Figure 2.1

Playful user interfaces.

2 Playfulness

An iPhone is just a rectangular piece of metal, glass, and plastic; a machine with few moving parts, it does not hint at its potential functionality when it is turned off. But when it’s turned on, when software appropriates the hardware,1 an iPhone is a machine of almost limitless capabilities. It is a tiny computer equipped with a web browser, a music and video player, a gaming console, a lever, a calculator, a camera, and any other thing that Apple allows it to be.2 An iPhone, or any other smart phone, is the ultimate toy: an empty shell ready to be modified by the power of software.

The case of smart phones illustrates not only the malleable nature of toys as playthings, but also the capacity for some objects to afford playful behaviors. But what do I mean by “playfulness”? The relation between play and playfulness, more than just a casual affair, is extremely important for understanding the ecology of play and playthings.

Many of the technologies that surround us today are somewhat invested in looking like something other what they are or what they can be. A phone does not want to be a phone but a multimedia emotional companion. A television wants to be more than a fireplace substitute: it aspires to become the grandmother that tells the bedside stories you want her to tell you whenever you want. A fridge will take care of your diet, and your computer is an expressive extension of yourself. Your espresso machine probably loves you.3

We live in an era dominated by emotional designs—by objects created with the intention of appealing to our senses and feelings.4 A typical rhetoric of this postfunctional design makes technologies look and feel more playful. The many animations on the user interface of Apple computers, from the opening of a folder to the minimizing of an application (figure 2.1), are not purely functional design decisions. These user interface designs are driven by a desire to signal that the machine we are interacting with is not a serious computer but something else—something quirky and with personality that will not reject the form of expression through it but will actually encourage creativity.

Figure 2.1

Playful user interfaces.

Tapping on our emotional attachment to things through design is not exclusive of digital technologies. Workplaces and service providers of all kinds want to establish relations where customers or employees feel like play pals rather than mere numbers or cogs of a machine.5 Modern corporate values are strangely resonant of ideals related to good teammates, that is, to sports and games.6 We want our modern lives to be dynamic, engaging, and full of the expressive capacities of play.7 But we also want them to be effective, performative, serious, and valuable.8 We need play, but not all of it—just what attracts us, what makes us create and perform and engage, without the encapsulated singularity of play.

What we want is the attitude of play without the activity of play. We need to take the same stance toward things, the world, and others that we take during play. But we should not play; rather, we should perform as expected in that (serious) context and with that (serious) object. We want play without play. We want playfulness—the capacity to use play outside the context of play.

Playfulness is a way of engaging with particular contexts and objects that is similar to play but respects the purposes and goals of that object or context.9 Colloquially, playfulness can be associated with flirting and seduction: we can be playful during sex, or marriage, or work, though none of those are play. We can be playful with language through satire and puns,10 and even in the way we engage with our productive labor.11 However, those activities are most certainly not play; they are flirting, sex, and labor, and thus they have other purposes.

There is an important distinction to be made here. Playfulness is a physical, psychological, and emotional attitude toward things, people, and situations.12 It is a way of engaging with the world derived from our capacity to play but lacking some of the characteristics of play. Intuitively, we can feel the difference between play and playfulness. We can also have the vague idea that we can be playful even when playing. Somehow these two concepts are overlapping, but they are not referring to the same thing.

The main difference between play and playfulness is that play is an activity, while playfulness is an attitude.13 An activity is a coherent and finite set of actions performed for certain purposes, while an attitude is a stance toward an activity—a psychological, physical, and emotional perspective we take on activities, people, and objects.

From the bully to the socially awkward, to the seducer or the curious, attitudes are somewhat similar to the frames we use to make sense of our social and cultural presence.14 We talk about people “having an attitude,” and product marketers want to change our attitudes toward forgotten brands. Attitudes are projected on the world, and the world can resist these attitudes.15

In this sense, playfulness is projecting some of the characteristics of play into nonplay activities. It is an attempt to engage with the world in the mode of being of play but not playing. Sometimes that means to be playful when playing. We are playful in play contexts that are very strictly typified, in which play is bound by the strong enforcement of its structures. For instance, playfulness can take place when games are played or when sports are practiced.16 Athletes can be playful when they perform in ways that are not optimal for reaching their purpose. Many of the flourishes with which Magic Johnson adorned his basketball game were not practical and goal oriented; they were a show for the gallery, a way of enjoying the game while playing it at the highest stakes. This beautiful playfulness created a stark contrast with the serious context of professional play, making those actions more beautiful and an embodiment of the ideal of the game.

Players of a game are playful when they consciously manipulate the relative rigidity of the system. Dark play is used as a playful approach to play situations, in which the disruptive nature of play can be used to break the conventions of gentrified play contexts. An interesting example of this understanding of play comes from the story of a group of friends who have played tag for twenty-three years.17 For a month every year, a group of old friends play a game of tag that involves, without making them players, their families, friends, and coworkers. And not only are there players who are not playing (such as wives who act as spies but cannot be It), but also players who don’t know they are playing. The employers of these men did not necessarily know about the game being played and involuntarily become pawns in the game. Imagine if the people around you were in fact playing a game you were not aware of. Imagine those multiple worlds being experienced at the same time.18

Another case of dark playfulness could be Antonin Panenka’s famous penalty shoot in the 1976 Eurocup final against West Germany. Panenka not only made a beautiful gesture when the stakes were highest, he also playfully teased the rival’s goalkeeper in a stretch of what is acceptable by sportsmanship values.19

In our computational age, playfulness can be seen as a play-inspired revolt against the dictates of the machine. The computer, through seductive functionalities and hidden ubiquity, shapes the tasks we perform as much as we delegate to them.20 In this context, playfulness is a carnivalesque attack on the seriousness of computers, on the system-driven thinking that gives maximum importance to the dictates and structures of a formal structure. I am not writing here about playful user experience design, but about a darker, more explorative, and expressive approach to our relations to machines. Playfulness can be a revolt, a carnivalesque exploration of the seams of the technologies that excel at performing operations but limit the expression to that which is computable.

A good example of digital playfulness is Matteo Loglio’s DIY (do it yourself) project FAKE COMPUTER REAL VIOLENCE.21 This project connects an accelerometer to a computer microcontroller in order to measure movement and respond to it, in this case by sending a command to the operative system to restart. The fun aspect is that the project should be placed in a computer case, so when the computer freezes, a physical blow to the case will take us to the restarting menu—effectively responding to our violent attack on the machine. This ironic commentary on our perception of computer failure and our common violent reactions to it playfully allows us to restart our computer by hitting a specially designed USB extension. Equipped with an accelerometer, this extension reacts to the blows of the user by restarting the computer, effectively acting on the user’s violent reaction toward the machine.

Playfulness is the carnivalesque domain of the appropriation, the triumph of the subjective laughter, of the disruptive irony over rules and commands. Playfulness means taking over a world to see it through the lens of play, to make it shake and laugh and crack because we play with it. Some objects allow us to see the world through a playful lens; some contexts are more prone to playfulness than others. A classic Goffmanian example would be a Christmas dinner at a company, which is an opening for playfulness in the context of corporate life. It could be argued too that bulletin or image boards on the Internet, particularly those that have strong anonymity settings, encourage a certain playful behavior from the user—one that can range from silly YouTube videos and comments to the more interesting and complex dark play practiced on occasion in 4chan.org, an image-based bulletin board.

Playfulness glues together an ecology of playthings, situations, behaviors, and people, extending play toward an attitude for being in the world. Through playfulness, we see the world, and we also see how the world could be structured as play. Brendan Dawes’s Accidental News Explorer is an app that pulls random pieces of news from different sources (figure 2.2).22 It provides users with a single input box where they can type a keyword, and the software will find the news for them. It is hardly the most functional news reader ever developed, yet this serendipitous approach to news forces us to look at its choices with playful astonishment: how could a machine find the news? The news can be playful too.

Figure 2.2

The Accidental News Explorer.

For the playful attitude to exist as related to the mode of being of play, it needs to share some traits with play. Since playfulness is an attitude that projects some of the characteristics of play into the world, understanding which characteristics of play constitute the playful attitude will allow us to better understand the function of playfulness in the ecology of play.

Let’s start where play and playfulness diverge. Play is autotelic, an activity with its own purpose. We play for the sake of playing. Since playfulness is an attitude, a projection of characteristics into an activity, it lacks the autotelic nature. Playfulness preserves the purpose of the activity it is applied to: it’s a different means to the same end. If it is sex, then the pleasures of sex are the main purpose even if we are playful. If it is using a computer to write a book, the purpose is still writing regardless of how playful we are in the process. Playfulness is not autotelic because it is not an activity. Furthermore, for it to be a productive way of being in the world, it needs to respect the purpose of the activity it is applied to. Otherwise playfulness becomes a destructive force, not engaging with the activity or with the creative capacities of play.23 Playfulness always respects the purpose of the activity for its own integrity to exist.

This does not mean that playfulness cannot be disruptive. In many cases, a playful attitude will result in a relative disruption of the state of affairs, though without destroying it. The art project My Best Day Ever, by Zach Gage, “automatically searches twitter for the phrase ‘my best day ever’ and then picks a tweet it likes, and re-tweeters the tweet as its own,” as the author describes it.24 My Best Day Ever is a playful commentary on Twitter, privacy, and our desire to reach out through impersonal and technologically mediated mechanisms. It also shows personality by selecting appropriate tweets and a certain degree of self-irony. It somehow disrupts Twitter as a medium without destroying it, revealing the self-imposed honesty of these media. The activity needs to exist, to be finished, for the playful disruptiveness to be effective. Otherwise it is just destruction, a nihilist attitude different from the creative approach that playfulness affords.

So what does playfulness bring to these other activities? Why does playfulness matter? Playfulness assumes one of the core attributes of play: appropriation. To be playful is to appropriate a context that is not created or intended for play.25 Playfulness is the playlike appropriation of what should not be play. Brendan Dawes’s DoodleBuzz is a “typographic news explorer” in which users can find news pieces by drawing doodles on the web browser canvas.26 Again, news reading through DoodleBuzz is significantly different from reading it through a conventional news reader; however, the physicality of the interaction (drawing doodles) and the serendipity of the underlying system contribute to the playful experience. Reading news is not supposed to be physical, or drawn by chance. News reading ought to be effective, functional—unless, of course, we want our news consumption to be personal, expressive, and appropriative and to make the news ours by drawing it.

In playfulness, appropriation happens in its pure form, taking over a situation to perceive it differently, letting play be the interpretive power of that context. Appropriation implies a shift in the way a particular technology or situation is interpreted. The most usual transformation is from functional or goal oriented to pleasurable or emotionally engaging. Appropriation transforms a context by means of the attitude projected to it.

Playfulness reambiguates the world.27 Through the characteristics of play, it makes it less formalized, less explained, open to interpretation and wonder and manipulation. To be playful is to add ambiguity to the world and play with that ambiguity.

In this sense, the difference between contexts needs to be specified. Play happens in contexts created for play, in those contexts in which the autotelic nature of play is respected.28 Traditionally these contexts are games, but they can also be playgrounds or temporal contexts such as the lunch break: openings in time and space where play becomes possible. The contexts in which playfulness happens are not designed or created for play: they are occupied by play.

We occupy contexts through playfulness to be creative or disruptive. A PowerPoint presentation can be a dry showcase of charts and numbers, or a dynamic visual experience of data.29 Similarly, data visualization has become a contemporary playground for the exploration of how data can be made significant and more visible through playfulness. Projects like Live Plasma,30 a visualizing tool that helps recommend music to users, or Twitter Earth,31 a tool that locates a tweet on a three-dimensional representation of the globe based on the location data embedded on the tweet, are examples of playful interpretations of data. This approach is also closely related to the aesthetics of play and playfulness. Julian Oliver’s Packet Garden visualizes network traffic by growing a world, each network package or communication activity translated into a geographical or ecological element of that world.32 Uploads are hills, and there are HTTP plants and peer-to-peer plants.

These are creative appropriations of data through playfulness, revealing new knowledge through play. Playful appropriation allows for the expression of idiosyncrasies in even the most rigid of contexts. Through playfulness, we open the possibility of expressing who we are. Even in instrumental situations, personality is tied to performance, to the fulfillment of schedules. Playfulness frees us from the dictates of purpose through the carnivalesque inheritance of play. Through playful appropriation, we bring freedom to a context.

Playfulness can be used for disruption, revealing the seams of behaviors, technologies, or situations that we take for granted. The Newstweek project literally takes over open wireless networks to playfully manipulate news consumption (by manipulating the headlines of major news providers in real time), shattering our assumptions on networks, news, and consumption of stories through online gatekeepers.33 Similarly, Moss Graffiti can take over spaces such as parks, often carefully walled against their own users, and make them playfully public again.34 Through playfulness, we incorporate a personal view into the situations we live in. Playfulness, like a carnival, is an opening toward critique and satire, toward freedom in the context of mundane activities.

There is one last characteristic of play that is present in the playful attitude: play is personal, and playfulness is used to imbue the functional world with personal expression. If we look at the evolution of modern personal computing, from the desktop to the mobile, we see how machines have become more flexible toward personalization. We can change screen backgrounds, or ring tones, and through them we express ourselves. The temporary popularity of using an old-fashioned ringing sound with a modern mobile phone was a way of playfully relating to the machine itself and its nature. The dissonance between technology and sound was supposed to be not only ironic but also personal.

Through playfulness we personalize the world; we make it ours while still acknowledging that it has a purpose other than playing. Through playfulness, we bring the creative and free personal expression that play affords to a world outside play, and therefore we make the world personal.

Of course, the world might resist. In fact, many situations, contexts, and objects are specifically designed to resist playfulness; the instrument panels of planes or other critical systems should not be toyed with. Regardless of the positive values we give as a society to creativity and play, there is still a tension between labor and expression, between functionality and emotions. The functional tradition in design focused on efficiency and productivity.35 This modernist dream is Tati’s nightmare in the film Playtime, which chronicles the slow but finally triumphant flow of play in the rationalist world of modernist France. That was a world in which technology guided people through the straps of daily production and efficiency. Playtime is a song of freedom, an ironic view on playfulness taking over the dullness of everyday life. That is why playfulness matters: it brings the essential qualities of freedom and personal expression to the world outside play.

The traditions in design, however, seem to focus on preventing playfulness, on resisting by design the temptation of appropriation. Even Apple computers, the most voluntarily playful of computing environments, are carefully engineered to allow only certain sanctioned types of playfulness. More than a prop for play, Apple technologies, like so many others, present themselves as a referee more than a player.

Designing playfulness is more complex than what it might seem. One of the advantages of functional design is the relative predictability of the outcome: because an object is designed with its function in mind, all of its elements are guided toward that purpose and all deviant behaviors can be minimized. Household appliances are often good examples of this, easing our daily tasks but not necessarily enhancing our experience of the mundane. When I compare my fridge or dishwasher with my computer or a car dashboard, I can see how performance is paramount to the design. I do not care about my fridge; I have no emotional feelings toward it. It is functional but not emotional.36

Playful designs are by definition ambiguous, self-effacing, and in need of a user who will complete them. Playful design breaks away from designer-centric thinking and puts into focus an object as a conversation among user, designer, context, and purpose. In fact, what playful design focuses on is the awareness of context as part of the design. Rather than imposing a context, playful designs open themselves to interpretation; they suggest their behaviors to their users, who are in charge of making them meaningful. Playful designs require a willing user, a comrade in play.37

This approach to design downplays system authority,38 a minor but crucial revolt against the relative scientism of design, from games to word processors.39 Playful design is personal in both the way the user appropriates it and the way the designer projects her vision into it. It’s a more challenging object, a statement about rather than an acknowledgment of function. In that gap, playfulness finds its grip to appropriate the object, to make it an expression rather than a product.40

Playful technologies are designed for appropriation, created to encourage playfulness. These objects have a purpose, a goal, a function, but the way they reach it is through the oblique, personal, and appropriative act of playfulness. They do not become toys or pure playthings, but the behavior and attitudes toward them, the ways they redefine the contexts in which they are applied, invoke the characteristics of play.41

Playful technologies are mostly extreme ideas implemented in the relative safety of academic labs and blue-sky projects.42 These are objects that work very well in controlled environments: the studio, the art gallery.43 But playful design still has to find its place in the uncontrolled environment of everyday life. We are comfortable with functionality, with surrendering our expressive capacities to objects that seem playful but are not radically so.

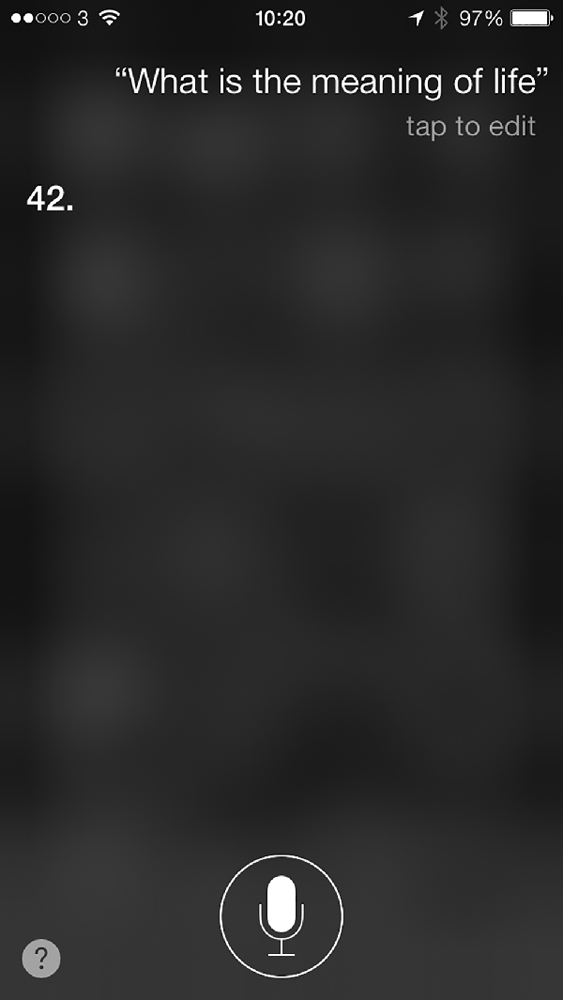

One of the most interesting examples is Apple’s Siri, the artificial intelligence helper. Introduced with the iPhone 4S, Siri is a voice-activated assistant that can help phone users perform mundane tasks, such as place phone calls, make appointments, or find locations. Technologically, Siri is an impressive achievement, but its playful design is even more interesting.

One of the most interesting examples is Apple’s Siri, the artificial intelligence helper. Introduced with the iPhone 4S, Siri is a voice-activated assistant that can help phone users perform mundane tasks, such as place phone calls, make appointments, or find locations. Technologically, Siri is an impressive achievement, but its playful design is even more interesting.

Siri could have been an efficient, task-driven system, a ruthless parser of voices that would neglect to recognize anything outside its instructions database. However, Siri’s designers are aware of the mischievous playfulness of users, and they prepared for it. Siri has answers for marriage proposals or questions about religion and the meaning of life (figure 2.3).44 Siri has a personality: she is quirky, ironic, even a bit dry. Siri is a playful design that breaks our expectations and gives personality to software. It is far from being an ideal playful design, because it resists extreme appropriation (users cannot program Siri, and Siri is one for all users). However, it is a successful commercial product that defies conventionalism regarding functionality and personality. By being playful, Siri becomes a companion more than a tool.45

Figure 2.3

Siri is a geek.

We need more objects that allow us to be playful. We need to take the capacity of appropriation and make a world that does not resist it. At stake is more than our culture of leisure or the ideal of people’s empowerment; at stake is the idea that technology is not a servant or a master but a source of expression, a way of being. These designs need to exist so we can make technologies ours, and our being in the world a personal affair.

Playfulness allows us to extend the importance of play outside the boundaries of formalized, autotelic events, away from designed playthings like toys, or spaces like the playground or the stadium. It effectively allows seeing how play is a general attitude to life. Playfulness expands the ecology of play and shows its actual importance not only in the making of culture but also in the very being of human, on how being playful and playing is what defines us. We are because we play, but also because we can be playful.