CHAPTER

005

Birds of the West Indies

On the shelf above my desk are a dozen books of various shapes and sizes titled Birds of the West Indies. Together they weigh 20 pounds and span 12 inches, 4,000 pages, and more than 125 years from end to end.

Two immense volumes serve as bookends and could also serve as doorstops. One is a textbook by ornithologist Charles Cory published in the late 1880s; the other is a large-format photography book by well-known conceptual artist Taryn Simon published in 2013. In between are ten books—seven authored by Jim Bond—whose various incarnations are a study not only in the advances in ornithology, birdwatching, and publishing, but also travel and technology. As far as birdwatchers are concerned, the Bond books, and more recently their successors from Princeton University Press, are the real deal.

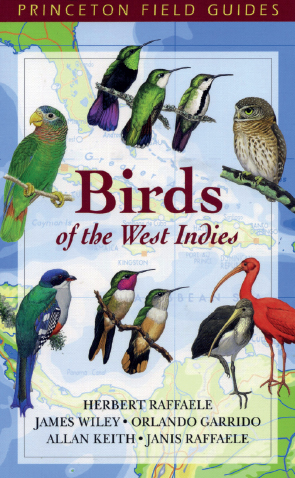

Bond’s book was printed in eight or more editions (depending who’s counting) over nearly six decades, an incredible run. It was finally overtaken in 1998 as the definitive birding book for this region by Princeton University Press’s Birds of the West Indies, by Herbert Raffaele and a team of four other birding experts and two illustrators. At 512 pages, this identification guide is far more exhaustive than Bond’s 1936 original edition or the many that followed.

And the tradition continues. Princeton University Press is publishing an updated version of Raffaele’s 2003 book in 2020.

Here are the books, each fascinating, in chronological order by date.

Birds of the West Indies, 1889, by Charles B. Cory, published by Estes & Lauriat. At 328 pages, this hardcover book with two maps and a smattering of black-and-white illustrations was clearly designed for the bookshelf, not the field. All the species are under their Latin names, so that if you were looking for a description of, say, a Cuban tody, you were in for a lot of looking. When his description of the tody refers to “the faint whitish tippings when held to the light,” you can be sure he was more accustomed to viewing birds on trays than in trees.

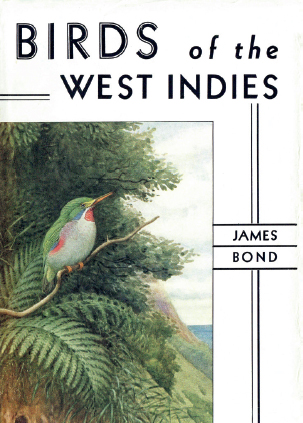

Birds of the West Indies, 1936, by James Bond, published by the Academy of Natural Sciences. Hard cover, 460 pages, with a map on both endpapers showing voyages taken and islands he visited in 1935, plus 159 line drawings by Earl Poole and one color illustration of a Cuban tody.

This is the alpha of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies, and the first to cover nearly all the nonmigratory birds found in the West Indies. It was as much a classic ornithology text as a field guide. It was published two years after Roger Tory Peterson’s classic A Field Guide to the Birds and paled by comparison—the dense descriptions and the single color plate of a Cuban tody could not compare with Peterson’s handier volume with four-color plates of multiple birds.

Nonetheless, this first edition, complete with iconic white dust jacket, is rare and worth thousands of dollars. By all authoritative accounts, it was this edition that prompted Fleming to name his secret agent for James Bond sixteen years after it was first published.

Charles B. Cory wrote the first Birds of the West Indies in 1889. Public domain

The first edition came in two bindings. One was bound in gilt-stamped green cloth with small imprint lettering blocked on the spine. The other is gray-green cloth with large imprint lettering and the word “of” stamped on the spine in a large font.

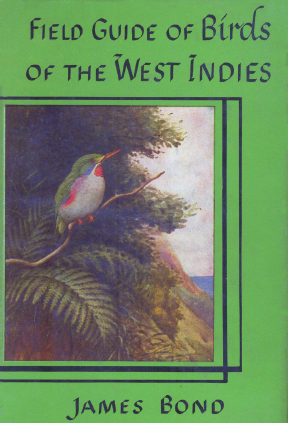

Field Guide to Birds of the West Indies, 1947, by James Bond, published by Macmillan Company. Hard cover, 258 pages, featuring 211 line drawings by Earl L. Poole.

This second edition is far more compact and more in keeping with a modern field guide. On the dust jacket’s front flap is a blurb that captures the book’s appeal: “Whether you are an ornithologist planning a field trip to the West Indies or a globe trotter anticipating a pleasure trip to these beautiful islands, you will want to tuck this little book into your luggage for quick reference. . . . Its primary purpose is to enable the reader to identify the various birds known to inhabit the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles—including the Cayman and Swan Islands—and the Lesser Antilles.”

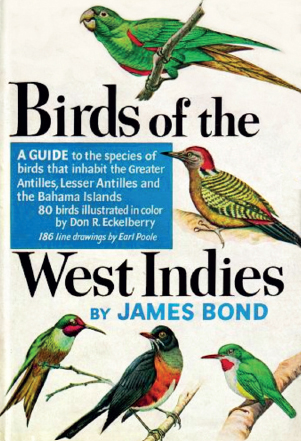

Birds of the West Indies, various editions from 1960 to 2002, by James Bond, published by Collins and Houghton Mifflin. Hard cover, 256 pages. Featuring eighty full-color illustrations by Don R. Eckelberry on eight plates and 180 line drawings by Earl Poole.

Front of the dust jacket for Bond’s 1936 Birds of the West Indies. Courtesy of Jack Holloway

Front of the dust jacket for Bond’s 1947 Birds of the West Indies. Author’s collection

There was a new publisher for the 1960–1961 edition, and also a British edition, and an overhaul that made it far more practical to use in the field. The two editions have different dust jackets.

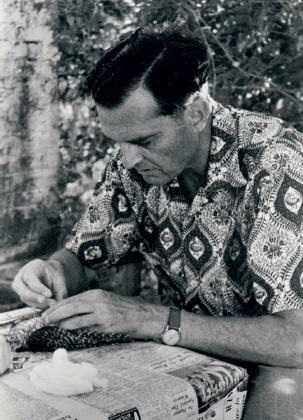

The 1961 American edition features a photograph by Mary Bond on the back of the dust jacket. James Bond is wearing a brightly patterned, short-sleeved shirt that looks identical to the one he wore when he and Mary visited Ian Fleming in 1964. What’s extraordinary is that Bond is skinning a European cuckoo. It might be the only field guide featuring a photo of its author with a bird that he likely killed.

The later editions were essentially the same, with minor variations, but good luck trying to figure out which edition is which. There was no third edition, for example, but at least three fifth editions, including one in 1995 published by Easton Press that was retitled Birds of the Caribbean. Its leather cover has gold lettering and touts its affiliation with the Roger Tory Peterson field guides. On the front cover, James Bond is identified in tiny type—by his last name only.

Birds of the West Indies, 1998, by Herbert Raffaele, James Wiley, Orlando Garrido (Bond’s longtime colleague in Cuba), Allan Keith, and Janis Raffaele, published by Princeton University Press and Christopher Helm, London. Hard cover, 512 pages. 86 color plates.

This hardcover identification guide, published sixty-two years after Bond’s first Birds of the West Indies, is part of a series of old-school Helm Identification Guides and, at almost 3 pounds, a chore to bring into the field.

Front of the dust jacket for Bond’s 1961 Birds of the West Indies. Courtesy of Jack Holloway

Back cover of the 1961 edition featured Bond skinning a European cuckoo. Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department

As with other guides in the series, detailed introductory sections are followed by the plates and information on identification, local names, voice, status, range, habitat, and nesting. A locality checklist provides an at-a-glance, island-by-island guide to the distribution and status of every species.

Raffaele became interested in the birds of the Caribbean when he was eighteen, and later took a trip to Puerto Rico using Bond’s book as his field guide. “Before I left, I went to my local library in Jamaica, Queens, and went straight to 598.2 on the nonfiction shelf—I knew all the birding books began with that Dewey decimal number—to look for a book on the birds of the region,” Raffaele recalls. “And Bond’s book was the book I found. I said, ‘Wow, just what I need.’”

Once Raffaele got to Puerto Rico, he was thrilled to find all the birds illustrated in Bond’s book, but he had trouble identifying small finch-like birds called grassquits because “all that Bond had illustrated was the glamorous stuff.”

Raffaele decided to write his own field guide to Puerto Rico. It was first published in 1983, followed by his Birds of the West Indies, the ultimate guide for birding in the Caribbean and a major step in the ornithological literature of this region.

Birds of the West Indies, 2003, by Herbert Raffaele, James Wiley, Allan Keith, Janis Raffaele, and Orlando Garrido, published by Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford. 216 pages. This field guide is a classic example of less is more. Weighing two-thirds less than the previous version, it’s filled with useful information and illustrations for identifying birds, including an overview of how common or rare they are, and where they might be seen.

Birds of the West Indies, 2010, written and illustrated by Norman Arlott, published by Princeton University Press. Featuring color illustrations of sixteen birds on the front and two more on the back, this book is billed as an “illustrated checklist,” one of a series by Princeton University Press. It’s compact and crammed with information, and among its features are eighty color plates featuring more than 550 bird species, a short text that focuses on identifying the bird in the field, and distribution maps for each species.

Its compactness comes at a price—the typeface is tiny, as are many of the illustrations (try to differentiate the Cuban tody from its four cousins among the twelve illustrations on page 97, for example).

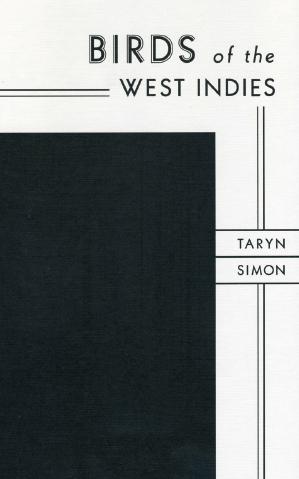

Birds of the West Indies, 2013, by Taryn Simon, published by Hatje Cantz, Germany. Two black-and-white Earl Poole illustrations, of a sharp-shinned hawk and a cloud swift that first appeared in the 1936 Bond edition, are featured at the beginning and end of the book.

Front cover of Herbert Raffaele’s 2003 Birds of the West Indies. Author’s collection

Front of the dust jacket for Taryn Simon’s 2013 Birds of the West Indies. Author’s collection

A leading conceptual-art photographer, Simon produced a large-format book with a front cover that pays homage to Bond’s 1936 dust jacket and reinforces the connection between him and Ian Fleming’s 007. A reviewer for Time magazine described the first part of the 440-page book as “a meticulous and mesmerizing meditation on materialism, masculinity, and geopolitical movements over the course of the last 50 years, via the vehicles, weapons, and women that have been featured in Bond films during the same period of time.”

In the second part of the book, according to Simon’s own description, she casts herself as “the ornithologist James Bond, identifying, photographing, and classifying all the birds that appear within the 24 films of the James Bond franchise.”

Birds of Mt. Desert Island

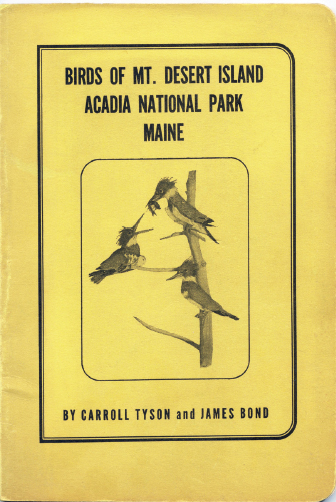

Bond wrote or cowrote field guides, scientific papers, and checklists for most of his adult life. The most enduring (and endearing) of the lot is an eighty-two-page booklet called Birds of Mt. Desert Island, Acadia National Park, Maine, written with his uncle Carroll Sargent Tyson Jr. The paperback, published by the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1941, is not your typical field guide. The authors not only watched the birds—they shot them.

On the very first page, for example, the entry on loons notes: “They dive with great dexterity when shot at, disappearing at the flash of the gun, thus rarely being hit.” In a description of the northern goshawk, the authors write: “We have several times disturbed a Goshawk at its feast of grouse and shot the marauder.” The common American crow, meanwhile, “is well known and widespread on Mt. Desert Island where it is jokingly referred to as ‘soup-meat’!”

Like Bond’s original Birds of the West Indies, the book is now a collector’s item and the progenitor of several subsequent editions, including a 2018 leather-bound reprint of the 1941 first edition. Ralph Long followed suit with his own privately printed version, beginning in the early 1980s. He dedicated the book in part to Bond, “who was the first to inspire my interest in birds and who compiled the early editions of Native Birds of Mt. Desert Island.”

Front cover of Carroll Tyson and James Bond’s 1941 book on Mt. Desert Island. Author’s collection

In the foreword of his forty-two-page paperback, Long wrote that Bond asked him to continue the tradition of “periodically reporting on the status of the breeding birds on Mt. Desert and nearby islands,” which “probably surpasses that of any area of comparable size and diversity of avifauna in Maine or any other New England state.”

Long’s booklet featured artwork by noted nature illustrator Ned Smith and—unlike the Bond and Tyson edition—made no mention of shooting goshawks or using crows for soup meat.

After Long died in the early 1990s, Rich MacDonald, of the Natural History Center in Bar Harbor, continued the tradition of writing about the island’s native birds. MacDonald says he’s developing the previous booklets into a full-size book of several hundred pages. Not surprisingly, he’s a fan of the real James Bond: “When I was about ten years old, I discovered a passion for everything bird,” he says. “Not long after that, I found a copy of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies in a yard sale. Given his name, I just had to learn more about this person.”

The only known photo of Bond and Fleming at Goldeneye in 1964. Photo by Mary Wickham Bond, Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department