TUESDAY

Years from now, at a critical stage in this book’s realization, I will cull from this manuscript ten theses about religious life at Graterford Prison. Here’s the first.

THESIS 1

Not only in our prisons are Americans crazy for God. We are a people who talk to God and to whom God frequently talks back. God talks to us through Scripture and through our waking thoughts and dreams. In our judgments about God, we are a remarkably confident people. We are generally confident that God exists, that He is personally invested in our lives, and that He reveals to us signs for discerning His will.1 When and where it sprouts, our disbelief in God tends to reflect this very same self-assurance.2

Religion at Graterford Prison exudes the confidence and creativity that has dominated American religion and spirituality for the last 200 years. Somewhat curiously, confidence often yields claustrophobia. At the shimmering shell of this phenotype, one finds the chaotic genius of confident men like Joseph Smith and Elijah Muhammad, iconoclastic visionaries unafraid to approach God without intermediary.3 At the hardened kernel lies the hermetic regimentation of the Nation of Islam and the Mormon Church. In America (and arguably in religion as such), innovation and authoritarianism go hand in glove.4 Religions at Graterford participate in this contradiction. Through the impulsive religious judgments of each man, idiosyncratic religious forms are emphatically embraced as but the recovery of ancient truths. No sooner are such judgments made, however, than the putatively self-evident character of the resulting truths is marshaled to preclude the sorts of spontaneous discernment through which the individual came by them in the first place.

Their many differences notwithstanding, Graterford’s predominant religious discourses—Salafi Islam and Protestant fundamentalism—share in this regard, too, a family resemblance. If, as a collective, the Salafi keep the Qur’an and hadith at the center of the recovery enterprise and the scholars bury their noses in the text, the rank and file seem contented with predigested doctrine. Ignorance of the tradition need be no obstacle to religious certitude. Similarly, with an interventionist Holy Spirit at work in a Bible believer’s heart, the Bible itself can become more or less redundant. Interiority is endowed with divine authority; common sense becomes law and personal experience its jurisprudence. And, indeed, with so many of one’s former friends and adversaries long since returned to dust, proof of His miracles is as plain as my next breath. As it is said: Because by all rights I should be dead ten times over, I know that God has a special plan for me.5

* * *

In the waiting room, a busload of black women, many draped in voluminous black fabric that covers all but their eyes, clutch their shyer children on their laps while throwing the occasional arm or rebuke in the direction of the more rambunctious ones.

Three steel doors and a long corridor away, meanwhile, the fifteen men gathered for St. Dismas Episcopal services are discussing what it takes to be a man. The brown-clad men fill most of the molded plastic chairs—colored tan, burgundy, and Pepto-Bismol pink—that line Classroom A’s wainscoted perimeter.

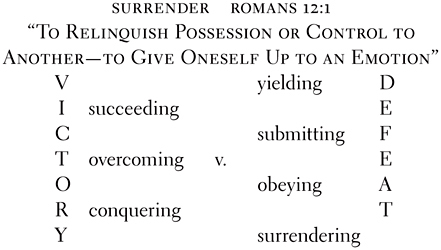

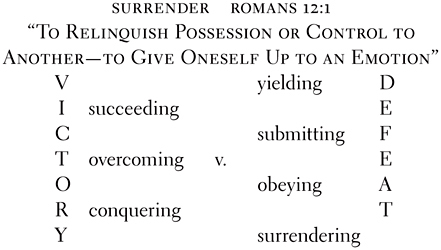

At the far end of the cramped classroom, the chalkboard reads as follows:

From the conversation under way, it is clear that contrary to conventional thinking of the vertical characterizations, the rightward column is where the praiseworthy behaviors lie.

Oscar is talking. Oscar is a flat-nosed, dreadlocked lifer, thirty years into his sentence for a homicide committed when he was fifteen. In the free-form exchanges at St. Dismas that precede the homily, in which few who talk come off as reticent, Oscar stands out for his candor.6 In his nasal but commanding voice, and favoring arresting hypotheticals along the lines of “Let’s say I kill you,” Oscar offers savvy testimony to the ways that a guy “gets caught up doing time.”7 With an emphasis on the everyday, Oscar stresses the inured passivity this place breeds; how via fear and prudence a man learns to shoulder petty humiliations and turn a blind eye to brutality.

“Yeah, we’ve got to surrender, like it says in Romans 8:36–39, but at the same time, like it says in Ephesians 6:11–13, we’ve got to be victorious against the devil. We’ve got to go like sheep. We need to die daily for Christ. We need to give ourselves up the way God wants us to give, not how we want to give it. I’ve been in the penitentiary almost thirty years, but it’s not for me to say that I want to be free. It depends on what God wants for me. But, you know, this is the thing that’s hardest for us to accept.” Leaning forward, he gestures at the other seated men. “We’re all warriors in here. I mean, why are the streets all full of women? Because the alpha males are all locked up in Gratersford”—as the old heads tend to, Oscar inserts a gratuitous “s” in the prison’s name. He points at the board. “You see the ‘V’? Well, that’s us: stuck right there in the middle. Trying to be victorious in the way that we want to be victorious. But it’s not about what we want. Cause when you surrender to Him, that’s real victory.”

Waving a rolled-up devotional pamphlet, another regular picks up the thread.8 “Surrendering means surrendering our desires just as He surrendered himself on the cross. You see, what we need is the daily sellout.” Consistent with the inversion of values being extolled, “selling out” here means not capitulation, as used to be said of hip-hop artists who crossed over to pop, but conviction. “Selling out” is the total commitment of self to a particular way of being in the world.

“That’s right,” pipes in the slim brown at the chalkboard. “We need to make an effort moment by moment. Like the moment I told you about earlier. It was eating me up. So I had to surrender, to apologize. I wouldn’t have done that in the past. But now I’m free of it.”

“Submission isn’t just a onetime thing,” a fourth man adds. “We’re going to be tried daily, and we need to deny ourselves daily.”

Paul’s demand to the Corinthians that they need die daily, that they redirect their will and desire away from the ephemera of the world and onto the Lord, carries additional resonance here, where, as Baraka says, serving impulse’s whim will get a guy sent to the hospital, to the hole, or to the morgue. In this light, Paul’s prescription in Romans—“For thy sake we are being killed all day long; we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered”—flips the “code of the streets” and furnishes for the men in this room a practical formula for surviving the abuses and humiliations of prison life. Whereas out on the street, to endure affronts without retaliation marked one as less than a man, here, in Christ, suffering is ennobled and self-sacrifice becomes self-mastery. Not merely a strategy for self-preservation, surrendering is the warrior’s way in the cosmological struggle between God and Satan.

“And the more we struggle,” says the brown at the board, “the more we’re tested by the fire—as it says in First Peter, Seven—the more we honor God. I used to think: ‘Lord, I gave myself to you, so why aren’t things any better?’ But it’s not like that! We must be led like lambs to the slaughter every day. Prosperity isn’t here on earth like they say in some of the churches. It’s waiting for us in heaven. But as long as we’re here, our relationship is between one another. We’ve got to learn to treat one another right. Despite all the nonsense we’ve done, God blesses us and watches over us and that’s how we’re still here. That’s by God’s grace. A lot of guys say, ‘I’m saved.’ But saved for what? You’ve got to be saved every day of your life!”

When the conversation dissipates, I trade discreet nonsense with Neil, who is seated to my right. Despite his thinning mess of cornrows, the wispy ends of which overhang his cloudy eyes, at thirty-five, Neil presents as, in effect, a boy. And so he is treated, by St. Dismas’s minister, Marcus Madison, at least, who frequently arrives with overbearing reports of e-mail exchanges with Neil’s mother. Neil, who speaks with the Pittsburgher’s Appalachian twang that never fails to exhaust the Philly guys’ ridicule, is St. Dismas’s worship coordinator—a position that consists largely of distributing prayer books and providing two of the four hands necessary for carrying in the table for Communion. When not in the chapel, Neil kills his time mostly among the small Dungeons and Dragons subculture on C Block.

Marcus Madison barges through the back door. Madison primarily ministers to St. Dismas’s sister congregation, St. Mary’s, an ailing brick structure in South Philly. Between gigs, Madison—a self-proclaimed bullshitter, so don’t try to bullshit him—drives around in a fir-green Acura with tinted windows and a bumper sticker that reads: REAL MEN LOVE JESUS. As though the topic is already on the table, Madison launches in on the subject of Christmas gifts. It is a selling point for St. Dismas that all congregants and their children receive something for Christmas.

First off, Madison says, he wants to apologize to those who didn’t get their packages.

“I thought that my family forgot me,” says the brown at the board, “but then I found out that the institution just didn’t deliver it.” He looks relieved.

In the future, Madison instructs the men, they need to make sure to print their names rather than writing in cursive. They also need to make clear to their families what is permitted and what is not. The institution simply will not allow in anything decorated with tape, stickers, or glitter.

* * *

A triumphalist-sounding tape-recorded organ track emanates from Classroom B, where the Jehovah’s Witnesses are meeting.9

Standing in the narrow passage between the two classrooms, I peer through the gap in the drawn curtains, but don’t consider joining the half dozen worshippers on the other side of the glass. While men who worship are free to come and go as the spirit moves them, once the door to Classroom B shuts at 9:00 sharp on Tuesday and Thursday mornings, it does not generally reopen until the service is done.

Suddenly, Jack, the Catholic Christian Scientist, is at my shoulder. “Remember what I told you about the Jehovah’s Witnesses?” he asks.

A month ago, in the course of his custodial duties, Jack took me aside and told me in the most serious of tones that something “you need to note in your report” was that in contrast to every other denomination, the Jehovah’s Witnesses were punctilious about cleaning up after themselves.

“Rest easy,” I assure him, “I’ll be sure to indicate that they always clean up after themselves. Not like these…” I wave my hand around the chapel in search of the appropriate term of derision. Jack beats me to it.

“Protestants!” he barks.

* * *

The chapel is bright. Color pours in through the stained glass flanking the altar, projecting watercolor splotches of orange, green, blue, and purple onto the crushed-stone floor. In the front-right corner, where small groups congregate, a blue is preaching the Word.

Known for their navy pants and periwinkle shirts, the “blues” are the twenty percent of Graterford’s population that are here for violating their parole. As classified but conceivably misplaced men, who, upon arrival, might or might not be in substance withdrawal or be nursing an old beef with another Graterford resident, the blues live sequestered on E Block; they don’t work jobs. Until recently, they were barred from all chapel activities too, but after successful lobbying by Baumgartner, they were welcomed to the most popular worship services—the Thursday-night Spanish service, Jum’ah, Catholic mass, and the Sunday Protestant service—venues that furnish their only sanctioned contact with the browns. After further petitioning, the institution also okayed a Bible study, which last month was moved off of E Block and into the chapel.

The preaching blue is young, by chapel standards, soft-spoken, and, like everyone else clustered in the corner of the chapel, black.

“The devil is trying to take away from us, all day long. We need to stand with the bell of truth. Satan fights with lies.”

Behind the blue, a second chalkboard offers another set of clues:

Phil 4:13

John 15:4–5

Luke 17:32

Hebrews 11:25

Ephesians 6:3–17

Phil 4:13

Subject: Ten ways to go into 2006 under God’s supervision

A list of proof texts for some contention left undeclared. Were I among the initiated, I would be able to extract the thrust of these selections just as an avid baseball fan might reconstruct from this morning’s box score the ins and outs of last night’s game. On a snowy night under a desk lamp in my basement apartment, I will crack the code. Philippians 4:13 is the key.

I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me. It is a declaration that creates—or aspires to create—the new man it describes.10 For those who, in John’s language, have been “regrafted to the true vine,” who, as Paul put it to the Ephesians, have “donned the armor of God,” the affirmation divides one’s life into two very unequal parts. There were all the moments prior to one’s rebirth when failure was assured, and there are all the moments from here on out when success is achievable, so long as one keeps his focus on the here and now. Outfitted with the sword of the Spirit, the new man may be confident that he is up to the task.

This, as it is generally called, is “transformation.” Transformation, as many in the chapel will tell you, is the opposite of “rehabilitation.” For whereas state-sponsored rehabilitation can only change a man’s external behavior, transformation—which comes from a man’s own will or via the will of God within him—is said to fundamentally and irrevocably alter a man’s character.11 Arguably the dominant metaphor of evangelical prison ministry, transformation at Graterford comes foremost in a more secular iteration.12 Men like Oscar who repeatedly complete Monday night’s End Violence Program employ the language most influentially and ecumenically.13 And so, while the traditions of Abraham, the Apostle Paul, and the Caliph Omar each furnish an array of men radically reordered, here it is the prisoner Malcolm X, who, for the inner-directedness of his self-refashioning, is transformation’s patron saint.14

At the aisle’s source, John, one of two prominent Protestants deputized to supervise the study, moves in from the rolling cart of Bibles on which he’s been leaning and gestures toward the blue who has been preaching. “How are we looking at him right now?” John leadingly asks the assembled men.

“Like he’s stepping out on faith,” someone says.

“But how would the parole board look at him?”

With suspicion, says the silence. I know from Keita that the last time John was denied parole—it was his ninth rejection, for a sex crime of some sort—he left with the impression that his earnest testimony to the power of the Lord had roundly alienated the board members.

John continues: “But he’s got to see himself as God looks at him. Because God loves us. Because where is truth?”

Silence.

“Where is truth?” John repeats.

“In the Word?” the preacher responds tentatively.

“No,” John corrects him. “It’s in the pudding. The proof is in the pudding.” That is, to one day convince the suspicious, words are only the first step. Actions are what count. Among the oft-cited good news, however, is this: If a guy can live righteously in this crazy place, then he’ll surely be able to do it back on the street.

John commends the guys for coming out this morning and begs them not to give up on their fellow prisoners. He says, “You might hear ‘That’s the white man’s religion!’ or ‘That’s what my grandmother used to tell me!’ But remember for yourself, and remind them as well that ‘God has a purpose for you.’”

* * *

Jack, Papa, Mike Callahan, and Father Gorski are seated in the bowl of the ladle-shaped Catholic office. Like Omar, Papa commonly hangs out over here, making me think of the Catholic office as, among other things, the place where, once they can no longer keep up, the elderly black chapel workers are put out to pasture. Mike is the other Catholic office worker. Rarely venturing outside the Catholic office, Mike sits at his desk with his Daily News, listening to public radio and goading his colleague Jack into states of increasing agitation. Father Gorski is the Catholic chaplain. Mustached and soul-patched, as well as collared, the early-forties Gorski lives in a parish house in nearby Pottstown, his hometown. The youngest of the chaplains, and the most sardonic, Gorski is also the only political conservative among them.

Jack begs me over with a wave.

I congratulate him on yesterday’s confirmation of Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court. In spite of the direct and, one has to assume, unfavorable history many here have with that former Third Circuit judge, I figure a political conservative like Jack should be enthused.

“Oh,” Jack says with a despondent wave of the hand, “it doesn’t make much of a difference as long as the court’s still full of wacko liberals.”

Jack hands me the book he mentioned yesterday and directs my attention to his right where today’s Daily News is opened to a photo of the Philly district attorney Lynne Abraham.

“Look how manly she is,” Jack instructs me. “That reminds me,” he perks up. “I’ve been meaning to ask you: How come Democratic women are so manly-looking?”

“Who else?” I ask.

“Well, Janet Reno,” Father Gorski pipes in. This I concede.

“You know,” Jack says, pursuing his hypothesis, “as a general rule, Democrats are uglier than Republicans. I mean, look at Ted Kennedy.”

The resort to absurdist vitriol suggests that Jack is too lazy to play today for real. Largely, I have only myself to blame for the pattern of shoddy discourse I solicit from the Catholic side. One day, a few months in, I responded to a run-of-the-mill expression of revulsion about gay marriage with an impassioned defense of gay rights as a species of civil rights. The analogy proved little match for the “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” party line, and set an excruciatingly static agenda for weeks to come. While we eventually got over that ideological hump, the news cycle is always good for another.

* * *

Sayyid has his head buried in his translation. Kazi is reading his textbook for this afternoon’s class. A peppering of nosy pokes reveals that Keita, Baumgartner, and the Imam are each engaged in one-on-one counsel in their respective offices. The only office conversation to speak of consists of Brian explaining the implications of Collins to Teddy, though the term conversation is something of a stretch. Engaged with the case’s finer points, Brian is breathlessly coming at Teddy, who, for his part, is listening intently, in search of anything that might possibly be interpreted along the lines of “and so therefore a reversal is in the bag” or “so tell your lady that you’ll be home soon”—sentiments for which Brian finds little precedent in the case law, as he submits to you. When Brian finally takes a breath, Teddy asks him if he’s got an extra copy for him. Brian says he’s on it.

I ask Sayyid what precisely he’s working on. “A tafsir of Al-Asur,” he says. “Al-Asur?” I ask. “Yeah,” he says, “it’s about time.” I perk up, eager to explore the resonances of a Qur’anic commentary on time for one doing time. More than willing to humor me, Sayyid explains that the author Sa’di is emphasizing the indispensable nature of four things to a Muslim. They are: (1) belief in Allah; (2) knowledge; (3) righteous action … at which point I begin to fall behind. I ask Sayyid to slow down, and he starts again, but the list is distractingly full of nuance, and the third and fourth elements each boast a number of dependent clauses that somehow refer back to the first two principles. Finding it too complicated for a quick fix, I tell Sayyid to forget it and let him get back to his work. With a good-natured titter, he promises to break it down for me this afternoon. For now, he needs to get the translation done so he can get the book back to Mubdi—an old Warith Deen head—who’s been grumbling about wanting it back.

In spite of their doctrinal differences ideologically, Sayyid is the star pupil in Mubdi’s Wednesday-night Arabic class.15

* * *

Across the hall, in the ten-square-foot box known as the “conference room,” which is used primarily as a rehearsal space by the chapel’s musical groups, four musicians—Al, Oscar, Santana, and a fourth guy—are discussing the challenges of trying to make it on the street following a lengthy prison sentence. A South Philly black Puerto Rican in his late fifties, Santana works in the chapel, directs the Sunday Choir, and, in Baumgartner’s schooled estimation, possesses the chapel’s most beautiful singing voice. When at the Veterans Day service I finally got to hear him do “Love Lift Us Up Where We Belong,” Baumgartner sidled over to me and said, “I’ve left express instructions for Santana to sing this at my funeral.”16

A gentle-seeming soul, Santana has been, since his return from the hole at summer’s end, irritable and weary. As hearsay has it, the trip to the hole and subsequent foul mood both stem from Santana’s mounting debts, which sent him away for his own protection and forced him to kick his drug habit cold turkey. In flusher days, Santana would offer me insights. “I’ve been told no so many times it just rolls off me like water. I know that if I stop trying, I’ll die.” Sometimes perseverance finds its mark. “This is what you should be writing about!” he shouted in my direction one day from the back of the chapel, waving a wristwatch from his outstretched hand that an erstwhile Catholic regular had just given him, presumably to offset a debt. Santana is of the school that prison is little more than a microcosm of society at large. Just as Mamduh often quotes Dostoyevsky as saying, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons,” Santana observes that “anything you want to know about what’s going on in this jail, just look at your society. You’ll see it. You can’t miss it. The only thing missing is the physical building.”17

From behind the drum kit, the fourth guy, whom I know only by sight, is recalling a time from his childhood when a friend of his mother’s got out of prison and was struggling to make it. From what he remembers, the guy had quite a hard go of it.

Oscar feels what the drummer is talking about. Sometimes, it’s the little things that freak guys out, he says, like seeing dogs and cats.

Santana scoffs at this ridiculous empathy. He’s sorry, he says. While he’s happy to acknowledge the difficulties that go with the territory, he hasn’t got any time for the bellyaching. “Of course it’s hard,” he snaps. “But what I wouldn’t give for a shot! And the guys who do get the shot? They just wanna come back and complain about how hard it is! I mean, please.”

“Yeah, that’s true,” Al says. “But it’s like my lady tells me. It ain’t nothing like how it used to be on the street. It’s a different world out there now than the one we used to know, she say. And worse. Meaner. People won’t even cross the street to piss on you if you on fire. And then you supposed to make it out there after being shut in for so long?” After a pause, Al continues. “That’s why you need a real system of halfway houses, whether a guy is getting out on parole or maxing out … to help a guy adjust. It’s like back on the outside when I used to buy fish. When you go to buy a fish at the fish store, they give it to you in a bag of water from out of the tank where it was living. And when you get home, you take the fish in the bag and put the bag in your fish tank. And then the water inside the bag adjusts to the new temperature, gradual-like, and then only after it’s been in there for a while do you open up the bag and let him out into the tank. That gives the fish the chance to adjust to its new environment. If you just open the bag as soon as you get home and drop the fish in, it would die of shock.”

A St. Dismas regular pokes his head in the door to let Al know it’s time for Communion. Al hauls himself up out of his chair and follows the guy across the hall. I stand outside the open classroom door and listen to the song that accompanies the receipt of the sacrament. Few of the voices are particularly refined, or even in key, for that matter. Nonetheless, the song never fails to make the back of my neck tingle.

Let us break bread together on our knees

Let us break bread together on our knees

When I fall down on my knees

With my face to the rising sun

O Lord have mercy on me

I listen in together with an obese Latino dwarf who lives on the new side, floats between various chapel rituals, and who explains, when I ask him why he’s not inside, that he’s not prepared to take Communion yet. Saying that I probably wonder why I haven’t seen him around lately, he explains that he’s fresh from two months in the hole.

“Seems like a long time,” I say.

“No, that ain’t nothing,” he says. Once he spent eleven months in the hole. That was back when he first fell, though. And it had been for his own good, ’cause when he first fell he’d been hearing voices that told him what to do. He’d even gotten to thinking that he was God, if I can believe that.

Let us drink wine together on our knees

Let us drink wine together on our knees

When I fall down on my knees

With my face to the rising sun

O Lord have mercy on me

But they got him on the right meds now.

“That’s good,” I say. As I know from experience, I tell him, meds can save your life.

He hates taking them, he says. This is no surprise. While fifteen percent of Graterford’s prisoners are prescribed psychotropic medication, pharmacology is commonly disparaged as mind control.18 So he just takes little bits of them, to sleep, he explains. You know, if he took everything they prescribed him he’d be a zombie. Plus, he saw in the media how they cause diabetes.

I encourage him to stay with it, that life is hard enough as it is. He knows, he says, and he will. But, he adds, it’s not the meds that saved him. What saved him was this—he pats his Bible.

Let us praise God together on our knees

Let us praise God together on our knees

When I fall down on my knees

With my face to the rising sun

O Lord have mercy on me19

“Can I ask you a question?”

I look up from my notes to find a man whose unkempt appearance and coarse manner suggest shaky mental health.

“Sure,” I say. “But first tell me, who are you?” He gives me his name, explains that he’s been back inside for six months and has been a St. Dismas regular since then. He saw me in there this morning and he’s been dying to ask me a question. Outside, he worked for a caterer. They worked a lot of Jewish functions and he’s been trying to figure something out.

“Shoot,” I say.

“Why is it that Jews drink so much at weddings and bar mitzvahs?”

“Because they find it difficult to deal with their families when they’re sober?” I suggest with the pop-psychoanalytic common sense common to where I’m from. Not translating, he gives me back empty eyes. “How could you tell I was Jewish?”

“I can just tell,” he says, and waits for a better answer.

I shrug off the failure of my first effort and give it another shot, delivering a clipped series of non sequiturs on how there is no prohibition against drinking in Judaism, how there are even certain holidays, Passover, for example, and Purim, on which you read the Book of Esther—he nods in recognition—when one is obligated to drink. His stare remains vacant. I fire off a few overintellectualized nuggets about how Jews aren’t traditionally prone to alcoholism and some nonsense about how “drinking levels are cultural”—whatever the hell that means. Still no register.

Out of tricks, I go Socratic. “Are these bars cash bars or open bars?”

“Open bars,” he says.

“Okay,” I say. “And how do you act when there’s an open bar?”

“I drink,” he says.

“Do you drink a lot?” I ask.

“You bet,” he says with a blustering exhale.

“Well, there you go!” I say, and turn back to my notes.20

* * *

In the back of the chapel, Sal is shelving the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ songbooks on their cart, flattening their tops and pressing their spines flush. I ask him how it went this morning. “Always beautiful,” he says. With his characteristic combination of aggression and concern, Sal makes a crack about how tough it must be for me out on the street. I play along, complaining about what a drag freedom is. Good-naturedly, he pantomimes slitting my throat. I explain what I’m up to this week.

Sal reiterates what he told me one long summer evening in Baumgartner’s office. In jail, he says, there just aren’t too many things a man can choose for himself. So in those few realms where one has any freedom, exercising that freedom becomes very, very important.

Apologizing for my nonattendance this morning, I ask Sal if he’d be willing to detail for me what they did. They did a Watchtower Bible study, he says, and they learned about the workings of the Jehovah’s Witness organization. He says he’ll write me up an outline.

As promised, tomorrow Jack will hand me a sealed envelope, in which I will find a copy of the current Watchtower and a double-sided handwritten page. On the top it will read: “Joshua, Hope this helps. Sal.”

At the heart of the itemized account, Sal will detail how the Witnesses read a Watchtower study article, “Now Is the Time for Decisive Action,” whose title comes from First Kings and which takes as its theme Elijah’s challenge to the Nation of Israel: “How long will you be limping upon two different opinions?”21

Sal’s meticulous précis will capture the tenor of the Witnesses’ meetings, the bureaucratic flavor of their biblical urgency, their catechistic regimentation. Watchtower essays read like grammar school exams in reading comprehension. Every question has a correct answer, which the reader must locate in the article, which has been peppered with scriptural proof. As examples:

Question: “What great apostasy did the Bible foretell, and how has that prophecy been fulfilled?”

Answer: Just as in biblical times, the worshippers of Baal were eradicated, so too will the “false religion” practiced by most Christians today be wiped out in the great tribulation fast approaching.

“What must we do to survive God’s day of judgment?”

We must get off the fence and “act decisively now”! We must “take decisive action and zealously work toward the goal of becoming dedicated, baptized worshippers of Jehovah.”

Back in the summer, I pressed Sal on this brand of scriptural certitude. Don’t biblical passages at times possess multiple possible interpretations? I asked. No, he said, there are multiple translations of the Bible, which reflect the multitude of vantage points born of people’s varied experiences, but there is only one interpretation because interpretation belongs to God. “Let the Bible do it itself,” he counseled. “We cannot interpret God’s Word, because he already did it for us.” And those who believe Scripture to say something different? “They ignore the proof,” Sal said. “They hear what they want to hear.”

It is for me a challenging position. As I was taught back in Jewish day school, those texts that merit studying—the sacred ones, if you like—drive irrepressibly in the direction of openness. The Torah may be the perfect Word of God, but its verbal economy demands earnest interpretive labors. As was true in the Garden then, where man gave names to all the animals, also in the realm of Scripture are humans tasked with completing creation. Which, given the depth ascribed to these texts by the rabbinical tradition, means the obligation to never cease discussion.22 In addition to the vital pleasures afforded, this attitude toward scriptural interpretation yields—I tend to think—at least one crucial ethical principle, that being: Thou shalt presume no monopoly over the Truth.

Which is all well and good, Sal might say, were not the final judgment soon at hand and the fate of humankind teetering in the balance. With such stakes, dillydallying in the wondrousness of the text is a luxury easily sacrificed. Quite simply, an erroneous interpretation will land you on the wrong side of eternity. One must act decisively now.

“Acting decisively now” means spreading the true religion to those who otherwise will be consumed in the fire. It means going cell to cell and passing out literature, even though such proselytizing is a violation of the rules and could, in theory, land you in the hole. It means bearing witness to every soul you come across, a Jewish skeptic no less so than anyone else. It means giving this skeptic, shortly after first making his acquaintance, a seven-page single-spaced letter that you’d sent to all but three of your graduating high school classmates in response to a print of the twenty-fifth-reunion picture that one of them anonymously sent you—a letter in which you apologize for your history of violence, an ugly character trait of which some of them were undoubtedly on the receiving end, and which culminated in your murder of an off-duty cop. But true to the cliché that there are no atheists in foxholes, you will say that in prison you have found a way to live other than selfishly, and though you have little hope of ever getting out, you believe with all your heart that a wonderful future awaits you. But in the meantime, you will say, oversight from God does not come without cost. It involves, rather, the tremendous responsibility of letting each and every one know about the coming Armageddon and reminding them of how in the Sermon on the Mount as it appears in Matthew, Jesus speaks of the broad road and the narrow road, and how on the broad road walk the spiritually indifferent, the misled, and those who do not know Jehovah, and that that broad road leads to everlasting destruction. But there is another road, a narrow road, on which walk only a few. These, you will explain, are the Jehovah’s Witnesses. And you will say how it doesn’t matter who you are or what you have done, for like the prostitute who cries at Jesus’ feet, in the might of Jesus and Jehovah even the greatest of sinners may also find forgiveness.

* * *

Baraka is discussing the ethics of war with Vic the heathen. Yesterday, the professor, a moral philosopher whom they generally speak of with reverence, outed himself as a pacifist. To these two veterans, it is an asinine position. Baraka says something vague about “just blowing them all up.” Then, staring at me for effect, he adds, “Just kidding.”

“What?” I ask. “You think I’m going to submit an unsolicited note to the Clemency Board?”

“Be careful,” Vic cautions. “We’re both lifers”—he nods at Baraka—“both former Marines. It doesn’t get closer than that.”

“But what about our shared whiteness?” I appeal to Vic. “Doesn’t that mean anything anymore?”

“Maybe fifty years ago, when we were wearing sheets,” Vic says, laughing. “Now, not so much.”

A call for Baraka comes from the Imam’s office, and Baraka follows after. Vic points at me, stopping as if trying to remember something he had wanted to tell me. “Oh yeah,” he says, “Princeton came up in class yesterday.”

“Why?” I ask. “Walzer?” I figure that if they’re talking about the ethics of war, they’re probably talking about the political philosopher Michael Walzer, who is at the Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein’s old haunt.

“Yeah, that’s it,” he says.

I explain the difference between the university and the Institute, how the folks at the Institute get paid simply for being who they are and don’t have to do anything for it.

“Like you,” Vic says, “getting paid for nothing.” Vic is referring back to my explanation of how in my department, funding is not dependent on teaching.

“No, better than me,” I say. “They’re not beholden to anyone.” Back from the Imam’s office, Baraka flips out in my general direction.

“No, they’re not beholden to anyone,” he says, cocking his forehead to the right. “They’re just called up now and again by the NSA to produce white papers, which they dutifully provide without having to be asked twice. They’re all patriots, after all.”

At “patriots,” Vic issues forth an impromptu Sieg Heil! We argue about this a while. I say that while I appreciate Baraka’s point about the various levels of beholdenness, if there exists a single bastion of freethinking in this country—where knowledge, though not produced in an ideological vacuum, is, at the very least, produced with minimal procedural fetter—it would be a place like the Institute. Baraka rolls his eyes as if I’m saying that our great nation is a place where everyone is born free and equal and rises and falls solely on the basis of merit. He takes his pad out of his breast pocket and jots something down.

Soon he and Teddy head for the blocks. “Look, all I want to say,” Baraka says, continuing a conversation that I missed, “is that, contrary to what many guys around here say, death is not life, death is death.”

“No,” Teddy objects with equal vehemence. “Death is life because to live you must die every day.”

“No,” Baraka repeats. “Death is the opposite of life. Death is death, and it’s final.”

* * *

After lunch, Father Gorski brings Keita back a couple of staff dining hall apples and the Imam and I follow along. Though Keita’s office, following lunch, is usually a sleepy venue, today things get absurd fast. Gorski berates Keita for having bided his time until his wife, Martha, left for her annual Africa trip before springing into action and putting her cat to sleep. Keita squeals coincidence, but Gorski knows better.

Behind Keita’s desk, a colored-pencil drawing of eighties TV puppet and camp icon Alf spits forth a dialogue box reading “Got cat?”—a reference, if I recall correctly, to the idiosyncratic alien’s preferred cuisine.

I ask Keita whether the cat killers let him take the carcass home so he could eat it.

“Maybe in Africa,” Keita says, “but not here among the white man. Here it is, unfortunately, against the law.”

Passing my eyes to the far wall, I notice that a full year past its expiration date, Keita’s single-paneled Shrek wall calendar has finally been taken down. “What happened to Shrek?” I ask about the animated ogre.

“Yes,” Keita solemnly says, “it was time to retire him.” He will always love Shrek, though, he says, mostly for how he cooks mice rotisserie style. It reminds him of how back in Africa he would eat cave bats in the same way. Adopting a wistful air, Keita recounts how when he was little they would rise before dawn, climb into the hills, and watch the sunrise from the mouth of a big cave. There they would wait. Eventually, the bats would appear, fat from a night out preying on mosquitoes, and the hunters would crack their whips and smack them from the air. Then they would roast them on spits, just like in Shrek.

The Imam is horrified. No, he groans. In his native Nigeria they eat pigeons, but never bats.

Feigning incredulity at such prudishness, Keita reminds the Imam that back when they were wandering in the desert, the Hebrews ate bats as well. He points at me: “Your grandparents, or great-grandparents, or great-great-grandparents—they were bat-eaters too.”

“Says us. But my people only converted with the Khazars.” I’m playing with the trope common among the Black Nationalist religions that the biblical Israelites have no genealogical connection to today’s Jews. “The true Israelites were Africans.”23

Still chewing on the winged rodents’ culinary potential, Gorski muses that bat wings must be light and crispy, an assumption that Keita confirms.

Baumgartner arrives with a stack of mail in hand, which he distributes, piece by piece. Baumgartner points out that he, Keita, and Gorski each received an identically worded communiqué from a freshly blued parole violator, pleading with them to please do something to stop his wife from divorcing him. Their collective response is a cross between bemusement and scorn. They’ve seen it too many times before, and this blue they don’t even know. All they can do is laugh mirthlessly, substituting for their inefficacy the consolation of shared frustration.

The chaplains are in a bind. Because they are trained in a caring profession, they are predisposed to distinguish themselves from the administration’s custody-based approach, in which prisoners alternatively appear as dangerous criminals or as tedious babies, requiring, in either case, the identical regimen of callous discipline. While the chaplain’s aspiration to treat the prisoners as men is generally quite practicable, a conspiracy of factors nonetheless reinforces the prison’s dehumanizing operating logic. From above, they must placate the custody hierarchy for whom accommodation spells weakness and empathy is a slippery slope. From below, they must fend off a population squeezed between infantilization and deprivation, and prone to crisis. In a facility of 3,500, this means a constant flow of tugging, cajoling, game-playing. Exacerbating matters, the chaplains are one of only two classes of employee in the prisoners’ wings of the jail with direct phone lines to the outside, resulting in a parade of men pleading, on account of a family crisis, to please place a call for them, just this one time.24 Periodically burned and, before long, burned out, the chaplains come to deflect, to indulge in gallows humor, and to adopt as a default condition a posture of sardonic remove, which in a roundabout way brings them into proper alignment with—as Father Gorski puts it—“the World of No!” in which the prisoners live, a world antithetical in ethos to the affirmative mode to which the chaplains consider themselves vocationally attuned. But such is the job.

As they commiserate over the letter, the Imam relates a story about a guy who came into his office last week frantic to get married before his child is born. He laughs. From a Muslim perspective, he complains, the child will be considered as born out of wedlock regardless, and anyway, he doesn’t even perform marriages!

The Imam’s anecdote returns Keita to Africa, calling to mind how his brother had so many girlfriends that in their village today, there are dozens of kids running around who look just like him.

“That’s what you tell Martha, anyway,” Baumgartner says.

Keita explains to me that his brother, as the village imam, gets up before dawn to make prayer, and when that’s taken care of, he stops by his girlfriend’s house.

“No!” the Imam hollers.

Surely, I suggest, the predawn tryst can only be a Muslim contribution to illicit sexuality, since without having to get up before the sun to pray, a Jewish or Christian man would surely rather stay in bed.

I excuse myself for Baumgartner’s bathroom. When I emerge the prisoners are back, but Baumgartner pulls me aside.

“There is general concern that when you write your dissertation you’re going to say that the chaplains just sit around and talk about sex.”

* * *

I take up my spot in the back of the chapel and wait for the action to come to me, which it does presently in the form of Gabril, or, as most everybody calls him, Sugar. Gabril is stylish, and not just because of his Italian glasses and the sharp beard that he has pulled to a point with a razor blade. Rather, Gabril’s whole way of being in the world is stylish, a manner heightened since his picture recently appeared in the New York Times in an article about middleweight champion Bernard Hopkins. Hopkins spent half his twenties in Graterford, where, per the old Hollywood formula, Gabril taught him to fight—this back when the jail had a traveling boxing team. According to the new formula, there’s now talk of a movie, a project which, according to Gabril, Hopkins has vowed to postpone until his old mentor is free. Like Oscar, Gabril is serving life for a crime committed as a juvenile.

Gabril peppers his conversation with various sayings of the Prophet, in English mostly. His favorite, which he repeats like a mantra, instructs the Muslim to “Take care of these five before you take care of the other five: health before sickness, youth before old age, wealth before poverty, work before leisure, and living before death.”25 Of late, Gabril has been brokering conversations with some of the more influential yet lower-profile Muslims from the Salafi side.

“What’s up?” Gabril says.

“Same old,” I say.

Gabril is decked out in his browns’ winter wear, featuring a burgundy corduroy coat and an even purpler knit hat, both of which fit as if tailor-made. I compliment him on the coat.

“Yeah, these,” he says, dragging the backs of his fingertips along the wales. “This ain’t nothing compared to what I would wear on the outside. I’d be wearing a fine coat, you can be sure of that, with my car keys in this pocket right here.” He pats his breast. He seems preoccupied and turns to go, but then reconsiders.

Gabril looks at me with his milky fighter’s eyes. “Have you heard the rumor?” he asks.

“What rumor?” I bite.

“Well, not the rumor,” he corrects himself, “but the hearsay. Seventy-five percent of which, in my experience, turns out to be true.”

“What?”

“Sayyid is in detention.”

“What?” I stammer. “What’s going on?”

“Unclear, unclear,” he says. “I was hoping to come down here and find out.”

“Well, let me know what you turn up,” I say. He will, he says, though we both know that for want of opportunity or motive he probably won’t. With an Assalamu alaikum, Gabril leaves me with this troubling revelation.

If Sayyid is in detention, then he is likely headed to what is known to all but the administration as “the hole.” Though men in the chapel can emphasize the hole’s positive aspects, speaking of it as a time apart where one can hone his spiritual discipline, refine his focus, and reemerge recharged, being locked up in a two-man cell for twenty-three hours a day is a profoundly upsetting and arduous undertaking. Depending on what Sayyid is accused of, he could be looking at weeks or even months there. If found guilty of a violation, he could lose his job and his place in the Villanova Program. If things break bad, he could easily find himself shipped to another institution.

Even as I worry about Sayyid’s welfare, I can’t help but feel in Gabril’s probing presence the excitement that accompanies the periodic eruptions of violence here—whether that violence be spontaneous and hot like last winter’s, when a misprocessed new prisoner sent a guard to the hospital via medivac, or brutally clinical like today’s.26

* * *

Teddy bursts in to find Baraka staring down the typewriter from over his lowered lenses.

“I just can’t believe that you don’t believe in the afterlife,” he grumbles.

“Death is death,” Baraka says, his scrunched brow unlifted.

Vic, who was inventorying bottles in the cleaning-supply locker, is thumbing his way through an old New Yorker. He says he’s got a question for me. I tell him I’ve got a question for him.

“You first,” he says.

“Okay,” I say, trying to be an asshole. “Shouldn’t you be cleaning?”

Vic gives me a cock-headed furrow. “No,” he says. “I cleaned up this morning before you even came in.” On his turn, Vic asks me about “the deal with Zionism,” so I deliver a spiel about the movement’s ideological drift from nineteenth-century socialism to twenty-first-century ultraorthodoxy.27

Scowling, Teddy announces that he’s “bringing you both up on charges.”

“For being white?” I say, fighting absurdity with absurdity. “If so, I’m innocent.”

“No, not for being white—that’s not your fault. But for invading the ghetto. Y’all gonna drive the prices up and pretty soon me and Kaz and Al ain’t even gonna be able to afford to sit in here!”

And with that, Teddy leaves.

* * *

Below the chapel floor, pressure slowly builds as an ancient boiler turns water back to steam and pushes it through the closed loop that runs, when it runs, to every last corner of the jail. Absent the hum and clack of this hidden machinery, the chapel is silent. The winter sun casts long shadows from the pews’ leftward edges, and shines on Al, who, alone in the chapel, is priming the PA system for tonight.

In the darkened conference room, meanwhile, four black men are watching a video of celebrity preacher T. D. Jakes.28 Quiet for now, they will periodically erupt with “Yes, sir!” and “Amen,” and when prompted they will lay their hands on one another. I’m looking for Charles, who’s been missing since I’ve been back.

Unlike most of my interlocutors, Charles is slightly my junior. In addition to video ministry, the religiously eclectic Charles is a regular at the Sunday service, a student in Wednesday morning’s Education for Ministry class, and even an occasional presence at the Native American smudging ceremony. Largely unschooled, Charles has a penetrating if not somewhat perverse intellect and does not shy away from provocative positions. He has openly condemned as “delusional” the sort of prayer that enables a guy to sit back and wait for God to intervene. He spoke too of “‘these dudes’ syndrome”: how guys are always talking shit about other people, saying how crazy or pathetic “these dudes” are, whoever these dudes happen to be. But, as Charles sees it, “We are these dudes,” and as such, “failures at life.”

“I don’t want to disillusion you,” Charles said to me once, “but a lot of these dudes just come to the chapel for something to do.” I was in no way disillusioned. For an anthropologist of religion for whom religious ritual, at root, is human activity, Charles’s insight made all the sense in the world. Put simply, a Graterford prisoner who is looking to grow intellectually or spiritually may read in his cell, go to the school, or go to the chapel. The Graterford prisoner who wants to hang out with others may loiter on the block, try the yard, or come down to the chapel. Of course “these dudes” come to the chapel “for something to do.” For Charles’s peers, however, for whom religious sincerity is paramount, observations of this sort can only be taken personally. Consequently, the same live mind that commonly thrills me seems to render Charles a chapel pariah.

If varied, Charles’s attendance in the chapel is also sporadic. As an out-of-state lifer, Charles is doing his time alone, and sometimes—I get the impression—he can’t quite cope. Which is why, peering through the conference room window, I’m disappointed but not entirely surprised to discover that Charles is nowhere to be found.

* * *

Officer Bird’s glasses are still tinted from the outdoor light.

“What’s up with your hair?” he asks me. I pat it down. Solely by virtue of neglect, my frizzy head has grown into something of a spectacle. I marvel with Bird at the madness of last night’s ice storm, which left my Philly neighborhood a fairy tale and the highway a disaster.

“It’s a sign of the times,” Bird says.

A few minutes past 2:00, Al and Santana pass through the vestibule on their way back to the blocks. Apropos of the weather, I ask Santana if he’s been outside today.

“You crazy?” he snipes at me. “Why don’t you go out there?”

Baraka passes through and I pose for him the same question. He shakes his head. “Nah, nah. It’s cold,” he says. He then adds matter-of-factly, “We don’t go outside.”

“When’s the last time you went outside?” I ask.

Another shoulder shrug ends the exchange. I don’t think to ask Baraka who “we” is.

* * *

Half in search of the skinny on Sayyid, I venture back to the annex to check out who’s shown up for Talim class, as it is designated on the weekly activities schedule but by no one else. In practice, Talim (talim is Arabic for “learning”) is little more than unstructured time during which Muslims are allowed to congregate in the annex.

By the chest-high partition of flowered terra-cotta blocks that cordons off the shoe area from the rest of the annex, Mamduh is leading his small Arabic class. Behind these four, along the annex’s eastern wall, two old men sit with books in their laps. Otherwise, the austere cinder-block cube is empty.

Early in my fieldwork, Tuesday afternoon’s sparse attendance posed the chapel’s most manifest mystery: Why, in a 3,500-man facility where a quarter identify as Muslims, does one find, during one of the two weekly windows when they are allowed unstructured time in the chapel, only a handful of men exercising the privilege?

Like today, Mamduh was usually one of the few Muslims around. He had a lot of questions for me back then, about where I’d been, what I’d read, who I knew, and how I knew my Arabic. He wanted my editorial help, too, on a manuscript he was completing for a correspondence degree in Islamic learning, a comprehensive guide to the “customs of nature” (sunan al-fitra) through which the devout Muslim’s body may be restored to the state of purity in which it was created. Expressive of both his puritanical disposition and his encyclopedic scholarly style, the manuscript consisted of three-to-four-page chapters on subjects such as bathing, hair care, beard trimming, cuticle maintenance, and tooth care, findings resourcefully culled from a hodgepodge of sources ranging from medieval commentaries and modern religious tracts to commercial promotional material. A tract for insiders, each chapter concluded with a definitive prescription, or in cases where disputes resisted ironing out, with the humble acknowledgment that Allah knows best.29

In return, what Mamduh had for me was information, clues that pointed me toward the missing Muslims, which in turn helped me piece together Graterford’s history more generally. Mamduh spoke with the affect of discretion—huddling close over the partition, dropping, at critical moments, his hoarse voice to a near whisper—but as time went on, he ceased to mask his partisanships and resentments. Mostly Mamduh was frustrated, frustrated with the intellectual lifelessness of his community, how unserious people had become, and how little support his community received from the Imam—a man whose observance of Islam he saw as deviating wildly from that of the Prophet. While I bristled against Mamduh’s religious absolutism and came to understand his reputation among the chaplains as a malcontent, his facts tended to check out. His general air of lamentation didn’t seem far off, either. For while I’m attuned to the fact that one of the moods that religion tends to foster is the preemptive mourning of its own passing, I took at face value the cataclysmic communal loss Mamduh described, and sensed that his bitterness, though partially misdirected, was in no way disproportionate to the devastation wrought by “the raid.”

* * *

As recently as the summer of 1995, the chapel was awash in Muslim activities, which took place mostly in the basement. The jail had no fewer than ten Muslim-identified sects back then, but the two most prominent were Masjid Warith Deen Muhammad and Masjid Sajdah.30 Both of these downstairs mosques—the more progressive Warith Deen and the more traditionalist Sajdah—were vibrant community centers. Each mosque convened daily for three of the five prayers and for a variety of self-administered programs. The two masajid had expansive libraries, too, where, in an era of residual openness, Graterford residents were allowed, with few restrictions. On Fridays, each mosque’s Jum’ah service would draw hundreds of men, who, for the occasion, were allowed to dress in civilian clothes and invite in family and friends. Intellectually, spiritually, and socially it was a good time to be a Graterford Muslim.

Not all, however, was so wholesome. I’d been in the prison only a couple of weeks when I began to hear tell of a mythic figure—one more out of The Arabian Nights than HBO’s Oz—a giant with humongous hands who used to run the show downstairs back when the Muslims were down there. It was said that his viziers would bring him trays of food, that he had his own phone line with outside access through which he ran his criminal enterprises—prostitutes on the inside, drugs on the outside—and how nobody had a goddamn clue.

Reverend Baumgartner also told me about the former leader of Masjid Warith Deen Muhammad, Ameen Jabaar. Relating a legend that also made it to the news, he described how one day a group of guards had come downstairs to announce an evacuation drill. Everyone was instructed to leave. One hundred men refused to move. The COs cajoled, but the men stood firm. The COs didn’t generally go down there, and they didn’t know what to do. Eventually, Ameen was sent for. In the Philadelphia Inquirer’s version, Ameen is a genie. “He came over and waved his hand, and it was done.”31

Back then the administration’s reliance on prisoner leadership for the maintenance of social order was undisguised. But a decade into the crack epidemic, violent crime was up, conservative social theorists warned of a new generation of super-predators, and even Democratic politicians couldn’t be tough enough on crime.32

Corrections was the new master category, and control its linchpin. In institutions across the country, prisoners’ movements were restricted and surveillance was heightened. Educational and psychological resources were gutted. The nominal purpose of incarceration ceased to be about rehabilitating prisoners. Prisons were now for punishment.33

Meanwhile, as American industry rusted, “the prison industrial complex,” as activist Angela Davis dubbed it, boomed.34 During the 1980s, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania doubled its number of prisons, from five to ten, and in the nineties added eleven more.35 Like the spike in traffic that often follows new highway construction, Pennsylvania’s prison population skyrocketed as legislation and administrative adjustments raised mandatory minimums and restricted parole.36 At Graterford, the new-side cellblocks were constructed.37 A facility that in 1981 had a population of 1,900 men had nearly doubled in size.38

On January 17, 1995, Republican Tom Ridge was sworn in as Pennsylvania’s governor. Responding to a moral panic over the exploding crime rate, Ridge had run a law-and-order campaign, promising as governor tough new policies, like a three-strikes-you’re-out law and a streamlined death penalty process.39 As promised, changes were instituted system-wide and at Graterford in particular: newly sentenced prisoners were shipped as far from home as possible, forced to earn their way closer to their families with good time; and the lifers, some of whom had lived in the Outside Services Unit for a generation, were brought back inside the walls. Neither was the chapel exempt. On February 3, a policy in place since the mid-seventies guaranteeing the right of prisoners to convene their own religious services was revoked.40 Henceforth, no service or instruction would take place without a supervising chaplain or volunteer. And these were merely the tremors.

In his subsequent report to Pennsylvania’s Senate Judiciary Committee, Governor Ridge’s new secretary of corrections, Martin Horn, described the anarchy he had inherited. He explained how, at Graterford in particular, the liberal and humanitarian innovations of the 1970s, left unchecked for a quarter of a century, had festered. And Horn had taken it as his express mission to “sanitize this facility.”41

Yunus, a former Imam of Masjid Sajdah, remembers what happened next. It was a warm night for late October and he was lying in his cell, the 99-cell, which sits at the top step in the front of B Block. It was after the regular 9:00 p.m. lockdown and his window was open. From the main corridor, the sound of hollering, of a commotion, roused him from his bed. And then: “Police is here!” “Raid!”

State troopers and COs from across the system stormed into the jail, 650 men in all. Over the next seventy-two hours, each of the prison’s 3,490 inmates was strip-searched, and each of its 2,750 cells was ransacked.42 When the swarm finally receded, prisoners’ possessions were reportedly piled shoulder-high the full length of the cellblock. Casualties ran low and high. Nine employees were fired on the spot, and twenty-one prisoners, most of them community leaders and power players, were transferred, some across the state, and some, through a measure allowing states to trade their most dangerous, across the country. Among those shipped was Ameen, who, according to legend (and Baraka insists it is only that), was paraded away in nothing but handcuffs and underwear.43

The press trumpeted the size of this game. In its coverage on day two of the raid, the Daily News ran a feature on Ameen, entitled “Inmate Throne for a Loss; Prisoners’ ‘Kingdom’ Toppled.” Drawing no distinctions between Graterford’s various Muslim groups, the piece described how “the Iman [sic], or religious head of Graterford’s Muslim population,” and his battalion used religion as a cover for criminal activity. “As the religious services were going on in one room, a brothel was being run in another.”44

The Muslims’ sway was eminent. “‘If you don’t want no trouble, become a Muslim,’” the Daily News reported a Graterford-bound prisoner being told on the bus. “They’ll protect you ’cause the Muslims run the jail. That’s how come a lot of guys get religion when they go to prison.’” The article concluded on an up note: “But he remained a Christian.”45

When lockdown ended and the Muslims returned to the chapel for Jum’ah, they found the mosques ransacked. Soon thereafter they were informed that their days downstairs were numbered. A new era had dawned. Family and friends were banned, and civilian clothing was prohibited. For nine months following the raid, no volunteers were allowed in the jail. Graterford’s chaplains oversaw the larger services, and the gatherings of the smaller groups were suspended. The Muslims continued to meet downstairs, now under the supervision of the COs and Graterford’s first Muslim chaplain, who was hired on a contract basis.46

Of the two masajid, the traditionalist Masjid Sajdah was the more obstreperous. A lawsuit was filed. Avowing a decentralized democratic sensibility indigenous to American religion and Islam both, Sajdah opposed the DOC’s new concentration of religious authority. “O you who believe!” the Sajdah brief quoted the Qur’an. “Obey God and obey the Apostle, and those charged with authority among you.”47 For Sajdah, “among you” was proof that a DOC appointed imam would not suffice Islamically. Further support for this principle of local autonomy was found in a hadith, a saying of the Prophet: “No man must lead another in prayer where the latter has authority, or sit in his place of honor in his house, without prior permission.”48

The Sajdah plaintiffs made a strong case, but the climate was not what it once was. Relying on the guidelines laid out by the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), the DOC trumped Sajdah’s expansive reading of religious autonomy with an appeal to security. Making explicit mention of the mosques’ raised floors and drop ceilings, the DOC argued that these spaces were “conducive to hiding contraband, which can include weapons, money, and illegal drugs.” The DOC made no explicit claim about criminality on Sajdah’s part. Indeed, it acknowledged the masjid’s two-decade track record of clean behavior. However, because the equal protection clause requires that all groups be treated the same, this record was immaterial. Similarly, because allowing an inmate to occupy a leadership position affords him “a power base” from which to incite violence or conduct illegal activity, such positions were also, for security reasons, to be eliminated.

It is easy to imagine the forked resentment with which members of Masjid Sajdah greeted the DOC’s response brief and the resounding defeat it foretold. As it could only seem to them, the Warith Deen guys stepped out of line, the DOC retaliated, and Sajdah got caught in the crossfire.

Such was the poisonous environment into which the mild-mannered Nigerian émigré Namir Kaduna was thrown. To exacerbate matters, before becoming Graterford’s imam, Namir had provided the DOC an affidavit stating his understanding that there is no prohibition in Islam against being led in prayer by a government chaplain. Inevitably, the hostility only grew once Namir was on the ground. As Mamduh said, “When a chaplain threatens to give you a write-up”—a measure that could mean two additional years come parole time—“you know where he stands.”

While Baumgartner now sees “the Imam”—as most call him—as his “right-hand man,” he too initially presumed Namir to be a plant from the secretary’s office. Three candidates had been up for the job—the current contract chaplain, a second African-American, and Namir. When Baumgartner showed up for the interviews, the assistant secretary of corrections, Jeffrey Beard, pointed to Namir and told Baumgartner, “That’s our guy.”

The conspiracy, as it turned out, was somewhat different. As Baumgartner and other Pennsylvania prison chaplains figure it in retrospect, Namir’s hire was plainly a part of a DOC effort to replace the first wave of African-American contract Muslim chaplains with full-time ones from the Middle East and Africa. Thought of as being both apolitical and devoid of compromising ties to the neighborhood, the foreign chaplains were seen as less dangerous than their African-American counterparts, who, a generation later, still carried the revolutionary odor of Malcolm X. Still years away, of course, was 9/11.

Namir’s marching orders were to take Graterford’s divided Muslim community and make it one. It was a directive Namir wholeheartedly believed in. Why should Muslims who pray to the same God pray separately under the same roof? “Do you believe in Allah?” Namir asks would-be schismatics. “Do you believe in rasul Allah?”—that is, in the messenger of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad? If the answer to both questions is yes, then you are a Muslim and you can pray with all other Muslims the same as they do in Mecca. Or so the Imam continues to insist.

Not all have been equally obstinate. The Warith Deen elders, who tend to be politically savvier than their more absolutist counterparts, knew not to look a gift horse in the mouth. And so, opting for graciousness over contempt, it was Baraka, then a chapel janitor, who ended up the Imam’s clerk, with use of a desk in his office and access to his ear.

Ten years past, the raid is still an object of great passion and frequent discussion. In the ritualized recollections of prisoners as well as staff, it is generally derided as having been a wasteful and capricious exercise. Even the military-styled career DOC employee who began his new staff orientation with a half-hour retelling of the raid attested to the fact that the cache of drugs and knives paraded before the media consisted entirely of items seized beforehand.

Baumgartner isn’t over the raid, either. The chapel’s criminal excesses were a humiliating revelation; the DOC’s brutal response was destabilizing, as intended; and Baumgartner remains equal parts wary and resentful. Nonetheless, if pushed to say one way or another, Baumgartner figures that in aggregate, the net effect of the raid in the chapel has been a positive one, with the increased security and oversight leading to “more authentic” forms of worship.

In Graterford’s institutional memory, the raid is the pivot point between two periods: Before the Raid and After the Raid. Albeit belatedly and imperfectly, the raid yanked Graterford into the era of carceral control. In the ascendant regime of diminished opportunities and heightened restrictions, not all of the new measures seem excessive.49 Whereas prior to the raid, prisoner movements at Graterford consisted of simply throwing open the cellblock doors and flooding the prisoners into the main corridor, nowadays, work lines, activities, and yard are each moved in deliberate sequence. So whereas before the raid, drug deals and contract killings would take place right in the main corridor, such occurrences are now almost unthinkable. In 1995, Graterford had 102 reported inmate assaults, but by 1998 that number had fallen to thirty-two—though the vast majority of assaults still go unreported, just as they did before.50 And while prisoners, staff, and administrators all assert that anything one can get out on the street a guy can also find at Graterford, drugs are allegedly much harder to come by.

Meanwhile, the bygone era, characterized by Mamduh’s protégé, Nasir, as “TVish” for the grotesqueries of its purported realism, has become an object of considerable nostalgia. As one longtime female CO compared the present to those realer days: “Yeah, it’s safer now. More boring, but safer.” It was harder then, it is commonly said, but better. The new era is worse, not in spite of the increased safety, but precisely because of it. Doing time has gotten too easy, many older heads say. As Baraka put it, these days there’s “too much breathing room,” which keeps the young guys from committing themselves wholeheartedly to anything. “Back then,” he said, “there was no gap between what you said and what you did.”

“Then we had men here. We just have children in here now,” Santana said, complaining that the young guys treat their time like a vacation, just lying in their cells and watching TV. In the old days, it is said, the prisoners had a sense of unity, one that they would channel into strikes for better food and health care, but such actions could never take place now. By stick and carrot, the prison population has been broken down and atomized. Whereas once there was a system of block representatives and prisoners would employ the tools of organized labor as a counterweight to the administration, nowadays, according to the youthful president of the Graterford Branch NAACP, “if you try to stand together, they treat you with Thorazine.” Or, more likely, would-be agitators are simply shipped out, losing in the process the few privileges they enjoyed—their jobs, their activities, their stuff, and proximity to their downstate friends and family. Since, as Al put it, “He don’t know me and I don’t know him,” one has little trust his fellow prisoner won’t snitch. Unlike back in the day, now everyone just looks after himself.51

In such an environment, is it any wonder that the religiously inward Salafi Islam common to the former Masjid Sajdah crew has ascended while the activist Warith Deen brand of Islam has increasingly acquired the dull face of a historical artifact?

What was lost in the raid remains palpable in its absence. In Mamduh’s accounting, whereas Jum’ah downstairs used to draw in aggregate between 700 and 1,000 people, it’s now half that. Some guys study on the blocks, but if they try to do so in groups larger than six, the COs are supposed to break them up. According to Mamduh, many of the former Sajdah guys actively boycott the chapel. Everyone comes to Jum’ah because according to the Sunnah it’s obligatory, but that is all the legitimacy they are willing to lend to the man mistakenly honored, in their view, with the title of Imam. Others tell it differently. Chapel attendance is down, they say, not just for the Muslims but for everyone. Before the raid, the chapel provided a precious haven from the insanity common to the rest of the jail. Nowadays, increased security makes the need for a sanctuary somewhat less pressing.

For whatever reason, on Tuesday afternoon, with Talim on the program, I’m not at all surprised to find only five men in the annex. And so, in search of details about Sayyid’s detention, the annex seems unlikely to bare any secrets.

* * *

Teddy ambles up the center aisle and drops down in the front row of pews. I’m standing at the lectern at the foot of the altar, where I’ve been scribbling in the formerly empty chapel. It’s all I can do not to ask about Sayyid.

“You know,” Teddy says to me, “usually when someone starts at a new job, it takes them a while to figure things out, but you come in here, and right away…” Teddy trails off, his flattery unfinished. “What you doing, lurking back there?” he growls past me. I turn and find Baraka, who has materialized on the rear of the stage. He is helicoptering his arms in the widening circles that make up the concluding reps of his daily stretches. Teddy hops to his feet and closes in on Baraka. They trade a few words out of earshot and then wander over in my direction. As they come back into range I make out something about Sayyid being on L Block.

“How do you know?” I ask to blank stares. Thinking the problem to be an unidentified antecedent, I repeat: “How do you know Sayyid is on L?” Again, no answer. “How do you know?” I ask again as Teddy approaches me. Teddy leans into the mic stand at the foot of the stage, amps up his voice, and echoes, “Know? Know? Know?” With evident impatience, he cocks his head toward the security camera.

Baraka adds, “You forget that we are living in a police state here.”

“Shit,” I say. “Oops.” Silence.

Baraka smiles. “You never know if we’re joking, do you?”

“No,” I say, “but”—I echo his words back to him—“I proceed as if everything in here is real, or at the very least it better be treated that way.” Apparently, Teddy is not the only suck-up around here.

Teddy takes off. Meanwhile, as the next phase of his exercise regimen, Baraka starts walking a determined circuit between two rows of pews to my left. He thinks out loud about some projects he might undertake under the auspices of the newly launched Graterford chapter of the Villanova Alumni Association: a video to be shown on the in-house Graterford network, about domestic violence; a facilitation program for kids with incarcerated parents; a resource bulletin to be distributed in the visiting room that will inform family members of their rights. Having recently met a woman who’s offered to help, Baraka asks which option sounds appealing.

I say that she’ll likely be game for whichever. “Given your prominence,” I add, recalling Brian’s teasing from yesterday.

“What are you talking about? I’m not anybody,” Baraka says in the high-pitched tone that might just be his tell.

“That’s not what I hear,” I counter. “I hear that when you go down to the visiting room, four shorties carry you in a litter while a fifth walks alongside, feeding you chocolates.” Baraka indulges me with a wheeze. He continues to walk. I continue to write.

Baraka brings up his case. Last year, he tells me, his wife and daughter found previously undisclosed statements made by the state’s key witness, none of which makes any mention of him.

“So you’re claiming innocence?” I ask him. This I didn’t know.

“Innocence and Brady,” he says, referring to Brady v. Maryland, the 1963 Supreme Court case that established a prosecutor’s willful failure to turn over potentially exculpatory evidence as reversible error.52

In a direct disclosure atypical enough to make me wonder about his motivation, Baraka continues, filling in a number of details I hadn’t known. His 1974 conviction was based on eyewitness testimony alleging not that he was the shooter but only that he participated in a conspiracy to commit murder. And for this, life? It strikes me as odd, but I hold tight to my confusion. “Unfortunately,” Baraka says, “the guy with the hardest time proving his innocence is the guy who doesn’t know anything about the crime.” The first he saw of any of his alleged coconspirators was at his trial.

“Hmm,” I start, “so as easy as it is to allege conspiracy…”

“Is how difficult it is to unprove it,” Baraka finishes.

“So why you, Bar?” I ask. “Why did they put the frame on you?”

“Because a few weeks earlier I shot a cop,” he says. He adds derisively, “That is, according to them, I did.” This Baraka has told me before. As Baraka explains it, the charges were later dropped for lack of evidence. Nevertheless, I am momentarily curious enough to make another social misstep.

I ask: “So am I to believe that despite all your talk about putting something in somebody’s head”—Baraka’s preferred term for retaliatory assassination—“you never put anything in anybody’s head?”

Baraka’s laugh this time is not high-pitched. “You know, there are some things I will not answer.”

Clumsily I cover. “Well, you know, there are some things I won’t ask seriously.” We each let it drop.

Two older Muslims emerge from the annex. Baraka hails them in Arabic and they respond in kind. They turn and slowly edge their way toward the back of the chapel.

Baraka turns to me. “When you’re done here,” he says with assurance, “you can say that you met certain people.”

I don’t understand. “Isn’t that Abdullah Shah?” I ask, referring to a man who though a widely respected Warith Deen elder, is—as far as I’m aware—no more famous than that.

“Nah,” Baraka says, “that’s Rafiq.”

“Rafiq? Who’s that?”

“Rafiq?” he repeats. Nothing is triggered. He tries a Christian name, first and last. The name rings only the vaguest of bells. Baraka looks at me incredulously. Then it clicks. It’s the name of one of the men featured in a recent book that a couple of the younger guys turned me on to, which chronicles the rise and fall of Philadelphia’s Black Mafia. This guy was one of the ringleaders.53

Baraka jumps to a subsequent conclusion. He instructs me: “You have an obligation based on what you’ve seen to tell folks out there that some people are not what they are said to be.”

We watch the two hunched men slowly recede. “You know, those guys were both my lieutenants back in the FOI,” he says, referring to the Fruit of Islam, the Nation of Islam’s paramilitary order. With a look of pride and protectiveness, Baraka watches over the trudging old men as they leave the chapel behind.

From the volume of the quiet, we intuit that it’s time for Baraka to head out, too.

* * *

Teddy is in the process of leaving the chapel. Jutting out of his mesh commissary bag is an ostentatious brick of candy. The candy is surplus stock from Christmastime when the Brotherhood Jaycees, a youth service organization, distributed the sweets in the visiting room as part of their annual fundraiser. Now a month past, Teddy, the Jaycees’ secretary, is in the process of removing the remainder from its storage place in Keita’s office.54