CHAPTER

009

Was Jim Bond a Spy?

Could the real James Bond also have been a spy? Probably not, but there are enough intriguing connections that it’s fun to speculate.

In his fictional biography of James Bond (James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007), author John Pearson certainly flirted with the idea. Pearson’s story has Fleming discovering the existence of an actual secret agent named James Bond, whom he met in the lobby of a Caribbean hotel: “Even in those days, James was engaged in some sort of undercover work.”

The fictional biography also posited that Fleming’s real purpose in writing the 007 stories was to make his fictional Bond such a comic-book superhero that the Russians would fail to take the real Bond seriously, thereby allowing him to continue his secret work. Other theorists—notably William Kelly in his blog James Bond Authenticus—have explored that possibility, combing through Bond’s career and Mary’s memoirs for clues pointing to a life of espionage. Could it have been possible?

A case could be made from the circumstantial evidence. Bond attended two schools that educated future spies. He went to the West Indies during an era of Nazi intrigue. During WWII, at least six of his contemporaries affiliated with natural-history museums worked for OSS, and a seventh worked for US Army Counterintelligence.

At several points in Jim Bond’s four decades in Cuba, Haiti, and other hotspots in the Caribbean, he would have been a useful source of information for US intelligence agencies.

As Mary Bond wrote in To James Bond with Love, her husband was in the Dominican Republic when Rafael Trujillo took power in the early 1930s—and even had the dictator sign his collecting permit. And he was in Cuba in early 1961, shortly before the infamous Bay of Pigs Invasion, in which the United States bankrolled dozens of Cuban expatriates in their efforts to overthrow the iron-fisted Castro regime.

In other instances, Bond certainly was in peculiar places at peculiar times. Ian Fleming himself wrote in Goldfinger that something that happened once was happenstance. Twice was coincidence. And three times was enemy action.

The SS America, which had its name and American flags emblazoned on its hull in hopes German U-boats wouldn’t torpedo it, was painted in a camouflage pattern when it became the USS West Point. Public domain

First, his schooling—in theory the perfect academic arc for a future spy. At age twelve, Jim Bond attended St. Paul’s School for two school years. The boarding school also educated future spies S. Dillon Ripley and Brooke Dolan II.

The next stop in Jim Bond’s academic career was Harrow School in North London. Harrow was also the alma mater of the infamous Richard Meinertzhagen, the notorious British spy and ornithologist. Bond went to the same university as Meinertzhagen, Cambridge’s Trinity College—home to Kim Philby and the most notorious spy ring of the twentieth century.

After college and a brief detour as a banker, Bond worked as an ornithologist for the Academy of Natural Sciences, where his contemporaries included Ripley, Dolan, and the other five American operatives described in the previous chapter.

Those connections could lead one to suspect that Bond was somehow involved with the OSS as well, but he would have been in the OSS personnel files if he had worked directly for them, and the agency rarely recruited agents who had gone to college overseas. Besides, it’s far more productive to review what is fact, not speculation.

Bond was by all accounts an excellent observer and solid marksman. He could speak limited French and Spanish and by WWII had excellent local knowledge and government contacts in many islands in the West Indies, including Cuba, the Bahamas, Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. His ornithological research in any of these countries would have provided him with perfect credentials to return undercover.

One such story of intrigue involved a trip to Haiti in the late spring of 1941. Europe was already at war, and the United States was seven months away from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, Haiti was neutral as well. Like the United States, it declared war on Japan the day after their sneak attack had killed more than 2,400 Americans and wounded another 1,178. Haiti declared war on Germany and Italy shortly afterward.

Mary recounted the incident in her 1980 memoir, To James Bond with Love:

If Ian Fleming had lived longer, it’s a safe guess that he and Jim (Bond) would have met again. Fiction writers are scavengers when seeking material for their fabrications, and Fleming might have easily extracted from Jim his enigmatic experience in World War II in Haiti. He arrived in Port-au-Prince in May 1941 for the sole purpose of studying birds on Morne La Selle, a plateau over 6,000 feet high. He put up at the little Hotel de Reix at Kenscoff, a small settlement at about 4,000 feet and tried to obtain two porters to carry his camping material. No one would go. A German, he was told by the inhabitants, had built an airstrip high on the ridge and would not allow anyone to go up there. Jim asked where the German lived, and the natives pointed to the summit of nearby Morne Tranchant which is covered by low scrubby woods. Jim was doubtful of this, for he was used to near-enough gestures from the islanders when asked the location of some rare bird, but decided to go up and see for himself.

Bond’s name was the first one on the passenger list for the SS America’s cruise to the West Indies that sailed from New York in May 1941. National Archives, public domain

He climbed to the top of the mountain and found on the edge of a small clearing a very neat cottage well hidden in the foliage. The German who came out was very pleasant, spoke excellent English, and although he did not say, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” to Jim’s astonishment he knew who he was and told him to go ahead wherever he pleased on the La Selle ridge. Jim was so absorbed in his own objectives he forgot all about the alleged airstrip and went on his way without even asking about it.

When leaving Haiti for home, he was forced, owing to the war, to travel on a freighter from St. Marc [in Haiti] to New York. Back in Philadelphia he told his friend Brandon Barringer about the encounter with the German, and Brandon took it up with the authorities in Washington. Jim was promptly visited at the Academy of Natural Sciences by Army, and then Navy, Intelligence officers. Fleming would have been intrigued with the final twist to the story. The Intelligence people asked a lot of foolish questions and seemed far more suspicious about Jim’s reasons for climbing Morne La Selle than about the German’s activities.

This trip had a couple of other odd aspects. Perhaps it was just a coincidence, but the trip was not listed in the Academy of Natural Sciences’ annual proceedings (only five were listed that year). It was the first year for which no Bond trip had been included. But that’s only the half of it.

For starters, on May 10, 1941, Bond left New York City on the 723-foot-long SS America, bound for Haiti. It made the round trip between New York and the Caribbean every two weeks This United States Lines ship, which had a cruising speed of more than 23 knots, was billed as “the largest, fastest and most luxurious ship ever built in the United States”—a far cry from the cargo ships and mail boats that Bond typically used. In addition, the ship had been secretly designed so that it could be converted into a troop carrier if war with Germany broke out. The SS America was launched on August 31, 1939, the day before Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Although the ship had been intended for luxury transatlantic crossings, her permanent route was soon switched to New York and the Caribbean, where she would travel in neutral waters, farther away from the war in Europe and Hitler’s U-boats.

The SS America dropped off Bond at Port-Au-Prince on May 16. The trip would be the luxury liner’s penultimate cruise for eight years. On May 21, in the South Atlantic, a German U-boat stopped the SS Robin Moor, an American cargo ship that proclaimed its wartime neutrality with a large “USA” and American flag painted on its hull. After giving its thirty-eight merchant seamen and eight passengers a few minutes to board four lifeboats, the U-boat torpedoed and shelled the Robin Moor until it sank.

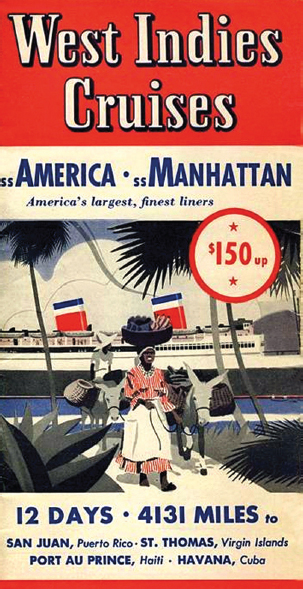

A 1941 Brochure for the SS America’s Caribbean cruises. Public domain

Soon after, on June 1, the US Navy requested that the SS America be converted into a fully operational transport ship. Over the next two weeks, the 1,202-passenger liner was refitted to carry some 5,400 troops at a time.

On June 20, in a radio address, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said the sinking of the Robin Moor was perpetrated by a Nazi U-boat and called the actions “outrageous and indefensible.”

That same day, as Peter Duffy recounts in his book Double Agent, German expatriates Erwin Wilhelm Siegler and Franz Joseph Stigler, a butcher and a baker who worked in SS America’s kitchen, were secretly arrested on charges of attempting to leave the country without notifying their draft board.

On June 28, 250 agents arrested more German spies. In all, Siegler and Stigler and thirty-one others were charged as part of a massive spy ring. Siegler, the ship’s butcher, was one of the Duquesne Spy Ring’s organizers and contacts. He obtained information about the movement of ships and military defense preparations at the Panama Canal. He was sentenced to ten years on espionage charges.

Stigler, the ship’s baker and confectioner, had sought to recruit amateur radio operators in the United States to communicate with German radio stations. He had also reported defense preparations in the Canal Zone and had advised other German agents. Stigler was sentenced to serve sixteen years.

A third enemy agent who had worked aboard the SS America, Hartwig Richard Kleiss, had passed along information to the Germans, including blueprints of the ship that showed the locations of gun emplacements and how the guns would be brought into position for firing. Kleiss also obtained details on the construction and performance of new speed boats being developed by the US Navy, which he tried to pass along to Germany. He pleaded guilty to espionage and received an eight-year sentence.

The Duquesne Spy Ring included three SS America crewmen—Hartwig Kleiss, Erwin Wilhelm Siegler, and Franz Joseph Stigler. Library of Congress, public domain

Of the thirty-three members of the German spy ring, sixteen pleaded guilty and the others stood trial and were convicted. The Duquesne Spy Ring was considered the largest espionage case that ended in convictions in American history.

If Bond did work for American intelligence operations, however unlikely, the US government would have kept a file on him. Under the Freedom of Information Act, a request was made in late 2016 for all documents and files pertaining to ornithologist James Bond.

The CIA’s information and policy coordinator, Michael Lavergne, offered this hazy response: “After conducting a search reasonably calculated to uncover all relevant documents, we did not locate any responsive records that would reveal an openly acknowledged CIA affiliation with the subject.

“To the extent that your request also seeks records that would reveal a classified association between the CIA and the subject, if any exist, we can neither confirm or deny having such records, pursuant to Section 3.6(a) of Executive Order 13526, as amended. If a classified association between the subject and this organization were to exist, records revealing such a relationship would be properly classified and require continued safeguards against unauthorized disclosure.”

Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department