LX

Drowning, of course, drowning is strange, I mean strange for those on shore. It all seems done so discreetly. The onlooker, attention caught by a distant feathery cry, peers out intently but sees nothing of the struggle, the helpless silencing, the awful slow-motion thrashing, the last, long fall into the bottomless and ever-blackening blue. No. All that is to be seen is a moment of white water, and a hand, languidly sinking.

—JOHN BANVILLE, Eclipse

1

In 1955, Le Corbusier had taken Hilary Harris, Marguerite Tjader Harris’s son, into the office at 35 rue de Sèvres as an intern. Twenty years earlier, Hilary had been the six-year-old Toutou who had joined his mother and the architect in driving around New York. In the thirties, whenever Le Corbusier wrote to his American mistress, he almost always included a message to her affable son. Now the boy had become a young man who wanted to study the connections between cinema and architecture. Especially with the Philips Pavilion being planned, there was no better place to explore that relationship, from both an aesthetic and a technical point of view, than the office of his mother’s lover.

Harris returned to America following the internship, but he and Le Corbusier remained in touch. In April 1960, on a trip to Paris, Harris eagerly tried to visit, and he telephoned the studio repeatedly. On the day they were finally supposed to talk, Le Corbusier had a meeting at the Ministry of Construction that lasted longer than anticipated, prompting an explanatory letter from his secretary to “Madame Tjader Harris” in Darien apologizing for the missed encounter with her son.

In the spring of 1961, Marguerite Tjader Harris sent a note to Le Corbusier’s office saying that she had missed seeing him in New York and now was at the Lutétia, half a block from 35 rue de Sèvres. She instructed him to phone on the morning of Tuesday, May 30, to see if they could schedule a rendezvous either at the hotel or somewhere else. She said she wanted to show him photos of her son’s work.

At the bottom of Tjader Harris’s letter, Le Corbusier wrote, “Lunch 24 N-C Friday June 2 1961.”1 Now that Yvonne was no longer alive, the coast was clear.

The following April, Hilary Harris, whose film company had an office on Eighth Avenue in Greenwich Village, wrote Le Corbusier urging him to come by on his next trip to New York so he could show the architect his films and a machine for drawing he was trying to make. Le Corbusier was in India at the time and never made the visit.

Then, at the start of 1963, Marguerite Tjader Harris, on behalf of her son, wrote Le Corbusier about an architectural project far grander, even, than the Gare d’Orsay proposal. Its location was in the middle of Manhattan. The liaison that had begun thirty years earlier now seemed to be leading to one of the greatest projects of Le Corbusier’s life.

Tjader Harris explained it very simply. It was her pleasant duty to offer the seventy-five-year-old Le Corbusier an enormous architectural commission. The site was thirty-five acres on the west side of Manhattan, between Fifty-seventh and Seventy-second streets, along the Hudson River. Le Corbusier would design an entire neighborhood adjacent to Lincoln Center. The powerful Amalgamated Lithographers’ Union was in charge. They had a budget of two hundred and fifty million dollars and wanted to build on 8 percent of the acreage, leaving the rest for parks and “banksides” next to new docks on the river. Apartment buildings, an international student center, stores, a library, and recreational facilities, including a swimming pool and playing fields, were envisaged for the site.

Le Corbusier could thus transform a large part of New York City. The situation was different from his proposals for Paris; little destruction would be required since at that time there were mainly railroad yards on the site.

Le Corbusier made some calculations. On his lover’s typewritten letter, he penciled in the upper left-hand corner

1 are = 100 m2

1 acre = 50 ares = 5000 m2

35 acres = 35 × 5000 = 175 000

In the left-hand margin, he wrote,

250,000,000 × 500 = 1,250,000,000 00 A $ = 490

490 ou 500

725,000 000 000 0002

This is how his aging mind worked: in mathematical sequences, feeling the sheer excitement of large numbers when they demarcated land mass and money. Converting dollars into francs, this, at long last, was the chance for victory in America.

2

Tjader Harris reported that the union president, Edward Swayduck, had been speaking with Hilary about a film on which they hoped to work together. In the course of their conversation, he had raised the subject of this urban center and said he wanted to find an architect. Swayduck greatly admired Le Corbusier already and told Hilary he would love to approach the renowned Swiss but had no idea how to find him.

Swayduck was thrilled when Hilary Harris offered to make the connection. Now the only question was how, when, and where Swayduck and the architect could meet—assuming Le Corbusier had the time and interest for such an encounter.

Tjader Harris provided enticing details. President John F. Kennedy was supposed to visit New York that coming summer to launch the project. Hilary, now a successful filmmaker, was working day and night, which is why his mother had written on his behalf. The son’s dream, beyond negotiating this commission, was to make a film about Le Corbusier’s work in India. In the meantime, he would send Le Corbusier a photo of the site in Manhattan.

Tjader Harris asked Le Corbusier how Swayduck should make his approach and under what conditions the architect would accept an invitation to New York. It was urgent. But after three decades of scheduling trysts, she knew the system. If he couldn’t answer, could his secretary please do so? “From what I understand, you’ll be quite free to do as you like. In friendship, ever, Marguerite.”3

HILARY HARRIS sent Le Corbusier the photo and his own letter the following day to reiterate the seriousness of the offer. The panoramic picture, taken from a low-flying aircraft, showed what was mainly a wasteland a few, blocks from Central Park and the skyscrapers of Gotham that Le Corbusier had first discovered in 1935. “Airview Number 60-741” from the Fairchild Aerial Survey included, among other things, the RCA Building—which Le Corbusier had visited with Marguerite Tjader Harris when Toutou was six years old. One never knew what would lead to what.

3

It took Le Corbusier only a few days to answer:

My dear Hilary,

I was glad to have your news; what a long time it’s been! I received your letter of January 26, 1963, accompanying your mother’s of January 25, discussing the great project between 57th Street and 72nd Street along the Hudson.

I’ve thought the matter over, and reason has convinced me that I cannot concern myself with this business. It is a matter of too great importance for me to follow it in all its technological and administrative details. I’m 75 years old and still in perfect health, but I’m no longer at an age when one can take such enterprises in hand. Add to that the difficulty of the language (English) and American pronunciation, and add further the divergence of conceptions of life and work in general between Americans and Frenchmen. You must find the right man for such a situation. I am not he, or I am no longer he.

The UN building appears in the upper-right corner of your photograph—a bitter memory for me. I worked in New York for 18 months, and my plans were not borrowed but stolen! I am the opposite of a man engaged in financial speculations. I am an artist (an architect and something else besides), and my whole life consists of work, hard, modest, continuous, persevering, and uncomprising work. I’ve never compromised in my entire career. Only the Americans have done so with my UN plans, making them into a demihorror.

Please don’t regard my refusal as a manifestation of ill humor, but let me repeat the factors involved:

My age

The speculative nature of the enterprise

The intervention of “architecture.”

With regard to this last factor: my entire life and the books I have written have manifested it, have entered public opinion, have indeed entered the public domain. Others can utilize it without any objection from me.

It is to this factor that I think you should turn your attention: find a second or third or fourth Le Corbusier. Good luck!

It was generous of you to think of me in this business. I am grateful to you, and you have my thanks.

I hope that you are doing extraordinary things with your film work.

I have the fondest memories of you, and I send you my friendliest sympathies.

Le Corbusier4

THAT SAME DAY, the aging architect wrote his longtime lover at Vikingsborg:

Dearest Friend

You send astonishing news! I thank you for thinking of me with regard to an enterprise of this importance. I have answered your son, Hilary, and enclose a copy of my letter to him.

I am hardly a pessimist, but at my age I am an old pine or an old palm, the choice is yours. (I cite two trees that habitually grow straight.)

You have certainly become what people call one of the great women of the USA: fortune, consideration, and exalted sentiments as a “right-thinking American.” It gives me great pleasure to think of you.

I dream of being able to be armed with my two hands and working at things I am passionately concerned about, but life is too hard for me, and I am compelled to adopt an imperative discipline.

Greet New York for me, whisper that it has kicked me out of the United Nations with a frightful brutality, a gesture it repeated to wrest me away from UNESCO in Paris and reject me by veto. Say what one may and do what one may, there are certain things that cannot be digested! You may think I’ve become a grumbler; the fact is quite the contrary, I maintain the best humor at all times, but it cannot be detected by the naked eye.

With all my friendship.

Le Corbusier5

4

Marguerite Tjader Harris gave Le Corbusier what must have been his dream response. She wrote that he had already changed the world with his work, that he was still “the pioneer.” She spoke to him in his sort of language: he no longer needed to “crack his skull with a mountain of details.” She also stood up to him: “But Le Corbusier, I don’t like your way of referring to me. I am not a ‘right-thinking’ and ‘respectable’ American woman…. Quitethe contrary. What fortune I have I have expended and dispensed in many directions, thus liberating myself from this great burden. I now concentrate on writing and traveling.” She went on to explain that she knew interesting people, not socialites, and assured him that work mattered deeply to her. Finally, she let Le Corbusier know that she would see him again in Paris, “domino volente.”6

A MONTH LATER, Hilary Harris wrote Le Corbusier that the people in charge of the lithographers’ union hoped the architect would reconsider. No one else could realize their dream and do justice to their idealism. Wanting to serve the future of humankind and facilitate world peace, the union officials realized that a central plaza was essential. They wondered if Le Corbusier would at least come up with a master plan—even if he delegated the details of the buildings to others. Again, President Kennedy’s name was invoked. His support, as well as that of the mayor of New York and other city officials, was assured. Le Corbusier would be respected in every way: “The leaders of this enterprise respect and greatly admire your need to work without compromise of any kind…. Is it really too late to expunge your bad memories of New York by making this project achievable in complete independence? The directors have asked me to tell you that they would consider this a supreme gift you could give to New York, to the youth of America and to the youth of all the nations who come here.”7 Harris further suggested that if Le Corbusier still rejected the proposal of his flying across the Atlantic to study the site, then Swayduck would gladly dispatch a delegate to Paris.

Although Swayduck himself then made the trip, the New York project never even reached the stage of sketches, but one can imagine what it might have been. Here Le Corbusier could perhaps have realized one of the inventive cityscapes he had designed for a myriad of locations: his ideal of proud skyscrapers standing on pilotis, joyous buildings for sport and human assembly—the type of structure he had first designed for Moscow—and capacious parks. The architecture would have a look of sheer triumph, and the green spaces would have brought a large public into a natural paradise and offered, inevitably, a sequence of splendid framed vistas.

But Le Corbusier never answered. After March 1963, there was no further communication with either Marguerite Tjader Harris or her son.

5

In 1964, big plans were afloat. Le Corbusier completed the design of the French embassy for which he had visited Brasília. He conceived of the ambassador’s house as an exceptionally handsome elaboration of the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau, with a graceful seven-story circular office building nearby. He also resumed work on the Olivetti calculator plant at Rho, near Milan; it was to be a floating rectangular slab and a longer bowed slab linked by a thin bridge: a futuristic vision that combined the geometric and the organic. In addition, he began the design of a long hospital complex in Venice, and was working on a large congress hall in Strasbourg, where the mayor seemed a perfect client: “Under such favorable conditions, the architect may say that he labors like the Good Lord: total responsibility, integrity, loyalty. It will then be understood that architecture belongs to the realm of passion.”8 And he was designing the pavilion in Zurich.

More proposed commissions sparked interest even if they came to nothing. Fidel Castro asked Le Corbusier to construct a “press building” in Cuba. Jean Martin, with whom the architect had made the enamel door plaques in Luynes, asked him to create “Corbusier” toilets and bidets. Le Corbusier declined with the explanation that “human legs and behinds will not acquire the habit, for over the last 50 years they have become accustomed to the English porcelain shape (Water-Closet),” but he liked the idea, and so would have Yvonne.9

Honors were coming in a flood. There was a large show of his work in Zurich. An exhibition opened in La Chaux-de-Fonds called “De Léopold-Robert à Le Corbusier,” thus linking him with the artist for whom his childhood street had been named. Like many who disparage the power structure, he was happy enough when it applauded him. The architect was now proud to rise yet another notch in French officialdom and be named Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. If his mother had been alive, perhaps she would have attended the ceremony; at least he would have sent her piles of newspaper clippings.

This time, Le Corbusier was even willing to wear his evening clothes. A photograph in the December 20 France-Soir shows him with President Charles de Gaulle—both in their elegant, wide-lapeled dinner jackets leaning toward each other, as a man who opposed Vichy congratulated one who had tried to work within Pétain’s ranks. André Malraux declared, “France pays homage to the world’s greatest architect.”10

But even if the masters of ceremony touted him, endorsement overall was short of what Le Corbusier really wanted. Of all the projects in the office, the only one that was built was the pavilion in Zurich—three years too late for Le Corbusier to see it. When the architect’s friend and colleague Paul Ducret died in September, Le Corbusier wrote, “I do not mourn those who die, death is a beautiful thing when one has lived an active life.”11

6

For a little while longer, however, Le Corbusier trudged along. The office had the usual number of potential projects in 1964—even if none were realized—and, with the start of 1965, the architect devoted himself to the Venice hospital. He had taken it on, he said, out of love for the location; no other city addressed the issues of urban living in the same way as Venice, a place he had adored since 1907.

Le Corbusier designed a sprawling horizontal complex that meandered around and over canals. Most of it was only one story high. It provided rooms and care for 1,200 emergency cases and acutely ill patients. Its complex roof structure equipped every one of the rooms, while windowless, with side skylights that would enable patients to control both the temperature and the amount of sunlight coming in and also give these ill people “the feeling of being pleasantly isolated.”12 How the hospital would really have turned out is another matter. These cell-like rooms without windows at eye level might have felt confining.

Beyond that, as with the Gare d’Orsay cultural center, Le Corbusier wished to impose a building concept that looks as if it has descended from another planet. Extending into the water with its gondola port and laboratories and operating rooms, this behemoth would have borne little relationship to the palazzi and canals and old neighborhoods around it. The architect was better off building in locations like Ronchamp and La Tourette and Chandigarh, where the relationship was between Le Corbusier’s work and nature. When the pairing was between Le Corbusier’s ideas and an existing city, it often became a rivalry the architect had to win. Most people are glad he lost.

7

On July 27, two days before he was to leave for the south of France for his annual holiday, Le Corbusier worked at 35 rue de Sèvres throughout the morning. It was a reversal of his previous routine, but he now found himself too tired to make architecture in the afternoons.

He and his former staff architect Jerzy Soltan visited that day, and they took a taxi to the rue Nungesser-et-Coli to have lunch there. Soltan recalled: “Le Corbusier offered me a drink. The sun was resplendent on the terraces. All sorts of plants were in bloom. Far away, Mount Valerian was vibrating in the summer heat; nearby, bees and flies buzzed around their heads. What will you have? Something light. Perhaps a Dubonnet. And you? Le Corbusier poured himself a double pastis, hardly taking any water. It is a deadly beverage, and I protested mildly. Le Corbusier dismissed my grumbling. He was smiling but serious. As long as he was alive he would not allow himself to be pampered. As long as you live, live with gusto! After luncheon, however, he weakened visibly. Yes, he thought he would lie down. A Mediterranean siesta—nothing more. Kindly, but firmly, he saw me off.”13 It was the following day that the architect took off his shirt in Dr. Hindermeyer’s dining room because of what he described as rats in the plumbing.

A day later, Le Corbusier took a Paris–Nice flight. The air journey was a remarkable improvement over the long treks by car or train of years ago. When he arrived at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, he wrote Albert, “My fatigues are those of a man of fifty.” He described a life in which, without exception, he was at the office at nine every morning—which would have been true if the studio counted as the office. “So, dear friends, brothers, comrades or near relations, let me and my fatigue get the hell out of here.”14

Again, Edouard announced his beliefs to his older brother: “My morality: in life, to be doing. This means, to act in all modesty with exactitude, with precision; an atmosphere favoring the creation of art = modest regularity, continuity, perseverance.”15 Le Corbusier told Albert how happy he was to be at l’Etoile de Mer and how wonderful Thomas Rebutato and his wife were.

Summing things up, the architect voiced his confidence in Albert’s musical talent and assured Albert that his future would be full of successes. As for himself, Le Corbusier had other ambitions: “Myself, I have one hope for life, expressed by a crude phrase: everyone has to croak some day…. Yet it is a hopeful phrase, one which commits a man to choosing life, the one worthwhile choice on this earth (for oneself, for one’s conscience), and with it the choice of laughter, good spirits, without donning the gloomy mask of the offstage actor. Greetings, old man. As you see, the physical and the moral are naturally good; I shake my brother’s hand.”16

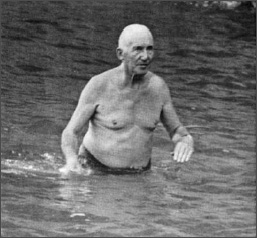

A YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHER took some shots of the seventy-seven-year-old architect walking into the sea in his black swim trunks. Le Corbusier turned to the man with his camera and said, “Don’t take the trouble with an ugly old man like me. It would be better for you to take pictures of Princess Grace, just behind that rock, or Brigitte Bardot at Saint Tropez.”17

8

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret wrote one last time to the companion with whom he had braved winter winds on Alpine peaks when they were both under the age of ten and had their mother and father at their sides. On August 24, responding to his brother’s concern about him, he assured Albert that the Rebutatos were being attentive to his need for a healthy diet and for ample rest and relaxation. “They treat me as if I were a stick of barley-sugar.” Le Corbusier told Albert, “I’ve never felt better.” He chided his older sibling for having taken on the role of nurse. “I’m feeling fine!” he insisted.18

In the Mediterranean on August 25, 1965

Meanwhile, Le Corbusier was correcting the manuscript of Jean Petit’s book about him—in truth, his own book about himself. He praised its preface for saying “that I’m a simple guy. Which is the truth.”19 He probably did not know that this was the same adjective Josephine Baker had used to describe him more than thirty-five years earlier.

Concluding that letter, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret did something rare in his life. He turned his attention completely to the other person. This was not a time to say anything about himself—his beliefs, his achievements. Rather, it was an occasion only to bolster spirits and encourage confidence.

He focused not on art but on music: the passion of their mother, the lifeblood of the household. “Dear old man, go on with your sharps and flats for the delight of our ears. Your music’s in fine shape. You’re eighty and I’m78…. Greetings, older brother.”20

It was one of his distortions for the sake of poetry. Three days later, more than a month before Le Corbusier would have reached his seventy-eighth birthday, his body was brought in by the tide under a lustrous sun.

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

—WALLACE STEVENS, “Sunday Morning”