2Ordination and Early Education

TAKING UP OFFICIAL RESIDENCE AND BEGINNING MY EDUCATION

IN MY FOURTH YEAR, on the twenty-third day of the first month of the wood-dragon year (1904), I was taken for the first time from my birthplace to Trijang Labrang in Lhasa. That day was the conclusion of the Great Prayer Festival in Lhasa, and following the tradition, the current throneholder accompanied by lay and monk officials had gone in formal procession to perform the customary blessing of Lhasa’s Kyichu River dam. Our party proceeded just after the throneholder’s party had returned from this ceremony, and thus, without having been planned, there was a spontaneous reception as if the throneholder had come out to greet me. This was said at the time to have been an auspicious sign.

Just before we arrived at the entrance to our house, a miller’s daughter carrying a large sack of wheat on her back stopped to look at our procession. The spectacle must have distracted her attention, for the rope that secured the sack slipped from her hands, and all the wheat poured onto the ground, blocking the labrang entryway. Taking this to be another auspicious sign, all who were there to greet me grabbed handfuls of the wheat and threw it at us in welcome. The bursar of our labrang had to later reimburse the miller with another sack of wheat.

Just after we arrived, a formal reception ceremony was held in the main assembly hall. Whether for a special purpose or for some other reason, my throne faced north, and the masters and staff of Ganden, who had come to welcome me, sat in a row at the north side of the hall facing south. Among them was Khedrup, the incumbent treasurer of Shartsé College, who shared the same household with Khamtruk, a man from Chatreng who had been a bodyguard of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and had experienced some difficulties with my predecessor. Although Khedrup sat in the row with the others who were welcoming me, his were not thoughts of welcome. Staring at him I touched my finger to my cheek, indicating that he should be ashamed. Everyone was quite surprised, and naturally he became flushed with guilt.

A few days later, Ngakrampa together with Dzongsur Lekshé Gyatso and some others took me for the first time to Chusang Hermitage. When we arrived there, we were greeted by the master of the hermitage, Dromtö Geshé Rinpoché, a dignified white-haired monk who had both received from and given teachings to Kyabjé Vajradhara Phabongkha Rinpoché. In a formal receiving line there were also several other senior monks attired in their ceremonial robes and hats. A throne had been set up for me facing east in the main prayer hall, and after I was seated on it, tea and rice were served, and the monks performed the long-life ceremony of the sixteen arhats for me. I still remember that among the ritual objects that were handed to me and then taken back as part of the ceremony was a beautiful silk appliqué of a mongoose, which I refused to give back for quite some time.

About ten days later, Ngakrampa had a small wooden board for writing specially made for me. Since the translators of old had propagated the doctrine in Tibet by first studying the Indian texts written on palm leaves, he considered this to be an auspicious way of beginning my education. He printed on my wooden board the thirty letters of the Tibetan alphabet as well as all the subscripts and superscripts. He also wrote a few verses of alliterative children’s poetry. In this way he taught me the alphabet, the building blocks of all literature.

I delighted my teacher by learning all thirty letters that very day. Thereafter, he would boast that his charge had learned the ka kha ga alphabet in a single day. Ngakrampa spent a long time teaching me to read and spell from printed editions of the Buddha’s Eight Thousand Verse Perfection of Wisdom and the Son Teachings from the Book of Kadam.20 He also had me practice on a text that had been written out in longhand with numerous abbreviations: the Stages of the Path by Kachen Namkha Dorjé, who was a direct disciple of Paṇchen Losang Chögyen.21 Because of my teacher’s thoughtful instructions, I was able from then on to read with ease an entire book every day, be it printed or handwritten.

Whenever Dzongsur Lekshé Gyatso would come from Lhasa to Chusang Hermitage, where I was staying, I would say before he arrived, “Mr. Dzong is coming,” and then he would arrive. One day, late in the morning, I suddenly said, “Lhundrup died.” We found out later that an old servant in the Maldro Jarado Labrang, a former monk named Lhundrup, had died just at that time. Ngakrampa thought these occurrences extraordinary, and so he noted them down. Actually, they were just the babbling of a child who says whatever comes to his mind. This situation was not unlike that of the pig-headed fortune teller.22 After all, how could I, someone who is not even sure where he will defecate at night the food he ate in the morning, know of things hidden in the future?

When I had reached the age of five, my father took the vows of a novice and a fully ordained monk from Venerable Khyenrap Yonten Gyatso, who was then the incumbent Jangtsé Chöjé and later became the Ganden Throneholder. My father was given the name of Khyenrap Chöphel. My mother Tsering Drölma, my sister Jampal Chötso, and my younger brother took up residence in the estate that my father had left to them. It was in a place called Gungthang Chökhor Ling, near the residence of an uncle named Gyatso-la, who was a monk at Chötri College of Gungthang Monastery.

When I was six years old, Demo Rinpoché23 of Tengyé Ling Monastery, who was the same age as I, came to visit Mr. Lokhé, his monastery’s bursar then staying at Chusang Hermitage. One day they came to my residence, and I met Demo for the first time. We were so small that we were both put in the same chair. Then for no apparent reason, the two of us began to cry. It seems that, ever since the time of Ganden Throneholder Jangchup Chöphel, our two labrangs had very strong religious and secular connections. Demo’s predecessor had been a regent of Tibet and was imprisoned by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. While in prison he died, and so it seemed to both Ngakrampa and Mr. Lokhé that the two of us were crying in remembrance of the difficulties that Demo’s predecessor had endured. Actually this was just another coincidence, for I had no idea why I was crying.

THE ARRIVAL OF KYABJÉ PHABONGKHA RINPOCHÉ

Later that year, Kyabjé Vajradhara Phabongkha Rinpoché came to Chusang Hermitage. This was as if the force of my prayers combined with a considerable store of accumulated merit had rolled a giant boulder of gold right up to my door. For seven years, until the end of the water-rat year (1912), he lived in the guesthouse on the debating ground of my residence.

At the beginning of this period he was twenty-nine years old and had just left Gyütö Monastery, the upper tantric college.24 For attendants he had only his elder brother Sölpön-la, who later became the senior treasurer known as Ngawang Gyatso, and another aid named Losang, who had been provided by the Shöl Trekhang family.

Once in a while Tsangyang, a geshé from Gyalrong House of Sera Monastery who was a very talented cook, would visit Phabongkha Rinpoché for a few days and at those times would serve as chef. From time to time various masters would gather at Phabongkha Rinpoché’s retreat house and exchange teachings that they had heard. Among them were Gungtrul Rinpoché, whose personal name was Khyenrap Palden Tenpai Nyima, Gangkya Rinpoché of Phenpo, Minyak Rikhü Rinpoché, who was a master from Kham, and Dromtö Geshé Rinpoché, the master of Chusang. Sometimes twenty to thirty monks from Sera and other monastic universities would come for teachings.

Between these periods Phabongkha Rinpoché would usually go into secluded retreat, after which he would perform a fire offering. He himself would make all the preparations for this ritual. He would draw the necessary hearth diagrams, arrange the ritual objects, mix the four libations, and so forth. Because I was so young, I treated these occasions as a playful distraction and would compete with Sölpön-la to assist during the ceremony by trying to hand over or receive back the offering substances before he could get to them.

Apart from an enormous number of books, the precious lama had few possessions, and his living conditions differed little from those of an average monk. After learning my lessons in the morning, I would have a break until lunch and so would go to the debating ground to play. Time and again when I came into the presence of my refuge and protector, I treated him as an equal without any reverence or courtesy, with the attitude of a child. In his presence I would perform imitations of religious dances that I had named Dance of the Lotus and Dance of White Light of Gungthang. Sometimes I would leap into his lap and play. He was a very good artist, and while sitting there he would draw all sorts of things on paper. Occasionally we would have lunch at the same time, and I would share his seat and his plate.

Although I was quite a bother, this precious lama was so very kind and gentle that he cared for me joyfully and lovingly, without ever once becoming upset or irritated. Thinking back, I received many vast and profound teachings in the presence of this incomparably kind master, who was like a father to me, but from the standpoint of practice and accomplishment, I was unable to realize the full intent of his teachings. Thus I hold the pretentious position of a fire placed in the rank of the sun, for I have been like a son who disregarded his father’s last words and threw his will to the wind. Although I have propagated the discourses and esoteric practices of Dharma, principally through teaching the stages of the path, this is a mere reflection, a mimicking of my master’s teachings.

When I think back on my carefree behavior as a thoughtless child, I feel that this led me not astray but rather in a good direction. It is said that devotion to one’s master is the root of every good in this life and the next, and later in my life I had the opportunity of serving to the best of my ability in every way, materially and spiritually, the next incarnation of this supreme master, from the time when he was first recognized until he earned the degree of geshé lharam. I was able to serve in every way except to prevent his untimely death, which was a serious setback to the propagation of the Buddhist doctrine.25

MEMORIZATION OF TEXTS

The first text that my teacher Ngakrampa had me commit to memory was Chanting the Names of Mañjuśrī. After I had memorized it, he required that I recite it every day without fail. He then had me memorize the short texts of worship for the red and yellow aspects of Mañjuśrī and required that I regularly repeat the mantras for increasing wisdom. In the hope of increasing my wisdom still further, I voluntarily recited one of these mantras not only every morning but every evening as well, eventually completing a hundred thousand repetitions.

Once, my elder half-brother Khamlung Rinpoché came from Sera Monastery to visit me at Chusang. He brought as a gift his monastery’s reading primer, as he assumed that I had yet to learn the Tibetan alphabet. It both embarrassed and pleased him to discover that I had already memorized most of Maitreya’s Ornament of Realization together with several different types of ritual texts.

At the age of six it is difficult to do extensive memorization, but Ngakrampa was extremely skillful in the way he raised me, applying discipline and patience in their appropriate places. Although I had no real understanding of what I was memorizing, I would make up my own interpretations, and this made it easy to hold the words in my mind. I would later ask Ngakrampa to explain the meaning of these texts, and since I had already memorized the words, the conditions were then present to support a clear comprehension.

MY ORDINATION AT RADRENG MONASTERY

In the fourth month of the fire-sheep year (1907), at the beginning of my seventh year, I left Chusang Hermitage accompanied by Ngakrampa Losang Tendar, our treasurer Chisur Lekshé Gyatso, and Chatreng Nyitso Trinlé Tenzin of Gashar Dokhang House. Several others, including Nenang Dreshing Geshé and Sölpön Phuntsok, also joined our party. We traversed Phenpo Go Pass and stayed the night at the temple in Langthang. We then went over Chak Pass and traveled via Phödo to Radreng Monastery.26 There, on the eighth day of the fourth month, the fourth reincarnation in the succession of the Radreng masters, the glorious and revered Ngawang Yeshé Tenpai Gyaltsen conferred upon me the precepts and vows of a layman and of a novice monk. He gave me the name Losang Yeshé Tenzin Gyatso and composed an eloquent prayer for my long life, which began with this line: “The Buddha’s exquisite attributes charm the eyes of a wild mountain deer.” I then received the further kindness of his oral transmission of Candrakīrti’s Entering the Middle Way and the Ornament of Realization.

The fifteenth day of that month happened to be a prayer festival at Radreng Monastery. I witnessed the unfurling of their enormous silk pictorial appliqué thangka, ritual dances, and so forth. Then I went to see the monastery’s most sacred image, which was a statue of the Buddha known as Lord Mañjuvajra, visited the smaller chapels, and made one thousand offerings. I also visited religious centers near Radreng, such as Tsenya Hermitage, Yangön Hermitage, and Samten Ling Nunnery, where I paid homage and made offerings.

Previously, while learning to read at Chusang Hermitage, I had read the Son Teachings of the Book of Kadam twice from beginning to end and so had a good recollection of the story of Atiśa’s disciple in his incarnation as King Könchok Bang. Thus when our guide at Radreng explained points of significance, I immediately recognized them, and a certain familiarity from the associations would arise in my mind. When I practiced my reading on the Son Teachings, Ngakrampa would at the beginning explain some of the incidents in the stories. Then, as I continued reading, I was able to understand roughly most of the other episodes and the meaning of the easier verses on my own. Likewise, when memorizing the monastery’s traditional prayers, I found myself for the most part able to understand roughly the meaning expressed in the aspiration prayer that concludes Śāntideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. Considering my age, this seems to indicate that I was intelligent, at least to some degree.

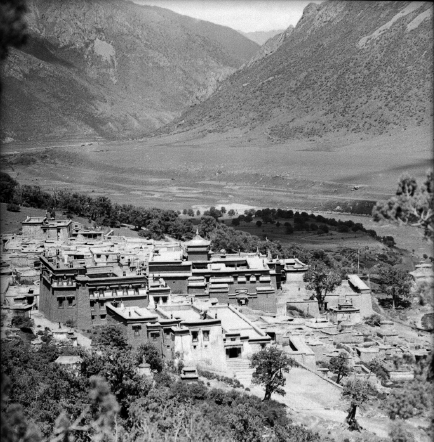

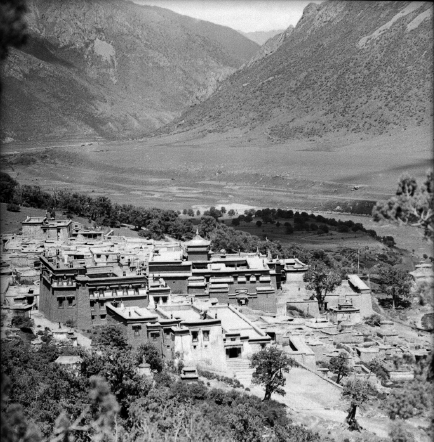

Radreng Monastery, 1950

© HUGH RICHARDSON, PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD; 2001.59.2.52.1

While we were at Radreng, the monastery’s administration had us stay in their reception room on the mezzanine and extended to our entire entourage the most cordial hospitality, seeking to provide for our every need and comfort with the utmost consideration. On the way back to Chusang, we spent a night at Taklung, a Kagyü monastery, and I visited the chapels on each floor of its temple. There I saw a most amazing thing: a statue of Dromtönpa with hair growing on its head. After that, we went to Dromtö, passing on the way Thangsak Ganden Chökhor and other monasteries. Radreng Monastery had given us so much yogurt that it lasted until Dromtö. We carried it in leather pouches and made it into a paste with roasted barley flour. Finally, we returned to Chusang Hermitage.

MY MOTHER’S DIFFICULTIES

Just before I left for the sojourn at Radreng, my father had died. Secretary Tenzin Wangpo and the other lay and monk officials residing at Kunsangtsé in Lhasa chose trustees from Gungthang for my father’s estate. The trustees were a relative of my father named Ani Yangzom and her husband, a man from Kham named Bapa Apho. Those two wrote letters to Secretary Tenzin Wangpo, who was also manager of Kunsangtsé, to Rinchen Wangyal, who was an important member of the Khemé family, and to other influential people in an attempt to prejudice them against my mother. These letters made the accusation that my mother had secretly accumulated a great deal of wealth. My elder sister, Kalsang Drölma, not only failed to douse the fire of this accusation, she fueled the flames. Thus Apho-la suddenly appeared one day at my mother’s house in Gungthang Chökhor Ling, locked the doors, and legally prevented anyone from entering. Now evicted, my mother and her two other children went to stay for a few days with Uncle Gyatso, who provided them with food and shelter. This was quite similar to the situation of Jetsun Milarepa’s mother, Nyangtsa Kargyen, and her sister, Treta Gönkyi, who also suffered the hardship of their relations turning against them.

As soon as the news of this situation in Gungthang reached my labrang in Lhasa, my treasurer, Chisur Lekshé Gyatso, personally went to see the officials at Kunsangtsé and explained in detail what he believed to be the true factors underlying this unfortunate situation. Finally the seal on the door of my mother’s house was broken and her possessions carefully examined. There was no secret accumulation of wealth as the trustees had claimed, and so the truth was revealed. On returning to Chusang, I heard about my mother’s difficulties and became quite upset and worried.

MY ENROLLMENT AT GANDEN

During the summer retreat that year I was going to enroll at Ganden Monastery. Ngakrampa, who was well versed in astrology and accomplished in ritual procedures, did everything that was necessary to counteract negative astrological forces that might interfere with my enrollment and to remove any obstructions that might block favorable astrological influences.

On the third day of the seventh month, I left my residence in Lhasa accompanied by Ngakrampa, the treasurer Chisur, Mr. Lokhé, a monastic official named Jangchup Norsang, who represented the Dalai Lama, and several others. We set out in procession for Ganden Monastery, decked in the finest of clothing on caparisoned horses.

My late father’s Gungthang estate was on our route and by all rights should have been obliged to extend hospitality to us and serve as a way station for the night, but because of the machinations of Ani Yangzom, we were not received at all and so spent the night atop the Chötri College of Gungthang. On that particular day my horse had been outfitted with a golden saddle, silk brocade caparison, and ornaments, while I myself wore an “eye of the crow” riding robe27 and a wide-brimmed gilt lacquer hat. Being a child, I was more than happy to display such regalia.

The next day we left Gungthang and traveled to Dechen Sang-ngak Khar, where we spent the night atop the branch of Gyümé Tantric College located there. The college gave us an elaborate welcoming reception, and some friends and well-wishers who lived in that region came to present me with traditional greeting scarves and gifts. We spent the next day in the foothills of Ganden and camped that night in the willow grove of Songkhar, where monks from Samling residing at Dokhang House in Ganden Monastery had pitched a tent for us to stay in and had prepared food and drink.

The following day we left at sunrise. When we reached the Serkhang estate, we were greeted with an elaborate reception that had been set up in the courtyard there by Dokhang House. It was attended by the housemaster, administrators, and many others. They gave me the traditional rice and tea and presented me with greeting scarves and symbolic offerings of the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha.28

On the previous day I had been told many threatening stories to the effect that the housemaster of Dokhang was an extremely hot-tempered man and would beat little boys at the slightest provocation. When I saw him in the flesh, however, I realized that this bearded, dark-complexioned monk with padded shoulders was not really as he had been described to me, and so I was not afraid.

After this reception we continued on until reaching a grove in Tsangthok where Shartsé College of Ganden had erected a reception tent and had made elaborate preparations to receive us. The entire administrations of Shartsé and Jangtsé colleges, including the incumbent and emeritus abbots, the reincarnate masters of both colleges and the various houses, and the complete working staff of the monastery, had come to greet us and were standing in line, scarves in hand, outside the entrance of the reception tent. Amid all these people was Gajang Tridak Rinpoché. As soon as I met him, without the need for any introduction, I thought to myself, “This is Tridak Rinpoché,” as if I were meeting someone I had known previously. From the reception lines, representatives of Shartsé College presented me with tea, ceremonial rice, scarves, and traditional offerings. Representatives of the overall monastic administration and colleges also presented me with these traditional offerings. Then the tulkus and the monastic staff who had come to greet me, all dressed in their finest robes, formed a line with their horses and accompanied us in a formal procession.

When we reached the top of Mount Drok, we came to the reception tent that had been set up by the administrators of the monastery as a whole. Preparations had been made to greet us, and so we took our respective positions as before. Tea and ceremonial rice were offered, and the abbots of Jangtsé and Shartsé colleges, in their capacity as representatives of the overall monastic administration, presented me with traditional offerings. Then we descended the mountain in a procession ordered according to rank. As we approached a spring near Ganden Monastery, a vast number of monks from Ganden’s two colleges, all holding ceremonial banners, were arrayed on either side of the path stretching from there to the great assembly hall located in front of the monastery. Upon reaching the spring, I dismounted onto a fringed red carpet and made three fully extended prostrations toward the monastery. Then I threw some grain in that direction while reciting customary auspicious verses that Ngakrampa had taught me.

Accompanied by those who had come to greet me, all holding incense, I proceeded to the assembly hall of Dokhang House. Again they formed lines, and representatives of Ganden’s administration, the two colleges, and the various houses presented me with traditional offerings. Dokhang House then gave a reception with an elaborate feast at which tea, rice, ceremonial cookies, and lunch were served to all. During the reception two students of dialectics debated on logic before the entire assembly.

After the reception I went to my suite atop Dokhang House, and there many individuals as well as representatives of various groups presented me with tea, rice, symbolic offerings of the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind, greeting scarves, and so on. When all this had come to an end, I went up to the roof. As I gazed out I saw the great assembly hall, the debating courtyards, and the long streaming prayer flags. It was all in reality exactly as I had pictured it when, at Chusang Hermitage, I had heard talk of Ganden.

Following the established traditions, a few days later I was taken by the headmaster of the house to pay my respects at the feet of the incumbent Ganden Throneholder, Losang Tenpai Gyaltsen, the third reincarnation of Tsemönling Rinpoché. Then in the presence of the abbot of Shartsé College, Losang Khyenrap of Phukhang, I made offerings of tea and money and paid homage to the assembled monks of Ganden as well as to those of my college.

Then I formally enrolled in the monastery. Tsemönling Rinpoché, the precious throneholder, was invited to preside over this ceremony with the monastery’s entire assembly of monks, and I presented him with offerings of the three representations.29 A personal emissary of the Dalai Lama served me tea from a silver pot and presented me with a stack of five “donkey ear” cookies and a protection cord that had been knotted by the Dalai Lama. After that, representatives of the monastic administration, the college, and the various houses as well as other well-wishers and relatives formally congratulated me. Also, Kyabjé Phabongkha Rinpoché extended the kindness of sending his personal representative to present me with a congratulatory ceremonial scarf and rolls of silk and brocade.

Later, according to the wishes of Ngakrampa, I entered the regimen of Lekshé Kundrok Ling Dialectics School in Ganden Shartsé College. On this occasion enormous platters heaped with dried fruit were distributed to the assembled monks. From then on I attended the daily prayer assemblies of the monastery and the college, particularly the morning and evening debates, without ever missing a session. As I had previously memorized most of the prayers and rituals, I was able to participate in all the recitations except for the supplications to the lineage of abbots and the evening ritual for Tārā, the deity of enlightened activity.

MEETING WITH MINISTER SHEDRAWA

One day soon after my enrollment, there was a flurry of activity in the labrang. I was told that the retired cabinet minister Shedrawa30 was coming to visit me and that preparations were being made to receive him. Soon he appeared, a portly nobleman whose balding head was crowned by a braided wreath of the little hair he still possessed. He wore an elegant gown of light blue silk brocade and looked very dignified. He presented me with a greeting scarf and gifts to congratulate me on my enrollment. Because I was so young, I could not think of anything to say, and so I just sat there stiffly. Shedrawa and Ngakrampa, however, were well acquainted and so spent quite a while recounting old times. Finally Shedrawa turned to me and said, “You are the best of everything, the yolk of the egg, the crown jewel of the Ganden lineage. You must therefore apply yourself well to your studies.” He proffered much advice along these lines.

The Shedra family was a special patron of Ganden from ancient times and the patron of Dokhang House in particular. After Shedrawa had become the prime minister, he therefore visited me whenever he came to Ganden on official visits accompanying His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. While Shedrawa was serving as a member of the council of ministers, he was placed under house arrest along with Shölkhangpa, Changkhyimpa, and Horkhangpa and confined to his residence in the Norbulingka Palace in the water-hare year (1903). This command came from His Holiness through the National Assembly. His Holiness the Dalai Lama may have made this decision for other reasons, but the apparent circumstances for Shedrawa’s arrest were caused by a few jealous palace attendants of His Holiness. Later, Horkhangpa escaped to Kyichu, and the others, including Shedrawa, Shölkhangpa, and Changkhyimpa, were demoted from their cabinet posts and sent into exile but permitted to stay on their respective country estates. However, Shedrawa was ordered to stay in Orong in Kongpo. When the British army arrived in Chushur, a place near Lhasa, through Tsang province in the wood-dragon year (1904), His Holiness had to make a sudden visit to Mongolia and China. At that time a high Chinese official, General Zhang Yintang, arrived in Lhasa and insisted that Shedrawa return to Lhasa to serve in the government. Shedrawa responded and returned from Kongpo. He resided at Lower Shedra, a family estate at the foot of Ganden Monastery. While Shedrawa was residing at that house, he insisted that, as the Dalai Lama had sent him into exile, it would not be proper for him to return to active government duty against the wishes of His Holiness.

It is clear from ancient records, such as the biography of Jé Tsongkhapa, that Shedra used to be called Sharhor. Later at the time of the Minister Shedra Desi, the name was changed to Lower Shedra as an improvement. The Shedra family had been personal patrons of Jé Tsongkhapa, and their mansion contained many relics of Jé Tsongkhapa, including his personal copy of the Kangyur, the canonical scriptures. As such it was the exclusive privilege of the Shedra family to provide the daily inner offering in the chapel of the protector Dharmarāja at Ganden. Not long after, His Holiness sent a letter of pardon from China, and subsequently Shedrawa, Shölkhangpa, and Changkhyimpa were reappointed to posts at the ministerial level. Thus Shedrawa continued to serve in the government.

RETURNING TO CHUSANG

I left Ganden when the rainy-season retreat was over. On the way home we spent a little time at a reception that the Gongkotsang family of Dechen had arranged for me in a meadow in front of the Kharap Shankha estate. Afterward we spent the night at the monastic labrang of Sang-ngak Khar in Dechen. While there, the residents of our Lamotsé household in Dechen and others associated with it came to greet me with gifts. Then, further along the way, the entire monastery of Chötri at Gungthang were having their annual outdoor picnic in Jarak Park. They had pitched their assembly tent, and a performance of a dramatic opera depicting the story of Drimé Kunden31 was underway. I briefly broke my journey there and watched the performance. As this was the first performance of that type that I had ever seen, I wanted to stay longer to enjoy it, but instead we proceeded to Lhasa that same afternoon.

It was required that I have an inaugural audience and interview with His Holiness after formally enrolling at Ganden. But as His Holiness had not yet returned to Lhasa from his journey to China and Mongolia, I petitioned the great throne in the sunlight room atop the Potala, in accordance with tradition. On the same occasion, I also had my inaugural audience with the regent, the former Ganden Throneholder Losang Gyaltsen Rinpoché, who was living in a residence on top of Meru Monastery in Lhasa.32

After arriving at my hermitage in Chusang, we held an outdoor picnic for two days in celebration of the completion of my enrollment activities at Ganden. A large assembly tent was pitched in our courtyard for religious activities, to which we invited the Most Venerable Kyabjé Phabongkha and Dromtö Geshé Rinpoché, the spiritual head of the hermitage, together with other resident monks. A small tent had been put up separately for myself and Demo Rinpoché, and we enjoyed playing games together. At the request of Ngakrampa, Kyabjé Phabongkha gave me the complete set of permissions for the cycle of Mañjuśrī teachings.33 Although this series of permissions requires prior initiation into the highest yoga class of tantra, Kyabjé Phabongkha nevertheless gave the entire series exclusively to me for reasons of auspiciousness. He did this even though I had not yet received the initiation of Vajrabhairava or any other deity of this highest class.

I was too young to comprehend the entire exposition given by Kyabjé Phabongkha but remember quite distinctly a story Rinpoché told me during the permission of Dharmarāja. The story was of a lama in the past, Thoyön Lama Döndrup Gyaltsen, who when conducting the same permission, found that one of the implements — Dharmarāja’s club in the shape of the upper part of a human body adorned with a skull — was not available, and so he improvised by using a chopstick with a Tibetan dumpling stuck on top. I also remember repeating after Rinpoché “I will act accordingly” a few times during the ritual.

Another time, at the request of Ngakrampa, Kyabjé Phabongkha was invited to our house and explained the measurements for diagrams of various designs used in the tantric ritual for consecrating the ground, in which different kinds of food offering substances are burned in an open flame. The instructions on these designs included four methods of accomplishment: Peace, Increase, Power, and Wrath. Except for some complicated measurements of the fire hearth related to power, I was able to comprehend these instructions quickly.

Undoubtedly, it was out of special consideration and regard for me that Kyabjé Phabongkha bestowed the above-mentioned permissions for the cycle of Mañjuśrī teachings without requiring me to have received prior initiation into the highest class of tantra. However, I did not let it suffice. As my own qualifications were known to me, I received the entire set of permissions once again from Rinpoché, complying with all the requirements, when I reached the age of twenty-one.

CHOOSING A TUTOR

As I was in need of a regular tutor, Ngakrampa and my manager discussed a possible candidate from among a number of qualified scholars at my monastic college, Shartsé, in Ganden. They presented a list of names to Kyabjé Phabongkha and to the protector Shukden for consultation and divination for the final choice of my tutor. Both Rinpoché and the protector oracle reached a decision on the same candidate, my venerable teacher Losang Tsultrim of Phukhang House in Ganden, who was from Nangsang, a town in eastern Tibet.

In the tenth month of that year, my teacher and another monk, Dosam Nyitso Trinlé, were invited to our retreat house at Chusang. On an auspicious date determined by astrological calculations, he began to teach me. First we had a ceremony for my teacher and offered him tea and the traditional rice and scarf together with a token gift. After the ceremony my teacher started to teach me the homage verses from Ratö Monastery’s34 elementary logic textbook. I also recited for him from memory the entire text of the Ornament of Realization and about half of Entering the Middle Way. My teacher was greatly pleased with my memorization of these texts.

Previously, at an annual festival at Radreng Monastery called Khoryuk Chöpa, “environmental puja,” I had witnessed a most fascinating yak dance. The dancer had done nine full turns clockwise and counterclockwise on one foot. Emulating that particular scene, I did the yak dance for my teacher. In my hand I held a brass utensil used to stir the ash in a clay container that kept the teapot warm. As I waved it around, I accidentally hit the clay container, chipping it. I was a little frightened at what my teacher might say, but I did not receive any scolding as this was our first formal meeting. From that time onward my teacher and I always remained inseparable.

That year during the months of the winter session, we returned to Ganden, and having been trained in elementary logic, I formally began to engage in the debates for solving the riddles of logic regarding color formulae.35 Thereafter followed four years of progressive training in elementary, intermediate, and advanced logic. From the start of my formal studies until my candidacy for the geshé examination, I never missed attending the annual winter sessions, the extracurricular summer sessions at Sangphu, and the annual Great Prayer Festival in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa.

RECEIVING THE KĀLACAKRA INITIATION

In my eighth year, the year of the earth-monkey (1908), at the request of the Kālacakra ritual group of Ganden, a most accomplished and highly realized master, Serkong Dorjé Chang Ngawang Tsultrim Dönden of Ganden, gave the complete three-day initiation into the deity Kālacakra in the Karmo general assembly hall at Ganden. I had the good fortune of being allowed to receive the initiation at his feet. Attendance at the initiation was so great that all the disciples could not fit into the large assembly hall, and people had to be seated in the corridors and vestibule. I was seated in front of the mandala altar behind the most venerable Kyabjé Khangsar Rinpoché36 of Gomang College of Drepung Monastery. Serkong Rinpoché selected me to sit in the center of the purification diagrams, drawn on cloth, during the vase-initiation stage. This purification ritual is performed for novices. Whether or not Serkong Rinpoché did so for auspicious reasons, he also gave me the eye lotion used in the ritual for clarity of wisdom. The lotion contained honey, among other ingredients, and was so delicious that I ate it all. During the initiation it was most spectacular to watch some of the monks from Namgyal Monastery of the Potala Palace, His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s ritual institute, performing in full tantric regalia. They each held decorated vases and chanted melodiously the verses for prosperity and auspiciousness.

Because of my immaturity I did not understand most of Rinpoché’s explanations during the initiation, but I did notice his moving, expressive moods. At times tears would well up in his eyes as he explained the teachings in great detail. The next moment he would be scolding the disciples, or unexpectedly telling jokes, causing laughter. The next day, following the initiation, Rinpoché announced to the gathering that they could feel confident, without any doubt, that they each had received the initiation in its full meaning. In ancient times disciples used to receive initiation and proper blessing for their spiritual realizations with a mere slap on the cheek from a realized tantric master. Although it is difficult for this to happen nowadays, considering the type of disciples there are, without any doubt the special instructions left an impression on our mindstreams due to the power of being directed through the visualizations by such a great, realized lama.

BEING AWARDED THE FIRST ACADEMIC DEGREE

In my ninth year, the year of the earth-bird (1909), during the annual session of the disciplinarian37 at my college, I was conferred the degree of kachu (covering ten subjects), and I was required to recite passages from any treatise that I had studied. At this ceremony my monastic household made offerings to the monks, and I recited by heart two pages from Jé Tsongkhapa’s Essence of Eloquence Distinguishing the Definitive and Interpretive.38 Everyone present at the ceremony congratulated me and commented on how well I had recited without any hesitation or nervousness despite my age. In celebration of my kachu examination, we also made extensive offerings to my main monastic house and to the other regional monastic groups with which I was affiliated.

About this time, Lhabu, who was a son of dairyman Tashi Döndrup from the pastoral region Balamshar in Dechen, arrived to become a permanent member of our labrang. He was ten years old and so became my playmate. From then on, until his death at the age of sixty-six, he served as my closest attendant. He looked after me in accordance with the finest examples of a disciple’s dedicated service to his teacher as illustrated in the Marvelous Array Sutra with the analogies of a boat and a solid foundation, and conduct as firm as a vajra and a mountain. I am very grateful for his kind service.39