TRAVELS TO KUNDELING AND TÖLUNG

IN THE FOURTH MONTH of my forty-fourth year, the year of the wood-monkey (1944), I gave teachings on the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to over one thousand disciples in the assembly hall of Kundeling Monastery for one month at the request of Kundeling Tatsak Hothokthu Rinpoché.

In the summer Minister Taiji Shenkha Gyurmé Sönam Topgyé requested me to give initiations into Guhyasamaja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava for the benefit of his late son, Dechen Gawai Wangchuk. I gave the initiations to about three thousand disciples for five days in the assembly hall of Meru Monastery in Lhasa.

In the eighth month, I went to the hot springs in Tölung for the sake of my health. At that time, the monks of the Gyümé Tantric College happened to be observing the late summer retreat in the nearby Chumik Valley, so at the invitation of the abbots and administrators of the monastery, I stopped by the monastery along the way. I offered the monks a reading transmission of two of the three textbooks on the five stages of Guhyasamāja that are unique to Gyümé. These three are renowned as the Three Stones Passed from Hand to Hand.181 I presented the assembly with many donations.

I spent two weeks at the hot springs, where I met some people from Tölung Rakor, the birthplace of my predecessor, and I gave them some small gifts.

Soon after my return from Tölung, at the request of Mrs. Tsering Drölkar of the Bayer family, who were staying in the Mentö household, over the course of just a month I gave personal instructions on the Quick Path in connection with the Words of Mañjuśrī, along with offerings and the ceremony for generating bodhicitta to a gathering of around twenty-seven hundred in the assembly hall of Lhasa’s Shidé Monastery. The assembly was comprised of tulkus and geshés from the three monastic seats, their students, and monks from the Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges as well as retreat centers.

I sent four large pillar banners of multicolored brocade appliqué in the takshun design, with large dragons, accompanied with appliqué forms of tsipar heads to be hung on the four tall pillars in the assembly hall of my monastery in Chatreng and sent a complete set of the Kangyur along with covers to Dongsum Riknga House.

A DISPUTE BREAKS OUT

If one does not avert pride in one’s reputation, attire, pedigree, and status, it is difficult for a river to flow upward on a hill of arrogance unless one seeks out advice and teachings from the wise.

That winter, having invited a teacher from Lhasa’s Astro-Medical Institute — a monk named Palden Gyaltsen who hailed from Yangpachen in Tölung — to my residential quarters above the Potala’s school of administration, I, together with Dzemé Tulku of Ganden Shartsé, requested instruction on both Anubhūti’s Sarasvatī Grammar Treatise (Sarasvatīvyākaraṇa) and its commentary Hundred Rays of Light by Getsé Paṇḍita Gyurmé Tsewang Chokdrup, up to the section on the five types of sandhi. We also studied the root text Ratnākara’s Prosody (Chandoratnākara), written by the pandit Ratnākaraśānti, and its commentaries by Minling Lochen and Lama Lhaksam, up to picture prosody (citrakavya).182 We were unable to fully complete the picture prosody portion due to the proliferation of distractions beyond our control.

In the tenth month of that year, fighting broke out in connection with barley debt due to a disagreement between the steward of senior secretary Chöphel Thupten’s Lhundrup Dzong estate in Phenpo and Sera Jé’s debt collectors, and the steward died. The senior secretary filed a report of the incident with the regent, a commission of six monastic and lay officials was appointed, and having summoned the chief culprit, details began to emerge. The investigation of this incident took place around the time of the Great Prayer Festival in Lhasa of the wood-bird year (1945), during which Tsemönling Hothokthu had invited His Holiness to preside over the assembly, as this was also the time of Tsemönling’s offering for his geshé examination. There was an incident when the abbots and monks of Sera’s Jé and tantric colleges boycotted the sessions for three days during the festival. An official order setting out the grave consequences of their actions of contempt was issued by the ecclesiastical offices at the Potala. Only then was the festival barely held as usual.

At the completion of the Prayer Festival and Subsequent Prayer Session, when the investigation concluded, the abbots of Jé and Ngakpa colleges were expelled along with a few of the administrators and debt collectors, who were exiled to confinement in faraway districts. On account of this, many of the monks of Jé and Ngakpa colleges badmouthed the precious regent and accrued heavy karma due to the actions of a few bad individuals. In addition, because of the expulsion of some officials who were close to Radreng Rinpoché, it was a time when bonds between guru and disciple were broken. I disliked all these events very much and gave very frank and honest advice in order to prevent further hardship for Regent Takdrak’s treasurer, Tenpa Tharchin, but I could not stop it. As Sakya Paṇḍita says in his Jewel Treasury of Wise Sayings:

However you may try to reverse a waterfall,

you must accept that it only flows downward.183

THE RITUAL TO TRANSFER LHAMO’S SHRINE AT DREPUNG

In my forty-fifth year, the year of the wood-bird (1945), the government performed extensive restoration of the Ganden Phodrang Palace at Drepung Monastery. When the preparations for the demolition of the rooms on the upper floor of the western complex of the palace were ready, the protector house of the sealed statue of Gotra Lhamo (Raktamukha Devī), which is kept in a chamber of the palace, had to be moved temporarily. The precious regent told me that this protector is known to be very strict in her commands. Anyone who took even a mere scarf offered to the statue experienced immediate negative consequences. Therefore I was entrusted to oversee the proper ritual performance for the removal of the statue during the renovation phase.

After the Subsequent Prayer Session in Lhasa, I left for Drepung with the presiding master and chant master of Namgyal Monastery as ritual assistants and made propitiatory offerings to Palden Lhamo for a few days. The night before moving the chamber I dreamed I was in a huge assembly hall filled with thread-cross effigies and many large old and new torma cakes. It was so full of heaps of various things that I could find no place to step. As I looked for a path, a young lady came and, moving with a pleasing gait, showed me the way. I took this dream as a sign that the goddess was pleased and that it was time to move the protector chapel.

The next morning during the actual transfer, we opened the protector chamber in the presence of the monk-official secretary who was representing His Holiness. At first the others hesitated to touch the sacred objects and would not move them. Although I lack confidence in the view of emptiness and any meditative insight, since I had done the approaching retreat of Palden Lhamo, maintaining confidence in my being a meditational deity and in the dream I had had the previous night, I took a few objects and some scarves and moved them to the sunlight room of the palace, all the while reciting the mantra of Palden Lhamo.

Afterward, everyone — the presiding and chant masters of Namgyal Monastery (my ritual assistants), the overseer of construction and his staff, as well as the representative of His Holiness — moved the various objects, such as taxidermied animals, that had accumulated in large quantities over the years. This took three days. We then moved the main image of Palden Lhamo, which was the size of a man and was made of silver, with a representation of the sea of blood and included her mule mount and the background fire, measuring one story in height. The two attendants, one with the face of a lion and the other with the face of a makara sea monster, were each the size of an eight-year-old child. As the statues had originally been made individually, it did not end up being difficult to move them.

Once we had separated the main body of the statue from the sea of blood and the mule, the statue was invited to one of the rooms in the eastern wing of the palace. During the transfer I had the Namgyal monks do the elaborate invocation of Palden Lhamo, with melodious chanting together with ritual music. I along with the overseer of the restoration, the senior secretary Ngawang Söpa, and the representative of His Holiness led the procession with incense in our hands. The senior tulkus and some of the older geshés from the four colleges of Drepung carried the statue. After assembling the statue, we made a ritual of mending and restoration before the statue with extensive propitiatory and tsok offerings.

We pried open a large box containing various thangka scroll paintings that had been in the protector chapel. Inside we discovered an extremely old painting of Vajrabhairava with stacked heads that had been the personal devotional meditation object of Ra Lotsāwa and was in keeping with the Ra Lotsāwa Collection on Vajrabhairava: Oral Transmission of the Ḍākinīs.184 There was also a copy of a similar thangka that the Fifth Dalai Lama had commissioned from Sur Ngakchang Trinlé Namgyal (these being both the original and its copy) and a painting of the Guardian of the Tent in standing position that was the personal meditational object of Drogön Chögyal Phakpa.185 There were many wonderful historical paintings, including a thangka of Rishi Viṣnu hand painted by Surchen Chöying Rangdrol.186 Moreover, there were several thangka images of Four-Faced Mahākāla and the Tent Guardian that were the personal meditation objects of some of the prior Sakya patriarchs.

In one of the cabinets for ritual cake offerings, there were some requests to the protectors written in the hand of His Holiness Tsangyang Gyatso187 and replies to a few of the questions that he presented to the protector Lamo Tsangpa on various political matters. It also contained several rolls of flowery letters written to intimate friends in the manner of tantric conduct. His handwriting was of fair quality, but the verses he composed were excellent.

At the same time as the palace at Drepung was being restored, the palace of His Holiness at Gephel Hermitage was also to be restored. So I went to that monastery one day and did the rituals for the transfer of those deities and nāgas and the consecration ritual for construction. During these not even one among our staff, myself included, suffered any serious mishap, and I credit this success to the divine protection of the Three Jewels and the goddess protector.

Later, when the restoration of the palace at Drepung was complete, I went there with the ritual assistants of Namgyal Monastery, and we moved the statues, including that of Palden Lhamo, and the sacred objects back to the protector chapel in the renovated palace and made extensive propitiating offerings accompanied by tsok offerings over the course of seven days. Previously there had been no thread-cross abode of Palden Lhamo in the protector chamber, but as a new one had been commanded, we constructed a complete, elegant thread-cross and performed an extensive ritual for it.

That summer, in fulfillment of a request by Kusho Tserap of Namgyal Monastery, with the aim of sowing roots of virtue for his late mother Palkyi, I taught the Quick Path and the Words of Mañjuśrī in association with its experiential commentary to an audience of more than a thousand, including the entire assembly of Namgyal Monastery, in the Jaraklingka park, where the monks of Namgyal Monastery spend their annual picnic at the conclusion of the rainy-season retreats. At the end, on the day of the ceremony for generating bodhicitta, the Dharma protector of Lhasa’s Darpo Ling, Lord Chingkar, inhabiting his medium proclaimed, “Your recent discourse on the stages of the path was excellent!” He also advised the administrators of Namgyal Monastery, saying, “Beginning next year, the general assembly of Namgyal Monastery must take up the task of requesting teaching on the stages of the path and on the commentaries to the generation and completion stages of Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava in turn every year, without break.”

That year, at the beginning of autumn, as requested by the previously mentioned Mrs. Tsering Drölkar of the Bayer family, at Lhasa’s Shidé Monastery I extensively taught the profound path of Guru Puja and mahāmudrā combined, with its associated profound commentary, to more than two thousand monks from Sera, Drepung, and the Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges who had previously received initiation into the deities Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava.

A NEW APPOINTMENT

In the winter, the precious regent appointed Gyatso Ling Tulku of Gungru House of Gomang College as assistant tutor with the rank of senior ecclesiastical secretary,188 and I was promoted to the rank of Darhan, which required me to sit before officials with ranks of Dzasak, Ta Lama, and Taiji.189 On the occasion of my advancement to the new position of Darhan, I made offerings to His Holiness and the regent in accordance with ancient tradition.

In my forty-sixth year, the year of the fire-dog (1946), during the Great Prayer Festival, I invoked the divine presence of the Nechung protector through his medium in a trance at the temple in old Meru Monastery. The Nechung oracle gave me a scarf with the representations of the body, speech, and mind and expressed great pleasure and appreciation for the discourses I had been giving. He said that it was great that I was propagating the profound and the vast nectar-like teachings of the incomparable leader and son of Śuddhodana (i.e., Buddha Śākyamuni) at such a crucial time.

His Holiness was to commence his dialectical studies at Drepung in accordance with tradition, but a private rehearsal ceremony was held in the Ganden Yangtsé chamber of the Potala Palace. This was presided over by His Holiness in the center, with Regent Takdrak Rinpoché, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, myself, Gyatso Ling, and Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso of Sera Mé sitting in rows to the right and left. Everyone recited Praise to the Buddha and Chanting the Names of Mañjuśrī.

Because Gyatso Ling and Geshé Khyenrap Gyatso recited the texts at such disparate pitches, one high the other low, Ling Rinpoché burst into laughter. This made His Holiness laugh, and I also began to laugh uncontrollably, and the recitation was nearly interrupted. Though Regent Rinpoché wore a serious expression on his face, I could not stop laughing, even out of fear. Others present, including the chief abbot, his chief attendant, his assistant, the ritual assistant, and the lord chamberlain, all also laughed uncontrollably, like the maxim “one laughs if you look at someone else laughing.” I later took this to be a sign His Holiness would attain the pinnacle of scholarly studies.

From that day forward, every day, in turn, we three serving scholars presided over His Holiness’s dialectical study each afternoon, with the exception of break periods during special and scheduled government ceremonies. We were also permitted leaves of absence in exceptional cases to give teachings.

Regarding the reincarnation of my sole father in unrivaled kindness, the great Phabongkha Vajradhara: as the visions of Nakshö Takphu Rinpoché, the predictions of the Panglung Gyalchen and Gadong oracles, and my own repeated divinations were found to be in agreement, the young reincarnation, who had taken rebirth at Drigung in upper Ü, was brought to Tashi Chöling Monastery at the beginning of the second month and formally placed upon the throne of his lofty predecessor. I was present on that occasion and attended the ceremony and made offerings.

At the beginning of the third month, at the request of a group of newly ordained monks of Gyümé Tantric College, I offered initiations into Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava along with their preparatory rites, and explanation and transmission of Aśvaghoṣa’s Fifty Verses on Guru Devotion, for five days to a large number of monks, primarily from Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges, in the Gyümé assembly hall. At the command of Regent Takdrak Vajradhara, I compiled and edited the recitation texts of the three observances of the Vinaya monastic rules of discipline and other sutra and tantra texts recited by the monks of Takdrak Hermitage. In particular I compiled the ritual chant of the elaborate consecration, Causing the Rain of Goodness to Fall, in accordance with the tradition of the Gyümé Tantric College and the self- and front-generations, the consecration of the vase, and initiation and fire-offering rituals of Guhyasamāja Lokeśvara.

Likewise, the monks of Gyümé Tantric College had requested that the precious regent recompile their manual for subjugating demons based on the Dharmarāja rite composed by Drakar Ngakrampa,190 since there were various readings, notes, and emendations on handwritten copies that were more reliable. Since he had no free time, he told me to do it. I therefore examined all the relevant materials, particularly chapters of Drakar Ngakram’s own commentary, and compiled a reliable chanting ritual for subjugating demons called A Yantra Wall of Vajra Mountains.191

In early summer, to sow seeds of virtue on behalf of lay practitioner Tsewang Norbu at the request of Mrs. Lhamo Tsering, who lived below the meat market in Lhasa, I gave a discourse on the Quick Path for twenty-five days to over three thousand. This discourse was given under a large canopy in the Jarak picnic grounds of Namgyal Monastery. Following that, at the request of Namgyal Monastery, I gave discourses for fifteen days on the two stages of thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava to over one thousand disciples who had received the Vajrabhairava initiation and an explanation of the construction of the three-dimensional mandala. Scattered throughout the discourse, I gave explanations on the visualization of the fire-offering ritual, the sixty-four-part torma offering, and the great torma ritual and their different traditions and methods. I explained these as thoroughly as I myself had learned them from oral teachings without concealing anything.

Although Namgyal Monastery preserved excellent traditions of the sand and cloth mandalas for Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava, they did not have a tradition of instruction for the creation of three-dimensional mandalas. Therefore, in consultation with His Holiness’s chief ritual assistant, Losang Samten, and the presiding master, Tenpa Dargyé, I immediately began fresh instruction on the construction of the three-dimensional mandala. I appointed Ngakrampa Tsultrim Dargyé of Trehor House of Gyümé Tantric College as the principal instructor. Eight Namgyal monks, including the ritual master and the chant master, received thorough training, and the new mandala that they constructed as a result of their training was excellent.

ILLNESS AND SCHISM

I was sick for twenty days during the sixth month of that year with a serious intestinal fever, after which I was very ill with edema. Though I was on the verge of death, I recovered under the treatment of doctor Khyenrap Norbu, senior chair and director of the Tibetan government’s Astro-Medical Institute, who was a master equal to the great Yuthok, the king of medicine,192 and the treatment of His Holiness’s personal physician, Khenchung Thupten Lhundrup. My recovery was helped by many religious rituals and the care that I took, but I was still barely able to go outside by the ninth month.

That winter at the request of Chözé Ngawang Dorjé of Trehor Shitsé Gyapöntsang, who was a prominent student at Sera Jé Monastery, and his brother Döndrup Namgyal, I began giving a discourse on the Easy Path to a group of about fifty people. Initially I held the discourse in my quarters in the Norbulingka summer palace until one day the lord chamberlain, Khenchung Thupten Lekmön, came to visit me and said: “Teaching the stages of the path to them like that here in the Norbulingka is like locking the door after letting a thief in! It would be better if you stopped for the time being.”193 I therefore moved to my residence in Lhasa and continued to teach there to about one hundred disciples. Since the protector and lord, the precious regent, could have had no such prejudice, as he is a great person, it seems that this must have been due to the lord chamberlain’s own small and narrow-minded assumption, causing him to mistake his own shadow for a spirit.

The former regent Radreng Rinpoché and the incumbent regent Takdrak Rinpoché were undisputedly great beings with the highest attainments of abandonment and insight. But buddhas and bodhisattvas appear according to the dispositions of their disciples, in whatever illusory guise will best tame them — demons and devils, the pure and the impure, tamers and those to be tamed.

In my forty-seventh year, the fire-pig year (1947), Radreng Rinpoché and Takdrak Rinpoché could have no peace with one another on account of the many false rumors of dissension and the provocations of attendants. For Takdrak Rinpoché there was Treasurer Tenpa Tharchin, Chamberlain Thupten Lekmön, and Chairman Ngawang Namgyal. Among Radreng Rinpoché’s subordinates, there was his brother the Dzasak, Nyungné Tulku of Shidé, and Khardo Tulku of Sera Jé. As Sakya Paṇḍita’s Jewel Treasury of Wise Sayings (5.34) says:

A person who constantly strives for dissension

will sever even the firmest of friends.

If water flows continually,

won’t even rocks split apart?

It became apparent that the supporters of Radreng Rinpoché were plotting to harm Regent Takdrak Rinpoché, which was the first step toward their own demise. So, as soon as the meeting between the regent and his cabinet adjourned, the ministers Surkhang Wangchen Gelek and Lhalu Tsewang Dorjé were dispatched to Radreng Monastery together with a contingent of soldiers and leaders of the Drashi army base to arrest the former regent. They were dispatched suddenly in the night of the twenty-third of the second month.

I did not hear of this news until noon the next day. At that time, I was living at my residence in Lhasa and the cabinet minister Rampa Thupten Kunkhyen sent a secret message to me saying that I had better go to the Potala right away. He also said that as he needed to stay at the Potala for a few days, he would like to stay in my quarters there. I left for the Potala immediately.

Late that afternoon, at the order of the Tibetan cabinet, the Radreng labrang and the Yapshi Phunkhang mansion were sealed and locked up. The former and incumbent Dzasak of Radreng and the retired minister Gung Tashi Dorjé of Phunkhang, along with his son, were summoned to the Potala, where, stripped of rank and title, they were imprisoned in Sharchen Chok, the Great Eastern Tower prison at the Potala. The following day, the homes of Radreng Labrang’s supporters — Khardo Tulku, Nyungné Tulku of Shidé, and the Sadutshang family of Trehor — were locked up, and Khardo and Gyurmé Sadutshang were also imprisoned in Sharchen Chok. Nyungné Lama escaped when arrest was imminent and shot himself.

On the twenty-seventh day of the second month, having been brought over Gola Pass of Phenpo and across the Tsesum plain at the foot of Sera, circled clockwise around the Potala, and in through the eastern gate of Shöl, Radreng Rinpoché was interned in Sharchen Chok, where he remained under heavy guard. Later Radreng Rinpoché was taken for interrogation at the meeting of the National Assembly. From my quarters at the Potala, I saw him taken back and forth through the entrance with the three staircases at Deyangshar Courtyard under tight security. It made me distraught to see such a great lama and leader who previously traveled amid a host of private and government officials in great glory and pomp now living in a dark prison cell without even one attendant, surrounded by soldiers, and having every day to go for interrogation at the National Assembly. I sensed how troubled he must have felt, but there was nothing that I could do.

I heard that Radreng Rinpoché died in prison on the night of the seventeenth of the third month. The inquiry into his case had concluded the previous day, but those attending the meeting disagreed as to his sentence. It isn’t clear whether Rinpoché died of his own will in anticipation of a serious punishment or whether there were other unexpected ill circumstances. Later many rumors circulated that he was killed secretly by the leaders of the prison guards. Radreng Rinpoché’s brother the Dzasak and Khardo Tulku were kept under arrest in the new prison with two rings of security in the bodyguard unit at the Norbulingka. The two of them were imprisoned for life with manacles, fetters, and wooden yokes around their necks. All the others involved were also given heavy sentences by the National Assembly. Since ex-minister Phunkhang and his son, as well as Gyurmé Sadutshang, had close connections with the Radreng labrang, they were initially suspected and kept under arrest. But later, as it became evident that they had no involvement in the intrigue, their wealth and property were returned, and they were allowed to live in peace.194

At that time most of the monks of Sera Jé, including Tsenya Tulku, were conspiring to rise against the government. The monastic officials had no influence in the matter, and there was much unrest. The government sent the cabinet minister Kashöpa Chögyal Nyima, General Dzasak Kalsang Tsultrim, monk-secretary Ngawang Namgyal, the finance minister Ngaphö Ngawang Jikmé, and Namling Paljor Jikmé to the Drashi military encampment, and with armed battalions they marched to Sera Jé and made a show of force. The monks of Sera surrendered, and the conflict was prevented from spreading further.

At Radreng Monastery, attendants of the Radreng labrang killed seventeen soldiers that were guarding the property. General Kalsang Tsultrim and Shakhapa Losal Döndrup, governor of the northern region, were therefore dispatched to Radreng with a large contingent of soldiers. They shelled the seat of Radreng and caused serious damage to the temples, images, and religious objects. Soldiers looted the property of Radreng Labrang, which was comparable to the treasury of Jambhala, god of wealth, and the government confiscated the rest, leaving nothing behind.

Reflecting that the joys and sorrows of samsara are unstable, changing in an instant, like a flicker of lightning, I was deeply moved to renounce forcefully all the meaningless activities of this life and withdraw into the mountains like a wounded deer, to live in the manner of āryas with the four qualities.195 I could see the need to wholeheartedly dedicate my body, speech, and mind to practice, but because of the firm grip of my attraction to this life, I was not able to sever myself from the allure of distracting activities.

Due to the incidents related above, various prejudiced rumors regarding the precious regent and Radreng Rinpoché were spread by many from both factions. However, there is no certainty with regard to the ordinary perceptions of disciples and the power of their karma. As with what befell the ārya Maudgalyāyana, the arhat Udāyin, and the great king Ralpachen, it is best not to see faults in this situation and to withhold judgment.196 As the “Friendship” chapter says:

If those who have done no wrong

associate with those who have committed evil,

they arouse suspicion of having done wrong,

and a bad reputation will accrue.

Those who associate with those they ought not to

themselves become tainted by the others’ faults.

An arrow, put in a quiver tainted with poison,

though not stained with poison will become so.197

Mañjunātha Sakya Paṇḍita stated:

Noble beings acquire bad habits

when they befriend the wicked.

The sweet water of the Ganges becomes salty

when it reaches the ocean.198

As for Lord Regent Takdrak Vajradhara, he is indeed a great wielder of the vajra possessed of the three sets of vows, a lord in the sea of mandalas, and he remains as the great turner of the wheel of holy Dharma. Radreng Rinpoché, as well, while living in Dakpo in his youth, planted a wooden stake in the face of a rock and left the impression of his foot on a stone that was moved to the great chapel at Radreng, where one can examine it for oneself. He therefore is someone who bears true signs of a great being, too.

In general, due to the degenerated merit of living beings, the attendants of both Takdrak Rinpoché and Radreng Rinpoché mentioned above, and those who followed them, drunk on Manmatha’s wine,199 destroyed their present and future happiness. Many people created a tremendous amount of negativity against their gurus and the Three Jewels through their evil deeds. The deeds of these great lamas, who are protectors of beings in ordinary guise, were influenced by bad attendants. When I reflect on this, I see the truth in the Buddha’s statement in many sutras, motivated by the thought that keeping good or bad company determines one’s happiness, that one must keep good company.

THE FORMAL ENROLLMENT OF HIS HOLINESS THE FOURTEENTH DALAI LAMA

That summer on the grounds of Jaraklingka, at the request of Söchö and other members of the Sadutshang family of Trehor, I gave discourses on the root text of the Guru Puja based on the large manual associated with the practice authored by Kachen Yeshé Gyaltsen (1713–93) and a detailed instruction on Ganden Mahāmudrā based on the root text and commentary authored by Paṇchen Chögyen. Afterward, I received directly from Kumbum Minyak Rinpoché200 oral transmission and explanation of the Essence of Eloquence and Clarifying the Intent of the Middle Way by Jé Tsongkhapa, Dose of Emptiness: Opening the Eyes of the Fortunate by Khedrup Jé, the commentary Meaningful to Behold: A Praise of Jé Tsongkhapa by Gungthangpa, Hortön’s Rays of the Sun Mind Training, Langri Thangpa’s Eight Verses on Mind Training, and the Wheel of Sharp Weapons Mind Training.

That autumn I accompanied His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Drepung Monastery in a grand procession in order to formally commence his religious studies and enrollment in the three seats of learning in accordance with ancient tradition. I stayed in a room on the middle story of the palace at Drepung. As it was tradition for the precious regent to appoint tutors from each of the seven colleges of the three seats, he added to our number by appointing as Tsenshap, in addition to we three existing assistant tutors, Geshé Losang Dönden from Gyalrong House of Loseling, Geshé Chöphel Gawa of Deyang and Geshé Ngödrup Choknyé from Hardong House of Sera Jé, and Thuksé Thupten Topjor of Serkong House of Ganden Jangtsé.

During the actual ceremony, all the monastic and lay officials of the government and the abbots and tulkus of the three monasteries were present in the courtyard of the palace. His Holiness, the regent, Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, myself, and the rest of the seven assistant tutors recited the verses of praise of the Six Ornaments and the Two Excellent Ones entitled Equaling Space201 and Chanting the Names of Mañjuśrī up to the passage that states “. . . plant well the victory banner.” Then the precious regent recited a few lines from the beginning of Maitreya’s Ornament of Realization, which His Holiness and all of us repeated. Then each of the seven assistant tutors, one by one, offered debates on the subject of the Perfection of Wisdom to His Holiness. I recited the verses of auspiciousness at the conclusion of the ceremony. As is tradition, the ceremony ended with a grand feast of ceremonial cookies.

I then accompanied His Holiness as part of his entourage to ceremonies in the great assembly hall, the four colleges, Namgyal Monastery, Tashi Khangsar, and Gephel Hermitage. After the ceremony at Drepung, His Holiness visited Nechung Monastery and invoked the great Dharmarāja Dorjé Drakden through the medium. In private, he showed His Holiness certain sacred objects, including the Sebak Mukchung mask, which I was also able to view.202 Then we made our way through the foothills of the Pari Range to Sera Thekchen Ling Monastery. There I stayed on the upper floor of Denma House near the back door of the main prayer assembly hall. At Sera I again accompanied His Holiness to ceremonies held during visits to the great assembly hall, the three colleges, and Hardong House. His Holiness visited the Phabongkha Hermitage.203 I sought permission to be excused and went to Tashi Chöling Hermitage to pay a visit to the incarnation of Kyabjé Vajradhara. I gave him a long-life empowerment and oral transmissions of several books. After the ceremonies at Sera, as His Holiness returned to the Potala Palace, I did as well.

The great tantric practitioner and holder of the three vows, Geshé Losang Samdrup Rinpoché of Gyalrong, had made a set of two-story-high statues of Jé Tsongkhapa and his spiritual sons that was to be placed into the chapel of Gyümé Tantric College at Changlochen in Lhasa. At his express wish, I performed, together with the monks of Gyümé Tantric College, the elaborate ritual of consecration in its entirety, Causing the Rain of Goodness to Fall in connection with Guhyasamāja. On the concluding day, Geshé Rinpoché himself, who was the patron on that occasion, and Taiji Shenkhawa, who supervised the restoration, attended the consecration ritual. I recited the descriptions of the “Celebration of the Hosts” to the best of my ability and offered the eight auspicious symbols and the eight substances.204

CATALOGING RELIGIOUS TEXTS

At the end of the fall, after His Holiness had settled himself at the Potala, refuge and protector the precious regent told me to complete the cataloging of all the religious texts belonging to the various Dalai Lamas that are kept in the upper and lower libraries of the Potala. Tsawa Tritrul of Sera Mé had been asked to catalog this large collection during the time of the previous Dalai Lama, but the task had been left unfinished. So I and the other assistant tutors accordingly proceeded to carefully examine the texts and complete the task as commanded. Fifteen monks from Namgyal Monastery assisted us to move nearly three thousand volumes that were housed in the library atop the northern wing of the central tower of the Red Palace and to unwrap and rewrap the books in cloth covers.

In the Sasum Chamber in the Potala, we assistant tutors carefully checked the books against the previous catalog, checked the order of their pages, and made new catalogs. Among the books were a copy of the Ratnakūṭa Sutra that had belonged to Jetsun Milarepa’s family and a book with handwritten notations from Omniscient Butön himself. There were also handwritten copies of texts belonging to many well-known masters and realized beings such as Khedrup Norsang Gyatso and Shalu Lochen Chökyong Sangpo. These books contained many personal notes by these masters. At the end of one of the books belonging to the Fifth Dalai Lama, the Dalai Lama had written, “I, the crazy tantric practitioner of Sahor, put this into practice, and many signs of accomplishment have occurred.”

There were many other writings of the Fifth Dalai Lama as well as of Desi Sangyé Gyatso and their commentaries. There were the teachings of the Buddha, the treatises on sutra and tantra that unravel the intention behind the Buddha’s words authored by scholars of every sectarian and philosophical affiliation, the histories of kingdoms and religion, and many works on aspects of knowledge shared by Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. In short, the extent and variety of the collection was inconceivable.

Among the collection were so many exceedingly rare texts that I had not even heard the names of, let alone seen. At that time I did not have an opportunity to look at them at leisure. Immediately afterward we also cataloged the many books that were housed in the sunlight room, Ganden Nangsal, in the eastern wing of the Potala. There were also many books in the library on the lower level. Although we were asked to catalog them later when we had time, they remained uncataloged.

At the beginning of the third month after the Subsequent Prayer Session in my forty-eighth year, the year of the earth-rat (1948), I gave initiations into Guhyasamāja, Vajrabhairava, and Cakrasaṃvara, along with preparations, over a period of five days at the request of the incumbent abbot of the Gyütö Tantric College, Minyak Kyorpön Losang Yönten of Drepung Loseling. These were attended by about four thousand disciples, primarily monks from Gyütö Tantric College, and took place in Ramoché, the Gyütö assembly hall in Lhasa.

At the request of a monastic government official named Losang Gyaltsen, to plant roots of merit for the late cabinet scribe Edrung Tashi Tsering, I gave the initiation of the Great Compassionate One. At that time, the precious tulku who was the supreme incarnation of my sole refuge and friend without equal, Phabongkha Vajradhara, also received initiation into the mandala of highest yoga tantra for the very first time.

The monks of Dakpo Shedrup Ling Monastery in the east came to offer an elaborate long-life ceremony on the occasion of the completion of the ceremony for His Holiness’s enrollment at the seats of learning. At the request of their monastic administrators, at Shidé I gave an audience of around five hundred disciples, primarily monks from Dakpo Shedrup Ling, the initiation into the Great Compassionate One. Afterward, at the request of His Holiness’s personal attendant, the monk-secretary Tsidrung Losang Kalsang, in order to plant roots of merit for his late brother Kalden Tsering, I gave the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī and an eight-day discourse on its two stages to a gathering of over three hundred at Tsemönling Monastery in Lhasa.

That year the government successfully completed the restoration of the assembly hall at Ganden. The ritual assistants from Namgyal Monastery and I accompanied Regent Takdrak Rinpoché to perform the elaborate ritual of consecration, which we did over a period of three days. As the precious regent was physically exhausted and unable to complete the repairing fire-offerings for pacification and increase, I performed them. In celebration of the full restoration of the great hall, I offered tea, sweet rice, and money to the assembly. After the precious regent had left for Lhasa, at the request of Taiji Shenkha Gyurmé Sönam Topgyé, who oversaw the restoration, I offered an initiation of Life-Sustaining Jé Tsongkhapa to the monks of Shartsé and Jangtsé and the entire team of construction workers and their leaders in the courtyard of the assembly hall.

The monks of Gyütö Tantric College are trained in the dimensions of the mandalas for Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava during their annual stay at Drak Yerpa to observe the rainy-season retreat. Although the abbot and chant master would administer exams on the subject, as they only gave oral exams on the three-dimensional mandala, their way of training was ineffective. Without explicitly seeing and becoming familiar with the mandalas in practice, it will be difficult for the less-sharp student to master them as written. As a result of discussing this with the abbot, lamas, and administrators, practical instruction in three-dimensional mandalas was newly instituted and undertaken every year thereafter. Around that time, together with His Holiness, I received the entire collection of initiations from the sealed, secret visionary revelations of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama from Regent Takdrak Vajradhara in the Druzin palace of the Norbulingka.

My forty-ninth year came in the year of the earth-ox (1949). That spring, in the temple of Gyümé Tantric College at the request of a group of newly ordained Gyümé monks, I gave initiations into Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava, permission for the collected mantras of Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava, and permissions for Mahākāla, Dharmarāja, Palden Lhamo, and Vaiśravaṇa to a vast audience of monks from Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges and tulkus and monks from the three seats of learning. I also offered the initiation into single-deity Vajrabhairava to over a thousand disciples who had the commitment to recite the sādhana of single-deity Vajrabhairava.

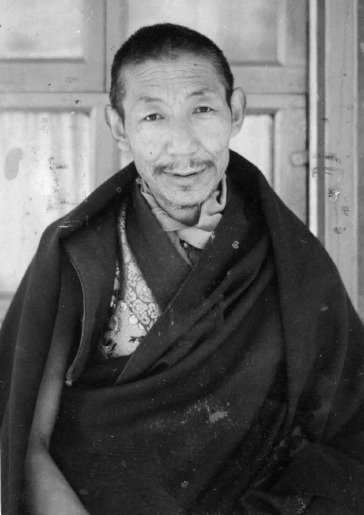

Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché in front of his Lhasa residence, 1949

COURTESY OF PALDEN TSERING

OBSTACLES TO HEALTH

Thinking of planting roots of virtue to counteract the bad astrological circumstances of my forty-ninth year and to support those connected to me, living and dead, in the month of Vaiśākha,205 I sent my attendant Palden together with an assistant to build up my merit by making clouds of offerings at the various shrines and holy places in the south, such as Ölkha, Samyé, and Tradruk. At that time I gradually led His Holiness through the two main topics of Tibetan grammar.206

In the fifth month, to plant roots of merit for the late Losang Dolma at the request of the family of Sönam Rinchen who lived in Jeti Ling in Lhasa, I gave permissions for the deities expounded in the Rinjung Hundred to an audience of more than one thousand disciples, principally monks and incarnate lamas of the three seats of learning, in the assembly hall of Shidé Monastery.

While residing in the Norbulingka Palace during the rainy season, I suffered greatly from dysentery from the twenty-fifth of the sixth month with a relapse of the old intestinal fever. Nonetheless on the second of the seventh month, as all government officials were required to attend the opening ceremony of the Shotön, or “yogurt,” summer folk-opera festival at the Norbulingka, I went to attend it for one hour. Because of this, I had excruciating stomach pain that evening and frequent diarrhea. I was so weak that I fainted and fell before reaching my bed. My attendant Palden burned tsampa mixed with the wind-disorder medicine Agar 35 and applied it to my head, face, and palms, thanks to which I just survived. Early the next morning we asked for the senior director of the Tibetan Astro-Medical Institute, Khyenrap Norbu, and the younger vice chair, Thupten Lhundrup. When they analyzed my urine and pulse, all signs indicated that there was no hope that I would survive. The two doctors would leave the Shotön festival in turns to visit and administer medicine. Thanks to their careful treatment, and by the force of many prayers said to eliminate bad circumstances, and also because my fortune to receive undeserved offerings that turn the heads of [i.e., deceive] the faithful like a whirling firebrand had not depleted, the pain lessened, and I improved slightly.

On the afternoon of the following day, the fourth, Jampa Chösang, a chamber attendant within His Holiness’s personal staff, and Phalha Thupten Öden, the lord chamberlain at the Potala, requested that those who were practicing carrying His Holiness’s palanquin bring over a sedan chair that they used to rehearse with. I was carried on this from the Norbulingka to my house in Lhasa. After the diarrhea had stopped, I was sick for a period of three months with edema.

I had the heads for a half-story-high statue of Amitāyus and for life-size statues of White Tārā and Uṣṇīṣavijayā made in bronze by the excellent craftsmen in Lhasa with the intention of sending them to my monastery in Chatreng, where the bodies would be made. I duly sent the gilded bronze heads, together with ornaments and dhāraṇī prayers for the interior, with Kham-bound travelers who delivered them to my monastery in Chatreng. The monastery had the bodies made and built a temple to Amitāyus to the right of the assembly hall just as I had instructed.

RENEWING THE PROTECTOR SUPPORT SUBSTANCES IN THE POTALA

That winter while residing at the Potala, at the request of His Holiness to renew in their entirety the outer, inner, and secret representations of the most secret Dharmarāja Black Poison Mountain, I rubbed in the substances on the shroud of the previous Dalai Lama in accordance with ancient ritual instructions. On a wrathful day of culmination of stars and planets, state artist Udrung Paljor Gyalpo generated himself as a deity. The artist had previously received Vajrabhairava initiation and had maintained daily recitation and self-generation practice of the deity. After drawing the preliminary mantra diagram on the shroud, I drew the mantra syllables at the places of the sense faculties and at the heart. With the addition of various colors, a painting of Dharmarāja was completed.

As clearly explained in the sealed teachings of the compendiums, I gathered metal name boards with life mantras and the mantra wheels of Yama and Yamāri written on them as supports of his speech and a skull-ornamented mace carved from teak with a phurba dagger at its handle as the support of his mind. A metal trident decorated with black banners bearing mantras was the support for the consort Cāmuṇḍā. Double-edged steel swords with scorpion hilts tempered in blood and poison were supports for the retinue of rākṣasa demons. A bow made from the horn of an uncastrated ox together with a bow-string made of sinews cut with a sword were the support for Viṣṇu. Figurines of a buffalo and a black long-haired yak wearing around their necks nameplates made of the wood of male trees inscribed with mantras were the outer supports. Black banners with mantras and figures drawn on them with weapon-spilled blood, sindūra, lotus blood, ghivaṃ bile, and musk were the inner supports. The skulls of a man and woman whose family line had been broken, on the upper part of which the faces of Yama and Yamāri had self-manifested in relief, made clear by the application of color, and that had the body of wrathful Dharmarāja drawn on a shroud placed at their union were the secret supports. I then gathered the ritual substances and the dhāraṇīs and mantras for insertion. We correctly performed sādhanas to generate the deity and to request him to remain at the end of the full completion of the supports. Having gathered these support substances, we placed them, excluding the statues and thangkas, in a series of boxes as support vessels, and we installed the boxes in the rooms and living quarters of His Holiness in the Potala.

This most secret Dharmarāja, who is a great protector of the teachings of Mañjunātha Tsongkhapa, is exceedingly mysterious and fierce, and on that occasion various signs of the oath-bound protector appeared, various eruptions of turmoil. For example, at the beginning of the process when collecting the support substances, thumping and scraping sounds were heard at night in the room where I was staying. The day when I presented a painting of Dharmarāja to His Holiness to inspect, his chief attendant207 Khyenrap Tenzin was suddenly struck with a seizure. And once when I was leaving my house in Lhasa, the horse on which I was riding threw me off.

And just when I had completed that, His Holiness requested that I renew the ritual supports for Palden Lhamo. With respect to her images, I was not asked to renew the painting of Lhamo, as the existing one had been the support of the deity for successive Dalai Lamas and had spoken directly to His Holiness.

I correctly gathered the substances as taught in His Holiness the Second Dalai Lama Gendun Gyatso’s Presentation of the Three Acts of Lhamo208 and in the manual of His Holiness the Great Fifth Dalai Lama’s sealed secret visionary revelations. The Tantra of Ḍākinī Meché Barma209 written in gold served as the support of her speech. A mirror with bhyōḥ written on it was the support of her mind. A sandalwood vajra club ornamented with a black banner bearing mantras, and the skull of an illegitimate child filled with charmed substances — various types of blood and medicinal offerings — were the support for her activity. A raven figurine made from black cloth stuffed with medicinal grain and human skin on which a consecrated picture of Palden Lhamo’s body had been drawn were the outer support. The faux corpse of a bastard child made of black cloth was the inner support — this was stuffed with a piece of burnt wood used in a cremation and a life-tree trident smeared with poisonous blood. These had been wrapped in a corpse shroud around which the long mantras of calling, expelling, and slaying Lhamo had been written out in weapon-spilled blood. The faux corpse had its heart stuffed with leaves that had not been blown to the ground by the wind and had the mantra of Palden Lhamo written on one side and the image of her body drawn on the other for use as dhāraṇī, and these were smeared with the juices of sexual union. The body was filled with various types of blood, grains, and mantras with interwoven text, and the whole was draped in a black coat. A victory banner was placed in its hand, and a peacock feather crest set upon the head.

One secret support was a representation of the heart of a bastard child whose three channels had not deteriorated. The heart was stuffed with pebbles drawn from the depths of Divine Lhamo Lake in Chökhorgyal and never exposed to the sky, and phavaṃ stones210 upon which bhyōḥ was written with lotus blood. Another secret support was an arrow shaft made of a stalk of wild bamboo with seven segments, grown at Draknakpo and decorated with the unsinged feather of a crow. At the middle of the arrow was the stacked seven-part bhyōḥ mantra. From the base of the feather upward was drawn the tutelary deity, her mantras of calling, expelling, and slaying, along with interwoven text, and the arrow was tipped with a metal arrowhead that had been previously tempered in poisonous blood. We also gathered such things as tiger cloth and leopard cloth, a modest hair braid,211 black banners bearing mantras, mirrors, decorative riding tassels, as well as flat-bladed swords and ritual daggers, a golden sun and silver moon fashioned by the craftsmen in a single sitting, a weapon ball made of thread,212 fatal red curses,213 and black and white dice stones.214

After having well produced and consecrated the substances and placed them in a hard black lacquer box with drawings of fearsome weapons on it, we distributed the boxes in front of the images of Palden Lhamo in the rooms and living quarters in the Potala.

At that time, His Holiness and I received initiation into seventeen-deity Sitātapatrā based on the manual by Kyishöpa215 from Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché in the Jangchup Gakhyil quarters on the upper floor of the Norbulingka Palace.

In my fiftieth year, the year of the iron-tiger (1950), as I was requested to plant roots of merit on behalf of the late Tsamkhung nun Phuntsok, in the spring of the year at Lhasa’s Tsamkhung Nunnery I gave the great initiation into Ghaṇṭāpāda’s five-deity Cakrasaṃvara and Ghaṇṭāpāda’s body mandala, an explanation of the generation and completion stages of Ghaṇṭāpāda’s body mandala based on experience, the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī, and an explanation of its generation and completion stages based on experience to an audience of a little more than one hundred disciples.

As requested by the abbot of Sera Jé, Thupten Samten of Trehor House, during the summer retreat in the Khenyen College assembly hall, I gave teachings based on my experience on the stages of the path using the Easy Path, the Quick Path, and the Words of Mañjuśrī. I also gave teachings on the Seven-Point Mind Training and the six-session guruyoga for over one month to about five thousand disciples, including the monks from the Jé, Mé, and Ngakpa colleges of Sera as well as many monks who came back and forth each day from Lhasa and Drepung in their fervent quest for teachings. In the middle of that sea of scholars who knew these lengthy texts by the hundred without needing to rely on others, I couldn’t help but feel like a donkey disguised in leopard skin.

Among those listening to the teachings at that time was one of the most well-known among the great masters of the three seats, Geshé Yeshé Loden of Drepung Loseling. One day, after the teaching on the stages of the path, he came to visit me to express his pleasure in the discourse. He told me, “Your recent discourse was not only excellent because of your explanation of the words but was greatly beneficial in terms of their application.” I appreciated his comments, but I thought to myself, “Little does he realize that I lack any personal experience and that my explanations of the teachings were like an actor’s speech, narrations of the teachings without any conviction.” Through the incomparable kindness of the father lama, I was merely repeating his teachings as if I were conveying messages.

ARRIVAL OF COMMUNIST CHINESE AND HIS HOLINESS’S ENTHRONEMENT

That summer brought several ominous occurrences. A comet appeared and could be seen at dawn in the skies over Bumpa Mountain to the south of Lhasa. One day at about nine in the evening while I was teaching the stages of the path at Sera, we heard a noise from the sky like gunfire that seemed to come from the area south of us where the Drashi military encampment was situated. Just afterward a strong and long earthquake struck, and the bells on the gilded roof ornaments on the top floor of Sera Jé assembly hall could be heard ringing by themselves. As I was living on the top floor, I was at first quite alarmed. But then I recalled that if I had not committed the causes, I would not meet the consequences, and that the results of actions already committed are unavoidable. Thus I maintained my composure. The sound of gunfire from the sky and the earthquake occurred in regions all over Tibet at the same time. I took this as an ominous sign portending the imminent arrival of the poisonous wave of the barbaric Red Chinese.

With the pure intention to be of help and service to Buddhism, Beri Getak Tulku Rinpoché of Trehor went to Chamdo with stainless faith and devotion to mediate between Tibet and China and to take measures to prevent the deceitful settlement of Chinese troops in Tibet. That great Rinpoché had previously received many teachings of sutra and tantra directly from the supreme presence of Regent Takdrak Rinpoché. As he and I shared a deep bond of friendship as teacher and disciple in the past, each of us showed authentic faith and affection to other. He hoped to do whatever he could to be of benefit. Although I had no concern whatsoever that he would harmfully betray us, like a karmic obstacle shared by a group, Getak Tulku came under the suspicion of his own government due to the actions of certain individuals who were seeing ghosts in their own shadows, and he was held for a long time in Chamdo and ended up dying there in custody, some say from poisoning. I was greatly distraught with sorrow when he could not return, but there was nothing I could do.

On the eighth of the ninth month, the Communist Chinese Army unexpectedly marched into Chamdo. The Tibetan soldiers stationed there were unable to defend it and lost ground. The Chinese arrested a large number of civilian and military leaders, including Minister Ngaphö, the governor general of Domé region, and his staff at Dugu Monastery. Because of this grim situation, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Regent Rinpoché, and the cabinet and the secretariat216 invoked the great Nechung Dharmarāja and the Dharma protector of Gadong in a trance of their mediums in the sunlight room at the Norbulingka.

The Gadong oracle made full prostrations before His Holiness and said, “The time has come for Your Holiness to assume the burden of governing the land of snows.” His Holiness received again a similar prophetic statement from Nechung. Immediately afterward, the cabinet, the secretariat, and the Tibetan National Assembly formally requested His Holiness to assume religious and temporal powers, and His Holiness granted his supreme consent. On the seventh day of the tenth month, Regent Takdrak Rinpoché abdicated the highest office, and on the eighth day (November 17, 1950), the golden wheel of religious and temporal rule in the land of Tibet was placed in His Holiness’s hands. His enthronement was celebrated at an elaborate ceremony held in the Sishi Phuntsok hall of the great Potala Palace. That day, every prisoner serving time in prisons throughout the entire country of Tibet — including Radreng Dzasak, Khardo Tulku, Tsenya Tulku, and Minister Kashöpa — were simultaneously pardoned and freed.

FLIGHT TO DROMO AND THE SEVENTEEN-POINT AGREEMENT

Following this, on about the tenth of the eleventh month, His Holiness responded to the increased Chinese presence by appointing the ecclesiastical secretary Losang Tashi and the finance secretary Tsewang Rabten of Dekhar (Lukhangwa) as deputy prime ministers. His Holiness, the former regent Takdrak Vajradhara, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, the cabinet ministers, and a small retinue of monastic and secular members of the upper and lower departments of the government left the Potala, secretly stopping at the Norbulingka before riding to the region of Dromo. I traveled in His Holiness’s party, along with Lhabu, Palden, Gyümé Ngakram Tsultrim Dargyé of Trehor, and a small number of servants. We departed Lhasa early in the morning and stopped for the night at Nyethang Tashigang. Among the statues in the Tārā temple at Nyethang, I saw the statue of Tārā that was the tutelary deity statue of Lord Atiśa that spoke, and I also got to see the memorial stupa of Serlingpa that Atiśa always carried with him.217

The next morning we arrived at Lower Jang, where the monks of the three seats who had been attending the Jang winter session218 were waiting on the roadside, as they had heard that His Holiness and his entourage were coming. Because His Holiness was disguised in ordinary clothes, he passed the monks unnoticed. It was heartbreaking when Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and I arrived there, the monks surrounded us on all sides, throwing scarves and money left and right. Openly weeping, they held on to the reins of our horses and would not let us go. We talked with them, reassuring them that they would see us again before long. We left the money that the monks had thrown to us where it fell on the roadside, so the people in the villages nearby should have found some rich pickings.

That night we stayed in a village in Chushul. Many monks of the great monasteries had followed us there. Setting out from Chaksam ferry landing, we saw the shrines of the siddha Thangtong Gyalpo at the hermitage of Chuwori. Then passing through the Gampa Pass, Yardrok, Kharo Pass, Ralung, Gyantsé, Phakri, and so on, we arrived in Chubi in Lower Dromo, where His Holiness stayed at the residence of the governor of Dromo. My retinue and I along with members of His Holiness’s family — his mother, his brother Taktser Rinpoché, and so on — were distributed to sleep on the upper and lower floors of a household called Chubi Labrang. It was decided that His Holiness and his entourage would stay in Dromo, given the circumstances both domestically and abroad. From Dromo, both the negotiations for peace talks with the Chinese and the appeal to other countries for support could be carried out. Lhabu, Tsultrim Dargyé, and I remained there, but as Palden had never been on a pilgrimage to the sacred places in India and Nepal, I sent him to India with the merchant Losang Yeshé as his assistant. Since I gave him a fair amount of money with which to make clouds of offerings at the holy places, extensive offerings were made there.

On New Year’s Day of the iron-rabbit year (1951), when I turned fifty-one, His Holiness, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, and I, along with the ritual assistants of Namgyal Monastery, made offerings to Palden Lhamo. The cabinet ministers and other government officials held a brief New Year ceremony at the office of the governor and presented scarves to the former regent, Takdrak Vajradhara, who was staying at Jema in Lower Dromo. On the third day of the New Year, after making offerings to the protectors, I accompanied His Holiness on a visit to the Kagyü monastery in Lower Dromo. After spending two days there, His Holiness and the entourage shifted residence to Dungkar Monastery in Upper Dromo, where I stayed in the quarters of Böntsang Ngawang Tsöndrü at Dungkar Monastery.

His Holiness upgraded my position, elevating my Darhan rank of assistant tutor so that I would sit in front of the cabinet at ceremonies, as it would be inappropriate for me to be seated behind the lay ministers. His Holiness received me in audience and held a brief ceremony with a ceremonial scarf to mark the occasion.

As Khyenrap Wangchuk of Tashi Ling, who was an acting monastic cabinet minister, had asked that I plant roots of virtue for his brother, the treasurer Gyaltsen Namgyal, I gave a discourse on the stages of the path according to the Quick Path and concluded with a bodhicitta-generating ceremony to about three hundred disciples in the assembly hall of Tashi Chöling Hermitage at Dungkar Monastery in Upper Dromo. As I had close guru-disciple connections with the Galing Gang Bönpotsang family since the time of their grandfather Pha Dönyö, at their request I went to their household and performed a prosperity ritual and gave long-life initiations, staying there for a few days. Because of my past guru-disciple connections with the previous and the most well-known Dromo Geshé Rinpoché Ngawang Kalsang and with the monks of Dungkar Monastery, I made offerings to the monks of food and money and gave four tsipar ornaments made of brocade appliqué with banners for the tall pillars of the assembly hall.

Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché on a mule en route to Dromo, 1950

COURTESY OF PALDEN TSERING

On the eighth day of the third month, during the traditional government torma offering of the eighth, my attendant Palden joined the monastic service of the government. While residing in Dromo, His Holiness observed an approaching retreat on the root mantra of single-deity Vajrabhairava, an approaching retreat of the Great Compassionate One according to the Lakṣmī tradition, and a retreat on the inner sādhana of Dharmarāja, for which I served as his assistant.

On that occasion, Ngaphö Ngawang Jikmé, who was a cabinet minister at the time, Dzasak Khemé Sönam Wangdü, monastic secretary Thupten Tendar (Khendrung Lhautara), junior monastic secretary Thupten Lekmön, and others were sent to China as representatives of the Tibetan government. Coerced by the Chinese, the team signed the so-called Seventeen-Point Agreement.219 Ngaphö and a few of his staff members returned to Tibet from China via Kham, while Dzasak Khemé and Thupten Tendar returned to Dromo via Hong Kong and India. At the very same time Zhang Jingwu, a representative of the Red Chinese that had been sent to Tibet from China, arrived in Dromo along with Alo Butang. They met with His Holiness and discussed “the peaceful liberation of Tibet” and their plans to improve the land and the lives of the people of Tibet. Making many sweet promises, they insisted that His Holiness and government officials immediately return to the capital in Lhasa. Having considered the situation, His Holiness left Dromo at the beginning of the fifth month.

RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIES AFTER RETURNING TO LHASA

His Holiness traveled through Phakri, Gyantsé, Nakartsé, Yardrok, Samding, Taklung Monastery, Paldi, Nyasok, Sé Chökhor Yangtsé, and Nyethang Ratö, and was received by a reception party at Tsakgur Park. Then, having visited Takdrak Hermitage and other places along the way, he was received with an official government reception at Kyitsal Luding. From there His Holiness and entourage traveled in an elaborate, traditional procession to touch his foot once again to the grounds of the Kalsang Phodrang Palace, Norbulingka. To fulfill the request of monks of Nenying Monastery, Shiné Monastery in Gyantsé, and Chökhor Yangtsé, I offered summary discourses on assorted topics. I paid my respects to former regent Takdrak Vajradhara, who had left Dromo ahead of us and was staying at his hermitage.

After we arrived in Lhasa, at the invitation of the jeweler Kalsang and his daughter, the nun Ngawang Chözin of Gomang Khangsar in Lhasa, I went to Nechungri Nunnery for a few days to give the nuns the great initiation into Ghaṇṭāpāda’s five-deity Cakrasaṃvara and the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī to help establish the practice of Vajrayoginī self-initiation at the nunnery. As I had been invited to visit the quarters of the monks of Samling dormitory in Pombor House at Sera, I went there and made offerings and gave them some money to put toward their annual picnic to mark the end of the rainy season. Then as Phara Choktrul Rinpoché had invited me, I went to Ganden and gave the great initiation into Guhyasamāja Akṣobhyavajra along with its preparatory rite in Phara House over a period of three days to a large gathering of masters and lamas of both Jangtsé and Shartsé colleges.

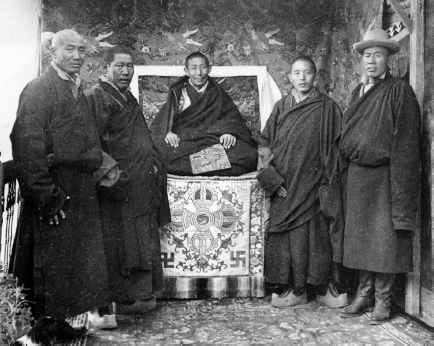

Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché and labrang staff at his Lhasa residence, 1951. From left to right are his senior attendant Lhabu, manager Losang Döndrup, personal attendant Kungo Palden Tsering, and merchant/attendant Losang Yeshé.

COURTESY OF PALDEN TSERING

With merchants returning to Kham, I sent gilded bronze heads for three statues that I was having erected at Samling Monastery in Chatreng — a statue of Mañjunātha Tsongkhapa one and a half stories high and statues of Gyaltsap and Khedrup that would be a little larger than life-sized — along with various printed dhāraṇīs to fill them. I had the heads of the statues produced in Lhasa because of superior craftsmanship there. The monastery itself had the bodies built and constructed the temple just as I had requested.

In the third month of my fifty-second year, the water-dragon year (1952), His Holiness received the Kālacakra initiation from his tutor Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché in the ceremonial hall of the Potala, and I received it again as well. From the tenth of the fourth month, over a period of nine days, I gave a large audience of earnest recipients the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī and its mantra extraction along with a teaching on its two stages. This teaching, given at the request of Dawa Dargyé, a staff member at Kundeling Labrang, was given according to practice of the Great Secret Explication for Disciples.220 Sometime later, at the behest of Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, I offered the great initiation into sixty-two-deity Cakrasaṃvara in the tradition of Luipa along with its preparatory rite.

To fulfill the request of Bayer Tsering Drolkar, the wife of Mr. Mentöpa, I gave the great initiation into five-deity Cakrasaṃvara according to the external mandala in the tradition of Ghaṇṭāpāda, the great initiation into the body mandala, instruction in the two stages of Ghaṇṭāpāda’s body mandala, along with experiential teachings on the six Dharmas of Nāropa. These teachings took place over a period of about twenty days, beginning on the tenth day of the fifth month, in the assembly hall of Shidé Monastery, and were attended by an audience of nearly a thousand disciples that were mostly tulkus and geshés.

After the rainy-season retreat at the Norbulingka Palace, I went to the hot springs in Tölung. On the way, since Gyümé Tantric College was in the middle of their Dharma session while observing a later rainy-season retreat at Chumik Valley, I spent three days there and made offerings to the assembly. The monks were practicing the melodies and rhythms of the tantric college chants, and I went briefly to the individual regional houses, as they invited me. I also visited the nearby small huts where figures such as Kunkhyen Jamyang Shepa and Longdöl Lama Rinpoché had lived.

Thereafter I spent a fortnight at the hot springs for my health. It just so happened that the director of the Astro-Medical Institute, Dr. Khyenrap Norbu, and Chögön Rinpoché of Dechen Chökhor Monastery in the Gongkar Truldruk tradition were there at the same time. We all knew each other quite well. Chögön Rinpoché had a vast and profound knowledge of both religious and secular matters and was quite articulate. The director of the Astro-Medical Institute, too, was quite well versed in the ten arts and sciences,221 with a knowledge like the great statesman Desi Sangyé Gyatso,222 and was also learned in history. Because of their stimulating conversations, I enjoyed my visit to the hot springs so much that I didn’t know where the time went.

After that encounter at the hot springs, at the request of Dingkha Rinpoché of Tölung, I went to Dingkha Monastery and gave the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī. Then, at the invitation of Chusang Monastery, the monastic seat established by the venerable Dromtsun Sherjung Lodrö, who was a direct disciple of Jé Rinpoché, I offered initiations into thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava, Sarvavid, and so on. I then went back to Lhasa.

During this same period, to support the wishes of His Holiness, I oversaw the production of new thangka paintings of single-deity Vajrabhairava, the five emanations of Nechung Dharmarāja, and Shukden in his five aspects. Since the painter, Udrung Paljor Gyalpo, had previously received the initiation of Vajrabhairava, I gave him the permissions of the five emanations of Nechung. I generated him as a deity, and the painting materials and equipment were blessed. The blessed solutions were applied to the canvases, and the mantras were written according to the manuals and texts of the individual deities. On the backs of the thangkas of the five emanations of Nechung and Shukden, I drew the life-force wheel and wrote the life-force mantras with wishes and prayers on a day when the eight classes of spirits were active.223 When these were fully completed, the thangkas were consecrated.