LANGLEY, VIRGINIA

Well, look who it is,” said Bill McCreary. He spoke these words to Mike Califano, who had just emerged from a black Apache helicopter at the rear of the CIA headquarters building. The two men quickly cleared the rotor zone and made their way to the headquarters building, where they stopped just short of the entrance.

Califano was still badly shaken up. His face and shirt collar were covered with blood, and his hands and clothes were filthy. He had a jagged, two-inch laceration and large scrapes on the right side of his forehead, which were thoroughly caked with blood and dirt. A green thermal blanket was draped around his arms and shoulders.

“What the hell?” said Califano. “You sent a bunch of SEALs to grab me in the woods? I thought they were going to kill me!”

“Sorry, Mike. We couldn’t take any chances.”

“Bullshit! You could’ve just called me on the radio if you wanted me to come in.”

McCreary held out his open palms. “Mike, you’ve been missing for three days.”

Califano’s face suddenly twisted into an expression of confusion. “What?”

“Yeah. It’s Monday night right now. You went down into the mine on Saturday morning. We weren’t sure if you were ever coming out of there, or what condition you’d be in if you did. I had those guys camped out in front of the entrance just to make sure you got back here safely. And they had to disarm you because . . . well, to be honest, we didn’t know what kind of physiological or psychological effects there might be. And by the way, those weren’t SEALs. Although some of them used to be.”

Califano still looked utterly confused. “But I . . . I was only down there for a couple of hours.” He extended his left arm. “Look at my watch.”

“I know,” said McCreary. His tone was calm and soothing, almost patronizing. “I’ll explain it all when you get to the workroom. But first we need to get you looked at. Medics should be here any—”

Califano cut him off. “I saw the lab.”

“You what?”

“I saw it. I went in. And then someone blew it up. Almost blew me up with it.”

Now it was McCreary’s turn to look confused. “You mean just now? Just when you were down there?”

“Yeah, man. Just now. I was down there, and I saw a bunch of stuff. There was some sort of swimming pool–type test rig, and Atomichron clocks, and instrument panels. Then all of a sudden I heard a beep and noticed there were explosives all over the fucking place. I ran like hell and barely got out of there before it blew.”

“Shit,” McCreary whispered. His eyebrows were scrunched together in an expression of confusion.

“Oh, and there were bodies. I counted at least five, including one in the cooling pool. They looked like they’d been shot recently. And there were two men leaving the mine just as I was going in. They were wearing gas masks and carrying guns.” Califano paused and took a deep breath. “Seriously, Doc, something really strange is going on down there.”

McCreary was just about to say something when his phone rang. He answered it quietly, listened for a few seconds, then turned back to Califano. “Med staff’s on their way.” Moments later, an ambulance pulled up to the circular driveway behind the building, and two paramedics jumped out.

Califano waved them off. “I’m fine,” he yelled to them.

“Michael, you have to go with them. They need to look at your head.”

“No offense, Doc, but I really don’t want any CIA people examining my head, okay?”

“Come on, you know what I mean.” McCreary pointed to his bloody right temple. “Your cut. It needs stitches.”

Califano lowered his voice to nearly a whisper. “Just tell me this. Am I gonna end up strapped to a bed like Holzberg? Drugged up and crazy?” He held McCreary’s gaze for a moment. “Well . . . am I?”

“No,” said McCreary reassuringly. “Of course not. They’re going to stitch you up, run some basic tests. Blood work, that sort of thing. And you’ll be back with us in a couple of hours. Look, we’ve got a lot of stuff to cover, so we don’t want you out of commission any longer than necessary. All right?”

Califano accepted this assurance and felt a little better. “Yeah, I guess.”

“Good. Now go get yourself fixed up. You look like shit.”

Califano managed a smile. Then he turned and made his way over to the ambulance.

It was nearly 11:00 P.M. when Califano finally returned to the workroom in building 1. Ana Thorne, who had just gotten back from Florida, was still in the process of updating Dr. McCreary and Admiral Armstrong about what she’d learned.

“I’m back,” Califano announced, entering the room with Steve Goodwin.

McCreary, Thorne, and Admiral Armstrong all rose to their feet to greet him.

Califano looked much better now than he had a few hours ago. He had showered and was now wearing a set of clean gray sweats, courtesy of the folks in the medical unit. He also had twelve stitches on the right side of his head, neatly dressed with a small, square bandage.

Ana was the first to speak. “Michael,” she said in a tone that was somewhere between Glad to see you and I can’t believe you’re still alive. She walked over to him and gave him a quick hug.

A hug from Ana Thorne? Califano marveled over this and quickly reciprocated, making the embrace last just a little longer than intended.

“Michael,” said Admiral Armstrong, putting his hand on Califano’s shoulder. “Looks like you got yourself pretty banged up there.”

“Yeah, just a bit.”

Armstrong’s grip tightened on Califano’s shoulder, and his tone suddenly sharpened. “And just what the hell were you thinking going down into that mine all alone? Completely unprepared. And without one iota of authority?”

“Yeah,” Califano mumbled. “Not my brightest idea, I’ll admit.”

Armstrong shook his head and let out an exasperated breath. “And yet, amazingly, not your stupidest either. Not by a long shot.”

Finally, McCreary spoke. “Michael, we’re all glad you’re back.” He motioned toward an empty chair. “Come have a seat and I’ll catch you up with where we are. Then I want to hear all about your adventure in the lab.”

They all took seats around a small conference table in the back of the room, except for McCreary, who remained standing. “Michael,” he said. “What I’m about to tell you is highly classified.”

“Isn’t all of this stuff?”

“Yes, but this gets into a whole different channel. I wasn’t authorized to tell you this before—”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” said Califano, stiffening in his chair. “You weren’t authorized?” An incredulous look spread over his face as he digested this comment. “Dude, I almost died down there. What, exactly, were you holding back?”

“Calm down, Michael,” said Admiral Armstrong. “He’s getting to it.”

“Look,” said McCreary sternly. “You weren’t even supposed to go down there, okay? You violated protocol, not me. So don’t start casting stones.”

“Okay, we get it,” said Armstrong, trying to keep the peace. “We’re all on the same team here.”

Califano exhaled and nodded. Shit. They were right. He’d crossed way over the line by going down into that mine. And he had no one to blame but himself for his injuries. “Sorry,” he mumbled. “Guess I’m still a little worked up.”

“It’s okay,” said McCreary. “You’ve been through a lot.” He paused for several seconds to collect his thoughts. “Okay, let me first explain about the time.”

For the next twenty minutes, Dr. McCreary explained in great detail about the “time dilation” technology at the heart of the Winter Solstice program. He explained that time dilation is a phenomenon whereby two different observers in two frames of reference experience time differently. He explained the classic example of the “twins paradox.” One identical twin stays on earth while the other travels through space at nearly the speed of light. When the traveling twin returns, he is chronologically much younger than his sibling, because of time dilation. That is, because time ticked by much more slowly for the traveler than it did for his brother back on earth. Finally, he explained that all of this was precisely as predicted by Einstein’s theory of relativity.

“And it’s been proven?” asked Califano.

“Absolutely,” said McCreary. “A very simple example is the clocks on our GPS satellites. They have to be adjusted by about thirty-five microseconds per day to account for the effects of time dilation. There are actually two different opposing effects at play there. Time runs a bit slower on board the satellites due to their high speed relative to the earth’s surface, and it runs a bit faster because of the difference in gravity between where the satellites are and where we are. Those two effects offset each other so that, overall, the clocks run a tiny bit slower on board the satellites than they do here on earth. And this has all been proven in countless experiments.”

“I knew about the speed thing,” said Califano. “But I didn’t know that gravity also causes time dilation.”

“According to Einstein, it does. What Einstein’s theory of general relativity says is that time and space are flexible. They can be stretched. And what stretches them are objects with mass. So if you take a massive planet like earth and you plop it onto the so-called space-time continuum, it will distort that continuum and cause other objects to be attracted to the depression in the continuum, just like water circling a drain. According to Einstein, that is the real explanation for gravity. It’s a phenomenon we observe because of the disruption of space-time. The farther you get from a massive object, the less distortion of time and space you are subjected to, and, therefore, the less gravity you feel. In simplistic terms, gravity slows time down by distorting it. And as you escape a gravitational field, time speeds up.”

“Can you feel it slowing down and speeding up?” asked Ana.

“No. Each person in each frame of reference experiences time perfectly normally. So a second always feels like a second and a minute always feels like a minute, no matter where you are. It’s only when you compare two things in two different frames of reference, like a clock on a GPS satellite versus a clock on the ground, that you notice the effects of time dilation.”

“And is that what happened to me?” Califano asked.

“Yes,” said McCreary, nodding. “And you were very lucky. Apparently, what you experienced were just the lingering aftereffects of a previous time-dilation event. If you’d been exposed to the full thing, we wouldn’t be seeing you for a long, long time.”

Califano furrowed his brow. “I don’t understand. You mean the event that happened way back in 1959?”

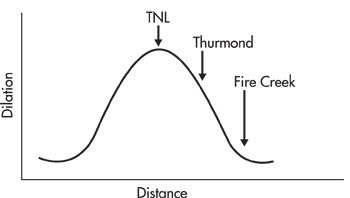

McCreary walked over to a nearby whiteboard and uncapped a dry-erase marker. “Here, let me show you what I think happened.” He quickly drew a bell curve on the whiteboard and labeled it as follows:

“On October 5, 1959, the researchers at Thurmond National Laboratory inadvertently triggered a massive time-dilation event,” said McCreary. “Time inside the lab slowed way down compared to time outside the lab. How much did it slow down? We can’t know for sure. For instance, if the actual event lasted only ten seconds in the lab, and we know that fifty-four years have elapsed since 1959, then the ratio would be something like 170 million to 1. If the event lasted an hour, then that ratio is more like 470,000 to 1. But whatever the ratio, time was crawling inside the lab, compared to outside, okay?”

Everyone at the table nodded. Indeed, this was the only logical explanation for Dr. Holzberg’s sudden appearance in Fire Creek after going missing in the lab fifty-four years earlier.

“Based on what we know about time disruption in Thurmond and Fire Creek, it appears that the effects of this time-dilation event varied inversely with the distance from the lab, as I’ve shown here.” He pointed to the bell curve on the whiteboard. “Thurmond was only a mile from the lab, and it experienced a dramatic disruption of time. So much so that the entire town was quarantined and then evacuated.”

“Yeah, the lady at the diner told me about that,” said Califano. “She also said the people who were relocated had all sorts of health issues, like loss of memory.”

McCreary nodded. “It appears this time-dilation phenomenon can have severe effects on the human body, including some manifestations of rapid aging.” He pointed again to his bell curve. “Now, Fire Creek here is about ten miles from the lab, and I understand the time disruption effects were much less severe there.”

“Three minutes a day,” said Califano. “That’s what Thelma Scott said. Every clock in town has been running three minutes slow since 1959.”

“Incredible,” Ana remarked, shaking her head. “How could that not have been reported in the news?”

Califano laughed. “If you saw Fire Creek, you’d know. It’s like the town that time forgot. Literally.”

Admiral Armstrong interjected. “Bill, why couldn’t they have rescued those people down in the lab in 1959?”

“They probably tried,” said McCreary. “But rescuing someone from a time-dilation event like this would be very difficult. Think about it. You send the elevator down, but the closer it gets to the lab, the slower time runs. So it could take years, in outside time, just to get an elevator down to the lab. And then it would take years to get it back up.”

There was silence around the table as everyone tried to wrap their minds around that concept.

“Look, we don’t know what rescue efforts were undertaken, if any,” said McCreary. “What we do know is that by November 1959, the decision was made to seal off the lab entirely, with everyone still trapped inside. My guess is they wanted to prevent anyone or anything from going in . . . or out. So they sealed the elevator shaft with concrete and created a fenced-in exclusion zone with a three-mile radius around the lab. They used the specter of radiation to keep people away, which was a pretty effective ploy. In truth, there probably never was any radiation associated with this event. In fact, what I saw up in Thurmond was a controlled gamma source in the elevator shaft that was probably placed there when the lab was decommissioned. This would have given the appearance that radiation was streaming from inside the lab. But I think we now have living proof that it isn’t.” He gestured toward Mike Califano.

Now Califano spoke up. “So how come Dr. Holzberg was trapped down there for, like, fifty years, but I only lost a few days?”

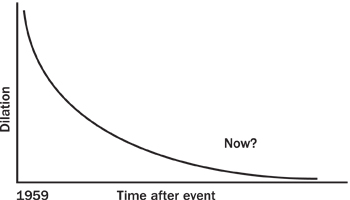

“Ah,” said McCreary. He quickly drew another curve on the whiteboard, and labeled it as follows:

“I’m guessing that the effects of time dilation decay something like this. Back in 1959, when this event first occurred, the time dilation was tremendous. For all we know, it might have taken them decades in our time just to get through the first few seconds of the event down there. But, as time moves on, the dilation becomes less and less. Until eventually, it returns to normal. So let’s see . . .” McCreary scrawled some numbers on the whiteboard. “You say you experienced an elapsed time of about two and a half hours, or a hundred and fifty minutes. Elapsed time outside the lab was two and a half days, or about three thousand six hundred minutes. That means you experienced a time-dilation ratio of about twenty-four to one. As I said, you’re damn lucky it wasn’t twenty-four thousand to one, or you’d still be down there.”

“What about our carjacker?” Ana asked. “He’s been spending fifty-dollar bills that weren’t even printed until 1970 and ’71. Assuming he came from the lab, how do you explain that?”

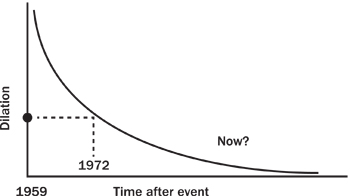

“Easy,” said McCreary. He quickly added some features to his second graph, so it looked like this:

“Let’s assume that guy entered the lab in 1972. In that case, he would have been exposed to time-dilation effects that were much less severe than what were experienced by Dr. Holzberg and the original crew. Perhaps the time-dilation ratio would have been cut in half by then, or even by two-thirds.”

There were baffled looks all around the table.

“Think about it this way,” said McCreary. “Put yourself in the shoes of Dr. Holzberg. It’s October 5, 1959, and a strange event has just occurred in the lab. Perhaps this event lasted for just a few seconds. But, unbeknownst to you, during that short span of time, ten years have gone by outside the lab. You go out and check the elevator shaft, and you discover, to your horror, that it’s been sealed with concrete. You’re trapped. A few more seconds tick by and suddenly someone arrives in the lab who says they’re from 1972. You wonder: How can it be 1972 already? It was 1959 just a minute ago. And then you wonder: How did this person even get down here with the elevator shaft sealed? And this guy says: ‘I know an escape route. A secret passage.’ ”

“Actually, it’s a cross-ventilation shaft to Foster Number Two,” said Califano.

“Fine, a ventilation shaft,” said McCreary. He pointed to his graph. “By now, it’s already 1995 or 2000 outside the lab. But to you, Dr. Holzberg, it still feels like 1959. And to your new acquaintance, the carjacker, it still feels like 1972.” McCreary suddenly turned to Califano. “Mike, how long did it take to get out of the lab through that shaft?”

Califano shrugged. “I dunno. Maybe five minutes.”

“Okay,” said McCreary. “So it takes five more minutes to get through this ventilation shaft and into the adjacent mine. Meanwhile, another ten or twelve years has gone by outside. You finally make it out, and it’s 2013. So you, Dr. Holzberg, have lost fifty-four years, and your rescuer, our carjacker, has lost forty-one years. But you both come out of the lab at nearly the same time.”

Everyone was quiet for a while until Califano spoke up. “A couple of problems with your time line, Doc.”

“Hmm?”

“Well, first of all, who shot Dr. Holzberg in the gut? Was it the carjacker, or was it someone else? Second, who killed all those people in the lab? Like I told you, I saw at least five bodies down there. And I know gunshot wounds when I see them. And third—and this is a big one—who set those explosives that blew up the lab? Remember, I saw two people heading out through Foster Number Two when I was coming in. They were wearing gas masks, and they were armed. My guess is, they’re the culprits. So where are they on your time line?”

“All good points,” said McCreary. “And here’s the answer. Those people you saw could have entered the lab at any time. They could have entered the lab in 1975, or 1980, or 1985, or really any time. But from the perspective of Dr. Holzberg and the others inside the lab, it still would have seemed like those men with guns came in just a short time after the original event. Everything would have happened in the blink of an eye. Perhaps Dr. Holzberg was caught in the crossfire and managed to escape, while the rest of the lab crew was killed. We just don’t know.”

“Jesus,” said Admiral Armstrong. “I don’t know about you people, but my head is starting to hurt. Just tell me this, Bill. What do we do now?”

“For starters,” McCreary said. “We need to find that Thurmond material ASAP. We can’t risk it falling into the wrong hands. As you can see, this is a very powerful technology. The effects of a larger-scale dilation event could be catastrophic. Not to mention that whoever controls this technology will have a tremendous technological edge over the United States. If the Russians are involved, as we suspect they are, then that’s even more of a concern.”

Ana rose to her feet. “To find this material, we need to find that carjacker. I’m convinced he’s the key to all of this.”

“And where are we going to find him?” Califano asked.

Ana arched her eyebrows and nodded toward the computer that Califano had been using three days earlier to run his data-mining program. “Isn’t that your job?”