After three centuries of Spanish rule, Mexico finally broke away and declared itself a republic on September 27, 1821. Coincidentally, secularization of the missions was then sought by Spanish-Mexican settlers, known as Californios, who complained that the Catholic Church owned too much of the land. Eight million acres (3.2 million hectares) of mission land were fragmented into 800 privately owned ranches, with some governors handing out land to their cronies for only a few pennies per acre.

Pull Away Cheerily: The Gold Digger’s Song, by composer Henry Russell, was about the Australian and Californian gold rushes.

Lordprice Collection/Alamy

Life under the Californios

Orange orchards were cleared for firewood, herds were given to private hands, and the predominant lifestyle quickly changed to that of an untamed frontier-style cattle range. Cattle ranching in this part of the world, however, made few demands upon its owners. With no line fences to patrol and repair on the open range, and no need for vigilance because of branded stock, the vaquero had little to do but practice feats of horsemanship to prove his masculinity and impress the señoritas.

The vaquero’s sports were violent, including calf branding, wild-horse roundups, bear hunts, and cock- and bullfights. His entertainment included dances, and at his fiestas he was bedecked in gold-braided clothes dripping with silver.

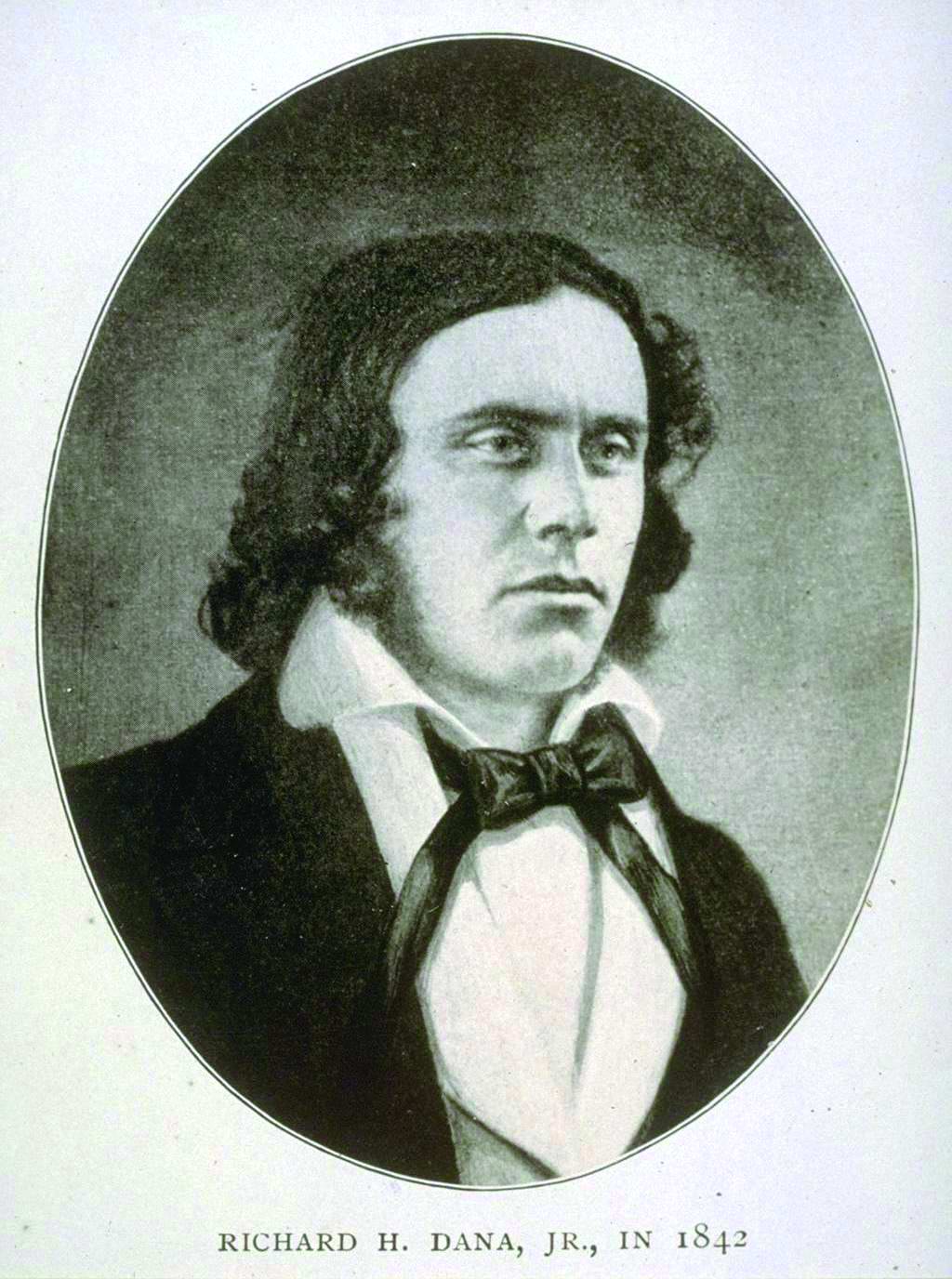

Author Richard Henry Dana, who visited the state in 1835, called the Californians “an idle thriftless people,” an observation lent considerable weight by the lifestyle of so many of the rancheros, who found it a simple matter to maintain and increase their wealth. The sudden influx of prospectors to the north created an immense demand for beef, which the southerners were readily able to supply.

An 1842 portrait of Richard Henry Dana, author of the influential Two Years Before the Mast.

Public Domain

Yankee trading ships plied up and down the coast, operating like floating department stores offering mahogany furniture, gleaming copperware, framed mirrors, Irish linen, silver candlesticks, and cashmere shawls. These trading ships were the first opportunity for many native-born Spanish settlers to obtain jewelry, furniture, and other goods from the old world. Sometimes the trading ships, which had survived the precarious Straits of Magellan, would stay an entire year.

A genteel contraband soon developed. To reduce import taxes, ships worked in pairs to transfer cargo from one to the other on the open seas. The partially emptied ship would then make port and submit to customs inspection. With duties paid, it would rejoin its consort and reverse the transfer. Sometimes the Yankee traders used lonely coves to unload their cargoes, which were eventually smuggled ashore. The weather remained temperate except for the occasional hot, dry, gale-force wind the Native Americans called “wind of the evil spirits.” The Spaniards called them santanas, a name which today has become corrupted to Santa Ana winds. Now and again an earthquake rumbled down the San Andreas fault. The rancheros spent their energy rebuilding damaged haciendas, made from red-tile roofing set on white-painted adobe brick walls. The missions, meanwhile, fell into ruins: restoration of the missions began only in the 20th century after they were declared historical landmarks.

After the Battle of Monterey, Mexican General de Ampudia surrenders to American General Taylor during the Mexican-American War of 1846–8.

Getty

Soldiers who’d finished in the army often stayed in California rather than return to Spain or Mexico. Under Mexican law, a ranchero could ask for up to 50,000 acres (20,200 hectares); native slave labor became part of the plunder.

In 1834, Governor Figueroa issued the first of the Secularization Acts, which in theory gave lay administrators and Indian neophytes the right to ownership of the missions and their property. Having been first introduced to the “civilized” world and then enslaved, the native peoples were disoriented. At the height of the mission era, as many as 20,000 Indians had been tied to the system as unpaid laborers, and were now psychologically ill-prepared to cope with freedom.

The Mexican–American War

Official Washington soon became aware of this land of milk and honey on the Pacific coast. President Andrew Jackson sent an emissary to Mexico City in the 1830s to buy California for the sum of $500,000. The plan failed.

When James K. Polk took office in 1845, he pledged to acquire California by any means. Pressured by English financial interests that plotted to exchange $26 million of defaulted Mexican bonds for the rich land of California, he declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846.

News of the war had not yet reached California, however, when a group of settlers stormed General Mariano Vallejo’s Sonoma estate. Vallejo soothed the men with brandy and watched as they raised their hastily sewn Bear Flag over Sonoma. The Bear Flag Revolt is sanctified in California history – the flag now being the official state flag – but for all its drama, it was immaterial. Within a few weeks Commodore John Sloat arrived to usher California into the Union.

In addition to being denied legality and having their labor exploited and their culture destroyed, the Native Americans had been fatally exposed to alcoholism and all manner of foreign diseases.

Most of the fighting took place in the south. The war in the north effectively ended on July 9, 1846, when 70 hearty sailors and marines from the ship Portsmouth marched ashore in Yerba Buena village and raised the American flag in the village’s central plaza, now Portsmouth Square in San Francisco.

The bloodiest battle on California soil took place in the Valley of San Pasqual, near Escondido. The Army of the West, commanded by General Stephen W. Kearney, fought a brief battle during which 18 Americans were killed.

Kearney’s troops skirmished with Mexican–Californians at Paso de Bartolo on the San Gabriel River. The Californios, however, soon capitulated to the Americans, and California’s participation in the Mexican–American War finally ended with the Treaty of Cahuenga, signed by John Fremont and General Pico.

The treaty came into force on July 4 (US Independence Day), 1848, and made California a territory of the USA. Only through fierce negotiation was San Diego placed on the north side of the Mexico–California border.

For three decades after America had acquired Alta California in 1848, Los Angeles remained a predominantly Mexican city infused with a Latino culture and traditions. But the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad triggered a series of land booms with the subsequent influx of Anglo-American, Asian, and European immigrants eventually outnumbering Mexicans 10 to 1.

Meanwhile the Native American population continued to suffer. From 1850 onwards the Federal government signed treaties (never ratified by the Senate) under which more than 7 million acres (2.8 million hectares) of tribal land dwindled to less that 10 percent of that total. Next to suffer from marginalization and racist attitudes were the Chinese, thousands of whom had poured into Northern California from the gold fields and, later, into Los Angeles after the railroads had been completed.

California was rushed into the Union on September 9, 1850, as the 31st state, only 10 months after convening a formal government. But it had already drafted a constitution that guaranteed the right to “enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness,” with hindsight a typically Californian mix of the sublime and the practical.

The California flag.

Elswarro/Dreamstime.com

The Pony Express

When California gained statehood in 1850, mail from the East took six months to deliver. Overland stagecoaches cut this to less than a month, but in 1860, the sinewy riders of the Pony Express brought San Francisco much closer to the rest of the nation. Mail travelled over hostile territory from St Joseph, Missouri, to the young city of San Francisco in only 10 days. Riders had just a revolver, water sack, and a mail pouch, the most famous of them being 15-year-old William “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Just as quickly, though, came the Transcontinental Telegraph, and on October 26, 1861, the Pony Express closed its doors.