CHAPTER

010

Bond’s Legacy

The real James Bond probably would have cringed at this book. As his ANSP colleague Robert McCracken Peck commented, “He went under the radar as much as he could and resented any kind of publicity.” However, he didn’t fly under the radar nearly as much as he would have hoped—thanks in part to his wife and main promoter, Mary.

No biography of Jim Bond would be complete without an assessment of his legacy. Separating Bond from his unwanted 007 connection is difficult, since it has—albeit inadvertently—raised awareness of Caribbean birds and birding for more than half a century, To evaluate Bond’s own achievements, one must examine three aspects of his career: his books (notably Birds of the West Indies in all its incarnations), his scientific research (including “Bond’s Line”), and his impact on ornithology, birding, and the Caribbean.

George Armistead of Philadelphia, who has led dozens of birding tours, including one called “The West Indies: Birding James Bond’s Islands,” described the impact of Birds of the West Indies. “[It] brought to life birds that before then had only been dreamt of, and the magic of the todies, the lizard-cuckoos, the bullfinches, and some very fancy hummingbirds spilled onto the pages. That book was, for the better part of seven decades, the bible for birders visiting the region.”

Armistead says, “I think his book was a landmark achievement that made the region as a whole seem suddenly accessible, and surely inspired a lot of travel and was the stepping stone to further research.”

When I visited Orlando Garrido in Havana, the legendary Cuban ornithologist peppered his conversation with references to two pioneering ornithologists he most admired, Cuba’s Juan Gundlach and James Bond.

Garrido called Bond’s Birds of the West Indies “the singular tome for bird studies” and said he thought Bond’s “Checklist of Birds of the West Indies” and its many supplements were his biggest contributions to ornithology.

Jamaican environmental researcher Catherine Levy, who wrote about the history of Caribbean ornithology for the journal Ornitología Neotropical, says that Bond “definitely spurred interest in the birds of the Caribbean, first from a visitor’s point of view in providing a field guide for the first time, and providing information to locals.”

Because Birds of the West Indies was published in so many editions over so many decades, several generations of birders have felt its impact. Consider this recollection from Frederic Briand, head of the Mediterranean Science Commission, for the National Geographic’s blog in 2012. In the late 1970s, as Briand was conducting research at Discovery Bay Marine Laboratory in Jamaica, he decided to go inland and explore the Blue Mountains on a day when the seas were too rough for fieldwork. He ended up in a remote forest field station, looking through binoculars at a huge variety of local birds that ranged from hummingbirds to woodpeckers to parrots.

When Briand asked a forest ranger for help in identifying the birds, the ranger handed him a large field guide—“the very best,” according to the ranger.

“That copy had seen better days for sure; it was worn out, some pages were missing,” Briand wrote. “But it contained hundreds of drawings and annotations depicting the diverse bird fauna of the Caribbean islands. A pioneering study. The name: Birds of the West Indies. The first year of publication: 1936. There were many editions to follow. The author: a certain James Bond, a leading American ornithologist, working at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.”

Bond’s legacy also includes the Smithsonian Institution’s James Bond Fund, earmarked for Caribbean ornithological research. He donated a sizable part of his estate to the Smithsonian and not the Academy of Natural Sciences, as one might have expected, for reasons that are not clear. It might have been because of some perceived slight by the academy, or because of his friendship with Smithsonian directors Dillon Ripley and Alexander Wetmore, who had done work on Hispaniolan birds earlier in the century.

As for Bond’s research, he is perhaps best known for the theory he proposed in 1934 that Caribbean birds were most closely related to North American birds—not South American birds, as had previously been thought. It took Bond almost three decades to convince many zoologists that he was right.

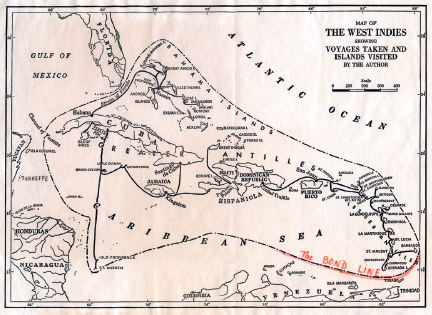

David Lack added “the Bond Line” in red pencil on this map of the West Indies. Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department

“Bond’s Line” has since lost some luster as ornithologists have modified it somewhat, but as Keith Thomson, former president of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and former director of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, points out: “It remains a very significant insight.”

Bond’s other scientific research was far more extensive than most people realize, a fact underscored by the work of zoologist Gerhard Aubrecht of the Austrian Zoological-Botanical Society at the University of Vienna. Aubrecht stumbled across the story of James Bond and Ian Fleming during a trip to Jamaica in 2001 and soon began to collect Bond’s scientific papers—which were published in places as far-flung as Cuba, Tobago, and Peru.

Aubrecht then compiled a database for analyzing different aspects of Bond’s ornithological work in the West Indies. The database, which took more than a decade to assemble, contains more than 24,000 bird records from the West Indies and adjacent islands that Bond mentioned in his scientific papers. In 2017, the Academy of Natural Sciences published Aubrecht’s ten-page “Bibliography of James Bond”—the first ever—which documented 150 papers as well as dozens of Bond’s other publications.

“The way Bond meticulously gathered all the information about the Caribbean birds over decades in a kind of private enterprise is astonishing,” says Aubrecht. “His analysis of all the data and the results he gained make him an outstanding scientist in island biogeography.”

Quantifying the impact of Bond’s work is a bit trickier. In an article for Scientometrics in 2004, Grant Lewison, senior research fellow at King’s College London, assessed the influence of the various editions of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies by using bibliometrics, a statistical analysis of books, articles, and scientific papers. As Lewison pointed out, it’s difficult to assess the value of a book on birds because its readership and citations depend to a large extent on its geographical coverage—a field guide to the birds of North America, for instance, will have a larger impact than one about the Caribbean. Lewison concluded that “Birds of the West Indies has proven to be of enduring scientific interest and to have established its author as an ornithologist of distinction.”

Nate Rice, ornithology collection manager for the Academy of Natural Sciences, concurs: “Anybody who is studying Caribbean birds is going to cite Bond papers. That’s his lasting legacy of scientific importance—how often his papers are cited.”

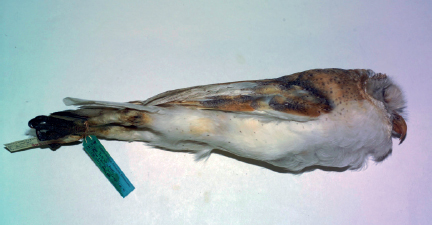

This subspecies of barn owl, Tyto alba bondi, was named after Bond. Photo by Kaylin Martin, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Bond’s first paper, “Nesting of the Harpy Eagle,” appeared in The Auk in 1927. His last, “Twenty-Seventh Supplement to the Check-List of birds of the West Indies (1956),” appeared sixty years later in 1987, two years before his death.

A world traveler for much of his life, Bond was forced to narrow his range in December 1974, when he had surgery for prostate cancer. The cancer returned, and several years later he developed slowly progressing leukemia. Although Bond would live another fourteen years. Mary wrote in To James Bond with Love that there would be “no reading of papers at conferences at London or Basle; no more island-hopping in the West Indies . . . Jim was grounded which presented us with a difficult assignment, but not one that prevented old ties with Caribbean from enduring.”

Frank Gill, another noted ANSP colleague, recalls visiting the Bonds during Jim Bond’s last years. “He was very engaging, keen, with piercing eyes, and he’d look at you and expect a response. He was not a recluse, but he kept a limited circle. He always wanted to talk about birds and the Caribbean. If it was some other topic, his eyes would glaze over and he’d get back to birds. Like Roger Peterson in that regard, and maybe some of the rest of us.”

Bond died peacefully in his bed on Valentine’s Day 1989, far from the possible calamities that threatened his famous namesake—being blown up, poisoned, or tortured by a horde of archvillains who are threatening Western civilization. But even in death he could not escape the 007 connection. Reuters’ obituary, which ran in the Washington Post three days later, characterized Bond as “one of the world’s most famous ornithologists” and began (a bit inaccurately, given Bond’s fondness for shotguns):

The actual James Bond, unlike his fictional namesake, never toted a gun and never drank a martini that was shaken, not stirred. He spied on birds, not beautiful female enemy agents, for a living.

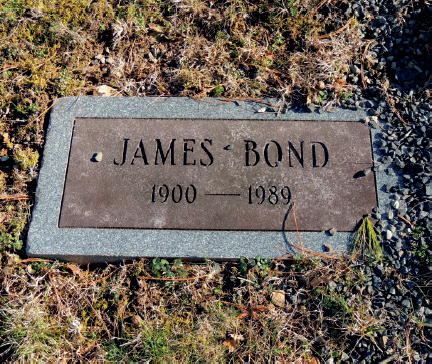

James Bond is buried next to his wife. Mary, in the Church of the Messiah Cemetery in Lower Gwynedd Township, Pennsylvania. Photo by author

Bond’s longtime Academy of Natural Sciences colleague Ruth Patrick summed up Bond’s life more on point: “A really great scientist is a person who devotes their life to their science and it is not a person who is here today and gone tomorrow, And Jim was one of those people. . . . His entire life, once he got into birds, he never lost his drive to understand birds.”

A month after Bond died, former ANSP president Keith Thomson wrote to his widow, Mary: “He will be missed. I don’t know which image is stronger: James as the intrepid traveler to every fascinating corner of the Caribbean—rumpled clothes and uncertain scheduling—or James the precise scientist, immaculately dressed, quiet and thoughtful. Of course, he was all this and much more.”

A Few Accolades

Among the awards Bond accumulated over his distinguished career: the Institute of Jamaica’s Musgrave Medal in 1952 for his contributions to West Indian ornithology, the Brewster Medal (the highest honor of the American Ornithologists’ Union) in 1954, and the Academy of Natural Sciences’ Leidy Award in 1975. Only two other Academy scientists have received the award in its long history.