Whether walking in the yard, sitting in their rooms, or working their shifts, the tunnelers continually hashed out how, once through the sap, they would make it across the 150 miles to the border. In fact, the distance they would have to travel as fugitives would be far greater given the detours needed to avoid towns and major roads. Gray was particularly aware that most escapes fell apart in this phase. Day and night, he considered different plans, searching for something foolproof.

Most of the tunnelers were banding up in teams for the flight to Holland, and Gray was committed to going with Blain and Kennard. He would not do a solitary run again; his own from Crefeld had proved to him how important it was to have partners who would look out for one another. There were few braver, tough, and more cool-headed when it mattered than Blain and Kennard. Travel by train Gray discounted, chiefly because a mass breakout would result in Niemeyer dispatching police to every nearby station and alerting conductors to confront any suspicious passengers. This left a journey by foot. Moving at night and hiding out during the day limited their chances of discovery, but Gray also knew that there was almost no way to cover such a distance without being spotted and forced into some kind of interaction. They would need disguises and cover stories.

A helpful pamphlet on whom to avoid when escaping a German prison camp.

Gray spoke German fluently, but Blain and Kennard would have far more trouble. Blain had Cape Dutch from his time in South Africa and could make an attempt at answering some simple questions, but Kennard was unable to manage more than a few prepared phrases. Knowing this, Gray considered a plan where he would act as an officer escorting a pair of privates. Given his rank, he would be expected to answer for them. However, if challenged to any degree by a higher official, Blain and Kennard might be required to speak, and then they would be in trouble. Further, their uniforms would never remain sufficiently clean to pass for military inspection after they had tramped through woods and slept out of doors. No, Gray decided, they needed a plan that was sure to convince any doubters. Something extraordinary.

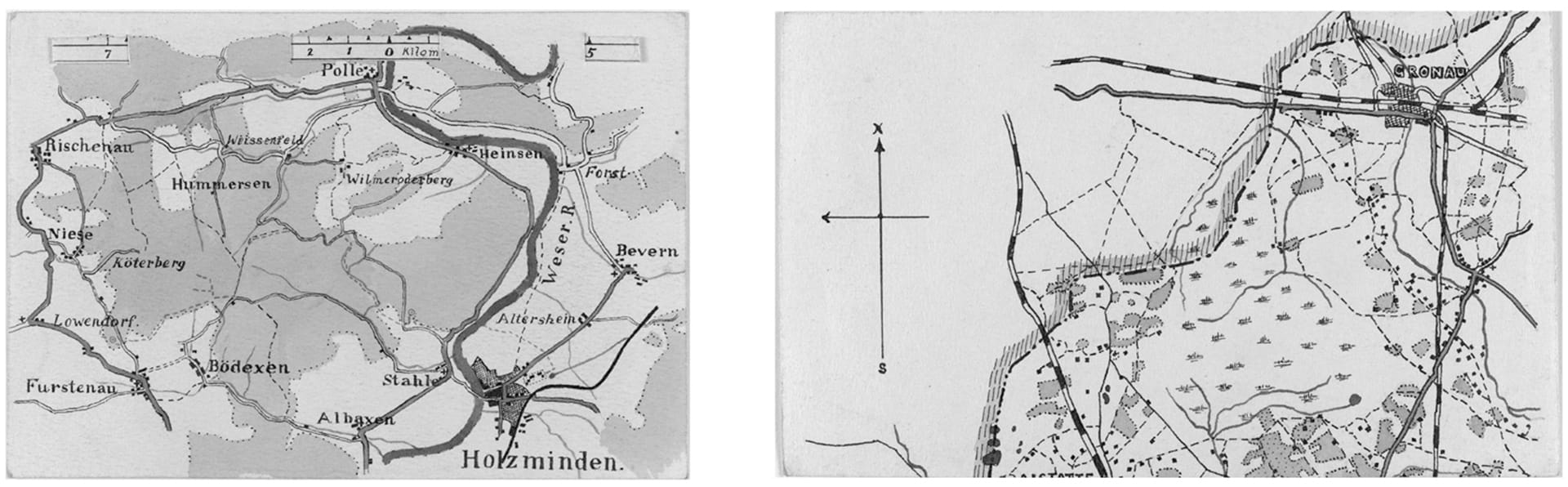

There was a lot to do in preparation. They needed good maps and compasses as well as food for 15 days of travel and Tommy cookers to heat their meals. They needed warm clothes and tough boots. They needed waterproof sacks to get their belongings across the river Weser. There were documents to forge, clothes to tailor, photographs to take. In the unoccupied Room 83, the tunnelers assembled a veritable escape factory—or, as they called it, “a temple to the Goddess of Flight.” They hid items under floorboards and behind sliding paneled walls, along with all manner of equipment used in their preparations, including locksmithing and woodworking tools, a sewing machine, and dyes, inks, and paper for passes. They had built their tunnel bellows in this room. By mid-April they were hard at work making passes and creating backpacks from old jackets smeared with lard.

In all these efforts, they had help. Since first arriving at Holzminden, officers had bribed and inveigled some of the guards and other staff, turning them into willing accomplices who provided information or special items. Niemeyer’s poor treatment of his men made them easy turncoats. As one British officer described, when the commandant tired of abusing his prisoners, he vented his “black gusts of bilious passion” on his staff, often leaving them “literally trembling as he flayed them with his tongue.” The war’s harsh economic rationing was added motivation.

Moccasins made by Holzminden POW Edward Leggatt for his escape.

A compass used by Leggatt during his escape attempt.

Leggatt’s escape maps.

“Letter Boy,” the commandant’s clerk, was easily charmed with coffee and cookies. His work delivering letters gave him free rein to move about the barracks, and he met almost daily with the conspirators to pass along the latest intelligence or material he purchased on their behalf. What was more, he always knew when searches were coming and where they would occur. The “Sanitary Man” was the only civilian at Holzminden who could go about without a guard accompanying him. In exchange for some cash and something from Fortnum & Mason—the upmarket London grocery store—he would shop in town for any goods the prisoners requested. “The Typist,” a young secretary in the Kommandantur, helped them for less mercenary reasons. She had fallen in love with Peter Lyon, a 6-foot-3 Australian infantry officer who was a member of the tunnel conspiracy. Since his capture in spring 1917, Lyon had lost over 60 pounds because of an insufficient diet, but none of his good looks. Between exchanging love notes, the Typist provided sample passes and the paper stock on which they were printed. Finally, there was Kurt Grau, a well-meaning camp interpreter. He had been stationed in India and once proclaimed, “I do not care for Germany. I do not care for England. My heart is in India.” As Gray had served a number of years in the army there, not to mention it being his birthplace, he was able to convince Grau that he could help set him up in India when the war was over. Grau became a friend to their cause.

The tunnelers benefited as well from their continued alliance with several orderlies. Beyond providing access to their quarters, these men also helped with the escape factory. With his photography experience, Dick Cash was foremost among them. Not only did the officers need photographs for their passes, they each needed a copy of a map for their journey. It was one thing to chart a general westward course and quite another to have a map to identify every village, road, waterway, and town they came across. The ability to do so might separate success from recapture. They had managed to smuggle into Holzminden a large military map that covered the expanse of territory they would cross. Cash made a shopping list: camera, plates, chemicals, printer paper, and a carbide bike lamp to develop the film. He started collecting what he needed. Each week, Gray asked for additional copies of the map, because as the sap lengthened the number of officers brought into the fold increased.

Protocol required that Lieutenant Colonel Rathborne, as senior British officer after Wyndham had been sent to another camp, be informed of the plan. What was more, he could use his position to stall other attempts that might result in their tunnel’s discovery. Gray also knew that Rathborne was keen to escape himself. When notified, Rathborne not only gave his blessing but volunteered to join the scheme and to help in any way he could. Others were brought in to stand lookout as well as to obtain boards to brace the tunnel walls, sacks to pack dirt into, and tins to extend the ventilation pipe. With each additional member, the chance of exposure grew, but Gray accepted the risk. There was no other way to build a tunnel of that length and to orchestrate a well-prepared, properly supplied home run to Holland.

One afternoon, Gray finally struck upon an idea for his own escape run with Blain and Kennard. He was in the tunnel chamber with the two of them, and they were getting ready to start their shift. Kennard lit a candle and knelt down by the sap entrance. Looking into the dark hole, he muttered, “We must be bloody mad.”

“That’s it!” Gray exclaimed. Blain and Kennard looked at their usually taciturn friend as if he had suddenly lost the run of himself. “Mad!” Gray chuckled. “Mad! That’s the answer. It simply couldn’t miss!” The other two tried to get him to explain, but he told them that he wanted to think on it some more, to investigate its faults and merits. “Come on, let’s get on with it,” he said, taking the candle from Kennard. “I think I’ve come up with the answer to our prayers, that’s all.” With that, he crawled into the tunnel, the first digger of the day.

Then a run of bad luck and imprudence put everything in jeopardy.

First, rumors of the scheme began to filter throughout the camp. With roughly two dozen individuals in the know as well as the strange movements of officers in and out of their quarters, keeping their activities secret was impossible. But it was one thing to hear a rumor and quite another to know exactly where the tunnel was located. An orderly known to spy for Niemeyer in exchange for gifts of wine began asking around camp about where the tunnel’s entrance was hidden. It was too great a risk for the tunnelers, and one night, while drunk, the orderly “accidentally” tumbled down the steps in Block B and cracked his skull. He never made another inquiry.

In mid-May, Niemeyer instituted reprisals in response to restrictions put in place against German officers in Britain. Worst of these, for the tunnelers, was a new schedule of roll calls. Instead of twice a day at 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., the prisoners were now forced to gather on the Spielplatz at 9 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 3:30 p.m., and 6 p.m. These frequent roll calls cut straight into the middle of the four-hour tunnel shifts. At first the tunnelers tried standing in for those on shift. When the names of the working crew were called, their mates answered for them, then moved down the line to respond to their own names. They pulled it off for a few days but were sure that continuing the charade day after day would see them caught.

They began to rush to and from their digging sessions between the 11:30 and 3:30 roll calls, the time of the day when most guards were away from Block B for lunch. Roll calls took at least a half hour, which meant that, even hurrying, the teams of three had less than two hours underground. Their recklessness quickly cost them. One day, after finishing a shift, a working party was hurrying out of the east door of Block B without taking the usual precautions, and one of the officers was recognized by a passing guard. The guard tried to stop the officer, but he rushed away into the barracks through his own entrance.

Niemeyer was informed of the incident, and a search of Block B followed, but the guard could not identify the officer in question. All the prisoners were ordered onto the Spielplatz, and an exhaustive inspection of the orderlies’ barracks began. The tunnelers waited for the fateful moment when their secret door would be found. After a long time, the prisoners were ordered back into their barracks. Yet again, the door had eluded discovery. The tunnelers breathed easy at last. Upset that nothing had been found, Niemeyer vented his spleen on the guard who had failed to identify the officer, sending him to the jug for eight days. He also posted a permanent guard on the steps outside the orderlies’ door. With this, the tunnelers lost their access point. It was a cruel blow.

They immediately decided to stop all activity. The Germans were on alert, and anything out of the ordinary was sure to raise suspicion. During that time, horrible news reached them via the Poldhu—Harold Medlicott and Joseph Walter had been murdered.

Having escaped from Bad Colberg camp in Saxony, some 150 miles south of Holzminden, they had been caught on the run. The camp commandant, a man called Kröner, had sent eight of his most fearsome men to get them at the local train station. Before leaving, one of them was overheard saying, “Yes, they are two very brave men, but they will be shot.” Later that afternoon, the guards returned to the camp with two stretchers covered in dark sheets—clearly the dead bodies of Medlicott and Walter. According to Kröner, they had been shot in the Pfaffenholz forest after a “sudden dash for freedom” from the station.

The senior British officer at Bad Colberg demanded to see the bodies. If they had been killed in the manner reported, the nature of their wounds would match the story. Kröner refused. Then, while several British officers distracted the guards watching over the bodies, another officer rushed up and threw aside the sheets. Medlicott’s and Walter’s bodies were riddled with over a dozen bullets and stabbed with several bayonet wounds. It was evident that they had been murdered; Kröner’s story was a patent lie.

The tunnelers in Holzminden had little doubt that they risked the same fate if they too were caught escaping. Niemeyer had proven himself time and again to use force—either by bayonet or bullet—to make a statement. But the prisoners were undaunted. They surveyed the barracks and grounds again, looking for another way down to their sap. Nobody lived in the attic of the officer section in Block B, and, as a result, the Germans were unlikely to inspect any of the rooms too closely. The double swing doors onto the floor were secured with a metal chain looped between the steel handles and a heavy padlock. Picking the padlock would be too time-consuming, but the handles themselves were only fastened to the door by six screws. Remove the screws, take off one handle, and they could access the floor. Afterward, replace the screws and handle, and nobody would be any the wiser.

There was a barricade separating their quarters from those of the orderlies, but they found a way to bypass it: the eaves. These ran the length of the barracks like a corridor under the steeply sloped roof. If they cut a panel in the wall in one of the rooms, they could use the eaves to reach the eastern side. This they quickly did, making the opening look seamless with the wall by using some mortar and distemper paint and hiding it behind an unused bed. Then they discovered a small door at the other end of the eaves that opened into an attic room where some of the orderlies slept. No doubt the original builders put it there to access the space. Not only did this solution return access to their tunnel in the cellars, it was a far superior approach. They would no longer need to risk masquerading as orderlies to get past the guards. More important, apart from showing up for roll calls, they could dig day and night.

And so they resumed work, quickly making up for lost time.