CHINESE APPOINTMENTS AND MY MOTHER’S PASSING

THAT YEAR, the Chinese asked me to be the principal of the Lhasa middle school. I declined, citing my lack of experience of the modern educational system so that my services would be of no benefit. The Chinese appealed to His Holiness, and I was forced to accept the position. I would go to visit the school once a week to offer my thoughts and advice to the teachers and students.

In the fall, as requested by Phakchen Hothokthu of Chamdo, I gave the complete permission of the Rinjung Hundred practice in the assembly hall of Shidé Monastery to a gathering of over three thousand including Phakchen Rinpoché, Dagyab Hothokthu, the incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara, as well as to many lamas, geshés, and monks of the three monasteries and others. As gifts for my safe return from China, I made many offerings and monetary donations for annual offerings to the three seats and the two tantric colleges. I presented Shartsé College of Ganden eight large decorative banners made of Varanasi brocade for the eight tall pillars in their assembly hall and presented Dokhang House four large pillar banners of Japanese brocade and a victory banner along with three triangular banners.

In my fifty-sixth year, the year of the fire-monkey (1956), my mother Tsering Drölma passed away at the venerable age of eighty-two after being treated for a sudden illness that lasted a few days. I had visited her often before and at the time of her death on the twelfth day of the first month, giving her advice on virtuous thoughts. Afterward I whispered the names of the tathāgatas and various types of profound dhāraṇī and mantras in her ear and then performed with care the ritual for transference of consciousness. Although my mother did not know many different practices, she was kind at heart, regularly recited the six-syllable mantra, and made great efforts to perform virtuous practices with her body and speech by doing prostrations and making offerings at the inner and outer courts of the Tsuklakhang and by circumambulating Lhasa’s circular path. So she suffered not even the slightest pain from her sickness nor experienced any hopes or fears based on clinging when she died but passed from life peacefully in her sleep just as a lamp dies out when its fuel is exhausted. Since Lhasa’s Great Prayer Festival was in session at the time, I made offerings on the fifteenth of the month and made offerings at various monasteries each week thereafter.

An official called Marshal Chen Yi came from China to inaugurate the Preparatory Committee for the Autonomous Region of Tibet that would be comprised of fifty-one representatives drawn from three areas: the government, Tashi Lhunpo, and the three regions including Chamdo. Again, I was required to join that committee against my will. And, again, although I had no desire to do so, I was forced to accept the title of director in an office called the Bureau of Religious Affairs. However, when the bureau actually began its work, no matter what suggestions I made, sitting at the head at the table, they did not influence matters. All the major decisions were inevitably made according to the wishes of Hui Khochang, the Chinese member. My appointment to the position of principal at the middle school was also in reality devoid of any power. My being powerless while forced against my will to bear empty civilian titles that I had no appetite for was punishment visited upon me due to past acts, such as giving Dharma talks that were mere words delivered without having practiced them myself — a grand dance to allure the faithful into the drama of the eight worldly concerns. As Mañjunātha Sakya Paṇḍita said in his Jewel Treasury of Wise Sayings (8.29):

If a monkey did not dance,

would it still be leashed at the neck?

And also (6.36):

Because the parrot speaks, he is put in a cage,

while the mute bird flies free.

When these meetings actually began in the fourth Tibetan month, both His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché were required to attend them in full, and a great many representatives from the provinces of China, Amdo, Inner Mongolia, and from Kham and its regions attended. The assembly was convened with a great celebration, and afterward many days were passed with the distracting tumult.

In the sixth month at the request of the monk Gendun Chöyang, a family member of Rong Dekyi, I gave over the course of a few days initiation into Cittamaṇi Tārā according to the close transmission lineage stemming from the divine visions of Takphu Vajradhara and gave an explanation of the two stages to nearly one thousand disciples, lamas, reincarnate masters, geshés, and so on in Shidé assembly hall. After that, at the request of Dagyab Hothokthu Rinpoché, at Shidé monastic college I offered an audience of more than one thousand the great initiation of Secret Hayagrīva in the Kyergang tradition along with its preparatory practices. Right after that I offered in a series: permissions to practice the Surka Cycle of sādhanas, the eighty mahāsiddhas, and the deities of the sādhana cycles taught by Gyalwa Gendun Gyatso; four transmissions and their blessings including the distant lineage of the long-life initiation of Amitāyus, two close lineages of Drigung Chödrak’s vision, and the exclusive long-life empowerment for Amitāyus as a single deity with a single vase in the tradition of Machik Drupai Gyalmo; and permission for Bhagavan Samayavajra along with permissions for the collected mantras of Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava.

VISIT TO RADRENG

In the eighth month, at the invitation of Radreng Labrang, His Holiness, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, and myself traveled to Radreng Gephel Ling with a small entourage, proceeding from the Norbulingka along the northern motor roads through Tölung and Damshung. His Holiness presided over the full ritual of consecration in the main temple, which we performed over a three-day period. There we saw sacred relics such as the statue of Jowo Jampal Dorjé, the reliquary stupa of Atiśa, his monastic robes and saṅghāṭi,244 his personal volumes of Indian texts, Dromtönpa’s personal copy of the Eight Thousand Verse Perfection of Wisdom, the statue of “left-leaning” Atiśa, and the thangka of Vajrabhairava that was Guru Dharmarakṣita’s principal object of meditation.

The room I stayed in was the room in which I had previously received novice ordination. Among the many texts housed in the room I found a hand-copied commentary on Asaṅga’s Compendium of Abhidharma that the venerable Rendawa had composed at the request of Jé Tsongkhapa himself245 and a volume of various collected teachings of Rendawa. As the commentary on the Compendium was exceedingly detailed, I fell asleep over it with my head swimming. The next day among the texts I found a few handwritten letters exchanged between Jé Tsongkhapa and Rendawa on matters of sutra and tantra in general and on the view of emptiness in particular. These letters were separate from the ones found in the collected works of Jé Tsongkhapa. I wanted to transcribe them but found no time, and so I wanted to borrow them and take them to Lhasa, but we were constantly distracted and the time passed. It was unfortunate, but it could not be helped. At Yangön Retreat Monastery, the site where the noble lord had composed the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path, His Holiness and we his entourage read aloud the Great Treatise, dividing its sections among us.

Earlier when the prior regent Radreng Rinpoché and his followers fell from power in the year of the fire-pig (1947), soldiers had peeled the silver covering the reliquary stupa and had pried the jewel ornaments from the stupa and statues. They had been pockmarked with bullet holes. A three-dimensional mandala of Guhyasamāja had been smashed to pieces with cudgels like an earthen clod. When I saw the mounds of ruins and so on — evidence of the many wicked, nearly inexpiable acts, more degenerate than those of the degenerate era, that had been carried out — and thought about this special, sacred place that is the headwaters of the Kadam teachings having fallen into this state of deterioration, I was stricken with grief. With Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché acting as the preceptor and I as the master, the supreme incarnation of Radreng Rinpoché received novice ordination.

On the return journey, at the request of the renowned Gyümé Monastery, treasury of the profound tantras, which was observing the late rainy-season retreat in the valley of Chumik in Tölung, His Holiness stopped there to create a Dharma connection with the monks. By traveling there together with him, I was able to see the sacred thangkas of Jé Sherap Sengé246 that Jé Tsongkhapa had given him. Following my return from Tölung, I went and participated in the annual consecration rituals at the invitation of Ganden Shartsé. One day I offered an explanation of the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita to most of the monks of Shartsé and Jangtsé in the debate courtyard of Shartsé.

CELEBRATING THE BUDDHA JAYANTI IN BODHGAYA

That year (1956), His Holiness and the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché were one after the other both extended invitations to the festival that the Mahabodhi Society in India had organized to commemorate the two thousand five hundredth anniversary of the mahāparinirvāṇa, or passing, of Lord Buddha (according to the Theravāda tradition). Although they both really wanted to attend, the Chinese, using various excuses, indicated that it wouldn’t be good for His Holiness to go and asked that he send a representative instead.

His Holiness appointed me to the task, with Dzasak Khemé Sönam Wangdü and monk official Ngöshiwa Thupten Samchok as assistant liaisons and Rinchen Sadutshang as our interpreter.247 On the day that we visited him to take our leave for the trip to India, Zhang Jingwu, the Chinese representative in Lhasa, came to inform His Holiness that he had received a telegram from China saying that it was all right for him to attend the religious festival in India. It had suddenly been resolved. I was told that it was necessary that I still accompany him in his entourage, and soon after His Holiness, Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, myself, cabinet minister Ngaphö, and so on left Lhasa with a small entourage.

We traveled along the Ü-Tsang motor road through Tölung and Uyuk to Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, where after having met with the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché, we passed one night.

Lord Chamberlain Phalha Thupten Öden had earnestly requested that Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and myself spend a night at Paljor Lhundrup, his family estate in Gyantsé. So as soon as we finished paying our respects to Paṇchen Rinpoché at Tashi Lhunpo, we set out for Paljor Lhunpo, arriving at eleven o’clock that night. Although I had gone that way to Gyantsé before, due to the blackness of that moonless night, I couldn’t make out the road. Not only did Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and his entourage not know the way, neither did the Chinese driver! Because we were going along based on guesswork, we were all terrified of plummeting over the edge of a cliff — we all got a little taste of the first noble truth, the truth of suffering!

We went from Gyantsé to Jema in Lower Dromo in one day. The next morning we joined the entourage of His Holiness at Nathu Pass. The two supreme victors, spiritual father and son, traveled in a single group. Several Chinese officers and soldiers came to accompany them up to the top of the pass. Beyond it at the frontier, they were greeted by an Indian guard of honor and the representative of the Indian government. Passing Tsogo Lake we reached Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim, where we were received in the palace of the maharaja.

The next morning before dawn we left for the airport in Siliguri by car and boarded a special plane. That evening we touched down in the capital, New Delhi, where we were received by a large welcoming committee — including the vice president,248 Prime Minister Nehru, members of the diplomatic corps, and leaders of the delegations who had come to attend the celebrations. His Holiness and his entourage stayed at Hyderabad House, a guesthouse for important foreign dignitaries. Tutor Ling Rinpoché and I stayed in the rooms adjacent to His Holiness’s suite.

The following morning I went together with His Holiness and Paṇchen Rinpoché to visit Raj Ghat, the memorial place where Mahatma Gandhi was cremated. Over the next several days I was a part of the entourage that participated in the ceremonies of the Buddha Jayanti. My kind spiritual friend, that fearless lion-like exponent of the teachings, Geshé Sherap Gyatso of Lubum, who had also come from China as one of the delegates to the Jayanti, was staying at the Ashoka Hotel in Delhi. I went to pay my respects to him and he contented my heart with a stream of his ever-nourishing words of wisdom.

After the great Jayanti ceremonies were completed, I accompanied His Holiness as we toured the major sites of Buddhist pilgrimage as the guests of the government of India. We visited sites such as Bodhgaya, Varanasi, Nālandā, Kushinagar, Lumbini, Vulture Peak, Sanchi, and the Ajanta caves and Nagarjunakonda in South India, cities such as Bombay, Mysore, Bangalore, and Calcutta, and we toured some major industrial plants. When I visited holy sites like Nālandā, I thought about how the compassionate Buddha and the Six Ornaments and Two Excellent Ones249 had done this and that at this specific place, and remembering the stories of their lives, was filled with faith. I was also happy to have been able to go to those places, but since little more than ruins remain of them now, I felt sad. Reflecting on impermanence, I was torn between equal feelings of faith, joy, and mourning.

Earlier in China and now in India we toured many industrial factories. As I watched molten iron and copper, cascading like rivers, being poured into molds and pressed out and beaten by massive machines, I was reminded of the torments of the hell realms, and a healthy sense of urgency would well up in me. Nevertheless, after a few days the scattered thoughts of one who has grown callous to Dharma would return anew. The fact that I was unable to wholly rid myself of the habitual undercurrent of thoughts governed by the three poisons indicates just how ingrained are the predispositions to bad behavior I have acquired through prior lifetimes.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the two tutors, and the rest of the official entourage at Hyderabad House in New Delhi, India, 1956

COURTESY OF OFFICE OF HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA

FEARS AND CONFLICT UPON RETURNING TO TIBET

After staying in Kalimpong for several days giving Dharma discourses and so on, His Holiness went to Gangtok. Prime Minister Dekhar Tsewang Rabten (Lukhangwa), deputy cabinet minister Yuthok Tashi Döndrup, and monk official Ngawang Döndrup had arrived there from Lhasa under the pretense of escorting His Holiness back to Tibet, but in fact they had come first and foremost to report to him about the deteriorating conditions and the forceful occupation by the Chinese. As they implored him that it would be best to remain within India, about half a month passed without resolving the issue of whether to return or to stay. I stayed in Kalimpong at the house of the Sadutshang family.

All-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché and his entourage had already left Kalimpong for Tsang ahead of us. As soon as it had been decided that His Holiness would return to Tibet, I reported to Gangtok and we all departed as a group. When we reached the top of Nathu Pass and I saw the flag of the Chinese officers and soldiers who had come to receive us, I felt great sorrow and trepidation, like someone being returned to prison.

Traveling in stages on the road through Dromo and Phakri we arrived in Gyantsé. It so happened that the new year of the fire-bird (1957) came when we were in Gyantsé, so His Holiness and the entourage spent a few days there. It was arranged that I would stay at Shiné Monastery. I fulfilled the wishes of Shiné and Rikha250 monasteries with teachings on the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita and the Foundation of All Good Qualities, among others. On the twenty-ninth day of the twelfth month, Shiné Monastery performed a torma-casting ritual dance for His Holiness. I thought it was a good presentation and not performed merely to satisfy the shopkeepers. There was a New Year celebration with ceremonial cookies arranged by the government. At the celebration, Dzemé Rinpoché of Shartsé and Ratö Khyongla Rinpoché performed the religious dialogues.

Following New Year’s, His Holiness traveled to the headquarters of the Samdrup Tsé district via Panam, where we also stayed. The population of the thirteen counties under the administration of the Tsang central government, both the upper and lower classes, offered a long-life ceremony for His Holiness, and His Holiness offered the public Dharma teachings in the district assembly hall.

Moving to the great Dharma seat of Tashi Lhunpo, His Holiness reunited with the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché. He visited temples, made offerings, and consecrated images. After delivering Dharma teachings in the great assembly halls at Tashi Lhunpo and the Dechen Phodrang Palace, I was fortunate to travel together with His Holiness as he toured Ngor Evaṃ Chödé, Pal Narthang, Shalu, and Rithil and the temple of Shalu Gyangong, the place where Mañjunātha Sakya Paṇḍita took his vows of full ordination before the Kashmiri paṇḍita.251 I was quite fortunate to have had that opportunity.

All throughout the time that His Holiness stayed at Tashi Lhunpo, the administration of Tashi Lhunpo had arranged for me to stay at Pontsang Drangkhang, which was the home of the tutor Lhopa Tulku Rinpoché. Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and I had an audience with the all-seeing Paṇchen Rinpoché. We offered him gifts and money during a visit filled with cordial conversation. Afterward, I also visited tutor Ngulchu Rinpoché, who had invited me because in the past he received from me the oral transmission of the collected works of Jé Tsongkhapa and his two disciples.

The two supreme victors, spiritual father and son, inwardly shared the same view of things and were in fact quite close to one another, harboring not even the least bit of tension between them. Since this was the case, with the hope of further strengthening goodwill between the Ganden Phodrang government and Tashi Lhunpo — a profound connection based on pure, unsullied vows — I expressed my sincere, unvarnished opinion to many of the key figures on the staff of Tashi Lhunpo on various occasions, such as when Paṇchen Rinpoché first came to Lhasa from Amdo and during this visit. But it was as in the proverb “Profound Dharma brings powerful evils.”252 On the one hand, the Chinese were using various deceitful means to sow dissent in Tibet, and on the other hand, some officials both in the government and Tashi Lhunpo, their minds influenced by devils, were eager to cause schisms between the two lamas. The situation was fraught. It seemed as though Khardo Rikzin Chökyi Dorjé’s prophecy had come to pass:

The skein of wool of Ü and Tsang

has been shredded by insects over many years and ruined.

Still, in hopes of weaving fine, smooth cloth,

you wear yourselves out searching for a weaver.

Departing Shigatsé by way of the Tak ferry, I accompanied His Holiness on a tour of monasteries he had been invited to, such as Ganden Chökhor Monastery in Shang, Dechen Rabgyé Ling, Thupten Serdokchen Monastery, the seat of Paṇchen Shākya Chokden, and Yangchen Monastery in Tölung, until his lotus feet once again graced the grounds of the Norbulingka Palace in Lhasa.

At the request of Drip Tsechok Ling Labrang, over the course of at least twenty-five days during the fourth month, I taught the root verses of the Guru Puja and Kachen Yeshé Gyaltsen’s great instruction manual on it, along with instructions based on the root commentary on Ganden Mahāmudrā by Paṇchen Losang Chögyen.253 The audience of around eight hundred included lamas, reincarnate masters, and geshés who had come from Sera, Drepung, and Lhasa, such as Dagyab Rinpoché and the incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha Rinpoché. The discourse sowed roots of virtue with meaningful exposition.

VISITS TO TSURPHU AND YERPA

At the invitation of Tsurphu Karmapa Rinpoché, supreme holder of the lineage of siddhas, His Holiness visited Tsurphu Monastery in Tölung. Tutor Ling Rinpoché and I accompanied His Holiness, and we were all well received. There I saw such things as the central statue called the Great Sage that Ornaments the World, which was miraculously erected by the Second Karmapa Karma Pakshi, and the memorial stupa of the First Karmapa Düsum Khyenpa called Tashi Öbar.

On the tenth day of the fifth month, we experienced the spectacle that was the festival famed as the Tsurphu Summer Dances. It included the ritual dance of the eight aspects of Guru Rinpoché, performed with graceful and relaxed movements, and Karmapa Rinpoché himself led the ritual dance of the ḍākas and ḍākīnis. One day while we were there, when the great relic boxes of Tsurphu Labrang were opened for His Holiness to see, I was lucky enough to see the various relics of the golden lineage of Kagyü gurus and of many other Indian and Tibetan paṇḍits and siddhas, the black hat with golden ornament on the front, and so on.

When the Fifth Karmapa Deshin Shekpa (1384–1415) traveled to China to perform funeral rites on behalf of the Yongle emperor (1360–1424), from the fifth day until the nineteenth of the third month of the fire-pig year (1407), people witnessed rainbow-tinged clouds in various shapes, such as elephants and lions, in the sky and saw buddhas, bodhisattvas, and celestial offerings among the clouds. On the final day a golden light spread from the west throughout the entire Chinese empire. I was shown the large silk scroll, mentioned in Pawo Tsuklak Trengwa’s religious history, on which, at the orders of the Yongle emperor, the many wonders that appeared were captured each day in paintings accompanied by inscriptions in Tibetan, Chinese, and Uyghur scripts. It was an excellent piece of art in the ancient Chinese tradition. The miraculous signs and good omens that appeared at that time filled me with a wonderful joy that increased my faith and belief.

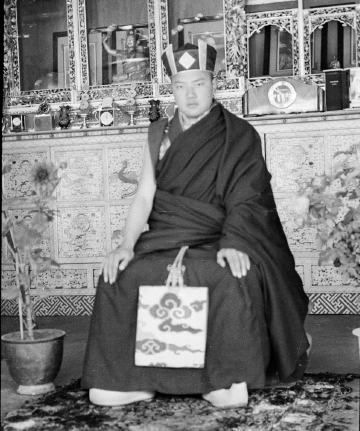

The Sixteenth Karmapa Rangjung Rikpé Dorjé at Tsurphu Monastery, 1946

© HUGH RICHARDSON, PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD; 2001.59.7.36.1

On the way back from Tsurphu, I accompanied His Holiness when he stopped by Nenang Monastery at the invitation of Pawo Rinpoché. We visited the memorial stupas of Tokden Drakpa Sengé (1283–1349)254 and others and then returned to Lhasa.

In the eighth month, after the rainy-season retreat at the Norbulingka Palace, His Holiness visited the holy site of Drak Yerpa and stayed on the top floor of the assembly hall of Ganden Sang-ngak Yangtsé at Yerpa Monastery. I also roomed there and saw, among other things, Lord Atiśa’s plate that bore an image of himself that he had drawn. At the time the monks of Gyütö Tantric College, the assembly of those who practice the secret tantra, were in the middle of their later rainy-season retreat. Together with the entire assembly of monks, I participated in the Guhyasamāja ritual of consecration for three days. His Holiness presided over this ritual of causing extensive blessings of vajra wisdom to descend on behalf of the world and the living beings supported within it. We also visited and made offerings to the large Maitreya statue that Matön Chökyi Jungné erected in the Maitreya temple, the statue of Avalokiteśvara that Rigzin Kumara made in Songtsen Cave, a statue of Vairocana dating back to the time of King Songtsen Gampo, the protector chapel of Palden Lhamo, the cave in which Lhalung Paldor255 practiced, the Tendrel Phuk Cave of Atiśa, and the temple of Prince Gungri Gungtsen. Tsok offerings were made in the room, called Moon Cave, of Orgyen Padmasambhava, the second Buddha.

At the joint request of Gyütö Tantric College and Yerpa Monastery, His Holiness, himself an emanation of Dromtönpa, read Atiśa’s Lamp on the Path to Enlightenment as an oral transmission to a great crowd of people gathered on the slopes of Yerpa Lhari Nyingpo. I was delighted and extremely fortunate to have been together with His Holiness when he graced the Dharma and living beings with great happiness and benefit on the very same holy spot where earlier Lord Atiśa and his spiritual sons had lit the lamp of the Kadam sevenfold divinity and teaching.256

After His Holiness completed his activities at Yerpa, we stopped off at Garpa Hermitage on the way back to Lhasa at the request of the all-embracing lord of a hundred buddha families, Kyabjé Ling Vajradhara. Passing just three or four days there receiving offerings of long-life prayers and consecrating images, His Holiness left ahead of us. Rinpoché said to me, “Stay and relax for a few days.” So together we passed some time relaxing and having deep and wide-ranging discussions with one another and then returned to the Norbulingka.

After that, at the request of Lady Dorjé Yudrön of Yuthok Kyitsal, over the course of a month in the assembly hall of Lhasa’s Shidé Monastery, to an audience of more than four thousand ordained sangha members, chief among whom were nearly fifty incarnate lamas of various ranks, such as the supreme incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara, Dagyab Hothokthu, and Chamdo Phakchen Hothokthu, and many well-known geshés like the former Sera Jé abbot Tsangpa Thapkhé, I gave the last teachings on the stages of the path I would give in Tibet. I explained, based on personal experience, the Quick Path and the Easy Path, the Words of Mañjuśrī according to both the central and southern lineages, and Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand based on my notes. In addition I taught the Seven-Point Mind Training and the sections from the stages of the path on equalizing and exchanging self with others, concluding with the ritual to develop bodhicitta.

After that, at the request of the exponent of the vast scriptures Geshé Ugyen Tseten from Sera Jé’s Trehor House, I went to Sera and in the debate courtyard of Trehor House offered an extensive teaching on the Hundred Deities of Tuṣita to a large group of monks that included the supreme incarnation of Radreng Rinpoché, incumbent and retired abbots of the Jé, Mé, and Ngakpa colleges, and other lamas and geshés.

In my fifty-eighth year, the year of the earth-dog (1958), at the request of the supreme incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha Vajradhara, I gave teachings on the close lineage of the cycle of Mañjuśrī teachings that was transmitted to Jé Tsongkhapa by Mañjuśrī himself, the Thirteen Golden Dharmas lineage exclusive to the Sakya tradition, the permissions of the Thirteen Divine Visions of Takphu, and oral transmissions of the above teachings to an exclusive group of monks and lamas including the supreme incarnation of Kyabjé Phabongkha at his residence in Lhasa.

HIS HOLINESS’S GESHÉ EXAMINATIONS

During the sixth month, I went along with His Holiness, our supreme refuge and protector, when he made the trip to Drepung Monastery, as he was required by custom to visit the three seats upon the successful completion of his intensive study of the five great treatises.257 I stayed with His Holiness on the upper floors of Kungarawa Palace, as had been arranged.

His Holiness stood for his geshé examination in the main courtyard of the great assembly hall amid an ocean-like assembly of intelligent and spiritually liberated monks, preceded by recitation of the verses of homage and his initial dissertation. After responding firmly and without hesitation to the challenges regarding the thornier points of the five great treatises that were mounted by the abbots of Drepung and high-ranking geshés who were well versed in the art of dialectics, His Holiness presented challenges to the abbots of Gomang and Loseling, shining a light of eloquent explanation that delighted the learned. On the same visit, he attended a grand feast of ceremonial cookies that the governing body of Drepung offered in the great assembly hall, forged a Dharma connection with the whole assembly by teaching them Dharma, and consecrated and purified the four cardinal points of the circumambulation circuit while circumambulating Drepung with his full entourage. Tutor Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, who was Sharpa Chöjé, and his labrang made offerings of food and funds to the monks in Drepung’s assembly hall, and His Holiness was invited to bless the occasion with his presence.

I was very fortunate to accompany His Holiness to various celebrations, as when he taught Dharma in the Sang-ngak Gatsal assembly hall of Namgyal Monastery at the request of the Namgyal monks. At the end of the official functions at Drepung, the government also made elaborate and generous offerings of food and funds in the assembly hall during the religious ceremonies connected with the examination.

Afterward, His Holiness visited Nechung Monastery, which was on the way back. The great Dharmarāja, through his medium in trance, came to the staircase under the western gate, respectfully bowed to His Holiness, and led him by the hand to the assembly hall, where he respectfully offered him a seat. There the monastery offered a feast of ceremonial cookies, and the Dharma protector showed us treasured ritual objects, like the Sebak Mukchung mask. Then the oracle summoned the cabinet ministers to join His Holiness, Tutor Ling Rinpoché, and myself and offered prophecies concerning religious and political life, saying things like, “There is the danger that a time may come when we are without a leader!” When he made these prophecies, I and everyone else feared that they foretold circumstances hostile to His Holiness’s life. Later, after we had come to India, we understood that it must have referred to our country of Tibet being left protectorless.

Then I accompanied His Holiness to the great center of learning Sera Monastery, where he stood for his geshé examination, taught the Dharma, and was offered a great feast of ceremonial cookies. The government also made an offering of funds equal to what they had done at Drepung. While staying at Denma House over the course of our visit to Sera, I paid a visit to the supreme incarnation of my supreme refuge, Phabongkha Vajradhara, and we shared a leisurely visit. Later, the supreme lord of victors successfully completed his official functions at Sera and returned to the Norbulingka Palace.

In the eighth month when His Holiness once again traveled to Ganden, he traveled by car from Lhasa to Tsangthok, in the Ganden foothills. On the way, he briefly stopped at Sang-ngak Khar Monastery at Dechen to pray for assistance before the principal image of the monastery, a Six-Arm Mahākāla statue that was consecrated by Khedrup Jé. His Holiness traveled from Tsangthok to Drok Riwoché Ganden Nampar Gyalwai Ling in an elaborate, traditional procession of riders on horseback. I once again stayed at my residence above the assembly hall of Dokhang House.

His Holiness had completed enrollment ceremonies at Drepung and Sera during the fire-pig year (1947), but the initial enrollment ceremonies at Ganden remained to be done. So enrollment ceremonies and geshé examination took place on that same occasion. His Holiness visited each of the colleges and attended a grand feast of ceremonial cookies. High-ranking scholars graciously presented challenges regarding the five treatises in the debate courtyard. As part of his examination, His Holiness presented challenges to the abbots of the colleges and then in turn responded to the questions they put forward. He forged a Dharma connection with each college by giving a Dharma discourse. The government offered elaborate offerings on this auspicious occasion at each of the colleges, and he attended a grand feast of ceremonial cookies that the governing body of Ganden offered in the monastery’s great assembly hall. He forged a Dharma connection with the whole assembly by teaching Dharma, and he stood for his geshé examination in the monastery’s great debate courtyard, just as he had done at Sera and Drebung. The labrang of the Ganden Throneholder offered a feast of ceremonial cookies in Yangpachen Temple, and the government offered a thousandfold offering and an elaborate tsok at Ganden’s sacred shrines, beginning with the great golden stupa of Lama Mañjunātha Tsongkhapa.

Over the course of two or three days, a massive assembly presided over by His Holiness that included the incumbent Ganden Throneholder Thupten Kunga, Sharpa Chöjé Ling Rinpoché, myself, the ritual assistants of Namgyal Monastery, the abbots of Shartsé and Jangtsé colleges, incarnate lamas, and geshés performed an elaborate purification ritual together with tsok in the Dharmarāja chapel as part of a consecration ritual associated with Vajrabhairava. During that time, my own labrang offered tea and sweet rice to the ocean-like assembly of intelligent and spiritually liberated monks gathered in the main assembly hall of Ganden, the most potent place of merit for gods and men. Each monk was offered fifteen sang in silver and a ceremonial scarf, and a fund of silver sang for annual offerings to the monks was established.

On the same occasion, I invited the great being who embodies the wisdom, compassion, and power of the entire sea of spiritual guides throughout the ten directions, the supreme all-knowing and all-seeing lord of victors, to sit atop the golden throne of the Mañjunātha king of Dharma Tsongkhapa. I began by describing the great qualities of His Holiness’s body, speech, and mind and then recited the mandala treatise and made extensive, substantial clouds of offerings to the extent of my merit, giving whatever actual money I had available. After the session in the assembly hall concluded, I graciously accepted gifts of appreciation for a job well done, which was offered by the government in the quarters above the assembly hall with a feast of ceremonial cookies.

One day, walking in an elaborate traditional procession with the full entourage, His Holiness consecrated and purified the four cardinal points of the circumambulation circuit and chanted prayers there. Stopping at the edge of the spring by the assembly hall, we chanted the prayers Eastern Snow Mountain258 and Sacred Ground, a praise of Ganden by His Holiness Kalsang Gyatso.259 Because Eastern Snow Mountain wasn’t among the traditional recitations at Namgyal Monastery and because of the clamor and chatter of the crowd of people who had gathered to catch a glimpse of His Holiness that day, some confusion arose halfway through the prayer. Although I began to grow anxious that the chanters would altogether lose the thread of the prayer in front of the crowd, the strength of the voices of those monks who were skilled at chant dominated with a light and melodious tone that concealed the underlying discord, and we successfully made it to the end of the prayer.

One day, I accompanied His Holiness, who was mounted on a white yak, as he rode with a small entourage to the top of Wangkur Hill. There we performed an extensive incense offering260 and praises to the local mountain deities.261 Looking down from the top of the hill at Ganden spread out below, I thought of the kindness of our spiritual father Jé Tsongkhapa and his descendants and of my time in the monastery studying and taking part in the Dharma assembly. I was overcome with wistfulness and joy in equal measure.

Once during our visit, the monastery opened a sealed chest of sacred relics housed in the Throneholder’s residence and showed us Jé Rinpoché’s very own upper garment, his set of three monastic robes, and many other important relics, and small portions of them were given to us.

PORTENTS OF TROUBLE

While staying at Ganden, His Holiness came down with a serious intestinal fever for a few days, which caused everyone a great deal of concern and worry. However, the great being was fortified by his skill in cultivating spiritual protection, and thanks also to the medicine he was given, it did not worsen and he recovered fully.

After the functions at Ganden were concluded, on the way home His Holiness stopped at Tsal Gungthang, where he stayed on the top floor of the temple. Tutor Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché and I stayed in the rooms on the western side of the upper floor, which had in the past been my late father’s living quarters. After attending a grand feast of ceremonial cookies that Gungthang Labrang had offered, His Holiness settled in the garden cottage and said to the officials of Kunsangtsé, “Please bring me some texts to read.” Having not the slightest notion what books Gungthang Labrang held, they asked me. In the end we brought him the handwritten five-volume set of the teachings of Drogön Shang Yudrakpa262 that was in a collection of ancient volumes kept in a cabinet in the viewing room on top of the temple.

When I went to get the texts, my younger brother Tsipön Tsewang Döndrup came along. Having a bit of fun with him, I said, “You’re not capable of reading everything written in Tibetan.”

“What Tibetan is there that I cannot read?!” he demanded.

I showed him a handwritten analysis of the Perfection of Wisdom that contained an abundance of abbreviations wherein four or five syllables were condensed into one. He was unable to read it and shook his head in consternation.

REFLECTIONS ON IMPERMANENCE

As His Holiness relished examining the collected teachings of Lama Shang, Zhang Jingwu, the Chinese representative in Lhasa, informed him via the cabinet of the great number of casualties in Nyemo left by a confrontation between the Chushi Gangdruk militia and Chinese forces. He said that the Dalai Lama and the regional government must ensure that such attacks would cease, for if they did not, the Chinese would suppress them violently. His Holiness could not bear the news and was deeply troubled by it. The following day, he returned to the Norbulingka deep in thought.

That winter, as requested by Rabjampa Losang Wangden and others from Sera’s Ngakpa College, I visited Ngakpa College and gave a gathering of at least two thousand — largely monks from Sera — initiations into Akṣobhyavajra in the Ārya tradition of Guhyasamāja, thirteen-deity Vajrabhairava, five-deity Cakrasaṃvara, and Sarvavid along with their preparatory practices. I also offered permissions for the collected mantras of Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and Vajrabhairava. My visit to Sera coincided with offerings that the incarnation of Dromo Geshé Rinpoché was making to mark his geshé examinations. At his invitation, I stayed at his labrang for two days. I also went to the residence of the reincarnation of my supreme refuge Phabongkha Vajradhara and had a pleasant visit with him. While there I offered prayers for the long life of his tutor Gyalrong Khentrul Rinpoché, who was unwell.

Many times over the years up to that point, at the three seats, at Gyütö and Gyümé tantric colleges, and at Meru and Shidé monasteries in Lhasa, I had taught and propagated sutra and tantra teachings, transmissions, and initiations — chief among them the stages on the path to enlightenment — to gatherings of one or two thousand and at times up to four or five thousand, chiefly monks from the area or visiting from all over. Among the disciples there were anywhere between twenty and thirty, sometimes even up to sixty or seventy, incarnate lamas of various ranks as well as many geshés headed by the incumbent and retired abbots of the three seats, and many acclaimed scholars in the audiences assembled. But inside I knew I was a charlatan, hardened to the Dharma, a hypocrite whose deeds did not correspond with his words. As Paṇchen Losang Chökyi Gyaltsen said:

Teaching Dharma they are skilled in changing the minds of others,

but the dry leather of their own minds remains hard.

Teachers who expound like performers acting out a character

may find they possess no genuine Dharma.

Even so, just as long ago a wicked man who had killed his own mother entered the Buddha’s teaching, studied the scriptures, and led disciples to attain liberation by teaching Dharma disguised as a monk in a faraway land,263 in the hope that one among my many students would take up the great responsibility of upholding and preserving the teachings of the Buddha, I also did my utmost to pass on, as best I could, what few drops of the nectar of teachings, which easily show the path to freedom and omniscience, that my spiritual fathers, kind gurus who embodied all the buddhas, had deposited in my ears and heart. But like a herd of drunken elephants rampaging through a garden of lotuses, the barbaric Red Chinese, messengers of the devil, destroyed every last sign of goodness in the religion and people of the land of Tibet, such that it was impossible even to catch sight of someone dressed as a monk throughout the three provinces. Many great and promising lamas, incarnate masters, and geshés were crushed beneath the anvil of Chinese oppression. A few among that small number who followed His Holiness, our great refuge and protector, into exile in India also passed away, while others could not live up to the expectations of the monastic vows. As Ācārya Vasubandhu wrote:

When latent afflictions have not been eliminated,

and one dwells close to their object

with wrong and misdirected attention,

the causes for those afflictions to manifest are complete.

When I reflect on these dashed hopes, I feel that my work, like a sand castle built by a child, has left no trace, and I am saddened. But what could I do?

HIS HOLINESS’S FINAL EXAMINATIONS

As was tradition, on the first day of the first month of my fifty-ninth year, the year of the earth-pig (1959), I participated in the atonement ritual and offering in the bedchamber of His Holiness’s quarters at the Potala in front of the image of Palden Lhamo that had spoken. Early that morning, I also attended special New Year’s Day torma offering to this deity on the roof of the Potala, and I attended various other ceremonies throughout the day. A light snowfall on the morning of New Year’s Day seemed to be an inauspicious indication of the general disruption of religious and secular life during that time of upheaval.

That year, to mark his successful completion of intensive study of the five great treatises, His Holiness ceremonially traveled to the complex on the upper floors of the Lhasa Tsuklakhang in preparation for the final geshé examination by scholars of the highest standing, which would take place during the Great Prayer Festival.

The thirteenth day of the Great Prayer Festival, the day of His Holiness’s actual geshé examination for the rank of lharam, included an early morning assembly with communal tea and oral examination in the teaching courtyard, a midday assembly with tea, an oral examination during a dry afternoon assembly, and an evening session with more debating. During each of the assemblies with tea, His Holiness would give explanations on the great treatises and offer verses of homage. Nearly thirty thousand monks, arrayed like garlands of amber or like a vast field of marigolds, attended the examinations between the morning and afternoon assemblies and the lengthy evening session.

Among the masses of great learned propounders of philosophy were geshés of the three seats as full of confidence as Dignāga and Dharmakīrti, and they mounted challenges regarding the thornier points of the treatises on logic and epistemology in the teaching courtyard during the morning. In the afternoon session, they debated Madhyamaka and the Perfection of Wisdom, and in the evening Vinaya and Abhidharma. The lotus of faith and respect bloomed in the discerning who witnessed him responding freely and without hesitation to the logical and scriptural challenges offered. I felt deeply fortunate to witness the wondrous spectacle, watching him wither the creeping vine of audacity in those who were so arrogantly proud of their learning and trample the hooded snake of pride underfoot. During the afternoon oral examination, the great Dharmarāja from Nechung, again through his medium in trance, examined His Holiness, taking up the topic of the four noble truths, and offered him congratulations.

On the fourteenth, in the great courtyard of the Tsuklakhang, the government offered His Holiness an elaborate grand feast of ceremonial cookies and a great quantity of offerings of such value and wealth as would diminish even Vaiśravaṇa’s haughtiness to celebrate the successful completion of the ceremonies for his geshé examination. At the same time, the Sharpa Chöjé Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché, myself, and the assistant tutors were also each given fine gifts as a reward for successfully managing His Holiness’s education.

During the annual invocation of the Nechung oracle at Lhasa’s old Meru Monastery on the twelfth day of the first month, as well as during the additional invocation in the Ganden Yangtsé chamber on the upper level of the Tsuklakhang on the seventeenth, the Dharma protector spoke, saying, “I, the formless spirit, will attempt to build a bridge over the fordless Chinese river.” At the time we took the statement to mean that he would search for some means of restoring and normalizing the deteriorating relations between China and Tibet. But looking back on it later, I was convinced that it was his solemn, unbreakable pledge that allowed His Holiness and his hundredfold entourage to simply walk out of the city without the slightest opposition, despite every strategic passage from Lhasa being surrounded by permanent units of Chinese troops.

As the Prayer Festival neared its conclusion, His Holiness presided over a midday assembly, as was tradition. Similar to the system of oral examinations that some schools use nowadays, after I had recited a number of different verses that appear among the five great treatises, His Holiness explained the meaning of the verses, using dialectical supports to establish his reasons. After the noontime assembly, he gave a brief discourse and engaged in debate before many scholars in the courtyard of the Tsuklakhang.

One day a message came from the Chinese officials that there would be a theatrical performance at the Siling Puwu PLA military encampment that evening and that Tutor Ling Rinpoché, myself, and members of the cabinet must attend. Prior to that, we had received reports from Kham and Amdo that many prominent lamas and leaders had been arrested, sentenced, and hauled away when they had accepted invitations to such meetings and events. With thoughts circling around in my mind, I attended in a state of terror, thinking that the Chinese would deceptively use that night to lure us into a trap. Such anxieties reveal the sense of self-preservation that lingers after empty talk of the profound view and training the mind is finished. In fact, the Chinese were just using it as a test run for their later intrigue to invite His Holiness. And so we were received with cordial hospitality in the form of food, drink, and so on and were allowed to leave amid a show of smiles and pleasantries.

As members of the Sangha, monks are worthy of respect and service and are the supreme objects to make offerings to and by which to accumulate merit. Motivated to gather merit from the practice of giving, I had every year for several years been making offerings of tea, rice meal, money, and capital funds at the Prayer Festival. I made offerings at this Prayer Festival as well, but this was the last time I gathered merit at such an event in Tibet.

I summoned Panglung Chöjē, a medium of Shukden, the chief protector, who has long looked over me, to my house and invoked the protector in trance to inquire about what future course of action should be taken. In his prophecy he said that the wicked designs of the Red Chinese, enemies of the Buddha’s teaching, would soon become clear, and that it was thus imperative that His Holiness and all of us secretly depart for India. He said that it was absolutely unacceptable for me in particular to remain in Tibet, and that I must find some means of leaving. He also said that it was imperative that I urge His Holiness to go, that we must go, and that there would definitely be an occasion on which we could leave. I nevertheless remained indecisive. When His Holiness had not yet made up his mind whether to stay or leave, how could I think of leaving myself?

At the conclusion of the Prayer Festival and after the procession of Maitreya,264 I accompanied His Holiness when he traveled from Lhasa to the Kalsang Palace at Norbulingka in a grand procession with an ocean-like entourage.