ABOARD THE BELYI PRIZRAK, SEVERODVINSK, RUSSIA

PRESENT DAY

What did your father do with the stone after that?” asked Vladamir Krupnov.

Stephen Haroldson had just completed the story of his father’s experience during the British liberation of Tunis. “He kept it until the end of the war. Then he turned it over to the authorities when he got home. The amazing thing is, he never got any kind of reward or credit for discovering that stone and turning it over. No special recognition. Not even a medal.” Haroldson let out a sardonic laugh. “Instead, they told him to forget he’d ever seen it. That it was top secret and that there’d be repercussions if he ever told anyone about it . . . even his family.” Haroldson’s voice cracked on the last word. He cleared his throat and continued. “But what my father never told anyone, until just hours before he died, was that he’d actually broken off a small piece of that stone for himself. As a souvenir.”

“Your father was a smart man,” said Krupnov.

“He kept it hidden all those years in a small tobacco tin in the attic, in a box with all his army uniforms and his medals, and other souvenirs from the war. He never told anyone about it because he was afraid he’d get in trouble.” Haroldson sighed, apparently still sensitive about the recent loss of his father. “Anyway, after he passed, I found the piece of stone in the attic, right where he said it would be. And as soon as I saw it, I knew . . . my God, that must be worth a lot of money. I contacted Mr. Fulcher and he got back to me right away. And, well . . . here I am.”

“Yes, here you are,” said Krupnov with a crooked smile. He let those words sink in, as if weighing their significance. Then he raised his glass high above the table. “Gentlemen, a toast.”

The other two men followed suit a moment later.

“To Mr. Haroldson,” said Krupnov.

“Cheers,” said Fulcher, as they all clinked their glasses together.

“And to your father,” Krupnov added reverently.

“Thank you,” said Haroldson.

Krupnov drained his glass and carefully refilled it with more cognac. “Notice the rocking?” he said as he poured. “We’re in open water now.” He rose from his seat and looked out both windows. “Yes, we’re in the Dvina Bay, north of Severodvinsk. See there?” He pointed out the starboard window to the lighted shoreline in the distance. “Sevmesh is about four kilometers that way. And in this direction . . .” He pointed into the darkness out the port window. “ . . . is the White Sea, which extends north about two hundred kilometers to the Arctic Circle and the Kola Peninsula. The sea to the north is already frozen over by now.”

The other two men nodded and admired the view of the sparkling Severodvinsk shoreline.

Finally, Krupnov resumed his seat, set down his glass, and leaned forward on one elbow. “Now, Mr. Haroldson. If you’ll hand me the material, we can complete our transaction, and you and your wife can get on with your lives and all of your exciting travels.”

Haroldson swallowed hard. “What about the rest—” He cleared his throat. “The rest of the money?”

Krupnov laughed. “You’re not much of a businessman, are you, Mr. Haroldson?”

“Sorry?”

“You see, you’ve put yourself in a very vulnerable position here with no bargaining power at all. A better strategy would have been to demand that the full amount be placed into escrow before you boarded your flight from Helsinki.”

Haroldson looked stunned. “But I . . . I thought . . .” His skin was getting paler by the second. He looked back and forth between the two men at the table.

Krupnov laughed again and slapped the table loudly, causing Haroldson to flinch. “Relax, Mr. Haroldson. I’m a man of my word. I have every intention of wiring the remainder of the money into your account. I can do so in thirty seconds using my phone. But first, I need to see that material with my own eyes.”

Haroldson breathed an audible sigh of relief and slowly retrieved a small glass vial from his pocket, placing it on the table in front of Krupnov.

Krupnov picked up the vial with great care and held it up to the light. “Magnificent,” he whispered, staring in wonder at the tiny object inside. It was a shard of black stone, about the size of a small watch battery. And it was floating inside the vial, suspended inexplicably in midair. “It’s quite small,” said Krupnov, casting a sideways glance at Haroldson. “You’re sure this is the entire fragment that your father told you about?”

“Oh, yes. I’m sure.”

Krupnov appeared mesmerized as he twisted the vial back and forth between his thumb and finger, watching the object inside bouncing lazily off the sides. Finally, he put the vial down and stared at Haroldson curiously, as if sizing him up. The silence stretched into several seconds and became quite uncomfortable.

“So . . . what about the wire transfer?” asked Haroldson, breaking the silence. He glanced at Fulcher beside him and then back to Krupnov. “You . . . you said you were a man of your word.”

“So I am.” Krupnov retrieved his cell phone from his breast pocket and pressed a single button. He held it to his ear for a few seconds, then spoke into it in Russian, his voice calm and quiet: “Da. Zaydi.” He hung up the phone and smiled at Haroldson. “It’ll just be a minute.”

Thirty seconds later, there was a knock on the door and Misha, the husky sedan driver, entered the dining room. “Vyzivali?” he said to Krupnov.

“Gospodin Haroldson khotel by iskupat’sya,” said Krupnov.

The sedan driver nodded and immediately walked over to Haroldson and grasped him firmly by the arm, helping him to his feet.

“Wh—what’re you doing?” said Haroldson in a confused tone, rising to his feet. “Where are we going?”

“Go with Misha. He’ll take care of everything.”

“But . . . I don’t understand.” Haroldson’s voice was quickly giving way to panic. Misha prodded him toward the door, less politely now. “Wait!” exclaimed Haroldson, trying in vain to resist. “Please!”

Seconds later, Haroldson and Misha were out of the room.

Krupnov and Fulcher remained seated at the dining room table. They looked at each other in silence for a long while, as the sound of Haroldson’s struggling and pleading in the hallway gradually grew more distant. Half a minute later, he could still be heard shouting from the forward stairwell thirty feet away: “I don’t want the money! You can keep it. Please, just let me go! I have a wife!”

“A shame,” said Fulcher, shaking his head.

Krupnov nodded. He rose to his feet and walked over to the dining room door and gently closed it, shutting out the sound of Haroldson’s voice altogether. Then he returned to his seat. “So, do you think this is enough material?” he asked, picking up the glass vial.

“Enough to demonstrate the concept, yes.”

Krupnov frowned. “I’m not interested in ‘demonstrating the concept.’ I’m interested in making money.” He held up the glass vial containing the floating chip of stone. “So, is this enough to make our reactors work or not?”

Fulcher sighed. “No. We’ll need more seed material than that. Which is why it is so critical that we find Malachi. With the material from the Thurmond lab, we should have enough for at least one self-sustaining reactor. Maybe two. And once we find the rest of the Joshua Stone . . .”

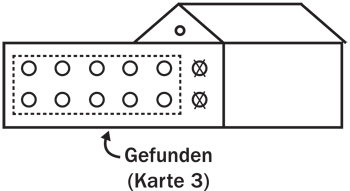

“Yes, about that,” said Krupnov. He reached into his pocket and retrieved a folded sheet of paper, which he quickly unfolded and spread out onto the table. The sheet was a photocopy of a tattered and stained notebook page with the following annotated drawing:

“Do you believe Malachi will be able to explain this?” Krupnov asked, somewhat doubtfully.

“Aside from Franz Holzberg himself, Malachi is our best bet.”

“You’d better be right,” Krupnov intoned sharply. “The posrednikov have invested a great deal of money in this project. You originally asked for five million euros, I got you five million. Then you asked for another ten million, and I got it for you. You asked for a reactor, we now have two reactors nearly completed. But not enough seed material to make either of them work. And, along the way, I have made certain assurances to the posrednikov, not to mention the Russian government. Do you understand what I mean?”

Fulcher nodded.

“I’m not sure you do. This is not England. The posrednikov expect results. If we fail . . .”

“Vlad,” said the older man calmly. “We won’t fail. Are you seriously doubting me now? After what I’ve just delivered to you?” He pointed to the glass vial on the table. “I was right about that chip, wasn’t I?”

Krupnov nodded.

“And I was right about Malachi, too. My timing was just a little off. All we need to do is find him. Quickly.”

“Da,” said Krupnov. “I am leaving for the United States tomorrow morning to supervise that operation myself.”

“Good. So you see? This is all going to work out just fine. It has to. It’s fate. And this is just the beginning. Soon, we will be in possession of the most powerful technology the world has ever known. Our reactors will revolutionize energy production and make oil and gas obsolete in a matter of years. Think of it: unlimited, clean, renewable energy with no radioactive waste. And the byproduct . . . a material with properties the world has never seen, with limitless applications for military, aerospace, transportation, and more.”

“Yes. It will instantly become the world’s most valuable commodity,” said Krupnov.

“And we alone will possess the critical seed material needed to make it.”

“I do like the sound of that,” said Krupnov with a smile. He raised his glass and took a sip.

“By the way,” said Fulcher after a pause. “What did you tell Misha?”

“Hmm? Oh, I just told him that Mr. Haroldson would like to take a swim tonight.”

“Ah.”

Seconds later, the flailing body of Stephen Haroldson suddenly flew past the dining room’s port window on its way into the frigid waters of the White Sea.

“Well, that eliminates one loose end,” said Krupnov.

“What about his wife?”

Krupnov took another sip of his cognac, savoring its smooth, intoxicating flavor. “She’s been dead since this morning.”