APPENDIX

001

In Bond’s Footsteps

The Philadelphia skyline, looking northwest along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Photo by author

As part of the research for this book, I visited more than two dozen places where Jim Bond lived or worked, including Pennsylvania, Maine, Cuba, and Jamaica. In the process, I discovered three recurrent themes.

• Almost all of the major landmarks in Bond’s life still stand today, even if some have changed drastically.

• Bond traveled west of his home state only twice in his entire life, but he sure got around. He went to school in England for eight years. He spent most of his summers in Maine. And he traveled to the Caribbean for much of his life.

• No matter how much he traveled, Philadelphia and the Academy of Natural Sciences were his true home.

Here’s a look at James Bond’s old haunts today.

Philadelphia and Environs

1821 Pine Street: The Philadelphia four-story brick house where Bond was born and where the Bond family stayed in the winter in the early 1900s has been divided into apartments.

Academy of Natural Sciences, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. Bond worked in this brick building from 1926 to the 1970s. Several photos of Bond—typically smoking a pipe—adorn the walls of the ornithology department. His corner office, which overlooked the Franklin Institute and Logan Circle, is now an ornithology lab.

Birds, insects, and fish that Bond brought back from the West Indies are part of the institution’s collection of more than seventeen million plant and animal specimens. Fellow contributors to that collection include John James Audubon, Ernest Hemingway, and Lewis and Clark. The academy, the oldest natural-sciences institution in the Western Hemisphere, acquired a new affiliation in 2011 and is now Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

Jim Bond’s birthplace on Pine Street has been divided into several residences. Photo by author

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, where Bond worked for five decades, is home to his archive and many of the birds, fish, and insects he collected in the West Indies. Photo by author

Chateau Crillon Apartment House, 222 South 19th Street, Philadelphia. When Bond lived there before getting married in 1952, the twenty-seven-story high-rise was called the Crillon Hotel. It was designed by Horace Trumbauer, who also designed the Bonds’ Willow Brook estate.

Church of the Messiah, 1001 Dekalb Pike, Lower Gwynedd Township. Jim and Mary Bond’s ashes are buried in the cemetery near the graves of Jim’s mother, brother, and sister. The church’s altar has an exquisite stained-glass window donated by Bond’s father in memory of Bond’s mother. The window, depicting a resurrection scene, was made by Clayton & Bell of London, who also designed several windows for Westminster Abbey.

Bond’s grave is marked with a stone marker that says simply, “James Bond, 1900–1989.” It’s 2 miles from Willow Brook, his childhood home.

Davidson Road, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. The house where the couple lived in the 1960s was designed by noted midcentury architect and sculptor Oscar Stonorov, a German émigré who opened a Philadelphia office with fellow architect Louis Kahn.

In her memoir Ninety Years at Home in Philadelphia, Mary wrote that the house “was built of soft rosy brick, glass, and aluminum tucked into the side of a ravine. The flat roof was but one foot higher than the street.” Bond used to take walks in the nearby Wissahickon Valley Park.

When I stopped by in the spring of 2018, the house appeared to be unoccupied and was in disrepair.

Hill House, 201 W. Evergreen Avenue, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Jim and Mary Bond lived in this eleven-story apartment high-rise by the Chestnut Hill train station from the early 1970s to his death in 1989.

Ingersoll/Clayton House, Old Bethlehem Pike, Spring House, Lower Gwynedd Township. The township now owns the large stone house where Jimmy Bond spent the spring and autumn of 1907 while the family was building a mansion nearby. The house is boarded up, and the grounds are off-limits to the public.

Pennsylvania Bank Building, 1426–1428 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. Bond worked here in the Foreign Exchange Department in his first job out of college in the early 1920s. The bank is now an elegant Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse complete with the original revolving doors at the front entrance, enormous marble pillars, and a special dining area in the vault on the lower level.

The Drake, 1512 Spruce Street, Philadelphia. Jim and Mary lived in a two-bedroom apartment in the thirty-story art deco apartment building after they got married. The living room was large enough for Mary’s grand piano.

Thomas Bond House: Although there’s no record of Jim Bond visiting the home of his ancestor, the cofounder of Pennsylvania Hospital, you can visit—and stay overnight. The four-story brick house, at 129 South 2nd Street in Philadelphia’s Independence National Historical Park, is now a twelve-room bed-and-breakfast decorated in eighteenth-century federal style.

Bond worked at the Pennsylvania Bank after his graduation from Trinity College; the building is now home to a Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse. Photo by author

Willow Brook, 1325 Sumneytown Pike, Lower Gwynedd Township. It’s easy to see how young Bond got hooked on nature during the few years he and his family spent their springs and autumns on this 350-acre country estate. The Bonds planted all sorts of bird-friendly shrubs and trees along what is now known as Rhododendron Drive, and the huge property has all sorts of great bird habitats, from wetlands and creeks to fields and woods.

Even on a mid-January walk around the campus, I saw plenty of avian activity, including nearly a dozen eastern bluebirds, several woodpeckers, two turkey vultures, a red-tailed hawk, and a tree full of American crows. The property was sold when Bond’s widower father remarried in 1913.

Gwynedd Mercy University’s campus has occupied the heart of Willow Brook since 1948. Assumption Hall, the school’s enormous brick administration building, was originally the Bonds’ mansion. The fully restored building later became a convent, and when the nuns invited Jim and Mary Bond back in the 1970s, they had a reception in the house’s formal dining room. Bond told the other attendees that this was the first time he had eaten there—as a child he always had to eat in a dining room set aside for the children.

The university occasionally makes note of the Bond connection, including a video produced by the admissions department a few years ago that features a 007-like Jim Bond searching for the school mascot—a mythic half-bird, half-wildcat known as a griffin.

Willow Brook, Jim Bond’s childhood home, is now part of Gwynedd Mercy University. Photo by author

Mt. Desert Island, Maine

Bond summered here for his entire life, most notably at his uncle Carroll Tyson Jr.’s summer home and nearby hunting camp, and later at a cabin he owned with Mary on Pretty Marsh. The largest island in Maine wasn’t much of a birding destination back when Bond and his uncle wrote Birds of Mt. Desert Island, Acadia National Park, Maine in 1941, but it has become a popular birding spot and home of the annual Acadia Birding Festival.

Bond’s presence on Mt. Desert Island has faded. If you ask at the front desk of the public library in Southwest Harbor or Northeast Harbor, you can see (but not borrow) Bond’s groundbreaking booklet—Southwest Harbor even has a hardbound version of the softcover pamphlet. And you can see the same yellow-covered pamphlet in Acadia National Park’s archives if you make a reservation in advance.

Acadia Birding Festival, Somesville. The popular four-day event has been held annually since 1999, drawing serious birders from as far away as Arizona. Bond’s name is invoked from time to time, but the festival is focused on the present, with dozens of events ranging from guided bird walks (including one to the shores of Pretty Marsh) to talks by big-name guest speakers.

The festival center, in the local firehouse’s community room, offers a wide array of modern field guides, brochures for birding trips to such Bond destinations as Cuba and Jamaica, and binoculars so sophisticated they may have changed Bond’s mind about using a pair (although the tight-fisted Bond would have needed convincing).

Birders at the Acadia Birding Festival look for warblers each June not far from Jim and Mary Bond’s summer residence in Pretty Marsh on Mt. Desert Island, Maine. Photo by author

Birchcroft and Stoneledge, Northeast Harbor. These stately cottages were Carroll Tyson’s summer home base. Bond spent his summers there from the 1910s to the 1950s. The elegant eight-bedroom Birchcroft is still privately owned and enjoyed by seasonal visitors. Tyson painted his celebrated portfolio of Maine birds at Stoneledge, which is also still privately owned. One of those prints, of blue jays raiding a robin’s nest, hangs on a wall on the first floor of Birchcroft.

Pretty Marsh Camp, off Pretty Marsh Road, Pretty Marsh. The cabin and outbuildings where Jim and Mary Bond spent their summers for more than three decades have recently been restored. The property is still privately owned.

Tyson’s Hunting Camp, Long Pond. Tyson’s large home and property, near the water at the base of a steep hill, are still privately owned.

Bond spent many summers at Birchcroft, his uncle Carroll Sargent Tyson Jr.’s home in Northeast Harbor, Maine. Photo by author

Cuba

Cuba figured larger in Jim Bond’s life than in Ian Fleming’s. It was one of the best Caribbean islands for ornithology, with more than 370 bird species, including the tiny bee hummingbird and twenty-six other endemics—species that can be seen only in Cuba. For Fleming, Cuba was a source for villains, notably Major Gonzalez, a Cuban gangster trying to buy up land in Jamaica after Castro’s takeover in Fleming’s bird-filled short story, “For Your Eyes Only.”

Bond visited the island many times, including just after the revolution. In many ways, the island has changed little since then, for better and worse. Cuba is still full of amazing natural beauty and untapped tourism potential.

Playa Larga on the Bay of Pigs is now a resort town. Photo by author

Bay of Pigs. When the Bonds visited in 1960, they scoffed at Castro’s plans to build a resort on the Bay of Pigs. These days, many European and Russian tourists head for the beach town of Playa Larga, where you can enjoy the sandy beach and see a spectacular sunset. You can also watch a neighborhood peddler selling bread door to door from a horse-drawn wagon while 1950s Chevrolets and modern European-built taxis zip past—a taste of three centuries all at once.

Havana. Cuba’s capital is reminiscent of Jim Bond’s Philadelphia of the 1950s in one major way: the same American cars spewing thick fumes.

The Presidente, the hotel where Jim and Mary Bond stayed, is still owned by the government, but the room rates are no longer $5.10 a night—they list for closer to $200.

The Cuban tody, which graced the front of the dust jackets for Bond’s 1936 and 1947 editions of Birds of the West Indies, is still abundant in the Zapata Swamp. Photo by author

Zapata Swamp. Cuba is rightly proud of the Zapata Swamp and the 2,425-square-mile Ciénaga de Zapata Biosphere Reserve, considered by UNESCO to be one of the largest and most important wetlands in the Caribbean region. But back in the days before Cuban expatriates funded by the United States invaded in 1961, Fidel Castro wanted to clear the swamp and use the land to grow sugar cane. Fortunately, the Zapata Swamp remains wilderness.

On a visit in November 2016 with the Caribbean Conservation Trust, a nonprofit group that does regular bird surveys in Cuba, I visited the swamp in hope of seeing two of the swamp’s most famous residents, the Zapata wren and the Zapata sparrow. A third celebrated resident, the Zapata rail, had rarely been seen or heard in recent years. All three were Bond’s target birds (literally and figuratively) back in the late 1920s.

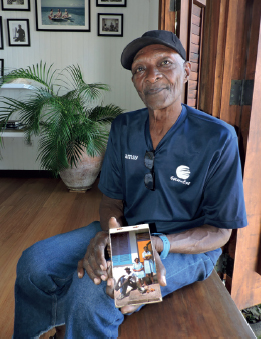

Helping lead the way was Frank Medina, the Cuban official who runs the reserve. A tourist from Canada had given Medina her copy of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies on a visit in the early 1980s, and that was how he learned about his nation’s birds.

While we were looking for the wren and sparrow—successfully, it turned out—a Cuban tody appeared, seemingly from out of thin air. The Zapata wren and Zapata sparrow may be far rarer, but the Cuban tody is the showstopper, a miniature living, breathing rainbow of bright pastels. When Mother Nature was handing out beauty to the bird kingdom, the Cuban tody came back for a second helping. No wonder Bond put it on the cover of the 1936 and 1947 editions of Birds of the West Indies and featured it on the full-color frontispiece as well.

Jamaica

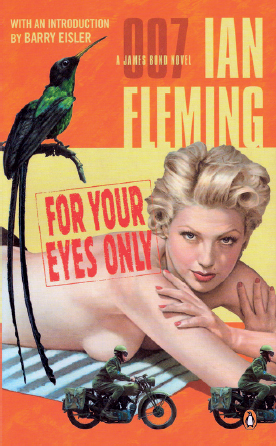

To understand Jim Bond or Ian Fleming, you had best visit Jamaica. For Fleming, the island was both sanctuary and workplace. Not only did he invent his fictional James Bond and write all of the 007 novels in Jamaica at Goldeneye, but the island nation also provided the setting for Dr. No, Live and Let Die, and The Man with the Golden Gun, as well as the short story “For Your Eyes Only,” which starred red-billed streamertails. This is where Fleming was happiest.

For Bond, Jamaica was one of the key islands of research for Birds of the West Indies. The attraction was clear. Jamaica was, and is, known as a biodiversity hotspot where you can find birds you’ll likely see nowhere else. It ranks fifth among the world’s islands for endemic species. By one count, the island has twenty-nine endemics. The island nation, which remained a British colony until 1962, is also the place Bond and his wife kept returning to long after his research days were over, for the same reason that two of America’s finest nineteenth-century artists, Frederic Edwin Church and Martin Johnson Heade, kept returning: the island is flat-out beautiful.

This 007 paperback featured a streamertail, the national bird of Jamaica and a Fleming favorite. Front cover in its entirety from For Your Eyes Only by Ian Fleming (Penguin Books, 2006). Copyright © Penguin Books Ltd., 2006

What is known of Bond’s travels in Jamaica is largely the result of Mary’s memoirs, and it’s clear that two Jim Bonds visited Jamaica, the youthful explorer who roughed it in the 1930s, and the older ornithologist of the 1960s and early 1970s. The younger Bond traveled by foot or mule, ate with local farmers, and slept in hammocks. The older Bond and his wife traveled in style by car, sipping cocktails and staying at hotels that were once the great houses of Jamaica’s old sugar plantations.

These stately homes and their vast estates were also favorite haunts of Ian Fleming, who stayed at his buddy Ivar Bryce’s great house, Bellevue, on his first visit to Jamaica in 1943—for a conference on combating the Nazi U-boats that were wreaking havoc on shipping in the Caribbean.

For the boastful Fleming, the great houses also provided a challenge. According to biographer John Pearson, Fleming once wrote that he was determined that Goldeneye would become better known than any of the great houses “that had been there so long and achieved nothing.” One can argue about the great houses’ historical value, but the past and present Goldeneye is the best known.

Blue Mountains. In eastern Jamaica, these mountains and their smaller cousins, the John Crow Mountains, dominate the landscape. They are not only steep, with a top elevation of 7,400 feet, but they are also on Kingston’s doorstep.

How the Blue Mountains got their name is unclear, although many believe it’s because of the blue-gray clouds that often shroud parts of the mountains. Up close, the terrain is several shades of green, as lush and vibrant as any tropical rainforest. Fleming, a world traveler, described the Blue Mountains as the most intoxicating landscape he’d ever seen.

These mountains are also where both Bond and Fleming went to find rare birds. And that wasn’t easy back in the day. According to Matthew Parker in Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born, Fleming described being dragged somewhat unwillingly from “the sunbaked sand of my pirate’s cove” to ride donkeys up the mountain. In the 1930s Bond likely traveled up the mountain by horse, mule, or donkey as well.

Ramsey Acosta, one of Fleming’s gardeners at Goldeneye, says Jamaica’s roads back in the thirties “were very bad. There were asphalt roads only along the coasts where the tourists traveled.” Even today, the narrow, two-lane roads that thread their way over the Blue Mountains are a challenge to navigate, but for birders in search of mountain witches, Jamaican owls and rufous-crested solitaires (the bird with the haunting call for which Ian Fleming named his femme fatale in Live and Let Die), this is heaven.

Ramsey Acosta was Fleming’s gardener at Goldeneye for many years. Photo by author

A view of the GoldenEye Resort in Jamaica. Photo by author

Exterior view of Fleming’s Jamaica home, now a coveted part of the GoldenEye Resort. Mark Collins photo, courtesy of Island Outpost

GoldenEye. On the North Coast Highway, not far from the Ian Fleming International Airport and James Bond Beach, sits Ian Fleming’s former getaway. When Jim and Mary visited, she described it as a small property tucked away on an isolated promontory outside the little town of Oracabessa: “We found the white gates hospitably ajar between two pink plaster gate posts,” she wrote in To James Bond with Love. “The gravel driveway dwindled to a mossy track that ended at a low rambling house where, in true West Indian fashion, a long hibiscus hedge was strewn with towels and napkins spread out to dry.”

Fleming’s friend and neighbor, Noel Coward, described it this way to Fleming biographer John Pearson: “Goldeneye, of course, is a positively ghastly house. I should know. Ian lent it to me for three months the year after he’d built it (and charged me fifty pounds a week for the privilege, I might add, and as I told him, that was too much for bed and board in a barracks). There was no hot water in those days. Only cold showers. We were very manly and pretended to like it.”

Coward liked to joke that the austerely modern bungalow looked so much like a medical clinic that it should be called “Golden Eye, Nose and Throat.”

Although criminals are notorious for returning to the scene of the crime, it turns out that in the case of Fleming’s identity theft, the victim returned as well. On their final trip to Jamaica in the early 1970s, Jim and Mary Bond stopped by to give Fleming’s housekeeper, Violet Cummings, a copy of Mary’s How 007 Got His Name. Mary later recounted in To James Bond with Love that although much about the place remained unchanged, down to the towels drying on the hibiscus, she concluded that “the fun was over without Fleming around, and we drove away.”

But times change, and Goldeneye’s “white gates hospitably ajar” have given way to a high metal fence and locked black iron gates and a guard at the sentry post just beyond the entrance—befitting its current status as an ultra-exclusive seaside resort. The driveway, no longer mossy, splits just beyond the entrance. To the right is the private driveway to Fleming’s original home, now called the Fleming Villa. To the left is the main thoroughfare leading to the main office and the many luxury villas, cottages, and huts, most of which are on their own separate island. It is as close to a tropical paradise as one is likely to encounter anywhere.

A mango tree donated by 007 actor Pierce Brosnan is part of the resort. Photo by author

In true Jim Bond fashion, I tried to do some birding while I toured the grounds, with an eye out for the Jamaican grackles that had upstaged Fleming during his Canadian Broadcasting Corporation interview more than a half century earlier. At the resort’s waterside Bar Bizot, I found several of them, still making their distinctive two-note “kling, kling” call, and still up to their usual tricks. Two were hopping about on a table freshly set with silverware, plates, and water glasses, with one of them pulling on a white linen napkin apparently just for the fun of it.

While paying due tribute to its previous owner, down to copies of many of the 007 books in each villa, cottage, and luxurious hut, the resort is as much about the movie 007 as the literary 007, and that’s as it should be. The cinematic James Bond can reinvent himself every few years, whereas Fleming’s literary 007 is frozen in time with both his flaws and strengths. It’s significant that the Ian Fleming Room, just a few yards from the old gazebo, features a huge black-and-white photo of Fleming and the original cinematic 007, Sean Connery. It was no doubt taken at the old Goldeneye or the nearby stretch of sand now known as James Bond Beach. To choose a photograph that features Connery so prominently is perhaps an acknowledgment that visitors might need a little visual cue to recognize that Ian Fleming is in the photo as well. Both author and resort can bask in Connery’s radiance. Ultimately, the fictional 007 has upstaged his creator in much the way 007 upstaged Jim Bond so many years ago. Fleming’s most iconic secret agent remains larger than life, while Fleming and Bond were mere mortals.

The beach where key scenes of the movie Dr. No were filmed is now called, appropriately, James Bond Beach—complete with restaurant, bar, and Wi-Fi. Photo by author

GoldenEye is a reflection of its owner, Chris Blackwell, who knows how to pamper the superrich, but it is also a projection of what the old Goldeneye might have become if Fleming had had more time and money. Although Fleming had built the original Goldeneye in a spartan manner, he always admired both luxury and sophistication and made them 007 staples. Today’s GoldenEye would suit him just fine.

Mona Great House, on Great House Boulevard, a mile from the University of the West Indies campus. It was from here, on February 5, 1964, that Jim and Mary hired a driver to take them on their surprise visit to Goldeneye.

In To James Bond with Love, Mary described the Mona Hotel as such:

This . . . was another beautiful Colonial Great House built on a knoll four miles outside of Kingston, standing like an elegant grande dame aware of her dignified past. Beyond the terraced gardens the fabulous Blue Mountain range, fold upon fold, caught the ever-changing light of day, composing patterns of color as grand as the greatest symphonies. Two ancient and magnificent mango trees, one on each side of the house, provided shade for tables and chairs, which made a rum swizzle with a sandwich lunch or evening cocktails moments to be remembered.

Mary also lamented that “the Mona Great House was being surrounded with a townhouse development. No use wringing our hands. We could only wonder when the lovely house with its vine-covered walls and white pillars would, itself, be demolished.”

She would be pleased to know the great house still stands, and so do the mango trees on either side of it. As she feared, housing obstructs the view of the mountains, and the road through the development runs right next to the great house, depriving it of its front lawn and its former spectacular setting.

The Mona Hotel, a favorite of Jim and Mary Bond’s when they visited Jamaica, is now a private residence. Photo by author