MY APPOINTMENT AS JUNIOR TUTOR

IN MY FIFTY-THIRD YEAR, the year of the water-snake (1953), at the request of Chözé Gyatruk of Meru Monastery I offered initiations into Ghaṇṭāpāda’s five-deity Cakrasaṃvara and thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava along with its preparatory rites to an audience of a little more than one thousand in Meru’s assembly hall. Over the summer, at the wish of His Holiness, the government expanded the northern section of the Shöl Kangyur printing press at the base of the Potala Hill and constructed a new temple to enshrine the newly made statues of Vajrabhairava, Kālacakra, Palden Lhamo, and Ekajaṭī, each of which were three stories high. I took responsibility for overseeing the process at every step along the way, from blessing the materials, guiding the craftsmen to visualize themselves as the deities, and laying out measurements for the statues, to inspecting the designs and inserting the dhāraṇīs and relics inside the statues. Afterward His Holiness attended the consecration of the statues for three days and gave his blessings with the ritual tossing of grains.

I had a one-and-a-half-story appliqué thangka of Dharmarāja and his consort in union as its principal figure, surrounded by Jé Rinpoché, Vajrabhairava, Karmarāja, and Shukden, sewn from pieces of fine brocade. I had this sent to Samphel Ling Monastery in Chatreng to be displayed during the celebration at the conclusion of the gutor ritual.224

In the fall, at the request of Geshé Yeshé Gyatso of Gungru House of Gomang College of Drepung, over a period of twenty-three days in the assembly hall of Gomang College, I offered teachings on the stages of the path based on the Easy Path, the Quick Path, and the Words of Mañjuśrī to an audience of nearly four thousand, comprised principally of monks from the three seats, exemplified by present and former abbots and tulkus. I felt like a parrot reciting the maṇi as I gave dry explanations amid a sea of erudite masters. The incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara himself also attended to receive the teaching on the stages of the path for the first time. At the request of Ön Gyalsé Choktrul Rinpoché, I also offered the same gathering permission for White Mañjuśrī according to the system of Mati.225

At the beginning of the tenth month cabinet minister Surkhang Wangchen Gelek and monk secretary Chöphel Thupten came to visit me in my quarters in the Norbulingka. Representing the cabinet and the secretariat of the government, they told me that my duties of offering religious instructions to His Holiness alongside Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché had been well performed and that I was to be commended for it. Further, as His Holiness was to receive full ordination the following year, Ling Rinpoché would be promoted to the position of senior tutor and I should accept the position of junior tutor. They told me that at the recommendation of the cabinet and other departments, His Holiness had given his approval and that I should soon follow the necessary ceremonial procedures to assume this role in order to offer His Holiness the entire vast and profound teachings of sutra and tantra in the manner of “pouring from one vessel to another.” They then presented me with a ceremonial scarf and the representations of enlightened body, speech, and mind.

The Ornament of Realization says of tutors:

A mind undaunted and so forth,

teaching the lack of a nature and so on,

casting off all that opposes it,

this makes for a consummate tutor.226

Although I did not possess even a hundredth of a hairbreadth of the inner and external qualities of a tutor as expressed in this verse, I gathered up courage to join the ranks of the fearless lions like an aged dog and accepted the offer.

Without delay I accepted the scarf symbolic of the ordered change in post and had a propitious inaugural meeting with His Holiness. On the actual day of assuming the post I made a thousand offerings227 at Lhasa’s Tsuklakhang, Ramoché, and the Avalokiteśvara temple in the Potala Palace. After visiting the sacred images, I went to the Norbulingka Palace, where I prostrated before His Holiness in the Jangchup Gakhyil chamber on the top floor and presented him with a scarf and the representations of the body, speech, and mind. His Holiness in turn gave me a scarf with the three representations and a sacred statue of Mañjuśrī made of bronze. In connection with this exchange, I gave a reading transmission of Fifty Verses on Guru Devotion along with a brief introductory discourse that began with the benefits of developing bodhicitta. Afterward a banquet of ceremonial cookies to mark a propitious beginning was arranged by the government in the ceremonial hall of the sunlight room. I made prostrations with the deepest reverence to the supreme leader of all beings in saṃsāra and nirvāṇa, who was seated magnificently glowing like a million suns on a throne of fearless lions. I then presented him with a scarf with the three representations and gifts. The government, as well, presented invaluable gifts to me, and in accordance with tradition, I accepted scarves from the cabinet ministers, the lord chamberlain, and other monk and lay officials, from the highest down to the sixth rank (letsenpa).

After the ceremonies in the Norbulingka Palace, I returned to my residence in Lhasa, where government officials of various ranks, representatives from the three seats, their colleges and labrangs, and many others with whom I had religious and secular connections came in a long line bearing gifts.

Dagyab228 Chetsang Hothokthu first came to Lhasa that year. After he went to have an audience with His Holiness at the Potala, he came to my quarters, where I greeted him and paid my respects. That winter, I served as assistant to His Holiness as he observed the approximation retreat of the mind mandala of Buddha Kālacakra along with the repairing ritual fire offering.

THE DALAI LAMA TAKES FULL ORDINATION

In my fifty-fourth year, the wood-horse year (1954), His Holiness was to take full ordination as a bhikṣu at Lhasa’s Tsuklakhang during the festival that commemorates the Buddha’s performance of miracles in India. Dagyab Chetsang Hothokthu Rinpoché had also requested that His Holiness preside over the prayer sessions at the same time. To attend these two events, His Holiness traveled in a large ceremonial procession, as was the custom, from the great palace to the Ganden Yangtsé chambers on the top floor of Lhasa’s Tsuklakhang. I also took up residence in the quarters atop the temple in the Nangsi guest room.

On the fifteenth of the first month, before the sacred Jowo Śākyamuni statue, His Holiness received his full ordination directly from the Sharpa Chöjé, Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, who acted as both preceptor and master, attended by the incumbent Ganden Throneholder Thupten Kunga of Sera Jé, who acted as recorder of time, and myself, who acted as the interviewing master. Former Ganden Throneholder Minyak Tashi Tongdü from Drepung Loseling, the Jangtsé Chöjé, and the various adjunct tutors filled out the required assembly of ten fully ordained monks. By purely receiving the precepts and vows of a fully ordained bhikṣu, which are the basis of training, amid an assembly of ten fully ordained monks by means of the “current excellent and faultless rite,” he preserved the tradition of the great ceremony that invests one as the crown jewel of all bearers of the Vinaya.

As the interviewing master, it fell to me to ask His Holiness a series of questions, such as “Are you not a non-Buddhist?” “Are you not a thief?” “Have you not killed your father?” and so forth. I felt extremely uncomfortable asking such questions to His Holiness, who is the supreme leader of the religious and temporal affairs of Tibet, the land of snows. But since this was conducted according to the ancient traditions of monastic discipline, I mustered the courage and put these questions to him.

That day during the auspicious offering of a feast of ceremonial cookies that had been arranged by the government within the vast courtyard of the Tsuklakhang, I was asked to recite the treatise for the symbolic mandala offering of the universe to His Holiness. In this treatise I recited descriptions of the supreme qualities of the enlightened body, speech, mind, and activities of His Holiness as well as the history of monastic vows in Tibet down through the ages, the fundamental importance of the Vinaya to the teachings of the Buddha, and how the monastic discipline serves as both teacher and teaching. From the following day, when the general population of Lhasa, high and low government officials, the labrang of Tashi Lhunpo, and so on made elaborate traditional offerings one after the other, I also recited explanation of the ritual mandala as requested.

After the Subsequent Prayer Session, at the request of Lady Losang Paldrön to sow roots of virtue on behalf of her late husband Rimshi Chabpel, I offered in Lhasa’s Meru assembly hall the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī and an experiential discourse based on the manual Staircase of Pure Vaiḍūrya229 and Shalu Khenchen’s Quick Path to Attain Khecara230 to an audience of nearly four hundred, including the incarnation of the supreme refuge Phabongkha Rinpoché, Dagyab Hothokthu, and Dromo Geshé Rinpoché. Following that, at the request of the monks of Dakpo Shedrub Ling Monastery who had come to make congratulatory offerings to His Holiness, I gave a discourse on the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita to the entire assembly of monks in Evaṃ Hall on the top floor of Lhasa’s Tsuklakhang.

On the fifteenth of the fourth month, I conferred novice ordination on the incarnation of the supreme refuge Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara and bestowed on him the name Ngawang Losang Trinlé Tenzin.

TRAVELING TO CHINA

It happened that a meeting called the National People’s Congress was to be convened in Beijing.231 The Chinese representative in Tibet Zhang Jingwu and a member of his staff, Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal, came to visit me several times to invite me to attend the conference to represent the monastic population in Tibet along with representatives from the three provinces of Tibet: Central Tibet, Kham, and Amdo. However, I declined the invitation. After they brought the situation to His Holiness’s attention and pressured him, he told me, “This time you should accept it.” Because I wanted to avoid causing him trouble, I could not refuse. Thereafter it was decided that His Holiness, our supreme refuge and lord, the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché, we tutors, the cabinet minister Ngaphö Ngawang Jikmé, His Holiness’s sister Tsering Drölma, and Dzasak Trethong of Tashi Lhunpo Labrang would go from Central Tibet.

His Holiness, Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, Gyalwang Karmapa Rinpoché, Mindröling Chung Rinpoché, and the cabinet along with a retinue of government officials set out from the capital on the tenth day of the fifth Tibetan month. I set out with my assistants Lhabu, Palden, Losang Sherap, Losang Yeshé, and Namdröl at the same time. On the way, His Holiness kindly made a pilgrimage to Ganden Nampar Gyalwai Ling at Mount Drok. On that occasion my labrang offered clouds of offerings at the sacred objects, and I offered the gathering assembled in the great hall tea, sweet rice, and a sum of money for each monk, and I established a fund for annual monetary offerings. I invited His Holiness to preside over the prayer session on the golden throne of Lama Tsongkhapa, and with the recitation of treatises as well as an explanation of the ritual mandala, I offered as clouds of offerings whatever actual goods I had.

The high-ranking and senior members of the entourage traveled by car from Ganden up to the base of Kongpo’s Ba Pass, and the rest traveled on horseback. Since the highway up to Powo Tramo had not yet been finished, the entire retinue rode on horseback through Kongpo Gyada, Ngaphö, Drul, Shokha, Nyangtri, Demo, and Lunang and eventually arrived in Powo Tongyuk. On the way we traveled through extremely thick jungle, where the branches of the trees were so densely interwoven that one could not see the sky and the terrain was very rough. Not only did we need to traverse many passes, ravines, and rivers each day, we were caught off guard by unusually strong summer rainstorms, the likes of which had not been seen before. Most of us had to walk on foot up and down the hills. We were terrified of the possibility of boulders hurtling down on us in landslides or of falling thousands of feet into deep gorges. We had to make our way falteringly across makeshift wooden bridges built over torrents swollen by the heavy rains, their spray filling the air. As Jé Lhodrak Marpa said:232

Never was there an end to precipices and rivers,

never an exit from dense jungle.

When I recall these fearful roads,

my breath and heart still tremble to this day.

Marpa was speaking of the notorious trails and courses of Tsari,233 but our paths were even more dangerous and difficult. For a month it was exhausting, both physically and mentally, a great tribulation.

At Powo Tramo some Chinese motor vehicles were there to meet us, and I traveled with the entourage in these. For the overnight stopovers, the Chinese provided poor accommodation in shabby tents, and we were given clear tea to drink and had our meals in the kitchen alongside Chinese road workers. There are lines from tantric training that say, “Brahmans, outcasts, and dogs — all are seen as inseparable, manifested as one.” So in this observance of sacred practice of highest yoga tantra, we all ate our meals from the same containers.

From Tramo I sent home the horses, mules, and some of the attendants that we had brought with us from Lhasa, and their return journey was even more fraught with difficulty. We went on through Tsawagang and Drakgyab Kyilthang and reached Jampaling Monastery in Chamdo district. As arrangements had been made for my stay, I spent one night at the residence of Shiwalha, where because of my past guru-disciple connection with Shisang Rinpoché in Lhasa, I was given a warm reception.

From there we crossed the great river via Kamthok portage in Dergé and crossing over a high-altitude pass in Dergé called Tro Pass, traveling via Yilhung, Dargyé Monastery in Trehor, Karzé Monastery, and Tau Monastery, we arrived at Dartsedo. At Dargyé Monastery I met the great master Geshé Jampa Khedrup Rinpoché, who had established a dialectics institute at Dargyé Monastery and had made the monks very conscientious and peaceful in their conduct by propagating teachings on the stages of the path. At Beri Monastery, I met the incarnation of Getak Tulku and Shitsé Gyapöntsang together with the members of his labrang and many other past patrons and disciples. They gave me a lot of provisions for the journey, but I was only able to carry two bags of tsampa.

Although Karzé Monastery had arranged accommodations for His Holiness’s stay, the Chinese representative Zhang Jingwu ordered, “You must stay in the quarters prepared for you by the Chinese.” As His Holiness had to stay in the Chinese headquarters, I also had no choice but to stay there too. Döndrup Namgyal of the Gyapöntsang family along with his son and the learned Gyapön Chözé Ngawang Dorjé came to visit me there. Lakak Tulku and some representatives of the monastery and region of Chatreng had come to Karzé to meet me and had been waiting for us for one month. As the Chinese guards would not allow them in to visit me, I went out to the tent where they were staying to meet and converse with them for an hour.

From Dartsedo, I dispatched my traveling companions Losang Yeshé and Namdröl to Chatreng via Lithang for the time being. My personal attendant Lhabu along with Palden and Losang Sherap accompanied me to China. After Dartsedo we crossed the high pass of Erlang and arrived in the first Chinese town called Ya’an. As I had been traveling all day in motor vehicles since Powo Tramo, I suffered headaches and nausea, eating less and less each day. As Muli Kyabgön Tulku and the Muli tribal king with his retinue were there, they came to visit me. At last we arrived in Chengdu, from where His Holiness and a few members of the entourage, including tutor Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and myself with Lhabu, went to Xian by airplane. All-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché had gone to Xian from Tsang via the northern road, and so the spiritual father and son234 met each other there. I went along with His Holiness to visit the pilgrimage site of the temple wherein Lhasa’s Jowo Rinpoché had previously been kept, where one can see the empty throne on which the Jowo sat. Next we went to Beijing by train. In Beijing, His Holiness, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, and myself stayed in the visitors’ residences called Yikezhao.

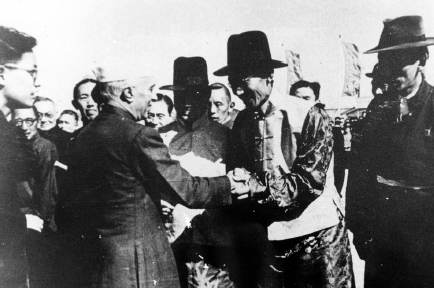

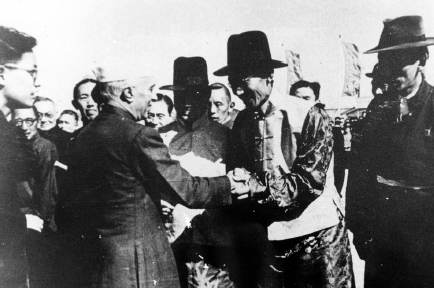

Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché receiving Indian Prime Minister Nehru at Beijing airport in 1954, flanked by ministers Surkhang, Ngaphö, and Neshar, with Paṇchen Rinpoché’s father and attendant Palden Tsering behind them

COURTESY OF PALDEN TSERING

WITHIN CHINA

As the congress was to commence shortly, after just two days with no time to rest we were required to attend the small preliminary committee meeting and then the actual National People’s Congress, which held two sessions a day over a period of a month. It was quite a strain due to our inability to understand Chinese, the nature of the politics, and so on. Each day when the meeting adjourned, His Holiness and Paṇchen Rinpoché were invited to tour different industrial plants and to watch films and stage shows, on which occasions we were required to go along with them. In short, the fact that we were always required to be on the move from six in the morning until ten or eleven at night, with no time to rest, except during meal times, made it an exceedingly stressful ordeal.

One fortunate thing that happened during that time was that the great Lharam Geshé Sherap Gyatso of Lubum, who was second only to youthful Mañjuśrī in his discernment of the ten arts and sciences and was overflowing with kindness, had come to the congress, and we were able to share some time with one another on several occasions. As I had not seen Geshé Rinpoché for many years, we both felt a combination of sadness and joy, like a reunion of the dead. We exchanged news of the intervening years, and I had the great opportunity to ask him questions and seek his advice. I offered him two thousand dayang coins.235

Once the Chinese asked me to broadcast a message to Lhasa over the radio about my impressions of the progress in the region of China and how the masses were free and happy, and how the Chinese had only uncontrived goodwill toward the people of Tibet. I prepared a draft of the message as I saw fit in the circumstances and gave it to the Chinese, as they had demanded to review it. I had to accept their edits and changes and was told to read it as they had written it. In Lhasa, many laymen and monks from all walks of life, not knowing that I was under the dominion of Chinese devils, thinking, “He protects and supports the Chinese with flattery,” spoke disparagingly of me, like the illusion of seeing a snow mountain as blue. But how could I blame them? They weren’t psychic, after all.

Since the memoir authored by His Holiness, My Land and My People, clearly covers the proceedings of the congress, the rights of the people, and the meetings between His Holiness and Mao Zedong on various occasions, I needn’t elaborate on them here. As for the hospitality of the Chinese in terms of accommodations and food, they made a great effort to impress us during the early stages of their deception.

I then accompanied His Holiness on his visits to the great cities of China: Tianjin, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Shanghai, and so on. We were required to tour many industrial plants in those cities and found no chance to relax and rest.

ARRANGING A VISIT TO KHAM

When we arrived in Shanghai, His Holiness received invitations from the monasteries of Ba, Lithang, Gyalthang,236 and other monasteries in southern Kham. But the Chinese objected to accepting the invitations, saying that there were no motorable roads to southern Kham from China. Therefore, Tsurphu Karmapa Rinpoché, the Mindröling regent Chung Rinpoché, and I were dispatched to visit the monasteries of our respective religious traditions in southern Kham — Dergé, Nyakrong, and so on — as personal emissaries of His Holiness. Monastic official Ngöshiwa Thupten Samchok, physician monk Loden Chödrak, and Dzemé Rinpoché, representative of the three seats, were sent as my guides and assistants. As we were the first to be leaving China for Tibet — bearing portraits of His Holiness, his letters, and funds to make offerings at the monasteries — I requested permission to leave early and left with my attendants Lhabu, Palden, and Losang Sherap. On the day I left, I had an audience with His Holiness to take my leave. As I was to travel a great distance for a long time, I saw that His Holiness was sad. I also felt quite sad to take leave of His Holiness, as I had been with him for a long time. At the same time, I felt a great relief to be free from China. His Holiness would visit Tsongön province, Tashi Khyil, and Kumbum and arrive in Chamdo through Chengdu and Dartsedo. I was to join his entourage in Chamdo after visiting Lithang, Chatreng, Ba, and so on.

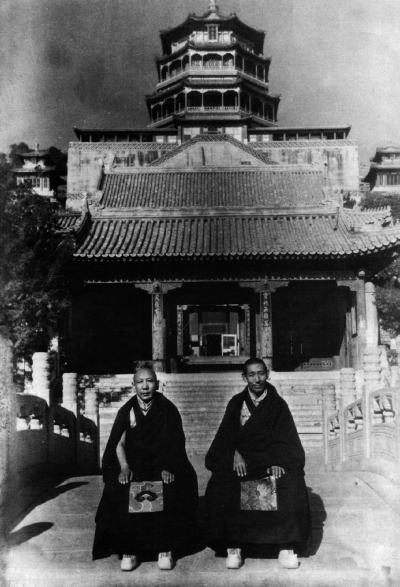

The two tutors in front of the Foxiang Ge (Pavilion of the Buddha’s Fragrance) at the Yiheyuan (Summer Palace) in Beijing, 1954

COURTESY OF YONGZIN LINGTSANG LABRANG

I then went to Beijing, where I spent a few days at the Bureau of the Dalai Lama. Karmapa Rinpoché, Mindröling Chung Rinpoché, and I went to visit the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché, who was staying in Beijing, and receive his blessing. At that time there was a Chinese man in Beijing named Yang Daguan who had received initiation into Kālacakra from the previous Paṇchen Rinpoché and the initiations of the Mitra Hundred,237 the Vajrāvalī, and so on from Ngakchen Rinpoché. As he was an observant Buddhist and requested, I secretly gave the blessing of the four sindūra initiations of Vajrayoginī to a group of about ten Chinese men and women who practiced Vajrayoginī. The important points of the visualization were translated into Chinese and explained. When we made offerings at the conclusion of the blessing, the Chinese melodiously chanted the offering and dedication prayers composed by Lama Vajradhara using Chinese phonetics. The main tsok offering was presented by two Chinese women, and they recited the verses by heart.238 Yang Daguan placed some offerings of incense and flowers before me and said, “In the past, when I possessed great wealth, I was a patron of Ngakchen Rinpoché of Tashi Lhunpo. I requested the Mitra Hundred and made a great offering. Nowadays, since my wealth is diminished, I am unable to make such great offerings.”

From Beijing, I traveled with Karmapa Rinpoché and others in a group. Traveling four or five days by boat up the Yangtze River from a city called Hankou to Chongqing, and by train in stages from Chongqing to Chengdu and Yangan, we arrived back in Tibet at Dartsedo. Representatives of Chatreng’s lay and ordained populations were there in Yangan and Dartsedo, along with my attendants Losang Yeshé and Namdröl, to receive us. I gave a long-life initiation and brief teachings on the Foundation of All Good Qualities at Ngachö Monastery in Dartsedo.

At Dartsedo I celebrated Tibetan New Year of the wood-sheep (1955), my fifty-fifth year. At the request of Gyapön Döndrup Namgyal and Chözé Ngawang Dorjé, I offered permission for Avalokiteśvara Who Liberates from All Lower Realms239 to about a hundred monks and laypeople in Dartsedo. When we arrived in Minyak, Karmapa Rinpoché and his retinue went to Dergé, and Mindröling Chung Rinpoché went to the Nyakrong. My retinue and I went to Ba and Lithang. As there were no motorable roads from that point on, we traveled solely on horseback from there to Chamdo.

There was a monastery called Kyilek in Minyak. According to oral accounts, my predecessor visited the monastery and gave teachings there for a few months. At the request of the administrators of the monastery, I paid a brief visit to make a token offering and give a teaching. From Minyak Rangakha, my attendants and I, Dzemé Rinpoché, the monk official representing the government, and the physician monk traveled on horses provided by the people of Chatreng. In addition to the Tibetan members of the entourage, twenty or so Chinese officers and soldiers joined us, ostensibly for our “security” but actually to spy on my activities. We did not want to bring them, but they insisted.

We crossed the Nyakchu River, and as we gradually made our way toward Lithang, we visited the family of Otok Sumpa and monasteries on the way and spent a night camping in the plains on the border of Lithang. Since the embodiment of sutra and tantra Song Rinpoché of Ganden Shartsé had been staying in Chatreng for a few years in my stead, he and Lakak Tulku came to greet me with a large number of horsemen on behalf of the monastics and laypeople of Chatreng. The following day, traveling together with the escort from Chatreng, I arrived at the great Lithang Monastery. I was received at a reception in a tent set up at the base of a nearby mountain. All the incarnate lamas and administrators in their best robes met us, and when we arrived together at Thupchen Chökhor Ling, the great monastery of Lithang, the line of escorts stretched out like a golden thread.

Arrangements had been made for me to stay on the top floor of Shiwa House, where I spent a few days and presented the offerings from His Holiness to about three thousand monks along with a portrait of His Holiness for their veneration. I also made my own offerings to the monks and at the Thupchen temple. At the request of the monastery I gave the initiation of the Great Compassionate One in the Lakṣmī tradition and an oral transmission and explanation of the Foundation of All Good Qualities to the monks and others in the courtyard of the assembly hall of the monastery. At their request, I visited various houses, including Chatreng House, and the family of the Seventh Dalai Lama in the main town of Lithang and performed consecrations and gave teachings according to their wishes. On the fifteenth of the first month, they had made excellent offerings [of butter sculptures] for the Prayer Festival at the monastery; I made dedication prayers along with the offerings, which were like a mass of clouds.

From Lithang we crossed Drakar Pass and, passing through Tsosum, offered whatever Dharma teachings and consecrations were requested at various monasteries, such as Jaja Nunnery. An escort arrived from Yangteng Monastery in Dap, so we proceeded to the monastery. There I presented offerings from the government and from myself. At the request of the monastery, I gave a permission of Avalokiteśvara Who Liberates from All Lower Realms and the oral transmission and explanation of the Foundation of All Good Qualities to the monks and local people. As Dzemé Rinpoché had not seen the monks and his parents and family for many years, they were all overjoyed when finally reunited there. I also met some prominent citizens of Dap, including Salha Dechen Chözin, with whom I shared a patron-priest relationship during my previous visit to Kham, as well as some other seniors with whom I had relations.

Along the way Pangphuk and Drukshö Monasteries, which had been places of practice for the First Karmapa Düsum Khyenpa, offered us a reception, so I visited each place. When I asked an aged abbot from Pangphuk Monastery about their religious traditions in the monastery and whether or not they kept up the “five sets of five” that had been the principal practice of the Jé Düsum Khyenpa, the omniscient one of the past, present, and future, it seemed that he had no knowledge of the five sets. I advised him that they should uphold their own traditions and that they should live up to the name of Jé Düsum Khyenpa. I was not sure whether he liked this, but I was very sincere in my advice.

A RETURN VISIT TO CHATRENG

Then after crossing Paldé Pass, we came to Upper Chatreng, where we spent two days in Chagong at the wishes of merchant Losang Yeshé at his home, called Thangteng Phakgetsang. I fulfilled the wishes of a large gathering with a Dharma teaching.

There, Gongtsen Karma Tsering, the wrathful spirit that was a local god in Chagong, suddenly possessed an oracle whose name in the local dialect was Moma. He said, “Well done!” and expressed how thankful he was, how happy he was for my recent visit to the region. When I was first recognized as an incarnate lama and later when I came to stay in Chatreng, the gods and men of Chagong didn’t accept my recognition at all. Now, although I cannot be certain whether I will achieve my aims in the next life, and I play like a child at life with the title of “tutor to the Dalai Lama,” a donkey draped in a leopard skin, all the people and the local deities exalt and pay respects to me. As they say, “Birds flock to the prosperous, but when you are destitute, your own son runs away.” Gods, spirits, and men all act the same, it seems to me, so I find this quite humorous.

While I was at Thangteng Phakgetsang, I met my very close friend Drodru Geshé Tenzin Trinlé, who was very learned and was in the class below mine at the monastery. We then traveled through Palgé, Sölwa, and many other towns, and I stopped briefly at the full reception of Samphel Ling Monastery at Ngechi Teng. Upon my arrival, the monks provided a grand feast of ceremonial cookies at which Song Rinpoché, Lakak Tulku, and the abbot and administrators of the monastery presented scarves to me. During the ceremony, Chaklek Geshé of Yarlamgang and Butsa Nakga Geshé performed what is called “the dialogue of the ceremonial feast” perfectly in the manner as it is done in Central Tibet.

Over the fifteen days that I stayed in my own room on the top floor of the assembly hall of the monastery, I made offerings of funds on behalf of the government to over a thousand monks and presented a portrait of His Holiness to the monastery. We also offered tea and funds from our own stores to the monks. At the request of the monastery and surrounding regions, I offered the initiation into the Great Compassionate One and an explanation of the Foundation of All Good Qualities to a massive audience of laypeople and monks.

In order to check the quality of the rituals of propitiations and the melodies of the prayers that I had restored and introduced during my previous visit many years ago, I summoned a group of about fifty chanters and dancers to the reception hall. One day I had them perform the ritual dance, and one day I had them perform the torma-casting ritual. On that day I had put on display the brocade appliqué thangka of the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita that I had previously sent from Lhasa and the appliqué thangka of Dharmarāja that is set out during the common sādhana, the torma-casting ritual, and enthronement ceremonies, and I tossed flowers to bless them.

On separate days I visited the newly constructed temples of Amitāyus and Jé Tsongkhapa and did the rituals of purification and consecration at each. They had established studies in dialectics at the temple of Jé Tsongkhapa, and thirty monks who were studying elementary dialectics debated for me. They were doing quite well, considering they were only beginners. One day a group of monks that Lakak Rinpoché had organized to perform the monthly appropriate offerings to Shukden performed the averting ritual together with its accompanying dance for me.

On another day, some of the principal monks and lay leaders from the four districts of Chatreng gathered in the reception hall to repent, from the bottom of their hearts, for breaching the guru-disciple relationship while obscured by partisanship and ignorance before when I was first recognized and when I lived in Chatreng. They asked forgiveness and promised that henceforth they would heed my advice concerning what to do and what to avoid. Asking that I love them like a mother loves a troubled child, they fervently begged me to accept their apology and care for them in all of their future lives.

In response I told them, “While it is true that each of you, layman and monk alike, have directly or indirectly entertained treacherous thoughts and actions in the past, not only have most of the principal offenders already passed, and the few that are still alive had a change of heart, since I personally bear the title ‘lama,’ it would go against my religious principles to hold a grudge and refuse to accept the apology of my adversaries when they hope to make amends. Since ‘rejecting the apologies of those who have wronged one’ contradicts the bodhisattva training, and all of you have restored your vows to perfect purity, like the sun emerging from behind the clouds, none of you need have any further misgivings.” I advised everyone to live in harmony: the monks to observe the monastic discipline and work to increase their spiritual activities and the laypeople in the community to uphold the noble ideals of human conduct.

A number of villages had urged me to visit, but because I needed to be able to meet His Holiness in Chamdo, I didn’t have much time, and so I gave up the idea of visiting each place individually. I arranged to meet the people from Trengshok at Chakragang, those from Rakshok at Rakmé, and those from Dongsum at Riknga Temple. After leaving the monastery, I spent one night at Chakragang Temple and gave a long-life initiation and teachings to the people from Trengshok. There I made offerings to and consecrated a statue of Karmapa Tongwa Dönden.240 Having met the people of northern Dongsum in the house of the Gongsum Shangmé family, I taught them Dharma. After that, I spent one night in Riknga Temple in Dongsum, where I also gave permission to practice Avalokiteśvara and taught Dharma. Then I spent one night at Rakmé Temple and gave teachings to the people of Upper and Lower Rakpo.

As I was returning from Rakmé I spent one night in the house of the Palri Yangdar family, where I met Gyalthang Abo Tulku Rinpoché, who had received many teachings from Kyabjé Vajradhara and myself. Having returned to his hometown, he had been giving extensive teachings including those on Jé Tsongkhapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path. This Rinpoché had come there especially to meet me, and we performed the tenth-day tsok together.

Over the period when I stayed in Chatreng, many of my closest friends traveled over long distances to visit me: for example, Venerable Sherap Rinpoché came from Gangkar Ling; Geshé Tenzin Chöphel, with whom I had studied under the same teacher before at the monastery, came from Mili; Gyal Khangtsé Tulku and Changowa Geshé Gyaltsen, who was the student who served our precious teacher, came from Nangsang; and Lawa Geshé Khunawa, tutor to Chamdo Shiwalha, came from Kongrak.

THE JOURNEY FROM CHATRENG TO CHAMDO

Mili Kyabgön Choktrul Rinpoché sent attendants bearing gifts and mules complete with saddles. Soon after that I left Chatreng with an escort of monks and laymen on horseback. After crossing the Makphak pass, we spent one night at Shokdruk Raktak Monastery where I gave a permission of Avalokiteśvara and teachings, and I consecrated the new temple dedicated to Jé Tsongkhapa. Then I visited Tongjung and Takshö and stayed in Datak Pakthang at the foothill of the snowbound Kabur region, the pilgrimage site of Heruka Cakrasaṃvara. The next morning, at their invitation, I visited Nego Monastery, where I made offerings to the monks and gave a permission of Four-Armed Avalokiteśvara to an audience of many monks and laypeople in their assembly hall.

Although I was unable to travel to the pilgrimage places due to heavy snowfall, I sent monastic official Samchok and Palden to do so and to visit Phawang Karlep, Kambur Drak, and so on to make offerings there. Nego Monastery offered me an antique thangka as an object of veneration, which I accepted. I gave them back the money and goods they offered me and supplied them with funds for making offerings to Cakrasaṃvara on the tenth of the month.

At Takpak Thang, at the request of Gyalthang Abo Rinpoché, I gave an initiation of Cakrasaṃvara body mandala combined with the preparation ritual in one day to Rinpoché himself along with Dzemé Rinpoché and Yangteng Khyenrap Tulku. The people of Ru region were lined up to receive us as we passed through Gemo Ruthok and so on, and most of the leaders of the monastery and its surrounding area, the abbots, monks, reincarnate lamas of Chödé Monastery, and so on came to escort us as we approached Lakha Hermitage in Ba. Then the monks of Chödé Lhundrup Rabten in Ba escorted us to the monastery, filing in a long line, and we stayed there in Lakha Labrang. At Chödé Monastery I offered His Holiness’s letter, photographs of him as objects of veneration, and monetary offerings on behalf of the government, and I made my personal offerings. At the request of the monastery and the local population, in the great field in front of the newly erected large Buddha temple, I gave an audience of monks, lamas, and local people the initiation into the Great Compassionate One.

After stopping off to teach and perform a consecration at Bawa Gyashok House at their request, we arrived at the great Drichu River via Chisung Gang. Having crossed the river on a log raft I met an escort of horsemen waiting on the bank, including Adruk, the treasurer of Gangkar Lama’s household, and others. We then passed through the village of Tarkha, the spot where our trader with horses and mules bearing merchandise were robbed together with those of the Palbar Tsang and Dampa Tsang households. After crossing Khangtsek Pass and traveling through Upper Bumpa, we arrived at Nyago Monastery in Bum. There, upon request, I gave a long-life initiation and teachings, including the oral transmission of the maṇi mantra.

After crossing the pass into Lower Bumpa and passing in stages through a valley called Gönang, we arrived at Gangkar Labrang at Seudru Monastery, where we were very well received and looked after for the three days we spent there. I taught Dharma to a large gathering of monks and laypeople from the monastery and its surrounding area, including giving permission to practice Avalokiteśvara Who Liberates from All Lower Realms and performed the consecration rite of Causing the Rain of Goodness to Fall for the memorial stupa of the late Gangkar Lama Rinpoché, which contains his fully preserved body that produces relics spontaneously. There is also a treasure box there containing what are called “immortal iron pills” that always miraculously replenished. There were always pills in the box until the lama passed his thoughts into peace, and thereafter they gradually diminished until the treasure box was empty. Just before the great lama passed away, for the sake of others he revealed a new treasure vessel of iron pills, shaped like an egg, but had not opened it. When I held the vessel in my hand and shook it, it sounded like there were many pills inside. The attendants of the lama asked me to open it, but I could not tell the top from the bottom. Baffled, I couldn’t figure out how to open it.

At Lhadun in Markham I visited the magnificent stone image of Vairocana reputed to have been carved by the Chinese queen.241 Passing through Gushö Pangda and so on, we stopped by Garthok Öser Monastery, Ribur Monastery, Kyungbum Lura Monastery, and others at their invitation. At each monastery I made offerings and gave teachings, oral transmissions, and initiations to satisfy their request. At the insistence of Drakpa Tulku and the denizens of Lura Monastery, I stayed there for three days. One day they put on a performance of the propitiatory ritual dance of the Seven Blazing Brothers that was said to be identical to the Demo Gucham ritual dance at Tengyé Ling in Lhasa. The moves with which the seven brothers of savage spirit Pawo Trobar of Laok blazed with a hundred expressions of wrath were magnificent and full of energy, and indeed they seemed remarkably like those used in the ritual dance at Tengyé Ling.

After a long journey, we reached the border of Drakgyab region. Drakgyab Labrang had sent a senior staff member to receive me there and assist us on the way. Excellent arrangements had been made at every place where we stopped. I was invited by the hermits of Sakar Hermitage to visit them, and although the monastery was out of our way and would take a long time to visit, because of my spiritual friendship with Lama Arap Rinpoché through our correspondence when he was still alive, I went there disregarding the inconvenience. I gave a teaching on the Foundation of All Good Qualities to the monks. They had recently established dialectical studies, and the students engaged in debate were quite good.

The day that I arrived at Bugön Monastery in Drakgyab, having been received by a great array of members from the labrang, a reception committee, and a long line of monks clad in yellow, I was housed in Dagyab Hothokthu Rinpoché’s quarters atop the assembly hall, where I stayed for four or five days. I gave the full assembly of monks the great initiation into thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava and gave the local public permission to practice Avalokiteśvara Who Liberates from All Lower Realms.

One day I visited the historically renowned Jamdun Temple to make elaborate offerings and do a brief consecration ritual. The principal image at Jamdun Temple was a wonderful stone image of Maitreya and his retinue that had emerged from the ground up. While I was staying at Bugön Monastery, a former classmate of mine named Geshé Bu Chögyal came from his hermitage to visit me. At the beginning of our meeting he assumed a very humble attitude and showed me much respect, but as we had long been spiritual friends, once I spoke casually with him about our experiences in the old days, the geshé also began to speak freely with me about the times we had shared and any news he had to offer, just as he had when we were in school together. I gave him and a few other earnest practitioners an outline of the main points, without detailed explanation, of the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita. Given the season over which I stayed, hardly any vegetables were available. So each day Drakgyab Labrang served me a tray with a variety of unique dishes prepared from the same type of meat, and I ate like the king of Lanka.242

From Drakgyab I reached the border of Chamdo, where Shiwalha Rinpoché, who was the general manager of Chamdo, monastic official Sönam Gyaltsen, who was the elder brother of Phakchen Rinpoché, and others had come to receive us there. We spent a night there, as had been arranged, and the next morning we went on to Chamdo Chökhor Jampaling Monastery, where we stopped briefly for an elaborate reception under a tent. Afterward we proceeded to the monastery on horseback in procession with many prominent members of the monastery and the region. Just on the other side of the bridge over the Dzachu River, there stood arranged in a line a vast welcoming party comprised of military and civilian masses, students, quite a few Tibetan officers and soldiers who had been captured by the Chinese when Chamdo fell, as well as government officials, abbots and representatives of the three seats, and public representatives who had all come there to receive His Holiness as he traveled back to Lhasa. After arriving at the monastery, I was made to feel quite at home in the residence of Shiwalha.

His Holiness’s arrival was briefly delayed because the motor route in the area of Dartsedo had been damaged by an earthquake, and so the large crowd was left waiting. In the meantime, at the heartfelt request of Shiwalha Rinpoché, I gave a discourse over the course of fourteen days on the stages of the path based on the Easy Path in the great assembly hall of Chamdo Monastery. The gathering numbered more than one thousand, including monks already living in Chamdo and those gathered there to receive and welcome His Holiness.

One day, at the invitation of Tsenyi Monastery, I gave a discourse in one session on the first few folios of the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to the monks in the debate courtyard. Then the students assembled in groups according to class level and began to debate. Thanks to the kindness of the great virtuous friend, Geshé Jampa Thayé Rinpoché, complete with the mandala of the ocean of learning, the dialectical studies were excellent, equal to the essence of dialectical studies in Sera Jé Monastery.

REUNITING WITH HIS HOLINESS AND RETURNING TO LHASA

When His Holiness arrived in Chamdo, I went to the other side of the bridge across the Dzachu River to greet him. When I saw his golden countenance, exceedingly meaningful to behold and radiating with ten thousand virtues and goodnesses, he regarded me with unrestrained warmth and gladness. Shortly afterward, when he had settled in his quarters, I went to meet him in person as he had requested. He shared with me in great detail general and specific news of his trip to different regions of China, his stay in the jurisdiction of Domé, how Mao Zedong’s way of speaking when he met with him made it clear his true intentions regarding Tibet, and many other things that I must keep secret within the innermost core of my heart. I too gave him a report of my travels to the different regions of Kham. This opportunity to pass the time at leisure with him refreshed the lotus of my heart with the rain of great pleasure and devotion, thus the petals of fortune unfolded. Shiwalha Rinpoché’s labrang took very good care of us throughout our stay in Chamdo.

I gave Rinpoché alone all the permissions of the seventeen emanations of Four-Faced Mahākāla except for Secret Accomplishment and Black Brahman,243 thereby fulfilling his wishes. Before I took my leave, he gave me a set of two ritual vases and inner offering cups complete with support and many other ritual objects made of gilded silver.

I left Chamdo with His Holiness and met Khargo Tulku, the general manager of Drakgyab Monastery, and others at Kyilthang in the territory of Drakgyab. Traveling in stages via Pangda in Tsawa, over the great bridge on the Gyamo River and so on, we came to Powo Tramo. A heavy rain had fallen the morning of the day we left Tramo, and boulders had spilled down the mountainside and blocked the road, holding us up for quite some time. The boulders were eventually cleared away so that the motor vehicles could just squeeze through.

Late in the afternoon just as the sun was setting, we came to a place where a waterfall from an overhanging ridge of the mountain came down in a violent torrent and had washed out one of the corner supports of the bridge we needed to cross. It was much too dangerous to cross the bridge in our vehicles, so His Holiness, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, myself, and a few other members of the entourage first crossed the bridge on foot, and then the cars were driven across one by one. Just as one of the vehicles was crossing the bridge, it gave out a loud cracking sound as the timber splintered. Although the bridge collapsed in half and plummeted down the ravine, no one was hurt, but the rest of our entourage and luggage were left on the other side of the river. The rest of us who had made it across piled into the few vehicles we had and traveled down the winding road through the night, terrified of gushing cataracts, precipices, and deep ravines, until we arrived at a place called Lunang in Kongpo around midnight.

There, without any bedding whatsoever, Losang Sherap and myself spent a cold night in a cloth tent. Mr. Mentöpa and a few government officials of the fourth rank had come there from Lhasa to receive us. I barely slept that night due to anxious worry about those left behind. That night Chinese road workers put a bridge across the river suspended on two logs bound together with ropes. His Holiness’s chamber attendant and a few members of his kitchen staff then crossed the bridge. Palden also joined them, at great risk to himself, out of concern for my safety and came in a jeep to join me at the break of dawn. Lhabu and Losang Yeshé were left behind and were unable to catch up with us until we arrived at Dakpa Monastery in Maldro.

Making our way in stages along the road through places in Kongpo, such as Demo, Nyangtri, and Gyada, we crossed Ba Pass to arrive at Dakpa Monastery in the district of Maldro, where members of Namgyal Monastery’s Phendé Lekshé Ling who had prepared lodgings for His Holiness awaited us. There we were received by the estate manager of Maldro Jarado and Lhakchung from our house in Lhasa.

At the foot of Ganden I lunched together with His Holiness’s entourage in a meadow as lush and green as a parrot’s wings outstretched, where the governing body of Drok Riwoché Ganden Nampar Gyalwai Ling had prepared an elaborate reception in a tent. After meeting with the abbots, incarnate lamas, and monastic administrators, I went on to the temple at Tsal Gungthang, my birthplace. Every government official, of high, middling, and lower ranks, lay and ordained, and a great number of abbots and incarnate lamas from the seats of Sera and Drepung monasteries had arrived there to greet His Holiness. The government offered an elaborate welcoming feast of cookies in the temple, and Gungthang Labrang offered a separate feast in the sunlight room atop the temple. I, too, remained at Gungthang for three days, awaiting the astrologically auspicious day for the party to travel to Lhasa.

Around the thirteenth day of the fifth month, His Holiness traveled by sedan chair from Gungthang to the Norbulingka Kalsang Palace with an elaborate, traditional procession of riders on horseback. Since it rained heavily that day from the moment the procession departed Gungthang until it reached the Norbulingka, the sedan chair had to be draped with a rainproof cover, and all the members of the entourage had to wear red woolen rain capes over their best ceremonial attire. It occurred to many of us that this was not a good omen. After the reception ceremony upon our arrival at the Norbulingka, I returned to my house in Lhasa, where over the course of many days patrons and students of all levels with whom I bore religious and secular connections visited, and I accepted their offerings, which were as abundant as the cloud formations.