LVIII

We have been the ones to receive kicks and blows on the nose, the back, the head, or wherever you like. Such things occur. Much work has been done, even so, and I am certain that the next two generations, in fifty years, will have achieved something remarkable. If poetry is not in the facts, it will be in the hearts of men, or in their desire. But they will always argue with one another. There are those who make money out of their ideas, and they will always make money. There are those who put vanity into their ideas, and they will always be vain, and those who have a certain social spirit and who will try to talk together. Which is difficult, for it takes time, and such problems require a long development; they cannot be flipped like a crêpe. This entire task facing modern society is addressed to those who have the desire to give to something and for something. They will be called “dupes” by some of their friends. And “the friends of society” by others. We do not work to be praised, we work out of a duty to our conscience, which is within every man and which is there to tell him whether he is behaving well or badly.

—LE CORBUSIER, ON THE LAST OCCASION OF HIS BEING RECORDED SPEAKING, TWO MONTHS BEFORE HIS DEATH

1

Le Corbusier had clandestinely involved Marguerite Tjader Harris in the development of La Tourette. In September 1956, when construction had just begun, Le Corbusier sent a Dominican father to Vikingsborg to meet her and discuss the convent. “Of course these Gentlemen are going to talk finance to you,” he wrote, “but I should like to say something so you will understand that they are doing so with complete disinterest, and I should also like you to know that the Dominicans of Lyon have shown themselves to be magnificently open to the most modern ideas (which moreover as they emerge from the Atelier Le Corbusier turn out to be ideas precisely congruent to the decisive periods of architecture’s birth in the west around 1000 or 1100, at the moment when, at the instigation of St. Bernard, certain monasteries of great architectural power were built, free of any superfluous decoration and representing pure architecture, i.e., architecture only). The Dominicans have had to insure, by a loan or by gifts, the conclusion of their undertaking, that is, the final millions, which extend beyond their budget but which we cannot do without if we want to remain loyal and honest architects.”1

Le Corbusier assured Tjader Harris that she could not possibly put her inheritance to better use. The undertaking was to realize the best ideas of both Father Couturier and himself, an unbeatable combination.

He continued the entreaty with a second missive. Le Corbusier underlined the importance of the project and the courage of his Dominican clients. He had exceeded budget in spite of all of his efforts not to do so but was loath to compromise the integrity of the building. He had agreed to create La Tourette on a shoestring, and while he had complied, they still needed her help.

Le Corbusier made his request, and gave the history of the monastery, with characteristic candor: “God knows you have Ladies and Gentlemen who come fund-raising, since the day your Maman left you more than you need to pay for lunch and dinner every day! But our friend Father Couturier was a master; it was he who got the Monastery of La Tourette going. He died very suddenly in his hospital bed two days after having informed me that he was cured of his muscular asthenia [sic] following the violent shock he received when Rome took her dramatic decisions against the ‘worker priests,’ especially the Dominicans, who had employed nonacademic methods in the practice of their convictions. This monastery of La Tourette is therefore (forgive me) a very strong, valid work to which I have devoted all my talents. I’d be happy to think that when they put fifteen centimeters of soil in which grass will grow and perhaps some tulips and narcissus, ordered from Holland, on the church roof, it will be thanks to your dollars that this smile of the earth could be addressed to the heavens. You are a brave girl. I have nothing but the best memories of you. And you know perfectly well I’m no fund-raiser.”2

There was no chance of Tjader Harris providing financing, however. By now the heiress had paid for a chapel on her Connecticut property, which she had in turn given to a convent. The sisters were settling in, and she was moving into the garage apartment to function as their secretary. She was effusive and admiring to Le Corbusier in response, but her funds were depleted.

As always, she urged the architect to visit, but now with a new twist: “If ever you’d like to get some rest in a northern Convent, surrounded by gracious and silent sisters, come, come and find the Peace of a house of God beside the salt blue sea. (They accept pilgrims, men and young people.)”3

LE CORBUSIER WAITED nearly three years to answer. When he did, he acted as if Tjader Harris’s letter had arrived only the day before.

In 1956, the American divorcée had signed her refusal to fund La Tourette with “all my admiring and affectionate thoughts.” In July of 1959, Le Corbusier wrote her, “You kissed me off in your reply of October 9, surrounding your refusal with any number of kindnesses and favors and even inviting me to visit you as ‘pilgrims, men, or [sic] young people,’ as you put it.”4 Now he was back with a more modest and realistic financial proposition. He was attaching a document with the Dominicans’ needs marked in red. He pointed out that in the previous two years, Ronchamp, which had opened its fantastic door only four years prior to his writing, had seen its annual income from entrance fees rise from four million to thirty-three million francs. The builders of the church had been penniless at the start; now their courage was paying off. He expected similar success at La Tourette.

Le Corbusier made his entreaty: “Dear Friend, money has to be good for something. If you don’t want to give any, be good enough to contribute to the loan being proposed.” He attached photographs and stated his case: “It’s a crate of ‘divine’ proportions. The interior has a stunning kind of lighting. The walls are entirely raw concrete…. The hundred cells for meditation are oriented around a huge flat surface facing…the sky.” And he summarized his own attitude toward money: “An excess of money is pure sterility. It’s easy for me to say so, since I’ve never had any. And yet…at this very moment there is coming into being a movement for the purchase of painting by Le Corbusier all over Europe. Imagine, Le Corbusier honored everywhere after thirty years of silence! And perhaps I’ll have some change in my pocket. I can assure you quite simply that the vanity of money seems to be an obscenity at this particular moment. So long as people have to fight for life such combat is licit; once the proportions change, the very definition of money is in question once again!”5

Marguerite Tjader Harris, surely, was one person who would understand his personal plight, his frustrations as well as his dreams, and the paramount importance of his architectural goals. “Soon you’ll be taking me for a Preaching Friar; which is hardly the case,” he continued. “I’m leading a terrible life, my travels criss-crossing Europe. They’ll do me in, if it goes on much longer. On August 1, I’m going to see my mother who’ll be a hundred next year. P.S. Last year in Brussels I made a devilish thing: the ‘Electronic Poem’ in the Philips Pavilion. I can promise you it shook out the fleas from those who saw and heard it. But it was a localized manifestation. Now I’m looking for the possibility, in my Monastery, of being able to extend certain sonorous experiments from the Philips Pavilion.”6

Again, Tjader Harris had to turn him down, though she profoundly admired La Tourette: “Everyone is delighted by it—including your humble friend in Darien.” But she was building onto the convent in Connecticut. She had a proposition, however. Le Corbusier could raise funds if he would grant her an interview for the American publication Liturgical Arts. Convinced that such an interview would lead to contributions from readers, the following day she sent questions and ideas for the article in a letter which she signed, “Your secretary, servant, friend…Marguerite.”7

Tjader Harris offered to pick up Le Corbusier at Idlewild Airport, perhaps if he was on his way to Boston to work on the arts center he was undertaking for Harvard University. She amplified the offer with an enticing detail: “I have a shack here, quite nearby, at the sea’s edge, heated and full of tropical plants.”8

By the time Tjader Harris’s letter arrived at 35 rue de Sèvres—following the celebration of that hundredth birthday he had admitted to his lover would actually occur the “next year”—the architect was back in India. His secretary acknowledged its receipt and forwarded it to him. Le Corbusier answered four months later by having the secretary write on his behalf: “Madame, M. Le Corbusier will be in India until approximately May 15. He would have liked to write you personally, but he has requested me to inform you that since the New Year began he had been leading a very fatiguing life. Having been ill in January and February, his work has accumulated, and he was subsequently obliged to make four successive trips in less than a month.”9

Their relationship was not yet over, however. Le Corbusier and Marguerite Tjader Harris were to see each other one more time.

2

Six years after Marie-Alain Couturier died, Le Corbusier did justice to his patron’s vision and completed the monastery complex.

La Tourette looms large on the hillside. Like Iviron on Mount Athos, it initially appears top-heavy. The windows and pilotis of the bold convent give the illusion of hanging loosely from a roof that is mysteriously fixed in place, like a taut curtain rod without visible supports. While in truth the vertical structure within the walls holds up the top, it appears like a religious miracle—as if what is above is floating in space independently, with everything else suspended from it.

This unusual building is exciting but discomfiting. It does not soothe or welcome. Its surface of rough reinforced concrete is cold, and its complex fenestration is challenging, full of shadows and of suggestions of what is unknown and cannot be seen. The structure echoes the rugged and somewhat secretive lives of its inhabitants.

Once you are inside, La Tourette resembles a grim high school or administrative building, with dark corridors going in myriad directions. But then you reach the church. The experience is without precedent. Like Ronchamp and the interior of the auditorium of the General Assembly at Chandigarh, this place demonstrates Le Corbusier’s unequaled imagination. It reveals artistic bravery and gives courage.

The church offers the celebration born of tragedy. A tall, generous space, it feels like a small, heavenly city. Yet it is a cavern that conjures those underground refuges in which Charles-Edouard Jeanneret found safety during the bombings of 1917—deep, dark spaces with light seeping in from above. It also recalls the tall, unadorned barn at La Chaux-de-Fonds, similarly illuminated mostly from above. This stark interior like a gigantic cellar is hard to reckon with. It is unbelievable that the heavy blocks that make up the flat ceiling above don’t fall and crush us. Yet they float ethereally over the narrow clerestory windows.

To look up and around and walk through the space is to have one jolt after another. The colors beneath the bands of fenestration are bold and powerful. The pitch-blackness in front of the organ suggests the power of music that will emanate through the church. The altar, again with unexpected colors, is a surprise. Compared to the Baroque church within the monastery at Ema, this is blood and guts, a raw and tough encounter (see color plate 20).

The cinder blocks and concrete are painfully honest and devoid of covering. The radiator pipes are uncompromisingly factual. The cement floor—patterned according to the Modulor, which Le Corbusier renamed “Opus Optimum” for the occasion—and the rough slate of the altar do nothing to soften the impression. But for all its brutality, the church is majestic and simple. And it emanates truthfulness.

IN THIS harshly minimalist space, dramatic lighting ushers in intense delight. It comes both from a single square skylight punched into the flat ceiling and from that ever-so-narrow band of clerestory lighting—both at the altar end. Far below, to the left and right of the altar, there are more small windows, pristinely simple openings composed of right angles and straight lines.

Because the clerestory strip has been divided into three distinct units, the light recalls the Holy Trinity. But, equally, it could represent Le Corbusier’s personal holy trinity of sea, earth, and sky. The plain windows to the left of the altar, three on one side, four on the other, invoke the seven sacraments or the seven days of the week.

At the opposite end of the church, behind another altar, a vertical window is stretched to its ultimate height and narrowness. A sliver of light makes its way into the church. A more diffuse light arrives from the two chapels that jut off of each of the long sides. One of these chapels is in the courtyard of the monastery, the other on its exterior; they both are well lit from above, and their muted glow beckons you to come in from the darker sanctuary.

When we accept this summons to leave the larger sanctuary and go into the chapel growing out of the outer wall of the convent, we feel as if we are in a crypt. The crypt floor is a series of broad platforms that proceed down shallow steps, following the natural slope of the land. Each platform has its own altar, allowing for priests to celebrate individual masses. The concrete walls behind the altars are painted a striking orange-red and a celestial blue; that blue is also used for the ceiling.

Opposite those brilliantly colored walls behind the altars, a concrete wall undulates like ribbon. Convex at the top, it twists itself into concavity moving downward, while at the same time it leans in as if blown by a strong wind. Fantastically, daylight pours in from above through three circular wells—or cannons. Again, the number is holy. The inside of the first is painted white, the second red, the third blue. From the outside, where these wide cylinders emerge from the chapel roof, they look like periscopes or gigantic compressed Slinky toys. The shapes cause an ever-changing, unpredictable light and color to fall below, as if they come from a spiritual realm. The light coming in at these angles is unique in the history of building design. It has a stunning effect and gives the two candles and small crucifix on each of the altars below a crystalline majesty.

Iannis Xenakis deserves credit for these light cannons. Creating La Tourette, Le Corbusier had become increasingly dependent on others in his office. The work on the monastery began in 1953, in the heady days when the architect was also building in India and completing Ronchamp and other major projects. This was well before the difficulties over the Philips Pavilion, and Xenakis had been given the assignment of transforming Le Corbusier’s quick sketches into actual building plans. In the course of that work, Xenakis had invented these new forms to illuminate the monastery chapel.

Xenakis was equally responsible for the marvel we encounter if we yield to the temptation to go off from the main sanctuary in the opposite direction—to which we are beckoned by a small opening suggesting a chamber of mysteries beyond. Proceeding that way, we enter the sacristy. This chapel has seven angled cannons of light. But whereas the ones over the crypt are round and at differing angles, these unprecedented sources of illumination have flat sides and trapezoidal cross-sections (see color plate 21).

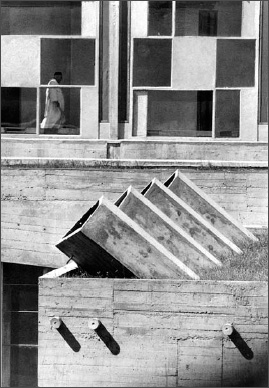

Light cannons at La Tourette, ca. 1957

The ceiling of the small chapel lit by these lopsided, energized forms is painted a bright yellow. Inside and out, this chapel is yet another occasion at La Tourette when celebration acquires raw force. This lurid space with its crazy septet of light sources is charged with the reality of death as much as the solace of religion. It exudes the power of our most primitive and authentic emotions.

3

Supreme achievement and outstanding capacity are only rendered possible by mental concentration, by a sublime monomania that verges on lunacy.

—STEFAN ZWEIG, “Buchmendel”

La Tourette has, in addition to its sanctuary, all the elements of a monastery of the type Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had initially studied at Ema and inhabited on Mount Athos. It’s hard to know what to attribute to Xenakis or others on the staff at 35 rue de Sèvres and what to credit to Le Corbusier’s own genius, but the complex in central France is endowed with details that cause everyday acts to waken the mind.

The corridor that provides access to the cells runs around a square interior courtyard, so that you take a quiet walk in fresh air before reaching your home base. You then enter the assigned residential unit on the side of the corridor opposite the courtyard—and proceed into a space that, at its far end, opens to a broad, seemingly infinite expanse of nature. The visual and tactile details of the cells have been carefully considered for the experience they provide. Most of the units are 5.92 meters long and 1.83 meters wide; their height is 2.26 meters. Unsurprisingly, these are all Modulor dimensions.

These rooms for solitude are welcoming and at the same time challenging. You feel that your needs are thoughtfully accommodated, and everything is clean, but the amenities are rudimentary. As you enter, a simple washbasin is on your left, backing up to a short entrance wall, alongside the door. Directly in front of you, a plain armoire forms a sort of partition, parallel to the entrance wall. On the other side of it, a narrow bed runs along the sidewall. A basic desk at the far end is placed perpendicular to the window wall and affords a sideways view outside. A modest desk lamp and straight-backed wooden chair, the remaining essentials, are in place.

The main activity in one of these rooms is lying, awake or asleep, on the cot, which is not much wider than a bench. You observe and reflect in conditions that echo those of a second-class train carriage. The rough and brutal is juxtaposed with the poetic.

Lying on the hard bed with scant adjacent space, you feel compressed, enclosed by coarse and pebbly plaster that is stark to look at and cold to touch. Its hard, deliberately ungracious surface is unadorned by pictures or decoration of any sort; it becomes a tabula rasa for contemplation or fantasy. The green linoleum floor, surprisingly cushioned and soft underfoot, is a practical solution at the same time that its color and synthetic quality are jarring. Inexpensive and washable, this could be a surface in a hospital corridor that has to stand up to traffic; the governing force was that it was easy to maintain.

A machinelike and spare dwelling space, the cell ensconces you in silence. Its austerity is initially unsettling; there isn’t a hint of luxury or embellishment, and the linoleum and rough plaster and coarse bed linens do nothing to comfort you. But then there is, as the conclusion of the space, facing the landscape, a composition made by a window, a narrow door (about eighteen inches wide) to the small loggia, shutters, and draperies. The window frames and the solid panel are yellow, the louvers orange, the other moving parts green. While the radiator pipes, underneath the window, are painted black, the wastewater pipes are cobalt blue. The colors lend charm to these assorted elements.

Moreover, lying on the bed or sitting at the narrow desk, you look beyond that composition at the offerings of the world outside. Be it night or day, fine weather or storms, you can proceed onto the loggia, which runs the width of the cell and is 1.47 meters deep. Some of the cells adjoin lush woodland foliage; others open to a mountain vista. Infinity is the reward for your modest accommodations.

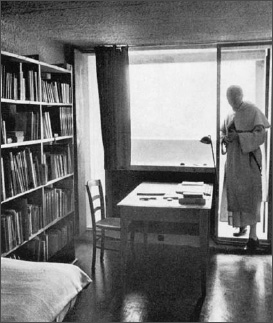

One of the residential cells at La Tourette, ca. 1957. The bookshelves were rare, a special feature for one of the permanent residents.

4

The bare lightbulbs, rough shelving, and simple sink in each room fulfill life’s requirements without pandering to vanity or wastefulness. They compose a modest, unassuming stage for the great richness of observation, thought, reading, and writing. The living space that is like a splash of cold water on the face serves as a platform for the salubrious experience of nature that had always been essential to Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. He lived in a mixture of necessity, pain, and poetic abundance. The devices of his architecture combined the same elements. He achieved for the residents and visitors to a monastery the same blend of rigor and beauty he had realized in his own retreat on the Côte d’Azur.

The auditory experience at La Tourette is comparable to the visual. The sounds throughout this carpetless building complex are as harsh as those on a clanking train. In your room, even with the door and windows shut, you hear other people using the plumbing or closing their doors. The mechanical crashing reverberates in your ears. Simultaneously, from outside, there is the symphony of the birds.

5

The stairs that link the floors of the monastery complex are steep and challenging. These long flights of steps are at an unusually sharp incline; the spacing of the treads and risers is uncomfortable and physically demanding. That design forces you to get from one level to the next with maximum efficiency. Le Corbusier publicly lamented that too few people in the world walk upstairs two steps at a time; at La Tourette, he forced the reach of the legs.

There is a deliberate discord; things are at odds with one another. You go from the calm of nature and flowers, the poppies in high grass on the roof, to rough masses of concrete. You jump from the brutal candor of a metal drainpipe to a lovely and poetic play of soft colors. The kitchen door handles inject unexpected pleasure. The tough and the gentle, the factual and the charming, are united.

IN THE LARGE central courtyard, a pointed pyramid form sits on top of the square oratory. Inside this simple space are modest benches. A rough stone slab forms the altar. Pencil-thin vertical windows that penetrate the pebbly, white plaster walls are the sole distraction as one looks upward to the high ceiling formed by the pyramid. The only traditional objects are a small crucifix on one of those walls and the Bible that lies open on the altar.

The stillness and quietude here are breathtaking. The effect of the void and the leanness are infinitely soothing. Adornment would be an offense.

From the outside, the pyramid creates a visual stop, a stasis in the midst of all the slopes and curves and light cannons. It resembles a metronome and functions as a similar means of balance. Is this yet another homage to his mother, to music, to the possibility of a dependable core to counter the whirlwind of life?

6

Brother Roland Ducret was on the scene when La Tourette was being built. Forty years after the monastery opened, his memories of Le Corbusier are still vivid. Brother Ducret recalled that many members of the order had been enthusiastic from the start, while others never wanted to set foot in it. The architecture was not the only issue. While Father Couturier had the idea that the monastic life was worthwhile and that the Dominicans should return to it, others objected to the idea of being at a remote location in the countryside. Their tradition was to work in cities—as opposed to the more reclusive life of the Cistercians.

For those who accepted the principle, Le Corbusier was an ideal collaborator. If to his wealthy clients like Manorama Sarabhai he was difficult and contentious, insistent on imposing his will on theirs, to the Dominicans he was the model of cooperativeness. Told that it was a tradition to eviscerate the church, he replied, “No problem! We’ll eviscerate the church.” When the monastery was under construction, the brothers were living nearby in a château. The architect “thought of us as his children,” giving “a very warm welcome” and making them feel “like real friends.”10

Ducret was keenly aware that Le Corbusier had many adversaries. He felt that if others deemed the architect cold, this was because Le Corbusier was a polemicist: “His calcification was the result of people not understanding him.” With the Dominican brothers, he was “very warm, very friendly, very close.”11 The architect in his top hat and bow tie and double-breasted suit enjoyed an easy rapport with the monks in their austere white robes.

Le Corbusier arrived for the inauguration of La Tourette on October 19, 1960, the day before the ceremony. He spent the night in one of the cells. Many of the Dominicans observed him that evening and the following morning, walking around alone, pacing up and down the corridors that linked the private and public areas. With a meter-long measuring stick in his hand, he busily measured everything, noting the dimensions of each small element, confirming their accuracy and speaking little.

In the morning, before the actual ceremony, Brother Ducret accompanied the architect on his first visit to the church since it had been completed. The Dominican opened the large pivoting panel that separated the church from the low-ceilinged dark corridor. The tall and cavernous space, flooded with the light of the sky, was revealed. “A wall on hinges: it is a miracle,” observed Ducret, forty years after the opening, having opened and shut this wondrous device for most of his lifetime. He never forgot that, as the wall swung open, Le Corbusier looked in and simply whispered into his ear, “Bravo.”12

THE EVENTS of the inaugural ceremonies included a high mass in which the eucharist was distributed. The Most Holy Reverend Father Brown, master of the Order of Preaching Friars, was the first speaker. Brown, an Irishman who did not know much about architecture, had been a friend of Couturier’s. He thanked Le Corbusier, in simple language, for making a building in which one could study and pray: “I am not an artist, and I perhaps lack the aptitudes necessary to judge the great virtues of this house, but I am certain, Monsieur Le Corbusier, that you are giving us a monastery which can serve for many long years, can worthily serve the purposes of the Order, the apostolic purpose of the Order.”13 Others speakers followed, mainly with prayers. Le Corbusier had tears streaming down his face throughout the ceremony.

Afterward, during the repast in the refectory, Cardinal Gerlier of Lyon lectured at length. Then, he addressed a toast to Le Corbusier. The cardinal admitted that he had initially had many reservations about the architect’s work. But over the years he had come to see that Le Corbusier’s purpose was above all the mass that would be celebrated here.

The cardinal also allowed, “Then I discovered that you were friendly, that you could be contradicted, that you could even be teased. Yet someone had told me ‘Watch out, Le Corbusier doesn’t like jokes.’ And I say to that person—he is listening to me now—‘You are wrong.’ And I am glad of that, for I have no great esteem for people who do not enjoy a joke.” The cardinal went on to say that he would leave Eveux happy that day because Le Corbusier had “the worship of spirituality which gives his works their true value.”14

IN THE COURSE of the opening, Le Corbusier acknowledged Xenakis and Gardien, both of whom were present. Although he had never apologized for the Philips palaver—or considered himself at fault—he emphasized the importance of such marvelous collaborators, while, as usual, mentioning his foes: “This is one of the joyous moments of our difficult profession: to find one’s friends among those who know what they are talking about, which is to say, among those who execute, though many enemies oppose their progress, whatever it may be, even without knowing what it concerns, without having seen anything, without knowing anything at all!”

In the sanctuary of Jesus Christ, Le Corbusier’s sense of martyrdom was accentuated. At least for once, however, it was in the happy context of felicitous partnership. And the hard facts of extreme financial limitations had been nothing more than an obstacle to be surmounted: “The house was built under conditions of poverty (to evoke that implacable aspect of economy), which find in me a man trained in those useful Indian gymnastics.”

Le Corbusier also took up one of the elements of the monastic complex others might find problematic: its sound quality. “It is possible for poor acoustics to adapt to the liturgy,” he said. “The liturgy accepts them. So many churches have such poor acoustics that we confuse poor acoustics with the liturgy itself. This creates that echoing noise, that mystery, that confusion which occasionally charms. Here you confront acoustics that are of great purity.”15

Le Corbusier’s declarations that day were a mix of audacity, crankiness, originality, and pure sacrilege: “Granted that I have, perhaps, a certain flair…. If you want to be kind and show sympathy to your poor devil of an architect, it is by formally refusing any gift concerning windows and images and statues, which will ruin the entire enterprise. These are truly things of which there is no need. Note that the architectural work suffices…. Yes, it does suffice, it suffices amply.”16 It was as if a descendant of the Cathars was avenging the conquerors.

The Dominicans had, in fact, agreed in advance to Le Corbusier’s program by letting the architecture speak without the distractions of the traditional liturgical objects to which they were accustomed. Now, with unabashed boastfulness and repeatedly using his most beloved adjective to conjure a plenitude too great to be expressed, the architect told the inhabitants of this building what he had given them in return: “Proportion is an ineffable thing. I am the inventor of the expression: ‘ineffable space,’ which is a reality I have discovered in the course of my work. When a building achieves its maximum of intensity, of proportion, of quality of execution, of perfection, there occurs a phenomenon of ineffable space…which does not depend on dimensions but on the quality of perfection. That is the domain of the ineffable.”17

Le Corbusier then looked at the cardinal and amplified on his spiritual intentions without pretending to a false religiosity. If for the opening of Ronchamp he had wanted his mother and brother to appear Catholic, at La Tourette he was known to be an atheist—or at least a nonbeliever in the Dominican sense. The public awareness of his Protestantism, as well as his own emotions that day, led him to reveal his true faith. He declared his respect for organized religion even if he did not practice it and emphasized the passionate belief system whereby he linked the acts of building and worshipping.

Le Corbusier made the connections between the tactile, the visual, and the spiritual, and he voiced his faith in the richness of the earth and his love for human beings of all cultures.

I shall add only this word: this morning’s ceremony, that ritual High Mass of the earliest days of your Order, that grandiose thing that stages High and Low, as the Chinese say, Heaven and Earth, with men and this present work, this monastery, this substantial structure, so full of finesse and so charged with sensibility to the limits of eye and hand. An encounter which for me is the joy of this day and perhaps much more still. I can say, in all simplicity: this architecture is valid!

Your eminence, I thank you for having come here today. I hope that our rough concrete and whitewash can reveal to you that our sensibilities, nonetheless, are acute and fine underneath.18

Le Corbusier’s remarks were eventually published. But there was another sentence that the architect uttered extemporaneously, that was not part of the programmed script. Roland Ducret never forgot it: “He has raised the earth to meet the…” At that moment, Brother Ducret remembered, Le Corbusier suddenly hesitated. “And then he stammered—he couldn’t find the word—and said, ‘celestial.’”19

7

After the inauguration, Le Corbusier issued one of his humblest public statements, as if Couturier’s personality had infused his own.

Architecture is a vase. My reward for eight years of labor is to have seen the highest things grow and develop within that vase. The ceremony whereby the Catholic Church took possession of the monastery the morning of the inauguration was a very precise and very beautiful moment.

I have tried to create a site of meditation, of research, and of prayer for the Preaching Friars. The human resonances of this problem have guided our work. An unexpected adventure—like that of Ronchamp. I imagined the forms, the contacts, the circuits necessary for prayer, the liturgy, meditation, and study to be at ease in this house. My profession is to house men. Here the question was to house men of religion, trying to give them what today’s men need most: silence and peace. These priests, in this silence, locate God. This monastery of raw concrete is a work of love. It does not speak of itself. It lives on its interior. It is in the interior that the essential occurs.20

The result of his submission to a scheme, his approach to workmanship, respect for the client, and the goal of serenity and contemplation are evident on the hilltop near Lyon.

8

An article published in the Lyon newspaper the day after the inauguration gives a vivid description of Le Corbusier: “Le Corbusier is here, anxious, timid, rather embarrassed by all the prominent figures around him proclaiming their admiration. His lucid eyes assess the quality of the volumes, the alternating hollows and swellings, the bold outline of the structures, the modulations of the lines, the cohesion of the forms, etc., etc., and perhaps he remembers that Charterhouse of Ema, already so distant, where in his youth his human vocation as a builder was affirmed…. In the first row of those present M. Le Corbusier had on his right M. the Mayor of Lyon, Louis Pradel, and on his left Messrs. Gardien, Xenakis, Burdin, Ducret, Brisac, Messrs. Rostogniat, president of the Council of the Order of Architects, Foch d’Hauthuille, Maître Chaine. etc., etc…. Le Corbusier uttered a few words muffled by emotion, and it was apparent that the impassive architect, solid and loyal as the pillars of his Unités d’Habitation, had been deeply touched. ‘I have known many struggles, disappointments, attacks in my life,’ he explained…. ‘This morning I found my finest reward in discovering that my work could bring into play the High and the Low, man and spirituality, and could develop the most exalting regions of the human soul without the builder’s realizing it. Behind these simple and rough surfaces there is, do not doubt it, a rather fine sensibility.’ Yes! there, on the walls of La Tourette, is the human and unmasked message of Le Corbusier.”21

The architect could not quite master his voice that day. The man who usually spoke with an arch tonality and complete assuredness was for once “a little quavery.” What was evident to astute observers was Le Corbusier’s “very great sense of the spiritual, or transcendence.”22

9

In a statement he issued once La Tourette was in use, Le Corbusier was proud to point out the possible unpopularity of the design from the start and the Icarus-like risk he had taken: “You have a building…which…touches the ground as it may. This is a thing which is not to everyone’s liking. It is an original aspect of this very original monastery.”23

Initially, he had intended the cloisters to be on the roof, facing the spectacle of nature: “I think you’ve all been on the roof and you’ve seen how beautiful it is. It is beautiful because you don’t see it. You know, with me there will always be paradoxes.” But then he had decided that if he put the cloisters on the roof they would be so beautiful that the monks would lose sight of the real goals of the religious life. It would distract them from the hard realities of their interior lives. “The pleasures of sky and clouds are perhaps too easy,” Le Corbusier had determined. Instead, he put the cloisters below, with the idea that access to the roof could be granted on rare occasions.

With that focus on the psychological and spiritual impact, he made the church steeple the highest point of the assemblage and devoted himself to the issue of letting light in below. “Emotion comes from what the eyes see, which is to say: the volumes; from what the body receives by the impression or the pressure of the walls on oneself; and then from what the lighting affords you, either in its intensity or in its delicacy, according to the sites where it is produced.”24

10

Five years following the opening of La Tourette, Le Corbusier’s body was brought to the monastery. His funeral cortege stopped at the site en route from Roquebrune-Cap-Martin to Paris. The architect’s closed casket spent the night of September 2, 1965, in the austere cavern of the church.

Paris Match reported, “In the courtyard of the Louvre, in the presence of thousands of Parisians, there was the brilliance of such official ceremonies. But, on the road which the funeral procession took from Roquebrune, there was a discreet halt. This was at the Monastery of La Tourette which he had built and which today is regarded as one of his masterpieces. His coffin was set down before the altar. Yet he was not a Catholic. When asked ‘Do you believe in God?’ he answered ‘I’m available, I’m searching.’ The Benedictines [sic] lined up in front of the remains of this man who had built their cloister and kept watch all through the night.”25

It was as if Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had been returned to the rustic silo where he had lived on the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds as a young man. All night long, on this final visit with some of the truest devotees of his architecture, the Dominican brothers prayed around Le Corbusier’s body in its sealed casket, yet again giving religion to a Cathar.