LIX

1

In the years following Yvonne’s death, Le Corbusier’s creative impulses declined. Their marriage would have suited few people, but his role as peripatetic caretaker had given him what he needed at home to be Le Corbusier in the world. With Yvonne gone, he began to lose his creative spark, even if he was technically very busy.

He took up painting again. He no longer had the luxury of being able to open the door of his cavernous studio on rue Nungesser-et-Coli to find his wife two rooms away crumbling saffron into a bouillabaisse or wanting him at her side for a pastis, but in his solitude, he threw himself into the making of large enamel plaques, six of them all at once. He would paint away his emptiness.

LE CORBUSIER returned to England to be anointed doctor honoris causa by the faculty of law at Cambridge University. For the man who had once caused his father serious worry about his schoolwork and who had never received a degree in architecture, there was a certain satisfaction in the endorsement. If the speech about him fell short of likening him to Christ carrying the cross to Calvary, it still put him in impressive company: “He shares with Cicero the view that utility is the mother of dignity. His relation to Leonardo derives from the fact that he too envisages the principles of mechanics with a painter’s and a sculptor’s eye. To those who seek the ‘divine proportion,’ he has given the Modulor, based on the measurements of a man whose height is 1 m 85…. Not only France but India, Moscow, and North and South America testify to his importance, so that in his regard we may cite, with some modification, this line of Virgil: ‘What region of this earth is not full of the work of this man!’”1

His response to this praise was plain: “In order to arrive at this ‘certain level,’ let us suppose a level meter of a thousand millimeters, whereupon we must begin with the first millimeter, the second millimeter, etc…. regularly and in the order of things. You soon realize how serious, how difficult it is, how steadily you must persevere, how much confidence you must have, and energy to forge ahead.”2 The lessons of the watch engraver and piano teacher were imbued in him still: his father’s insistence on effective labor and his mother’s counsel always to do all tasks right away.

After the morning ceremony that required his wearing a cap and gown for three hours, he derided such academic formality as a nonsensical waste of time. In retrospect, it became “playing the fool for 3 hours.”3 The architect subsequently declined invitations for honorary degrees at Harvard University and at a new university in Brasília. But even if the ceremony at Cambridge had been three hours of nonsense, Le Corbusier was proud of the tribute and eventually reprinted it as part of his official biography.

2

His mother’s death less than three years after Yvonne’s had left Le Corbusier bereft and even more alone. No one could rival these women in assuaging his solitude, in making him feel that with all the unchartable variables of his quirky personality he had a true connection to someone else. Even Marguerite Tjader Harris had become so devoted to her nuns in Connecticut that she seemed spiritually as well as geographically distant.

It was not that he lacked admirers. Women, especially, still found Le Corbusier charismatic. The gallery owner Denise René was enthralled when traveling with him to exhibitions in Bern and Venice and observed that he completely mesmerized his companions by talking about the sources of the local architecture. When René was with him in Stockholm, a woman told Le Corbusier she simply wanted to breathe the same air as him: “The very elegant architect—tall, a dreamer, a strong presence, successful with women—replied by telling her to calm down.”4

Heidi Weber, a Zurich decorator who had a gallery to show interior design, became so devoted to Le Corbusier that she swapped her car for a collage by him and then put on an exhibition of his paintings in her studio where, when nothing sold, she bought all the work herself without telling him who the client was.

His mother’s passing was a fresh reminder of the inevitability of death, and Le Corbusier began to prepare for the aftermath of his own life. In August 1960, while puttering around the cabanon, he developed with Jean Petit the idea of a Fondation Le Corbusier. After his death, it would house his work, his collections, and even his personal possessions. It would be located in the villa he had designed for Albert and Lotti but would also preserve the apartment at rue Nungesser-et-Coli, as well as the Villa La Roche, which Raoul La Roche offered for this purpose. This organization would manage the archives the architect had long hoarded with what he termed “my old-fox order.” But Le Corbusier was concerned more with young people and those who would profit from his legacy than with issues of preservation. He intended to create a travel scholarship for worthy recipients “who want to learn to see.”5

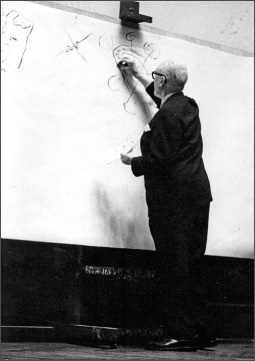

The architect was delighted when he gave a lecture in the largest amphitheatre at the Sorbonne, with seating for 3,500, to find that a thousand students beyond that capacity clamored for seats. To the new generation, he voiced his ideals, exalting the highest moral standards while using American materialism as an example of the opposite: “I want to address here the man and the woman, which is to say, the living beings who have a heart, a sensibility, a mind, some courage perhaps, and who desire to see things as they are. There are possibilities—a Cadillac, of course, that’s one, but there is the other possibility—to have the satisfaction of one’s own conscience.”6

Sketching during a lecture at the Sorbonne, February 1960

The office provided some welcome distractions after his mother’s death. Le Corbusier designed a museum for Chandigarh—a large structure similar to the one he had made in Ahmedabad, a crisp container for Indian art from ancient times to the present. There were new proposals for churches, apartment buildings, an embassy, a hotel, and a factory—the majority in France and Switzerland, but some in locations from Egypt to Chad to Brasília to Oakland, California. All these projects met the usual fate, but they kept Le Corbusier and his staff busy. In 1963, the Olivetti company, with which Le Corbusier had initially tried to work nearly thirty years earlier, asked the architect to design a laboratory and factory for electronic calculators. These mathematical tools, evoking both the timepieces of his youth and the Modulor, greatly appealed to Le Corbusier, and he liked the idea of building the place where they would be developed and assembled. Moreover, although he was no longer alive, Adriano Olivetti, whose name was synonymous with the aesthetic refinement that was just then catapulting Italy to the forefront of elegant design, had been “not only an industrialist in love with beauty, but also an organizer of our epoch.”7 But nothing came of the project.

Le Corbusier was proud to be busy enough to have to turn down work, especially from potentially prestigious clients. Prince Moulay Hassan of Morocco summoned him to Rabat to consider taking charge of the reconstruction of Agadir, which had been partially destroyed by an earthquake; the architect declined, saying he was too consumed by a plan for the Meuse valley, among other urban schemes. He could refuse such offers because there was something in the air that warranted his utmost concentration. At last, Le Corbusier had—or so he believed—a major project in the heart of Paris.

This would be his first structure at the city’s epicenter and thus more significant than the Cité de Refuge or the two pavilions at the Cité Universitaire. The new Paris undertaking was similar in scale to the three great buildings about which he still felt slighted: the unrealized League of Nations in Geneva, the architectural assemblage for Moscow that had been reduced to a single structure, and the stolen UN complex. He had one more chance of influencing the look of the world as profoundly as did the Parthenon, Notre-Dame, and the Milan Duomo. Again, he was full of hope.

3

The plan was for a hotel and cultural center to be built at the Gare d’Orsay, the large nineteenth-century train station overlooking the Seine on the opposite side of the river from the Tuileries. The main stipulation of the undertaking was that nothing disrupt the reigning aesthetics, but there were no impositions about the choice of materials. Le Corbusier was thrilled at the possibility of the views he would be able to provide of sights he had deemed exquisite ever since his early years in a garret—“the unexpected poem of Sacré-Coeur, the splendor of Les Invalides, the spirit of the Eiffel Tower…a feast for the mind and for the eyes.”8 His relationship with the city he had known for half a century was as complex as that of a child with a parent he both loves and wants to destroy, but he had come to worship the poetry of Paris’s landmarks more than ever.

He was thrilled to design a place where people would gather en masse; he would give them the benefits of modern technology: “Actually what I’m talking about is a cultural center for congresses, exhibitions, music, performances, lectures, provided with all the latest equipment for traffic, for acoustics, for ventilation and fresh air, and impeccably connected with the totality of Paris by water, by Métro, by streets, and (perhaps) by the (express) train to Orly, now the main wharf of Paris, not a seaport but an airport.”9 The enthusiasm of this run-on sentence recalled the happiest days of his past.

Yet again, Le Corbusier would seize the moment: “The construction methods of modern times permit the creation of a prodigious instrument of emotion. That is the opportunity Paris has, if Paris realizes the desire to ‘continue’ and not to sacrifice to sentimentality the enormous historical landscape existing on this site. It is by a fervent love for Paris on the part of the promoters of this project that a goal so accessible on the one hand, but also so lofty on the other, can be attained.”10 Le Corbusier’s manic ecstasy overtook him when he thought he could vanquish his enemies and give the world something unprecedented.

Not that he had stopped smarting over previous Parisian failures. “My name has always frightened Paris,” he announced.11 He would not forget, or let others forget, that his stadium design of 1937 for one hundred thousand had been summarily rejected, while now its clones were popping up everywhere. Perhaps the same ugly fate would happen with the great complex on the Seine. But for the moment he was floating on air.

THE PLAN CALLED for a hotel with twenty-five floors of rooms and a large public space for airplane companies, boutiques, and a bank. All the commercial enterprises would be in a giant slab on pilotis parallel to the Seine, with the powerful skyscraper attached to a congress hall and cultural center. The Gare d’Orsay would have been torn down.

Le Corbusier credited himself with “a spirit of absolute loyalty, of total constructive organic rigor, and with the desire to provide a decisive manifestation of architecture at the hour when Paris must be wrested from the profiteers or from the mindless.”12 So he claimed, but there are few among us who can regret that this project failed to become a reality. His proposal would have brought the worst aspects of modern Parisian architecture—exemplified today by buildings like the Tower of Montparnasse and the Australian embassy—into that magnificent region where, on one side of the Seine, some of the most charming streets of the faubourg St. Germain remain a bastion of small-scale architecture, and, on the other side, the Tuileries and the Louvre exert their quiet splendor. Not only would the scale of the structures proposed by Le Corbusier have been a disaster, but his skyscraper did not even have the charm or excitement of most of his work. It resembled a gigantic, merciless grate.

Le Corbusier’s office prepared a photo of central Paris with the model of this massive block superimposed. It’s not hard to understand why the city administration took the idea no further after seeing this mock-up. The shadows Le Corbusier’s project would have cast over the seventh arrondissement would have committed the very offense the architect so loathed in New York skyscrapers. His towering hotel would have put people in permanent shade and deprived them of direct sunlight.

For all his genius, Le Corbusier remained completely insensitive to certain aspects of human existence. His fervent faith in his own way of seeing blinded him to the wish of people to retain what they most cherish in their everyday lives. The old Gare d’Orsay is a building of dubious architectural merit, but at least its ultimate renovation did not destroy the heart of a beautiful metropolis.

4

Not everything came to a halt. In Zurich, Heidi Weber persuaded Le Corbusier to do more printmaking and to design a villa on the lake; intended mainly for the display of his graphic work, it was completed in 1967. The architect also had some amusing forays in the design world. One of his tapestries was hung in the great London fish restaurant Prunier, for which he also designed china.

In 1961, Le Corbusier overcame his ambivalence about official accolades sufficiently to travel to New York to receive a doctorate at Columbia University and to go on to Philadelphia to be awarded the gold medal of the American Institute of Architects. The advance directives from the dean of the Columbia University School of Architecture, Charles Colbert, must have afforded the architect some satisfaction, given his previous slights in America. They stated that events “will conform entirely to [Le Corbusier’s] wishes, which we will determine upon his arrival.”13 At Columbia, the architect was to receive honors and speak “with the entire audience anticipating your words of direction and wisdom.”14 Le Corbusier circled “direction” and “wisdom.”

When Le Corbusier arrived at Idlewild Airport on April 25, he was greeted by the entire student body of the architecture school and taken by limousine to the Plaza Hotel. Then, at the magisterial campus on Morning-side Heights, he was awarded a doctorate honoris causa. The statement read: “Charles Edouard Le Corbusier, eminent theoretician, profound architectural innovator, inventor of the skyscraper-studded park, you have resolutely proclaimed Man’s right to an environment of increased amenities. Through your architecture you have sought to bring Man and the Forces of Nature into beneficent accord. In a technical age you have endeavored to produce a Universal Man, a concept designed to give unity and validity to creative achievement in those broad fields of the Arts upon which your abundant energies have been so productively expended.”15

AS ALWAYS, however, there were areas of conflict. In 1962, Pierre Jeanneret wrote Le Corbusier that Hindustan Machine Tools, a large Indian company, wanted to create an “industrial city” next to Chandigarh. It was to go between the Punjore Gardens, a lush outdoor space, and the main cement factory.

Enraged, Le Corbusier wrote to Nehru. Knowing that the prime minister was busy because of upcoming elections, he apologized for the intrusion, but this potentially disastrous development required immediate action. Yet again, the forces of good and evil were as clearly defined as in a Last Judgment: “It is revolting to annihilate the immediate approaches to Chandigarh by an industrial city, and this at the very moment when the theory of the ‘Industrial Linear City’ appears as my social, political, geographical, demographical solution, responding at last to the modern conjuncture…. I am speaking to you as seriously, as profoundly as I know how. At the moment when Chandigarh appears as a site created for the good of mankind, here comes the devil to meddle with it, instituting this hideous canker on the flanks of this city!” Le Corbusier then tried his familiar tactic of false humility: “I am boring you. I am assailing you with complex arguments, each linked to all the others. And you are in the midst of elections at this very moment. I am embarrassed.”16

At the end of the year, the architect wrote a letter to K. S. Narang, the secretary to the government of Punjab, which he copied to Nehru with a cover letter. Le Corbusier’s contract as architectural advisor to Chandigarh had just been renewed, for the upcoming two years. “I accept this,” he wrote, “but I must tell you that I shall do so gratis: without honorarium and without vacations. I am happy to offer this to India, a country I love.”17 He would come at least once a year to give advice and oversee and correct work; they would need to pay only for his round-trip transportation with Air India.

At the same time, he meticulously listed all the expenses that had not been covered for work to date. He had received nothing for his twenty-first and twenty-second trips to the new city, the last that June, and was now owed a total of 27,200 rupees. The accounting recalled Georges Jeanneret’s diaries about cheese prices, but the conclusion was quite unlike anything Le Corbusier’s father would have written: “I am pleased, then, to make you a gift of all these expenses incurred for Chandigarh and which are now added to my gratis service as Government Architectural Advisor. Perhaps you will be grateful for this gesture.”18

In his cover letter to Nehru, Le Corbusier wrote, “I am making an important gift to India. Believe me, dear Mr. Nehru, I am making it with all my heart and in total sympathy with you. I am happy to contribute my obol to the financial appeal made to India at this difficult epoch for your country.”19 How like Le Corbusier to refer to the ancient Greek coin—worth one sixth of a drachma—as if he were building another Parthenon.

Nehru’s response was cool. To begin with, the prime minister wrote that he would have answered sooner if Le Corbusier’s office had not dispatched the letter written in December almost a month later. Nehru continued: “I appreciate your offer and gift to India.”20 But he said nothing more; there probably was another side to the story.

Perhaps the signature of a head of state was sufficient recompense for Le Corbusier. His weakness for the highest levels of officialdom was never ending. When another Expo Le Corbusier opened at Le Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, Le Corbusier was aware of the contrast to the opening of his previous show there: “Père Le Corbusier is respected now,” he observed.21 Not only were André Malraux and a bevy of other government ministers in evidence, but they actually looked at the work, with the esteemed minister of culture commenting specifically on the precision of the early Purist paintings.

Yet the architect was painfully aware that there was not even a small Unité d’Habitation in Paris—although he had now built a substantial one in Firminy, near the city of Saint-Etienne. Success in the capital still eluded him.

5

For the opening of the General Assembly at Chandigarh, Le Corbusier made another enormous enameled door, the size of a wall, that swung on its middle axis. With Jean Petit’s help, he spent a dozen days in the factory in Luynes fabricating 110 square meters of enamel plaques—a substantial leap over the eighteen square meters for Ronchamp. They were baked at a temperature of eight hundred degrees Celsius—a fact that thrilled Le Corbusier.

He and Jean Petit presented those enamel plaques as a further gift to Jawaharlal Nehru specifically. The gesture testified to the architect’s profound appreciation for what the Indian leader had had him do—with, he pointed out, one fifth of the means available in other places.

At the same time, as always, a further quest mattered more than the victory in hand. Knowing that Nehru himself would be present at the opening, Le Corbusier wanted to use the occasion to lay the foundation stone for the Open Hand. Le Corbusier had determined exactly where it would stand—near the assembly and the other buildings, with the Himalayas in profile behind it.

Even more than previously, Le Corbusier saw his monument as having unparalleled value to the world at large. It was his last hope of saving human civilization. Writing Nehru on June 26, 1963, at a time of heightened cold-war tension, the architect declared, “The modern world is torn between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. The Asiatic East is gathering together.” He believed that the location of the Open Hand, facing the Himalayas, was pivotal. “At this precise moment there could not be a more significant place.”22

The sculpture was a gesture of welcome that signified an open heart on the part of all people to all people. He concluded his entreaty, “Dear Mr. Nehru, the symbol of the ‘Open Hand’ has a particular significance for me in the management of my life devoted up to now to the equipment of the machinist civilization. I feel with a deep instinct that India is the country where this sign must be dressed—India, which is for us Occidentals since four thousand years, the place of the highest trend of thought.”23

6

Le Corbusier had almost resumed his former pace. He was no longer creating architecture with the same verve as when Yvonne and his mother had been alive, but again he had a purpose. He made urban plans for Venice and went to Brasília to plan the French embassy there. He found this capital city by his colleagues Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer inventive, courageous, and optimistic. “It speaks to the heart,” he said.24 Le Corbusier’s endorsement and generosity gave Niemeyer a boost, which the hundred-year-old architect still prizes.25

In 1962, Le Corbusier was asked to show his paintings in Barcelona. Since all of his major paintings had been commandeered for his retrospective at the Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris, he declined. But he proposed an alternative, again writing about himself in the third person: “He doesn’t feel that he’s a jack-of-all-trades, but quite simply a free man, never having recognized the academy and having opposed the academy.” He reminded the Barcelona architects who had invited him that the first lecture he had given in their city, in 1929, was called “To Liberate Oneself from the Academic Spirit.”26 To celebrate this liberation, Le Corbusier decided to assemble fifty photographic documents—selected from twenty thousand—that showed enlarged details of his work.

For the scale of these images, the architect had chosen “the measurement of 2 m 26, fruit of the double square ‘113 × 113’ bearing certain proportions discovered one day and baptized ‘The Modulor.’ The ‘Modulor’ is a tool offered gratis, the patent having been placed in the public domain…. Such a resource, in the globalization which has seized the world at present, is a factor of peace—while leaving undisturbed the various systems of assigning dimension such as inch/foot, meter, etc.”

He continued in a rampage. This device he had given to the world free of expense and that would have assured universal peace had been rejected by fools: “But the numbskulls and naughty boys, and those who are always ready and willing to say ‘no!’ (in this instance, they are idiots), declare that this is a strictly personal and arbitrary point of view. Upon the invention of the Modulor, this capacity for globalization was regarded as stateless, as antinational, and rejected with horror by those who have no notion what is involved.”27 His idea for a grand-summation photo mural at the Swiss Pavilion had also been mercilessly attacked, he pointed out. The Gazette de Lausanne had laced into the mural and called it a “corruption of minors” before Hitler’s minions had destroyed it during the occupation—a detail he provided without mention of where he had been at the time.

Now, at last, Barcelona had accorded him the opportunity of righting these setbacks. He was extremely grateful. Le Corbusier relished putting together all these oversized photos of his urban schemes, architecture, paintings, murals, and drawings and having them go on public view.

The mural was in black and white. Thus, like some television in that same era, it demanded that viewers imagine the nonexistent hues. That necessity appealed to Le Corbusier. He cherished the ability of the human mind to transpose what it saw: “Color is the sign of life, the bearer of life. The world that opens before us today is becoming polychrome, has become polychrome. Open your eyes to the many colors of the automobiles, which not so long ago were all black.”28 To look at a black-and-white mural and mentally conjure vibrant hues required viewers to make a worthy leap. And it realized one of Le Corbusier’s main goals: to get people engaged by using their eyes and imagination.

7

In 1963, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts was inaugurated at Harvard University. It was the first building credited to Le Corbusier in America and his last major structure. The intention of the building was the integration of the arts into general education at Harvard; the Carpenter Center was meant to beckon students from every discipline, with “the sole purpose to convey to present generations the desire and the need to conjugate the labor of hands and head, which is Le Corbusier’s most important social virtue.”29

Le Corbusier’s longtime colleague José Luis Sert was the project supervisor. Le Corbusier himself spent only three days on location in the course of the entire design and construction, on a trip that had a shaky start. When, in June 1960, the architect had gone to the American embassy on avenue Gabriel in Paris to get his visa, he was asked if he had ever been a member of the Communist Party. He had not, but he deemed the question unseemly and proposed a meeting with the ambassador. The request was granted, and Le Corbusier asked Jean Petit to accompany him. Petit described the encounter: “Le Corbusier announces straight off that he is unwilling to answer any question about his opinions and his private life. He is a world-renowned architect, that is the sole useful answer to useless questions. The ambassador is charming and amiably accepts the architect’s unmannerly bluntness.”30

Le Corbusier then made the trip. He flew first-class on Pan Am, taking with him the maquette his office had already prepared, although he had not seen the site firsthand. When he arrived in Cambridge, he realized that, relative to the other structures, the small site Harvard had allotted showed how far the university really was from wanting the arts to have parity with law and history.

Nonetheless, what Le Corbusier achieved on the compressed lot in the middle of a rectangular block of neo-Classical buildings has considerable impact. The bold ramps, cantilevered ovoids, and deep brises-soleil are a strong statement of imagination and newness in contrast to the traditionalist red bricks and brownstone of the rest of the university.

Yet the Carpenter Center suffers from some of the shortcomings that often befell Le Corbusier’s presence in America: a certain discomfort, a look of struggle, even confusion. For the building’s opening in May 1963, Le Corbusier wrote Harvard president Nathan Pusey that his doctor would not permit him to attend. He neglected to say that he followed the doctor’s orders only when it suited him. On one level, the architect had reconciled his relationship to the country that had once fueled his greatest optimism. On another, he deliberately kept his distance from the place where he had incurred some of his deepest wounds, and where he felt slighted still.

THE YEAR the Carpenter Center opened, Le Corbusier had good reasons to have his sights focused elsewhere. As minister of cultural affairs, Malraux was becoming more and more powerful and also increasingly loyal to the architect. He now asked Le Corbusier to design a museum of the twentieth century, to be constructed at the Rond-Point de la Défense, a forty-five-hectare parcel on the outskirts of Paris.

Le Corbusier again took up the museum idea he had realized in compromised forms in Tokyo, Ahmedabad, and Chandigarh. His excitement was palpable. He compared the idea of bringing it into existence to what he considered the ultimate act of creation: “Before giving birth, a woman doesn’t know the color of her child’s hair.”31

But soon Le Corbusier and his staff came to the conclusion that the site was “devoid of all landscape charm” and proposed a different location in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Le Corbusier also recommended that the city consider destroying both the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais—buildings he had never liked—to fulfill Malraux’s request for a new museum. When he did not succeed in shifting the site to either true countryside or the city center, he abandoned the project.

STILL, LE CORBUSIER’S life had its sweet moments. In the spring of 1963, when he was offered a doctorate honoris causa by the University of Geneva, he was convinced that the main reason was that he was owed credit for the “prime” project for the League of Nations thirty years earlier. The architect wrote “Bravo!” on the letter that announced this redress of an old wrong.32 While explaining that every day he turned down requests to travel, in this instance he accepted. His one stipulation was that he had to wear a suit, rather than evening clothes, at the celebratory banquet. The former Charles-Edouard Jeanneret enjoyed returning to Switzerland on his own terms. He stayed at the elegant Hotel Richmond—a distinction, given his many defeats at the hands of some of the League of Nations officials who had once been at home there.

Then the city of Florence organized a large Le Corbusier exhibition and gave him the gold medal of the city, declaring him the “greatest urbanist architect of our epoch.”33 The University of Florence was yet another institution to offer him a degree. In response, Le Corbusier wrote the French consul to the Italian city explaining that he had not requested the degree and had already received many such honors—he attached a list—but that, nonetheless, he would gladly be present at a ceremony if it could take place in Paris. The event occurred that December at the Italian embassy in the French capital: the mountain came to Mohammed.

That August, in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, where he lived mostly in solitude even with the Rebutatos next door, Le Corbusier again reread Don Quixote. In his copy of the book, covered with the hide of his beloved Pinceau, he found a penciled note he had written nearly forty years earlier. It recorded a dialogue between himself and the young woman who had recently moved into his apartment: “Greatness. Von: ‘And that time I walked from Montmartre to the rue Jacob?’ Le Corbusier: ‘But why did you walk all that way?’ Von: ‘Because I didn’t have money for the Métro.’”34

12

With the people he still enjoyed, such as Jacques Hindermeyer and the Rebutatos, Le Corbusier was warm and outgoing; with those who annoyed him, he had become increasingly cantankerous. It was standard fare when Le Corbusier said to the Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo, “I’ve been listening to you, and for a long while I wondered if I was dealing with an imbecile—yes, I was dealing with an imbecile.”35

Those who met Le Corbusier’s brother were struck by the contrast. Albert was “much more affable and agreeable than Le Corbusier, much sweeter” than the “boorish” Edouard.36 When Le Corbusier felt himself contradicted, he would explode, “I’m right! I’m right! I’m right!” The conversation stopped there.

He was despotic at the office. It had long been Le Corbusier’s practice, after returning from his travels, to be furious at what the others had done in his absence, often requiring them to remove their own detailing and restore where a project had been before he left. On one occasion, when a range of buildings and urban plans were in process, he summarily dismissed all his draftsmen.

In February 1960, he sent a letter to his employees: “I have been quite dissatisfied lately with the slow progress of our work. I’ve already spoken to you about this. And I am specifically requesting that you do not begin your tea breaks during the afternoon. You are not to leave the studio. I am making this a specific request, for otherwise bad habits will be established…. Once again, there is a lapse in the production of drawings. What is the reason for this? I am astonished that it has not occurred to grown men like yourselves to establish a program for your work involving the numbering of the presumable plans to be drawn and the indication of the scale…. I am here to give you overall ideas concerning the creation of the work. You are sufficiently adult to take all the necessary initiatives within the parameters of the ideas I have given to you or that you have helped me discover. You are fortunate to be working in a studio characterized by a calm atmosphere. You must understand that I am overwhelmed by work every day including Sunday. Do not ask me to be a studio manager as well. The studio is reduced to a small number of persons. You are individuals, and we do not want to be organized here à l’américaine (a form of organization that does not correspond to the objectives I have in mind)…. You will be good enough to take note of these instructions. I have written them out so that there can be no ambiguity.”37

If someone was up to standards, however, Le Corbusier was exceedingly generous. When Roger Aujame, the young architect who had demonstrated the backstroke to him nearly twenty years earlier in the river near Vézelay, needed a letter of recommendation, the master interviewed him at length and then spent an hour and a half writing it.

Nonetheless, a firsthand account of Le Corbusier written that same year opens with a sentence that reads like a clinical impression of mild autism: “He does not have the open expression and the easy smile of those who readily inspire sympathy; admiration and grace are lacking; the eyes are dull, the voice is flat and uneven.” The author was Maurice Jardot, in his introduction to the architect’s autobiographical My Work. Jardot’s description of Le Corbusier’s “porcupine manner” and his “expostulations, abruptness…aggressiveness, egoism, complacency and…somewhat bleak attitude” was published with the subject’s approval and tacit endorsement.38 Le Corbusier did not mind being seen as difficult so long as he achieved his purposes.

To many people, Le Corbusier seemed “distant; not very smiling or making people at ease…and always in a big hat” he did not waste time or suffer fools, for his sole remaining objective in life was to get buildings and cities made the right way.39 Effectiveness was the imperative. This was why he took the Métro between the office and the rue Nungesser-et-Coli; it was more efficient than a taxi. Similarly, he collected seashells and stones because they succeeded at being what they were.

9

The conclusion of Le Corbusier’s relations with India was not a happy one. On October 26, 1963, the architect sent a telegram to Jawaharlal Nehru: “URGENT stop Dangerous intrigue at Chandigarh against Corbusier and Jeanneret stop Hostility of Secretary Capital Project stop Letter following. LE CORBUSIER.”40

The letter sent that same day explained that Le Corbusier felt he had been slighted. Four days earlier, there had been an opening ceremony for the Bhakra Dam, which he and Pierre had helped design. He had not been invited. Pierre Jeanneret, on the scene in Chandigarh, was reporting “violent hostility” on the part of the new local administration. K. S. Narang, now in charge, was annoyed that Le Corbusier was remaining as a government advisor, even if unpaid. Le Corbusier went on to state his achievements to the prime minister in the same manner with which he had touted his virtues to his mother when she complained of her leaking roof.

Dear Mr Nehru, since twelve years I have made an enormous effort for yourself and Chandigarh. I have created an important “Plan of the City” (town planning) and I have made the plans of the four palaces of the Capitol: High Court, Secretariat, Assembly and Museum of Knowledge. Moreover my intervention in the construction of the Bahkra Dam has been considerable (Power Plant and top of the Dam). This intervention of mine has given Chandigarh a world-wide reputation.

My architecture has universal value (and signification)…but it is not appreciated in certain departments. (There has been considerable criticism in the Legislature on “Le Corbusier and his buildings.”)

You are aware of my deepest respect and friendship for you; since twelve years you are present in my preoccupations. Chandigarh and my other works have placed me at the head of the architectural evolution in the world without leaving my office 35 rue de Sèvres. I have transformed architecture all over the world. It is modest to write in this way!! I am very sorry, please excuse me, but it is a fact.41

The stilted English was a result of the translation someone in his office had made from his French. The errors had been relatively minor thus far. But the translator made a truly unfortunate mistake in Le Corbusier’s conclusion: “I wish to (and I must) complete my work at Chandigarh. I have written that my work would be gratuitous [sic], without any fees (I had informed you of this in my letter dated the 17th December, 1962.) I ask to remain beside you so that Chandigarh should be an Indian landmark.”42

For Nehru’s review, Le Corbusier attached correspondence from Narang and Pierre Jeanneret that made clear the gravity of the situation. Pierre’s letter explained precisely how the Punjab government had terminated Le Corbusier’s role on October 18, 1963. At a time when there were fourteen works still under consideration, both Pierre and Le Corbusier deemed it urgent that Le Corbusier return to Chandigarh—even if the new regime did nothing more than pay for his airplane ticket and accept his continuation of the role he had had for twelve years.

There is no indication that Nehru answered. On November 4, Le Corbusier again wrote the prime minister, this time too impatient to have his letter translated from the French, which, after all, he had discovered Nehru spoke at their very first marvelous meeting, under much happier circumstances: “Dear Mr. Nehru, Forgive me for disturbing you once again. I enclose a photograph of the project for the monument accepted by the Bahkra Dam Committee. This project is unbelievably stupid and horrible. Life is difficult!!! Believe me, dear Mr. Nehru, you have my profound friendship. P.S. If this project reaches the stage of execution, I shall make certain it is published the world over and in all periodicals of the highest reputation. And the world will be dismayed.”43

Again, there was no answer.

With an old man’s trembling hands, the seventy-six-year-old Le Corbusier wrote a last letter to Nehru in March 1964. Even to a distinguished prime minister, he did not bother with a full sentence to start. The message was urgent enough to warrant his telegraphic style: “Dear Monsieur Nehru, troubles and tempests at Chandigarh. Actions have been taken in opposition to us,” he began. Then—treating himself, as he often did, as a subject to be observed—he continued, “Le Corbusier has created a work at Chandigarh that is admired the world over. Pierre Jeanneret as well.” He then reverted to the first person: “I am government advisor. My ideas and plans must be respected.”

Le Corbusier was devastated. As he told the man who had defended him so assiduously in the past, the Indians he had come to know over the previous decade were of “the highest value, morally and professionally.”44 He begged for Nehru’s help.

He never received a response. Today, the world deems Chandigarh among Le Corbusier’s greatest triumphs—for India as well as for the architect personally. To Le Corbusier, it was, in the end, another bitter defeat.