LVI

1

Yvonne seemed somewhat better that summer. She and Le Corbusier were eager for their annual holiday—she because she had done so little, he because he had done so much. When they arrived in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin at the end of the third week of July, the architect was very pleased because “Vonvon” was able to walk from the train station to the cabanon.

Three weeks into the holiday, he wrote his mother that Yvonne “has the gift of catalyzing the right values. Instinctively she avoids bores and draws good people to her.” One of them, named Vincento, was another of her visitors who came to play the accordion. To his mother, Le Corbusier described his wife’s companion as looking like a little monkey and having some of the same attributes as peasant architecture: “He plays like a pair of thumbs, but sensitive thumbs. How far we are from the conservatories! Pieces from the Italian hills, from the mountains, enlivened by answering voices from the audience.”1

With all the acclaim Le Corbusier was enjoying, the rustic getaway at the edge of the Mediterranean was remarkable for its “utter purity…. Not one false note. Everything is natural, healthy, honest, and extraordinarily intelligent. I can’t stand bourgeois performances any more, with their commentaries.” In his high spirits, he read authors who shared that disdain of the bourgeoisie—Rabelais, Villon, Baudelaire, and above all Cervantes. He considered Don Quixote “an inexhaustible book…the finest of all, read and reread these last five years.”2

What an exceptional couple they were in their one-room cabanon (see color plate 16). While Yvonne, in the few hours of the day when she was sober, read, at most, fashion magazines and detective fiction, Le Corbusier, in the respite from his hectic professional life, not only read those masters but also plunged into Homer’s Odyssey.

His mother was mellowing. Marie Jeanneret sent a postcard to him at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin: “My dear boy! There you are, living in the laughing land of the sun, in peace and the joy of life, far from tumultuous Paris…. Repose, yes, you’ve needed that for a long time.” She now called Edouard a “good son and brother.”3

Le Corbusier’s spirits were dampened when Fernand Léger died that summer, but the architect accepted the loss of one of his few longtime friends with resignation. His fellow Chaux-de-Fondian Blaise Cendrars wrote him on the subject: “My dear Le Corbusier,…but fuck the devil! Léger just died, beautifully. He had a seizure, right there where he was standing. I embrace you, Blaise Cendrars.”4 Like Cendrars, Le Corbusier thought it was the right way to go.

WHEN HE RETURNED to Paris at the end of August, the architect put down the cornerstone of another project, the Pavilion du Brésil, and hastened to finish some large paintings. At the end of September, he believed he was about to start a big urban scheme for Berlin, putting him in such high spirits that he wrote his mother and brother, “I remain your humble and devoted Knight Errant, Quixotte [sic] by name.”5

When Le Corbusier’s plane landed at Berlin’s Tempelhof airport, he was greeted by more than two hundred journalists and the flashing of cameras from twenty photographers. He appeared on American and German radio and was very proud of his German, since he had not spoken it for forty years.

At an event attended by Gropius, Mies, Niemeyer, and Aalto, the speaker declared Le Corbusier “the world’s leading architect.” As always, he reported all his achievements to his mother, adding, “Berliners have no modesty, and therefore they want me to help them realize their dream of being the most beautiful city in Europe.”6

When he turned sixty-eight at the start of October, Le Corbusier, while pleased that his mother remembered his birthday, was worried about the handwriting in her letter. Fearful that Marie Jeanneret’s eyesight was failing, he counseled her to heat the house well and not to engage in false economies. Money was not a problem; he had sold a Braque that belonged to Albert for three hundred and fifty thousand francs.

His mother had to take care of herself because Yvonne would not. His wife, he complained, refused to accept the advice of doctors. Le Corbusier himself was in much better shape for having a shot of cortisone in the knee that had bothered him for four months, but when he told his wife he had gotten better because he had listened to the doctor, she remained intractable.

IN NOVEMBER, Le Corbusier flew to Japan. There was a big exhibition of his painting and tapestries in Tokyo and the chance he would design a museum. He thought the Japanese people were extraordinary and admired, the high level of aesthetic judgment in every aspect of their existence. Yet the perfection made him feel like an outsider: “Everything was plush and consideration, so much so that I finally refused to bite, for I’ll never be anything but a man waking each morning the same gullible idiot as the day before.”7

Violating his usual practice of returning to Paris between clients when he flew east, he then went on to Saigon, Karachi, and Bangkok, before ending up in Ahmedabad. On the plane from Bangkok to Ahmedabad, he began to anticipate his upcoming meeting with the Sarabhais and Shodans, writing his mother, “Tomorrow I’m stuck for two days with my Ahmedabad millionaires who, like the rich in general, are heartless and unscrupulous, quite incapable of appreciating anything.”8 He disparaged the way these clients felt themselves superior in the world because they had houses by Le Corbusier.

Then he was to spend a month in Chandigarh: “All of which is well and good, but Le Corbusier, that withered old pickle, is the odd type who’ll drop dead one of these days on the line of fire.” It was a strange sentiment to admit to his aged mother, but he needed her to know his fears and peeves as much as his triumphs. He was out of sorts: “The journalists, the radio, and the devil and his crew (the photographers among others) create that crazy, idiotic, disjointed atmosphere of modern times.” He expected his mother to understand his need for tranquility and recognize the shallowness of others, in contrast to his own purer values: “A little while ago I saw at an elevation of 6000 meters an absolutely fantastic cloud mass. Leonardo divined such things, and maybe [ Joachim de] Patinnier and Turner. Above the clouds, there is a conquest of weather meant for seasoned and sensitive souls. The rest, of course, are reading their newspapers, their magazines, their novels.”9

2

Work is not punishment, work is breathing.

—LE CORBUSIER

The buildings in a remote part of India quickly became known worldwide through publication. Along with the projects recently completed in Marseille, Ronchamp, and Nantes and the one under way at La Tourette, they established Le Corbusier as one of the most discussed architects on earth. His furniture designs were increasingly in demand, and his books and theories on urbanism were affecting architecture and planning everywhere. Regardless, he was not making a lot of money. He could afford his way of life in Paris and Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, pay for his mother’s chickens—not just on Christmas but on every Sunday—and allow himself the finest clothes, but he was not affluent. The architect had been driving the same modest car, a six-horsepower Fiat, for eighteen years and felt he could not afford a newer model.

“People say I am rich,” he wrote. “I don’t have a penny, I have never had money.” His lot had improved since the total penury of his first years in Paris, but he was far from enjoying the wealth of today’s celebrity architects. While, he declared, “the whole world builds according to my doctrine,” the remuneration was modest at best. “I am 68 years old. Architecture has left me nothing and brought me nothing.”10

The meagerness of his income was especially noticeable because of his latest client’s wealth. He was now building two houses in the Paris suburb of Neuilly for André Jaoul and his family. The Jaoul houses were large and luxurious, however meager their architect’s fees.

André Jaoul was an engineer whom Le Corbusier had first met on a boat to New York. After buying property in Neuilly, he and his wife had decided to ask Wogenscky to be their architect because they believed Le Corbusier himself was too busy. The architect who so often declined commissions flew into a rage—and got the job. He took the occasion to go in yet another direction. With their rough surfaces and primitive, grottolike forms, the paired structures represented an unprecedented approach to how the rich might live.

3

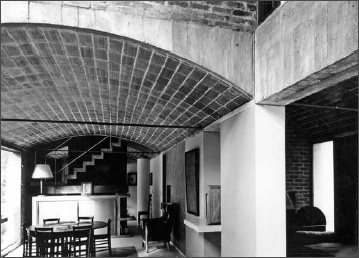

The two rectangular dwellings in Neuilly are set at right angles to each other, with the main entrances on the mutual courtyard in between. Both structures are defined in large part by their gently curved roofs, which, like the cylindrical forms of the Villa Sarabhai, derive from Catalonian vaults. Unlike the Villa Sarabhai, however, they were built in a climate that required that they be completely closed off from the elements. So the vaults rest on heavy walls that suggest a small turbine factory (see color plate 12).

The architect has encircled both structures with massive bands that cap the ground and first floors. The exterior surfaces are amalgams of squares, vertical and horizontal rectangles of varying proportions, and heavy cylinders. They are frenetically energetic relief sculptures that function as walls of marked resolution and stability.

In tandem, the Maisons Jaoul constitute a haven. They accommodate a privileged life with a place for cars, a lush garden, a large kitchen, guest rooms, and ample closet space; their enveloping forms also stimulate your mind and increase your alertness. While rather unappealing in photographs, in reality these structures soothe and invigorate you.

The moment you walk into House A—the first of them as you approach from the street—you feel a marvelous enclosure and warmth. Low ceilings are juxtaposed with tall chapel-like shafts of light. Shelves float musically from the living-and dining-room walls. Corridors beckon, inviting further exploration.

Thanks to the governance of the Modulor, a person of average height can reach up and touch, with the tips of his or her fingers, the base of the dining-room ceiling vault. A person of equal height standing on that person’s head could touch its summit; while no one was likely to attempt the acrobatics to put those measurements to the test, their logic and balance pervade the atmosphere.

An abundance of nature permeates the interior. Foliage high above virtually presses against the windows, while the tree trunks and lawn appear to enter the living room through the glass below; you feel as if you are simultaneously inside and outside.

In these two houses, you feel secure and happy as in a boat, filled with a sense of well-being and peace. You are coddled. But rather than feel bound or cramped, you feel emotionally elevated and viscerally released. There is both perpetual diversion and abiding harmony. Curves of plaster induce coziness. The other elements—wood, tiles, and concrete—invoke energy. And then there are the colors: concrete walls painted aqua, and other such transformations that enable what is heavy to become light.

The rhythmic spatial play is accentuated by marvelous textural events. Vertical wooden beams work against flat plaster planes and large, pure expanses of window glass. The red bricks of some walls and pebbly concrete blocks of others play off one another like instruments in a woodwind quartet. The concrete assumes the rich resonance of a bassoon; the glass floats in its tensile way like the music of a flute; the brick and the wood could be the voices of clarinet and saxophone. Each material sounds its own notes, but they also all work in unison.

HOUSE A has a little chapel in it—intended for private worship. The effect of its painted-glass windows and of a wall broken by shelves and altars is hypnotic. Elsewhere in the house, the ordinary substances of life are rendered equally religious. Because radiator pipes have been painted in bright colors, the passage of water, with its ability to heat as well as its plumbing function, is given the miraculous spirit it warrants.

On the second floor, a bright yellow slab of concrete is perched on top of a wooden cupboard under a white plaster vault. We are in a Romanesque crypt; we are also inside a late Mondrian! The concrete appears to float in the air; we are in something that no one else on earth had ever created before.

The fireplace is pure sculpture. Its recessed storage cube for wood is all red inside, with a green floor. The man who used these bold and cheerful colors was following the advice he perpetually gave his mother: enjoy and relish life. These vibrant hues are fabulously unnecessary; inside a practical storage unit, they are there only to enhance daily experience. The stepped chimney above the fireplace, with its little recesses, is equally generous—a puritan’s hedonism.

MADAME JAOUL, who was in her fifties at the time her house was under construction, asked Le Corbusier what she should do with her old family furniture once she moved into her new home. The architect told her to keep it and use it. But on another occasion he balked, “It’s me who decides. Merde! Merde! Merde!”11

The mother was compensated by the wonderful design details; her daughter was less happy. As a client, she felt intimidated by Le Corbusier: “On this site we always heard his raucous trumpeting voice giving orders. It was impossible to make him do anything, although he used to say, ‘We’ll make this house together.’ To most proposals he answered, ‘Shut up, little fool, I know what you need.’ And yet they did really make the house together as he said. One day Le Corbusier asked me: ‘What kind of a bedroom do you want, do you want to be all by yourself, don’t you want to be with your brothers?’ That’s the only thing he ever asked me. I said, ‘I want to be by myself.’ And he said to me, ‘All right, you’ll have your bedroom, I’ll show you.’”12 He kept his word, although she was disappointed that it was shaped like a corridor and separated from her parents’ room by nothing more than plasterboard, so that she could hear their toilets flush.

The kitchen of the Villa Jaoul, Neuilly, France, ca. 1955

From a child’s point of view, the impeccable aesthetics had too hefty a price. “We weren’t allowed to dirty our walls. Opposite my bed was a blue wall, and I was constantly told, ‘You can’t scribble your drawings on the wall. Look at that blue panel, it’s so beautiful the way it is!’ All right, the blue was fine but…this house always seemed so sad to me. Very beautiful, beautiful and sad, like a museum. It’s a house that lays down the law…. Le Corbusier was a God for everyone. Except for the children.”13

4

At the start of 1956, Le Corbusier was invited to join the esteemed Institute of Architecture. He proudly described his response:

Yesterday, January 3, 1956, M. X, a member of the Institute, asked me to meet him about an important matter. Fifteen minutes later he put this question to me: “Are you willing to join the Institute?” Answer: “No thanks, never.”…The Academy is sick, it has a French disease. France has lost the line of architecture which for so long was one of its chief glories.

A diploma of mediocrity is awarded to a couple of hundred fellows each year, entitling them to practice architecture. They are given examples such as the Paris Opera + the Grand Palais + the Gare d’Orsay in Paris…. At best a few real minds might be able to manage the history of Architecture. But not the rest!…Becoming a member of the Institute is not only a consecration, it’s an adhesion…. Alas, dear Monsieur X, you must not stay on the line of fire, where real bullets are aimed at you and where life is hard!14

He preferred to venture into new territory rather than to align himself with the architectural establishment. Junzo Sakakura, an architect who had worked at 35 rue de Sèvres in the early 1930s, asked him to design a 230-square-meter curtain in 1956 for a theatre in Tokyo; Le Corbusier worked on it in the nude at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. “I had sought and found, but I was still quite uncertain, dubious, dubious!…Suddenly (like a whiplash!) I catalyzed: a new project leaped into my understanding. On August 18, I was drawing it stark naked. The Modulor afforded me splendors of organization and indisputable harmony.”15

Following Matisse’s example, Le Corbusier made a maquette of cut paper pasted in position. After sending it to Tokyo, he declared, “What delights me is that I have the feeling (modesty!) of having made a mural masterpiece, something never achieved before: a wall of 230 sq. meters in woven wool. It will spit fire and it’s wildly new and grand, and entirely of today.”16 The son of the man who had only done miniatures was working on his preferred scale.

5

On February 7, 1956, Le Corbusier wrote “an open letter” to the prefect of the police of Paris to put forward his ideas on urban living. In it he lamented the fate of a city strangled by automobile traffic, the lack of available housing for young couples as well as old, and the increased number of slums. He then described a number of the solutions he had proposed over the years—among them the democratic concept of four airports, one east, one south, one west, and one north of the city, linked to the center of town by special motorways: “I happen to belong to the category of beings who concern themselves with what’s none of their business: they aren’t qualified by a diploma nor by any official function. In this whole business I was preoccupied. Incorrigibly curious about the human problem, the key to the problem. The human factor! I’ve always been concerned with the human person, whose heart is moved and curiosity awakened and mind always inclined to invent solutions by a fundamental ingenuity—that optimistic, joyous, and investigative force which leads me to building.”17

Those of us who lament the lack of affordable housing, who have experienced the pollution, and who have sat in interminable traffic jams between Charles de Gaulle Airport and the center of Paris might well feel that we would all be better off if Le Corbusier’s voice had been heard on these subjects. One of the main reasons his advice was not heeded was that what he attributed to the blindness of his listeners was often the result of his own blindness in failing to recognize how he antagonized people who might have supported his theories.

With his passion for recounting the slights against him, Le Corbusier reported on the laceration he had received from Dr. Alexis Carrel. Carrel disapproved of his urban schemes for Bogotá and Chandigarh. He quoted Carrel saying to him, “‘All in all, you build vertically like the Americans, and I’ve demonstrated in Man, the Unknown how the Americans have stuck us with a dangerous and threatening civilization.’”18 The ever-defiant Le Corbusier had given Carrel a copy of La Ville Radieuse, but the doctor had completely rejected its ideas out of preference for the style of bungalow he had seen in California.

Recounting this to the prefect of police, Le Corbusier made no mention that he and Carrel had worked as the closest of allies under the regime of Maréchal Pétain, nor that the terrifying Carrel was someone Le Corbusier had cited to his mother as a source of ineffable wisdom.

The combustive quality of Le Corbusier’s fury now brought out a new extreme of confused and paranoic megalomania. “I was (crudely) cheated out of my plans for the Palace of the United Nations. Sulking in my tent, I smile with a malice mitigated by altruism and playfulness, knowing that along with this Palace is incised, in the hide of a baffled New York, a juvenile graft of the ‘Radiant City,’ in other words the fruit of forty years of meditation and research on the way in which man himself, henceforth projected into a machine civilization, could survive in this Homeric adventure, having looked, seen, read, retained, sought, found, decided and acted, having surmounted this phenomenal adventure of machine life which Louis Vauxcelles, around 1921, in the early days of ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’ (our review which concerned itself with precisely this matter) declared to be a good old refrain of the pure French tradition: and he called to witness the chariot of the Merovingians, and with the strength of that insight he concluded that nothing new had appeared on the horizon ever since!”

The prefect of police may never even have read this letter, but if he reached the final paragraph, he learned that Le Corbusier divided humanity into two categories—egocentric liars and brave revolutionaries. “With this classification, and with modern means, the present problems are solved—especially with regard to authority. The impasse is surmounted. The sap flows again—it is springtime—and circulates anew. It nourishes all things. It gathers strength from its roots which are eternal and natural. The roots are not up in the air, nor the treetops underground. No! And this ‘new’ occupation of the territory recovers the most permanent places and paths, going all the way back to prehistoric times. These are the constants of our sojourn on this wrinkled sphere, where nothing is extravagant but the reign of lies, whose true countenance = selfish interests, fear, ignorance, petrification. Nothing is revolutionary but the act of putting the car back on the train or on the road or on the tracks, if derailed or smashed. It is a powerful gesture. And it disturbs…by restoring. I offer you, Monsieur Commissioner, my respectfully devoted sentiments.”19

Convinced more than ever that the drive for personal advancement and the hunger for money were destroying the world, Le Corbusier, at such moments, was not in his right mind.

6

When Le Corbusier witnessed humanity and generosity, however, he heaped praise in the same extreme manner that he unleashed rage. In 1956, Jean Prouvé, with whom Le Corbusier had periodically collaborated on housing ideas, made a small, simple prefabricated house on the banks of the Seine. Its concrete base sat on a bed of stones. The main materials were aluminum and Bakelite; its “bloc sanitaire,” which contained the heating, toilets, bathroom, and kitchen, was manufactured elsewhere and lowered in place by a crane. Le Corbusier was unstinting in his admiration for the intelligence and modesty of this low-cost dwelling, calling it “the most beautiful house I’ve ever seen: the most perfect way to live, the most thrilling thing ever constructed.”20

Le Corbusier still had his own hopes of improving human existence. There were more than twenty new projects on the drafting tables at 35 rue de Sèvres that year, even more in 1957. They ranged from chapels in six different locations in France, Switzerland, Belgium, and Germany to a hospital in Flers in Normandy; a hotel in Berlin; an apartment building for UN employees in New York (remarkably enough); a congress hall in Thun, Switzerland; a new plan for Les Halles; an ashram in India; a psychiatric hospital in Amsterdam; an art center in Nice; an office building for Air France in Paris; Unités d’Habitation and apartment buildings at locations all over France; and private villas from Nice to Caracas. But not one of these was built.

He now weathered most of his defeats with grace, but what happened following another conference on urbanism in Berlin devastated him. Le Corbusier was one of 13 architects, out of 151, who had made the short list for developing a new urban scheme there. His plans were then rejected. Le Corbusier was convinced they would have won had not Walter Gropius, who was to be on the jury and would have supported him, become ill. Le Corbusier no longer expected every one of his ideas to succeed, but the hope of redesigning the metropolis where he had once slaved away for Peter Behrens had tantalized him.

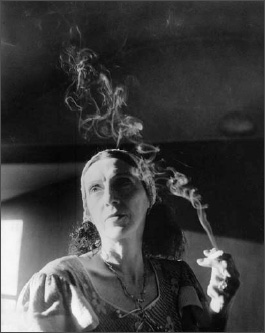

Yvonne in 1949

When he was in Paris, he painted or worked on sculpture or tapestries every single day. But Yvonne had become so difficult that the architect could never stay home for long. Then, once he was away, he became desperate. “Dearest Von, I love you more than ever…that’s how it is!” He sent her articles about the effects of smoking and lectured in letters that all the pastis was killing her appetite. Knowing she would explode at being given any advice face-to-face, he wrote,

Your health is in your hands. You are amazingly healthy—an iron constitution.

You’ve had one bad deal: your bones.

You don’t take care of them.

You’ve got prescriptions.

You don’t buy the medicines.

You have no notion of the life I lead. Anyone else would have croaked long since!

So help yourself, and heaven will help you…. And so will I, who have retained all my affection for you and also (yes!) my admiration. You can work miracles. Do it!21

In letter after letter as he traveled, Le Corbusier begged his wife to be kind, praised her, urged her to eat, and insisted she take better care of herself—starting with having X-rays. He referred, on April 4, 1957, to “36 [sic] years of perfectly happy life thanks to you.”22 Three weeks later, he wrote about “all that you’ve been for me: an empress’s daughter giving despotic commands and a childish waif so sweet, so pretty, so full of charm, so loving (behind her grumpy facade).”23

Le Corbusier was still obsessed.

7

In 1957, Le Corbusier and Yvonne spent their usual August holiday at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Jean Petit visited them that summer and was struck by the robustness of the septuagenarian Le Corbusier. On one occasion, however, Petit was alarmed by the sight of him struggling to climb back out of the sea: “Just as he grabbed the iron ladder to climb back up out of the water, a stronger wave prevented him. Then another. Each time, he was pushed back and violently crushed against the rocks. After several attempts which I watched helplessly, he managed to get up onto land, green rather than white. After having caught his breath, he told me: ‘You see, the Creator is always there to remind playboys like me that they’re not much, and that’s just when you have to react, when you have to fight back.’”24

AFTER “M. ET MME. LE CORBUSIER” returned to Paris that autumn, Yvonne began to fall even more frequently while still failing to recognize the pain of her own broken bones. At moments, however, she again started joking—overwhelming Le Corbusier with her good spirit and warm heart. When she died at four in the morning on October 5, 1957, the day before Le Corbusier’s seventieth birthday, her husband was holding her hand.

Le Corbusier wrote that his wife passed from life “in silence and utter serenity. I was with her at the clinic for eight hours, watching her—quite the opposite of a nursling—taking leave of life with the spasms and mumblings in a tête-à-tête that lasted the whole night. She departed before dawn.”25

Even if the very end was graceful after all those years of misery, Le Corbusier was devastated. To friends he sent out a reproduction of a drawing of his and her hands clasped together, but no form of memorial was sufficient to assuage his despair.

AS WITH HIS FATHER, following Yvonne’s death he voiced only unequivocal love and admiration for an individual he deemed totally selfless and kind and the soul of goodness: “A high-hearted, strong-willed woman, of great integrity and propriety. Guardian angel of the hearth, of my hearth, for 36 [sic] years. Beloved by everyone, adored by the simple and the rich alike for the pure riches of her heart. She measured people and things by that scale alone. Queen of a tiny fervent world. An example for many, and entirely without imitators. In my ‘poem of the right angle’ she occupies the central place: characters E3. She lies on her bed in the guest room, straight as a tomb figure, with her mask of magisterial country bones. On this day, feeling calm, I can believe death is not a horror.”26

The crusty and often outrageous Yvonne Gallis was, indeed, for people like the young Robert Rebutato and the fishermen at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, every bit as decent and amiable as her husband remembered. She was as addicted to acts of generosity as to alcohol. Even when the former beauty had completely disintegrated emotionally and physically, her deep-seated kindness, complete indifference to pretension, and Mediterranean earthiness had remained intact. Toward the end, Yvonne had developed the habit of giving cartons of Lucky Strike cigarettes—the amount had expanded from mere packages—even to strangers. It was an extraordinary gesture, especially for a frugal person. Many people who met Yvonne remembered that eccentricity above all else.

Though the creature Le Corbusier had saved in the Bois de Boulogne had flown to freedom, this wounded bird had stayed. She was always at home, and her need for him was a rare constant in his tumultuous life. He had no children, but she played, in many ways, the role of a needy child. She was the one person in the world who depended on Le Corbusier completely, and acknowledged it.

In his own way, Le Corbusier had adored his wife and never failed to provide for her. In return, this kindhearted, tough, temperamental woman was a source of stability that energized him. And even though she hurled verbal abuse at him, Yvonne, unlike his mother, revered Edouard—not as an architect, but as a man.

A WEEK AFTER Yvonne died, Le Corbusier responded to a condolence letter from Pierre Jeanneret, who was in India. Thanking his cousin for the, precious comfort his words had given, he wrote, “Her death revealed Yvonne in a luminous intensity transcending anything imaginable. She (Yvonne) is in the hearts of so many people. In addition to these words, I think I can report that there is no reason to be pessimistic about the concluding work on the Capitol. Someone high up is watching over the future. I have my contacts. Perseverance. It would take only a moment of inattention for a collapse into the kingdom of failure of an enterprise which, by the energy of 4 or 5 individuals, may just as well terminate with a magnificent burst of brilliance. Impossible to say just when I can get to Chandigarh. Wait for November.”27

Not everyone would have jumped so instinctively from the subject of his recently dead wife to the challenges of making architecture. But Le Corbusier was ready to get back to work.

The issue with which he was wrestling above all others was human goodness. There were people like Yvonne who were decent and emotionally honest, and then there were bureaucrats, academics, journalists, and authority figures who applied their power unworthily. The world of architecture was full of vipers; he had needed this rare woman with whom he had no doubt where he stood. Life was a battle in which one side acted out of kindness and good intentions, the other out of selfishness and cruelty. For all their intellectual differences, for all her eventual toughness and all his errant ways, Yvonne and Le Corbusier, two strangers in the world, had been good to each other.