We have now taken the time to examine our own views, engage with curiosity and grace with others, and get comfortable with the often uncomfortable results. If we could continue to engage with politics only on this highly personal and individual level, our work would end here. We spend hours every week exercising these skills with each other. We work through our own limitations and mistaken perceptions. We spend time talking through our shared values and goals. We leave our weekly conversations hopeful and energized.

Then we check the news.

We swipe left on our phones or open Twitter against all our better instincts. We turn on Fox News or turn up NPR, and we’re suddenly, jarringly, back in the arena. Everyone is wearing their jerseys, and no one is winning. We’ve made no secret throughout this book that we feel our media environment is in part to blame for the toxic polarization currently plaguing our country. We don’t mean any of this “fake news” nonsense. We mean that the media reinforces all our worst instincts and makes money while doing it. An “us versus them” (or left versus right or Democrat versus Republican) narrative is the easiest story to tell, so they tell it over and over again with abandon. This narrative is also the one most likely to tap all our most tribal instincts and get us clicking, watching, and sharing to drive advertising revenue.

However, ignoring the media is simply not an option for us, and we don’t believe it should be for you either. The single question we receive most often is: How do you do it? How do you read the news and talk politics all the time without losing your mind?

Listen, we get it. The news can be depressing. It can be frustrating. It can be infuriating. It can be all three at the same time and then some. We understand the instinct to shut it all out and go tickle the nearest baby until you forget Lester Holt even exists. We also should be honest and admit we have both gone on news fasts when we needed to plug back into the perspective that time with family, friends, or yourself can provide.

Disengaging with the news is not a real solution. There is no way to permanently ignore the news, and we shouldn’t want to. Being an informed citizen is part of our sacred duty as participants in our democracy. We are our sisters’ and brothers’ keepers, and we owe it to one another to pay attention and show up.

The solution is not disengaging. It is learning how to engage with the news in a smart and thoughtful way. Many of us live inside news echo chambers populated by sources that are not credible and that are sometimes manipulative. We learned during the 2016 election that foreign powers were easily able to convince Americans that phony accounts distributing false stories were as credible as the Wall Street Journal or Washington Post. Being in an echo chamber is not a character flaw. It’s a systemic problem. According to the Pew Research Center, almost two-thirds of us get our news from social media. The survey found that 67 percent of American adults were “somewhat” reliant on social media platforms for their news.1

As even the least tech-savvy among us are beginning to understand, social media platforms’ technology is built on algorithms. Computers use algorithms to solve problems. The problem social media platforms are trying to solve is how to gain and keep your attention. The algorithms take in data based on what you click, what you like, and what you share. They then serve up more content that aligns with your interests to keep you clicking, liking, and sharing away.

In other words, the system is built to please you, not to challenge you.

As a result, we all see more and more and more (and more and endlessly more) news-related content that confirms our worldview and reinforces our ideas (including that the world is a scary or threatened or failing place). It’s not only the stories we see. In a perfect world, social media would help us have conversations across economic and racial and social lines. It would allow us to expand our conversations and our horizons. In practice, we build social circles consisting of people who look and think and act like us. We share stories that they like and comment on and share. We, in turn, read stories they share and like, and it’s all a vicious cyclone of input that makes us feel that we are right (and popular! And smart! And relevant!). These interactions push all our pleasure triggers, but they are not based on real connections. Meaningful connections with both people and news sources that challenge you lead to deeper self-awareness and growth, not the shallow satisfaction of feeling momentarily validated.

These online echo chambers are dangerous, and they make starting or continuing grace-filled political conversations difficult if not impossible.

We have to exit our echo chambers.

In this chapter we offer accessible challenges to empower people to step outside their own bubbles by engaging with new information sources. We discuss how to talk about politics on Facebook and Twitter in ways that are actually productive. We offer up empathy mapping as a tool for understanding how someone who disagrees with you views the world. We provide suggestions on changing your news sources and interacting with family members, in person and in writing, when you passionately disagree. We discuss the role of politics in our pulpits, workplaces, and church families. This chapter is essential for surviving the holidays and maintaining your friends online and in real life.

• • •

It was in the aftermath of the 2016 election that we realized our desires to exit our own echo chambers. Our listeners were also clamoring for ways to push back against a social media environment that left them feeling empty and disconnected. So, only a few weeks after the election, we launched the Exit the Echo Chamber challenge—a weeklong event with our Pantsuit Politics community. Every day we posted a different challenge that pushed us outside our own echo chambers on social media, in real life, and in the news media environment.

The daily challenges were:

Day 1—Take a selfie explaining why you want to exit the echo chamber.

Day 2—Read three articles from news sources you don’t usually read.

Day 3—Have a conversation in real life with someone who voted differently than you.

Day 4—Send a letter or email to someone you’ve disagreed with politically.

Day 5—Compliment the other side.

Day 6—Draw an empathy map for someone in another political party.

Day 7—Take action.

First, we wanted everyone (including ourselves) to think about why they wanted to exit the echo chamber by posting a picture of themselves and explaining their reasons for exiting. Much like how the first rules of this book ask you to examine yourself and your motives, we decided the first step of any good challenge is asking yourself why you are doing it in the first place. Sarah posted that she was exiting the echo chamber “because confirmation bias is a threat to our democracy.” Beth posted that she was exiting the echo chamber because “narcissism doesn’t equal news, and arrogance doesn’t equal analysis.” We had listeners post that they wanted to exit the echo chamber for reasons that reflected concerns about the media, the political system, and even themselves:

“Because no political party has a monopoly on good ideas.”

“Because writing off the other half of the population is getting us nowhere.”

“Because I’m guilty of thinking I know it all, and there is so much more to learn.”

“Because I believe empathy is the key to progress.”

Next, we encouraged everyone to swap their news sources. We provided a list of podcasts, publications, and writers from both the Left and the Right, and we asked our listeners to swap. Now, this didn’t mean we wanted our liberal listeners to engage in a four-hour Rush Limbaugh marathon. We agree with Julia Galef, cofounder of the Center for Applied Rationality, and her recommendation to engage with news sources that aren’t directly opposite your worldview and approach—because if you do seek out sources that directly oppose your thinking, you can end up hardening your opinions instead of exploring them. She recommends engaging with news sources through the lens of liberal/conservative and emotional/analytical. If you are analytical and progressive, try an analytical and conservative news source. If you are conservative and emotional, try a more emotional but also progressive source. For this challenge, we thought it was important to list not the far ideological outreaches of our media environment, but rather sources that are mostly calm and intellectual.

However, even these sources were a challenge at first to many of our listeners. Kyla wrote us about her experience listening to The Federalist Radio Hour podcast: “The first [episode] confirmed my worst suspicions of conservatives.” It wasn’t an immediate revelation. Most of us are decent at articulating the basics of the other side’s opinions, even if we lean heavily on emotion and hyperbole. It is only through repeated exposure, helping us to lower our guard and start to really listen, that we can find pieces (even small ones) that we understand and even agree with. That was Kyla’s experience with The Federalist Radio Hour. She wrote us that she was taking a slow approach to the entire challenge and spent more than a single day on exposing herself to other news sources. She kept listening to The Federalist Radio Hour podcast and eventually moved beyond her initial dislike. “The second two were okay, but the one I listened to today actually made some sense and was very timely after having just listened to your podcast and the discussion about how we get our news and what’s newsworthy and what’s real journalism.”2

For day three, we asked our listeners to exit the echo chamber by having a real-life conversation with someone they disagree with politically. We kept the mission achievable. The goal was not to score points or convince anyone, but rather to understand why they feel the way they feel.

Here were the tips we offered to our listeners as they tackled this challenge:

• Don’t have a stake intellectually, emotionally, or otherwise in the other person’s thoughts and feelings. Make “you do you” your mantra.

• When you feel yourself reacting negatively to something you hear, hit pause in your mind. Ask yourself (1) “Why am I reacting this way?” and (2) “What could this conversation be like without my reaction?”

• If you aren’t finding common ground, that’s fine. Channel your inner talk-show host and conduct a kind, respectful interview of the person. Ask things like: “When did you first start to think about the election that way?” “Have you always voted for this party?” “When you think about future elections, what’s really important to you?” “What do you think the biggest challenge for the next four years will be?” “What do you think will be important to shaping the outcome of the midterm elections?”

• Don’t make assumptions, and recognize when the other person is making assumptions. When you realize the other person is making a statement based on assumptions about you, call that out: “I understand why you’d think that I support XYZ, since many people in my party do. But my perspective is different.”

• Keep it calm. If you’re talking to someone who wants to amp the conversation up, just don’t go there. Instead, say things like: “I don’t know what you mean when you say [inflammatory term]. Can you share what that means to you?” “Hey, I’m trying to learn from our conversation, not debate. So can you say more about that?” “Do you mind if I take some notes while we talk?” (We don’t know why, but trust us! When you start taking notes, it reminds people that having some level of civility is important).

What we found most fascinating from this day of the challenge was that our listeners seemed to fall in two diametrically opposed camps. Either we had listeners who had trouble finding someone they disagreed with politically because they lived in such an echo chamber, or they had zero trouble finding someone they disagreed with politically because they were the only person in their family or even community who had voted for their candidate. We wondered afterward if maybe both are a matter of perception more than anything. While we have no doubt that the political silos social scientists have spilled gallons of ink over exist, perhaps they are self-perpetuating in a way. We assume everyone agrees when there are those who may not, but feel intimidated to share their true thoughts. Or we never challenge each other enough to see there are areas of disagreement, something that would surface if we weren’t merely patting ourselves on the back about how right we are most of the time.

For day four, we asked our listeners to write a letter to someone they had passionately disagreed with about politics in the past. We wanted people to move beyond the surface-level discussions that happen when someone is a casual acquaintance or Facebook friend. We didn’t want people to just recognize where there was honest disagreement around them; we wanted them to dive deep into historical areas of conflict that they had been avoiding in an effort to “keep the peace.” This wasn’t intended to force people to fight with those they loved most, because this wasn’t about fighting. This step was about prioritizing our closest relationships while at the same time prioritizing political debate.

We need to remember—to relearn—what it’s like to see the world through the eyes of someone we love even when that is difficult. We need to remember what it is like to disagree with dignity and respect, and we believe that is easiest to do with those we already know and love and trust.

One of our listeners sent an open and vulnerable letter to her mother, whom she had disagreed with over abortion.

Hi Mom,

I’ve been thinking about this for a few days, and I really appreciate that we were able to talk about the presidential election a little bit the other day. I really appreciated your understanding of my position, even though I’m pretty certain that we voted differently.

There was something I wanted to invite you to reconsider for the future. You mentioned during our conversation that, while you’re not a single-issue voter, you had a hard time stomaching Hillary Clinton’s position on late-term abortions.

When I watched the third presidential debate, I heard Donald Trump describe a late-term abortion as something horrific that happens with a viable baby days before delivery, and I thought to myself, “That sounds abhorrent and shouldn’t happen.” And from what I’ve been able to tell, that does not happen. Viable babies are not aborted days before a woman’s due date.

On this issue, I think the majority of people would agree that a woman who changes her mind or gets cold feet thirty weeks into her pregnancy should suck it up, and if she doesn’t want her baby, she should put it up for adoption. But, I think that the reality of the situation is a lot closer to what Hillary Clinton described in the debate. Someone who is considering terminating a pregnancy after twenty weeks is facing an impossible choice. These are people who have discovered their baby has a terrible birth defect—maybe their brain isn’t developing properly—and they have to decide if they want to carry the baby to term and have their baby die shortly after birth or be kept alive by machine and suffer greatly, or go ahead and let it go and begin the grieving process. Or it’s someone who discovers that they have cancer, and they have to decide if they want to begin treatment, which would kill the baby, or delay treatment, which could kill the mother.

I find these realities terrifyingly close to home. I can put myself in these women’s shoes. I have two little girls who need a mother. Would I really be willing to leave Daniel to raise three children by himself? I know that I would jump in front of a moving vehicle, wrestle an alligator, or do whatever it took to protect my children. But in that situation . . . I would want that to be my choice, so that whatever happened, I could put myself and my family in God’s hands and go from there. I think that is what the “pro-choice” position is . . . to me, it’s a Republican ideal—we have to trust individuals, families, and their doctors to make these heart-wrenching choices together.

I feel like the Republican party has lost its way on this issue by making it so simple: “Protect the life of the baby.” We need to support and protect family and women’s health. In Texas, the Republican legislature effectively defunded Planned Parenthood, and the maternal mortality rate in Texas jumped 600% because low-income women didn’t have access to prenatal health care and screenings. When mothers die having babies, that’s bad for babies and families. I also feel like the Republican party has picked another fight in opposing giving women access to birth control under the Affordable Care Act. It just seems like if women who don’t want to be pregnant aren’t getting pregnant, then they won’t get abortions. That seems like a win-win solution!

Anyway, I’ve been trying to pay attention to both sides of the aisle lately, and there are a lot of Republican and conservative ideas that I would really like to support, but I am perplexed at why the party has chosen Planned Parenthood as a hill to die on. Why do they feel like women will start waiting until the absolute last minute to terminate their pregnancy if only we give them a chance? I’m entirely certain that any woman who feels her baby kick isn’t going to end that lightly.

I just wanted to share my thoughts on this with you, because I know you love children, you support families, and you care about people. And I think that our politicians need to know that their constituents are able to handle the complexity of these issues, so they have the freedom to compromise without getting booted out of office. I hope this gives you some food for thought and room for grace on the issue. I love you, and I’m really looking forward to seeing everyone this weekend!3

When we asked her if and how her mom responded, she reported back that her mother had in fact responded, and she had initially been disappointed that her mother wasn’t more responsive and willing to see her side of the issue. “But now that I revisit it, I feel like she gave a little more room than I initially remember (or at least more than is typical for her). I kind of struggled with her response, because who wouldn’t secretly hope that such a nice letter might persuade someone not to vote for Donald Trump over the issue of abortion if they had a do-over? But I think that thing you say all the time about ‘rubbing each other’s rough edges off’ really applies here.”4 We were so encouraged by this response, because it’s exactly what we’ve often found in our own exchanges. The first attempt at revisiting difficult topics is harder for us and doesn’t always lead to the response we want (okay, it never does initially). That’s exactly why they present opportunities for growth. This listener had to face her own fears and be honest about the way she had shut down the conversation in the past without really listening. She had to hear her mother’s genuine concerns for babies and consciously prioritize their relationship, not political conversion. When we do this and reflect on our own thoughts and those of others, we will find real opportunities for growth in ourselves and our relationships.

On day five, we asked our listeners to join us in a weekly segment of the show called Compliment the Other Side. One of the central values of our podcast is that both parties serve purposes and contribute important ideas. In order to live out that value, we each take a moment in our Tuesday episodes to compliment a member of the other party. We have complimented senators speaking their minds, governors solving big problems, state representatives and local officials working hard on everything from school lunches to tax reform. When we asked our listeners to take part, they seemed to have lists on hand and were ready and willing to look beyond the national names getting all the attention (and perpetuating our polarization) to people in their own communities and states doing inspiring work. Complimenting the other side is one of the most refreshing parts of our podcast, and it became a favorite moment in this challenge.

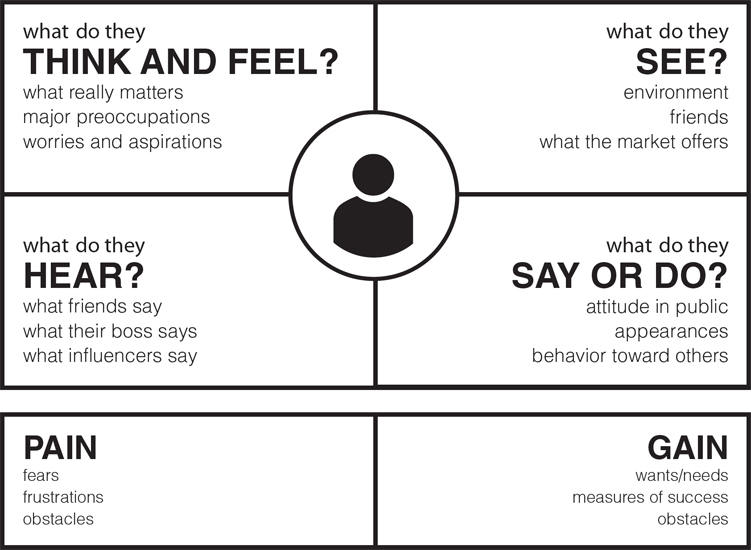

On day six, we took a different approach to our exploration. We often talk about having increased empathy for the other side, and we felt that exiting the echo chamber only to hear ideas and emotions you could not understand would not be a positive step forward. Sarah first came across the idea of empathy maps while listening to a sales podcast. Dave Gray, a management consultant and author, originally created empathy maps as a tool to help sales teams understand their customers. Sarah was also reading Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. The book is author and sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild’s effort to exit the echo chamber by moving to rural Louisiana. Sarah started thinking about what Hochschild described as “empathy walls” and how to climb them in our political discussions. Empathy maps seemed like a good approach.

An empathy map is a tool used to gain deeper insight into a point of view. Empathy means that you can both intellectually understand someone else’s feelings and vicariously experience those feelings. We asked our listeners to identify one political opinion or group that they struggled to understand and to use the empathy map to gain insight into that point of view. Creating an empathy map allows you to tune in to another person by considering what that person thinks, sees, hears, and feels. You also consider the person’s “pains and gains.”

Many of our listeners told us that actually putting pen to paper and thinking through the perspective of the other side forced them to push themselves past the usual emotions of the argument. Many looked at editorials and reached out to friends and family to really flesh out the areas with which they struggled to empathize. Like every other day’s challenge, the empathy map wasn’t a cure-all. None of these challenges are a magic pill in and of themselves. Instead, they help bit by bit to lay the foundation for better understanding of both ourselves and others.

On the final day of the challenge, we asked our listeners to take action. The best way to exit the echo chamber of opinions is to exit in the purest sense of the word. Stop talking and start doing. While we believe wholeheartedly in the power of dialogue, there is a time when closing your computer or putting down your phone and stepping out into the real world is the best way to exit the echo chamber. Action can take many forms, and we encouraged our community to find the action best suited to their time and energy. We had listeners call their congressional representatives for the first time. We had people attend local city council and school board meetings. We had people sign up for elected-official training programs. Whatever action they took, the willingness to stop politically existing solely inside an echo chamber was key to exiting for good.

YOUR PRACTICE

Take the Exit the Echo Chamber challenge yourself! Our listener Kyla suggested a slow version: “I felt I needed to put a lot more planning and thought into each step than I could manage in a day (or two!).” We love that, so feel free to dedicate as much time as you need to each step. Be easy on yourself and others. We exist inside an intense media environment, reinforced on so many levels by the ways in which we sort ourselves socially in real life and online. Take your time and give yourself lots of grace in the process. Here is a list of suggestions to get you started on your own exit:

• We still love to hear from people exiting the echo chamber. So take a selfie explaining why you want to exit the echo chamber, include the hashtag #exittheechochamber, and tag us on your favorite social media platform.

• Read three articles from news sources you don’t usually read.

• Have a conversation in real life with someone who voted differently than you.

• Send a letter or email to someone you’ve disagreed with politically.

• Compliment the other side. This is another great social media post and encourages a completely different energy than you usually find surrounding politics in this medium.

• Draw an empathy map for someone in another political party.

• Take action.

CONTINUE THE CONVERSATION

From a spiritual perspective, we are specifically called to exit our echo chambers. Think about the life and practices of Jesus. He shared messages that completely shook many religious leaders’ understanding of faith. He wrecked the temple to point out its misuse. And he specifically reached out to people otherwise shunned by society. We love telling our children the story of Zacchaeus specifically because it’s an exit the echo chamber moment. There are myriad reasons to reach beyond the people and sources that make us comfortable so that we can test and refine and enhance our own understandings.

1. An echo chamber can be defined in many different ways—all of which have their own political repercussions. How often do you engage with someone of a different race or economic status? If you are married with kids, how often do you talk with single people or those who have chosen to be childless?

2. What are your fears (if you have any) about engaging with someone outside your political perspective?

3. How do your usual news sources make you feel? Before you turn on the TV or click through to the site, do you feel anxiety or geared up in some way, or can you approach it with a more neutral emotional position?