PROLOGUE

No one would claim to understand every part of these stories, or to have a ready explanation for people, events, or processes that are confusing and strange. These are stories that defy any complete understanding. To tell and to listen to them is to experience the delight and enigma of incomprehension. Mysteries are repeated, not explained.

—HUGH BRODY, The Other Side of Eden

IN THE DARK, NEARLY SUNLESS DAYS OF AN ARCTIC NOVEMBER, two Catholic priests, exhausted, freezing, and nearly mad from starvation, were hauling their gear south, away from the continent’s northern edge. Father Jean-Baptiste Rouvière, slight and dark-eyed, and Father Guillaume LeRoux, strong chinned and defiant, were dressed unusually, given the increasingly severe weather. Under their parkas, their long black cassocks, buttoned down the front, seemed insufficient protection against weather that in winter has been described as feeling like “iron on stone.” Indeed, the priests seemed to be in retreat from their pioneering mission of spreading religion to a group of people named for the Coppermine River, which bisected the tribe’s hunting grounds. The year was 1913, exactly three years after the Copper Eskimos became some of the very last North Americans to encounter Europeans.

Living above the Arctic Circle had taken its toll on the missionaries. A diary, discovered later by police, would reveal their last written thoughts: “We are at the mouth of the Coppermine. Some families have already left. Disillusioned with the Eskimos. We are threatened with starvation; also we don’t know what to do.” The priests were members of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a group known for some of the Catholic Church’s most remote missionary work. Oblate priests had been offering spiritual solace to the Dog Rib and Hare Skin Indians in Canada’s far Northwest for years. Fathers Rouvière and LeRoux, at the ages of thirty and twenty-eight, were pushing this work to the very edge of the continent. They planned to follow the migrating Eskimos to the sea, live with them, care for them. They intended to build a church and get the Eskimos to come. They wanted to conduct baptisms, and marriages, and funerals. The fact that they spoke little of the native language did not deter them. “There will be some tough nuts up there,” Father Rouvière had said, “but they are too good-hearted to put up much of a fight against grace.”

In fact, Eskimo country did not, on its face, seem to offer promising soil in which to plant the seeds of Christianity. For one thing, the landscape itself offered few parallels to the places where the religion had been born. There were no gardens, no vineyards, no deserts with which to illustrate biblical parables. There were no sheep or shepherds. There was no daily bread. There was no easy way to describe a crucifixion, because there were no trees. There was no notion of “God.” Early translators of the Lord’s Prayer had settled on “Our boat owner, who is in heaven.”1

Where Eskimos had encountered Europeans, mostly to the west, near whaling ports in the mouth of the Mackenzie River, they thought the strangers a bit odd. Among other things, white trappers, missionaries, and police officers seemed to insist on traveling without the skills and companionship of women. Europeans arrived with useful tools, it was true, but most were unable to clothe, feed, or protect themselves. Many of them died of starvation or exposure.

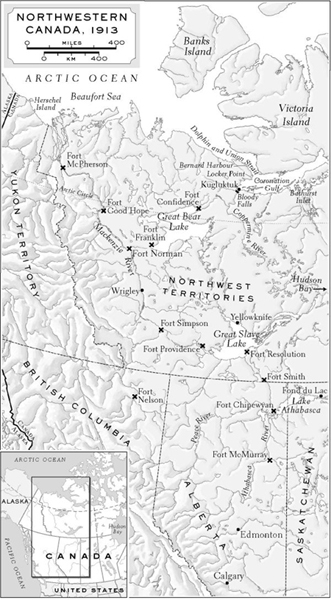

The priests were unbowed by the unlikeliness of their mission. They were favored by their bishop, Gabriel Breynat, who oversaw a region stretching between Hudson Bay and the Alaskan border, and from just north of Edmonton in the south to Victoria and Banks Islands at 72 degrees north—all told, about a million and a half square miles. Breynat, a gregarious man with a twinkle in his eye and an enormous, bushy beard, admired Father Rouvière’s sensitivity, his gentleness, his ability to accommodate adversity. Father LeRoux was a polished, well-educated man who also seemed rugged, physically capable of living in a place that demanded resiliency. The priests and their brethren had spent years traveling from outpost to outpost, building a network of tiny churches across the Northland. But this fall, for Rouvière and LeRoux, things had gotten dicey. Months of hard living and a diet that consisted almost entirely of scraps of caribou meat had left their bodies malnourished and weak. They had been making little headway with the Eskimos. They were utterly frustrated with the Eskimo language. How could they teach about the mysteries of the Immaculate Conception, of Communion, of the Resurrection, when they were frequently limited to communicating with hand gestures? It was hard even to be sure if the Eskimos knew what the priests were doing there. Their simple wardrobes, which at home projected humility and a willingness to live apart from the world of getting and spending, meant nothing here, except perhaps that white men did not know how to dress against the cold. Worse, as inexperienced hunters, they were able to contribute nothing to the survival of the group with whom they were traveling, especially at a time in the season when food was getting extremely scarce. By this point, in early winter, the caribou had all but vanished, and the ice was not yet firm enough to allow for seal hunting. For the Eskimos, the priests, in a very real sense, were just two more mouths to feed. “There is contempt for the white man that no argument on your part can eradicate, or even lessen very much,” another Oblate priest would write. “ ‘Krabloonak ayortok!’ The white man does not know a thing.”2

Fathers Rouvière and LeRoux spent five days with a group of Eskimos at a camp where the Coppermine River dumps into the Arctic Ocean. The time did not pass easily. After quarreling bitterly over the ownership of a rifle, Father Rouvière harnessed his weak body to a sled, Father LeRoux gathered up a couple of dogs, and the odd little team started hiking south. They never made it home.

Two days after the priests began their journey, a pair of Eskimo hunters named Sinnisiak and Uluksuk found the priests struggling along near a stretch of the Coppermine already heavy with history. In July 1771, just two days before he had become the first white man ever to see the Arctic Ocean, the explorer Samuel Hearne had witnessed a scene of overwhelming violence between Copper Eskimos and Chipewayan Indians at Bloody Falls, a dramatic cataract that for centuries had been a favorite Eskimo fishing spot. Arriving at Bloody Falls fifty years to the day later, the doomed British explorer Sir John Franklin stumbled on “several human skulls which bore marks of violence, and many human bones.” Given the rarity of white visitors to the banks of the Coppermine, it seems certain that the two priests would have known about the legend of Bloody Falls. Whether they pondered the story is unknown. What we do know is that the priests also ended up dead. Their livers were removed and eaten. Their bodies were thrown aside, and left to the wolves.

It took months for rumors of the killings to blow far enough south to reach a Catholic mission post. The Royal North West Mounted Police were called in for an investigation that had no precedent. For two years, a handful of young constables used canoes and dogsleds to cross thousands of miles of the continent’s least-charted terrain. It was a dangerous assignment, requiring the patrol to overwinter in the Arctic and face the same challenges that routinely caused the far hardier and more experienced Eskimos to starve to death. Some of the most famous Arctic explorers of the twentieth century, including the anthropologists Vilhjalmur Stefansson and Diamond Jenness, overlapped with the search; they mediated encounters between officers and Eskimos, helped them find their suspects, allowed the patrol to transport the prisoners on board their research vessel.

Once Sinnisiak and Uluksuk had been arrested and carted off to Edmonton for trial, they became instant curiosities, attracting crowds wherever they went. Here, for the first time, city dwellers could ogle two men lifted straight out of the Stone Age. Newspapers swooped down on them, snapping photographs and parsing their every movement for evidence of prehistoric behavior. “More primitive than any race of people to be found in darkest Africa, less touched by civilization than any other humans, the Eskimos offer to ethnologists the most fertile subject for study,” one white “expert” told the newspapers. “If treated well the white man is as safe with the Eskimo as he is anywhere on earth. But anyone who plays them false must expect to die. Death is the only penalty the Eskimo knows.”3

For their part, Sinnisiak and Uluksuk had never dreamed that so many people could exist in one place. They were amazed by the city’s technology. They saw trams held up by wires, and newspapers they could not read but that carried their photographs. An Eskimo translator, taken to a ballet, was seen by reporters covering his eyes at the sight of the half-naked dancers.

When Sinnisiak and Uluksuk entered the Edmonton courthouse, they became the first Eskimos ever put on trial in a white man’s court. The prosecutor in the case lost little time telling the jury that their conviction would send an important message to all native North Americans. “These remote savages, really cannibals, the Eskimo of the Arctic regions, have got to be taught to recognize the authority of the British Crown,” the prosecutor told the jury. “The code of the savage, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a life for a life must be replaced among them by the code of civilization. . . . The Eskimo must be made to understand that the lives of others are sacred, and that they are not justified in killing on account of any mere trifle that may ruffle or annoy them.”4

On the witness stand, Sinnisiak and Uluksuk claimed that the priests had threatened their lives. Father LeRoux had bullied them, brandished a loaded rifle, threatened to shoot. “Any man, whether he is white or black, civilized or uncivilized, is justified in killing another in his own self-defense,” their attorney argued. “Was it not reasonable, considering the extent of their mind, the little knowledge they had of the white race, the two greatest fears they had—fear of the spirits and fear of the white man, the stranger—were they not justified in believing that their lives were in danger?”5

Who was the jury to believe? Even the judge refered to Sinnisiak as a “poor, ignorant, benighted pagan.” There were no witnesses, save the two suspects, and their perspective on life and death in the Arctic was utterly outside the jury’s ken. Forget about their not speaking a word of English. Until three years before they met the priests, they hadn’t even known white men existed. Attorneys for both sides would tell the press the trial was “the strangest that has ever taken place on the continent.”

A question that hovered in the courtroom, and that would haunt the Far North for decades to come, can be boiled down to this: did the priests themselves, in their ravaged state, in their desperation, become murderous? Were they, stripped of all vestiges of their civilized training, reduced to their own brand of savagery? This question prompted still larger questions. Two men from Europe had commited their lives to missionary work in a landscape that was as alien to them as the surface of the moon. What did they imagine their lives would be like up there, surrounded by a vastness that could have swallowed all of Europe and that contained over its entire expanse fewer people than a small French village? How did they imagine the flow of human wisdom and experience? The story of the priests and the Eskimos, and the police investigation and the trials that followed, became a kind of a crucible in which to ponder the history of the North American frontier.