11

The Republican Triumph and the Clinton Surrender

In the middle of 1994, a relatively good year for the economy, a record low percentage of the people went to the polls and voted to repudiate the Clinton administration and the Democratic Congress, thereby giving the Republicans a chance to deliver on their Contract with America. Why was such good economic news associated with such a massive repudiation? During the first two years of the Reagan administration, the changes Reagan began to implement combined with the Volcker anti-inflation policy to produce the 1981–82 recession. Republicans suffered heavily in those midterm elections. There was no similar dramatic economic failure in 1994, yet the voters reacted more negatively to the Clinton administration than they did to Reagan and the Republicans.

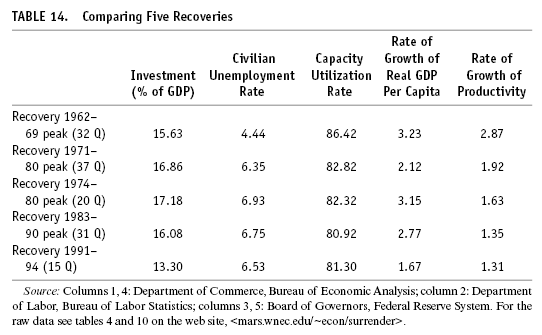

Perhaps we might gain some understanding of this if we compare the recovery since the first quarter of 1991 with the Reagan-Bush recovery of 1982–90 and with the 1971–80 and 1974–80 recoveries (see table 14).

The macroeconomic picture is very mixed. In terms of unemployment and capacity utilization, there is an improvement over the Reagan-Bush years, but not over the 1971–80 period. In measuring investment as a percentage of GDP, the rate of growth of real per capita GDP, and the rate of growth of productivity, the table reveals the worst averages of the recovery periods we have investigated. Perhaps the voters’ anger reflects the cumulative effect of two decades of unacceptable economic performance. Even the best of the macroeconomic numbers from the period since 1991 have not compared favorably with the period that has come to be the standard for success, the postwar boom of 1945 to 1969, which included the period we have called KJN, the 1962–69 recovery.

From the perspective of the public’s disappointment with the overall performance of the economy, there are two alternative explanations for the failure of the Clinton economic policy. Was the policy a failure because it reversed Reaganomics, thereby continuing the disastrous Bush approach that raised marginal tax rates and imposed increased regulation while failing to get the budget deficit under control? Alternatively, was the Clinton policy a failure because it did not reverse Reaganomics, thereby continuing the disastrous trends of rising inequality, creation of more and more low-paying jobs, and reduction in the number of higher-paying jobs, despite the decline in unemployment?

Beyond these issues, there was also a growing feeling of insecurity among workers about their jobs as well as the increases in inequality and sluggish growth of real income. The pace of change, financial instability, corporate downsizing, increasing international competition, and awareness of the increasing percentage of the population without health insurance all combined to make the public feel less secure and more anxious about the future. This anxiety focused on the problems that politicians and opinion molders identified—the budget deficit, rising welfare rolls, wasteful, intrusive government activity. For many citizens, worries about layoffs, loss of health insurance, and falling values of homes became linked to the economic failures of government policy. Thus, the complaints of H. Ross Perot in the 1992 presidential campaign were echoed in the Republican criticisms of the Clinton administration. Poll after poll indicated that huge majorities of Americans believed it was essential to balance the federal budget, even if this required a constitutional amendment.

Two things are apparent from table 14. There is continued evidence for the relative unimportance of both marginal tax rates and regulatory burdens in determining the overall rate of productivity growth. We know that the marginal income tax rate did increase significantly (for some taxpayers, to 42.5 percent), and it is also relatively clear that the regulatory burden of the Americans with Disabilities Act was continuing to grow as legal issues were settled. Thus it would be safe to assume that from an incentive “supply-side” point of view, productivity growth ought to have been damaged by both the Clinton changes and the continued increase in regulatory activity begun in the Bush administration.1 Yet the productivity numbers are only marginally different from those of the 1982–90 recovery.

In contrast to these public perceptions, the Clinton administration took a more positive stance. In 1995, a year after the Republican victory, the Council of Economic Advisers argued that its policies were already working quite well. They pointed to the lowest misery index in over twenty-five years,2 an improvement in productivity and the creation of a significant number of jobs. The Republicans were blamed for the public discontent; they had worked to destroy the initiatives of the Clinton administration and then, in October 1994, complained to the voters that nothing could get done in Washington. This explanation fell on deaf ears, however, because the voters knew that both houses of Congress had Democratic majorities. Despite the continued efforts of the Clinton administration to identify economic successes and to place blame on Republican “demagoguery,” the public’s conclusion, voters as well as those from the core Democratic constituency too disillusioned to vote, was that the “economic policy” successes had not translated into any improvement in their lives.

Consider the creation of new jobs. Between January 1993 and December 1994, the economic recovery had increased total employment by 7.4 million jobs.3 However, with the continuation of corporate downsizing, the shrinkage of federal defense spending, and pressure on state and local budgets, this net increase appears to have masked a further decline in the availability of well-paying jobs. Certainly the trends in wage inequality were not reversed during those first two years. Average weekly earnings, which had declined 3.5 percent between 1989 and 1993, rose a minuscule .7 percent in 1994.4

Failure of Health Care and Welfare Reform

The biggest failure of the Clinton administration was in the area of health care reform. After months of study, an administration task force headed by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton recommended a system of universal coverage through private insurance companies. All individuals would be required to buy health insurance. Except for those employed by large corporations who could negotiate packages directly with insurance companies, everyone not covered by Medicare would purchase coverage through regional “alliances” that would be able to bargain with health care providers for reduced rates of coverage. Every insurance package would have to offer the same set of comprehensive benefits. Certain practices of insurance companies designed to minimize their risks, such as refusing to enroll people with a “preexisting condition,” or refusing to cover some highly expensive procedures or treatments, would be outlawed. The goal of this proposal was to eliminate the possibility that price controls in one area of health care financing (for example, in Medicare and Medicaid) would translate into higher prices in another area (such as group health insurance for the corporate sector). With everyone covered by insurance and all purchasers of coverage united in various alliances or large corporate entities, price inflation would be moderated as insurers vied for the lucrative contracts with various alliances and as providers vied for the lucrative contracts with insurance companies.5

This proposal illustrated the same contradictory impulses that had plagued the combined stimulus package and deficit reduction plan in the first months of the Clinton administration. The administration wanted to create a universal system of health insurance with a generous guaranteed package. At the same time they wanted to control inflation of medical costs. The Reagan Revolution followed by the 1990 recession and a sluggish recovery had bequeathed high budget deficits and, more importantly, a policymaker’s consensus that deficit reduction was essential for future prosperity. Thus, increased spending without offsetting savings or revenue increases would not meet the “deficit neutral” test that had been imposed on policymakers. Unfortunately for reformers, using new tax revenue to finance significant increases in federal spending was also virtually impossible in the post-Reagan era. Even the 1993 tax increases that had been specifically targeted at deficit reduction had barely squeaked through Congress.

In order to make sure that there were significant cost controls in the reformed health care system, the proposal required the creation of regional health alliances, new regulatory bodies. Some form of taxation was needed to finance the coverage of the poor, whether employed or unemployed. Though the Medicaid program would become part of the comprehensive program, it was clear that the savings in Medicaid expenditure would be far less than the added expense of insuring all the uninsured. This approach would limit choice of physicians and even treatment availability. This last factor was already of growing concern within the health care delivery system as more and more companies began to shift their employees into “managed care.” The Clinton program promised a significant acceleration of these moves into managed care.

The plan was an easy target for groups whose incomes would suffer as a result. Because of the cost constraints, average citizens saw many new regulations but no new infusion of federal dollars. Thus, it was hard for people who already had employer-provided health insurance to see benefits in this proposal for themselves and their families.6 Early positive responses to the president’s speech and the First Lady’s testimony before Congress in support of the plan quickly faded as the insurance industry and other special-interest groups launched highly effective advertising campaigns with the theme, “There’s got to be a better way.” Members of Congress joined in, and, in the end, there was no consensus for comprehensive reform.7

Clinton would have had a better chance of success or, failing that, an opportunity to explain the reasons for his failure if he had presented a bold option for the creation of a Canadian style single-payer plan that abolished the role for private insurance in the financing of health care. The single-payer plan, introduced in Congress with a significant number of sponsors but never seriously discussed in the national media, would have financed all health care expenditures with a payroll tax and paid all health care providers according to prices negotiated by each state. Individuals would have had complete freedom of choice of physicians and hospitals who, in turn, would bill the state for all medical procedures at the prevailing price.

Such a system combines universal coverage with price controls. The price controls are not, however, imposed externally to the market; they are negotiated between the purchaser (each state) and the seller. An individual “pays” for health care by simply running an identifi-cation card through a scanner. This type of system has worked quite well in Canada. The problem with such a system is that it takes billions of dollars in revenue away from the insurance industry and potentially reduces the income of specialists in the medical profession.8

In order not to provoke these powerful groups, the Clinton administration chose to propose the more complicated system.9 They hoped the insurance industry and the medical profession would support their proposal over the more radical single-payer plan. Yet once the initial momentum in support of reform had run out and Congress proved incapable of uniting behind any version of the initial proposal, the opposition was able to raise the specter of “socialized medicine,” successfully hookwinking the public. Through public-opinion polls, people supported the elements in the Clinton reform, coverage for all, cost containment, private insurance, while at the same time voicing opposition to the “Clinton plan,” the details of which they did not know. With the danger of a “worse deal” banished by a combination of media blackout and Clinton administration abandonment, the insurance industry and medical profession had no reason to accept the “better deal” the administration had proposed when they could settle for what they preferred, the status quo.

One side effect of the failure of health care reform was that Medicare and Medicaid costs were projected to continue rising faster than the rate of inflation. This forced the administration to propose a budget plan in 1995 that predicted no reduction in the federal deficit below $200 billion for the foreseeable future.

In the 1994 campaign, the Republicans were helped by the inability of Congress to reform health care. They were able to argue that the Democrats had had a chance with the presidency and control over both houses of Congress and had failed to accomplish anything except raising taxes. Once the new Congress arrived in January 1995, they set the agenda not just with moves to balance the budget but with an effort to “end welfare as we know it,” Clinton’s campaign promise.

The Clinton version of that proposal, which had never even reached the stage of congressional hearings, was one that attempted to move able-bodied welfare recipients into the labor force by imposing time limits on the receipt of AFDC payments. The problem with the Clinton version is that it increased expenditures for child care and job training.10 The Republican proposal meant abolishing the federal guarantee of entitlement and turning AFDC over to the states. With a fixed federal block grant to help them finance their own versions of welfare, the states would be given great latitude in setting eligibility standards, time limits, and so on. That latitude only permitted increasing stringency. The Personal Responsibility Act promised to deny AFDC to women under eighteen who had children out of wedlock, and to force states to begin moving welfare recipients into the labor force after two years on aid. It also put a lifetime cap of five years on the receipt of AFDC.11 The idea of turning over AFDC to the states had been prominently featured in Ronald Reagan’s “New Federalism” proposal advanced in his State of the Union speech in 1982.12 At that time governors were uninterested in taking on new responsibility without the federal cash to support it. Public-opinion polls also showed that citizens believed that it was a federal responsibility to set welfare standards.13

During the Clinton administration, basic federal responsibility to set standards and provide funding remained intact, while opportunities for states to experiment were greatly expanded, as provided by the Family Support Act of 1988. By 1996, forty of the fifty states had received some kind of waiver from the Department of Health and Human Services from the specific requirements of federal law in order to experiment.14 Among the most prominent were the Wisconsin and Michigan reforms, in which Republican governors Tommy Thompson and John Engler were promoted as potential vice presidential nominees because of their alleged successes in reducing welfare rolls and finding employment for former recipients.

However, President Clinton vetoed the national Republican proposal in January 1996 because it was allegedly “too extreme” in the rigidity of its time limits, in its failure to provide child care and aid for disabled children, and in its removal of the federal guarantee of food and medical assistance. The Washington debates and the presidential vetoes once again masked a fundamental change. Through his approving of so many waivers, the president indicated that he would ultimately sign a law that ended “welfare as we know it” even if it did not contain the extra money that he originally thought was necessary to enact real reform. Despite the denunciations of some House and Senate Democrats that this was abolition, not reform, Clinton agreed to sign a modified bill in August. From the point of view of the administration, this bill was a marked improvement over the one Clinton had vetoed. The bill preserved the federal guarantees of food stamps and Medicaid even for those terminated from the AFDC program. It increased the budget for child care to assist welfare recipients who work. However, of much greater significance was the transformation of Clinton’s original proposal to reform welfare by spending more money on child care and job training into a program that guaranteed cuts amounting to $55 billion over six years. Instead of reforming welfare, he had abolished it, turning it over to the states with inadequate funds to maintain services.15

In a December 1996 news conference, President Clinton acknowledged that

there are not now enough jobs available, particularly in a lot of urban areas, for all the able-bodied people on welfare when they run out of their two-year time limit under the new law.

His solution was to

provide special tax incentives and wage subsidies and training subsidies to employers to help hire people off welfare and to help the cities with a lot of welfare case load.16

He argued that his new fiscal 1997 budget plan included sufficient monies to fix this and other problems with the welfare reform bill. As part of the 1998 budget agreement with Congress, Mr. Clinton was able to restore $13 billion of the $55 billion spending reduction in the Personal Responsibility Act, most of it in restored SSI benefits to legal immigrants.17

The Final Surrender: Budget Balance by 2002

Unable to succeed with health care reform and appearing to be dragging its feet on welfare reform, the Clinton administration was battered for much of 1995 by Republican taunts that it had abandoned the fight for fiscal sanity by proposing a budget plan that saw deficits of $200 billion a year for the foreseeable future. This led the administration to abandon all of the arguments it had made in 1994 and 1995 that a push to balance the budget by a date certain would do more harm than good. In April 1995 it proposed its own version of a balanced-budget strategy. From then through November 1996, the major battles in economic policy were fought out over which path to a balanced budget was more realistic. The Republicans proposed tax cuts of approximately $230 billion over seven years and spending cuts approaching $480 billion over that same period to achieve balance by 2002.18 The administration countered with a nine-year plan that cut taxes approximately $90 billion and cut spending a lot less than the Republicans to achieve balance by 2004. After November 1995, the Clinton administration proposed its own seven-year balanced-budget plan, accelerating the cut in spending but presenting more optimistic figures for revenue growth than the Republicans. By January, the administration had readjusted its figures to conform to the more pessimistic projections of revenue growth by the Congressional Budget Office.19

What is interesting about this debate is that there is nothing in the move toward a balanced budget that guarantees rising incomes for the vast majority of Americans, even if all the reduced aggregate demand from reduced government spending is countered by rising private investment.20 The American economy had experienced significant levels of investment spending over the previous fourteen years. Yet between 1983 and 1997, the percentage of personal income received as wages and salaries fell from 58.1 percent to 56.4 percent. In manufacturing industries the fall was even greater, from 13.8 percent of personal income to 10.3 percent.21 In 1989, the share of wages in personal income was 57.8 percent, only slightly lower than in 1983. The manufacturing share was 12.2. Thus, the increasing inequality through 1989 if anything had accelerated. Meanwhile, the share of corporate profits in national income went from 7.6 percent in 1983 to 7.9 percent in 1989 to 10.8 percent in 1996. After-tax corporate profits increased only a little less, falling from 4.9 percent in 1983 to 4.7 percent in 1989 and then rising to 7.2 percent in 1996.22 As demonstrated in chapter 9, the rise in productivity that did occur after the 1970s was more unequally distributed than previous increases in productivity since World War II.23 Much of that inequality has been the result of increasing wage inequality, not merely the rising share of profit and declining share of wages and salaries.24

In the 1995 Economic Report the Council of Economic Advisers identified four potential reasons for wage stagnation and rising inequality. One was the “shift in the demand for labor in favor of more highly skilled, more highly educated workers.”25 Two additional reasons were the decline in the percentage of the workforce that is unionized and the decline in the purchasing power of the minimum wage. Finally, in discussing increased international competition, the council cited studies that found that international competition played a relatively small role in the above-mentioned shift in demand for workers. However, it did acknowledge that the threat of international competition may have played a role in holding down wage increases, a problem that may increase as international trade grows in importance.26

The solution proposed was based on the argument that inequality has increased between those with college education and those without one. The proposal involved the expansion of educational opportunities for all Americans and institutional reforms designed to ease the transition from school to work and to facilitate retraining when workers change jobs.27 Let us recall that the only way this will raise the number of high-pay, high-quality jobs in the United States is if we accept Robert Reich’s proposition that the businesses of the world are creating such jobs at a very high rate and they will locate those jobs where a high-quality labor force exists. Otherwise, if there is no absolute increase in the rate of growth of high-quality jobs, then the only result of increasing the skill levels of the next generation of American workers will be to glut the market for such high-quality people and cause their incomes to become depressed.

Thus, Clinton’s policies of omission failed to reverse the growth of inequality. The overall measurement of inequality called the Gini ratio (0.0 would be a perfectly equal distribution; 1.0 would involve only one person monopolizing all of the income or wealth or whatever was being measured) for both family and household income rose from 1991 through 1993 and fell very little through 1995.28 By 1996, the issue of rising inequality actually forced its way into the presidential campaign. Republican candidate Patrick Buchanan used strident, populist rhetoric to attack free-trade policies, the financial bailout of Mexico, and immigration as causes of the stagnation in the living standards of American workers. In the context of highly publicized corporate downsizing and the apparent rise in the economic health of the largest corporate enterprises in the country with generous rewards received by CEOs of these businesses, these attacks seemed to be proposing what some saw as a dangerous revival of “class warfare,” this time coming, not from the Democrats, but from a self-described conservative Republican.

The Clinton administration responded with a report from the Council of Economic Advisers that attempted to allay the fears of the average American. Despite the well-publicized shrinkage of employment in high-profile large corporations, there had been so much new job creation among small companies that on average there had been significant job creation. The council remarked that “nonfarm employment grew by 8.5 million (7.8 percent) between January 1993 and March 1996.”29 More to the point, a very high percentage of these new jobs were claimed to be in high-wage occupations: “Two-thirds (68 percent) of the net growth in full-time employment between February 1994 and February 1996 was found in job categories paying above-median wages.”30 Contrary to the view that much job growth involved involuntary part-time work, the council found that most of the newly created jobs were full time and that there was no increase in the percentage of the employed who held more than one job.31

Among the economic pundits, Newsweek columnist Robert Samuelson was particularly vocal in arguing that the average American actually was doing quite well economically. According to Samuelson, there had been no observable increase in job insecurity, and real family incomes had been rising decade after decade. In short, the rising feeling of insecurity was a psychological problem, not an economic problem.32 Yet 1995 and 1996 were years where such anxiety continued to resonate. The Council of Economic Advisers’ 1996 report acknowledged that the United States still faced the economic problems of slow productivity growth and rising income inequality.33 These words were written fully three years after the Clinton administration took office with a blueprint summarized in A Vision of Change for America designed to deal with these problems. Though references were made to indications that “we may be beginning to succeed in sharing the benefits of growth and reducing poverty,”34 much of the focus of the 1996 report remained on what needed to be done to deal with unacceptably low productivity growth and an unacceptably unequal distribution of income.

Putting the best face on the first three years the Clinton administration’s economic policies, one could say that they talked a good game about reducing inequality through education. Their major achievement in helping low-wage workers was the expansion of the earned-income tax credit, and the Economic Report warned that efforts to cut that credit as part of the Republican balanced-budget plan were dangerously misguided. In the 1998 budget agreement, the Clinton administration could justifiably claim that it had succeeded in beating back those efforts. In fact, as the welfare reform bill began to be implemented during 1997, those former recipients entering the low-wage job market were able to benefit from expansions in the credit.35

However, the expansion of government infrastructure investment appears to have been mostly in the area of exhortation.

The Administration has promoted public sector investments in technology through programs such as the Advanced Technology Program and the Manufacturing Extension Partnerships (at the Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology) and the Technology Reinvestment Project (at the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research project Agency).36

Later in its report, the council warned against deficit reduction via reductions in public capital investments.

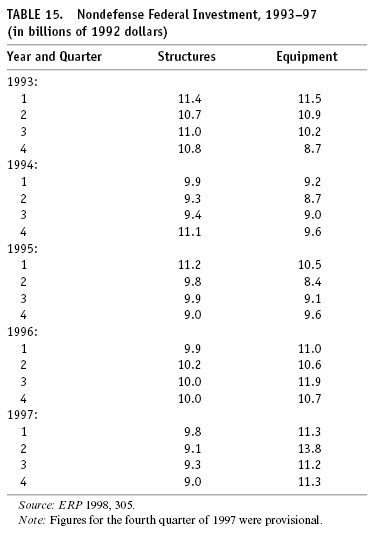

In a departure from the previous calculations of the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis beginning with the 1996 Economic Report, the proportion of government purchases of goods and services that could be classified as investments rather than current expenditures is estimated. These investments do not include the intangible investments in people (education and training) and technology but only the most obvious investments as measured by the building of structures and production of equipment. The quarterly data for federal nondefense equipment and structures is shown in table 15.

It appears that the Clinton administration was unable to reverse the decline in real spending on structures. Equipment spending did rise from its nadir in the second quarter of 1994 and surpassed the level of real spending that had occurred in the first quarter of 1993 during 1997. Comparing the percentage of all federal purchases spent on civilian equipment and structural investments in 1992 with the percentage in 1997, we see a slight decline from 1.65 percent to 1.45 percent.37 This is evidence that despite the rhetoric the Clinton administration had been unable to deliver on its promises to refocus government spending on investments. This is, of course, consistent with the information revealed by Woodward in The Agenda.

Completing the Volcker-Reagan Policy Change

Let us recall that even before Clinton became president he was forcefully told by his advisers and by the chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Alan Greenspan, that the key to his success was to “satisfy the bond market” if he was serious about cutting the budget deficit. Yet even with complete focus on reducing the deficit, the Clinton administration was still faced with Fed policy that slowed down the economy in 1994 because the rate of unemployment was getting dangerously low and the rate of growth appeared “unsustainable.” The result was that in 1995 the first two quarters saw a substantial slowdown in the rate of growth, to less than 0.5 percent. By contrast, the third quarter saw that rate jump to 2 percent.38 Though the Clinton administration concluded in its 1996 report that “evidence suggested that the economy was once again growing at its potential rate,”39 the evidence from capacity utilization and unemployment indicated a significant slowdown. Capacity utilization edged downward between January 1995 and the end of the year,40 while the unemployment rate moved between 5.7 percent and 5.5 percent between April and December.41

The slowdown was so pronounced that the Federal Reserve actually reduced the Federal Funds rate from April 1995 through the end of the year after having raised it from 2.96 percent in December 1993 to 6.05 percent.42 For 1996, the Fed adopted a wait-and-see attitude, taking action neither to ease the supply of credit nor to constrict it. In March of 1997, true to form, they raised short-term interest rates because the unemployment rate had remained below 5.5 percent since the previous July. Even though this did not succeed in slowing the economy, the Fed made no further restraining move for the rest of the year. However, they continuously indicated in public statements and leaked behind-the-scenes memoranda that they were very concerned that an unemployment rate below 5.5 percent was dangerously low, and that the rate of growth of the economy in excess of 2.5 percent was “unsustainable.”43

The Clinton Administration never challenged the Fed’s behavior nor the underlying view that a 2.5 percent growth rate was about as high as could be expected. Perhaps this was a more significant aspect of their policy posture than their effort to cut the deficit to appease the bond market early in their term.44 They followed the pattern that began with President Carter’s acceptance of Federal Reserve tight money in 1979 and 1980 and continued through President Reagan’s cooperation with the Fed during the 1981–82 recession and President Bush’s decision to leave to the Fed the entire burden of fighting the 1990 recession.

Active federal spending and taxing intervention to speed recovery from a recession is a thing of the past. The only role for fiscal policy, assuming supply-side tax-cutters don’t have their way in the near future, would be to cut the budget deficit down to zero. It is now up to the Federal Reserve to determine how low unemployment will be allowed to go and, when the inevitable recession comes, how quickly and strongly to apply stimulus to the economy. Gone are the days when John F. Kennedy was able (in 1963) to tout a tax cut as a method of accelerating a recovery from a recession or when Gerald Ford could push through a substantial tax cut (in 1975) in the midst of a recession in order to start the recovery.

Let us look more closely at this sea change in policy responses to recession as well as the divergent results of those different policies. Recall the comparison between the U.S. government’s response to the recession of 1974–75 and its policies since the 1990 recession.45 In 1975, the tax cut, which was passed in an effort to combat the recession, resulted in a big jump in the federal budget deficit. By contrast, there was no tax cut at all in response to the recession of 1990. Though the budget deficit rose because of reduced revenues and some automatic spending increases, there was not as significant a change in the 1990–92 period as there was in 1975 and 1976.46 In 1975, the year when the unemployment rate jumped to 8.5 percent, the percentage of the unemployed receiving unemployment compensation also increased from 50 percent to 76 percent. As the unemployment rate fell over the next two years, the percentage of the unemployed receiving those benefits also declined, averaging 56 percent for 1977.47 In 1991 and 1992, by contrast, even though the unemployment rate rose from 5.6 percent in 1990 to 7.5 percent in 1992, the percentage of the unemployed receiving unemployment compensation increased only from 37 percent to 52 percent before starting to fall.48

Even though the full responsibility of fighting the second recession was borne by the Federal Reserve System, it was much slower to push interest rates down in response to the 1990 recession than it was in response to the 1974 recession.49

The different responses to these recessions by the federal government and the Federal Reserve produced dramatically different results, some of which have been documented in this and the previous chapter. The unemployment rate fell from 1975 through 1979, while the economy grew dramatically for three years, 1976 to 1978. During those four years of recovery, close to 13 million jobs were created. Since 1990, as we have seen, the recovery has been very slow. The rate of growth was actually negative in 1991 and was so slow in 1992 that the unemployment rate rose in the first two years of the recovery. Between 1990 and the end of 1996, this sluggish economy had only created 9 million jobs.50

After peaking in 1975 at 12.3 percent the percentage of the population living in poverty fell through 1978 to 11.4 percent. During this period, the number of individuals receiving AFDC cash assistance fell from a peak of 11.3 million to 10.3 million. In 1990, the percentage of the population living in poverty was at 13.5, and it rose through 1993. The number of individuals receiving welfare rose from 11.5 million in 1990 to 13.6 million in 1995. These numbers mask the fact that the percentage of children living in poverty covered by that program stayed above 70 percent for the period 1975–78 but stayed at or near 60 percent for the period 1991–94.51 As we have mentioned, the response of Congress and the Clinton administration was to abolish this program entirely and leave the effort to fight poverty to the fifty states.

However, as we have also noted, the federal government and the Federal Reserve were not just sitting back and ignoring the economy. Far from it. In 1990, the Bush administration teamed up with the Democratic majority in Congress to push through a tax increase combined with spending controls in order to reduce the federal budget deficit. (The recession actually raised the deficit, as mentioned previously.) In 1993, the Clinton administration pushed through a major tax increase and controls on future spending. This time, these actions, combined with the quickening pace of recovery in 1992 and 1994, did lead to a fall in the federal deficit through 1997.52 The Federal Reserve was not to be outdone. We have already seen that when economic growth threatened to be “too high,” the Central Bank raised the Federal Funds rate from 2.96 percent in December 1993 to a peak of 6.05 percent in April 1995.53

The change in focus must be noted. Whereas economic policy in 1975 had been designed to increase the rate of growth, to reduce the level of unemployment, and to soften the blow of unemployment and poverty for those unable to find work and/or a decent level of income, after 1990 policymakers shifted focus to cutting the budget deficit and slowing the economy in order to prevent an inflation that hadn’t even begun.

The drumfire of complaints about the deficits from the 1980s, left unchallenged by the press as well as by many economists, had achieved this singular result. Half the arsenal of aggregate-demand management had been mothballed, the half controlled by elected representatives of the people. The Clinton administration came into office promising “People First” with A Vision of Change for America. Instead it has as its legacy an abject surrender to an unelected group of people who represent the financial sector of the economy. No amount of political mudslinging related to the budget battles of 1995 and 1996 and the presidential election of 1996 should be permitted to blind the citizenry to the “true revolution” in American economic policy. Paul Volcker’s and Ronald Reagan’s goals from 1979 and 1981 have been largely achieved. The federal government will shrink relative to the economy. The amount of redistribution of income to the poor will decline. Fighting inflation will be much more important than reducing unemployment. In the language of the radicals, a new social structure of accumulation is being built, one in which the capital-labor accord is nonexistent; the social safety net is restricted to the elderly; and the most important thing that governments can do with taxpayers’ money is to finance the defense department and a growing police and prison industry. This truly revolutionary transformation will continue as President Clinton and the Republicans “negotiate” the “reform” of Medicare and Social Security and poor women and children are left at the mercy of fifty parsimonious state legislatures.

So What Were They Fighting About?

We began this book with the victory of President Clinton and the reelection of the Republican majority in Congress. What apparently divided the Clinton administration from the Republican majority was the treatment of Medicare, the scope and nature of the tax cuts proposed, the changes in regulation, particularly environmental regulation, and the changes proposed in means-tested entitlements, particularly AFDC and Medicaid but also including the earned-income tax credit.

Yet President Clinton signed the “compromise” welfare reform bill before the election. After the election, the surprisingly rapid growth in the economy reduced the amount of spending cuts necessary, so the administration and Congress could put off the hard choices on how to reform Medicare. They even were able to restore some of the SSI benefits to legal immigrants that had been cut in the original bill. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that as the years go on, the trend toward fewer and fewer poor people receiving cash assistance will accelerate.

The euphoria of the strong economy at the end of 1997 and the beginning of 1998 led the Clinton Administration to propose a balanced budget for fiscal 1999, three years ahead of the schedule arrived at just six months previously. Nevertheless, the agreement made the previous summer still promises a series of spending cuts and tax decreases in the following years. These spending cuts will mostly be in the area of entitlement programs, particularly Medicare and Medicaid. However, as a result of welfare reform, there will also be limitations placed on expenditures for poor children under the state programs that replace AFDC, even though quantitatively that represents a tiny proportion of federal spending on entitlements.54 The one area where Clinton’s reelection has made a difference is in environmental regulation. A Republican president would probably have been more willing to acquiesce in the efforts by Congress to curtail regulatory activities in the cause of environmental protection.

As the Budget Deficit Shrinks to Zero, What Then?

When you add it all up, Clinton and Congress will continue the policy of fiscal restraint that was the hallmark of the first Clinton administration. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve will continue to threaten higher interest rates to keep a hint of inflation from entering the expectations of lenders and borrowers. These policies promise a rerun of the 1980s without the deficits to stimulate growth and employment.

As has been mentioned above, the key to the arguments in favor of balancing the budget is to be found in the crowding-out analysis. If there is 100 percent crowding out, so that every dollar of the federal deficit is a dollar that has not been invested by the private sector, then a balanced federal budget will unleash a great surge in private investment. Another important assumption associated with this view is that the private-sector investment that would replace the government spending is a better way for those dollars to be spent. When government spends the money, the result is bureaucracy and “socialism,” according to the rhetoric of, for example, former presidential candidate Senator Phil Gramm. When private investors spend the money, the result is private enterprise and “freedom”—and thus, obviously superior. Therefore, according to the supporters of budget balance by 2002, we should expect no decline in aggregate demand because the reduction in government spending will be completely offset by a rise in private investment. We also can expect more productivity growth because this private investment will be more productive than the government spending it replaces.

But can we really expect such a rise in private investment? Between 1993 and 1994, the rate of investment as a percentage of GDP rose from 13.4 percent (a very disappointing ratio considering the recovery that had been going on since 1991) to 14.5 percent, a very dramatic increase. Over the corresponding fiscal years, the federal budget deficit fell from 3.9 to 3.0 percent of GDP. This certainly appears to support the view that declining budget deficits will reduce interest rates sufficiently to stimulate more than enough investment to fill the gap. However, it is important to note that this occurred in the context of rising incomes and economic optimism. The deficit continued to fall to 2.3 percent of GDP over the next fiscal year, to 1.4 percent in fiscal 1996, and virtually disappeared by the end of 1997. Investment, however, rose only to 15.3 percent of GDP, a 1 percent increase in the face of a 3 percent fall in the deficit.55

This was in the context of Federal Reserve policy that saw the Federal Funds rate more than double from December 1993 through April 1995 despite the falling deficit/GDP ratio. Between April 1995 and the end of 1996, that rate fell less than 1 percent, even as the deficit/GDP ratio continued to fall.

With the budget at least temporarily in balance, private investment will have to rise another 2 percent of GDP to make up for the reduction in government spending’s stimulus to the economy. Such rises are not unheard of—in fact between 1983 and 1984, the percentage of GDP invested rose by a greater amount. But the record of the last forty years indicates that such increases in investment usually occur during a recovery from a recession. The most recent experience of significant reduction in the federal deficit as a percentage of GDP occurred between 1968 and 1969, when the federal budget went from a deficit of 2.9 percent of GDP to a surplus of 0.3 percent.56 Investment as a percentage of GDP went up less than one-half a percent, and the economy fell into recession in 1970.

The reasons this might be more likely to occur than the positive reaction anticipated by the proponents of a balanced budget are fairly straightforward. As in 1969, the economy at the end of 1997 was in outstanding shape. The economy posted the strongest rate of growth for the entire decade. The misery index was at its lowest point in over twenty-five years. Investment as a percentage of GDP was higher than it had been since before the recession. Yet this was an “old” recovery. The Asian financial crisis had already made investors very jittery, causing significant swings in the stock market since November 1977. In this context, investors are likely to be quite cautious about making long-term commitments, no matter what happens to long-term interest rates.

The experience of 1991 and 1992 supports this prediction. Beginning with the recession of 1990, the Federal Reserve Board pursued a policy of pushing interest rates down. Between June 1990 and January 1991, the Federal Funds rate fell from 8.29 percent to 6.91 percent. When the recovery proved extraordinarily sluggish, the Fed moved more vigorously and over the next two years cut the rate by over 50 percent (to 2.92 percent in December 1992). Meanwhile, the prime rate was 10 percent for most of 1990 and fell to 6 percent by August 1992, where it remained for over a year.57

Over the same period, the rate of growth in the GDP implicit price deflator fell from 4.4 percent in 1990 to 2.2 percent in 1993. Thus, the real Federal Funds rate fell during this period, while the real prime rate rose a bit. What was the impact on investment? Because of the sluggishness of the recovery from the 1990 recession, investment actually fell from 14.6 percent of GDP in 1990 to 12.2 percent of GDP before rising to 12.6 percent in 1992. True, the deficit as a percentage of GDP was rising, but the real burden of interest rates was not. We must recall once again that the only way a rising deficit can cause crowding out is by increasing interest rates, thereby choking off investment that would have occurred without the rise in the deficit.

What about the impact of the falling deficit? As the government budget moved toward balance by the end of 1997 without investment as a percentage of GDP rising sufficiently to fill the gap, why was there no recession in 1997? Consumption did not change much for the entire four-year period, remaining at approximately 68 percent of GDP. The trade deficit actually grew during this period so international demand for U.S. exports is not the source of the recent economic successes. The answer is that rising incomes raised tax revenues so much that government expenditures did not have to fall.58 The decline to aggregate demand when significant government spending cuts were anticipated just did not materialize.59 In addition, the rise in tax revenue did not decrease consumption because of the optimism of (mostly) high-income taxpayers whose increased capital gains, as a result of the stock market boom of 1996 and 1997, produced an unanticipated flow of revenue into the Treasury while giving them big increases in wealth as their stock portfolios all rose by over 30 percent. The problem with this scenario is the same with every stock market boom. When the bubble bursts, consumption will fall, and the failure to increase investment will be revealed as a major problem.

What If There Is a Recession?

As of January 1998, the Congressional Budget Office predicted a budget surplus by 2002 instead of a balanced budget as anticipated only five months previously. This prediction is based on an average growth of GDP of 2 percent a year in real terms. This average growth rate is quite conservative, being lower than the average for most comparable seven-year periods since 1960. In other words, the CBO is predicting that even if there is a recession during the period between the present and 2002, the low average predicted for the rate of growth of GDP should compensate for the temporary interruption in growth during the recession.60 There’s only one problem. When the recession hits (it is inconceivable that there will be no recession between now and 2002—that would create an eleven-year recovery, unprecedented in our history), revenues will drop and automatic spending increases will kick in. What will be the response of the president and Congress?

If they attempt to adhere to their programmed spending cuts, they will have to cut discretionary spending even more than planned to make up for the automatic increases in spending on unemployment compensation and the automatic decreases in receipts from income and payroll taxes. This will make the recession worse. However, such policy fortitude is unlikely. Even during the 1990 recession there was an extension voted in unemployment compensation by the Congress.61 No matter how minor the extensions, they added up to more money spent than was previously expected. Such increased expenditures coupled with declining revenues were the main reasons the budget deficit ballooned after the 1990 budget agreement supposedly adopted policy changes to reduce the deficit. By comparison, the 1993 budget was followed by declining deficits because the recovery from the 1990 recession proceeded apace and finally accelerated.

In the Economic Report of the President in 1996 and again in 1997 and 1998, the Clinton Council of Economic Advisers argued that there is nothing inevitable about the end of economic expansions. In all three reports, the council identified increases in the core rate of inflation (the rate of inflation with food and energy price changes netted out due to their volatility), financial instability either in the banking sector or among households, or a significant increase in inventories as potential killers of the expansion. Both reports argued that since there is no indication that any of these three factors will be problems in the near future, there is no reason to expect the expansion to end anytime soon.62 But of course that tells us nothing about what will happen after “soon” has passed. Perhaps the raging bull market that has caused Fed chairman Alan Greenspan to speak out more than once in warning will come crashing down sometime in 1998. Perhaps the Asian economic crisis will send a cold shiver of negative expectations over the business and financial community in the United States. Perhaps the Fed will not act swiftly enough to ease credit conditions in the United States in response to those expectations. After all, there are probably some inflation-hawks who still believe interest rates should have been raised in 1997 to cool the “over-exuberance” of the stock market. There are a whole host of factors that might trigger the next recession. What we can say with absolute certainty is that that recession will arrive well before 2002.

So what will Congress and the president do in late 1998 or 1999 or early 2000 after the recession hits? Will they support extended unemployment benefits? Will they increase block grants to the states whose welfare rolls will temporarily bulge with new clients? Will they increase block grants to the states for increased Medicaid expenditures? With unemployment rates rising and the increasing requirements that welfare recipients (even before they exhaust their family’s cap of five years) enter the workforce, will there be a special appropriation from Congress to create public-service jobs for these people? If Congress and the president take any of these rather obviously necessary actions in the face of a recession, they will be abandoning their path to deficit elimination by 2002. If they do not, the recession will be longer and deeper than the 1990–91 version, and that will also make a zero deficit by 2002 an impossibility.

The answer to this question brings us full circle to the question with which we began this book, “How does one make an economy better?” According to the conservative diagnosis, you reduce government spending to a minimum, you reduce taxes, particularly the marginal rate of taxation, and you reduce regulations. According to mainstream approaches, you practice aggregate-demand management, redistribute income appropriately, and attempt to stimulate economic growth with targeted tax cuts and expenditures. According to radical analyses, if the system does not fit together so that the incentive structure reinforces economic growth despite its inequities and instability, no amount of tinkering will produce acceptable results. The mainstream approach clearly ran out of gas in the 1970s, and we had a full decade of conservative changes in economic policy between late 1979 and the 1990 budget agreement. After a half-hearted effort to reverse some of the policies of the 1980s during 1993 and 1994, the government of the United States appears poised for another round of 1980s-style conservative reforms.

If our historical analysis of the Reagan-Volcker period is correct, the reforms promised by the Republican Congress and acquiesced in by the Clinton White House will not stimulate a dramatic increase in private investment and productivity growth. And because the targeted “investments” so celebrated in “Putting People First” and A Vision of Change for America have not been forthcoming and the Federal Reserve will probably permit unemployment to rise at least to 5.6 percent without taking action. The incomes of people at the bottom end of the income distribution will continue to stagnate; thus, inequality will continue to increase, further polarizing the middle class.63

Meanwhile, turning redistribution of income to the nonelderly poor over to state governments is a fait accompli. Neither does the administration appear interested in once again tackling comprehensive reform of the health care system. Thus, attempts to save money will continue to be ad hoc efforts aimed at reducing Medicare and Medicaid outlays without real reform. In other words, there will be some tinkering, but basic problems will be avoided as long as possible. Waiting in the wings are more radical plans to privatize Social Security and Medicare.

The “true revolution” in economic policy that began when Paul Volcker persuaded his colleagues to stamp hard on the monetary brakes in 1979 continued with the election and reelection of Ronald Reagan. The momentum of that revolution, reinforced by a drumfire of complaints about budget deficits, was so great it was able to turn back the tepid counterrevolutions of George Bush and the first two years of the Clinton administration, and the revolution is now complete. If history is any guide, the majority of people in the United States will benefit even less than they did during the Reagan era. At least then, the economy was driven forward by high budget deficits and put a lot of people to work. In a sadly ironic commentary on the poverty of economic policymakers, when the next recession hits, the only hope that the people will not be harmed even worse than in the 1980s is a return to “irresponsible” budget deficits to fight that recession.