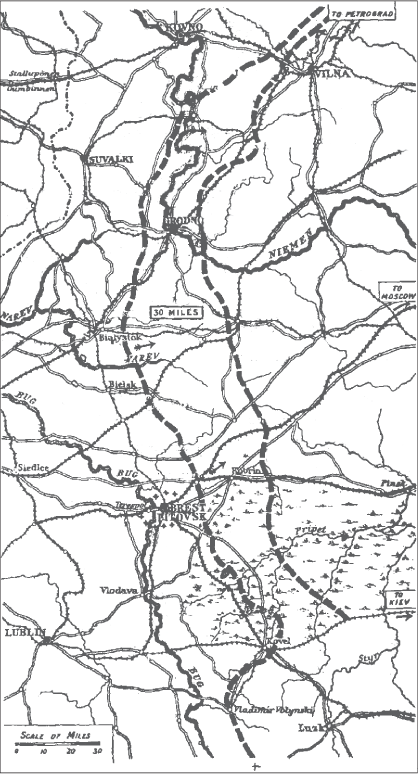

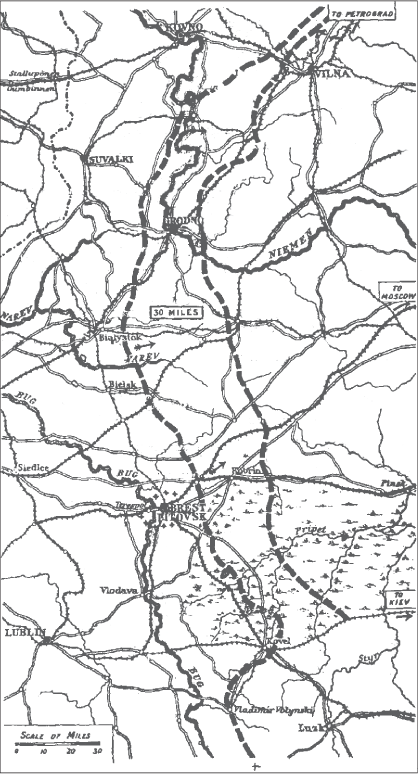

The great retreat after Kovno – a contemporary map with anglicised place names.

Russia’s frontiers were dotted with strategically sited fortress cities, but this was an outdated concept that immobilised artillery which could have been better employed elsewhere. Despite the best efforts of War Minister Vladimir Sukhomlinov, the inertia of senior officers prevented him from freeing much of this artillery from its static role in the fortresses. In 1915 his thinking was proven right, as Warsaw, Przemyśl, Grodno and even Brest-Litovsk either surrendered or were abandoned to the enemy, with the loss of most of their guns and millions of rounds of ammunition of all calibres.89

On the Russian northern front, the fortress-city of Kovno90 was supposed to block any German advance through the Baltic provinces. Its commander, 70-year-old General Vladimir Grigoriev, commanded 90,000 officers and men in a complex of walled citadel and outlying forts with interlocking fields of fire spread out at a radius of eight miles from the city centre. Grigoriev was a prime example of the appointment of Russian officers on grounds of birth and not military competence. On the morning of 15 August 1915 German forces took the south-western outworks. That night, they stormed the forts in this sector, but were driven back. Russian reinforcements began to arrive and were immediately sent into action but, once the outworks were abandoned, the concentrated fire of the enemy’s artillery proved too much for the nerves of the half-trained and badly led defenders.

On 16 August the Germans captured the major fort in the south-western sector, and broke through between two other forts, attacking them from their unprotected rear. In the confusion, some of the forts fired on their neighbours under attack, aiding the Germans.91 At the very beginning of the attack, Grigoriev had created a panic by telling officers who had no intention of running away that the first man to bolt would be shot. Yet, on 17 August, accompanied only by a priest, he left by car for Vilna without telling his chief of staff, so no one knew for some hours that he had gone. By 18 August it was all over, the last defenders literally running or galloping away, to save their lives. A survivor whom Colonel Knox met afterwards informed him that Kovno, although fortified at a cost of millions of dollars in today’s money and having many guns and adequate supply of shells, was simply not constructed to resist modern artillery because the only concrete bunker was Grigoriev’s personal quarters.

In the headlong flight of the garrison, stores had not been destroyed, permitting the Germans to capture not only 1,300 guns, 53,000 rounds of large shell and 800,000 rounds of light shell, but also millions of cans of preserved meat, which provisioned their operations for the following month. Grigoriev was placed under arrest by Grand Duke Nikolai, court-martialled and sentenced to eight years in prison. Among his many shortcomings was the failure to order the demolition of the railway tunnel east of Kovno, which greatly facilitated General Ludendorff’s drive to capture the Baltic ports.92

Just when one would think things at the top could not get worse, they did. On 23 August the Tsar sent Grand Duke Nikolai off to command the Caucasus front, appointing himself C-in-C of all the Russian armies. Some said the grand duke had been sacked because the monk Rasputin persuaded the Tsarina, who in turn persuaded her husband to get rid of his uncle. It was a fatal error. Nicholas’ idea of raising morale was to visit troops and confine himself to frigidly holding aloft a holy icon, before which the soldiers knelt to receive his blessing, while being asperged with holy water by a priest before advancing to their deaths. The generals at Stavka were appalled because the Tsar was extremely indecisive and ignorant of, and totally uninterested in, all things military. As C-in-C, his ‘management style’ was to sit in on the planning meetings of Stavka, but leave without saying a word for or against what was being discussed, leaving only confusion in the minds of the generals as to what he wanted or did not want done.

The great retreat after Kovno – a contemporary map with anglicised place names.

By the end of 1915, the Russian lines had been shortened by the loss of the Warsaw salient, making re-supply easier, and the German and Austrian high commands were hesitant to advance too far into the Russian winter, which had been Napoleon’s mistake and would be Hitler’s. At that point, combat deaths of Russian infantry officers had reduced their number to between 12 and 20 per cent of nominal strength and deaths of other ranks were even higher. Knox calculated that the shortfall in manpower was almost irrelevant because, even had trained replacements been available, there were no fresh weapons with which to arm them.

When the Germans on the Western Front began their massive attack on Verdun in February 1916 the French high command requested Stavka to attack again the German positions in East Prussia to prevent troops being moved from there to Verdun. In the area of Lake Narotch93 the German line was held by General Hermann von Eichhorn’s 75,000-strong 10th Army facing two Russian armies totalling 350,000 men commanded by Gen Alexei Kuropatkin. His appalling performance in the war with Japan when, as C-in-C Far East, he had been unable to control Samsonov and von Rennenkampf, had decided Grand Duke Nikolai to refuse him any appointment, but Nicholas II overruled that decision when he replaced his uncle. On 17 March, Kuropatkin’s 2nd Army launched its attack to relieve Verdun after two days of ineffective shelling that did little damage on the German side, with the result that the advancing Russian infantry were mown down by well-sited machine guns. The 100,000 Russian casualties included 10,000 men who died of exposure in open trenches. Further south, after one Austrian retreat, Florence Farmborough wrote in her diary:

One of our transport bosses offered to drive us over to see the deserted Austrian dugouts. One excelled all others in luxury and cosiness. We decided it must have belonged to an artillery officer. It contained tables, chairs, pictures on the armoured walls and books; there was even an English grammar. We toured some of the smaller trenches. These too were amazingly well constructed. I thought of the shallow ditches with which our soldiers had to be content. Even their most comfortable dugouts were but hovels compared with these.94

Britain’s senior general of the Second World War Sir Bernard Montgomery approved only one Russian general in the tsarist forces. This was Alexei Brusilov, who minimised casualties by making his men dig in properly and undergo specific training for each attack, with full-scale models of the objective. He brought in foreign artillery experts to make his barrages more effective, used cover when available instead of marching men openly across no man’s land, where they were mown down in their thousands by machine guns, mortars and artillery. He also employed deception and might have driven his southwestern front forces through the Carpathians all the way to Budapest, had not the army commanders on his flanks refused to support him.95

The gorodskaya duma – town council – of the Siberian city of Omsk has preserved a fascinating archive of locally conscripted soldiers’ letters home from the fronts 2,000 miles away.96 Many are addressed to the Duma, thanking it for a parcel of what were called in the West ‘soldiers’ comforts’: soap, underpants and vests, tobacco and cigarette paper, needles and thread, writing paper on which the literate could write home. Spoons were another item ‘without which one can starve here’ as one soldier wrote. Pre-printed cards for the illiterate contained the lines ‘I am well/wounded. I hope you are well. Please send me …’ followed by a long wish list.

The preserved letters also describe the war as seen from the common soldier’s viewpoint. On 14 December 1914, machine-gunner S. Gordienko wrote to his family in Omsk: ‘Intensive battle. We were sent into action ten times and could not even get a smoke for several days.’ Early in 1915 another man asked the Omsk Duma to send to his field postal address: ‘a 14-row button accordion because it is spring here and all nature rejoices and we wish to cheer our souls also’. Sentiments were simply, often frigidly, expressed, perhaps because dictated to a literate comrade, like this: ‘Hallo, dear wife, receive my Easter greetings. This is to tell you that I received the parcel you sent last December.’ On 28 March 1915 rifleman Mikhail Nikiforov wrote: ‘Thank you, dear father, mother, brothers and sisters for your valuable gifts. We wish you good health and long life.’ Pyotr Dopgayev of 43rd Siberian Infantry Regiment wrote back to the Duma in Omsk during Easter 1915: ‘Thank you for the parcel with shirts and cigarettes. We have been at the front for nine months.’ A comrade added: ‘We are willing to spend our lives for the Motherland and the Tsar but we do not forget you at home.’ Viktor Zhanzharov wrote on 29 March 1915: ‘Received your gifts. Thank you for not forgetting us. We have now pushed the enemy back [roughly 100 miles].’ Literate soldiers wrote at greater length, as in this exchange:

Hallo, dear comrade Fedya!

I write in reply to yours of 14 January. Has Misha been killed? I was in a battle where bullets cut down my comrades, in front, behind, to right and left. The ranks of my friends and comrades are continually thinning, until there comes that second when a bullet or piece of shrapnel ... Samin has been wounded by shrapnel in the leg and is in hospital in Petrograd. I do not know if he has broken a bone. In battle, bullets punctured my mess-tin and my kit-bag. I had taken cover with kit-bag and mess-tin on my back. My spine is okay but I was wounded in two places. Our old commander was killed at Soldau.97

The reply, written on 25 February 1915 from the northern front was:

Hallo, friend of Fedya!

Best wishes for Easter. I wish all of you can spend this holiday in good health, but must inform you that I have been wounded in a battle between Przasnysz and Mlave. In seven battles I was okay, but had to pay the price in the eighth. From 1 February to 18 February we were in action all the time. The big battle was on 2 February, when we lost 90 out of 240 men. On 11 February we attacked a village and gave the Germans hell, but I was wounded by grenade fragments in right side of body – ear, temple, cheek, upper lip, shoulder and bones of middle finger on right hand broken. Small splinters the size of a pinhead got in left eyebrow and right eyelid. If you are writing home at Easter, pass on the news of what has happened to me. I am temporarily in hospital at Vitebsk.97

Another soldier wrote to his younger brother at home:

Dear Shura,

I asked you to send tobacco and cigarette papers. It would be nice if you enclosed some Siberian canned goods also. Maybe I am not going to come back alive, but all is in the hands of God. I am living in a tent in the forest with combat all around against Germans and Austrians. Many prisoners. There are no civilians here because the Austrians took them as forced labour. We had an air raid the other day – thirty-two aircraft. Above our heads now is an aerial battle. Our planes are being attacked by five Austrian bandits. The other day one of their planes killed several of our horses and one man. So far I am in good health.98

How long Shura’s brother stayed healthy, we do not know. A new menace was threatening the Tsar’s armies. On one day in June 1915 the Germans introduced a new weapon into the war in the east when 13,000 cylinders of chlorine gas were released against the Russian lines, killing thousands of men whose gas masks were stored hundreds of miles away in Warsaw and never were distributed to combat troops. Perhaps it was fortunate that the common soldiers had no idea that Brusilov’s worst problem was not logistics, nor even the enemy forces ranged against him but his fellow commanders, as recorded in his memoirs:

By noon on 10 June 1916 we had taken [Brusilov lists prisoners, weapons captured and booty]. At this stage I was called to the telephone for a somewhat unpleasant conversation with [Stavka] to the effect that [neighbouring Gen] Evert would not attack on 14 June [as agreed in support of Brusilov’s advance] because of bad weather, which made the ground too soft, but would postpone his advance until 18 June. If ordered to attack, he would do so, but without any chance of success. He had requested the Tsar’s permission to change the focus of this attack and the Tsar had given his consent.

I told [General Mikhail V.] Alexeyev [the senior general at Stavka] that this was exactly what I had feared. Even an unsuccessful attack on the other fronts would immobilise enemy forces that could be used against me, whereas the failure of [generals] Evert and Kuropatkin to attack at all left the enemy free to move forces from their sectors. I therefore requested that the Tsar review his decision. Alekseyev replied that it was not possible to question a decision of the Tsar, but Stavka would send me two additional army corps as compensation. I said that moving two corps with all their logistics and support on our inadequate railways would give the enemy, on his far more efficient rail system, time to move not two, but ten, corps against me. I knew very well that the Tsar was neither here nor there in this matter, since he understood little of military affairs, but rather that Alekseyev, who had been subordinate to Kuropatkin and Evert in the Russo-Japanese war, knew exactly what was going on, and was covering up for them.

General Alexandr Ragoza, who had been my subordinate in both peacetime and war, told me afterwards that he had personally gone to Evert at this time to inform him that his attack was well prepared, had sufficient resources to succeed, and that delay would affect his men’s morale adversely. He requested permission to make a report to this effect for forwarding to the Tsar. Evert at first agreed, then refused to forward the report. Ragoza believed that Evert’s motive for repeatedly postponing his attack was jealousy of the success of my offensive and fear of being shown up by me.99

In the Carpathians, combat was complicated by having men from the same ethnicities on both sides. The diary of an unnamed Austrian lieutenant had the following entry for 17 November:

Sergeant Corusa reported some thirty Russians in front of our line, who called out, in German and Hungarian, ‘Cease fire!’ At this double command, fifty of our men left their shelter behind the trees. The Russians opened rapid fire on our poor simpletons and then bolted. Hardly fifteen men came back untouched. Poor Michaelis, the bookseller, hit in the left shoulder by a bullet which came out the other side, was killed and buried there. A Romanian stretcher-bearer laid him on straw at the bottom of a trench and recited a paternoster over him. Two of the other officers had been seriously wounded, so I was the only one left, out of all those who had left Fagaras [modern Făgăraş in Romania] with the battalion.

In the afternoon I took fifty men to hold a slope covered with juniper trees. The men hastily dug trenches, and I made a shelter of boughs. There was no question of lighting fires, so when it snowed once more, everything was wrapped in a mantle of snow. In the evening, when I went to inspect the men lying in their coffin-shaped scrapes covered with juniper branches, they looked to me as if they had been buried alive. Those poor Romanians!100

The diary entry for 20 November describes officers and men delousing themselves:

Issued with winter underclothes and defying the cold, the men lost no time in undressing to change their linen. I saw human bodies which were nothing but one great sore from the neck to the waist. They were absolutely eaten up with lice. For the first time I really understood the popular curse, ‘May the lice eat you!’

One of the men, when he pulled off his shirt, tore away crusts of dried blood, and the vermin were swarming in filthy layers in the garment. The poor peasant had grown thin on this, with projecting jaw and sunken eyes.101

The point of including here the excerpt from the Austrian lieutenant’s diary is that conditions were at least as bad for the men in Russian uniform they were trying to kill, or were being killed by. Visibility was so reduced in the Carpathian Mountains by juniper bushes growing thickly everywhere that the lieutenant’s detachment had to fire blind through the undergrowth whenever they heard what appeared to be enemy movement. When the lieutenant went to reconnoitre one suspected enemy position, he narrowly missed being shot by a 300-strong battalion of his own infantry. Although the enemy was only thirty paces distant, the undergrowth was so thick that nothing could be seen of them. He wrote:

Private Torna came to our shelter to announce, ‘Sir, the Russians are breaking through our line on the top of the hill!’ I asked my friend Lt Fothi to take command in the trenches, pulled on my boots, took my rifle, and ran to the edge of the woods. I could hardly believe my eyes. Along the whole company front, men in Russian uniform and some of our men were threatening each other with fixed bayonets and, in places, firing at each other. In one place, some Russians [sic] and some of our men were wrestling on the ground to get at a supply of bread intended for 12th Company. This struggle of starving animals for food only lasted a few seconds until they stood up, each man having at least a fragment of bread, which he devoured voraciously. This is how bread reconciles men even on the field of battle, when they make peace to get a scrap of bread.102

An hour later, a group of men in Russian uniform appeared 200 paces away on the edge of the woods with rifles shouldered, beckoning the lieutenant’s men to approach. A squad of twenty men under a sergeant major was ordered to surround the Russians with fixed bayonets and bring them in. The Austrian lieutenant’s diary continues:

I clambered over the body of a man whose brains were sticking out of his head, and signed to them to surrender, but they still called to us without attempting to move. I thereupon gave the order, ‘Fire!’ and held my own rifle at the ready. At this point my Romanians refused to fire, and, what was more, prevented me from firing also. One of them put his hand on my rifle and said, ‘Don’t fire, sir. If we fire, they will fire too. And why should Romanians kill Romanians?’ He meant that those men were from Russian Bessarabia [and spoke a dialect of Romanian].

I tried to make my way towards them but two of my men barred my way, exclaiming, ‘Don’t go and get yourself shot!’ It was incredible. Our men were advancing towards the enemy with their arms shouldered, and were shaking their hands. It was a touching sight. I saw one of my Romanians kiss a man in Russian uniform and lead him back to our lines. Their arms were round each other’s necks, like brothers. It turned out they had been shepherd boys together in Bessarabia. We took ninety Russians [sic] as prisoners in this way; whilst they took thirty of our men off with them.103

That inconclusive day was considered a victory because the company had prevented the Russian troops from outflanking their positions. So men who had distinguished themselves all received the second-class medal for valour. Three officers, including the writer of the diary were also awarded the Signum Laudis bar. After that, they marched through thick forest to divisional HQ at Hocra, the winter conditions making it a different hell. By the time they arrived late at night, company strength had dwindled to a quarter of what it had been at the start of the march. Even some of the veterans dropped out, weeping from exhaustion, and were abandoned en route. It was, as the lieutenant said, by the mercy of God if they survived the freezing night and the wolves in the forest.

The company was dissolved after having been reduced to the strength of a platoon. On 27 November the survivors left Havaj early, but marching was difficult, for the men were worn out and the lieutenant admitted to being ‘nothing but a shadow’. During one halt, Austrian bureaucracy caught up with these exhausted men, who were required to make a full return of all missing kit. This was a nonsense for men whose uniforms were in rags, and filthy, with lice swarming all over them. Most of them were fighting in the snow-covered forest without boots, and had wrapped rags around their tattered socks to avoid losing their feet to frostbite.

At midday the lieutenant and his men set off again up a forested hill badly cratered by Russian artillery, with shells of all calibres falling thick and fast and machine gun bullets penetrating the undergrowth from hidden positions. At the top of the hill, the unit came under the orders of a colonel, who ordered several men to take a house about 1,000m behind the Russian front line, saying that they would be shot if they returned, having failed in the mission. They realised that he had gone mad, but the men obeyed and few returned.

Throughout that winter, the senseless killing ground on and on. Men on sentry duty had to be relieved every two hours on account of the bitter cold. By the end of November, of all the officers in the battalion only the sub-lieutenant and the surgeon were left; of the 3,500 men on the original roll call a mere 170 remained. Of the sub-lieutenant’s company, which had been 267 strong, only 6 now survived. A bag of bones shaking with fever, he was given permission for convalescent leave, said farewell to his last few men and had to walk for two whole days to reach a town, from where he was driven to the railhead and caught the last train to Budapest. He ends his diary, ‘God had willed that I should return alive.’104

Even when they did eventually get word, ‘news from home’ was unlikely to motivate the average Russian conscript. The seeds of rebellion were already germinating as the New Year of 1917 dawned. Lenin was still in Switzerland and Trotsky was held in a POW camp at Amherst in Nova Scotia, where he was making a nuisance of himself with the other prisoners and the personnel, after being forcibly removed from the Norwegian ship Kristianiafjord bringing him back to Europe from New York, where he and his family had been living on 164th Street in a walk-up apartment costing $18 per month. He was still in the camp, on the wrong side of the Atlantic, when soldiers sent to restore order in Petrograd joined forces with the rioters in the streets and occupied the Duma building on 26 February 1917. Throughout the vast Russian Empire, just about every commodity was either in short supply or impossible to obtain; even basic food had to be queued for. Hundreds of thousands of homeless refugees from territories captured by the Central Powers added to the strain on the system. Inflation mounted; wages did not. The troops’ dissatisfaction with the many obviously incompetent generals led to massive desertion and open mutinies at the front. At home, strikes – particularly in the war industries – became increasingly disruptive.

The Duma warned Nicholas II that society was collapsing and advised him swiftly to form a constitutional government, as was done on paper after the 1905 revolution, but Nicholas had recently discovered dominoes and was currently devoting more time to mastering the intricacies of the various games one can play with them than to the war or affairs of state. The Tsarina Alexandra was in deep mourning for Rasputin, who had been assassinated rather messily in December by a cabal of nobles, determined to rid the court of his defeatist influence on the German-born Tsarina. In between visits to his tomb, constructed at her command in the royal village of Tsarskoye Selo, she blamed the social unrest on the rabble in the streets and the politicians in the Duma, advising her husband by letter that the workers would go obediently back into the factories, if he threatened to send every striker to the front. With desertion from the Russian fronts running at the rate of 30,000-plus every month, or 333,000 men in one year, this was hardly useful advice.

As to the lives of the predominantly peasant population of eastern Poland and the Bukovina, fought over for the second or third time in this war with all the men of military age conscripted by one side or the other, the suffering of the women, children and the elderly defies even imagination. Successful Brusilov’s 1916 offensive undoubtedly was in military terms, but with Russian losses in the war so far amounting to 5.2 million dead, wounded and captured, even the long-suffering subjects of Tsar Nicholas II were aghast at the scale of fatalities. Bereaved families from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean and from the White Sea to the Caucasus mourned the loss of fathers, sons, brothers, uncles and cousins.

Despite all its other concerns, the provisional government allowed the Petrograd Soviet to bully it into protesting to the British government at the detention of Trotsky in Canada because of his many speeches and writings against the war effort, with the result that he was taken out of the camp, reunited with his wife Natalya and their sons – all the family being put aboard the SS Helig Olaf to continue the journey to Russia. As the ship pulled out of the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Trotsky was seen shaking his fists at British officers on the dockside and cursing England, which he blamed for making him late for the revolution. Having no further trouble while travelling through Sweden and Finland, he eventually arrived on 4 May – one month after Lenin’s return – at Petrograd’s Finland station, to be given a hero’s welcome from revolutionary socialists of several hues, impressed by his history of heading the Petrograd Soviet during the 1905 revolution, his prison sentences, periods of internal exile and his record of relentless writing and speaking during the years of exile in Western Europe. Only the Bolsheviks regarded his return warily, perhaps with the exception of Lev Kamenev, married to Trotsky’s sister Olga. A less arrogant personality would have felt his political way cautiously after being away so long but, as historian Robert Service commented, Trotsky was ‘thirty-eight years old and brimmed with energy and self-belief. He felt he was coming back to fulfil his destiny.’105 He also had the advantage of the long absence allowing him to step down from the train at the Finland Station and voice the same ideas he had promoted twelve years before – many of which had meantime become Bolshevik Central Committee policy. While he and Natalya threw themselves into the daily hurly-burly of revolutionary debate, at which Trotsky was a master, their sons Lëva and Sergei were welcomed by Trotsky’s first wife Alexandra and her two daughters by their common father and spent the summer at the Finnish seaside resort of Terijoki, just like the sons of any bourgeois family from Petrograd, so their parents were not short of cash.

In the late spring of 1917 Florence Farmbrough’s letuchka was posted to north-eastern Romania, where the villagers – all of whom kept some chickens – refused to sell them eggs. When they complained of this to a French-speaking Romanian officer, he told them politely enough that his own people had not enough food for themselves. So, the nurses were reduced to living on kukuruza – a gruel made from maize usually fed to ducks and chickens. Although Jews would rent them accommodation, the Romanian peasants refused to, on the grounds that Russian soldiers had regularly looted private property at gunpoint and had also broken into official food stores when their own supplies failed to arrive.

Managing to set up a dressing-station nevertheless, the nurses found two Russian female soldiers among their first batch of wounded. They belonged to the Women’s Death Batallion, formed and commanded by an amazing woman called Maria Bochkaryova. After leaving two wife-beating husbands, she had been given the Tsar’s personal permission to enlist in 25th Tomsk Reserve Battalion, where she defied abuse and harassment by her male comrades, fighting alongside her third husband until he was killed in Galicia. Appalled by the number of soldiers deserting on all the fronts, she had returned to Moscow with her slogan ‘If the men will not fight for Russia, we women will’. Her original 2,000 volunteers were whittled down by harassment from their male comrades and also by the ferocious discipline Bochkaryova imposed. Finally, their numbers dwindled to a hard core of less than 300 fighting on the Galician and Romanian fronts. Both the women soldiers being treated for wounds by Letuchka No. 2 were, Florence noted, too shocked to say very much about their experiences in combat, but the driver of their ambulance cart said that the Women’s Death Battalion had been ‘very cut up’ by the enemy. Nor were they the only women in combat in Romania, where some local women were fighting alongside their menfolk in the region of Ilişişti. Their wounded were also treated by the letuchka nurses.

The poverty of the Romanian peasants was epitomised when Florence, a keen photographer in her spare time, wanted to take the picture of a woman in traditional dress, who agreed to pose for her providing the family’s most precious possessions – her husband’s boots – could be prominent in the shot. The nurses’ patients were not only adults of both sexes, but also young children, usually the victims of shrapnel bursts. Increasing numbers of unkempt and filthy Turkish prisoners of war were also brought in and cleaned up. Their wounds were dressed and they were given clean shirts and trousers. Even when the wounded being treated at the letuchka were deserters with obviously self-inflicted wounds, the nurses caring for them increasingly came in for verbal abuse from Russian mutineers, who were stirring up trouble among the Romanian soldiers. What she described as ‘strange-looking men’, some in uniform and some in civilian clothes, harangued large numbers of angry soldiers at unofficial meetings, making revolutionary speeches and urging them to desert in order to save their own lives. The revolution had caught up with the war.

At Stavka, Knox was told that the shortage of rifles and compatible ammunition was due to losses of weapons with men who had been taken prisoner, plus those wounded and killed during retreats. Yet, on several occasions he had seen perfectly serviceable rifles lying on battlefields three and four days after the fighting, with no attempt made to recover them. Other shortages included 500,000 missing pairs of boots, sorely needed by men in snow- or water-filled trenches during harsh winter weather. As early as December 1914 there had been instances of men shooting themselves in the leg or foot, who were helped back to the rear by an unnecessarily high number of ‘carers’. Knox observed that when an Austrian attack was coming in, the local Polish peasants sat tight, but when the advancing troops were German, they fled eastwards towards Russia. What roads there were, were blocked with long columns of farm carts transporting families with all their moveable possessions. Old people, women and children huddled on top of their pitiful bundles, hungry and shivering in the cold and rain.