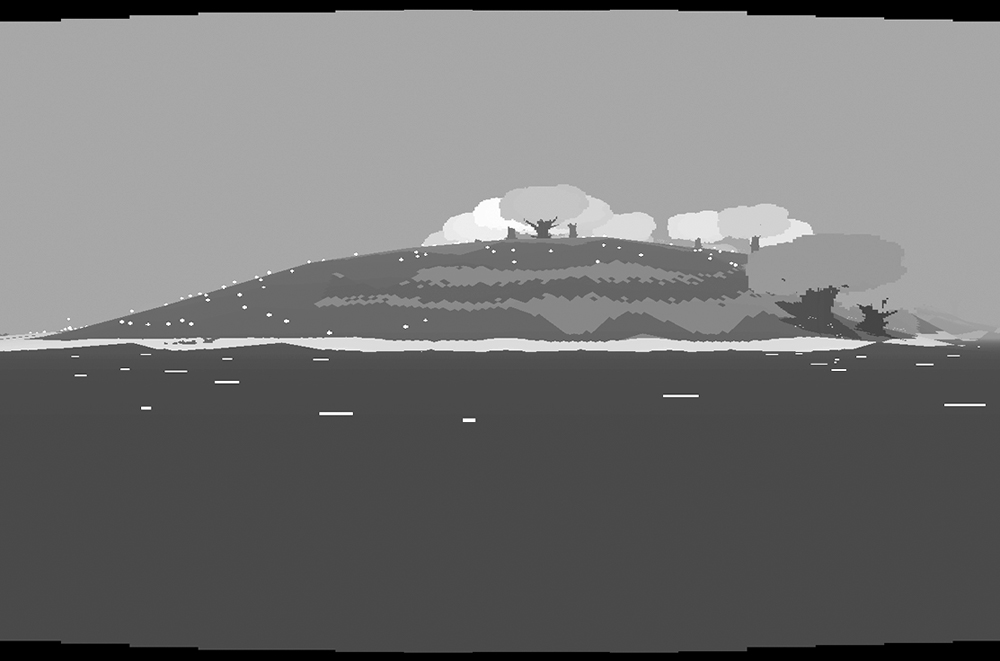

Figure 4.1

A ship sinks in a playground.

4 Playgrounds

The ship is sinking! Fast, let’s run to the moai. We will find shelter there from the pirates … but where are you? Around which corner? Ah! There you are, hiding in the open belly of the ship! That was a good scare! What now?

All of these things happened to my oldest son and me on the same day in Copenhagen.

On a playground.

Our adventure took place in a legeplads (a Danish word that literally means “a playground”) in the East of the city on a warm autumn day.1 On our way to a family event, we had stumbled on a fantastically dramatic playground, a festival of shapes and structures organized around a sinking ship (figure 4.1) and a big statue like the moai on Easter Island.

Figure 4.1

A ship sinks in a playground.

The work of Danish playground designers Monstrum is astounding.2 Not only they are able to infuse their structures with personality and charisma, but they also provide a dramatic setting for play that adults and children can enjoy together. Monstrum produces brilliant iterations of adventure playgrounds.3

But this chapter is not going to focus on the history of playgrounds. I want to think about play and space using playgrounds as both concrete examples and metaphors that explain the relationship between play and designed spaces.

So far in this book, I have focused on defining play and playfulness and how the activity and attitude can be cued by the design of playthings. But where do we play, and how are those spaces designed? I don’t want to think about game worlds, virtual or not, or about sports arenas. Those are spaces created for play, yes, but I aim at a more abstract and open category—at a parent species of all the different iterations of spaces for play. I want to reflect on how play modifies and is modified in and by physical or virtual environments.

Playgrounds are the most appropriate metaphor for understanding the interrelationships between play and actual playgrounds, but also skate parks and parks taken over by skaters or parkour traceurs (the moniker used for practitioners of parkour, the popular sport that uses city architectures for athletic explorative running) and, of course, virtual environments.

To understand the relationship between space and play, we need to return to two of the main arguments of this book: play is appropriative, and play takes place in the context of things, cultures, and people, in time and in space. The first fundamental distinction that we need to make is that between play spaces and game spaces. A play space is a location specifically created to accommodate play but does not impose any particular type of play, set of activities, purpose, or goal or reward structure. Playgrounds are the most typical play spaces, though the presence of toys in, for example, a doctor’s waiting room is an invitation for the child (and the parents) to appropriate that space through play, to turn it into a play space.

A game space is a space specifically designed for a game activity. The size, measure, props, and even location are all created with the purpose of staging games. A game space can be created with the purpose of satisfying just one game, like some football stadiums in Europe, or with the purpose of supporting a multiplicity of games, like the old Roman arenas. Of course, the fact that game spaces are designed for games does not prevent them from being turned into play spaces. Again, play spaces are created when a space is appropriated though play.

In the digital realm, we could talk about the absolute dominance of game spaces over play spaces, from Doom to Medal of Honor. Most virtual game worlds are created to support a particular game, and the craft of level design is focused on the design of game spaces. Play spaces, however, are also an important tradition in virtual worlds. “Sandbox” games in which players can more or less freely roam an expansive virtual environment, like Grand Theft Auto and Fallout 3, are both game spaces and play spaces, and these are not the only games to include both spaces. Software toys like Sim City and other procedural toys are also play spaces to a large extent—spaces of possibility created to explore with rules in order to see what happens. Play spaces in digital games are linked to emergent behavior on both the material side (how the system behaves) and the user side.

The relationship between space and play is marked by the tension between appropriation and resistance: how a space offers itself to be appropriated by play, but how that space resists some forms of play, specifically those not allowed for political, legal, moral, or cultural reasons. Play relates to space through the ways of appropriation and the constant dance between resistance and surrender.

Let’s return to the Danish Monstrum playgrounds, which are spaces designed for children to appropriate. They signal paths, activities, challenges, and possibilities; one can crawl, jump, creep up, roll, and fall in ways that the space suggests but does not determine. The dramatic flare of these playgrounds also indicates ways in which they could be appropriated. A sinking ship and a moai immediately invoke a set for imagined adventures where older kids can play pirates. The structure of these constructions encourages the creation of games of capture the flag, hide-and-seek, and tag. Different geometries and locations of the structures on the playground suggest many kinds of potential interactions. Both the materiality of the playground and its aesthetic form are ways of resisting pure appropriation, used to cue behaviors and therefore experiences, through play. But of course, play can always overrule design and make a carefully designed space something totally different, though still a space for play.

If we look at how a playground is designed, we notice how play in space is often organized around props. In the case of the Monstrum playground, the ship, the moai, and the hanging ropes all build up toward a particular place, a particular sequence of activities that can be performed: jump from the boat to the moai, climb up, find the ropes, slide through them (figure 4.2). Vertigo, order, structure, and chaos: they all potentially reside in the way this playground is structured and are all potential outcomes of this space.

Figure 4.2

Moais to play with.

The way spaces are articulated for play is dependent on more than design or playful considerations. Strong norms, rules, and laws govern the use of public and private spaces, and play design must be done in accordance with them. The Monstrum playgrounds are certified as safe, so they are institutionally correct. In many cases, the trivialization of playground design—the overabundance of plastic-based, repetitive architectures built for safety rather than for play—which seems to have increased in the past several decades, is a result of protective laws rather than of misguided design.4 And the interest today in implementing digital playgrounds5 or computer-enhanced environments6 for play also comes from the normative idea that play is more secure if it is more controlled.

There is an interesting bit of history to this effect that helps explain how spaces are designed for play. Monstrum playgrounds, as well as many of the playgrounds I frequent in Copenhagen, are the latest iteration of a Danish invention, the adventure playground.7 Originally called “junk playgrounds,” these spaces were created by progressive Danish pedagogues who were interested in letting children express themselves through play by providing them with the tools to create their playground. That is, instead of giving them a slide and a tower, they gave the children saws and hammers and nails so they could build their own playgrounds.

The obvious dangers of this practice created an interesting ripple effect: all play in adventure playgrounds was supervised by an adult. In this way, safety was moderately ensured. But this also meant that the children’s play was monitored and potentially interfered with.8 This is not a tale of absolute child freedom but an illustration of the careful balance needed when letting children be exposed to the creative, and potentially destructive, capacities of play.

Adventure playgrounds were adopted in Britain after World War II thanks to the efforts of Lady Allen of Hurtwood. After observing the Danish experience with adventure playgrounds, she imported the concept with two purposes. First, she saw these playgrounds as a way to help children reintegrate through play in constructive society after the war by letting them enjoy a larger degree of freedom than that granted in Victorian playgrounds. Second, playgrounds served as urban renewal projects since most of them were created in the shelled craters of bombed cities.

Certainly the history of the adventure playground is fascinating on its own, but the reason I invoke it here lies closer to my own understanding of play. Adventure playgrounds help us understand how spaces can be designed for play through the use of props that help play take place within a bounded space while still remaining open to the creative, appropriative capacities of the activity. Good playgrounds open themselves up to play, and their props serve as instruments for playful occupation.9

The question of how to design these spaces is an architectural one.10 We should worry about how a space is created for facilitating play while complying with the different normative frames in which play takes place. This is a challenge, since norms and regulations are often conservative estimates based on the types of play we deem correct,11 and often those are based on fear rather than on the potential for play to be an expressive way of being in the world.

Playgrounds are interesting because they are spaces designed for appropriation. However, we should not underestimate the capacity of play to appropriate the world outside the environments we create for it. Think about urban sports, from skateboarding to parkour. Both sports play with space or, more appropriately, appropriate the space of the city in order to perform play activities.

Skateboarders are masters at seeing the playground in the urban spaces that surround them.12 A rail is for play, and so are stairs. The more public and the more complicated the space, the better the play is. Some cities have built expensive skate parks, yet on weekend nights, you can find teenagers revealing to us how mundane our public environments are, for what we think is a square is just a reflection of our own view. To these young people, it’s not a square; it’s a playground, and it is theirs.

Similarly, parkour appropriates and reinterprets urban spaces, making the architecture of the city not only an obstacle but also an expressive instrument.13 Although many cities are now building parkour playgrounds, it is the urban space where the traceurs find the most interesting routes to express themselves. The importance of recording and sharing the different feats is connected to the deeply embodied experience of the space that parkour promotes. Parkour is about the traceurs taking over an urban space together, making it a canvas for bodily expression

The next step in thinking about playgrounds comes from the digital domain. Computers have allowed us to create increasingly sophisticated virtual worlds. These worlds are mostly created for playing. One could argue, in fact, that one of the main contributions of computing to the history of games is the capacity to create complex, interactive worlds.14

It is not my intention to go deep into computer games in this book; after all, they are just a tiny subset of playthings. But I briefly reflect on how computers help create both game spaces and play spaces and why playgrounds are good metaphors to understand them.

I first focus on video games that offer an open world that is not structured exclusively around the form of a game but a world that contains a game, or many games. Grand Theft Auto, Fallout 3, and even most massively multiplayer online games are, to a certain extent, sandbox games. They are interesting because their design is the digital implementation of the idea of a space open for appropriation yet populated by props that help steer predetermined activities.

Think about Grand Theft Auto: although the game wants us to follow its linear, narrative structure, the storytelling nodes that move the plot forward are in fact props, like all the other things in that world for encouraging play. The narrative takes us into a game with form and structure, but we don’t need to engage with it. We can take another route and see what happens, as we would on a playground.

Software toys share this nature. Sim City encourages players to develop the city, which provides interesting challenges and audiovisual positive feedback when the city becomes larger.15 However, much of the joy in interacting with these procedural toys comes from testing their very propness as we figure out where the seams are and what we can build with them. They are somewhat like adventure playgrounds, giving us a hammer and some nails while a vigilant adult makes sure that we are never idle or that we use the hammer on our best friend’s head.

A different take on the playground can be found in experimental games that use the computer’s capacity to create virtual spaces to provide not a tempting dance between structured and unstructured play but a more contemplative experience. These are games on the limit of being playgrounds. They could be perhaps better understood as a concept between a playground that uses the conventional rhetoric of play and a romantic garden designed for suggesting potential but never actual activities. I call these emotional playgrounds: spaces designed for using the experience of play rather than its form to create emotions.

The video game Proteus (figure 4.3) is an example of this kind of emotional playground.16 In Proteus, players are free to wander around a computer-generated island with birds and butterflies; stones and trees; snow and rain and sun; and seasons and stars. The Proteus player, accompanied by music, sets off to fulfill his or her goal of exploring a world.

Figure 4.3

Entering the world of Proteus.

Proteus is interactive software that delivers an experience to which we open ourselves; we cocreate an experience while engaging with that world in the mood of play. Proteus uses play to explore emotions—in my case, longing, the pleasure of solitude, and inner peace. Walking in Proteus is walking in a playground designed to explore not the props laid out and placed there by the creator of the space to interact with but a playground designed for us to fill with our own emotional props, which can then be experienced through play.

Proteus is a way forward in digital world design. By harnessing the world-creating capacities of software but focusing on the emotional capacities of play, Proteus invites us to explore through play and allow ourselves to enter a state in which we become the subject of experience and inquiry. The beauty in Proteus comes from its openness to us to take it over and complete it.

Computers might have afforded a whole new way of understanding and creating playgrounds. The capacity of programmers to write their own physics and logic makes it possible to create worlds with different coherences from ours, that is, with different laws of physics, time, or even materiality. Digital playgrounds are still trying to formulate ways in which the important materiality of the props of material playgrounds can be substituted, to the same effect.

Playgrounds explain how materiality and activity are joined together in the selected spaces of play. Playgrounds as metaphors also allow us to escape from game spaces, which are designed for the purpose of playing games but do not always allow the exploration of the creative and appropriative capacities of play. If play spaces are defined by something, from skater parks to Proteus, that is the openness to appropriation, the ways in which they let us play, giving us a place to be.