How Dysregulated Eaters Become “Normal” Eaters

(It’s about Self-care, Not Just Health Care!)

■Helping dysregulated eaters have a better relationship with food and improved body image

■How poor self-care, irrational beliefs, mixed feelings, and inadequate life skills underlie dysregulated eating

■Guidelines for “normal” eating

■The difference between “normal” and nutritious eating

Hopefully, by now, you’re starting to understand that dysregulated eaters have underlying challenges that affect their eating, self-care, and health. Later in this chapter, we will tell you how to help them improve their relationship with food and their bodies and become “normal” eaters, but, for now, it’s important to learn a bit more about the dysregulated eaters you see in your practice. There is much more to know than meets the eye.

How can you recognize which of your patients are dysregulated eaters? Obviously, some of them may raise their eating or health concerns when they first meet you. Or you may meet a patient and, because of his or her large size, bring up the subjects of eating and exercise. Other patients may have a low or average weight, yet have dysregulated eating that you are unaware of. They may be caught up in the diet-binge cycle and simply believe that’s how they’ll live out their whole lives. They may be average size or slim, but eat in a way that does not contribute to health or longevity. Or they may “watch their weight” so closely that, though obsessed by food and weight, they never allow themselves to gain a pound. These are all forms of dysregulated eating.

Just as you can’t judge a book by its cover, you can’t assess health by looking at someone’s size or weight. It may surprise you to learn that many patients who are highly successful, functional, and well put together live in daily distress over food. They’re so ashamed of their eating behaviors that they wouldn’t dare tell you about them. They figure that if they look good from the outside, no one will ever know how badly they’re doing (with food and life) on the inside.

One approach is to ask patients how their relationship with food is. If you notice blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglyceride numbers which are not within a healthy range, feel free to ask with a neutral, not a condemnatory, tone, “How do you feel about your eating?” or “What’s your relationship with food like?” and wait to see what answer you receive. Another avenue is to build a nonjudgmental, caring relationship with them so that they begin to trust you enough to see that you want to help them. Make no assumptions, use active listening skills, ask open-ended questions, and look for conversational openings when they may make references to any kind of eating concerns. Remember, the more together patients appear, the harder it may be for them to disclose eating difficulties.

I’M NO SHRINK, SO ONCE I IDENTIFY DYSREGULATED EATERS IN MY PRACTICE, HOW DO I HELP THEM IMPROVE THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH FOOD AND THEIR BODIES?

In graduate school, it is pounded into the heads of social work students to view the client in context and to think in psychosocial terms. Their view is the panorama of a client’s life, going deeply into their histories and spreading outward into the present. It is also recommended for doctors treating patients with eating and weight concerns to take this broader view as well.1

From the psychosocial viewpoint, every factor is fair game when assessing what is happening with a client. Using this perspective, it is useful to consider: (1) how clients take care of themselves in general (which is based, in large part, on how their parents or caretakers took care of them), (2) what they believe about food, eating, weight, and appearance as well as the core beliefs they live by that generate self-esteem and self-worth (which develop from what their culture and family believed and how they were treated), (3) how well or poorly they manage life (which skills were or weren’t modeled and taught by family and gained through outside experiences), and (4) how they are able to resolve any mixed feelings about eating and weight issues (also derived from family and culture).

In this chapter, we’ll explore and address some of the more subtle and often invisible but powerful ways that psychosocial factors affect the patients we meet in our medical offices every day. First, we’ll look at what could cause people to develop an unhealthy relationship with food and their bodies; then we’ll explain what “normal” and nutritious eating are, how they differ, and ways in which you can guide dysregulated eaters to have a sane, healthy relationship with food and their bodies.

Please don’t take it personally and get angry at your patients for failing to do what they said they’d do: start that walking program they swore they’d begin last year or follow the food plan their diabetes educator gave them. However poorly your patient is doing, it’s the best he or she can do at that moment. Remember, hard as it may be to accept, we all are doing the best we can in any given moment based on our histories, circumstances, and internal resources—even though how or what we’re doing may not be good enough. Accepting this axiom may seem contrary to common sense because it makes us feel as if we’re letting folks off the hook and not keeping them accountable, as if we’re saying it’s okay that they’re taking the easy way out. But that’s not what we’re saying or doing, and the principle makes complete sense when you carefully think it through.

For example, say you run a race as fast as you can, beating all your previous records and most of your competitors, but still come in last. You are doing the best you can, but it’s not good enough to win or place in the race. If a therapist follows every clinical guideline to save a client from committing suicide and the client does it anyway, the therapist has done the best he could, but it wasn’t enough to prevent a client’s death by his own hand. If a surgeon performs a successful kidney transplant, but the patient develops a rejection reaction, the surgeon has done the best she could, but it was still not good enough to ensure an optimal outcome.

The idea is that we all are functioning at our highest level every moment of our lives based on factors too numerous and complex to discuss here. For many people—and many patients—their best is woefully deficient and inadequate. Not everyone’s best is good or even approaches mediocre. Some of us will do better than others simply by virtue of the fact that we all don’t start off on a level playing field. The bright note in this sobering admission is that people can learn new skills and do often improve, so that their best becomes better and eventually good enough.

So, let’s assume that your patients with eating and weight concerns are doing the best they can around food, which currently might be poorly. With help, terrible self-care may rise to middling, and fair self-care may rise to good. It’s no use being angry at patients for taking poor or even downright awful care of themselves—eating a constant diet of high-sugar and highly processed foods, being a total couch potato, not taking their medicine, failing to follow through on the testing you repeatedly and urgently recommend with the noblest of intentions. Most can—and will—improve with the right guidance. What they often need are some learnable self-care and life skills.

Here are some ideas to consider when patients are not doing as well at improving their health as you and they had hoped.

Self-care

There are numerous reasons that people don’t take good care of themselves consistently. Some had substandard role models in their parents or grew up in conditions of poverty, wretchedness, or crime-ridden neighborhoods in which food was scarce and self-care was narrowly defined as not getting yourself killed. Maybe your patients’ families had no health insurance or had distressing or disastrous experiences at hospitals or neighborhood clinics. Many of your patients—no matter how self-assured and accomplished they may appear!—may have been mistreated emotionally, sexually, or physically as children and, deep down, don’t believe they deserve to take care of their bodies or their minds. If your patients grew up lounging in front of the TV snarfing down Doritos or canned spaghetti for dinner every night while their parents were minding their other children, out working, or even in another room getting drunk, they never may have actually been well cared for and may be clueless as adults about what caring for oneself physically or emotionally entails.

Patients may have had their eating in childhood inappropriately micro-managed or neglected entirely. They may have been of “normal weight” but their parents feared them getting fat (because it ran in the family) and supervised every morsel that went into their children’s mouths. Some were raised in families where emotions were aired too publicly and uncontrollably or where feelings were never expressed, so that they never learned effective emotional management skills, which puts them at high risk for emotional eating. It is vitally important not to make any assumptions about patients’ eating because they seem to be living the good life. Often it’s these patients, whose lives look so good on the outside, who feel like a mess on the inside and end up struggling with food.

In order to take good care of ourselves, we need to have had caretakers who more often than not adequately met our mental, emotional, and physical needs, so we could then internalize doing this for ourselves. We cannot stress strongly enough that many people—many of your patients—have poor self-care because they were never taught to care for themselves. For many, being poorly cared for left them (perhaps unconsciously) believing they weren’t worth the trouble; hence, they don’t value themselves enough to take the trouble now. Even for those who were well cared for in childhood, repeated cycles of restrictive dieting, deprivation, and “failure” to attain a comfortable weight may have undermined these patients’ positive body image, self-efficacy, and feelings of self-worth, leaving them fluctuating between self-care and “I don’t care.”

Sadly, they may view your efforts in caring for them as a waste of time or themselves as a lost cause. Though it might be hard to believe, you may be the first person in a very long time who has taken a real interest in how they are faring in this area. Therefore, it may take a while for your caring to sink in.

Treating patients who have internalized worthlessness can be a one-step-forward-and-two-steps-backward affair. You finally get them to monitor their diabetes daily and they slack off taking walks with the “Sunday morning walkers” club they joined. Or you manage to call in a favor to slip them into a stress management group, and out they drop after two sessions. Sometimes, the best thing you can do is to help them find a therapist who will move them toward resolving their underlying conflicts about their own self-worth, or a health and wellness coach who can help them improve their self-efficacy and develop a plan to reach their personal wellness vision one step at a time.

It will help you and your patients succeed in supporting their self-worth if you make it a point to “Reframe the task [at hand] from weight loss to self-care. People with a healthy sense of self-worth consistently and conscientious take care of their own health. Positive changes in thinking and behavior are fundamental to all psychotherapy treatments, but a sense of self-worth, which is a perceived and felt sense of self, cannot be meaningfully altered with CBT [Cognitive-Behavior Therapy] alone. When people perceive themselves as attractive or unattractive, intelligent or unintelligent, or adequate or inadequate, they live accordingly. Perception of self is experienced as reality and a negative self-perception robs many overweight patients of the faith in self to do what it takes to be healthy.”2

Therapists and wellness coaches appreciate that lasting behavioral change is built upon a solid foundation of nonjudgmental awareness, consistent self-compassion and self-acceptance, and a well-defined wellness vision rooted in a person’s individual values, plus a deliberate commitment to consistent, ongoing self-care. For patients, taking ownership of their own self-worth and taking the time to consider exactly what they want for themselves from a wellness standpoint can be empowering. This “internal locus of control” for wellness-related behaviors is what helps patients stay motivated and consistent with their healthful eating or activity regimen when outside forces interfere.

The fact is that “ego damage is harm to one’s sense of self-worth, and many overweight patients come from ego-damaging families in which they developed a sense of inadequacy. Many learned to put the needs of others ahead of their own, leaving little time to attend to their own health. Their subsequent weight gain is then perceived as confirmation of their inadequacy.”3 Without appreciating that they might use food and overeating to try to care for themselves when they do not otherwise feel deserving of their own attention, patients may not recognize their troublesome eating behavior as part of their efforts to address an unmet need or manage feelings of inadequacy. They may feel trapped in a vicious, exhausting cycle. Because of this, experts recommend that in addressing eating and weight concerns, “We need treatments that include strategies to repair ego damage, enhance the sense of self-worth, and develop self-efficacy so that overweight patients can become the agents of change in their pursuit of well-being.”4 Such strategies are best found within an interdisciplinary model of patient care, which we discuss in later chapters.

In your professional interactions, you can model self-compassion by telling patients, “It seems like you’ve got a lot going on in your life, especially taking care of other people. I hope you’re taking time for yourself.” Or smile and say, “You know you are allowed to take care of yourself. You deserve it.” The goal is to help patients believe that they are deserving of self-care and a healthy life regardless of their size. Once they believe that wholeheartedly, empowering self-talk and positive behavioral changes will likely follow more automatically.

Brain food for providers: What is the benefit of viewing patients’ eating and weight struggles as self-care problems? Do you understand that the key to making permanent lifestyle changes is helping to increase feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy in a patient?

Brain food for patients: Do you have problems taking effective, ongoing care of your health? What did you learn about taking care of yourself growing up? Are you willing to focus on improving your total self-care as an actual goal rather than simply trying to lose weight?

If what you’ve been doing with patients who have eating and weight concerns—focusing only on changing behavior—hasn’t worked, it’s time to try something different. Although we have machine-like parts of our bodies such as lungs, heart, and joints, we also have brains which are far less mechanistic. Beyond neurotransmitters and hormones, neural pathways and synapses, at the core of being sentient animals, we have a set of conscious or unconscious beliefs upon which our feelings and behaviors are predicated (whether we realize it or not).

In particular, we have cognitions regarding the value of certain foods, the activity of eating, weight ideals, and the importance of appearance. Beyond that, we have beliefs about what we deserve in life and our ability to achieve it. Isolating patients’ behaviors from their beliefs and feelings about the above may be tempting, but it won’t help you help them. Psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, who pioneered Cognitive Therapy, now better known as Cognitive Behavior Therapy or CBT, was on to something when he began doing testing on how to conceptualize depression and had the realization that depressed patients’ negative thoughts were the foundation of their depressive behaviors.5 Dysregulated eaters, who are often chronic dieters, hold a slew of (conscious and unconscious) irrational, unhealthy beliefs about how their bodies got to where they are today and whether they can make them different tomorrow. Here are just a sampling of the beliefs they may possess which underlie their behaviors:

Beliefs about food: Foods are either good or bad, Food is the enemy, Food is love and comfort, I need to be in tight control of myself at all times around food, I am bad if I waste food, I should eat only nutritious foods, Food is the perfect reward, I can’t trust myself around food, Eating “good” food makes me a good person and eating “bad” food makes me a bad person, If I had a better relationship with food, my life would be perfect, There is something defective about me that I can’t have a sane relationship with food no matter how hard I try, Food is my best friend.

Beliefs about eating: I must finish all the food that’s put in front of me, I better eat a lot now because tomorrow I may put myself on a diet, Eating is better than feeling emotional pain or discomfort, Eating is so psychologically painful that I wish I didn’t need to do it, Hunger is scary, Eating fills the emptiness inside me, Eating is a great stress reliever, Feeling good or bad about myself is dependent on the foods I eat or avoid eating, I am being deprived if I can’t eat whatever, whenever, or as much as I want, I’ll never be any good at feeding myself, Other people eat what they want, so why can’t I? I’m entitled to eat when I have had a hard day, Eating fills time and solves the problem of boredom, Eating is self-care, If I make or buy food, I must eat it all, I must only eat high-nutrient-density food, I must always eat from hunger and never for pleasure, Eating someone’s food is a way to show I love them, Eating is better than feeling hurt.

Beliefs about weight, body size, or appearance: I must be thin or thinner to be lovable, I am fat and disgusting looking, People hate fat folks, Thin equals success and happiness, I should weigh myself every day if I want to be a comfortable weight, Weighing myself is the scariest part of my day, I’m a failure if I can’t lose weight and keep it off, I don’t trust my body to know what or how much it wants to eat, My fat body is something to be ashamed of, I love myself when I’m thin but not when I’m fat, My body will never look like I want it to, I hate my body no matter what size it is, Fat is ugly and thin is beautiful, It doesn’t matter what positive attributes I have if I’m fat because no one will pay attention to them.

Imagine a prediabetic thirty-five-year-old female patient we’ll call Liddy who is 5’1” and weighs 186 pounds, with a long history of dieting and regaining weight sitting across from you in your office. Let’s say Liddy believes that food is the perfect reward and comfort after a stressful day, she’s being unfairly deprived if she says no to the high-fat/high-calorie foods she enjoys, and she shouldn’t need to lose weight for people to love her unconditionally. Now, we’re not implying that these are rational beliefs, just that they are Liddy’s and that she—like many people with unconscious beliefs—has no idea that they are holding her back from attaining health and happiness.

According to these beliefs, if you, her doctor or health care provider, tell her that she needs to lose weight, she’s going to interpret that as you telling her she’s not good enough or lovable enough as she is. Should you tell her to cut back on highly processed foods, she’s going to feel deprived and unable to cope with her stressful day. What we have is you talking about her becoming healthier and her hearing only that she’s not okay as she is and that life is about to become even more grim if she gives up her comfort and stress-relieving yummy food treats.

Now let’s imagine another patient. At sixty-seven years, Al is 5’8”, weighs close to 350 pounds (much of which he carries in his belly), and has had one knee replacement and suffered one heart attack. Al believes that it’s a sin to waste food and not get your hard-earned money’s worth, especially when he and his wife go out to dinner; eating is better than feeling emotional pain or discomfort; and no one has the right to tell him what he can eat and how much he should weigh because that’s his business. While you’re trying to help Al avoid another knee replacement and a second heart attack, he’s thinking that you’re crazy to advise him to waste uneaten food that he’s paid good money for, you want him to be in emotional pain, and you’re trying to control him by butting into his personal business.

This confusing dynamic, this common kind of miscommunication, this case of you not understanding where your patients are coming from and them being clueless that you’re out to help, not harm, them, is frustrating and disheartening on both sides of the exam table. We’re giving you extremes of beliefs about food, eating, and weight here, and we grant that not every patient presents with these kinds of irrational belief systems. Many more likely believe that they can take weight off but not keep it off; restricting food is a struggle that they don’t want to do for the rest of their lives in any way, shape, or form; it’s not fair that they have to stop eating foods they love when other people can eat them and not get fat; taking away food is taking away life’s fun and pleasure; and the deprivation they’re going to feel by giving up foods they love will make them so miserable, they’ll be driven to, well, eat. These beliefs are not unusual, even among successful, high-achieving people, and patients do not need to present with a high BMI or weight in order to have them. Sadly, these beliefs are as common as a winter cold.

When you make suggestions or give advice to patients about what they can do to become healthier, ask permission first, and then make sure to check out their facial and body reactions. Do they fold their arms in front of their chest and nod pleasantly? Do they tense up or look away? It’s fine to ask, “May I make an observation?” Or “I’m happy to make suggestions, but you know what’s best for yourself, so don’t feel you need to do something just because I think it might be a good idea,” encouraging them to think for themselves and act wisely on their own behalf.

The above are only the beliefs that patients have about food, eating, and weight. In addition, they have what are called core beliefs, which form the foundation of their lives and dictate everything they say and do. Here are some core beliefs your patients may feel that may complicate the picture: I need to be perfect at eating or exercising or not even bother trying; I’m not a worthwhile person and don’t deserve pleasure, health, or happiness; Life is a struggle, and eating well and exercising will be a struggle too; No one can tell me how to eat or what to do; People are always trying to manipulate or control me; I can’t depend on anyone, so why bother to get support for eating better; I can’t take care of my body, so why try; Everyone in my family dies young, so I probably will too; I’m a failure and a loser because my family always told me so, I never finish doing anything, so why bother starting; I’m not sure I’m worth taking care of; I need to live small, not take risks, not rock the boat.

We don’t mean to make you feel helpless or despairing. On the contrary, we only want you to recognize that patients are brimming with unhealthy beliefs that can lead to what looks like self-sabotage or lack of concern for their health. When it comes to promoting lasting health behavior improvement, these are what you are up against as much as any medical conditions with which patients enter your office.

To learn more about rational and irrational eating, food, weight, and core beliefs, we refer you to The Rules of “Normal” Eating by Karen R. Koenig.

Brain food for providers: Are you aware or surprised that your patients have some or, more likely, many of the above beliefs? Does recognizing this help you understand why they struggle to make progress or attain consistency with resolving their eating and weight concerns?

Brain food for patients: Are you aware of having the beliefs listed above? Can you see how having them makes it difficult for you to change your eating habits? What steps will you take to make your beliefs more rational and healthy?

HOW IS IT THAT PATIENTS CAN APPEAR SO GUNG HO AND EVEN DESPERATE TO IMPROVE THEIR EATING AND HEALTH, THEN TURN AROUND AND DO NEXT TO NOTHING TO HELP THEMSELVES?

Mixed feelings

It often does seem truly mind-blowing how patients seem to have split personalities—hungering for better health, yet not doing a darned thing to achieve it. However, this pattern isn’t indicative of mental illness, but of mental conflict: when patients say they want one thing and then go off and do the opposite, this is symptomatic of plain old, garden variety ambivalence. Other names for it are mixed, conflicting, opposing, or contradictory feelings. We want something and also want its opposite or, said in more psychological terms, we may desire and also fear something. And, sad to say, without psychology intervening, humans are hard-wired for fear to trump desire every time.

To understand the power of mixed feelings, let’s look at examples of internal or intrapsychic conflicts outside the eating and weight arena. You want to plan a trip to visit your elderly parents because that is what a “good” son or daughter does, but your relationship with them is so strained that you always leave them vowing never to return. Or, you’ve been in practice for over forty years and feel burned out and tired of the same old grind, but also worry that if you retire, you won’t know what to do with all your free time or be satisfied living with a steeply reduced income. Or, you wonder if you’re overdoing it when you down a couple of glasses of wine at home after work, but don’t wish to give them up because nothing else seems to decrease your stress so magically.

Get it? You want this and also you want that. Psychologically speaking, when our intent does not align with our actions, something is going on and we call that dynamic internal conflict. Most of us have mixed feelings about a great many things. This dynamic is pulling the strings when we waffle, procrastinate, or do something that benefits us for a while, then stop doing it. Sometimes we’re aware of having these tugs within and sometimes we’re not. Almost always, avoiding doing something we insist we want to do is a tell-tale sign that we have an internal conflict brewing. Our lives are filled with minor and major sets of ambivalent thoughts, and the best we can do is try to resolve as many as we can.

Now back to the subject of food and weight. Think about why patients might be ambivalent about giving up eating certain foods or having a particular identity (say, fat) that they’ve had their entire life. Consider how patients of high weight might want to do both: get fit, but dread going to the gym in form-fitting, flashy workout clothes; give up the pint of ice cream they share with their spouse while watching their favorite TV shows at night, yet feel upset about losing this intimate, cherished ritual; quit making a stop at McDonald’s after work every day, but not know how else to de-stress and reward themselves before going home to take care of an invalid parent. Remember that, irrational creatures that we all are, many (if not most) of our decisions are made by our emotions and often without conscious deliberation.

There are a number of intrapsychic, generally unconscious conflicts that patients with eating problems often have that may derail them from attaining or sustaining their eating and weight goals.6 “In fact, the internal struggle between the patient’s desire to be healthy and her lack of faith in herself to do what it takes is reflected in the well-documented pattern of short-term weight loss followed by relapse that is independent of treatment models.”7 Although weight gain is often due to the body’s metabolic reaction to restriction from dieting, sometimes it also reflects the ambivalence patients feel about giving up comfort foods or living in a smaller body.

■Conflicts about trying and failing (again and again)

Let’s face it, you are probably not the first health care provider who has suggested or alluded to your patient eating more healthfully. Chances are good that many patients have been working on or avoiding working on (but still obsessing about) their relationship with food and weight for a long time, maybe even since childhood. That they don’t eat healthfully or that they weigh more than they might prefer is not news to them. It is pretty much a post-it on their brains every minute of every day. Moreover, it’s more than likely that they have dieted and even lost a substantial amount of weight one or more times.

Gallup polling reveals that “trying to lose weight is something most Americans can identify with. Two-thirds say they have made a serious effort to lose weight at least once in their life, including 25% saying they tried once or twice, 30% trying between three and 10 times, and 8% trying more than 10 times. Nearly three-quarters of women (73%) have ever attempted weight loss, with an average of seven attempts. By contrast, just over half of men (55%) have ever tried to lose weight, with the average trying fewer than four times.”8

Unfortunately, the patient you see before you doesn’t view herself as a success in shedding pounds (no matter how many she’s shed and how often she’s shed them), but as a failure for not keeping them shed. She is terrified of getting her hopes up about keeping her weight down and often fears disappointing others (again), depriving herself of foods she loves (again), obsessing about what she can and can’t eat (again), dropping several dress sizes (again), and losing any number of pounds only to see the entire process reverse itself (again).

So, really, can you blame her for being a mite ambivalent upon embarking on the whole endeavor yet one more time? While you’re focused on how she’s going to become healthier, she’s fixated on ending up exactly where she is now, with one more failure under her belt, and wondering why she should bother wasting her time and considerable effort. At best, she’s ambivalent; at worst, she feels despairing and helpless.

■Conflicts about giving up food for comfort and pleasure

Imagine if suddenly all your comforts were taken away—no more TV or iPhone, Pinterest, hobbies, Barcalounger, get-away cabin in the mountains, friends, or pet Pug. You would undoubtedly feel utterly lost and bereft. Even if having every one of these things had an obvious downside (though we can’t think of any for a Barcalounger), you would still feel their loss because of the sheer enjoyment they bring you.

Now imagine if one of the major pleasures—no, make that the only pleasure—in your life was food, glorious food. Or if you believed that eating was the glue that kept your life together because food made sure you were never bored or lonely, sad or anxious. Remove the glue and you imagine your whole life falling apart. That is what it is like for many dysregulated eaters when they imagine giving up the foods they love (or even eating them in smaller quantities than they’re used to). Sure they want to be healthier and slimmer, but it’s difficult for them to reconcile these lofty goals at the expense of suffering such perceived catastrophic loss.

Hyperbole, you might think. Not really. This is what your patients are feeling. This is what the authors of this book felt when we thought of giving up food for comfort and pleasure. Emotional eaters fervently wish to believe that they can eat normally—after all other people seem to have acquired the knack—but are terrified nonetheless. And this is what produces their conflicting feelings: wanting more than anything in their lives to give up using food for comfort and pleasure and just as strongly living in terror of giving it up.

■Conflicts about deserving health, happiness, and feeling positive about themselves

We are all encouraged when people tell us that they wish to be healthy and enjoy a happy life. We are fooled because many of the people who say this are fooling themselves due to not recognizing the truth. They think they want all these things (who wouldn’t?), but deep down don’t feel deserving of them. Not all of us had joyful childhoods where our parents loved us unconditionally and wanted the best for us so that we internalized their love and caring and now love and care well for ourselves.

True, some people who were abused or neglected get out there and try to prove their parents wrong by succeeding, most often through overachieving. Some of them may even end up ratcheting up their self-esteem so that they no longer need to prove anything to anyone. But others were put down so many times that they carry deep within them the conviction that there is something terribly, irrevocably wrong with them, that they are defective, and that they don’t deserve either a good life or the best in life.

If patients are conflicted about self-worth, how can they achieve success and, often the more difficult task of maintaining it? Sometimes they do succeed: they eat better and exercise regularly and their triglyceride levels and LDL plummet, they lower their hemoglobin A1C and start to get their diabetes under control, and maybe even enjoy the thrill of running a 5K race with friends or family. These accomplishments spring from the part of themselves that wishes to believe that they’re worthy, so they allow themselves the gift of success.

But then doubt creeps in, triggered by the discomfort of unfamiliarity about feeling deserving. “I’m fooling everyone, including myself. Soon people will see right through me and know that I’m a fraud and that I don’t deserve all these good feelings and kind words.” And so begins the abrupt or gradual descent into perceived undeservedness and the thoughts of “Gee, I guess Mom was right and I won’t amount to anything. I’m too lazy to even cook a decent dinner for myself” or “Dad always said I can’t stick to anything and who am I to prove him wrong. Look at me, I haven’t been for a run in weeks. My career may be in great shape, but my eating habits are a mess.”

Many high achievers, raised in families in which there was tremendous overt as well as subtle pressure to succeed, do so, but they still feel as if they don’t deserve it. The name of this phenomenon is “The Imposter Syndrome,” a term first coined by Suzanne Imes, Ph.D., and Pauline Rose Clance, Ph.D., in the 1970s. Also called intellectual self-doubt, this phenomenon, which makes it difficult or even impossible to accept success or achievement, including weight loss and “normal” eating, is “generally accompanied by anxiety, and, often depression. It is one of the causes of the internal dissonance that some people who’ve lost weight feel and one of the reasons the weight comes back on.”9

Thus the yo-yo dynamic, the revolving door, the arduous climb to the top of the mountain and the awful, shocking, rapid slide back down. Most of your patients may have no idea they feel undeserving or even uncomfortable with their success, but their patterns belie their pretense of worthiness and happiness, whether they know it or not.

■Conflicts about emotional and sexual intimacy

Intimacy is generally portrayed and thought of as a heavenly, blissful state: we trust, open our hearts, expose our authenticity, surrender to vulnerability, lean on others, and ecstatically merge with another human being. But that’s only the upside of closeness. The downside is the fear that most of us have experienced: of lost intimacy through physical or emotional abandonment (intentional or accidental), betrayal, or rejection; of our vulnerability being manipulated or used against us; of our emotional supports being stripped away and of falling flat on our faces; or of isolation and perpetual loneliness. It should surprise no one that we are frightened of intimacy because it holds within it the seeds of its loss.

What does intimacy have to do with eating and weight? Plenty. Odd as it may sound, some patients may use their size as a barrier to intimacy. It can (if they let it) reduce the number of people who: will ask them out, wish to have intimate physical relations with them, and take the time to unwrap the cocoon in which they’ve swathed themselves. This isn’t because they are not wonderful people worthy of love or intimacy. It’s just the way our fat-phobic, thin-obsessed society operates and the way that people with body image issues, particularly those at the higher end of the weight spectrum, often perceive themselves.

Love and intimacy are always a double-edged sword. Being large can function like the keep out sign on a teenager’s door, especially in the arena of sexuality. Let’s face it, sex means physical closeness and maybe even emotional closeness. It’s both a metaphoric and real undressing and laying bare of oneself.

Moreover, many people of higher weight report feeling more comfortable with their sexuality when they’re thinner. Some fear that they will act on those feelings. With intensified sexual feelings and being hit on more often due to conforming to cultural attractiveness standards comes the possibility of cheating in a monogamous relationship or being super-sexually active (what is judgmentally called promiscuous) as a single person. This is frightening to some people, men and women alike. So, sometimes to not act on their erotic impulses or not act on them as they did the last time they slimmed down, they end up putting the weight back on, which allows them to rationalize a return to a more comfortable asexual status quo.

■Conflicts about being controlled by others

You easily may be able to distinguish someone caring about you from someone trying to control you, but, we assure you, to many people, they feel like one and the same. It all depends on your upbringing. If your parents were my-way-or-the-highway kind of folks and schooling was rigid and built on top-down dictums, you may be sick and tired of being told what to do. When parents are domineering and demanding and children have little or no say in most matters, they can build up a serious head of steam about being told what to do—or worse, being lectured, badgered, bossed around, and punished for doing what they want. What may emerge is someone who will fight against being told what to do and will go out of his or her way to ignore or do the opposite of what is expected—even when it’s clearly not in their best interest.

We know it sounds irrational that patients would rebel against what’s best for them, but this is what happens—too often, unfortunately. There you are expressing your wish that a patient become a little more active because you actually like him and want him to live long and prosper. And he’s hearing you as yet one more person who believes he can’t think for or take care of himself, one more lecturer about what he should do and needs to do, one more authority figure out to control his life. A related conflict is that people may fear that successful behavior change in the present will increase their vulnerability to criticism if success in childhood was met with criticism from others (perhaps by a competitive parent or sibling). In this way, success becomes both a hoped-for and dreaded occurrence.

Clinically, what’s happening here is that the patient is taking an old, interpersonal problem and re-enacting it in the present, making you the hated authority figure, a dynamic psychology calls transference. Another dynamic that occurs is that patients internalize an old interpersonal conflict and it becomes a current intrapsychic one: when their inner voice is urging them to broil a nice piece of fish rather than eat packaged fried filets for dinner or not to finish the bag of cookies they’re devouring while watching TV, they feel bullied and refuse do it.

These are strange dynamics, to be sure, re-enacting old interpersonal battles around food, exercise, and self-care when the battlefield is one’s psyche. They sound like this: “Go to the gym and you’ll feel better,” challenged by “I know I should but I don’t feel like it.” Or “You know that if you bring that bag of malted milk balls home, you’re going to eat them all,” challenged by “So what, I’ll eat them if I want to.” Or “You’ll feel better tomorrow if you go to bed rather than stay up and eat ice cream,” challenged by “I’m sick of being told what to do. I’m entitled to eat whatever I want.”

When you sense that a patient wants to do something—start biking more, buy a treadmill, cut down on eating out at restaurants, or buy more nutritious foods—but that he or she is having difficulty taking action, you can always say something like “It’s not unusual to have forces that make you want to move forward in taking care of yourself and forces that want to hold you back. Like many people, you may have mixed feelings about all you feel you need to do to get healthier.”

To learn about more conflicts that your patients might have around food and weight, read Karen R. Koenig’s Starting Monday—Seven Keys to a Permanent, Positive Relationship with Food. It’s all about these conflicts and how to resolve them.

Brain food for providers: After reading about internal conflicts, do you have a deeper comprehension of why your patients seem to sabotage their own best efforts, taking one step forward, two steps back? How does recognizing these conflicts give you more compassion for your patients? How might you help them recognize and resolve these mixed feelings?

Brain food for patients: Do you have any of the above conflicts? Which ones are the greatest barriers to resolving your food and weight concerns? Do you feel more compassion for yourself now that you understand that what looks like self-sabotage in the health and wellness arena is often a symptom of an internal conflict? Who could you speak with about them to get full resolution?

WHAT MAKES IT SO HARD FOR SOME CLIENTS TO MANAGE THEIR LIVES MORE THOUGHTFULLY AND HEALTHFULLY?

Life skills

In order to succeed at anything, we can’t depend on sheer luck, hope, or prayers. We need skills. The abilities we require to live fully functional lives as adults are called life skills and are defined by the World Health Organization as “abilities for adaptive and positive behavior that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life.”10 Life skills fall under categories like taking care of your health, managing stress and emotions, living purposefully and in balance, handling relationships, and problem solving and critical thinking.11

Life skills are not unlike occupational skills in that they provide us with tools to get a job done well. Sadly, however, we have no such curriculum, practice arena or exam for life skills. We simply toss people into the sea of life and they either sink or swim. Moreover, we can’t assume that because people have excellent occupational or social skills, that they also possess top-notch life skills. When patients with eating and weight concerns come to see you, you might make assumptions about their life skills based on their occupational skills—she’s a high-powered attorney, he’s a prosperous real estate mogul, she successfully raised four great kids single-handedly, or he received an award for Principal of the Year. Think of the exceptional people you know in your field who are respected and honored, but who live in a state of perpetual struggle and dissatisfaction because they lack life skills or what you might even call “common sense.”

Effective life skills don’t suddenly and magically develop on their own, but need to be taught and practiced. If our role models modeled and taught us effective life skills, how fortunate we were. If what we saw and learned was mediocre, well, maybe we make do and, if we’re lucky, pick up what we missed along the way. But what if our role models had very little functionality and what we came away with in the life skills department was bupkis? What then? How do we cope with life? There are a number of life skill areas in which patients often have deficits which impact their ability to eat well and exercise consistently. Recognizing what they’re missing will help you be more compassionate toward them and help you guide them toward support services.

■Physical self-care

This skill can be compromised if, as discussed earlier, we are not competently cared for by our parents or if they didn’t model proper self-care for us. You can’t expect a patient who never was served fresh vegetables to start craving them because health guidelines now say that they’re good for him or her. Or one who was given take-out or frozen dinners every night in childhood to suddenly know how to or enjoy cooking. Moreover, eating well is not just about what patients feed themselves but also about why they eat. If they had parents who used food for comfort (“I know I shouldn’t have a second piece of cake, but I’m so lonely since your father left us”) and diversion (“There’s nothing on TV, so, hey, kids, let’s go for ice cream”), they will need to recognize and change these habitual patterns in order to take better care of their health.

Physical self-care isn’t only about food and exercise, however. It’s about patients viewing their bodies as precious objects and taking commensurate care of them. Patients first need to learn why they would wish to value their bodies and only then how to do it through healthy and “normal” eating and physical activity. Remember that this is unchartered territory for many patients, so be careful not to make the assumption that they want or know how to care for their bodies. Many don’t have a clue.

Consider that “emotional eating is considered a risk factor for eating disorders and an important contributor to obesity and its associated health problems. Linear regression analyses found that proneness to boredom and difficulties in emotion regulation simultaneously predicted inappropriate eating behavior, including eating in response to boredom, other negative emotions, and external cues.”12 Managing emotions is perhaps the major life skill that dysregulated eaters lack. They don’t know how to prevent stress from building up, make choices which avoid or lessen it, or what to do when they experience too much of it. Moreover, some patients, through temperament or upbringing (or both), see most of life as stressful. Whereas some folks might view changing jobs as challenging or exciting, other patients view it as worrisome and terrifying. Whereas some might think that living alone is freeing because they’re beholden to no one, others may find it scary and overwhelming to take care of all the major and minor details of life themselves.

Moreover, many patients, particularly those who are depressed, find it mega-angst provoking to go grocery shopping or cook meals for themselves or others. For various reasons, they are uncomfortable with what they perceive as too much responsibility for themselves; rather, they’re desperate for people to take care of them. Explaining to someone which aisles to avoid in the supermarket or how to read a label is pointless if all the time he or she is thinking, “I hate grocery shopping almost as much as I hate cooking. It’s too stressful. I can’t do it. It’s too much work.”

Some patients lead lives that are brimming with stress from childrearing, taking caring of elderly parents, and demanding jobs. Unfortunately, brainstorming with them about how to reduce stress in their lives actually may cause them more agita because they fear they’ll fail at what you suggest. Eating is cheap, quick, and easy as a relaxant compared to finding or paying a baby sitter in order to go to the gym or take a meditation class. Eating feels less taxing than taking a walk during a lunch break or when energy is flagging mid-afternoon. People who are easily stressed or who have (intentionally or unconsciously) set up their lives to be stress filled want instant relief and are not thinking about what they’re doing to their bodies with food other than chilling them out momentarily.

Managing emotions is another sad affair. Brené Brown, social work professor at the University of Houston, popular TED talk presenter, and best-selling author of Daring Greatly and The Gifts of Imperfection, “asked hundreds of people to list all the emotions that you understand in yourself. The average number was three: happy, sad and pissed off. We don’t have a full emotional lexicon.”13 Unfortunately, many of us are more familiar with emoticons than with actual real-life emotions. If patients can’t identify what they feel, how in the world will they know what will make them feel better (other than food, of course)?

When we do think of feelings, too often we feel fear and confusion. We think that emotions are pesky annoyances, trying to drag us down or bum us out. We have no use or time for them: the heck with feelings, we need to get on with the action of life. This is the attitude that Western culture has taught us about our emotional lives, so it’s not surprising that many patients are out of touch with feelings and have no earthly idea of what to do with discomfiting ones. It seems to them like a no-brainer: experience internal distress (never mind identifying exactly what the emotion is) or grab some cookies. Duh! Importantly, some people feel that if they are experiencing negative emotions or difficult feelings, or if a situation is difficult or suboptimal, that they must be doing something wrong. How freeing (or terrifying) it is when they learn and accept that imperfection is an expected, normal part of a life well-lived!

Unless patients become more skilled at preventing and managing stress and identifying, experiencing, and handling intense or difficult feelings effectively, no amount of nutrition counseling is going to stop them from emotional eating. After all, food-seeking is a biological imperative. Emotional management, not so much. Knowing what you’re feeling and what to do with whatever emotions come up can make all the difference between mindless emotional eating as an ineffective attempt to self-soothe and healthy stress management behaviors. “As predicted [in a NIH study], emotional awareness moderated the link between urgency and binge eating.”14 In his book, Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman, Ph.D., explains that “emotions that simmer beneath the threshold of awareness can have a powerful impact on how we perceive and react, even though we have no idea they are at work.”15 Goleman cites research by Leon et al., indicating that “emotional deficits—particularly a failure to tell distressing feelings from one another and to control them—were found to be key among the factors leading to eating disorders.”16

Feel free to tell patients that they might want to consider an alternate approach if they’ve been trying to eat better by using willpower alone. Then explain that they, instead, might need to enhance their life skills because none of us were born or brought up to have all the skills we need to manage life well. Make it okay to have challenging life skill areas. Tell patients, “You know, we learn so many skills in school, or when we’re new to a sport, but sometimes the hardest skills to learn are the ones we were never taught: how to balance work and play or take care of our emotions.”

■Self-regulation

We are not automatic regulating machines like our thermostats which flip on or off and up or down a smidge as needed. We need to regulate ourselves, and not just with eating, but this is often easier said than done. Unfortunately, most, if not all, dysregulated eaters have similar “What’s enough?” problems in other areas of their lives: work, play, parenting, sleep, spending, stress, etc. In order to self-regulate effectively, patients need to be in touch with what they are feeling, not only with food but also by sensing sufficiency and adequacy.

If they grew up in families in which their feelings were ignored or invalidated (which many dysregulated eaters did), they may well be unable to register and recognize body signals for when to start or stop eating. Instead, they go from one extreme (dieting) to the other (bingeing or overeating), ignore both hunger and satiation signals, and swing from spending hours at the gym to whiling away hours in front of the TV or computer.

Self-regulation, which is rooted in sensing emotional and physical signals, is key to “normal” eating (which will be discussed later in this chapter). In fact, without this skill, “normal” eating cannot and will not occur. “Behavioral theory suggests that treatments that increase participants’ use of self-regulatory skills and/or their feelings of ability (self-efficacy) will improve exercise and nutrition behaviors. Despite limited evidence, higher autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, and self-regulation skills emerged as the best predictors of beneficial weight and physical activity outcomes.” Moreover, “There was evidence of carry-over, or generalization, of both self-regulation and self-efficacy changes from an exercise context to an eating context.”17

■Critical thinking, goal setting, and problem solving

Ask many folks what critical thinking is, and they may well be uncertain and say, “Always telling people what’s wrong with them.” Critical thinking is not exactly a household term, but it should be. If we are not taught how to think clearly and rationally in childhood and don’t learn how in school, where would we develop this must-have capacity to discern what works and what doesn’t?

The fact is that many patients lead with their feelings, let their hearts overrule their heads, and don’t consider follow through, consequences, or cause and effect. The most important decisions of their lives are made this way—who they marry, how they vote, and the way they raise their children. If they don’t think rationally about these choices, how can you expect them to apply rationality to eating or exercise? Who among us hasn’t heard folks say, “Oh, I don’t go to the doctor (or the hospital or the dentist). I hate going there.” As if whether we like or dislike something is the sole arbiter for doing it or not.

As to goal setting, many patients either weren’t taught how to set and reach goals, had no one to model this process for them, or had such pressure to achieve, improve, and win at all costs that they might be afraid to move forward; or they’re tired of striving all the time and now simply want to sit back and watch life go by. They even may feel that their major goal is to have no goals. Either way, health care professionals would do well not to assume that their patients know how to set doable, realistic, concrete, chunked down goals and stay motivated enough to reach them incrementally.

One caveat on goals is that many patients who’ve struggled with food and the scale are super wary about setting eating and exercise goals because they see the process as a sure-fire way to fail. If patients don’t want to set eating or weight goals, please do not push behavioral goals until they are more ready for change. This means they will need to acknowledge, identify, and resolve whatever internal, likely unconscious, mixed feelings they have about success (see above conflicts). Mainly, they just don’t want to fail again, and are better off identifying and evaluating their beliefs, thoughts, and feelings about their circumstances rather than establishing quantitative objectives or target dates. Moreover, they may say yes to goals because they think that’s what you want to hear, rather than goals springing from what they wish to do. They want to feel that success is possible, but after multiple failures, they can’t help but look to their experience which laughs in the face of their hopes and dreams.

Regarding problem solving, many patients will agree that they’d like to develop better eating and activity habits—but believe they must do it by themselves. They strongly and wrongly believe that doing something on their own is better than succeeding with help. It may sound silly (no man is an island and all), but this is what a great many dysregulated eaters (and others) think. The idea of meeting with a dietician or working with an exercise trainer gets translated in their minds into meaning, “I guess I’m a failure because I can’t solve my eating and weight problems on my own.” They’re so ashamed that they can’t manage their food concerns that they think asking for help will make things worse and only view success as something they’ve achieved single-handedly. They honestly believe that if they get help, they’re not really earning success.

They may be slightly more open to help when it’s normalized and universalized by you, the practitioner—for example, if you were to say that you hardly expect patients to resolve these problems on their own and that there’s nothing in the least unusual about seeking or benefiting from support. You might even suggest that if you were in their shoes, soliciting help is exactly what you’d do. It’s fine to say, “I think we all need help on some things. I know I do.”

One more factor, which is perhaps more attitude than skill, is having a “growth” versus a “fixed” mindset. Stanford University developmental psychologist Carol Dweck, Ph.D., writes about them in her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success.18 People with a fixed mindset see themselves and their attributes or inadequacies as more or less permanent—they’re good at some things and bad at others, outgoing or shy, lovable or unlovable. They view their successes as a “reflection of their more or less immutable gifts or talents” and their failures as a “reflection of unchangeable deficits and weaknesses.” So many dysregulated eaters have this kind of fixed mindset: they’re either one way or another and mostly do not feel good enough about themselves. Desperate to succeed, they’re thrilled and relieved when they do and feel awful when they don’t, as if failure confirms what they knew all along—there’s something permanently defective about them.

Fixed-mindset thinkers might say to themselves, “I don’t exercise because I’m lazy.” A growth-mindset thinker would say, “I need to develop better strategies for getting myself to exercise because the ones I’ve been using aren’t working very well.” “People with a growth mindset explain their successes entirely differently, as the result of conscious, actively chosen behaviors and strategies.” They attribute their success to having practiced a lot, made healthy choices, or thought more rationally. “When growth-mindset thinkers fail, they don’t blame their intrinsic inadequacies but look for different strategies to succeed as in ‘I could try. . . .’”

Of course, it’s not your job to teach life skills to patients. It is your job, however, to recognize how deficits in these skill sets strongly and inevitably will impair patients’ ability to take better care of their health for the long term. Moreover, by understanding that we all have some form of life-skill deficits, you might have more compassion for your patients (and yourself) and less frustration when they feel overwhelmed with expectations or don’t follow your advice consistently. The best you can do is to take these patients as they are and try to nudge them along with your caring and compassion—and encouragement about baby steps. To learn more about life skills and their impact on food and weight, we refer you to Outsmarting Overeating—Boost Your Life Skills, End Your Food Problems by Karen R. Koenig. You may also refer to the training modules on Dr. O’Mahoney’s website at http://www.deliberatelifewellness.com.

WHAT MAKES A “NORMAL” EATER?

Most people use the terms nutritious/healthy eaters and “normal” eaters interchangeably when they actually have quite different meanings. As you learned in Chapter 4, on one end of the spectrum, dysregulated eaters seek food when they’re not hungry (mindlessly, emotionally, and compulsively) and often eat past full or satisfaction (overeating or binge eating). On the other, they deprive and deny themselves nourishment or food pleasure when they are eating restrictively (via diets). They fail to regulate their intake so that they eat just enough most of the time—to maintain a comfortable weight, derive sensory pleasure, feel satisfied with food or how wonderful it feels in their bodies, and nourish themselves effectively.

“Normal” eaters generally base their food intake on a combination of two specific areas of information: appetite cues related to hunger, cravings, food enjoyment, and fullness/satisfaction as well as rational thinking about food and weight. You may be wondering what’s with the quotation marks around the word “normal.” They indicate a set of internal guidelines (conscious or unconscious) on which food consumption is predicated—to (1) eat mostly when you’re hungry, (2) choose foods that satisfy you and feel good in your body, (3) eat with awareness and with an eye toward pleasure, and (4) stop eating when you’re full or satisfied. “Normal” could also be called regulated eating, but that sounds more like the timed feedings that pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock might have advised.

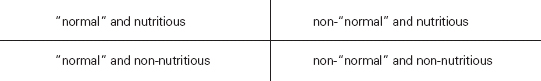

Nutritious eaters, on the other hand, choose foods exclusively for their nutritive value and are not necessarily “normal” eaters. Think of eaters as coming in four varieties: (1) “normal” and nutritious, (2) non-“normal” and nutritious, (3) “normal” and non-nutritious, and (4) non-“normal” and non-nutritious.19

Non-“normal,” non-nutritious eaters listen neither to their appetite signals nor care about eating what we would call a healthful diet. Non-“normal,” nutritious eaters disregard appetite cues, but choose mostly foods that will nourish their bodies effectively. They may nosh mindlessly on fruits and veggies all day long, never pass the refrigerator without taking “healthy” food from it, and ingest huge amounts of foods that are nutritious but that make their bodies uncomfortable. “Normal,” non-nutritious eaters eat according to appetite but eschew nutrition guidelines. They may leave some of their fried calamari or hot fudge sundae and eat only half a white-bread sandwich with processed meat and gobs of mayo because they’re full. And, finally, “normal,” nutritious eaters consume food according to appetite and focus on choosing mostly foods of high nutritive value.

Obviously, you would like to move your patients in the direction of eating both “normally” and nutritiously. The best rule of thumb is to guide patients toward becoming “normal” eaters first and, when those behaviors have taken root—and only then—encourage them to tweak their food intake to gradually become more nutritious. If they move toward nutrition too quickly, it will feel like a diet (restrictive and deprivational) and they’re all too likely to rebel with rebound eating, consuming large quantities of non-nutritive food and falling back into old habits, failing to attune to internal appetite signals.

As you already pretty much know what constitutes a nutritious eater, let us focus on the profile of a “normal” eater. Whether they eat three balanced meals a day—morning, noon and night—or six small meals throughout the day, they follow their appetite signals for hunger, craving, food enjoyment, fullness, and satisfaction most of the time. They may do this consciously or unconsciously, whether eating alone or with people, whether they’re stressed or relaxing, and whether they’re at home or on vacation. The crucial point is that the locus of control over their eating is within them, not based on some diet plan or program.

They plan ahead so as not to be starving for long periods of time and don’t care for that bloated, full feeling. Tasty satisfaction from a holiday meal brings a smile to their faces, but so do many other activities, and their main source of pleasure in life is not food. Sometimes they put off eating because they’re too busy, and other times they eat when they’re not particularly hungry because food will not be accessible when they might be later on. They are not perfect eaters, as if there were such a thing, and don’t even think about perfection. They are as likely to occasionally overeat as under-eat but pay these behaviors no mind.

They believe that food is mostly for nourishment and occasionally for pleasure, and may have concern for their weight, but don’t base their eating on it. If their weight decreases, they don’t think, “Oh, boy, I can eat more,” and if it increases, they don’t panic that they need to rush into diet mode. If they do weigh themselves, they don’t give the number on the scale the power to make or break their day. They eat without shame, and may be interested in what their dining companions are eating, but without such interest causing self-consciousness about their own food choice. They don’t think a cookie will solve their emotional problems, but occasionally seek tasty food just for the pleasure of it.

Understand that these “normal” eaters are not saints or paragons of virtue and may have multitudes of other problems. They may drink, do drugs, yell at their children, scam their employers, be rude to their neighbors, run afoul of the law, and be no one you’d ever want to talk with for more than a few minutes. The one problem they don’t have is with food.

Chapters 7 and 8 will teach you how to work with dysregulated eaters and point them in the direction of “normal” eating by getting them the help they need.

Brain food for providers: In treating patients with eating and weight concerns, can you see how lacking effective life skills makes it very difficult or even impossible for them to make the changes they need in their lives to improve or sustain their eating and health? How does this increase your empathy toward them? How does it change your approach to helping them?

Brain food for patients: Which of the above life skills are you missing or do you perform barely adequately? Do you have a better understanding now of how lacking effective life skills has made it difficult for you to take better consistent care of yourself? What steps can you take to improve them?

Providers, try . . .

1.Changing your conversation with patients from a weight to a health focus.

2.Getting a sense of what patients believe about food, eating, weight, and their appearance.

3.Gently pointing out how having healthier (i.e., rational) beliefs will help them eat more healthfully and take more consistent care of their bodies.

4.Fostering the healthy or realistic beliefs of your patients (which may well mean understanding and changing your own belief system on eating, fitness, and weight).

5.Eschewing use of “good” and “bad” when talking about food and replacing these words with “more and less nutritious,” taking the focus off morality and putting it where it belongs, on health.

6.Gently encouraging patients to speak kindly and compassionately about their bodies no matter what their size.

7.Helping patients focus on improving the life skills they lack.

8.Helping patients identify mixed feelings about consistently eating better, getting fit, and improving health care habits.

9.Identifying eating disorder therapists in your community who understand internal conflicts that your patients may have about food and the scale and referring your patients to them.

Patients, try . . .

1.Listing your beliefs about eating, food, weight, and appearance and determining which are rational and irrational. Use The Rules of “Normal” Eating to reframe beliefs from irrational to rational.

2.Feeling proud that you’re trying to change beliefs rather than feeling ashamed of what you’ve believed.

3.Exploring and reframing your unhealthy beliefs, improving your life skills, and resolving your mixed feelings about food and your body with a psychotherapist or coach.

4.Digging deeply within yourself and identifying what your mixed feelings are about food, weight, eating, and appearance, and reading Starting Monday to resolve them.

5.Instead of feeling ashamed that you have mixed feelings, life skill deficits, or unhealthy beliefs, feeling proud that you’re trying hard to improve in these areas.

6.Letting your doctor or health care provider know that you’re aware of conflicting feelings around food and weight and that you’re working to resolve them.

7.Using the self-assessment in Outsmarting Overeating by Karen R. Koenig to identify which life skills would help you have a better relationship with food and your body.