The architecture of reinforced concrete has entered into the history of pure architecture, and moreover—what is even more amusing—the priests have said that this church inaugurates a new era. I am afraid that the pope is not very happy! He had sent a bishop to supervise the inauguration.”29 He hoped that, while a devout Catholic, Marguerite Tjader Harris would be more lenient.

8

A week after the opening of Ronchamp, Le Corbusier’s second great Unité d’Habitation opened in Rezé, near Nantes. At that ceremony on July 2, the architect publicly addressed himself to the representative of Minister of Reconstruction Duchet: “I am 68 years old. I have achieved a position throughout the world thanks to my researches concerning the structures of a machine civilization. I have created a hearth around the mother of the family, under new conditions of child-raising; I have re-established the ‘conditions of nature.’”30

He had not just made architecture; he had made a pact between humanity and nature. A contemporaneous newspaper pointed out that success: “These tenants, as in Marseilles, have formed an association. Their opinions? Out of 120 families questioned, only two are satisfied, 118 are enthusiastic. And these enthusiasts declare: ‘we prefer to live in the year 2000 rather than vegetating in 1830.’ Certainly this must be said: that everything has been admirably thought out and anticipated. Grouping 294 habitations without achieving a monstrous construction, but on the contrary a haven of peace, that is Le Corbusier’s merit. The labor of the mother of the family has been simplified. A true family hearth has been recreated in each habitation. Le Corbusier distributes freedom, silence, independence, verdure and nature.”31

This bold structure on the outskirts of the commercial capital of Brittany has a force and energy and a use of color all its own. Looming over the landscape, it is rough and impressive, an energizing amalgam of coarse stone and primary colors.

The other buildings of distinction in greater Nantes are charming factories—structures used for the making of biscuits and other butter-based confections indigenous to the region. Their architecture has the pleasurable quality of what they produce. Le Corbusier’s building, with its Modulor carved into the facade and its gigantic pilotis next to which we walk on a floor of flagstones, has gargantuan strength, a crazy vitality. Looming over the flat Loire landscape, its bright panels glistening in the sunlight, its rhythmic facade in nonstop motion, it is another bold declaration of human existence. As at l’Unité at Marseille, Le Corbusier gave people a new way to live.