IN a small room opening out of a ward in the Newhaven prison infirmary Trent sat facing Bryan Fairman, who lay back, enveloped in a dressing-gown, in a somewhat timeworn arm-chair. Trent had last seen his friend, and then for a few moments only, on the evening when he had so narrowly escaped missing the boat-train at Victoria. Fairman had then looked wildly excited as well as white and drawn with illness—in both respects unlike the austerely composed and vigorous personality known to Trent since student days in Paris. Today he appeared depressed and languid; his movements were listless and his voice, as he greeted his visitor, was apathetic. At the first glimpse of him Trent’s mind was made up as to the best means of broaching his business.

‘Look here, Bryan,’ he said lightly. ‘Before we speak of anything else, I want to give you a piece of news about yourself; good news too—at least I hope you’ll think so.’

Fairman’s brow contracted slightly. ‘Good news about me would be a nice change. I can’t guess what you mean.’

‘Don’t try,’ Trent advised him. ‘You wouldn’t succeed. The news is that old Dallow has repented in sackcloth and ashes. He says that it was all a mistake, and that he is sorry he made such a fool of himself, or words to that effect. He says that if you can get out of this jam you are in now, and go back to your job, and forget that there was ever any sundering of your loves, he will be devilish glad to see you again.’

The effect upon Fairman of these words was instant and transforming. His eyes opened and lit up, his cheeks flushed, his expression lost all its rigidity, a deep inspiration raised his chest and threw back his drooping shoulders. He sat up in his chair, his hands grasping the arms of it, and looked at his friend with all the well-remembered keenness. His voice had a new strength in it as he said, ‘I know you too well, Phil, to think you would tell me a thing like this unless you were sure of it. You understand what it means to me. Will you give me the details?’

Although Trent had counted upon something of the kind, the extent of the change in Fairman astonished him. Wasting no words on that, however, he proceeded at once to give, as fully as he could, the sense of what Verney had told him at their last interview. Fairman listened eagerly, and when the story was told he lay back in his chair and again drew a long breath.

‘Good Lord!’ he said, pressing his hands to his ribs. ‘This ought to wake up my metabolism properly, Phil. I believe I shall really be able to look lunch in the face for the first time in weeks. Now I will tell you something. There is another side to this business about Dallow, and you shall hear it presently; but first, what am I to do about escaping from what you so poetically call the jam I’m in? To begin with, there is a lot for you to explain—’

‘For me to explain?’ Trent exclaimed.

‘Yes, you. I feel interested at last, thank God! What you tell me has put a new heart in me.’

‘Stimulated the activity of the cardiac functions, I suppose you mean,’ Trent said reproachfully. ‘And you accuse me of using lyrical expressions. A new heart! Why, you ought to be kicked out of the Royal College of Surgeons, his Majesty having no further use for your services. Well, I will explain as much as you like when I know what needs explaining.’

Fairman smiled a tight-lipped smile. ‘That’s all right. First of all, then, I wish you would answer one or two plain questions. Had you anything to do with the murder of Randolph—anything at all, even indirectly?’

‘Absolutely nothing whatever, Bryan. Will that do for you? But what put this notion in your head? Not thrice your branching limes have blown since I beheld that person dead; but why the devil should you imagine I had anything to do with it? Never shake thy gory locks at me, old man; thou canst not say I did it. I mean, can you? Or do you? Or did you?’

‘I can’t say you did it,’ Fairman answered gravely. ‘I know you didn’t do it, if you tell me so. But you remember you wrote to me about Randolph making himself a nuisance to Eunice Faviell, and said you were going to see him, and you knew how to put a stop to it. When I saw him lying dead that came back to me. Still, if I had been in my proper senses at the time I shouldn’t have imagined you had actually shot him. But the important question is, Phil, does anyone else think you did it?’

Trent stared at him for some seconds. ‘Do you remember,’ he inquired at length, ‘what the Frenchman said when St Peter told him he could enter into heaven? He said, “Je vous entends la bouche bée.” That is how I feel now. Does anybody think I did it? Who do you mean?’

‘I mean the police,’ Fairman said quietly.

Again Trent stared at him, and his face flushed. ‘Oh! the police,’ he said slowly. ‘Does this mean, Bryan, that you know something that—but no; that’s impossible, of course. Still, you must have had some sort of reason for imagining that I might be suspected?’

‘That you might be—yes, I had. And it seemed a good reason to me.’

‘Well, it didn’t work, that’s all,’ Trent said. ‘And I will tell you why. I did call on Randolph that evening, at six; but I was let in by his manservant, Raught, and let out again by him about a quarter-past. I told the police so myself, without waiting to be asked; and Raught told them the same, before I saw them. Another point is that the surgeon put the earliest time that Randolph could have been shot as seven o’clock, whereas by 6:30 I was in the Cactus Club with Major Robert Sellick Patmore, D.S.O. He didn’t get rid of me until it was time for me to drive to Victoria, where I ostentatiously bought some flowers, saw someone off by the 8:20, and watched you just failing to miss it. Ten minutes later I was helping to start the Oastlers’ housewarming party in Bloomfield Terrace, and stayed there until midnight. So there you are. Philip Trent, the well-known prison-visitor, left the Court without a stain on his character, amid deafening cheers which the magistrate made no attempt to suppress.’

‘My reason was a good one, all the same,’ Fairman said. ‘You’ll say so when I tell you what it was. But if you are not suspected, there is one other question. Is someone else—someone we both know?’

‘You are making my brain reel,’ Trent complained. ‘I wish you wouldn’t; I hate the feeling. No, and no, and no; in other words, the answer is in the negative. As far as I can say, the only person who has been suspected up to now, my dear friend, is your mysterious self—also for a very good reason, written in your own hand, and posted to Scotland Yard.’

‘Ah!’ Fairman said. ‘So you know about that. It is part of the story, of course.’

‘I guessed that it might be.’

‘Well,’ Fairman said, ‘now the ground is cleared of all that, I will tell the story, and you can let me know what you make of it.

‘It begins on the morning of the day Randolph was shot, when I got a note from Dallow—my chief, you know—telling me, without any beating about the bush, that he was not satisfied with my work and that I was discharged with a half-year’s salary. Of course, you don’t know Dallow. I wasn’t astounded so much at his putting it like that, curtly and without preliminary. Dallow is like that. If he had caught any of the staff doing something discreditable, or if he was satisfied a man was slacking on the job, he would sack him in just that way. What did amaze me was his treating me in that style. It wasn’t only that I knew there was absolutely nothing against me—he had often said nice things about my work, in fact, and I knew it was sound work myself. But Dallow, you see, has always been a scrupulously fair man, and a good fellow generally in his dry way—though for all I personally cared he could have been what sort of man he liked so long as he was the very great alienist that he undoubtedly is.

‘So I was completely taken aback at hearing this from him. Still, I assumed there had been some mistake, which could easily be cleared up in a personal interview. But not a bit of it. When I saw him, he simply stuck to it that I had got to go, and that there was no more to be said; and when I realized that there wasn’t, in fact, any more to be said, I simply went to pieces. As you know, Phil, I was in no condition at that time for standing a shock. I had had ’flu badly on top of months of overwork, and I had known well enough I was due for a serious break-down if I couldn’t get away for a rest. Dallow himself had told me I would have to, only the week before, and had urged me to knock off. I would have done it, if I hadn’t been at the critical stage of a controlled experiment—the sort of thing you can’t wash out and start all over again.

‘I don’t remember much of what I said to Dallow when it became clear that it was a settled thing, and I had got to go; but I know it was not polite. Then I went back to my quarters and—you are the only man I would tell this to, Phil—I shed tears for the first time since I was a little boy. You don’t know what acute nervous fatigue is. It is bad enough when you haven’t really got anything to worry about; when you are merely at the end of your strength. Even in that condition you can get the feeling, a purely causeless feeling, that life is not only not worth living, but unbearable. It’s the state in which many a man has done away with himself without any ostensible reason whatever. But when you get, on the top of that, the abrupt removal of the only thing that was keeping you more or less balanced—well, that is the end. Or so it seems to you. When I left Dallow I felt that it was impossible to go on living; and at the same time I felt, with the last relics of sense I had left, a horror of the idea of suicide—of the painful and repulsive sort of circumstances that go with suicide.

‘But it’s no use, I know, trying to explain to you what my sensations were. They were completely morbid, and if you haven’t had them yourself you can’t possibly understand. I will just go on to tell you what came into my mind as I sat there having the horrors. I thought of my old friend Raoul d’Astalys, that I used to share rooms with when we were both students at the Salpétrière. I don’t think you met him.’

Trent, who knew the time allowed to him for his visit to Fairman to be limited, had already decided to waste none of it in describing his fruitless journey to Dieppe. He therefore said, ‘I have met him, though. The Comte d’Astalys—a tall fellow with large, melancholy eyes.’

‘That’s the man. He was not the ordinary student by any means. I don’t believe anyone else knew as much as I did about the work he was doing, and especially about his study of euthanasia. He had the idea, you see, that a time was coming when getting rid of life by agreeable means would be a legally recognized thing; not a crime at all, but a part of the regular apparatus of civilization. Now I knew that d’Astalys had kept up his researches. The last time I had been in touch with him, a few years ago, he had read a paper on Eastern methods of analgesia, at the Académie de Médecine, that started a big discussion. I had written to him then, and he had replied from an address in Dieppe—he said in his letter it was a house that had belonged to his family for generations, but was now officially known by the good republican name of 7A, Impasse de la Chimère. I gathered that he was not very deeply attached to the Republic. The Impasse de la Chimère! That is,’ Fairman said with conviction, ‘a God-forsaken spot if there ever was one.’

‘Is it?’ Trent inquired innocently.

‘Yes—but never mind that. I was going to say that, some time after getting his letter, I happened to hear some vague gossip about a scandal in which d’Astalys was mixed up; something that had been kept very dark by the authorities. I heard it from a French doctor who had come over to see what we were doing at the hospital. It was a story about orgies of drug addicts being held at a place in Dieppe with the queer name of the Pavillon de l’Ecstase, which belonged to d’Astalys. I didn’t really believe, when I heard it, that d’Astalys would ever have had anything to do with that sort of thing; but when the blow fell on me as I have told you, it was enough for me that there was even a chance of d’Astalys having become an unscrupulous character. I knew he approved of euthanasia in principle, and I hoped now that he would not mind breaking the law. I resolved then and there that I would look him up, and get out of him some means of putting myself away comfortably and happily, and so as to look as if I hadn’t done it on purpose. I felt sure he could do that, and I hoped he would do it, if I undertook to keep him out of it. But I didn’t really think about any snags there might be; I just wanted to get going, to be doing something, and I routed out my passport and began packing a bag at once.

‘It was while I was doing so that I had another idea. It struck me suddenly that this sacking me was almost certainly not Dallow’s work at all, but Randolph’s. More than once he had made it pretty clear that he had taken a dislike to me; I couldn’t imagine why, and I didn’t bother, because it never occurred to me he would go the length of ruining my life just for a whim. But now, the more I considered it the more sure I became that this must be the explanation, whatever Dallow’s reason might have been for lending himself to such an outrage.

‘I went down at once to the telephone and got through to Brinton Lodge. They told me Randolph was in London, and gave me the address. I thought, all the better; I’m going through London anyhow. I determined to see if I could find him, and make an appeal to him—I didn’t care what I did if only I could get back to my work. I say, Phil, I’d like a cigarette if you’ve got one. They’ll let me smoke in here.’

Trent gave him what he wanted, standing over him while he gratefully drew the smoke into his lungs. ‘Poor old Bryan!’ he said, laying a hand on the other’s shoulder. ‘What an awful time you have been through! I suppose it’s all right for you to go on yarning away like this. As a doctor, I mean, you know what suits you.’

‘Do me good!’ Fairman said. ‘I have had a long rest; and if I know anything about psychology, letting loose all this that I’ve had bottled up inside me is the very thing for my complaint. Besides, what I have heard from you this morning has undone the worst of the knots I was tied up in. You don’t know!’ He reached up and pressed for a moment the hand on his shoulder as he resumed his tale.

After obtaining Randolph’s address (he said) he took the next train to London, arriving there with nearly an hour to pass before the departure of the boat-train from Victoria. From Euston he took a cab to Newbury Place. He was feeling exhausted and ill, but he was determined to go on with the program he had vaguely mapped out for himself. He rang once; then, hearing no sound in the little house, rang again. Still nobody came, and he stepped out from the doorway to look at the upper floor. He could see that there was a light in the upper front room. The window was thickly curtained, but there was a thin pencil of light where the curtains had not been drawn together completely. While ringing a third time, he happened to place his hand on the door, and found to his surprise that it was not latched.

He pushed it open, stepped into the lighted passage, and called out asking if anyone was at home. There was no answer; and Fairman, who in his state of mental disturbance cared for nothing but his purpose of coming face to face with Randolph, put down his bag and began hastily to search the place. The rooms on the ground floor were in darkness, and he proceeded to mount the stairs. Turning to the left, he came to the open door of a brightly lighted room, and the first glance within showed him the dead body of the man he sought lying where he had fallen.

Fairman hurried into the bedroom. As a doctor, he needed no more than a moment’s examination to make sure that Randolph was past all help, and he left the body undisturbed. The shock of surprise had for the moment a steadying effect, and the plain fact that murder had been done produced its natural reaction of horrified interest. His attention was attracted at once by a litter of papers, wrappings and string on the floor before the open safe, and he went over to look more closely at what lay scattered there.

At this point in his story Fairman was checked by an exclamation from Trent.

‘Papers! Do you mean written papers, Bryan—written or printed; not only brown-paper wrappings?’

‘Yes; a number of small packets of papers—seven of them, to be precise—I counted afterwards. Each packet was secured with an elastic band. I could see at once that the outside sheet of each packet was headed by a name in large letters, with lines of close, neat writing underneath it. There was also a thick budget of manuscript in a parchment cover.’

‘Documents! This is getting interesting, Bryan; because the police—I happen to know this—didn’t find anything of that sort.’

‘No,’ Fairman said. ‘Like you, I happen to know they didn’t find anything of that sort; because nothing of that sort happened to be there when they looked. I will tell you how it was.’

Fairman had bent down to look more closely at the papers on the floor (he said) and immediately his eye was caught by a name on one of the packets. It was the name DALLOW.

Fairman took the packet in his hand. It was thin and light, consisting apparently of a few letters on ordinary note-paper—as was the case, he found afterwards, with most of the packets. He looked then at the writing on the covering sheet, which was in Randolph’s characteristic hand; and as soon as he had read the first paragraph he understood very well the nature of the compulsion under which Dr Dallow had been brought to act as he had done that morning.

‘I am not going to tell you what it was,’ Fairman said. ‘You wouldn’t, Phil, if you were in my place. All I need say is that it was something which meant utter ruin for Dallow if ever it was disclosed. I might add, too, that it was something he had done, very probably, out of kindness of heart. It’s only fair to him to say so.

‘Well, there I stood for a minute or two, taking in this discovery. It didn’t make me feel any happier; it made no difference to my position, that I could see. Randolph had done his worst for me. Someone else that he had had under his thumb, I imagine, had paid him back with a bullet, and had gone off with the papers relating to himself. But as for me, I was no better off; and the wave of unbearable depression came over me again as I stood there. I was sweating at the palms, my ears were singing, and my feet felt as if I was shod with cotton wool. One thing occurred to me to do. I looked rapidly over the notes written on the other packets. They were quite evidently all of the same character. Although none of the names was known to me, I decided to do those unfortunates the kindness of destroying the evidence of their indiscretions in the past; and I stowed away the lot of them, including Dallow’s, in my coat pockets.

‘And then, Phil, I looked at the first page of the bundle of manuscript. Can you imagine what I found it to be? You can’t, of course; yet it was the text of a book you have told me about more than once. It was that thing of Wetherill’s.’

‘What!’ Trent exclaimed. ‘Do you mean The Broken Wing? And he had it in that safe—of course, that is just where it would be. And what happened to that, Bryan? Did you take it? The police didn’t find it.’

Fairman nodded with a lowering face. ‘I took it—yes. Stole it, if you like, for that at least was Randolph’s legitimate property, I suppose, though how he came by it I cannot think. Or perhaps he had borrowed it from the repulsive brute who wrote it. I didn’t care. I only knew I wasn’t going to leave that infamous thing lying about for anyone else to see. So I put it under my arm and carried it off; and at the present moment it is at the bottom of the Channel, tied up in a bundle along with the other papers.’

‘Good!’ Trent said with keen satisfaction. ‘And what then, Bryan?’

‘Why then, handling those packets of letters, as most of them were, I was reminded of something. I thought I would send a farewell note to yourself, Phil, as my best friend, saying a few of the things that one leaves unspoken as a rule, before I took the final step. I meant to write it in the boat-train. I had pen and pencil on me, stamps in my note-case; but I had no paper. There was none to be seen in the bedroom, and I hurried downstairs thinking I would forage for some in the living-room before I left the place.’

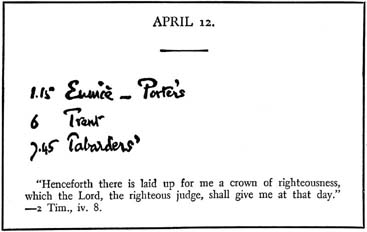

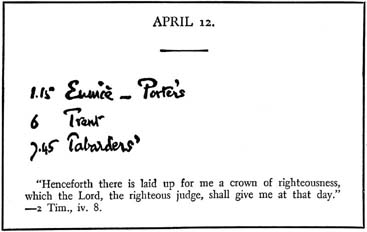

Fairman had entered the front room on the ground floor, and switched on the lights. He saw the writing-table at once, and upon it the open-fronted cabinet with its ample choice of what he was seeking. He helped himself to a number of sheets of blank paper and some envelopes; and as he was doing so, his eye was caught by the names written on the visible leaf of the engagement-block that stood on the top of the cabinet. He gazed in bewilderment at the neatly pencilled record that would speak so plainly to those looking for light on the matter of Randolph’s death.

‘1:15, Eunice, Porter’s,’ he read. ‘6, Trent.’ And at the bottom of the page, ‘7:45, Tabarders’,’ followed by a printed sentence from one of the Epistles.

The name of Eunice in this context was quite unmeaning to Fairman. The mere name was a stab to his sensibilities; and for an instant he wondered hazily how this note of an appointment with Randolph could be reconciled with what he had heard of her resentment at the old man’s attempts to win her favour. But, what fixed his attention was the name of his friend, put down for a visit that had preceded by little more than an hour his own unappointed appearance on the scene of a fatal crime.

‘You can see for yourself, Phil,’ Fairman said, ‘how it might look to anyone in a state of mental incoherence. Muzzy as I was, I simply wasn’t capable of thinking straight. The nearest I could get to putting my ideas together was something like this: “Here is Randolph shot dead—Phil was here with Randolph only a short time ago—Phil came here intending to have a row with Randolph—Phil may be suspected, whether he did it or not.” And at that point, you see, I had my brilliant inspiration.’

Trent looked fixedly at his friend. ‘Yes,’ he said slowly. ‘I begin to see.’

‘If I was going to make an end of myself, as I very certainly meant to do in any case, here was the chance of doing it to some purpose. You have saved my life, which is the sort of thing a man doesn’t forget—’

‘A man might try,’ Trent said impatiently. ‘Anyone who happens to be a good swimmer is not a hero because he rescues someone who isn’t; if he didn’t, he ought to be drowned himself. I would have done the same for anybody; you know that.’

Fairman laughed gently. ‘Yes, I know that. But it happened to be me, through no fault of yours, and it is one of those little trifles that stick in one’s memory, as I was saying. And so, when I saw your name written there, inviting the attention of anyone looking into the matter of Randolph’s murder, my mind was made up in a moment. Then I just did the first things that came into my head. I tore off the leaf from the block and stuck it in my pocket. I went out into the passage and ripped the label with my name on it off the bag, and chucked it into a corner. Then, just as I was going, I thought about fingerprints; so I went upstairs again to the bedroom, where I had noticed the water-bottle and glass, and took a drink.

‘After that I cleared out as quick as I could, and hailed a taxi in Bullingdon Street. I had been much longer at Randolph’s than I had ever anticipated, and I had only just time to book a passage and catch the train—as you saw. That was another little jolt for me.’ Fairman closed his eyes with a reminiscent smile. ‘There you were, as cool as Christmas, and evidently with not the least idea of fleeing the country—in fact, looking a little bit bored, I thought—and there was I, flustered and feverish and right at the end of my tether, feeling far worse than I should have done if I had shot the old man myself.’

After this brief glimpse of his friend, Fairman said, he had taken his seat at the table in the Pullman and begun to consider what he should do. He had already settled it with himself that he would leave behind him a letter to the police stating that he was guilty of the murder of Randolph. Deciding on the form of the letter was not so easy. He began and then abandoned first one, then another; in the end he came to see that the more of detail he put into the story, the more chance there was of its being discredited by some small, unrealized error. The final letter satisfied him as being the barest possible form that could be given to his false confession; and he had posted it at the station office at Newhaven.

One disconcerting thing had happened during the change from the train to the steamer at Newhaven. Without his perceiving it, the leaf torn from Randolph’s engagement-block had dropped from among his papers to the floor of the carriage; and it had been picked up by an old lady, who afterwards tried to restore it to him. Confused at first, he had quickly reflected that there was nothing on the leaf that could tell a story, and had simply denied all knowledge of it. In mid-Channel he had watched his opportunity to go to the side of the vessel, unseen, and drop overboard the parcel he had made of the documents taken from Randolph’s bedroom.

Arriving at Dieppe about two in the morning, he took a room at a hotel, and passed a few hours in drug-induced, yet broken, sleep. He then rose, and asked to be directed to the Impasse de la Chimère. After several times renewing his inquiries, he came at length to that remote neighbourhood. There was no mistaking the house when he came to it—a typical château—but it was, to all appearance, deserted. Repeatedly he rang the bell at the somewhat dilapidated outer gateway without result, and no sign of habitation was to be seen about the house itself. The smaller house whose grounds adjoined those of the d’Astalys mansion, and which bore the name of which he had heard—Pavillon de l’Ecstase—was silent and deserted too.

Worn out and distraught as he was, Fairman had not failed to notice that he was being curiously observed from the windows of the large, old-fashioned inn that occupied the end of the Impasse. This was evidently the place to yield information about the whereabouts of the people of the big house; and thither Fairman now betook himself, ordering coffee and brandy to be served to him in the room looking out on the quiet street. But he found there was nothing to be learned at the Hôtel du Petit Univers. The huge man who kept the place avoided his eye when questioned, and mumbled that he had enough to occupy him without keeping watch on the comings and goings of his neighbours—if the comte was not at home, that was none of his, the innkeeper’s business; nor did he know of any other address at which the comte might be found.

After such a reception, Fairman had not energy enough for any further pursuit of his attempt to regain touch with the Comte d’Astalys. Weary, sick, and engulfed in the blackest despair of the soul, he had dragged his footsteps back to the harbour and booked a passage by the one o’clock boat back to Newhaven. ‘It was,’ he said to Trent, ‘the only thing I could think of. I meant to destroy myself; and by that time I was too far gone to think of anything the least little bit out of the way. Do you know what I mean? I mean that I had crossed over by sea, and naturally I had thought about drowning when I looked into the water, and when I threw those papers overboard; and now, after failing in the crazy business I had set out on, I came back to that, and never thought of anything else.

‘And what happened afterwards I expect you know. I did try to jump overboard, when I thought nobody was paying the slightest attention to me; and the first move I made, a large and powerful man, whom I had been watching scratching his head over a crossword puzzle, was on me like a cat on a mouse. If I hadn’t been such a wreck as I was,’ Fairman added regretfully, ‘I would have given him a lesson against interfering with other people’s private business.’

‘You didn’t do so badly, at that,’ Trent assured him. ‘I am told that Sergeant Hewitt’s appearance has been simply ruined for the time being.’

‘Oh, well!’ Fairman said. ‘If I did anything of that sort, I’m sorry. I didn’t really mean what I said about giving him a lesson—it’s the sort of thing one says without thinking. Of course I soon found that he was a police officer, doing his infernal duty; but at the time when he tackled me, I would have torn his heart out with all the pleasure in the world.’

‘Never mind,’ Trent said. ‘I don’t suppose Sergeant Hewitt minds. The sort of marks you gave him don’t last long, and the sort he has got added to his record for pinching you will do him plenty of good. And so you were run in as a suicide; and then, according to what I hear, you crumbled into ruins. Now, look here, Bryan; we have got to think about the best way of getting you let loose again. The only thing for you to do if you will take my advice, is that whenever anybody asks you, you give the whole story, without any reservation whatever—including your reason for stacking it all up against yourself.’

‘All right,’ Fairman said. ‘I was thinking I would do that in any case. If you are out of it, there’s no point in keeping my mouth shut any longer. But they won’t believe me. There is a good enough case against me.’

‘Though you say it as shouldn’t, eh? Well, never mind about that; it may not be as good as you think. You haven’t been tried for murder yet, you know, and if you ever are, it may not be in the precise form that you expect. You know what they are holding you for at present, of course.’

‘Of course. Suicide.’

‘So I thought; but I am told that the official way of putting it is rather more ornamental. A captious critic might even call it laboured. The way the law looks at it is that when you tried to jump overboard, you did it with intent then feloniously, wilfully, and of your malice of aforethought, to kill and murder yourself. It is possible that that is the only murder charge you will have to meet, and I don’t think it should worry you. When you are taken to court again, which will be quite soon, the evidence as to your state of health, both before and after the rash act that didn’t come off, should be quite enough. What will happen—so I am told—is that if you consent to be dealt with summarily, you will be bound over to come up for judgment when called upon; which will be never, if you behave yourself. And now I must leave you, Bryan, before they throw me out. The next time I see you, I hope and believe, you will be at liberty again—at liberty to dine with me, in the first place.’

Trent got up to go, then checked himself. ‘Oh, I forgot one thing,’ he said. ‘You have heard me mention my aunt, Miss Yates, haven’t you? I had a letter from her this morning, to say she is returning soon from Rome, where she has been making a short stay with friends. She describes an odd experience she had on the way there, between London and Dieppe.’

Fairman looked a little mystified. ‘Well?’ he said.

‘She enclosed a little document which she thought would interest me. I thought it would interest you.’ He drew from his letter-case a slip of thin paper, which he handed to his friend—a printed leaf, with a few words of handwriting upon it as follows:

At Scotland Yard a few hours later, Inspector Bligh succeeded, after several attempts, in getting speech by telephone with Trent at his house. His words were brief and guarded. ‘I’ve got your letter,’ he said, ‘and I believe you have got hold of the right end of the stick. As for what you propose, I’m willing to try it. But we can’t talk about these things over the wire. How soon can you see me here?’

‘In about half an hour.’

‘Right. Come along.’

‘There’s one thing,’ Trent said, ‘that I didn’t mention in my letter. You might think it over while I am on my way. Those fingerprints on the razor-blade—you haven’t traced them, have you?’

‘No.’

‘I thought not. They were mine.’ And Trent hung up the receiver.