Subdistricf

level

(Modjokuto)

The Islamic law (sarak) is, in Gibb’s phrase,1 the very conscience of Islamic culture; it is through the law that the commands of God, as given in the Koran, are translated into concrete prescriptions for secular behavior. Thus, in a sense, there is no genuinely secular behavior for a true Moslem just as (as we shall see) there is properly speaking no “state” as opposed to “church.” All aspects of life fall within the jurisdiction of the law; and, as the law is sacred, all aspects of life are in theory sacred. This is the real meaning of theocracy in Islam: the unreserved acceptance by the ummat of the prescriptions of the law as binding for daily life “in all its parts and activities.”2

Since the death of Muhammad and his immediate successors, such theocracy has everywhere proved possible only of approximation. Everywhere the Moslem law has had to compromise with local custom. Everywhere the effort of the pious scholars and judges has been to extend the sacred law into the whole of a given community’s secular life, to establish Dar Ul Islam, “the abode of Islam.” And everywhere this effort has been resisted by the less pious. Thus the administration of the law is a crucial practical concern of the leadership in any Moslem country. This is no less true in Indonesia, where the compromise the sacred law has had to make with engrained tradition has, perhaps, been greater than in many other Islamic countries. So we find in Modjokuto a third social form—in addition to the party system and the network of Islamic schools—in which the santri religious orientation is embedded; the religious bureaucracy.

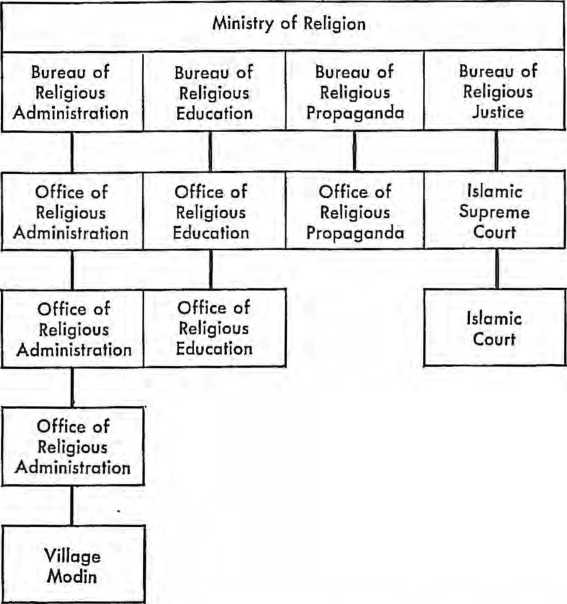

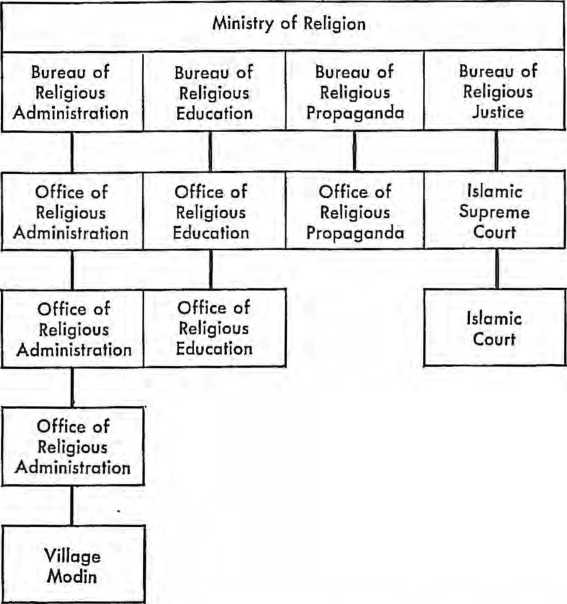

by “the religious bureaucracy” I mean the Ministry of Religion3 and its subordinate bureaus and offices, which administer all government regulations concerning religion. Although there are Protestant, Roman Catholic, and “Other Religions” sections, the Ministry of Religion is for all intents and purposes a santri affair from top to bottom. A much simplified organization chart of the Ministry follows.4

Subdistricf

level

(Modjokuto)

National

capital

level

Provincial

level

Regency

level

Village

level

Concerning the national, provincial, and regency levels little need be said here. The Minister of Religion has been a member of either Masjumi or

Nahdatul Ulama in all the cabinets,5 and almost all the offices in the bureaucracy are occupied by members of these two parties, plus a few scattered people from minor santri parties such as Partai Sarekat Islam Indonesia (PSII). One of the most important informal functions of the ministry is, then, to provide jobs for deserving Moslems, a function extremely valuable in terms of patronage for santri party leaders attempting to build up local machines.

The Bureau of Religious Administration is the largest and most important of the four bureaus and the only one whose branches extend to the Modjo-kuto level. Besides the technical management of the ministry as a whole— budgeting, the arrangement of office complements, etc., the Bureau of Religious Administration is concerned with the administration of the marriage and divorce laws and laws relative to the setting up and maintenance of religious foundations (wakap); listing and reporting on the condition of private mosques and inspecting their finances:6 the organization of the pilgrimage, which is now managed by the government in every detail; and the collection of various sorts of statistics, such as the number of religious schools, teachers, and students, the number of registered circumcisers, and the like. The Protestant, Roman Catholic, and “Other Religions” offices are under this bureau, but, except in heavily Christian areas and in “Hindu-Buddhist” Bali, such offices are confined to the national level. (Hesitancy on the part of Christians about allowing any official interference in their affairs by an almost wholly Moslem government reduces the ministry’s functions in relation to them largely to counting the number of churches, registering Christian marriages for the record, and publishing a booklet on Christianity every now and again to show that the ministry is “for all religions, not just Islam.”)

The Bureau of Religious Education is concerned with providing religious instruction in the public schools; awarding subsidies to private religious schools; running such government-owned religious schools as the Islamic University in Djokjakarta (Perguruan Tinggi Agama Islam Negeri) and several government-owned schuols for religious judges and for religious teachers; providing Moslem chaplains for prisons, the army, police barracks, and the like; printing and distributing schoolbooks on religion, including translations of foreign books. The Bureau of Religious Propaganda is concerned with distributing pamphlets, booklets, posters, and the like concerning Islam and in providing translated sermons (chotbah) for use in local mosques if the directors of the mosque so desire. The Bureau of Religious Justice regulates the Moslem courts, the function of which in turn is to give advice to those who request it on difficult points in the Moslem law—most often centering around inheritance7—and to grant divorces to women who complain of desertion or maltreatment under the clause permitting divorce for such reasons included in every marriage contract.

in a subdistrict capital such as Modjokuto, where there is only an Office of Religious Administration (Kantor Urusan Agama, commonly referred to as KUA or the Kenaiban, from naib, the chief official in the office), whatever functions of the other three bureaus need to be performed at that level are either channeled through it or, more commonly, handled directly by the regency or provincial office. Thus the religious teachers in the government schools are supervised by the Regency Office of Religious Education in Bragang, the regency capital, and the one religious scholar in the area— a Masjumi leader—who prepares Friday sermons for government distribution works directly out of the Office of Religious Propaganda in Surabaja, the provincial capital. As for legal advice, the local naib will give it if he is able, which is not likely if the case is very complex, but if not he will refer the petitioners to the Islamic Court in Bragang.

The head of the local KUA is the naib. Under the new set-up there should be a “Head of the Religious Office” (Kepala Kantor Urusan Agama) over the naib, so that Christians cannot argue that the office is entirely Moslem; but in Modjokuto (and, I imagine, elsewhere on the subdistrict level) this has not yet been instituted and the naib heads the office as traditionally. His duties mainly concern the general direction of the office and the regulation of marriage and divorce. He is assisted by a staff consisting of the chotib, who has as his special duty the giving of information talles to Moslems about the requirements of the Islamic Law; the imam, who leads the worship in the Modjokuto mosque and is generally concerned with problems focusing around religious ritual; the mukadin, who assists the imam and who calls the ummat to prayer from the mosque tower; the merbot, who cleans the mosque, office, etc.; and the ketib, who is the office clerk. Actually, the table of organization, although all the jobs in it are filled, is more theoretical than actual, and in Modjokuto all the officials (except the merbot, who is a janitor pure and simple) do all the work of the office without any apparent division of labor among them, save for the general executive functions of the naib.

ideally, the KUA should, from a santri point of view, be concerned with administration of the whole of tire Moslem law, but in fact it is largely restricted to that surrounding marriage, divorce, and remarriage. Under Moslem law a man who wishes to divorce his wife must pronounce the so-called talak phrase: “Kowé kok-talak" (“You I divorce”). If he pronounces the talak only once, he may change his mind at any time within three menstruation periods and take his wife back, a process known as rudjuk. He then has two talalcs left. He may, say ten years later, dismiss his wife again, and then remarry her within three menstruation periods. If after either of these first two talaks he does not remarry her within the prescribed three-month period, the pair is irrevocably divorced and cannot remarry unless the woman has in the meantime married and been divorced from another man. Similarly, after a third talak (i.e., after two rudjuks) the pair cannot rudjuk and so cannot remarry unless the woman has married and been divorced from another man in the interval. It is also possible for a man who is particularly angry at his wife to issue two or even three talaks at one time, making rudjuk impossible; but the naib usually attempts to discourage this latter practice as rash and unreasonable. The administration of this and of the marriage law takes up probably 80 per cent of the time of the officials of the KUA in Modjokuto.

the other 20 per cent of the officials’ time is employed in gathering various statistics about the ummat, running the Modjokuto mosque, giving courses for village modins (a class being held each Thursday morning in the Kenaiban for these village religious officials, the instruction dealing largely with their duties and with various elementary points of Moslem law), regulating religious foundations, and, to some extent, organizing the pilgrimage.

A religious foundation is called a wakap. It may consist of nearly anything of value—house land, buildings, rice fields. The wakap is usually made over by the donor to a local Icijaji or, sometimes, to the ?iaib, who is then its executor (nadjir) but not its owner, for it is considered to be the property of God. It is not taxed, but the government requires that all products of the wakap—for example, coconuts from a wakap garden—be recorded by the naib's office as well as all expenditures for repair of buildings and the like, to prevent misuse of wakaps by dishonest nadjirs. The nadjir appoints his own successor before he dies. Several mosques, langgars, madrasahs, pondoks, and Moslem schools in the area are wakaps, some with a little wakap rice land to help pay expenses. Large, extensive wakaps covering many acres or controlling great amounts of wealth, do not exist around

Modjokuto; and, although the naib's supervision of it is more theoretical than actual, there is no apparent abuse of the system such as occurs in some other Islamic countries.

For the most part, the organization of the pilgrimage is handled directly from the regency office, the Kenaiban merely keeping the statistics on the number of hadjis* giving out information on the process, and the like. The pilgrimage is carefully regulated from beginning to end by the Ministry of Religion. The would-be hadji merely pays a lump sum (Rp 7,300 in 1954) to the ministry, which takes care of everything including ship passage and room and board in Mecca, and even doles spending money out to him, the whole three-month trip being planned in every detail by the government. That this kind of regulation is, to an extent, necessary is shown by the description an old hadji informant gave me of the situation as it was in the Dutch period.

He said that there were many ticket brokers, both Arabs and Javanese, who often swindled people. They sold ship tickets to the peasants about to go on the pilgrimage, and made a tremendous profit from it. If a ship ticket cost Rp 550, they would tell the peasant it cost Rp 575; and, as the peasant knew no better, he was entirely at the mercy of such dishonest brokers. Worse yet, once the peasant was in the hands of a broker like this, the latter kept milking him of more money. Thus, when the prospective hadji arrived in Surabaja, he might find that he had to pay five rupiahs a night to sleep there until his ship left, often not till a month or so later, the broker having deceived him about the departure date. (The elder brother of the storekeeper on the corner had to wait 26 days in Surabaja for his ship, the storekeeper told me, and just about exhausted his resources.) Then he would have to pay five rupiahs more for various services upon embarking, one rupiah for a bus to the dock, and so on. Each time the pilgrim’s baggage moved around or got stored, the broker gobbled up a few more of his long-saved rupiahs. Another swindle the brokers practiced was selling time. A would-be hadji, for example, might give the broker Rp 500 for the trip, and the broker would buy a ticket for a ship due to leave in two weeks. However, he would hold the ticket and not tell the anxious pilgrim that he had already obtained it, telling him instead that he was still looking for a ticket. What he was actually looking for was a richer man who would pay more for the ticket in order to get a ship just about to leave. The broker would then sell the ticket for Rp 550 to the rich man and buy another for a ship sailing in a month or two. The routine would then be repeated, while the poor pilgrim out in the village waited impatiently, constantly assured by the broker that it would not be much longer. After six months or so, the pilgrim would finally get his ticket, but only after having provided free capital for the broker for half a year. After he got on the ship, his troubles were still not over, for there he would run into even more brokers trying to sell him a place to sleep in Mecca, tours to Medina, and so forth.

As there has been a severe shortage of foreign exchange since independence, the number of people allowed to make the pilgrimage has been drasti-

* A census made in 1952, which was probably inexact, revealed 194 persons who had gone on the pilgrimage at one time or another living in the subdistrict. Of these, 27 were women.

cally limited during the past few years. (The quota for the whole regency of which Modjokuto is a part was only 37 in 1954.) A prospective hadji must first convince his village chief that his family will not suffer, economically or otherwise, if he goes on the pilgrimage. He then must take a physical examination and a written or oral test on religion and on Indonesian affairs. (E.g. : “Who can go on the pilgrimage?” “Moslems who are not crazy, slaves, or children.” “What happened on August 17, 1945?” “Indonesia’s independence was declared.”) The individuals then actually allowed to go on the pilgrimage are chosen by lot from among those eligible, except that people turned back in previous years are given priority.

Actually, the limitation on the number of hadjis is not felt as much of a hardship by the ummat because the pilgrimage is not nearly so popular as it once was. In the towns, interest in the journey to the Holy Land has practically died out altogether. There has not been a single pilgrim from the town of Modjokuto since 1930; and each year since the war all applicants for the trip in the district have been from the countryside. When I asked people why this loss of interest had occurred, they usually said that people no longer feel that they have to go to Mecca to find out about Islam, since there are good schools for it in Indonesia; that people in towns prefer to plow the money they save back into their businesses rather than “throw it away” on a trip to the Middle East; and that, anyway, going on the pilgrimage is nothing so special any more.

(The informant made the pilgrimage in the late twenties.) When he was a child there were only about fifteen or so hadjis around, and they were very honored, each one usually having one or two hundred people as followers. However, as time wore on, more and more people made the pilgrimage and this reduced the homage paid to hadjis because they were no longer anything particularly out of the ordinary. Formerly, the pilgrims were the only villagers who had been out and seen the world; but nowadays you can get to Surabaja in two hours by car, so this doesn’t count for much any more.

in addition to their administrative duties, the officials of the Kenaiban are charged with the task of enlightening the rural masses as to the basic requirements of Islam and as to what the Ministry of Religion is attempting to do, a duty they fulfill by traveling around to all the villages in the subdistrict to give talks on subjects related to the work of the office.

Hadji Arifin (the chotib, speaking in a village near town) talked about marriage and divorce. He said that the KUA is much interested these days in “improving marriage.” He said marriage is an important problem to Indonesia, which is trying to build itself up to be a first-rate country. Divorce, he said, is tough on the women and on the children especially, for they are the ones who really suffer, grow up uncared for, uneducated, all this at a time when Indonesia is trying to build up the country. He quoted some

Arabic from the Koran and translated it to show that God is not in favor of easy divorce; and he said that in line with this KUA is endeavoring to bring about marriages which are “true marriages” and which last. He said they have made some progress, but things are still bad. Last year, before starting their propaganda campaign, they had 800 divorces per 1,000 marriages and now it is down to about 500 in 1,000. (These figures are exaggerated, but only slightly: the Javanese divorce rate is very high.) Obviously, he said, we need more diplomacy in marriage, and also people who are about to marry must truly want to. . . . He seemed to place all the blame for marriage failures (perhaps because he was speaking to an allmale audience) on the men not knowing their duties and so forth. . . . He gave some examples of masculine neglect culled from his experiences in the Kenaiban as the kinds of things to be avoided. The first was about a man who went to the movies when his wife was having a baby. He said this is the way love gets lost. The second had to do with men who don’t help their wives with the wife’s work when it gets too heavy. If the wife’s work is too heavy, this can cause divorce; and a man should not have rigid ideas about what is properly his work and what is his wife’s, but should help the wife if she is overloaded. The third example was of a village man who sold his harvest and then didn’t take the money home but bought himself a sarong with it, which made the wife angry because he had not discussed it with her first. . . . Then he went on to the problem of registering marriages with the KUA. He gave the number of the national law involved here and said that as Indonesia is trying to become a law-regulated state people must obey the laws. Only two religions have as yet been accepted by the Ministry of Religion: Islam and Christianity; the others have not yet been acknowledged. If a marriage is not recorded in the KUA, the couple are living in sin; also, marriages which are just a meeting of minds (“I am willing”—“I also am willing”) are sinful. The lack of registration leads to other things, such as a man having many wives in various places because there is no way to check on him. Then who is the victim? Our women.

But the main mediation of the interests of the Ministry of Religion to the villages is carried on by the modin. The modin is elected for life by his fellow villagers. (In order to stand for nomination he must take a simple examination in Islamic law and must be literate.) He is actually subject to two ministries at the same time: the Ministry of the Interior, as a village civil servant, and the Ministry of Religion, as the village religious official. (There may be more than one modin to a village, or one chief modin and several assistants.) His religious duties are twelve: (1) to prepare corpses for burial and to give advice to the survivors on the proper conduct of the funeral; (2) to see that the graveyards are kept up (the actual cleaning being done by a handyman who gets small donations from families who have relatives buried in the cemetery); (3) to conduct people who wish to be married to the Kenaiban after checking to make sure that everything is as it should be—that the girl has the right wait (guardian), that the man is unmarried, etc.; (4) to perform similar duties in divorce and (5) remarriage cases; (6) to give advice to people on inheritance according to Islamic law (although usually he tries to get them to settle their differences by customary law so as to avoid open breaches and if unsuccessful refers them to the naib)\ (7) to perform the slaughtering of oxen, goats, or sheep, which he must report to the subdistrict officer after having inspected the meat* (since people disobey with impunity the rules requiring goats and sheep to be slaughtered by a modin, and almost all oxen or water buffaloes are slaughtered in the town at the abattoirs, this is not of too much importance to the average modin); (8) to pray at slametans if requested to do so; (9) to give advice and consolation to people who have recently lost a relative by death; (10) to see that the religious tax is correctly gathered and not embezzled (not making the collection himself but checking on the organizations which do—at least theoretically); (11) to answer any attacks upon Islam and defend the faith against the criticism of infidels; (12) to provide an example for the villagers by himself carrying out the religious and social duties of Islam correctly and completely. The modins, who, naturally enough, tend today to be village political party leaders as well as traditional religious leaders, provide the main contact with Islamic law for almost all the abangans and many of the less educated santris, and as such they wield considerable power. They are paid, as are all other village officials, by a grant of land from the village rice fields, which they then work.

two rather more general problems demand discussion in connection with the religious bureaucracy: first, the relation of the bureaucracy to the two-winged party structure which I have already described as being pervasive in santri life; and, second, the place of the bureaucracy in respect to the Islamic formulation of that fundamental concern of all religious political theory— the proper relation between “Church” and “State.”

As for the party problem, I have already related how the prewar ideological struggle between the modernists and conservatives reached its point of maximum intensity in a fight over succession to the post of naib within the family which had dominated the Kenaiban since its founding in Modjo-lcuto. With the abolishment of the semi-hereditary system encouraged by the colonial regime and the substitution of a modern rational-legal bureaucracy and the ever-increasing tendency for posts to be filled in terms of party patronage, the family which had so long controlled the offices was no longer able to do so. Although the naib who had earned his succession by bitter intra-family maneuvering was not displaced from the bureaucracy, in 1950 he was promoted and moved to another town. The establishment of higher posts in a bureaucracy which had once been almost entirely local

* The slaughtering of animals is a duty of the modin because Islamic law prescribes rituals which must be performed when an animal is killed in order to make the meat lawfully edible.

means that the possibilities for mobility are made comparable to those in the civil service, with the result that the old stability of tenure, in which a man who was appointed naib remained naib until his death, has been disturbed and replaced with a system in which there is a constant turnover of personnel and a continual jockeying for position between the two major santri parties.

In any case, after the old naib, now a Masjumi member, had been transferred, Nahdatul Ulama was able, in part because its national head was Minister of Religion at the time, to take over all the posts but one in the Modjokuto KUA. (The naib is the chairman of Modjokuto NU; the imam is the party secretary.) This event very much disturbed the modernists.

H. Husein (a Masjumi leader) said that now the NU people have just about taken over the Ministry of Religion and regard it as their province. He said that H. Muchtar (the chotib) is the only Muhammadijah-Masjumi man in the Modjokuto office now, and that he wouldn’t be there if it were not that he is so clever and knows so much about the situation around here, having lived here all his life, that they can’t do without him. If perchance H. Muchtar had been stupid, they would have kicked him out long ago and there wouldn’t be any Masjumi people left.

Thus the control of the local religious bureaucracy is an important issue in party politics and tends to have significance for the organization of the ummat generally, determining even the choice of mosques.

He (a young modernist and a member of the family which controlled the office of naib before the war) said that in the old days when his uncle was the naib here there were many more people who went to the mosque here on Friday—so many that they spilled over into the yard. In those days Ali (chairman of Masjumi), Iskak (chairman of Muhammadijah), and the naib himself gave the sermons. Now the new naib is not so good and is not so well liked; and so things are calmer, and nearly all of the sermons are given by NU people and are mostly about religion, with only “We must choose an Islamic State” tacked on at the end. Now many of the Muhammadijah people go to other mosques—for example, to Banjuurip (a village Masjumi stronghold about five miles from Modjokuto). . . . He said that most of the sermons are about the same nowadays since NU took over—fear God and behave yourself—and are not very interesting. They don’t suit the times.

Although the NU control of the Modjokuto Kenaiban gives that party an important advantage over Masjumi, Masjumi leaders seem to do better at the regency and provincial levels (although the penghulu, the head of the regency religious bureaucracy, is also an NU man now, being the son-in-law of a Modjokuto NU leader, and the modernist family which used to control that post no longer does so). One Masjumi leader is employed—“part-time” —in writing sermons for the Provincial Office of Religious Propaganda (headed by a Masjumi man) to distribute to local mosques. The head of Muhammadijah is employed—“part time”—as a chaplain to the army by the Regency Office of Religious Education. And the chairman of Masjumi is employed—“part-time”—as a school inspector for all the private religious schools and madrasahs in the Modjokuto area which receive subsidies from the Ministry of Religion, a job which not only allows him to go around to all the villages and combine official work with party work but also provides him with a motorcycle on which to do it.

It is not necessary to trace here the manifold ways in which the religious bureaucracy and the party structures intertwine, the manner in which party interests can be served by control of various ministry offices, or the ways in which the bureaucracy responds to the tensions and pressures of party politics. But one issue—that of subsidies for religious schools—reflects the interaction between the two structures rather vividly and leads as well directly into the “Church” and “State” problem.

The response of the various groups to the idea of government subsidies for private religious schools takes pretty much the forms one would expect. Pondok kijajis, for the most part, want to have little to do with the government as it is now constituted because they feel that the requirements their institutions must meet to be eligible for the subsidies limit their personal freedom to run their own affairs in their own way. Moreover, they are suspicious of a secular government in which non-santri prijajis, occupying the great majority of the civil service posts, play such an important role. What they would like, and what they agitate for, is an “Islamic State” dominated by kijajis which would give subsidies to pondoks on the same basis as the religious tax is now given them by the populace generally: as a divinely commanded obligation of the less religiously concerned toward the more religiously concerned and with no strings attached except that the religious education must be orthodox.

Madrasah directors are willing to accept subsidies and to reform their schools slightly to get them, but are both unwilling and unable to sacrifice religious training in order to raise the level of their general education programs high enough to meet the comparatively strict technical requirements for private school subsidy applicants set by the Ministry of Education. As a result, NU leaders, as representatives of this group, have backed a policy of “something for everyone, no matter how little,” in setting up within the Ministry of Religion a much smaller subsidy program for religious schools. As this party has had the dominant voice within the Ministry of Religion for most of its existence, this is the policy which has been followed. Every local religious teacher who is willing to add a course or two in arithmetic or writing Latin characters8 is given something, but usually very little. One NU school in Modjokuto had a Ministry of Religion subsidy of two rupiahs per child per year, and the total subsidy of another for the year came to 30 rupiahs. Thus the resources of the Ministry of Religion, small enough in the first place because most of the money for education is channeled through the Ministry of Education, are so diffused through the thousands of Indonesian religious schools, good, bad, and indifferent, as to be almost entirely ineffective. NU has, of course, lobbied for a larger total budget, but in a political context where the Ministry of Religion is only barely tolerated to start with by the majority of non-santri party leaders, this has not proved very successful.

Muhammadijah, and to a lesser extent PSII, while also interested in increasing the total budget, tend to favor a policy of fewer Ministry of Religion subsidies but larger ones. Caught between their inability to raise their standards to meet the requirements of the Ministry of Education (not always: some Muhammadijah schools do manage to qualify for the larger subsidies, and the Muhammadijah high school in Modjokuto was trying hard to raise its standards toward such an end) and a severe shortage of money which the present Ministry of Religion subsidy program does almost nothing to alleviate, they have argued for a concentration of the resources of the Ministry of Religion into a few large subsidies to be awarded to those religious schools most technically qualified to malee good use of them—i.e., their own schools.

The first point on the agenda (of a Muhammadijah school-committee meeting) was the problem of asking the government for a subsidy. This soon resolved itself into (1) asking for a subsidy for the high school from the Ministry of Religion and (2) asking for one from the Ministry of Education. The difference between the two is that the Ministry of Religion subsidy is small but quite easy to get, that ministry operating on the principle that “although only a very little, everyone is able to receive,” while the Education Ministry subsidy is larger and harder to get, since it demands “results” before one gets anything. . . . H. Ari-fin said he thought that the subsidies given by the Ministry of Religion ought to be made about the same size as those of the Ministry of Education . . . and that maybe all the Muhammadijah people in the residency should get together and ask the government to do this. Rachmad (head of the high school) was dubious about this. He said that it would be “striking blows” at fellow Moslems in NU who had madrasahs in the villages, because it would mean fewer and larger subsidies in the Ministry of Religion which would be harder to get, so that these little schools, with mostly religious teaching, would be out in the cold. . . . And so the question was, “Do we want to stir up bad feeling by ‘striking’ our NU friends or are we willing to do so for the sake of larger subsidies from the Ministry of Religion?” There were many aggressive jokes here about “blows” etc., and they finally decided to plan a regency meeting to push the idea of fewer but bigger Ministry of Religion subsidies. ... As for the Education Ministry application, they weren’t very optimistic but felt they might as well try: “More Muhammadijah students passed the government examination this year, and all they can do is reject us again.”

the problem lurking both behind this specific issue and behind the Ministry of Religion in general (which a number of non-santri parties wish to abolish) is the one Western political scholars formulate as the relation between Church and State. This formulation fits badly with Islamic political theory, however, because of the absence of a church and because of the theoretical ideal (if almost never the actuality) of absolute theocracy—of Dar Ul Islam, “the Abode of Islam,” which has been present in Islam since the days when Muhammad headed his own army and state and the first four caliphs to succeed him continued to be the supreme authority in both religious and secular affairs.9 Since the title-slogan Dar Ul I slain has been appropriated by santri fundamentalists in open military revolt against the established Republic in West Java, in South Celebes, and sporadically in Northern Sumatra, those santri parties loyal to the new national state and committed to parliamentary methods for pursuing their aims have adopted the title-slogan Negara Islam, “Islamic State,” to indicate the “theocratic” ideal for which they are agitating.

I put “theocratic” in quotation marks because a series of interviews with santri party leaders in Djakarta on the subject and my experience in Modjo-kuto have convinced me that not only is the idea of Negara Islam an extremely vague one to just about everyone who holds it (as, admittedly, is the opposed Negara Nasional, “National State,” of the secularist parties) but also insofar as it means anything to anyone, it means quite different things to different people. In general, more conservative people tend to conceive of a Negara Islam in terms of a theocracy more familiar to us— one in which kijajis will dominate. Even here the exact methods which can bring about such a domination in the absence of a church organization within Islam is not clear, although people suggest such notions as having a special parliament of kijajis to check on secular legislation passed by die regular parliament to make sure it is orthodox, placing kijajis in high government position or appointing the most learned one as Head of State, and introducing a great deal more religious teaching into the government schools—i.e., turning them into madrasahs. Presumably, it is for some such program as this that the santri rebels in West Java and elsewhere are fighting insofar as they are fighting for a program at all.

Modernists, on the other hand, although also committed to a Negara Islam tend to restrict it to a general proclamation of an Islamic State: that is, the institution of a law that no non-Moslem can be Head of State (an occurrence extremely unlikely in any case with a population 95 per cent of which is nominally Moslem), and a constitutional provision stating that laws should be in accord with “the spirit of the Koran and the Hadith,” leaving it up to the legislators themselves to make certain of this. (Negara Islam is perhaps the single most powerful slogan among the santri masses. Any party which came out flatly for a separation doctrine—such as the secularists support—would lose almost all its rural backing.) Obviously, such a doctrine is not much more “theocratic” in fact than the recent effort of a New England senator to get the U.S. Congress to pass a resolution declaring Christianity the official religion of the United States, although it has some of the same symbolic drawbacks in the eyes of religious minorities and those suspicious of organized religion that the proposed resolution did.

For people holding either of these positions, or just vaguely affirming the dire need for an “Islamic State,” the Ministry of Religion is an embarrassment because it dramatizes the fact that the State is not in fact officially “Islamic.” Both parties are caught between trying to widen the scope of the Ministry of Religion within the present secular government in order to increase their power within that government and realizing dimly that by doing this they are in part going along with a heterodox view of the relation between religion and politics. A number of religious scholars at a conference called by the ministry in 1954 tried to resolve this problem by declaring the Ministry of Religion a kind of “temporary Islamic State,” an agent of the government which, at least for the time being, was legitimately to be obeyed in terms of the Moslem law. (Actually, they extended this beneficence to the cabinet as a whole and to the president, but the point of the proclamation was to give the Ministry of Religion a legitimate status according to Moslem law.) A number of party leaders and religious teachers cried havoc at this, however, evidently fearing the world-wide tendency for the temporary to become permanent in things governmental, which, in this case, would cut the ground from under the struggle for an “Islamic State.”

I talked to Fachid (a young NU shopkeeper) about the Ministry of Religion conference in Sumatra which decided that the president and cabinet are a legitimate Moslem government and which some santri members of Parliament have been attacking. He said that it is only a temporary compromise until the general elections can be held. The problem is that the Kenaiban, under the Ministry of Religion, is marrying and divorcing people and performing other religious functions, and there had to be clarification as to how this was legitimate since some people had questioned it in terms of religious law. The result was that some kijajis looked into the law books and came up with this temporary legitimization which says the government’s efforts in the Ministry of Religion relative to religion are legitimate but must be reviewed again after the election. In the meanwhile, Moslems are to obey the ministry in things religious—for example, its determination of the day the Fast is to begin. . . . Fachid, evidently somewhat nonplussed at my interest in the subject and also somewhat depressed over the Church-State issue himself, said that, whereas Christians want a split between Church and State, Islam doesn’t permit this. Thus the problem is very difficult.

In any case, this note shows that in identifying separation as a “Christian doctrine” and non-separation as the Moslem one the santris are unable to support an open split between Islam and the secular government such as has occurred in Turkey. It also shows that some compromise is possible, with santris settling for less than an Islamic State if the government “does not transgress the religious law,” i.e., is willing to allow a certain degree of State-Church fusion to serve santri interests. In such a situation the Ministry of Religion may in fact turn out to be a permanent compromise which can resolve santri political theory with the facts of the situation, namely, that not all Indonesians by far are santris.

Actually, however, the type of political thinking done by people in all the parties tends to militate against this because each group—abangan, santri, and prijaji—sees the political struggle not so much as a process of mutual adjustment between their separate interests as parts of a larger society but as a naked struggle for power in which one group wins and the others lose.

Fachid went on to say that it is natural that every group has its own ideology and wants it to triumph. The Communists want Marxism, the Nationalist Party wants Nationalism, and the santris want Islam. No matter what, they are interested in winning and will give the elbow to the other groups in order to gain the power to put their own foundation under the State. When in power, they will of course take care of their own followers,

A man may have adopted children, but he always likes his own just a little better no matter how fair he may be. So each group tries to get its ideology and its own people into power. I agreed with this but said that maybe no one group will win such a decisive victory that the other groups can be ignored; and he said, “Well, it is so; the minority has rights. But an Islamic State will protect them.” (He mentioned that, although the Christians want a separation of Church and State,* when something like the forced Islamization of Christians in the Celebes occurs they want the State to do something about it.) If two men are running for election, the one who has lost can still spread his ideology, but the man who is in is the one who rules. It is like a store. The man next to me may run his business differently than I do and that is up to him, but in my store I run things my way. So if the santris are in control of the country, they will run it their way: i.e., there will be an Islamic State.

This “if we win it’s our country” view of politics is common to nearly all shades of party opinion, santri and non-santri; and the following transcript of a statement of it by a local Masjumi member may be compared to the NU quotation above.

He talked a little about the Islamic State, saying that some people are afraid it will mean they can’t gamble, drink, or hold slametans, and will be forced to pray. He said no, it won’t mean this, it will just mean that the laws will be Islamic. (Like just about everyone else I talked to on this subject, he could cite as an example only that thieves’ hands will be cut off.) He said that the government will be a legal Moslem government, fit to be obeyed in both reli-

* Though santris tend to discuss separation as a Christian doctrine, its main supporters in Indonesia in fact are the Nationalists, including the president of the country.

gious and secular matters. I asked if the Ministry of Religion was not this temporarily; and he said (wrongly) “No, not yet, it is just a ministry.” He said that later in the Islamic State the Minister of Religion will be the Prime Minister (his own idea, not Masjumi policy). I said: “Well, won’t the non-santris revolt if you try this?” he replied: “That’s the way elections are. The PNI [the Nationalist Party] wants the Pantjasila (President Sukarno’s Five Points, put forth as the ideological basis of a National State), the Communists want Communism, and the Moslems want an Islamic State; so whoever wins gets to put it in.”

H. A. R. Gibb, Mohammedanism (London, 1949), p. 10.

* 1 Ibid.

Almost every educated santri will tell you, “Israel is the only other country besides Indonesia which has a Minister of Religion with cabinet rank.”

Before the war, the religious bureaucracy was not nearly so elaborated as now. It lacked all of the middle-rank offices and bureaus which are now so important in its functioning and was of far less significance in the over-all governmental structure, being but a small division under the Education Department of the colonial government.

It was a conflict within the unitary Masjumi over whether a Muhammadijah or an NU man was going to get the seat in the Wilopo cabinet which finally drove NU— Muhammadijah having won the intra-party struggle—out of Masjumi in 1952.

Since mosques, especially in town, may be dedicated as wakaps with a proviso that the nadjir (official caretaker) be the head of the local religious office, this often includes the actual management of such mosques, although in theory all mosques are private.

One does not have to use Moslem inheritance law, however, and few people, even among the santri group, do. The Islamic courts have only advisory powers and may act only in cases voluntarily referred to them by petitioners who are free, so far as the civil state is concerned, to reject or ignore their decisions. Only concerning marriage and divorce are the civil and the Moslem laws fused (except for Christians and the Balinese, who are Hindus); in all other areas recourse to Moslem law is voluntary.

Pondok kijajis have largely refused to meet even this requirement. In Modjokuto no pondok was getting any subsidy while I was there, although the kijaji of one of the larger pondoks was thinking of asking for a few rupiahs for the student-run secular school included in his program.

Not only is there no church in Islam; there is properly speaking no state either. The basic political unit in Islam is the umma Muhammadiyya, Muhammad’s community, defined not territorially but legally, and composed of all those who follow the Moslem law: “Perhaps the greatest difficulty in the way of the new Arab countries is the necessity to overcome rapidly the traditional Islamic concept of, and attitude toward, the state as such. Islam never developed the idea of ‘the State as an independent political institution,’ which has been so characteristic of classical and Western thought. In Islam the State was not a [territorial] community or an institution, but the totality of those governed, umma, with the imam as their leader. As a result, the Oriental State had no conception of citizens in the modern sense. Government was not everybody’s business nor even that of a privileged class. Participation in executive power was, in the public mind, as haphazard and accidental as were, apart from taxation, the contacts of the individual and government in general.’’ (G. E. von Grune-baum, Islam: Essays in the Nature and Growth of a Cultural Tradition [Menasha, 1955], p. 73.)