CHAPTER

001

Encounter at Goldeneye

Goldeneye, Ian Fleming’s legendary retreat in Jamaica, sits atop a bluff with commanding views of a cerulean-blue Caribbean. The former British naval intelligence officer first visited the island with his lifelong buddy, Ivar Bryce, when they participated in a U-boat conference during WWII, and Fleming immediately trained his sights on returning.

As Bryce recounted in his memoir, You Only Live Once, Fleming told him: “I have made a great decision. When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica and lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books. That is what I want to do, and I want your help, as you will probably get out of the war before I can. You must find the right bit of Jamaica for me to buy. Ten acres or so, away from the towns and on the coast. Find the perfect place; I want it signed and sealed. Please help.”

After the war, Bryce got to work. The first time he set eyes on a secluded cliffside property on the north coast, he knew he’d found Fleming’s perfect place. Bryce bought the 14-acre property for 2,000 pounds—about $8,300—on the spot.

In 1946, Fleming set out to build a modest one-story house on the site, a former donkey race course. As Matthew Parker recounted in his 2015 biography Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born, the area was also known as Rock Edge and Rotten Egg Bay. Fleming specified that the three-bedroom bungalow be simple, and that the windows have no glass so he could live as much outdoors as indoors and birds could fly in and out as they pleased.

He named the place Goldeneye, not after the duck of the same name but after a plan he’d developed for the defense of Gibraltar during the war, and after one of his favorite books, Reflections in a Golden Eye, the 1941 novel by Carson McCullers.

It was the perfect spot for a man who loved watching birds, from the kling-klings (Jamaican grackles) that hung out on his patio to the array of hummingbirds that darted back and forth between the hibiscus and bougainvillea Fleming had planted.

Here, from mid-January to mid-March for thirteen winters, Fleming wrote his world-famous 007 novels while on paid leave from his post as foreign news manager for the Sunday Times in London. Here, he entertained such celebrities as Graham Greene, Errol Flynn, Truman Capote, Katharine Hepburn, British prime minister Anthony Eden, and Princess Margaret.

Kling-klings (Jamaican grackles) have been getting into mischief at Goldeneye for as long as anyone can remember. Fleming featured them in The Man with the Golden Gun. Photo by author

Ian Fleming’s bulletwood desk at Goldeneye, where he wrote his 007 novels from 1952 to 1964. Mark Collins photo, courtesy of Island Outpost

And here, on February 5, 1964, unexpected visitors appeared at Fleming’s front entrance.

The timing couldn’t have been better, at least as far as Fleming was concerned. On that sunny Wednesday morning, a film crew from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was interviewing the man with the golden typewriter. For Fleming, a master of self-promotion, the interview dovetailed nicely with the publicity for his latest 007 projects. You Only Live Twice, his eleventh spy novel, was less than two months from publication. Goldfinger, the third screen adaptation of his 007 thrillers, would arrive that September.

Fleming’s housekeeper, Violet Cummings, greeted the visitors, an American couple in their sixties, on the grass-covered drive that led from the main road to the bungalow. The man, dressed in light slacks and a loud patterned shirt that shouted “tourist,” asked if the author was home. Cummings hurried inside and interrupted Fleming’s interview, exclaiming that “Mister James Bond” was there to see him. Fleming thought she was joking at first, then agreed to meet his guest. The thriller writer was about to meet the man whose identity he’d secretly stolen off the dust jacket of a book on his shelf twelve years earlier. At the scene of the crime.

When Ian Fleming greeted Jim Bond and his wife, Mary, that February morning in 1964, he wore a short-sleeved black guayabera shirt, matching slacks, and open-toed sandals that he had chosen for the TV interview. According to Mary Wickham Bond in her 1966 memoir, How 007 Got His Name (“by Mrs. James Bond”), Fleming’s brow was “beaded with perspiration, his fair hair damp and curling, British fashion, behind his ears.”

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation interviewed Ian Fleming at Goldeneye on the same day that Jim Bond arrived unexpectedly. CBC Licensing

Why might a cool customer like Fleming break a sweat, beyond the camera lights? He didn’t know if this visitor who called himself James Bond was the genuine article and—if he was—why he had shown up unexpectedly.

As Fleming led the couple past the TV crew’s station wagon to his one-story home, he turned and wondered aloud: “You’re not coming to threaten me with a libel case, are you?”

Mary Bond laughed. “Of course not. I want to see where the second James Bond was born.”

The fifty-five-year-old Fleming brought his guests into the house and a main room filled with film cameras, sound equipment, lights, and a television crew of four.

In How 007 Got His Name, Mary described what happened next:

“Mr. Fleming, tickled with the drama of the situation, lived up to his penchant for the unusual. He flung out his arms and exclaimed, ‘This is a bonanza for the CBC! I never saw the man before in my life, but here he is, the real James Bond, stepped right into the picture!’ He turned to Jim and said, ‘This’ll sell even more of your books and mine!’”

Bond and Fleming met just once, at Goldeneye, in 1964. Photo by Mary Wickham Bond, Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department

The film crew followed Fleming and the Bonds outside to the terrace, where they stood at the edge of the cliff and looked down to a perfect sun-drenched beach. The main camera man was hopping about in the shrubbery, quietly filming the three of them. Bond, quite oblivious to what was going on, kept talking to Fleming about who knows what. Fleming told him to talk for the camera, but Bond couldn’t have cared less.

“A lot of birds were flying about and one could sympathize with Mr. Fleming’s next question,” Mary wrote. “‘What kind of birds are they?’ he asked Jim. After all, couldn’t any handsome stranger drop in and pass himself off as James Bond?”

“Cave swallows,” Bond replied. “A very common species in the Antilles. Do you see the square shape of the tail? If you look closely you’ll see a chestnut rump.”

Fleming nodded, suppressing a smile. The birdman was for real.

Jim Bond immediately got something off his chest. As he told Pete Martin of the Sunday Bulletin Magazine later that year, “I confessed to Fleming right off when I met him: ‘I don’t read your books. My wife reads them all but I never do.’ I didn’t want to fly under false colors. Fleming said quite seriously, ‘I don’t blame you.’”

When the film crew left for lunch, the Bonds took a swim with Fleming and his wife, Ann, sipped rum punch, and dined on a traditional Jamaican dish made of saltfish and the national fruit, ackee, which when cooked looks like scrambled eggs and tastes like a buttery potato.

Joining the two couples were the Flemings’ house guests from London, Hilary Bray and his wife, Ginnie. Bond was in good company. Fleming had appropriated Bray’s name for a character in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, published the previous year.

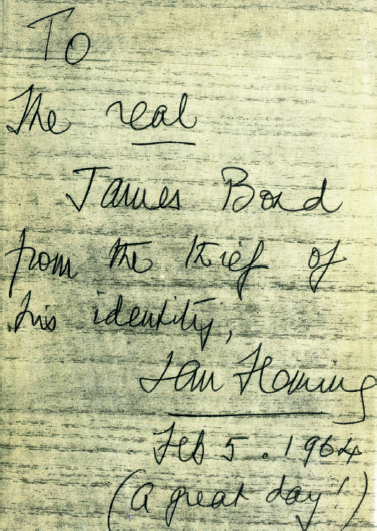

Fleming left no doubt about how he got the name for 007 when he inscribed a first edition of You Only Live Twice to “the real James Bond.” Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department

As Mary Bond recounted in How 007 Got His Name, during lunch, Fleming encouraged her, a published novelist, to write about her husband’s adventures in the Caribbean someday, saying that “whatever he actually did outshines anything I’ve made my James Bond do.”

The visit ended a couple of hours later with Bond signing the Goldeneye guest book. Fleming told Bond he deserved a page all his own, adding: “And write it big!”

The American then received a copy of the bestselling author’s latest spy novel, inscribed boldly on the fly page: “To the real James Bond from the thief of his identity, Ian Fleming, Feb. 5, 1964 (a great day!).”

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation says the outtakes from that day that include the Bonds no longer exist, but Mary took a snapshot of the two men. They are standing at the front entrance, with two of Fleming’s servants waiting in the shadows. Jim Bond stands more than six feet tall, several inches taller than his host, but Fleming has chosen to stand atop the front step, making his guest appear shorter. And although Fleming had suffered a major heart attack three years earlier, he holds a cigarette in his left hand. Both men are smiling. Fleming looks the part of a world-famous author. Bond looks like some guy on vacation who had happened by.

Seeing the contrasts between the bespectacled American ornithologist and the dapper British spy novelist in the photo, it’s hard to imagine the two had much in common. Although their paths never crossed again, their lives shared some similarities. Both men were born into ultrawealthy families at the start of the twentieth century. As youngsters, both were intrigued by nature. Both lost a parent when they were young. Both spent their teen years in British boarding schools. (Bond developed a bit of a British accent there—one that stayed with him the rest of his life and led him to pronounce such words as “mobile” like a Londoner instead of a Philly boy.) Both went to college in England and were mediocre students. And after following in their fathers’ footsteps, each of them pursued financial careers soon after college.

Perhaps most important of all, both men became authors and found ways to spend their winter months in the West Indies doing what they loved. Fleming created his most lasting work while seated at a typewriter at a red bulletwood desk at Goldeneye. Bond visited dozens of remote islands, equipped only with a pair of eagle eyes and a double-barreled shotgun.

As Morris Cargill recounted in the book Ian Fleming Introduces Jamaica, both Fleming and Bond said how much they’d enjoyed that February day. Fleming remarked about the Bonds: “They couldn’t have been nicer about my theft of the family name. They said it helped them get through customs.”

Hilary Bray wrote to the Bonds: “It was a red-letter day for Ian, as for everyone else. He used to reflect on it happily. And when he got back to England he used to relate it as—Goldeneye, the story of the year, 1964. I don’t think anyone considered it his last Goldeneye, though [his days] were numbered.”

The encounter in Jamaica has become part of 007 lore. Fleming’s twelve spy novels and two short-story collections have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide, but only a few have sold for as much as the book that Fleming inscribed to Bond. A first edition of Moonraker, signed by Fleming to Raymond Chandler with the latter’s occasional hand-jotted comments in the margins, went for $102,000 at auction in 2004. Four years later, the first edition of You Only Live Twice that Fleming inscribed to Bond sold at auction to an anonymous bidder for $82,600 (see chapter 007).

As things turned out, the thriller writer, Goldeneye, and the ornithologist also had second lives, and that inscribed copy has taken on a mysterious life of its own. Fleming died after a heart attack in August 1964. According to biographer Andrew Lycett in Ian Fleming, his last words, directed to the ambulance attendants on the way to the hospital, were vintage Fleming: “I’m awfully sorry to trouble you chaps.”

But his legacy lives on in the $8 billion 007 empire anchored by the longest-running franchise in movie history. Over the past half century, the Fleming estate has hired five authors to write more than two dozen James Bond thrillers.

In 1976, Fleming’s estate sold Goldeneye to Jamaica’s Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records and the man who introduced the world to Bob Marley and reggae. Blackwell had shown the property to Marley, thinking that the global recording star would want to buy it. When Marley declined, Blackwell bought it himself, changed the name to GoldenEye with a capital E, and turned it into one of the most exclusive resorts in the world. While visiting Blackwell at GoldenEye, the pop singer Sting wrote “Every Breath You Take,” a song not about love and devotion but an obsessive stalker. Several years later, Bono and the Edge, of the rock band U2, wrote the theme to the seventeenth 007 film there, naming it “Goldeneye.”

The property is now a 52-acre destination for the very wealthy. A stay in the Fleming Villa, complete with two satellite cottages, swimming pool, private beach, and tropical garden, starts at more than $5,800 a night. The resort is a few kilometers from two other landmarks: James Bond Beach and Ian Fleming International Airport.

As for the ornithologist whose name became more famous than he was, “the Real James Bond” died nearly a quarter century after Fleming, at age eighty-nine. Over those final twenty-five years, the proper Philadelphian increasingly regretted the 007 connection, especially after Goldfinger and Pussy Galore landed in American movie theaters and secret agent Bond went from passing fancy to cultural icon.

This portrait of a young Jim Bond was painted by his uncle, noted artist Carroll Sargent Tyson Jr. Courtesy of David Contosta