CHAPTER

008

Twitchers & Spooks

If Ian Fleming’s choice of name for his secret agent was mere happenstance, it was also serendipitous. Ornithologists and birdwatchers have been some of the most successful members of the intelligence community in modern British and American history, and some of the most notorious too.

Although ornithology as a profession took root in the early 1800s, it wasn’t until the twentieth century that museums and universities routinely sent field scientists to far-flung corners of the globe. These researchers, especially ornithologists, became natural recruits for intelligence work during the two world wars, the Cold War, and other conflicts.

In a 2015 article for The Guardian, Helen Macdonald, author of H Is for Hawk, explained why birds and espionage dovetailed so nicely: “Birdwatcher is old intelligence slang for spy. . . . You have the same skills, the ability to identify, recognize, be unobtrusive, invisible, hide. You pay careful attention to your surroundings. You never feel part of the crowd.”

Ornithologists who work in foreign countries have an additional skill set that includes self-reliance, some fluency in other languages, and a familiarity with the local terrain, government, and customs. They’re outsiders but not strangers, so they don’t draw attention. They carry surveillance equipment such as spotting scopes and high-powered binoculars for their job. And they know their way around firearms.

Hundreds of birdwatchers/spies have likely existed over the past 120 years, including such notable Brits as Harry St. John Bridger “Sinjin” Philby (1885–1960), the now-notorious Richard Meinertzhagen, and British spymasters Maxwell Knight, Martin Furnival Jones, and Andrew Parker.

Sinjin Philby was a naturalist and brilliant double agent who helped bring the Middle East’s house of Ibn Saud under British influence during and after WWI, only to later help transfer the concession for Saudi Arabia’s vast oil holdings to the United States—a move that some believed bordered on treason.

Richard Meinertzhagen developed a fascination for birds as a youth—even poaching them as a student at Harrow in the early 1890s. He graduated in 1895, eighteen years before Jim Bond arrived on the campus. He gained fame as the inventor of the Haversack Ruse during WWI. A tireless self-promoter, he claimed he risked his life to plant a knapsack full of British military secrets along the front lines in Palestine to trick the enemy. The false documents led the Germans and their Palestinian allies to fortify their defenses at Gaza instead of the crucial freshwater wells 26 miles inland at Beersheba.

Ian Fleming was an acquaintance of Meinertzhagen’s in the 1930s and is said to have patterned some of 007 after the colorful intelligence officer. During WWII, Fleming was a commander in British naval intelligence and helped appropriate Meinertzhagen’s Haversack Ruse. The plan, known as Operation Mincemeat, involved planting disinformation on a corpse dumped by submarine along the Spanish coast to make the Nazis think the Allies were invading Greece instead of Sicily.

Decades after Meinertzhagen’s death, author Brian Garfield meticulously deconstructed the spy’s military exploits and ornithological career in The Meinertzhagen Mystery: The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud. Meinertzhagen, it turned out, not only exaggerated and misrepresented the impact of the Haversack Ruse and his role in it, but he was also was a real-life Baron Munchausen who used his diaries and memoirs to concoct wild stories of espionage out of half-truths. He is still suspected of committing a nasty wartime atrocity or two, as well as murdering his second wife, also an ornithologist, in 1928.

Martin Furnival Jones ran MI5, the United Kingdom’s internal security service, from 1965 until 1972. Andrew Parker took that position in 2013. Maxwell Knight, who specialized in supervising teams of undercover agents for several decades, is said to have been an inspiration for the character M in the 007 novels.

Knight went on to host a radio nature show for children, calling himself “Uncle Max.” Off the set, he reportedly kept a blue-fronted Amazon parrot in the kitchen and a Himalayan monkey in the garden. Knight also had the perfect pet bird for a secret agent—a common cuckoo named Goo. Cuckoos, like spies, are known to pretend to be what they are not and to lay their eggs in the nests of unsuspecting hosts—a bit of avian treachery.

Knight capitalized on his celebrity status to write more than a dozen books about nature. One such opus, Animals and Ourselves, featured a cover photo of Knight holding a young fox. The text that followed was leavened by the lively pen and ink drawings of David Cornwell, a young nature artist and intelligence officer. You may know him better by his nom de plume, John Le Carré.

“I actually worked alongside Maxwell Knight in MI5 for a year or two, so the literary partnership is not surprising,” Cornwell wrote in an email. “Our connection was of course known to our employers, but to no one else.”

A more recent American example of spymaster/birdwatcher is James Schlesinger, CIA director after Watergate and later secretary of defense under Presidents Nixon and Ford. Schlesinger was known for his hard-nosed managerial style and abrasive personality. In a 2011 article for the New York Times, the author Richard Conniff wrote that CIA historian Nicholas Dujmovic told him, “the only nice thing I’ve ever heard about Schlesinger is that he was a birdwatcher.” Neither Schlesinger, Jones, Parker, nor Knight, however, was known to use ornithology as a cover for spying activities. They were too high up in the pecking order to find it useful. Birdwatching was more of a diversion that helped take their mind off the grind of running a high-pressure intelligence outfit.

Then there was Fleming himself, an avid birder who learned the espionage trade as deputy to Admiral John Godfrey, director of British Naval Intelligence during WWII.

Fleming’s overseas travels included trips to the United States (to coordinate the two nations’ intelligence operations), to Canada (where he reportedly attended Camp X, a secret training ground for OSS agents), and to Jamaica (to attend a naval conference and, according to Matthew Parker’s Goldeneye, to investigate rumors of a secret Nazi submarine base in the Bahamas).

In a 2008 Times of London article, author Ben Macintyre described Fleming’s wartime communications with US general William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who was then forming the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. One seventy-two-page memo from Fleming in 1941 advised that the ideal secret agent “must have trained powers of observation, analysis and evaluation; absolute discretion, sobriety, devotion to duty; language and wide experience, and be aged about 40 to 50.”

The OSS was created as a fourth arm of the US military, providing intelligence, propaganda, and commando operations. Donovan recruited Americans who traveled overseas, studied world affairs, and spoke foreign languages. That typically meant going after the so-called “best and the brightest” at universities, businesses, and law firms on the East Coast. The list of notable people involved with the OSS includes future Middle East peace negotiator and Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche, future cookbook author Julia Child, future CIA director William Casey, actor Sterling Hayden, future CIA director Allen Dulles, and future Supreme Court justice Arthur Goldberg.

OSS operatives also included three of Bond’s contemporaries at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and at least four of his fellow ornithologists at major natural-history museums. All of them knew Bond and had made ornithological expeditions to foreign countries. They also corresponded with Bond, belonged to the same professional groups, and in some cases worked alongside one another.

They included Brooke Dolan II and Frederick E. Crockett of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Herbert Girton “Bert” Deignan of the Smithsonian Institution, S. Dillon Ripley II of Yale’s Peabody Museum (he had also worked at the ANSP), James Paul “Jim” Chapin of New York’s American Museum of Natural History, and W. Rudyerd “Rud” Boulton of the Field Natural History Museum in Chicago. Yet another ornithologist, Emmet Reid Blake of the Field Museum, worked for US Army counterintelligence and had the most incredible espionage career of them all.

(As Gordon Corera wrote in Operation Columba, the OSS also employed carrier pigeons, “dropping them behind enemy lines in Europe and with agents in Asia.” But that’s a spy of a different feather.)

Although much of what the OSS did is still under wraps, you can get a glimpse of its activities—and the paperwork its employees had to contend with—by visiting the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Located in an enormous glass-and-steel building near the sprawling University of Maryland campus, the 1.8-million-square-foot building is home to 21,000 boxes—7,000 cubic feet—of OSS records, including personnel files. That material ranges from expense-account paperwork and human-resources-department minutiae to an occasional nugget. The greater the achievement, the thicker the files and the more glowing the prose.

America’s ornithologist spies were largely anonymous, performing highly stressful jobs in postings in such places as Africa and Asia. Spycraft was often a bad fit. According to a declassified history of the agency, War Report: Office of Strategic Services; Operations in the Field, communications challenges severely hampered agent operations. “SI[Secret Intelligence]/Africa first pursued the policy of selecting agents from persons who had already resided in the target areas,” the report reads. “The policy was eventually abandoned when experience showed that such individuals were scarce and often not those most suited for intelligence work.”

James Paul Chapin

The anonymous authors of that report may well have had Jim Chapin in mind when they wrote their appraisal. Future spy Chapin (1889–1964), Bond’s counterpart at the American Museum of Natural History, wrote Birds of the Belgian Congo in four parts over more than two decades, after gaining widespread fame for his discovery of a new species of African peacock in, of all places, the storeroom of a museum in Belgium.

In 1919, while studying at Columbia University, the twenty-year-old Chapin joined what turned out to be a six-year expedition to collect fauna and flora in the Congo basin. About two years into the trip, he saw an unusual feather in the headgear of an African tribal leader. Chapin couldn’t identify the feather, except to determine it was a secondary flight feather, but he saved it for later reference. More than two decades later, while examining study skins at the Congo Museum outside Brussels, Chapin saw two discarded specimens of an unidentified peacock-like bird that were reportedly collected in the Congo. Chapin realized that the flight feather he’d collected twenty-three years earlier was from the same species. The following year Chapin led an expedition to the Congo to find the mystery bird. He did and called it the Congo peacock, Afropavo congensi.

James P. Chapin, shown here in Leopoldville, Congo, in 1942, worked for the OSS there and was a Bond contemporary. Courtesy of TL2 project, Lukuru Foundation

Bond and Chapin were well acquainted. In her memoir To James Bond with Love, Mary writes of how Bond rushed to the American Museum of Natural History after an expedition in which he had collected several rare Saint Lucia finches, which resemble one of Darwin’s famous Galápagos finches:

“On his return to New York he again stopped in at the American Museum. James Chapin, head of the African Department, was standing on a ladder working on his collection and asked Jim politely, ‘And how was your trip?’ Jim couldn’t resist sounding a little triumphant when he replied, ‘I collected a genus you haven’t got in the American Museum,’ and told his story. Chapin rushed off with the news to Frank Chapman, head of the bird department, who sat down then and there and wrote to Witmer Stone, curator of birds at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, asking for one of the specimens.”

In 1942, Chapin joined the OSS and was deployed as a special assistant to the American Consul in Leopoldville (now known as Kinshasa), the capital of the Belgian Congo (Democratic Republic of Congo). He was even assigned a code name, CRISP. Chapin was given the job for two reasons—because he had spent all those years in the Congo as an ornithologist, accumulating invaluable local knowledge, and because the Congo held by far the world’s largest supply of high-grade uranium.

Three years earlier, Albert Einstein had written to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might develop an atomic bomb and urging him to protect the uranium from the Congo’s Shinkolobwe mine. The OSS wanted to get the uranium out of the mines at Shinkolobwe before the Nazis could get their hands on it. As it turned out, the mine’s uranium was crucial to the Americans’ Manhattan Project.

Alas, Chapin’s stint undercover in the Congo did not go well. His assignment included sharing intelligence with OSS operations in neighboring countries, investigating activities by enemy agents, and expanding intelligence operations in Africa. He was soon overwhelmed by the job, which also included the painstaking chore of translating all his correspondence into secret code, which took hours at a time.

Much of Chapin’s thin OSS personnel file involves medical matters, although one expense report for his Belgian Congo work included “two suits of ‘safari’ clothes,” as well as a gun permit for a 12-gauge shotgun. By April 1943, it had become clear in Washington that Chapin couldn’t handle the pressure, and he was sent stateside, where he spent several months at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore before being discharged.

Jim Chapin’s ornithological expertise came in handy on his way to Africa for the OSS—forcing sooty terns to nest away from an airstrip. Author’s collection

In September 1943, a week after being discharged, he returned to the American Museum of Natural History. After the war, Chapin and his wife, Ruth Trimble Chapin, lived in the eastern Congo from 1953 to 1958, where they studied birds. He died at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan on April 7, 1964, age seventy-four. At that time, he was the museum’s curator emeritus, still engaged in bird research.

Waging War on the Wideawakes

On Jim Chapin’s way to the Congo, his birding acumen unexpectedly proved pivotal. As Susan Williams recounted in Spies in the Congo: The Race for the Ore That Built the Atomic Bomb, his plane had to make a refueling stop at a US Army Air Forces landing strip on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic. When the base commander learned that an ornithologist was visiting, he asked Chapin to solve a problem that was threatening all outbound flights: a colony of sooty terns.

The birds, known locally as wideawakes, had established a major nesting ground just beyond the end of the newly constructed runway. When a plane headed down the runway, the rumble of the engines spooked the birds and sent them into the flight path. As The Army Air Forces in World War II (vol. 7) described the situation, heavier planes couldn’t gain altitude fast enough to avoid the birds and had to fly right through them, “running the risk of a broken windshield, a dented leading edge, or a bird wedged in engine or air scoop.” The problem was so bad that the airstrip was known as Wideawake Airfield.

Ground crews had tried everything from smoke candles and dynamite to feral cats, with no success. Enter Chapin, who advised that if the wideawakes’ eggs were destroyed, the birds would nest elsewhere. Some 40,000 smashed eggs later, the terns relocated, and pilots and crews rested easier for a little while.

W. Rudyerd Boulton

Rud Boulton (1901–1983), a museum ornithologist in New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago, was a specialist in the birds of Angola. He participated in several expeditions to Africa and the Americas but published little, aside from Traveling with the Birds, a delightful and plainspoken 1933 children’s book about bird migration.

With the onset of WWII, Boulton left his job at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and joined the OSS. He became head of the Secret Intelligence desk for Africa, including Jim Chapin’s sector, and was connected to the top-secret import of Congolese uranium for the Manhattan Project atomic bomb development. Another prime mission was to keep tabs on German operatives in West Africa and prevent the Nazis from smuggling that uranium out of the Congo.

Boulton’s OSS files include a memo instructing him (code name: NYANZA) to travel to Africa to look into counterintelligence operations. “You will complete the mission with all possible dispatch and return to Washington where you will make a complete and detailed report to the acting chief of X-2 and the acting chief of SI.” (“X-2” was the OSS abbreviation for counterintelligence, and “SI” was special intelligence.)

Among his assignments: go to Tangier to discuss the German-Spanish intelligence situation. The OSS had learned that the Germans weren’t liked and that the intelligence they gathered from Spain was the result of bribes. The OSS’s plan was simple: “It is suggested we get a Spanish American of attractive personality and outbid the Germans.” (The OSS was known for outbribing other intelligence agencies, friend or foe.)

W. Rudyerd Boulton of Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History worked for the OSS as head of the Secret Intelligence desk for Africa. © The Field Museum

After the war, Boulton apparently was not as eager to get back to museum work as Chapin. In A Look over My Shoulder, Richard Helms wrote about the transition from the OSS to the CIA: “The morning the termination order was announced at General Donovan’s staff meeting, Rudyerd Boulton, a soft-spoken internationally known ornithologist specializing in Africa, shot up from his chair. Thrusting his arms toward heaven, he shouted: ‘Jesus H. Christ. I suppose this means that it’s back to those goddamn birds,’ and stumbled from the room. In those days, African specialists were hard to come by, and the professor was to remain with the CIA until his retirement.”

As Susan Williams recounted in Spies in the Congo, when Boulton learned that his former OSS Africa operative Jim Chapin was scheduled to talk to the Explorers Club in Manhattan about his experiences on Ascension Island, he wrote to Chapin about keeping his wartime stint in the Congo a secret: “No mention of the OSS or of me [should] be made during the course of it.”

Two years later, Chapin named a subspecies of Cameroon scrub warbler after his OSS boss—Bradypterus lopezi boultoni. After retiring in the 1960s, Boulton returned to Africa with plans to conduct bird research, although the parabolic microphones he brought with him seemed better suited for eavesdropping.

The OSS efforts in Africa were successful. As Williams noted in Spies in the Congo: “None of the Congolese ore, so far as is known, was sent from the Congo to Nazi Germany between 1943 and 1945, whether by smuggling or any other means. And without sufficient uranium ore of that uniquely rich quality, the German atomic project could not succeed.”

S. Dillon Ripley II

Dillon Ripley (1913–2001) attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire thirteen years after Bond. Among his achievements there, Ripley founded the Offal-Eating Club, whose members retrieved, cooked, and dined on roadkill rabbits and pheasants. Ripley later studied ornithology at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. In 1937, the 6-foot-3 Ripley went on an eighteen-month expedition for the Academy of Natural Sciences, recruited by Bond’s longtime colleague Rodolphe De Schauensee. Ripley traveled on a 60-foot schooner from Philadelphia through the Panama Canal and the South Pacific to Dutch New Guinea to collect specimens of exotic birds. (Also on the trip was ANSP contemporary Frederick E. Crockett, who also joined the OSS—but more on him later.) Ripley wrote about the expedition in his 1942 book Trail of the Money Bird, billed on the dust jacket as “30,000 miles of adventure with a naturalist.” In his foreword, Ripley thanked several people he met in New Guinea, noting that “since I have known them much has happened. Many of them are in peril for their lives.”

S. Dillon Ripley II (second from right) worked for the OSS in Southeast Asia. His duties included training Indonesian spies. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, image #SIA2010-0866

In 1984, an interviewer for the New York Times asked Ripley if he used the disguise of birdwatcher to spy on the Japanese. His reply: “Curiously enough, the British, and I suppose the Indians, Pakistanis, Ceylonese and so on, thought that it was such a marvelous part of an old-fashioned cover. Their theory was that most obviously we were spies. It never seemed to be realistic because I never could discover what someone out in the bushes could discover in the way of secrets.”

Those were the words of a spy dissembling. Ripley was a fearless spy, stationed in India and Pakistan. A superior’s handwritten note in Ripley’s OSS file reads: “Dr. Ripley’s professional planning, knowledge, consistency in foresight and sound judgment in Intelligence contributed in a great measure to the successful planning and completion of clandestine military operations against the enemy. His record of achievement, willingness to serve at advance bases and behind enemy lines in close contact with the enemy without any regard for his own safety is an inspiration to others.”

Here’s how a 1950 profile of Ripley in the New Yorker described his years as spymaster/ornithologist, all in one lollapalooza of a sentence: “Ripley, who was attached, as a civilian, to a military unit of the South East Asia Command, and whose duties included training, equipping, briefing, and sending into Java and Sumatra four Indonesian spies, all of whom were eventually killed, as well as dispatching behind-the-lines undercover men to assist guerrillas in South Burma, Malaysia, and Thailand, went on to report the sighting of such creatures as purple sunbirds, seven-sisters babblers, white-breasted kingfishers, scops owls, paradise fly-catchers, and a variety of storks and herons.”

During a wartime OSS trip to the island nation of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Ripley met Mary Livingston, his future wife, who also worked for the OSS—as did her roommate, Julia Child.

After the war, Ripley returned to ornithology and became director of the Peabody Museum at Yale. He later served as head of the Smithsonian until 1984, a key figure in the institution’s golden age of expansion and acquisitions. Ripley remained friends with Bond and went on an expedition to the West Indies with him in 1960.

At least one bird species is named for Ripley—the Himalayan shrike-babbler (Pteruthius ripleyi)—as well as several subspecies, including a bay owl (Phodilus badius ripleyi) and a Thailand pitta (Pitta guajana ripleyi).

Herbert Girton Deignan

Herb Deignan (1906–1968) was an OSS colleague of Ripley’s in Ceylon and a 1928 Princeton grad who taught English in Thailand for four years and collected birds there in his spare time before joining the Smithsonian Institution. In 1937, several years before Deignan joined the OSS, Bond’s colleague, Rodolphe De Schauensee, named a bird for Deignan in honor of his ornithological work in Thailand.

When WWII arrived, Deignan’s familiarity with Asia and his ability to speak Thai made him a perfect OSS recruit. By then Japan occupied Thailand, and Deignan was assigned to Ceylon, where he worked with a group of Thais and Americans involved in the Free Thai movement. For his wartime efforts, Deignan received a medal of merit and the Order of the White Elephant (fifth class) by the King of Thailand (the first four classes of the order were reserved for royalty).

Deignan was the author of The Birds of Northern Thailand, published in 1945, the final year of the war. He sent back 143 bird skins, 6 bird skeletons, and 236 shells and barnacles, plus mammal, reptile, insect, snail, and worm specimens, to the Smithsonian that year. He was an expert in several families of Asian birds, including the Asiatic bulbuls and the babbling thrushes.

Herbert Deignan worked for the OSS with Dillon Ripley in Southeast Asia. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, image #SIA2009-1775

When asked on one OSS form called “Individual’s personal desire as to future assignment,” Deignan wrote: “To return to the Smithsonian Institution in January,” which he did.

In 1952, he returned to Thailand as a Guggenheim fellow. Like his OSS colleague Jim Chapin, his happiest times in the years after the war were working as an ornithologist in museums. As his obituary in the October 1989 The Auk stated: “Museums and research were to him havens in a troubled world, and as he saw little in the way of easing the troubles, he preferred to absent himself from as much of them as he could.”

Deignan’s name is best remembered in Sri Lanka for the threatened species Lankascincus deignani, a.k.a. Deignan’s tree skink, found in the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka 600–2,300 meters (1,968–7,544 ft.) above sea level. In 1951, Deignan named a subspecies of cocoa thrush after Jim Bond, Turdus fumigatus bondi.

Brooke Dolan II

Bond’s ANSP contemporary Brooke Dolan (1908–1945) was an explorer and OSS member who became famous for his wartime exploits. Educated at St. Paul’s School (he arrived in 1921, eight years after Bond left), Princeton, and Harvard, the independently wealthy Dolan spoke Tibetan and Chinese and was well versed in Buddhism.

Dolan first gained fame in 1931, when he led an expedition to northeastern Tibet and western China that brought the first specimens of the giant panda to the United States. During a second expedition, in 1934–1936, he collected 3,000 birds and 140 mammals from Tibet and western China and covered approximately 200,000 square miles of territories often ruled by competing warlords. The expedition members encountered infectious diseases, blizzards, quicksand, food shortages, and marauding nomads. These credentials made him perfect for the OSS.

Brooke Dolan II visited Tibet three times, including an expedition for the OSS in 1942–43. ANSP Archives Collection 64 (restricted), Dolan, Brooke, II, 1909–1945, Papers, 1931–1946

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent Dolan and Captain Ilya Tolstoy (grandson of the novelist) on a reconnaissance mission to Tibet and China to look into the feasibility of a new supply route over the Himalayas into Tibet and China to investigate possible airfield sites, and to gauge attitudes toward the war within the various regions they explored.

Here’s how one of Dolan’s OSS superiors, Colonel M. Preston Goodfellow, described the seven-month trek: “Throughout the accomplishment of the mission, Captain Dolan met and overcame extreme difficulties of travel, weather, terrain, excessively high altitudes and danger from native populations whose attitude toward himself and his mission was not previously known. . . . [He was able to] proceed to and through places never seen before by white men.”

Along the way, Dolan and Tolstoy met with the Dalai Lama, only seven years old at the time, to give him gifts and a message from President Roosevelt.

Given the conditions, Dolan had by far the best requisition orders / expense-account items in his OSS personnel files. One equipment request included hand grenades, irritant gas, helmets, and two .45-caliber automatic Colt pistols with magazine clips and holsters.

After returning home, Dolan was transferred to the US Army Air Forces. He returned to China once more to gather intelligence for the headquarters of the 20th Bomber Command. He died there in August 1945 at age thirty-seven. The war had already ended.

Dolan’s eared pheasant (Crossoptilon crossoptilon dolani) was named for him.

Frederick Eugene Crockett

Another celebrated contemporary at the Academy of Natural Sciences who joined the OSS was Harvard-educated Freddie Crockett (1907–1978), a dog handler and radio operator on Admiral Richard Byrd’s first South Pole expedition (salary: $1 per annum).

From 1934 to 1936, Crockett prospected for gold in the southern United States and Mexico before joining the academy. Crockett’s claim to fame there: he and his wife, anthropologist Charis Denison Crockett, led an expedition to the Galápagos, Polynesia, the Solomons, New Britain, and New Guinea that included fellow future OSS member Dillon Ripley.

During WWII, Crockett served in the US Navy and Army Air Corps in Greenland and the Arctic, focusing on intelligence work and sea rescues before becoming an Arctic-related military instructor stateside.

In 1945, Crockett was recruited by the OSS and sent to Jakarta on a mission code-named ICEBERG—perhaps a nod to his days in the Arctic and Antarctic. According to William J. Rust in the March 2016 article “Operation ICEBERG” for Studies in Intelligence, Crockett’s mission had two goals: “The first was immediate and overt: helping rescue US POWs from Japanese camps. This humanitarian assignment provided cover for a second, longer-term objective: establishing a field station for espionage in what would become the nation of Indonesia.”

Explorer Frederick Crockett sailed to New Guinea aboard Chiva in 1937 with Dillon Ripley. As part the OSS, he later rescued American prisoners of war in Indonesia. Author’s collection

In terms of his qualifications, the assigning officer wrote that Crockett had spent a lot of time in the area, “speaks the language, and knows and understands the people. He has extensive small-boat training as well as cryptography, radio communications and procedure.”

Alas, the operation’s results were mixed, with Crockett reporting that his efforts to evacuate American prisoners of war and civilian internees was “directly contrary to the policy of the British and Dutch.” Similarly, Crockett reported that his intelligence-gathering efforts were constantly undermined by his Dutch and British counterparts, who “were worried that US observers would report unfavorably, even though accurately, on their subtle endeavours to restore a ‘status quo ante bellum.’”

According to that official history of the CIA, “[Crockett’s] postwar career included an unsuccessful bid for political office in California and a return to the CIA in the early 1950s. He died in 1978, having spent the last twenty-four years of his life as a commercial real estate broker.”

Admiral Byrd named Mt. Crockett, a prominent peak in Antarctica’s Queen Maud Mountains, for him. In 1939, Rodolphe De Schauensee and Ernst Mayr also named a yellow-gaped honeyeater after him—Meliphaga flavirictus crockettorum.

Emmet Reid Blake

For pure 007-style derring-do, it’s tough to top Bob Blake (1908–1997), Bond’s other counterpart at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. Blake grew up precocious in South Carolina, with a fascination for birds and a penchant (like Maxwell Knight) for carrying reptiles in his pockets, which earned him the nickname Snakey.

He entered the Presbyterian College of South Carolina as a fifteen-year-old and soon turned a vacant dormitory into a natural-history museum for small mammals and birds that Blake and a pal had shot and skinned. Although he liked studying ornithology, he wrote to his mother that he wanted to be an explorer: “I love travel, excitement, outdoor life and the beauties of nature.”

After graduating, Blake roller-skated 900 miles to become a part-time grad student at the University of Pittsburgh. He took a break from his studies to join a yearlong National Geographic Society trek up the Amazon River in Brazil, where he served as a bird skinner, cook, and dishwasher.

When the rest of the expedition went home, Blake remained. Working eighteen-hour days, he collected 803 birds, 86 reptiles, and 37 mammals. One of the lizards was new to science and eventually named Anadia blakei.

When he returned stateside, the Great Depression was in full swing, and he paid his way through graduate school by working jobs that included private detective, gas-station attendant, and carnival boxer.

After getting his master’s in zoology, Blake joined the Field Museum in 1935 and became assistant curator of birds. Blake’s interest in birds got him into US Army counterintelligence in WWII. The army had originally assigned him to be a stretcher bearer, but when an intelligence officer learned that young Blake had made several field trips to South America as an ornithologist and spoke Spanish and Portuguese, he suggested sending Blake to keep an eye on Nazi sympathizers in South America.

Instead, Blake was sent to North Africa, where he worked his way north into Europe, ferreting out German spies who had infiltrated American forces. According to a May 1946 article in the Index-Journal of Greenwood, South Carolina, he also helped track down a truckload of Gestapo-held gold bullion in Bavaria and received a Bronze Star for “heroism and meritorious service that included apprehending four SS men in the town of Wuerzburg while the town was under enemy shellfire and heavy street fighting was in progress.” The article noted that “valuable information of a counterintelligence nature was obtained in Wuerzburg during his operations.”

After the war, Blake returned to the Field Museum and in 1953 published The Birds of Mexico, the Mexican equivalent of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies. He claimed that despite his many expeditions, he never went on an adventure. “A professional doesn’t look for adventures. To have an adventure is to admit stupidity and incompetence. We prefer to call close calls ‘acts of God,’” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1980.

As Blake also told the Chicago Tribune: “There’s not much similarity between hunting birds and hunting spies, except that each requires careful planning.”

Emmet Reid Blake of the Field Museum worked for US Army counterintelligence in North Africa and Europe during WWII. © The Field Museum

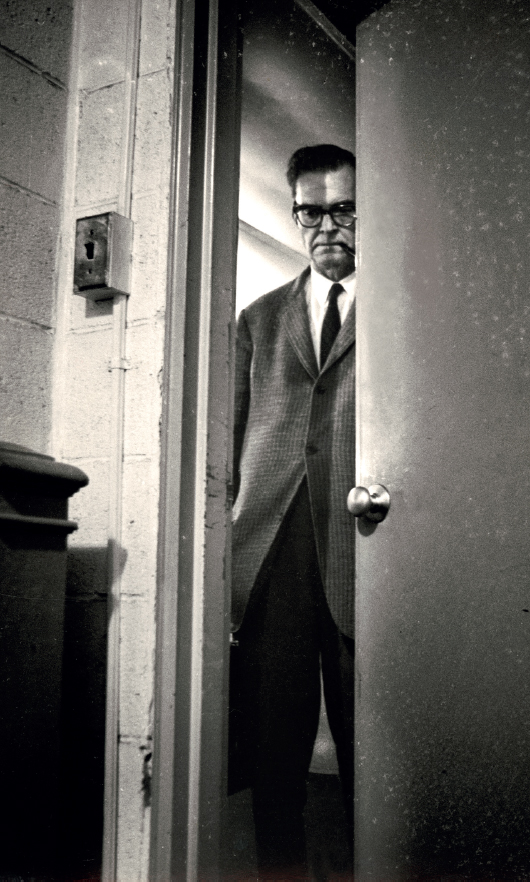

Jim Bond leaving his corner office at the ANSP. Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department