CARED FOR WHILE ILL BY TRIDAK RINPOCHÉ

IN MY TWENTY-NINTH YEAR, the year of the earth-snake (1929), I offered tea and three sho to the monks at the Great Prayer Festival. After the festival I made offerings to the assemblies of Drepung and Sera monasteries, to Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges, and to the monks and nuns at Chusang Hermitage. At Gyütö Tantric College I presented 150 sets of five-buddha-family headdresses, which were made specially to order to match and coated with Chinese lacquer.

That year at Chusang, at the feet of Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara, I had the good fortune to receive oral teachings on the Guru Puja and mahāmudrā based on the great commentary on the Guru Puja and the root text of mahāmudrā, as well as a teaching on the generation and completion stages of thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava once again, along with many other discourses.

In my thirtieth year, the year of the iron-horse (1930), a senior staff member of the Gungthang estate, Makdrung Kalsang, established the ritual offering and practice of Vajrabhairava and restored the practice of the five-deity Cakrasaṃvara at Chötri Monastery. In order to undertake these activities, he asked that I give initiations into the deities. Although I was suffering discomfort from a kidney ailment at that time, at Makdrung Kalsang’s wish, I went to Gungthang and gave the initiations, after which my condition became worse. After crossing the Brahmāputra both ways during the journey, my condition became quite serious, and later I suffered a kidney infection and swelling in the leg. I was bedridden, unable to leave my room, until the beginning of the eleventh month and suffered a great deal of difficulty.

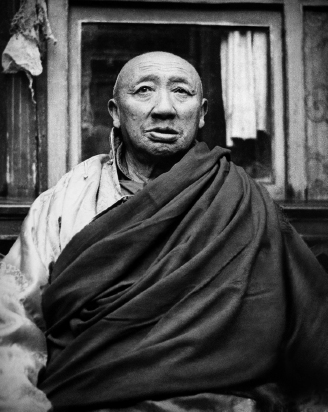

At this time Tridak Rinpoché of Ganden Jangtsé visited me often and performed many rituals to avert the circumstances of my sickness, such as purification and nāga rituals. He also gave me permission for the practice of Striped Garuḍa and advised me to do a mantra recitation retreat for that deity. After completing the retreat according to his advice, I dreamed one night that I transformed into a striped garuḍa the size of a sheep and landed on the roof of my house. I also dreamed of a platter with many frogs on it. The platter was covered with a cloth, the ends of which I held tightly beneath the platter with my left hand. The movement of the frogs on the platter lifted the cloth cover, and when I peered into the platter by lifting one end of the cloth, two frogs leaped out, and the rest of them became soft and mushy. The skins of their backs stuck to the cloth cover, and I could see fresh red sores on their backs. I interpreted this dream as pacification of the affliction caused by spirits. I received treatment both from Dr. Jikmé of Shelkar and Kalsang-la, a teacher of medicine at the Chakpori Medical College, and recovered gradually, ignoring the beckoning of the lord of death.

Tridak Rinpoché, the incarnation of Tridakpo Ngawang Tashi, was well educated in both sutra and tantra. Not only was he well versed in poetry, literature, and Sanskrit, he was also proficient in the ritual activities of the four classes of tantra and in the diagrams and colors of the mandalas, and he was able to paint thangkas on his own. Rinpoché had received many teachings and initiations from Serkong Dorjé Chang and Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara. He was not arrogant and never boasted about his knowledge; nor did he act as ordinary lamas do, advertising the little knowledge they have to others as if waving a flag. His demeanor was like a flame kindled in a container.

Since Rinpoché and I were the disciples of the same lama, we were intimately connected. Though I knew that Rinpoché had received important secret oral teachings from Serkong Dorjé Chang, as the proverb says, “The old lady of Lhasa doesn’t go to see the Buddha in Lhasa.”137 So although I had intended to receive such teachings from Rinpoché, he passed away before I could do so. I greatly regretted it, but it was too late.

THE ARRIVAL OF PALDEN TSERING

My attendant Lhabu’s father, Tashi Döndrup, who looked after our dairy farm at Dechen with great loyalty and dedication, passed away after a sickness in the earth-snake year (1929). It was his wish that his youngest son, Palden Tsering, join the service of our labrang, so that autumn Palden arrived in Lhasa with an escort. I taught Palden how to read and soon after sent him to the school in Lhasa run by Dr. Rikzin Lhundrup of Nyakrong Shar and looked after him from his childhood. As it is said:

Unspoiled although in the midst of comfort,

not wanting to run away when times are hard,

carrying out every task given, easy or difficult:

this is the epitome of a loving servant.

So it is with Palden, who has served, and continues to serve, as my personal attendant with loyalty and dedication, while ignoring any difficulties of his body, speech, and mind. He is the sole supporting cane on which this old man rests his hand.

In my thirty-first year, the year of the iron-sheep (1931), I attended most of the teachings given by Lama Vajradhara at either Chusang or Tashi Chöling Hermitage. In Lhasa, from assistant tutor Kyabjé Takdrak Vajradhara, I received initiations into Vajrabhairava according to the system of Jñānapāda and Lokeśvara according to the system of Atiśa. I also received teachings on Vajrabhairava based on the texts of Ra and Pal, and many oral transmissions, such as the practice manual of great Four-Faced Mahākāla based on the root and explanatory teaching texts. At the end of that autumn, two representatives of the monastery and the people of Chatreng, Phagé Losang Yeshé of Upper Chagong and Pawo Butsa Gelong Tenpa Namgyal of Trengshok, arrived to invite me to come to Chatreng for a return visit.

THE PASSING OF THE GANDEN THRONEHOLDER AND GESHÉ NGAWANG LOSANG

In my thirty-second year, the year of the water-monkey (1932), Chinese soldiers infiltrated through the Ba area of Kham, and the Tibetan border security forces, not able to hold them back, lost territory all the way up to Bum Lakha in Markham. Because the imminent threat of war spread throughout the country, our own government was forced to acquire weapons from the British. I spent most of the summer at Chusang, receiving teachings on the various ritual ceremonies of Vajrabhairava, and many others, from Kyabjé Lama Vajradhara. In between the teachings I did several meditational retreats on various deities.

That year, in the twelfth month, the Ninety-First Ganden Throneholder, Losang Gyaltsen of Lawa House of Sera Jé, passed away. Although I hadn’t yet been called for by the throneholder’s manager and staff, of his own accord His Holiness the Dalai Lama dispatched a horse groomer from Norbulingka as a messenger to fetch me. When I arrived there, I was instructed by his attendant, Thupten Kunphel, that the throneholder had passed away the previous day and that I should assist in the ritual bathing of his body as well as in the cremation and so forth. I immediately proceeded to Phurchok Labrang, where the throneholder had been staying, and found that the ritual master from Namgyal Monastery, Sönam-la, was already there. His Holiness had instructed him that he and Trijang Tulku should do what was needed and that Phurchok Tulku Rinpoché should pay careful attention to the procedures in order to acquire personal experience for his future use. In retrospect, I realized that this was done for a very special reason: His Holiness had foreseen with his clairvoyance that Phurchok Rinpoché and others, including myself, would also have to attend to the service of His Holiness’s body when His Holiness’s thoughts passed into the state of peace the following year.

In accord with His Holiness’s wishes, we performed ritual bathing and self-initiation until the body of the Ganden Throneholder was ready to be cremated. Then I presided over the cremation ritual according to the writings of Thuken Chökyi Nyima at Phabongkha Hermitage. Phurchok Rinpoché came to observe the ritual bathing and such throughout the procedure.

In my thirty-third year, the year of the water-bird (1933), His Holiness paid a visit to Ganden Monastery during the special session at Taktsé after the annual Great Prayer Festival in Lhasa. Not daring to stay in Lhasa during his visit, I immediately left for Ganden and proceeded to participate in the Vajrabhairava ritual offerings organized by Shartsé College. I had a private audience with His Holiness in the Clear Light Chamber138 at the Ganden Throneholder’s living quarters. There His Holiness conveyed his esteemed regards to me, and I answered his questions concerning the ritual sessions that Ganden celebrated in accordance with ancient custom. After His Holiness left Ganden, I returned to Lhasa.

When I had departed for Ganden, my former classmate, Geshé Ngawang Losang of Phukhang House, whose scholarship was recognized in the three seats of learning, was sick with a fever at my house in Lhasa. When I had studied at the monastery, he had been my debate partner, and he had been a very close friend for many years. He passed away before my return to Lhasa, and I had tremendous regret at not having been able to see him at the time of his death. I made extensive offerings on his behalf.

At the end of summer, I invited Kyabjé Phabongkha to my residence at Chusang, and we were in the process of receiving permission for the seventeen emanations of Four-Faced Mahākāla139 when a messenger specially dispatched from the stable of the Norbulingka Palace arrived with a message that I should report to the sunlight room at the Norbulingka early the next morning. I went to the Norbulingka and received through Kunphel-la the holy command, as per a letter submitted to His Holiness by the monastery and people of Chatreng requesting his consent and permission to grant me a leave of absence, that I should leave immediately for Chatreng. There I should give advice and counsel to the people to serve and support the Dharma and secular affairs. I was also told to send reports to His Holiness in the event of possible schemes for Chinese invasion. I received extensive instructions on other aspects of my activities there.

Because pack and transportation animals had not been prepared for our immediate departure, I sought and received permission to leave promptly the following year. The three permissions for the cycle of Four-Faced Mahākāla and the secret teaching of Mahākāla that I had not received were later given to me by Kyabjé Simok Rinpoché of Nalendra Monastery in Phenpo district. In preparation for my trip to Kham, I sent Losang Yeshé, one of the delegates from Chatreng, to India and instructed him to buy supplies there.

THE PASSING OF HIS HOLINESS THE THIRTEENTH DALAI LAMA

In 1933, on the thirtieth of the tenth Tibetan month, His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama passed his thoughts into the state of peace. Phurchok Jamgön Rinpoché, assistant tutor Takdrak Vajradhara, assistant tutor Gyalwang Tulku of Kongpo House of Sera Mé, Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, and myself, along with the master of chant and the ritual master of Namgyal Monastery, tended to the ritual procedures for the bathing and preservation of his body. I had to postpone my journey to Kham. The body of His Holiness was taken to the Sishi Palbar Chamber in the top-floor sunlight room in the Norbulingka Palace, and we started the ritual for the consecration of his body, which included bathing his body and every week changing the salt crystals in which it was kept.

Over the following days an investigation into the causes and circumstances of His Holiness’s sickness and its outcome was held by the National Assembly in the Norbulingka Palace. His Holiness’s attendants, including Thupten Kunphel and his physician Jampa-la, were questioned by the National Assembly about the circumstances of his death and the treatment of his illness. After this interrogation they were put under arrest and imprisoned. Thupten Kunphel was sent to Kongpo and the others to various places of exile.

In the twelfth month, the holy body of His Holiness was brought to the Ganden Nangsal Chamber in the east wing of the Potala Palace. From then on, every day for a year and a half until prayers and relics could be placed in a newly constructed golden stupa, I tended the ritual procedures of making offerings before his body. The newly appointed regent, Radreng Rinpoché,140 and Prime Minister Yapshi Langdun Gung Kunga Wangchuk also charged us with the responsibility of drawing up plans and measurements for the memorial stupa as well as gathering the prayers and materials to be inserted in it.

When we made the diagrams for the proportions of the stupa on cloth, we laid the cloth in the vast courtyard of Deyang Shar on the east side of the Potala. We made the size of the stupa two arm lengths’ larger than His Holiness the Fifth Dalai Lama’s memorial stupa, the Sole Ornament of the World. The evergreen tree trunk that arrived from Radreng Monastery for the central wooden support was exactly the same size as the measurement in our plan, reaching from the top of the stupa to the lotus seat of the vase,141 without so much as an inch difference. It was an amazing occurrence of unplanned auspiciousness. In general, the length of the wooden support for a stupa should extend from the top to the lotus petals at the base, but when the wooden support is conjoined with a mandala according to the Two Stainless Cycles,142 the mandala diagram is to be placed at the base of the vase and the wooden support securely planted there. It was this system that we used on that occasion.

While engaged in service of His Holiness’s body during my thirty-fourth year, the year of the wood-dog (1934), our manager Rikzin suddenly suffered a stroke and passed away. My attendant Lhabu and I were forced to assume responsibility for making offerings and other activities following his death. As mentioned earlier, due to lack of sufficient knowledge, ability, and success, there was a shortage of grain and other necessities at our labrang. Sometimes we were even forced to borrow from neighbors when our own supplies from our village farm estates did not come in time. With our supply of butter depleted prior to the end of the year, we had to take advance supplies from dairy farms. As our cellar storerooms only contained dried yak dung,143 empty leather cases used for packing butter, and empty wooden boxes, we suffered great hardship for a few months due to the shortage of necessities. As Lhabu and I lacked the competence “to sacrifice a hundred in anticipation of gaining a thousand,” we weren’t fit to manage anything. Yet by the blessings and grace of the Triple Refuge, the status of our financial resources improved year by year, and prosperity began to return. We were able to make offerings to the objects of refuge and the monks to our hearts’ content, as if drawing water from a well whose volume only seems to increase.

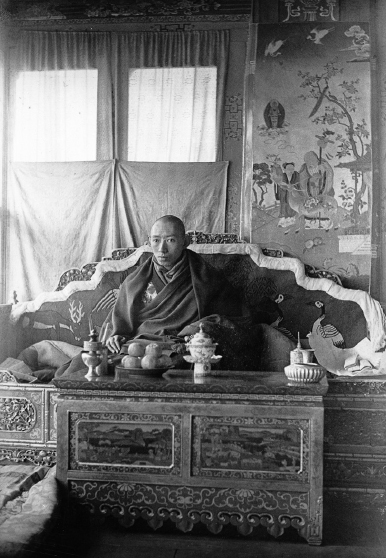

Regent Radreng Rinpoché at Shidé Monastery, 1937

© FREDERICK SPENCER-CHAPMAN, PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD; 1998.131.516

That year the finance minister, Lungshar Dorjé Tsegyal, and the cabinet minister Trimön Norbu Wangyal came into conflict over a disagreement with respect to governmental power and authority, which led to unrest due to factional disputes among the monastic and lay government officials as the two solicited supporters. Lungshar was arrested, and on the eighth of the fourth month, both his eyes were gouged out at the Shöl Court hearing at the base of the Potala. He was sentenced to life in prison, and some of his friends were exiled to distant estates in various districts.

Both Lungshar and Kunphel-la were well known and powerful due to the special regard that His Holiness had had for them. Kunphel-la was someone whose moods all government officials, whether high, medium, or low, had to pay attention to. Although he was someone whose words even the various political offices had to take special notice of, as it says in the Vinaya, “All compounded things are subject to decline, ruin, dispersion, and change.” Both men, along with their associates and relatives, suffered sudden tremendous change. Having seen the happiness and suffering of cyclic existence and that prosperity and adversity flicker like lightning, I felt sorrow, and my renunciation increased.

While coming to the Potala every day to perform the ritual of consecrating the body and changing the salt once a week, in the autumn we began to arrange the prayers and relics to be inserted into statues and stupas. Master craftsmen constructed the wooden structures that would form the base of the golden reliquary.

Concerning the placement of mantras inside the mausoleum: among existing blockprints of protective spells, the ones that contained the widest variety of mantras were from the blocks made during the time of Desi Sangyé Gyatso. First we placed in their appropriate places, without error, the five types of great dhāraṇī, printed at the dhāraṇī printer behind the rear exit of the Potala known as Kagyama, into the places indicated for the upper, middle, and lower dhāraṇī, and diagrams of male and female yakṣas, in accord with the thought of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama’s Sun Dispelling Errors in the Placement of Dhāraṇī144 and Changkya’s Crystal Mirror.145

We placed on boards within the base of the stupa treasure vases related to Yellow Jambhala, White Jambhala, Vaiśravaṇa, Vasudhārā, Pṛthivīdevatī, and the five buddha families as written in the catalog of Sole Ornament of the World — the Great Fifth Dalai Lama’s Golden Stupa.

At the four corners and in the center of the lion-throne portion of the stupa, we placed box representations of Six-Arm Mahākāla, Dharmarāja, Palden Lhamo, Yakṣa Chamdral, and the five emanations of Nechung Dharmarāja. Inside of each we placed life-stone and life-force diagram supports for each protector; representations of body, speech, mind, qualities, activity, and so on; outer, inner, and secret representations; thread-cross supports and the various substances; and mantras and petitions to establish and consecrate it as stated in the various manuals.

Within the sun and moon ornaments at the pinnacle of the reliquary, we drew the miktsema diagram for pacification, increase, and subjugation; the diagram for gathering disciples; the diagram of Sitātapatrā for protecting the country; the sādhana of Jetsun Kurukulle, first among the great red goddesses among the Thirteen Golden Dharmas of glorious Sakya; Flow of the River Ganges: Instructions on the Key Points to Conquer the Three Realms by Tsarchen;146 the diagram that grants one power as taught in Dakpo Tashi Namgyal’s Source of Siddhi;147 the diagram for controlling the three realms; and the diagram for accomplishing all aims. We drew a large Gaṇeśa as written in the Wish-Fulfilling Tree148 in the manner of Mahārakta Gaṇapati, the second deity of initiation, to accomplish the four activities of the secret essence diagram. For each of the diagrams of initiation, we stacked three diagrams one on top of the other. For the third deity of initiation, the wrathful Kakchöl, we drew mother and father diagrams as written in Kāmarāja’s Blazing Jewel Sādhana.149 Nine diagrams of the sun, moon, and so on, which fall on the vital places, were stacked above and below.

The drawing surfaces, the substances to be applied, the time to draw the diagrams, the accomplishment, and so on were carried out according to the unerring arrangement found in the Great Fifth Dalai Lama’s Bouquet of Red Utpalas: Instructions to Undo the Knots of the Difficult Points of the Three Cycles of Red Ones150 and Hook to Summon the Three Realms: Illumination of Diagrams.151 The “requesting to stay” rituals are recorded in the catalog of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s Great Golden Stupa, Granting All Goodness and Happiness.

In order to collect the materials to be inserted into the reliquary, approximately fifty sacred cases that were the property of the government and that contained self-produced relics of great realized beings from ancient India and Tibet, including their clothes, hair, bones, ashes, and many other wondrous and inconceivably precious relics, were opened in the Ganden Yangtsé Chamber of the Potala Palace in the presence of Regent Radreng Rinpoché, Prime Minister Yapshi Langdun Gung Kunga Wangchuk,152 Cabinet Minister Trimön, the overseer of the reliquary project, four monastic governmental secretaries from the Upper Department, and those of us who were engaged in the ritual services of His Holiness’s body.

A portion of each relic was made ready, presented, and inserted into the appropriate places in the various sections of the structure of the stupa. Each of us who were engaged in service to His Holiness’s body were fortunate to obtain as a gift some small bits of relics. Later, as I will mention below, I came to acquire indisputably authentic relics from various monasteries during my extensive pilgrimage to holy places of Central Tibet such as the district Lhokha. I retained these with great care, as they were the most extraordinary jewels, ones that one cannot obtain on any plane of existence. I brought them with me during my flight from Tibet to India to seek asylum in the Tibetan Royal Year of 2086, the earth-pig year, 1959. Except for a small portion of the relics for my labrang, I presented the bulk of them to His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, with a complete catalog and in labeled packages, for their perpetual use as objects in relation to which beings may accumulate merit.

We frequently changed the salt around the body of His Holiness. When the moisture of the body had nearly dried up and the body became more and more skeletal as the flesh reduced, a self-emerged image of Avalokiteśvara three inches in height, with head, hands, and feet, as well as a lotus seat, appeared very clearly on the surface of his back at the thirteenth vertebra. The sight of this filled me with great admiration and profound faith.

In the third month of my thirty-fifth year, the year of the wood-pig (1935), we completed the interment of materials in all parts of the stupa except for the vase structure. We placed ritual prayers of Sitātapatrā and miktsema into the gilded victory banners on the roof of the temple that would house the stupa, placed rituals of Palden Lhamo, Chamsing, and others into various adornments of the stupa, and placed protective spells into the jewel top of the gilt roof.

On an auspicious day in the month of Buddha Śākyamuni’s enlightenment, the body of His Holiness was adorned with the three sets of monastic robes, crowned with the diadem of the five buddha families in the aspect of an enjoyment body, and placed inside the stupa’s vase compartment. The government celebrated this occasion with elaborate ceremonies. Following this the extensive consecration ritual of Śrī Vajrabhairava was performed over three days, presided over by Radreng Rinpoché and attended by the entire assembly of Namgyal Monastery. I also attended the entire session.

To celebrate the successful completion of construction of the Dalai Lama’s Great Golden Stupa, Granting All Goodness and Happiness, the government arranged an elaborate feast of ceremonial cookies in the Sishi Phuntsok Hall of the Potala Palace. There, Minister Trimön, the overseer of the stupa project, the overseer of construction, the craftsmen, and those of us who attended to His Holiness’s body were honored with gifts bestowed accordingly. I was given a complete set of robes, consisting of upper and lower monastic garments, a vest, ordination robes, a monastic hat, monastic boots, as well as a case of tea, brocade and silk cloth, an honorarium, and a ceremonial scarf. I considered it a great honor and the highest good fortune to participate in the noble task of serving for one and a half years with dedication and devotion: from the very start of the ritual service to the ritual preparation of the body all the way up to the completion of the Great Golden Stupa and its foundation, with sacred material placed inside and sealed with a ritual of consecration.

During the rainy-season retreat, I went to Ganden, and at the request of Phara House of Ganden Jangtsé, I gave an initiation into Akṣobhyavajra Guhyasamāja with its preparatory rite to a large number of monks from Shartsé and Jangtsé colleges in the Jangtsé assembly hall. I attended the newly established ritual offering to Guhyasamāja at Phara House for seven days.

Since I myself was unable to go to Chatreng, Pawo Butsa Gelong Tenpa Namgyal, who had been sent as a representative of the monastery to invite me, was preparing to return to Chatreng. I wanted to send with him a large appliqué thangka as an offering to the monastery. Along with the funds for our travel expenses that the monastery had sent, donations for the thangka were also offered by members of the Chatreng community living in Lhasa. Our labrang also provided food, drink, and so on for the group of master craftsmen invited to create the thangka. The appliqué thangka, three stories high, was made of good brocade and illustrated the celestial host of Tuṣita, with Jé Tsongkhapa and his two disciples emerging from the heart of Maitreya. The two previous great throneholders were depicted on the top, and on the bottom were the protectors Dharmarāja and Trinlé Gyalpo.153

THE DEATH OF LOSANG TSULTRIM

In my thirty-sixth year, the year of the fire-rat (1936), my esteemed teacher and precious mentor Losang Tsultrim, who was then sixty-seven years old, became slightly ill at the beginning of the second month. Despite relying on every possible method of treatment from the physician Jikmé of Shelkar, employing ritual offerings, and performing service and care to the best of my ability, his thoughts passed into the sphere of peace in the late afternoon on the fifteenth of the second month. My mind was tormented with unbearable grief, but as there was nothing I could do about it, I fortified myself and attended personally to his body, including the ritual bathing.

From the time I was a tender sprout at the age of seven not only did he extend to me great kindness, with untiring care in providing to me the religious instruction that has enabled this donkey to enter the ranks of humans, he took principal responsibility and gave valuable advice on secular matters following the deaths of the managers of our labrang and during that critical, most difficult phase wherein the responsibilities of the administration of the labrang had fallen to me. Even given eons the extent of the kindness he bestowed could not be measured. Although it was difficult to properly rely on my precious teacher as a spiritual friend, having been in constant companionship with him at all times, I was not the cause of any disappointment and disgust by my teacher. As the importance of properly relying on the spiritual friend is such that even the slightest mistake or act done properly can determine ruin or success, I declared openly with repentance in the presence of his body any mistakes and downfalls that may have occurred.

My teacher’s body was taken to Chusang Hermitage, where together with a few ritual assistants from the Gyütö Tantric College, I cremated his body with the ritual fire offering. Each week thereafter I made offerings at the Great Prayer Festival and the subsequent session, at Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges, at the three monastic seats, at the three centers of Dharma,154 and at other sacred places for the perpetual accomplishment of his wishes.

My late teacher was born into a family called Jarshing in the Nangsang region of Domé province in the iron-horse year of the fifteenth rabjung cycle. He enrolled in Shartsé College at Ganden, and having become a top scholar upon completion of extensive study of the five treatises, he sat for his geshé lharam examinations, receiving second position with honors. At that time, when the abbot of Shartsé, Losang Khyenrap of Phukhang House, had resigned his abbotship and was living alone, and the following abbot, Lodro Chöphel of Nyakré House, had passed away in the fifth year of his abbotship, His Holiness called “Losang Tsultrim, tutor to Trijang Tulku,” by name to appear for a debate examination and was on the verge of appointing him the abbot. At this juncture, through Deyang Tsenshap Rinpoché, assistant tutor to His Holiness, and others, my teacher requested His Holiness that he be excused from this appointment due to his poor eyesight and lack of administrative knowledge and skill. Were it anyone else, an appointment with special regard by His Holiness would be considered the ultimate attainment and would have been happily accepted without hesitation. My teacher, however, was someone who did not like occupying a high post and could not sleep for days out of worry and concern, due to which he suffered from nervous tension in his chest and back and often shed tears. Nyitso Geshé Trinlé of Chatreng had to comfort him.

Generally with regard to his daily deeds and activities, he rose early in the morning and practiced the Guru Puja, the six-session guruyoga, the sādhanas of Vajrabhairava and Medicine Buddha, as well as various other prayers. He continuously recited the miktsema, the mantra of Maitreya, and the mantra of Avalokiteśvara except while teaching or studying. He never sat idle or passed time with gossip. During his stay in Ganden, many students from both Shartsé and Jangtsé came to study with him every day and he taught them without any reluctance. Many among his students became good scholars who in turn taught others. To this day there are many geshés who descend in his line of learning. As such he performed an immense service to the Dharma and left a great legacy.

His style of teaching was such that he did not give unnecessarily extensive commentaries and instead provided concise explanations on the difficult points in a manner easy to comprehend. For example, with reference to my lessons, when I studied the Perfection of Wisdom at age twelve and thirteen, my enthusiasm and comprehension were small in scope due to my age. But with the exception of the greater topic, Tsongkhapa’s Essence of Eloquence, I was able to develop a good general understanding of the other subjects, such as going for refuge, generating bodhicitta, and the Buddha’s turning of the wheel of Dharma. This was after my teacher went over the text with me once and taught me the points of debate for a penetrating understanding of the meaning. Like chasing a hundred birds with one slingshot, I had a good basic knowledge of the topics in all stages and could reconstruct them in their proper order.

Two years after my teacher passed away, in the hope of discovering his incarnation, whom I intended to personally take care of without the publicity of an official title of incarnation and enroll him for study as an ordinary monk to repay his kindness, I consulted Sengé Gangi Lama in Phenpo district. He had done the hundred thousand mantra recitations retreat of the sādhana of Yudrönma and was someone Kyabjé Phabongkha held in high regard. Based on his mirror divination, he sent this reply in verse to my questions regarding the incarnation of my teacher:

On the full moon day, drawn up on the light-ray path

emanated from the heart of the celestial Maitreya,

he now dwells in the heaven of Tuṣita

within the entourage of Ajita Deva.

Although I did not make any mention of the time of my teacher’s passing away in my letter asking for his prediction, his reply stated that my teacher passed away at the full moon and was reborn in the celestial realm of Tuṣita. Though I had no further hope of discovering his incarnation, my faith and conviction in my teacher increased.

In the third month I went to Ganden to make offerings for my teacher, and there, at the request of Geshé Ngawang Tashi of Lhopa House in Shartsé, I gave to a large audience including the abbots of Shartsé and Jangtsé, as well as tulkus and monks, an initiation into sixty-two-deity Cakrasaṃvara according to the system of Mahāsiddha Luipa. That summer I began work on a project to make a decorative bejeweled appliqué drapery of multicolored brocade illustrating the thirty-five buddhas of confession and a depiction of the protector Setrap to be hung above the main entrance to the assembly hall. This large decorative drapery was to be hung on special occasions on all four of the inner sides of the clerestory of the hall, including the balcony. Twelve pillar banners made of Varanasi brocade with appliqué tsipar heads and twelve small hangings of triangular shape were also fabricated for Dokhang House. I went to Ganden and presented the hangings to Shartsé and Dokhang, along with tea and money offerings, during the festival of lights. I also made offerings at Jangtsé and established a capital fund for annual offerings of one tam to each monk.

In my thirty-seventh year, the year of the fire-ox (1937), I made offerings at the Great Prayer Festival to amass merit for the accomplishment of the wishes of my late teacher and to eliminate the obstacles of my twelve-year cycle. I made offerings at Gyütö Tantric College on the anniversary of the passing away of my late teacher and donated a capital fund to offer one tam every year on the fifteenth of the second month.

At the request of Lady Yangzom Tsering of the aristocratic family of Lhalu Gatsal, I constructed a shrine at the Lhalu family temple for the inner, outer, and secret objects related to the activities of the holy body, speech, and mind of the female protector goddess Palden Lhamo Maksorma, who is the aspect of Buddha’s activities for sentient beings. They were constructed in the protector chamber of the family according to authoritative sources, such as the ritual manual of the goddess and the writings of the Fifth Dalai Lama and Thuken Rinpoché. I performed the ritual for seven days.

TANTRIC TEACHINGS FROM KYABJÉ PHABONGKHA RINPOCHÉ

In the assembly hall of Chusang Retreat House, I received from Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara a detailed explanation of Candrakīrti’s Bright Lamp (Pradīpoddyotana) on the completion stage of Guhyasamāja, the secret instruction that is the best, the sublime, the ultimate pinnacle of the essence of all classes of tantra, which liberates disciples of sharp faculties from cyclic existence and delivers them onto the ground of immutable enlightenment in this very life. When we reached the explanation of the illusory body, we arranged extensive offerings of torma and tsok on the altar and offered outer, inner, and secret suchness to Lama Vajradhara conceived as the principal deity of the mandala. Then we made the request to impart the teaching on the illusory body. All this was done according to the traditions of the tantric monastery, and the offerings were well arranged. At this point I recited the following spontaneous song of joy:

Dechen Nyingpo, embodiment of all guru-buddhas,

lucidly proclaims an unending Dharma melody,

the teachings of the Glorious Guhyasamāja, the peak of all the tantras.

What delight, this fortune that even Brahmā and Indra do not attain!

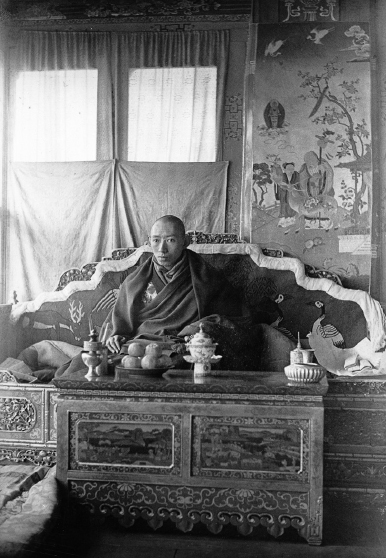

Kyabjé Phabongkha Rinpoché

ALEXANDRA DAVID-NÉEL © VILLE DE DIGNE-LES-BAINS

Although lacking the ease of a melodious voice,

help me, vajra brothers of pure pledges and bonds,

to offer as a cloud of praise that pleases the incomparable guru,

this spontaneous song of joy overflowing from our rapturous delight.

Though poor in the movements gained by skill and practice,

yet by the power of Lama Akṣobhyavajra’s blessing,

let us perform the joyful dance of the fortunate ones

on the swift path of the peerless great secret.

With the world of existence and appearance as myriad pure mandalas,

and the innate tones of the in and out breaths arising as secret mantra,

the army of the horses of the manifested wheels of the three realms

are harnessed on the path of dual abandonment. I take joy in such skill!155

The clear light of one taste with the realm of elaborations pacified

and the primordial and innate smiling youth,

a great cloud of illusion with five light rays released unhindered,

a dancer filling the vast mandalas of space.

Though appearing as a bouquet of enlightened attributes,

it is of the nature of exalted wisdom;

though existing as unobstructed exalted wisdom,

it possesses the appearance of the form body;

the joy of the stage of union, one taste appearing as many:

I yearn to dwell in the pure realm of Akaniṣṭha.

It is said that by the kindness of the siddha Indrabodhi,

many beings find freedom without relentless hardship.

E ma! Having met such an excellent and profound path,

Oḍḍiyāna must be like this, I think.

With the armor and power of patience

to free all mother living beings,

may we engage the meaning of the tantras,

garland of consonants imbued with the letter a,156

and may we thoroughly remove all stains

of erroneously clinging to duality

and sing the joyous song of a li la mo.157

Having been offered such a song, the incomparable precious guru expressed his great pleasure. Yet the fact that I lack the good fortune to materialize any of my aspirations due to being wholly entangled in distraction is certainly a result arising in accordance with unwholesome actions I performed in prior lives.

PILGRIMAGE TO SOUTHERN DISTRICT

That autumn, along with Lhabu and a few others, I left Lhasa, passing through Ganden, Maldro Katsal, Gyeteng, Cheka Monastery, Pangsa, Rinchen Ling Monastery, and Ruthok Monastery. Crossing Takar Pass, we visited Ölkha Dzingchi and Samling, and crossing Gyalong Pass we visited Chökhor Gyal, Lhamo Lhatso, Gyal Lhathok, the great temple of Daklha Gampo, and Sanglung Retreat. On the way back we went by Ölkha Chusang, Chölung, Gyasok, Lhading, and Nyima Ling. We passed a few days at the Shöl hot springs in Ölkha.

Although there were inconceivable objects of worship at Daklha Gampo,158 the statues appeared to be neglected, which was utterly depressing. I had an audience with Daklha Gampo Rinpoché, and thinking to take advantage of the opportunity, questioned him regarding mahāmudrā and the six Dharmas of Nāropa. Perhaps he was shy. At any rate, I didn’t receive satisfying replies.

We passed over Khartak Pass and visited Sangri Khangmar, Densathel, and Ön Ngari Monastery. We arrived at Tsethang having taken the Nyangpo ferry across the Tsangpo River. We visited Ngachö Monastery, Ganden Chökhor, Namgyal Temple, the congregation at Nedong Tsé, Bentsang Monastery, the chapel at Tradruk, Riwo Chöling, Yumbu Lagang, Lharu Menpai Gyalpo, one of the three sacred shrines of Yarlung, Takchen Bumpa, Tashi Chödé, Rechung Cave, Thangpoché, Songtsen’s tomb, the sacred shrine of Menla Rinchen Dawa at Chenyé Monastery, the famed sacred statue of Tönpa Tsenlek at Rigang, Chongyé Riwo Dechen, Gönthang Bumoché, Tsenthang-yu Temple, Sheldrak Cave, and Jasa Temple.

At Sheldrak, when I made offerings before the statue of Padmasambhava, it appeared to me as if the statue became increasingly magnificent, as if it were Guru Rinpoché in person. It seemed as if his eyes were moving and he was about to speak. He did not do so, despite my earnest hopes, but extraordinarily on that day, an inexpressibly joyful awareness of emptiness without reference point or reason arose within me. I understood this to be a sign of having been blessed by Orgyen, the second Buddha.

At most of the above-mentioned monasteries, I gave various teachings according to particular requests and stayed for a few days at the Khemé estate. At Riwo Chöling, I offered initiation into Akṣobhyavajra Guhyasamāja as requested by the monks. Then, on the return journey, we crossed the Tsangpo River by ferry and took in the sacred sights of Samyé. Thereafter, visiting the pilgrimage sites in upper and lower Chimphu and Yamalung, we made thousandfold offerings, a hundred lamps, tsok, and food for the monks as the occasions called for and as we were able. I have not mentioned here the history of the origin of the above places and wondrous accounts of some of the special objects, as they are found in the biographies and histories and in Khyentsé’s Pilgrimage Guide.159

After crossing Gökar Pass we arrived back at our residence in Lhasa. That year I went to Ganden during the winter session and made offerings to Shartsé College, on which occasion I presented to Shartsé four pillar banners to be hung on the four front pillars of the assembly hall. The banners were made of brocade with dragon designs newly manufactured in China and were attached to gilded tsipar heads.

STAGES OF THE PATH TEACHINGS FROM KYABJÉ PHABONGKHA RINPOCHÉ

In my thirty-eighth year, the year of the earth-tiger (1938), I requested the sole refuge of all beings, including celestial beings, the great Phabongkha Vajradhara, to graciously consent to giving a discourse on the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path with the four annotations160 at Ganden Monastery that summer. Arriving at Ganden ahead of time, I made proper arrangements for his stay and set up a tent on Tsangthok, the green field at the foot of Ganden, for a reception ceremony in honor of my refuge and protector Vajradhara and his entourage.

Upon the arrival of the party to Tsangthok, I presented scarves and symbolic offerings of the holy body, speech, and mind to Lama Vajradhara and provided necessary services for the overnight stay. The next morning, when Kyabjé Vajradhara and his retinue arrived at Ganden, the incumbent abbot of Shartsé, Song Rinpoché Losang Tsöndrü, myself, and other incarnate lamas and monastic administrators, holding incense in our hands, led the procession from the spring, escorting Guru Vajradhara to his throne in the assembly hall of Dokhang House for an elaborate reception ceremony with stacked ceremonial cookies. After the attendants, the abbot of Shartsé, and others, including the monastic officials, had settled into the rows of seats, tea, ceremonial rice, cookies, and assorted dried fruit were offered. Following this, the officials of Shartsé and Dokhang House and I presented scarves and holy objects to Guru Vajradhara.

After the ceremony, Guru Vajradhara graciously came to stay at my residence above the assembly hall of Dokhang House, as had been arranged. The members of my labrang and I shifted quarters to the residence of the Dokhang House disciplinarian. We attended to any need of food and drink for Kyabjé Vajradhara and his attendants for a few days. Then until the conclusion of the discourse, for reasons of his health and diet, we supplied his personal attendants with staple foods, such as butter, barley flour, wheat flour, tea, and so forth, so that they did not need to purchase it from the market and offered the sums of cash needed to purchase fresh vegetables daily.

On the third day of the fifth month, an auspicious day of harmonious conjunction between the stars and the planets, the embodiment of all the victorious ones, precious guru of the beings of the three realms, entered the great assembly hall of Shartsé, Thösam Norbuling, to the tune of ceremonial music, preceded by incense holders, and placed his lotus feet on the teaching throne, the mandala of his magnificent face smiling — the sight of which was meaningful to behold.

The discourse was given to an assembly of two thousand disciples, including the incumbent and former abbots of Shartsé and Jangtsé colleges, tulkus, monastic administrators, and monks. In addition, in attendance were Drakri Rinpoché of Sera Jé, Sharpa Rinpoché of Sera Mé Kongpo House, Geshé Jampa Thayé of Sera Jé Tsawa House, who was the first great founder of the Dialectic Institute in Chamdo when it was newly established, and many other well-known holders of the Dharma, tulkus, and geshés from Sera, Drepung, Lhasa, and other places and hermits from various hermitages.

He began to deliver his discourse on the path pioneered by the vanguard Indian masters Nāgārjuna and Asaṅga, a synthesis of the essence of all the teachings of the victorious ones, the only path of fortunate beings, which possesses four preeminent qualities and three features that distinguish it above others, Jé Tsongkhapa’s Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path, Lamp of Three Worlds, with the four annotations and with experiential teachings that detailed the ways of putting his explanation into practice, drawn from Paṇchen Losang Yeshé’s Quick Path teaching on the stages of the path to enlightenment.

On the first day of the discourse, for reasons of auspiciousness, our precious guru recited three times the first few pages of the Great Treatise, following which I recited them once. I made offerings to the assembly that day. From that day on, in the beginning period of the teaching, two sessions were held daily from afternoon until dusk. In the later period of the teaching, nearing the summer session, it was necessary to hold an extra teaching session each morning. The precious guru taught without any sign of fatigue and with great pleasure and joy, upholding the deeds of compassion without the slightest reluctance. I made an offering of tea at the discourse once each day, except on occasions when others sponsored tea.

Before the discourse was completed, we suspended teachings on the fourteenth day of the sixth month in order to celebrate the sixty-first birthday of the synthesis of all refuges, our supreme guide and king of Dharma, Guru Vajradhara, with a long-life offering and the Halting the Ḍākinī’s Escort ritual161 made in conjunction with a tsok offering of the Guru Puja. We made these auspicious offerings so that the lama would endure for eons like an indestructible vajra. We extensively arranged thousands of the fivefold clouds of offerings.162

On the thirteenth we prepared for the ceremony for generating bodhicitta, and on the morning of the fourteenth, our guru graciously conferred upon us the bodhisattva vows in the manner of holding the aspiration and the engaging bodhicitta simultaneously, as is done in Śāntideva’s system. Thereafter, on the occasion of offering a long-life ceremony accompanied with a Guru Puja of the profound path, I made, without any miserliness, elaborate offerings of food and money to the assembly. In congruence with my ability and sense of devotion, I made physical offerings to the great Guru Vajradhara, poetically praised his supreme qualities, and offered up the entire universe symbolically with an elaborate description to request that his life remain steadfast to the ends of time. He eased my mind, saying that he was greatly pleased with the meaning of the verses describing the mandala and later requested a copy of my composition, which I provided.

The Dharma discourse continued the following day, lasting until the nineteenth, on which day, for the purpose of auspiciously closing the event, I presented a mandala with the representations of body, speech, and mind and a small honorarium, and offered tea and money to the assembly. As a fitting conclusion to the Dharma teaching, with quotes from scripture, such as “I have shown you the path to liberation, but you should know that liberation is in the palm of your hands,” the precious guru told those who had received the teachings that it was not enough to merely listen to them but that listening, contemplation, and meditation should be harmoniously employed in support of one another. Otherwise, if what one learns is not put into practice, then religious people run the risk of being possessed by demons, like celestial beings falling into devilish states. As in this verse from Essence of the Middle Way:

By the river of the speech

more powerful than sandalwood,

the fire of mental afflictions

tormenting beings is pacified.163

So did he exhort his disciples at length and in great detail, satisfying their hearts.

As the precious guru held Khangsar Rinpoché of Gomang and myself in highest regard among his disciples, he told the assembly by the way, “There is no doubt that their beneficial activities will expand and increase if they have long lives.” Dakpo Lama Rinpoché said, “The son will be greater than the father, the nephew greater than the son, and the cousin greater than the nephew. They will be as prophesied by Lama Rinpoché; therefore everyone should earnestly pray for them.” As mentioned above, many qualified lamas, tulkus, and geshés such as Drakri Rinpoché, who were quite capable of upholding and propagating the teachings, were sitting nearby. I felt quite shy about receiving such honor and praise amid such an assembly.

Afterward the precious guru spent a few days in leisure in between going to Wangkur Hill to make incense offerings and relax. Once, as we circumambulated the circuit path around Ganden, he confided in me his great pleasure at having had the opportunity to teach the stages of the path, the essence of Jé Tsongkhapa’s teachings, at his own seat of learning, which I took as a treasure of nectar to my ears.

On the morning of the day he left Ganden he placed upon my head the pandit hat that he had worn and presented me a copy of the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path, the first three pages of which were written in gold ink. Placing a bell and vajra in my hands, he gave me a set of silver victory and action vases filled with consecrated substances, a golden image of Tārā, a wooden teacup that Guru Vajradhara himself had used filled with precious stones of turquoise, coral, and so forth, and yellow brocade with the eight auspicious symbols. With regard to Dharma, he advised me to uphold, preserve, and propagate the sutra and tantra teachings of Mañjunātha Tsongkhapa, and I was very fortunate to have received much sincere advice from my guru.

At that time I thought that for someone such as myself, of little natural and acquired knowledge, deeply mired in unending distractions, and deprived of inner experience, it would be very difficult to find the means to serve the Dharma. Nevertheless, due to the wish of the guru and auspicious connections, I had to give many discourses, principally on the stages of the path, in the guise of the father-lama’s speech after the lama had passed into the state of peace. Having to give dry explanations without the confidence of any practice was like the maxim “the donkey measuring the hour of dawn in the absence of a rooster.” I interpreted the lama’s regard for me as an indication of my present role.

Thereafter, the great Guru Vajradhara was invited to Sang-ngak Monastery of Dechen to give a stages of the path discourse, and I accompanied him. An annual festival of the monastery and the town of Dechen coincided, and ritual dances were presented. I enjoyed the spectacle. There were no inauspicious omens or mishaps throughout the discourse; it was supremely successful, which I took to be a consequence of virtuous karma.

JOURNEY TO DUNGKAR MONASTERY, INDIA, AND NEPAL

From the time of the death of our manager Rikzin to this time of writing, Lhabu and I have assumed full responsibility for our labrang in a manner like a self-contained jewel. At that time, we retained Muli Losang Döndrup of Dokhang as an assistant manager. Later, since the labrang of Dungkar Monastery in Upper Dromo had repeatedly invited me and others to consecrate and present dhāraṇī prayers and relics to the stupa containing the embalmed body of Dromo Geshé Rinpoché Ngawang Kalsang, who had passed away the previous year, Lhabu, Phuntsok, Venerable Kalsang Wangyal of Namgyal Monastery, and I departed Lhasa in the tenth month. We crossed Gampa Pass, passing through Paldi, Nakartsé, Ralung, Gyantsé, and Phakri, finally arriving at Dungkar Monastery. There I interred the dhāraṇī in the stupa but postponed the consecration until after the New Year holiday.

Having come as far as Dromo, and seeing that it would be greatly meritorious if we made a pilgrimage to India and Nepal, we set out for Kalimpong on mules and horseback by way of Dzalep Pass, Rongling, and so on. We passed a few days in Dromo Labrang of Tharpa Chöling Monastery in Kalimpong. Then, with the assistance of an interpreter, we visited Bodhgaya, Vulture Peak, Nālandā, Kuśinagar, Śrāvastī, Varanasi, and Lumbini, and in Nepal the three stupas of Svayambunāth, Boudhanath, and Namo Buddha164 and other holy places. When we visited the stupa at Namo Buddha, we hired a taxi and rode up to the base of the hill. But on the return trip the taxi broke down, and we had to return on foot and so did not arrive at our quarters near the Bodhanāth stupa until eleven o’clock at night. It was quite a difficult trip. At each place of pilgrimage we made offerings to the best of our abilities in order to accumulate merit.

While I was staying at the Mahabodhi Guest House in Bodhgaya, a Ladakhi monk by the name of Ngawang Samten had made secret arrangements to buy a piece of property on which to construct a Tibetan temple and asked me to do the ground consecration. As the main stupa and the surrounding sites were under the administration of Jvaki Rāja, a Hindu, I discreetly performed the ground consecration on the site of the present Tibetan temple, Ganden Phelgyé Ling. On the fifteenth of the eleventh Tibetan month, during the late afternoon moonrise, I performed the ritual seeking permission from the field protectors and deities of the area to use the site and to request them to accept, protect, and bless the site in connection with the practice of Vajrabhairava. I also performed a ritual placing a small earth vase in the ground.

In order to offer gold paint to the Vajra Seat at the Mahābodhi Temple,165 Jvaki Rāja’s permission had to be sought, so I went to meet and present some gifts to him. He was sitting on a leopard skin that had a head and four paws. When I presented him with a ceremonial scarf, he gave me a hand blessing, placing his hand on my head. He was so pleased with me that he even provided me with an elephant and provided horses for my attendants when we went to the charnel ground at Sitavana. I had never traveled on an elephant before, and though it was pleasurable at first, it soon turned to misery, as the rough and jarring motion of the animal made me feel quite dizzy and nauseous.

I gave a brief discourse and an oral transmission of Tsongkhapa’s Praise to the Buddha, his Praise to Dependent Arising, the “three sets of prayers,”166 and others to a large number of Tibetan pilgrims in front of the Bodhi Tree. At the time India was still under British rule, and the country was not as developed as it is now. As there were no motor roads from railway junctions to the places of pilgrimage, it was necessary to travel either via horse and carriage or on foot.

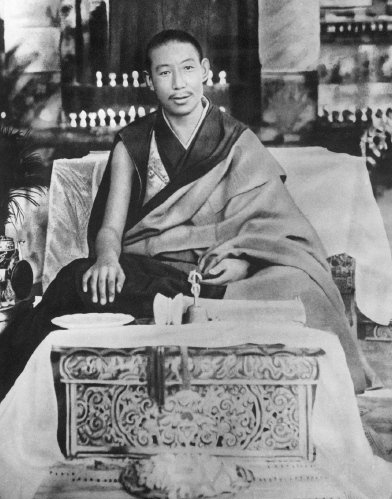

Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché giving teachings in front of the Bodhi Tree at Bodhgaya in 1938 during his pilgrimage to India

COURTESY OF PALDEN TSERING

After the pilgrimage we returned to Kalimpong, where in the open area in front of Tharpa Chöling Monastery, I granted initiation into the Great Compassionate One to a mixed crowd of over one thousand monks and laypeople as requested by a Tibetan social group. I also made short visits to Calcutta and Darjeeling to see and enjoy the benefits of those places. On the way to Darjeeling I took up an invitation to Ganden Chöling, the old monastery in Ghoom, and gave a short discourse there. In Darjeeling I gave a long-life initiation to a large number of people at the home of Lekden Babu, who had previously served His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama.

In my thirty-ninth year, I celebrated the New Year of the earth-rabbit (1939) at Tashi Chöling Monastery in Kurseong, Darjeeling. On the first day of the new year I composed a propitiation ritual for the local protector of Kurseong at the request of the patrons. We returned to Dungkar Monastery in Dromo via Kalimpong, Rongling, Dzalep Pass, and so on. I stayed there for three and a half months. After passing three days in performance of the elaborate consecration ritual for the memorial stupa, I spent fifteen days teaching a commentary on the Quick Path, along with a ceremony for generating bodhicitta, to a group of over two hundred monks and laypeople in the assembly hall of the monastery as requested by the monastic community and long-time patrons of the monastery, such as Phajo Dönyö of the Galingang Bönpotsang family. I gave initiations into Guhyasamāja, Vajrabhairava, five-deity Cakrasaṃvara in the tradition of Ghaṇṭāpāda, the Great Compassionate One, and permission to practice protector deities such as Mahākāla and Dharmarāja. I offered the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī and an experiential explanation of its generation and completion stages and gave a discourse on the Guru Puja.

We left Dromo and stayed at the house of Tsechö, a merchant chief from the Pangda family at Phakri. While there I visited the monasteries of Drakthok Gang, which the Gyütö Tantric College ran, Richung Potho Monastery, which was run by Ganden Shartsé, and the upper and lower monasteries of Tashi Lhunpo, spending one day at each monastery giving short discourses. In the courtyard of the Pangda home, I bestowed upon a large gathering an initiation into the Great Compassionate One according to the system of Bhikṣuṇī Lakṣmī. Then, for the benefit of my health, the merchant Tsechö arranged for me to spend two weeks at the Khambu hot springs in Phakri, where I met Ngaksur Ta Lama Rinpoché of Tashi Lhunpo, who had also gone there.

On the way back, I spent a day at a monastery called Khambu that had been established by Ngakchen Damchö Yarphel. Perusing some of the many texts there, I came across in one of the volumes a page containing a handwritten prophecy. Although I do not recall the exact words, it said in essence:

Avalokiteśvara will appear with the name of Thupa.

All his deeds and conduct will be equal to Rāhula’s.

Lightning will strike the minister Garwa.

And so on, concluding with:

In the year of the bird, every act will be complete.

When analyzed, it is clear that the text refers to the great dignity and bearing of the late Thirteenth Dalai Lama and to the punishment that befell Demo Rinpoché. The turmoil caused by the Chinese army during the water-rat year and His Holiness’s passing away for the benefit of others in the bird year were clearly predicted therein.

TO SAKYA, TASHI LHUNPO, AND BACK TO LHASA

Then we set out from Phakri to visit the sacred places in Tsang. Visiting a nunnery founded by Ra Dharma Sengé in a place called Tratsangdo, Dotra Monastery, Chilung, and so on along the way, we arrived at the glorious Sakya on the fifteenth day of the fifth month after crossing Drongdu Pass. That day, in the city quarters adjacent to the great temple at Sakya, mediums were performing trances in which local deities entered into them, just as they do in Lhasa during the universal incense-offering festival. Some of the mediums were through with trances and had joined the celebrants indulging in the drinking of beer. The Sakya township graciously made arrangements for me to stay in the house of a lay official and extended their hospitality to us, appointing an official, Mr. Maja, to be our liaison, giving us tsampa and providing food for our animals.

There were a variety of old handwritten texts in the room. Reading through them, I discovered some explanations of Logic and Epistemology, the Perfection of Wisdom, and Madhyamaka philosophy meant for recitation in the assembly hall by degree candidates, and collections of concluding auspicious verses recited by examination proctors. Except for minor differences in composition, style, and length, they were very similar to corresponding literature in the three great Geluk seats of learning and reminiscent of the style used by geshés at the Great Prayer Festival. It occurred to me that Jé Tsongkhapa and his disciples studied at Sakya, and that the tradition of the study of logic that existed at Sakya also became prevalent within our Geluk tradition.

As there were too many bedbugs in the room, I had to stay in a tent pitched on a green lawn by a stream. At that time, in order to meet with the incumbent of the Sakya throne, Dakchen Rinpoché of Phuntsok Phodrang, I had to follow his schedule and meet him during the daily morning tea ceremony. I went to his private chambers and paid my respects with prostrations. When I asked a few questions regarding the practices of the Thirteen Golden Dharmas of Sakya and the three cycles of red ones,167 he simply told me to consult the tutor to his two sons and did not impart any in-depth advice. I was given a large amount of relic pills, including a nectar pill. When I visited the temples in the surrounding complex, the tutor to his two sons was sent to act as my guide. At leisure, we visited the statue of Mañjuśrī with eyes that follow you, the far-resounding white conch of Dharma, and the Black Skin Mask Guardian in the Gorum protector chamber.168 I made extensive offerings and presented tea and money to the monks. The tutor and I had discussions over a variety of topics. He seemed well versed in studies concerning sutra but did not seem to have been too familiar with the Golden Dharmas or with the Path and Fruit (lam ’bras) oral instructions of Sakya.

From Sakya we visited the protector chapel of Palden Lhamo at Samling and Khau Drakzong, a pilgrimage site of Four-Faced Mahākāla. We crossed Atro Pass and visited the region of Charong, followed by visits along the way to Lhunpo Tsé Monastery, the great Maitreya statue at Trophu, and Gangchen Chöphel Monastery, arriving in the end at the illustrious Narthang Monastery. I visited most of the sacred images there. In one temple I saw one of the two replicas of the Bodhgaya temple finely crafted out of sandalwood during the era of Chomden Rikral (1227–1305). I found that the actual details of the stupa and the Bodhi Tree and such were exactly as they are now, which deepened my conviction in Bodhgaya as a sacred place. Though I really wanted to visit the hermitage of Jangchen and the temple at Shalu, they had to be put off due to lack of time.

When we arrived at the seat of Tashi Lhunpo in upper Tsang, a monastic official who would act as a guide was placed at our disposal by the administration of the monastery. They also provided us with large quantities of provisions and arranged accommodations for our party at Phendé Khangsar at the labrang of the tutor Lochen Rinpoché.169 At that time the supreme refuge Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara, endowed with great compassion that leads all beings to peace, was performing a reading and giving an explanation of the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to more than a thousand disciples at Dechen Phodrang palace at the special invitation of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. I had the good fortune of being able to touch my head to the dust of the feet of that kind, incomparable father lama and was buoyed by his expression of pleasure, like that of a father reunited with his son. Though the all-seeing Paṇchen Lama had not returned from China and Mongolia, in his absence I presented the symbolic universe and representations of the holy body, speech, and mind along with a ceremonial scarf and gifts as arrival and departure tributes during the tea ceremony sessions in accordance with ancient custom.

In the Kadam chamber of the palace of Gyaltsen Thönpo, Dzasak Lama Losang Rinchen of Kyapying sat before the seat of Paṇchen Rinpoché. I was seated in his presence, and tea, ceremonial rice, cookies, and a high stack of gifts of sacred relics, handmade clay votive statues, incense, and woolen material for an upper garment were presented to me. An inner room of the chambers had an exclusive protector chapel and a text of the Miraculous Book of Ganden.170 The room was blessed with the presence of a succession of Paṇchen Lamas, beginning with Paṇchen Losang Chögyen (1570–1662), As the room had become blessed by their great works for the benefit of the Buddhist teaching, with great joy and devotion, I made strong requests and offered dedicated prayers in connection with the seven-limb practice.

Then I visited the memorial stupas of the Paṇchen lineage, the statue of Maitreya, and most of the other temples. I made offerings to the various houses and amassed heaps of merit by offering tea and money to the monks in the assembly hall of Tashi Lhunpo. I also had the great fortune, in the presence of the official Kyapying Dzasak and the chief secretary, of viewing the sacred relics of Tashi Lhunpo in their relic box. One day I respectfully offered tea and money to the assembly of disciples at the discourse in Dechen Phodrang, and I presented the representations of the three holy objects and gifts to Guru Vajradhara. I attended one session of the discourse for reasons of auspiciousness, and I am deeply indebted to him for his kindness in sharing the nectar of his speech, which is ever meaningful.

While staying at Tashi Lhunpo, many of the disciples who were attending the discourse, including a large number of monks, came to see me, and I had to give readings and explanations of the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita and other works, one after the other, according to their requests. Lochen Rinpoché, the predecessor to the current incarnation, was then a young lama, and on his request I conferred the permission of Jé Rinpoché as the triple deity.

We departed Tashi Lhunpo and visited Panam Gadong Monastery and Pögang Institute at Gyantsé. At both these places we saw many of their sacred objects, such as a thangka of the Hevajra mandala that had belonged to Nāropa, garments of the great Kashmiri paṇḍita,171 and Sanskrit texts. I gave a long-life initiation to the local people at the invitation of Kashö estate of Kharkha. While staying at Serchok in Gyantsé, I made a leisurely visit to the sacred sites of Palkhor Chödé and gave a teaching on the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita at Shiné Monastery. Along the way I amassed merit by offering tea, money, and so on at Ralung Nunnery, Pökya Hermitage, and most of the other monasteries and sacred places.

Having traversed Kharöl Pass, Nakartsé, and so on, we crossed the Tsangpo River at Nyasok and spent one night at Nyethang.172 There we visited and paid respects to the Tārā temple, wherein the principal statue was the “Tārā who spoke,” and saw the stupa that Lord Atiśa had carried with him at all times.

We arrived back in Lhasa at the end of the sixth month. That fall, the supreme Phabongkha Vajradhara, having come to the tantric college of Sera Monastery, taught Aśvaghoṣa’s Fifty Verses on Guru Devotion and bestowed an initiation into Akṣobhyavajra Guhyasamāja. When he conferred initiation into Vajrapāṇi Mahācakra at Hardong House of Sera Jé, I too received a flood of initiation blessings into the core of my heart.

The great fourteenth incarnation, our supreme refuge and protector of the land of snows, the Noble Holder of the White Lotus who has manifested in the play of benefitting all beings, was in procession from Amdo, and on the occasion of his lotus feet gracing the ground of the capital city, Lhasa, at the end of the eighth month (early October 1939), I joined the tulkus of Sera, Drepung, and Ganden in a grand government reception on the plain of Gangtö Dögu. Seeing the mandala of his face endowed with the major and minor marks of enlightenment while paying respects to him, I attained the nectar that leads to liberation.

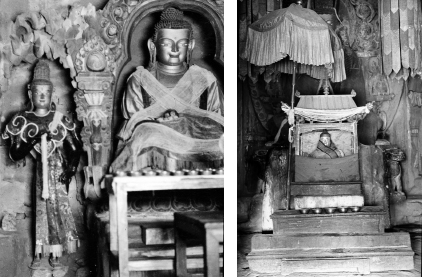

The Nyethang statues of Tārā and Śākyamuni (left) and Atiśa (right), 1950

© HUGH RICHARDSON, PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD; 2001.59.2.70.1 AND 2001.59.13.64.1

RECEIVING AND GIVING FURTHER TEACHINGS

In the spring of my fortieth year, the year of the iron-dragon (1940), I received the following initiations at the feet of the all-embracing lord of a hundred buddha families, the tutor Takdrak Vajradhara, at the Norbulingka: five-deity Vimaloṣṇīṣa, five-deity Viśuddhaprabhā, Amitāyus in the system of Machik Drupgyal, many peaceful and wrathful deities, the nine white deities, and Gongkhukma of Rechung. And at the feet of the supreme refuge, Ling Rinpoché Vajradhara, I also received instruction on Ocean of Attainments of the Generation Stage of Guhyasamāja.173 In the rainy-season session I went to Ganden, where at the request of Phara Tulku of Ganden Jangtsé, I gave an experiential discourse on the Guru Puja and mahāmudrā to an audience of former and current abbots of Jangtsé and Shartsé colleges, tulkus, and monks, more than five hundred in number, in the Phara House assembly hall.

One day during the following winter, my root guru, Phabongkha Vajradhara, sent a message to Lhasa via his attendant Namdak-la that he was going to give a detailed discourse on the generation and completion stages of Cittamaṇi Tārā, that it would be best if I came as such teachings would be difficult to receive later, and that I could stay at the retreat residence of his labrang. I left for Tashi Chöling Hermitage immediately, where I received instructions on the root text of the sādhanas of Cittamaṇi Tārā, which is a divine vision of Takphu Vajradhara, with detailed instruction on both the generation and completion stages, associated activities, and the rite for bringing rain based on commentarial texts on generation and completion composed by that lama.

At the conclusion of the teachings, I received oral instructions on the complete ritual practices related to Shukden, and saying “For the sake of auspiciousness,” he gave me transmission of oral advice with detailed teachings on the methods for gaining longevity through reliance on vajra recitation of wind in connection with the longevity deity White Heruka. As I mentioned above, had Guru Vajradhara not called me for these profound teachings, I would have been deprived of them because I was involved in prayer services in Lhasa. The kindness shown to me by the father lama in holding me with his rope of compassion is as weighty as the mass of Mount Meru.

The previous year, Kyabjé Vajradhara had started having ominous dreams, and his tense looks indicated that he wished to depart to another place. So as soon as his teaching concluded, we senior incarnate lamas, including Ling Rinpoché, Demo Rinpoché, Drakri Rinpoché, Sharpa Rinpoché, and others, discussed among ourselves the idea of asking him to accept a long-life offering. Once it was settled, an elaborate long-life offering of White Heruka with ritual invocation and banishment of ḍākinī escorts was made together with all the lamas, geshés, and resident monks of the Tashi Chöling Hermitage in its assembly hall. Conjoined with the offering were our requests that his body, speech, and mind remain steadfast like an indestructible vajra throughout existence, glowing with the light of the blessings of benefit and joy, like the great life-sustaining vitality that preserves the precious Dharma in general and in its particulars. He replied to our prayer, saying, “Whatever obstacles there may have been must certainly vanish due to the ḍākinī long-life offering made by this assembly of many of my great disciples,” and that Vajradhara himself will consider this to be the case. His good reply seems to have been interpretable, with the motive to soothe our minds.

On the morning of the first day of the first month of my forty-first year, the year of the iron-snake (1941), I recited upon invitation the mandala description and offered the eight auspicious symbols and substances as well as reciting inaugural words of truth at the private ceremony for the inauguration as regent of Tutor Takdrak Vajradhara. This took place at his Lhasa residence, Kunsang Phodrang, prior to the actual ceremony of investiture to the seat of regency in the Potala Palace in place of Regent Radreng Rinpoché, who had resigned as regent in the twelfth month of the previous year. I performed my duties at the ceremony satisfactorily.

That year Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara made offerings to the assembly at the Great Prayer Festival. I, too, made offerings, and coincidentally we both had an audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama on the same day to present him his share of offerings. I was supposed to sit to the front of Guru Vajradhara according to the hierarchy of my rank as Tsokchen Tulku, but I attempted to move to a seat behind him. However, Vajradhara told me to sit where I was because there are always exceptions to the rule, and so I sat there feeling very uncomfortable and nervous throughout the ceremony.

When the Great Prayer Festival concluded, I thought, “It is not right that on the tenth of each month an imagined image of guru Cakrasaṃvara is my object of worship when the real guru is physically here near me, working for the benefit of sentient beings. It will be more meaningful to make offerings to the root guru who is the embodiment of all refuges, whose presence represents the mandala of the vajra body, with all the bodily elements complete in the nature of ḍākas and ḍākinīs, who is someone to whom the offerings can actually be made and by whom they can actually be consumed.” So on the twenty-fifth of the first month, I invited my only source of hope and refuge, Guru Vajradhara, and his retinue to my house for a feast in order to accumulate merit. With great pleasure, he stayed in leisure, satisfying the party, which relished myriad sublime flavors of nectar speech that radiated forth as the holy Dharma, each part of every word being noble in meaning. At one point he commented that “If His Holiness the present Dalai Lama encounters no obstacle to his life, he will rival Kalsang Gyatso, the Great Seventh Dalai Lama. Should you be called upon to serve him, you must serve him to the best of your ability.” This seems to have been spoken as a prophecy, given that I later was called upon to serve him as an assistant tutor and then tutor, a service that I have continued to perform these many long years.

Regent Takdrak Vajradhara, Lhasa, November 9, 1950

GETTY IMAGES

As Lady Yangzom Tsering of Lhalu Gatsal household had a long-standing request for Kyabjé Vajradhara to install outer, inner, and secret statues and the thread-cross abode of Shukden in their protector chapel, Vajradhara instructed me to make ready arrangements for installation of the thread cross. So I gathered the necessary items in advance and completed the preparations. That year, just after the Great Prayer Festival, Kyabjé Vajradhara, along with eight monks from Tashi Chöling and myself as assistant, performed elaborate rituals at Lhalu Gatsal for three days. On that occasion, I received the life entrustment for Shukden together with Finance Minister Lhalu Gyurmé Tsewang Dorjé and his wife.

On the eve of Guru Vajradhara’s departure from Lhalu to bestow teachings on the stages of the path at Dakpo Shedrup Ling by way of Chaksam Tsechu, I offered him my brocade monk’s robe embroidered with a flower design motif, strung with a net of small pearls, and a ceremonial scarf together with mandala offering. These offerings were made primarily for him to live a long life as a protector of the teachings and all beings, such as myself, and also to offer thanks to him in advance for the composition of Shukden thread-cross rituals of providing a base, satisfying, and repelling, as well as rituals of the same protector on the torma of expelling, fire offering, and increasing wealth. He said that this would be difficult for him to do and that based on my understanding and notes, I should compile the texts. He gave me instructions on how to compose the texts, telling me to compile the ritual with the necessary supplements from other relevant ritual sources. In essence, he said that it was up to me to complete his work regarding this protector of Dharma, and therefore he was charging me with that responsibility. My thought at the time was that he was telling me this because he had little time for the work himself due to his busy schedule. Little did I realize that he was conveying to me his implicit wish that I finish his life’s work. It was just as when, though the Buddha said that, if requested three times, “Tathāgatas, if they so wish, can remain for eons and eons,” Ānanda, obscured by evil influences, failed to request him to stay. How I regret not asking him to live longer.

APPOINTMENT AS ASSISTANT TUTOR AND THE PASSING OF PHABONGKHA RINPOCHÉ

The very next day I received a summons from the office of the Norbulingka Palace saying that Trijang Tulku and Sera Mé Gyalrong Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso should come to the palace. When we arrived we were told through the lord chamberlain that the precious regent had appointed me an assistant tutor in place of Ling Rinpoché, who had been promoted to the position of tutor to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and that Sera Mé Gyalrong Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso would assume the role of adjunct tutor. And that given these changes in title, from that time on it would be appropriate for Trijang Tulku to sit at the head of the row of senior monastic officials of the government, as had Ling Rinpoché before him, and for Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso to sit among the ranks of adjunct tutors, in order of seniority.

On an auspicious day, I appeared for an audience before His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the regent. Subsequently, on the fifteenth day of the fourth month, during the daily morning tea session in the sunlight room of the Norbulingka Palace, Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso and I presented to His Holiness and the regent silk scarves and offerings of the holy body, speech, and mind and other gifts, along with token offerings of funds for rice and tea. Following the audience, we sat in our designated seats for the tea session. That day I received well-wishers who came to offer their congratulations. Every day thereafter I fulfilled my obligation to attend the daily tea sessions and special government functions, just as all government officials must.

After several days had passed, at the behest of the precious regent, I was asked to instruct His Holiness in reading cursive and printed letters and to train him in memorization of daily prayers and religious recitations, on account of the increasing official duties of the precious regent, and to also do so whenever Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché was unavailable. On an auspicious day, with a ceremonial scarf and ritual offerings of the holy body, speech, and mind in hand, I bowed at the feet of His Holiness and began his lesson with an auspicious verse. From then on I came to serve him whenever there was time in the morning and sometimes in the evening between visits from the two tutors. I shifted my permanent residence to a room in the assistant tutors’ quarters.