no to naraba | If it becomes a moor |

uzura to narite | I will become a quail |

nakioramu | and cry. |

kari ni dani ya wa | Would you then come back, |

kimi wa kozaramu | even for a while, as a hunter? |

Moved by her reply, the man gave up the thought of leaving her.

The Road All Must Travel (125)

In the past, a man fell ill and felt that he would soon die.

tsui ni yuku | I had heard |

michi to wa kanete | there is a path |

kikishikado | that all must follow |

kinō kyō to wa | but didn’t think yesterday |

omowazarishi o | that I’d be going today … 124 |

[Introduction and translations by Jamie Newhard and Lewis Cook] | |

Sei Shōnagon (b. 965?) was the daughter of Kiyohara no Motosuke, a noted waka poet and one of the editors of the Gosenshū, the second imperial waka anthology. (The Sei in Sei Shōnagon’s name comes from the Sino-Japanese reading for the Kiyo in Kiyohara.) Around 981, Sei Shōnagon married Tachibana no Norimitsu, the first son of the noted Tachibana family, but after she bore him a child the next year, they were separated.

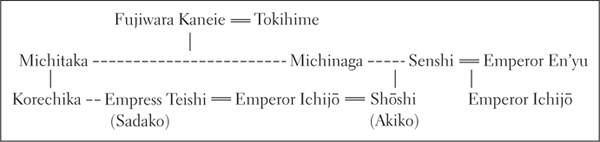

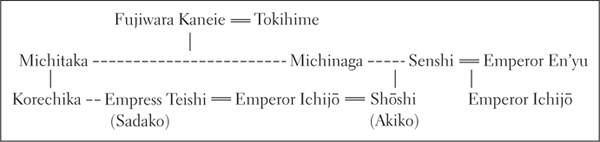

In 990 Fujiwara no Kaneie, the husband of the author of the Kagerō Diary, stepped down from his position as regent (kanpaku) and gave it to his son Fujiwara no Michitaka, who was referred to as middle regent (naka no kanpaku). Michitaka married his daughter Teishi to Emperor Ichijō (r. 986–1011) in 990, and she soon became a high consort (nyōgo) and then empress (chūgū). Sei Shōnagon became a lady-in-waiting to Teishi in 993, the year that Michitaka became prime minister (daijō daijin). In 994 Korechika, Michitaka’s eldest son and the apparent heir to the regency, became palace minister (naidaijin). In 995 Michitaka died in an epidemic, and in the following year Korechika was exiled in a move engineered by Michitaka’s younger brother and rival Michinaga, and Teishi was forced to leave the imperial palace. Sei Shōnagon continued to serve Teishi until Teishi’s death in childbirth in 1000. In the meantime, in 999, Shōshi, Michinaga’s daughter and Murasaki Shikibu’s mistress, became the chief consort to Emperor Ichijō, marking Michinaga’s ascent to the pinnacle of power.

Political context for Sei Shōnagon

THE PILLOW BOOK (MAKURA NO SŌSHI, CA. 1000)

The Pillow Book, which was finished after the demise of Teishi’s salon, focuses mainly on the years 993 and 994, when the Michitaka family and Teishi were at the height of their glory, leaving unmentioned the subsequent tragedy. Almost all the major works by women of this time were written by women in Empress Shōshi’s salon: Murasaki Shikibu, Izumi Shikibu, and Akazome’emon. Only Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book represents the rival salon of Empress Teishi. Like many other diaries by court women, The Pillow Book can be seen as a memorial to the author’s patron, specifically, an homage to the Naka no Kanpaku family and a literary prayer to the spirit of the deceased empress Teishi. One of the few indirect references to the sad circumstances that befell Teishi’s family is “The Cat Who Lived in the Palace,” about the cruel punishment, sudden exile, and ignominious return of the dog Okinamaro, who, like Korechika, secretly returned to the capital and later was pardoned.

The three hundred discrete sections of The Pillow Book can be divided into three different types—lists, essay, and diary—that sometimes overlap. The list sections consist of noun sections (mono wa), which describe particular categories of things like “Flowering Trees,” “Birds,” and “Insects” and tend to focus on nature or poetic topics, and adjectival sections (monozukushi), which describe a particular state, such as “Depressing Things,” and contain interesting lists and often are (particularly in the case of negative adjectives) humorous and witty. The diary sections, such as “The Sliding Screen in the Back of the Hall,” describe specific events and figures in history, particularly those related to Empress Teishi and her immediate family.

The essay sections sometimes focus on a specific season or month, but unlike the diary sections, they bear no historical dates. The textual variants of The Pillow Book treat these three section types differently. The Maeda and Sakai variants separate them into three large groups. By contrast, the Nōin variant and the Sankan variant, which is translated here and has become the canonical version, mix the different types of sections. The end result is that The Pillow Book appears ahistorical; events are not presented in chronological order but instead move back and forth in time, with no particular development or climax, creating a sense of a world suspended in time, a mode perhaps suitable for a paean to Teishi’s family.

Another category, which overlaps with the others and resembles anecdotal literature, is the “stories heard” (kikigaki)—that is, stories heard from one’s master or mistress—which provided knowledge and models of cultivation. Indeed, much of The Pillow Book is about aristocratic women’s education, especially the need for aesthetic awareness as well as erudition, allusiveness, and extreme refinement in communication. Sei Shōnagon shows a particular concern for delicacy and harmony, for the proper combination of object, sense, and circumstance, usually a fusion of human and natural worlds. Incongruity and disharmony, by contrast, become the butt of humor and of Sei Shōnagon’s sharp wit. The Pillow Book is often read as a personal record of accomplishments, with a number of the sections about incidents that display the author’s talent. Indeed, much of the interest of The Pillow Book has been in the strong character and personality of Sei Shōnagon.

The Pillow Book is noted for its distinctive prose style: its rhythmic, quick-moving, compressed, and varied sentences, often set up in alternating couplets. Although the typical Japanese sentence ends with the predicate, the phrases and sentences in The Pillow Book often end with nouns or eliminate the exclamatory and connective particles so characteristic of Heian women’s literature. The compact, forceful, bright, witty style stands in contrast to the soft, meandering style found in The Tale of Genji and other works by Heian women. Indeed, the adjectival sections in particular have a haikai-esque (comic linked verse) quality, marked by witty, unexpected juxtaposition.

The Pillow Book is now considered one of the twin pillars of Heian vernacular court literature, but unlike the Kokinshū, The Tales of Ise, and The Tale of Genji, which had been canonized by the thirteen century, The Pillow Book was not a required text for waka poets (perhaps because it contained relatively little poetry) and was relatively neglected in the Heian and medieval periods. But The Pillow Book became popular with the new commoner audience in the Tokugawa (Edo) period and was widely read for its style, humor, and interesting lists. By the modern period, The Pillow Book was treated as an exemplar of the zuihitsu (meanderings of the brush) or miscellany genre, centered on personal observations and musings. Since then, it has been regarded in modern literary histories as the generic predecessor of An Account of a Ten-Foot-Square Hut (Hōjōki) and Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa).

In spring it is the dawn that is most beautiful. As the light creeps over the hills, their outlines are dyed a faint red, and wisps of purplish cloud trail over them.

In summer the nights. Not only when the moon shines but on dark nights, too, as the fireflies flit to and fro, and even when it rains, how beautiful it is!

In autumn the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is a file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. When the sun has set, one’s heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.

In winter the early mornings. It is beautiful indeed when snow has fallen during the night, but splendid too when the ground is white with frost; or even when there is no snow or frost, but it is simply very cold and the attendants hurry from room to room stirring up the fires and bringing charcoal, how well this fits the season’s mood! But as noon approaches and the cold wears off, no one bothers to keep the braziers alight, and soon nothing remains but piles of white ashes.

The Cat Who Lived in the Palace (8)

The cat who lived in the palace had been awarded the headdress of nobility125 and was called Lady Myōbu. She was a very pretty cat, and His Majesty saw to it that she was treated with the greatest care.

One day she wandered onto the veranda, and Lady Uma, the nurse in charge of her, called out, “Oh, you naughty thing! Please come inside at once.” But the cat paid no attention and went on basking sleepily in the sun. Intending to give her a scare, the nurse called for the dog, Okinamaro.

“Okinamaro, where are you?” she cried. “Come here and bite Lady Myōbu!” The foolish Okinamaro, believing that the nurse was in earnest, rushed at the cat, who, startled and terrified, ran behind the blind in the imperial dining room, where the emperor happened to be sitting. Greatly surprised, His Majesty picked up the cat and held her in his arms. He summoned his gentlemen-in-waiting. When Tadataka, the chamberlain,126 appeared, His Majesty ordered that Okinamaro be chastised and banished to Dog Island. All the attendants started to chase the dog amid great confusion. His Majesty also reproached Lady Uma. “We shall have to find a new nurse for our cat,” he told her. “I no longer feel I can count on you to look after her.” Lady Uma bowed; thereafter she no longer appeared in the emperor’s presence.

The imperial guards quickly succeeded in catching Okinamaro and drove him out of the palace grounds. Poor dog! He used to swagger about so happily. Recently, on the third day of the Third Month,127 when the controller first secretary paraded him through the palace grounds, Okinamaro was adorned with garlands of willow leaves, peach blossoms on his head, and cherry blossoms around his body. How could the dog have imagined that this would be his fate? We all felt sorry for him. “When Her Majesty was having her meals,” recalled one of the ladies-in-waiting, “Okinamaro always used to be in attendance and sit across from us. How I miss him!”

It was about noon, a few days after Okinamaro’s banishment, that we heard a dog howling fearfully. How could any dog possibly cry so long? All the other dogs rushed out in excitement to see what was happening. Meanwhile, a woman who served as a cleaner in the palace latrines ran up to us. “It’s terrible,” she said. “Two of the chamberlains are flogging a dog. They’ll surely kill him. He’s being punished for having come back after he was banished. It’s Tadataka and Sanefusa who are beating him.” Obviously the victim was Okinamaro. I was absolutely wretched and sent a servant to ask the men to stop, but just then the howling finally ceased. “He’s dead,” one of the servants informed me. “They’ve thrown his body outside the gate.”

That evening, while we were sitting in the palace bemoaning Okinamaro’s fate, a wretched-looking dog walked in; he was trembling all over, and his body was fearfully swollen.

“Oh dear,” said one of the ladies-in-waiting. “Can this be Okinamaro? We haven’t seen any other dog like him recently, have we?”

We called to him by name, but the dog did not respond. Some of us insisted that it was Okinamaro; others that it was not. “Please send for Lady Ukon,” said the empress, hearing our discussion. “She will certainly be able to tell.” We immediately went to Ukon’s room and told her she was wanted on an urgent matter.

“Is this Okinamaro?” the empress asked her, pointing to the dog.

“Well,” said Ukon, “it certainly looks like him, but I cannot believe that this loathsome creature is really our Okinamaro. When I called Okinamaro, he always used to come to me, wagging his tail. But this dog does not react at all. No, it cannot be the same one. And besides, wasn’t Okinamaro beaten to death and his body thrown away? How could any dog be alive after being flogged by two strong men?” Hearing this, Her Majesty was very unhappy.

When it got dark, we gave the dog something to eat, but he refused it, and we finally decided that this could not be Okinamaro.

On the following morning I went to attend the empress while her hair was being dressed and she was performing her ablutions. I was holding up the mirror for her when the dog we had seen on the previous evening slunk into the room and crouched next to one of the pillars. “Poor Okinamaro!” I said. “He had such a dreadful beating yesterday. How sad to think he is dead! I wonder what body he has been born into this time. Oh, how he must have suffered!”

At that moment the dog lying by the pillar started to shake and tremble and shed a flood of tears. It was astounding. So this really was Okinamaro! On the previous night it was to avoid betraying himself that he had refused to answer to his name. We were immensely moved and pleased. “Well, well, Okinamaro!” I said, putting down the mirror. The dog stretched himself flat on the floor and yelped loudly, so that the empress beamed with delight. All the ladies gathered round, and Her Majesty summoned Lady Ukon. When the empress explained what had happened, everyone talked and laughed with great excitement.

The news reached His Majesty, and he too came to the empress’s room. “It’s amazing,” he said with a smile. “To think that even a dog has such deep feelings!” When the emperor’s ladies-in-waiting heard the story, they too came along in a great crowd. “Okinamaro!” we called, and this time the dog rose and limped about the room with his swollen face. “He must have a meal prepared for him,” I said. “Yes,” said the empress, laughing happily, “now that Okinamaro has finally told us who he is.”

The chamberlain, Tadataka, was informed, and he hurried along from the Table Room.128 “Is it really true?” he asked. “Please let me see for myself.” I sent a maid to him with the following reply: “Alas, I am afraid that this is not the same dog after all.” “Well,” answered Tadataka, “whatever you say, I shall sooner or later have occasion to see the animal. You won’t be able to hide him from me indefinitely.”

Before long, Okinamaro was granted an imperial pardon and returned to his former happy state. Yet even now, when I remember how he whimpered and trembled in response to our sympathy, it strikes me as a strange and moving scene; when people talk to me about it, I start crying myself.

The Sliding Screen in the Back of the Hall (11)

The sliding screen in the back of the hall in the northeast corner of Seiryō Palace is decorated with paintings of the stormy sea and of the terrifying creatures with long arms and long legs that live there.129 When the doors of the empress’s room were open, we could always see this screen. One day we were sitting in the room, laughing at the paintings and remarking how unpleasant they were. By the balustrade of the veranda stood a large celadon vase, full of magnificent cherry branches; some of them were as much as five feet long, and their blossoms overflowed to the very foot of the railing. Toward noon the major counselor, Fujiwara no Korechika,130 arrived. He was dressed in a cherry-color court cloak, sufficiently worn to have lost its stiffness, a white underrobe, and loose trousers of dark purple; from beneath the cloak shone the pattern of another robe of dark red damask. Since His Majesty was present, Korechika knelt on the narrow wooden platform in front of the door and reported to him on official matters.

A group of ladies-in-waiting was seated behind the bamboo blinds. Their cherry-color Chinese jackets hung loosely over their shoulders with the collars pulled back; they wore robes of wisteria, golden yellow, and other colors, many of which showed beneath the blind covering the half shutter. Presently the noise of the attendants’ feet told us that dinner was about to be served in the Daytime Chamber, and we heard cries of “Make way. Make way.”

The bright, serene day delighted me. When the chamberlains had brought all the dishes into the chamber, they came to announce that dinner was ready, and His Majesty left by the middle door. After accompanying the emperor, Korechika returned to his previous place on the veranda beside the cherry blossoms. The empress pushed aside her curtain of state and came forward as far as the threshold. We were overwhelmed by the whole delightful scene. It was then that Korechika slowly intoned the words of the old poem,

The days and the months flow by,

but Mount Mimoro lasts forever.131

Deeply impressed, I wished that all this might indeed continue for a thousand years.

As soon as the ladies serving in the Daytime Chamber had called for the gentlemen-in-waiting to remove the trays, His Majesty returned to the empress’s room. Then he told me to rub some ink on the inkstone. Dazzled, I felt that I should never be able to take my eyes off his radiant countenance. Next he folded a piece of white paper. “I should like each of you,” he said, “to copy down on this paper the first ancient poem that comes into your head.”

“How am I going to manage this?” I asked Korechika, who was still out on the veranda.

“Write your poem quickly,” he said, “and show it to His Majesty. We men must not interfere in this.” Ordering an attendant to take the emperor’s inkstone to each of the women in the room, he told us to make haste. “Write down any poem you happen to remember,” he said. “The Naniwazu132 or whatever else you can think of.”

For some reason I was overcome with timidity; I blushed and had no idea what to do. Some of the other women managed to put down poems about the spring, the blossoms, and such suitable subjects; then they handed me the paper and said, “Now it’s your turn.” Picking up the brush, I wrote the poem that goes,

The years have passed

and age has come my way.

Yet I need only look at this fair flower

for all my cares to melt away.

I altered the third line, however, to read, “Yet I need only look upon my lord.”133

When he had finished reading, the emperor said, “I asked you to write these poems because I wanted to find out how quick you really were.

“A few years ago,” he continued, “Emperor En’yū ordered all his courtiers to write poems in a notebook. Some excused themselves on the grounds that their handwriting was poor; but the emperor insisted, saying that he did not care in the slightest about their handwriting or even whether their poems were suitable for the season. So they all had to swallow their embarrassment and produce something for the occasion. Among them was His Excellency, our present chancellor, who was then middle captain of the third rank. He wrote down the old poem,

Like the sea that beats

upon the shores of Izumo

as the tide sweeps in,

deeper it grows and deeper—

the love I bear for you.

“But he changed the last line to read, ‘The love I bear my lord!,’ and the emperor was full of praise.”

When I heard His Majesty tell this story, I was so overcome that I felt myself perspiring. It occurred to me that no younger woman would have been able to use my poem, and I felt very lucky. This sort of test can be a terrible ordeal: it often happens that people who usually write fluently are so overawed that they actually make mistakes in their characters.

Next the empress placed a notebook of Kokinshū poems in front of her and started reading out the first three lines of each one, asking us to supply the remainder. Among them were several famous poems that we had in our minds day and night; yet for some strange reason we were often unable to fill in the missing lines. Lady Saishō, for example, could manage only ten, which hardly qualified her as knowing her Kokinshū. Some of the other women, even less successful, could remember only about half a dozen poems. They would have done better to tell the empress quite simply that they had forgotten the lines; instead they came out with great lamentations like “Oh dear, how could we have done so badly in answering the questions that Your Majesty was pleased to put to us?”—all of which I found rather absurd.

When no one could complete a particular poem, the empress continued reading to the end. This produced further wails from the women: “Oh, we all knew that one! How could we be so stupid?”

“Those of you,” said the empress, “who had taken the trouble to copy out the Kokinshū several times would have been able to complete every single poem I have read. In the reign of Emperor Murakami there was a woman at court known as the Imperial Lady of Sen’yō Palace. She was the daughter of the minister of the left who lived in the Smaller Palace of the First Ward, and of course you all have heard of her. When she was still a young girl, her father gave her this advice: ‘First you must study penmanship. Next you must learn to play the seven-string zither better than anyone else. And also you must memorize all the poems in the twenty volumes of the Kokinshū.’

“Emperor Murakami,” continued Her Majesty, “had heard this story and remembered it years later when the girl had grown up and become an imperial consort. Once, on a day of abstinence,134 he came into her room, hiding a notebook of Kokinshū poems in the folds of his robe. He surprised her by seating himself behind a curtain of state; then, opening the book, he asked, ‘Tell me the verse written by such-and-such a poet, in such-and-such a year and on such-and-such an occasion.’ The lady understood what was afoot and that it was all in fun, yet the possibility of making a mistake or forgetting one of the poems must have worried her greatly. Before beginning the test, the emperor had summoned a couple of ladies-in-waiting who were particularly adept in poetry and told them to mark each incorrect reply by a go stone. What a splendid scene it must have been! You know, I really envy anyone who attended that emperor even as a lady-in-waiting.

“Well,” Her Majesty went on, “he then began questioning her. She answered without any hesitation, just giving a few words or phrases to show that she knew each poem. And never once did she make a mistake. After a time the emperor began to resent the lady’s flawless memory and decided to stop as soon as he detected any error or vagueness in her replies. Yet, after he had gone through ten books of the Kokinshū, he had still not caught her out. At this stage he declared that it would be useless to continue. Marking where he had left off, he went to bed. What a triumph for the lady!

“He slept for some time. On waking, he decided that he must have a final verdict and that if he waited until the following day to examine her on the other ten volumes, she might use the time to refresh her memory. So he would have to settle the matter that very night. Ordering his attendants to bring up the bedroom lamp, he resumed his questions. By the time he had finished all twenty volumes, the night was well advanced; and still the lady had not made a mistake.

“During all this time His Excellency, the lady’s father, was in a state of great agitation. As soon as he was informed that the emperor was testing his daughter, he sent his attendants to various temples to arrange for special recitations of the scriptures. Then he turned in the direction of the imperial palace and spent a long time in prayer. Such enthusiasm for poetry is really rather moving.”

The emperor, who had been listening to the whole story, was much impressed. “How can he possibly have read so many poems?” he remarked when Her Majesty had finished. “I doubt whether I could get through three or four volumes. But of course things have changed. In the old days even people of humble station had a taste for the arts and were interested in elegant pastimes. Such a story would hardly be possible nowadays, would it?”

The ladies in attendance on Her Majesty and the emperor’s own ladies-in-waiting who had been admitted into Her Majesty’s presence began chatting eagerly, and as I listened I felt that my cares had really “melted away.”

A dog howling in the daytime. A wickerwork fishnet in spring.135 A red plum-blossom dress136 in the Third or Fourth Month. A lying-in room when the baby has died. A cold, empty brazier. An ox driver who hates his oxen. A scholar whose wife has one girl child after another.137

One has gone to a friend’s house to avoid an unlucky direction,138 but nothing is done to entertain one; if this should happen at the time of a seasonal change, it is still more depressing.

A letter arrives from the provinces, but no gift accompanies it. It would be bad enough if such a letter reached one in the provinces from someone in the capital; but then at least it would have interesting news about goings-on in society, and that would be a consolation.

One has written a letter, taking pains to make it as attractive as possible, and now one impatiently awaits the reply. “Surely the messenger should be back by now,” one thinks. Just then he returns; but in his hand he carries not a reply but one’s own letter, still twisted or knotted139 as it was sent, but now so dirty and crumpled that even the ink mark on the outside has disappeared. “Not at home,” announces the messenger, or else, “They said they were observing a day of abstinence and would not accept it.” Oh, how depressing!

Again, one has sent one’s carriage to fetch someone who had said he would definitely pay one a visit on that day. Finally it returns with a great clatter, and the servants hurry out with cries of “Here they come!” But next one hears the carriage being pulled into the coach house, and the unfastened shafts clatter to the ground. “What does this mean?” one asks. “The person was not at home,” replies the driver, “and will not be coming.” So saying, he leads the ox back to its stall, leaving the carriage in the coach house.

With much bustle and excitement a young man has moved into the house of a certain family as the daughter’s husband. One day he fails to come home, and it turns out that some high-ranking court lady has taken him as her lover. How depressing! “Will he eventually tire of the woman and come back to us?” his wife’s family wonder ruefully.

The nurse who is looking after a baby leaves the house, saying that she will be back soon. Soon the child starts crying for her. One tries to comfort it with games and other diversions and even sends a message to the nurse telling her to return immediately. Then comes her reply: “I am afraid that I cannot be back this evening.” This is not only depressing; it is no less than hateful. Yet how much more distressed must be the young man who has sent a messenger to fetch a lady friend and who awaits her arrival in vain!

It is quite late at night and a woman has been expecting a visitor. Hearing finally a stealthy tapping, she sends her maid to open the gate and lies waiting excitedly. But the name announced by the maid is that of someone with whom she has absolutely no connection. Of all the depressing things, this is by far the worst.

With a look of complete self-confidence on his face an exorcist prepares to expel an evil spirit from his patient. Handing his mace, rosary, and other paraphernalia to the medium who is assisting him, he begins to recite his spells in the special shrill tone that he forces from his throat on such occasions. For all the exorcist’s efforts, the spirit gives no sign of leaving, and the Guardian Demon fails to take possession of the medium.140 The relations and friends of the patient, who are gathered in the room praying, find this rather unfortunate. After he has recited his incantations for the length of an entire watch,141 the exorcist is worn out. “The Guardian Demon is completely inactive,” he tells his medium. “You may leave.” Then, as he takes back his rosary, he adds, “Well, well, it hasn’t worked!” He passes his hand over his forehead, then yawns deeply (he of all people!), and leans back against a pillar for a nap.

Most depressing is the household of some hopeful candidate who fails to receive a post during the period of official appointments. Hearing that the gentleman was bound to be successful, several people have gathered in his house for the occasion; among them are a number of retainers who served him in the past but who since then have either been engaged elsewhere or moved to some remote province. Now they all are eager to accompany their former master on his visit to the shrines and temples, and their carriages pass to and fro in the courtyard. Indoors there is a great commotion as the hangers-on help themselves to food and drink. Yet the dawn of the last day of the appointments arrives, and still no one has knocked at the gate. The people in the house are nervous and prick up their ears.

Presently they hear the shouts of forerunners and realize that the high dignitaries are leaving the palace. Some of the servants were sent to the palace on the previous evening to hear the news and have been waiting all night, trembling with cold; now they come trudging back listlessly. The attendants who have remained faithfully in the gentleman’s service year after year cannot bring themselves to ask what has happened. His former retainers, however, are not so diffident. “Tell us,” they say, “what appointment did His Excellency receive?” “Indeed,” murmur the servants, “His Excellency was governor of such-and-such a province.” Everyone was counting on his receiving a new appointment and is desolated by this failure. On the following day the people who had crowded into the house begin to slink away in twos and threes. The old attendants, however, cannot leave so easily. They walk restlessly about the house, counting on their fingers the provincial appointments that will become available in the following year. Pathetic and depressing in the extreme!

One has sent a friend a verse that turned out fairly well. How depressing when there is no reply poem! Even in the case of love poems, people should at least answer that they were moved at receiving the message or something of the sort; otherwise they will cause the keenest disappointment.

Someone who lives in a bustling, fashionable household receives a message from an elderly person who is behind the times and has very little to do; the poem, of course, is old-fashioned and dull. How depressing!

One needs a particularly beautiful fan for some special occasion and instructs an artist, in whose talents one has full confidence, to decorate one with an appropriate painting. When the day comes and the fan is delivered, one is shocked to see how badly it has been painted. Oh, the dreariness of it!

A messenger arrives with a present at a house where a child has been born or where someone is about to leave on a journey. How depressing for him if he gets no reward! People should always reward a messenger, though he may bring only herbal balls or hare sticks.142 If he expects nothing, he will be particularly pleased to be rewarded. On the other hand, what a terrible letdown if he arrives with a self-important look on his face, his heart pounding in anticipation of a generous reward, only to have his hopes dashed!

A man has moved in as a son-in-law; yet even now, after some five years of marriage, the lying-in room has remained as quiet as on the day of his arrival.

An elderly couple who have several grown-up children, and who may even have some grandchildren crawling about the house, are taking a nap in the daytime. The children who see them in this state are overcome by a forlorn feeling, and for other people it is all very depressing.

To take a hot bath when one has just woken is not only depressing; it actually puts one in a bad humor.

Persistent rain on the last day of the year.

One has been observing a period of fast but neglects it for just one day—most depressing.

A white underrobe in the Eighth Month.143

A wet nurse who has run out of milk.

One is in a hurry to leave, but one’s visitor keeps chattering away. If it is someone of no importance, one can get rid of him by saying, “You must tell me all about it next time”; but should it be the sort of visitor whose presence commands one’s best behavior, the situation is hateful indeed.

One finds that a hair has got caught in the stone on which one is rubbing one’s inkstick, or again that gravel is lodged in the inkstick, making a nasty, grating sound.

Someone has suddenly fallen ill, and one summons the exorcist. Since he is not at home, one has to send messengers to look for him. After one has had a long fretful wait, the exorcist finally arrives, and with a sigh of relief one asks him to start his incantations. But perhaps he has been exorcising too many evil spirits recently; for hardly has he installed himself and begun praying when his voice becomes drowsy. Oh, how hateful!

A man who has nothing in particular to recommend him discusses all sorts of subjects at random as though he knows everything.

An elderly person warms the palms of his hands over a brazier and stretches out the wrinkles. No young man would dream of behaving in such a fashion; old people can really be quite shameless. I have seen some dreary old creatures actually resting their feet on the brazier and rubbing them against the edge while they speak. These are the kinds of people who, when visiting someone’s house, first use their fans to wipe away the dust from the mat and, when they finally sit on it, cannot stay still but are forever spreading out the front of their hunting costume144 or even tucking it up under their knees. One might suppose that such behavior was restricted to people of humble station, but I have observed it in quite well-bred people, including a senior secretary of the fifth rank in the Ministry of Ceremonial and a former governor of Suruga.

I hate the sight of men in their cups who shout, poke their fingers in their mouths, stroke their beards, and pass on the wine to their neighbors with great cries of “Have some more! Drink up!” They tremble, shake their heads, twist their faces, and gesticulate like children who are singing, “We’re off to see the governor.” I have seen really well-bred people behave like this and I find it most distasteful.

To envy others and to complain about one’s own lot; to speak badly about people; to be inquisitive about the most trivial matters and to resent and abuse people for not telling one, or, if one does manage to worm out some facts, to inform everyone in the most detailed fashion as if one had known all from the beginning—oh, how hateful!

One is just about to be told some interesting piece of news when a baby starts crying.

A flight of crows circle about with loud caws.

An admirer has come on a clandestine visit, but a dog catches sight of him and starts barking. One feels like killing the beast.

One has been foolish enough to invite a man to spend the night in an unsuitable place—and then he starts snoring.

A gentleman has visited one secretly. Although he is wearing a tall, lacquered hat,145 he nevertheless wants no one to see him. He is so flurried, in fact, that upon leaving he bangs into something with his hat. Most hateful! It is annoying too when he lifts up the Iyo blind146 that hangs at the entrance of the room, then lets it fall with a great rattle. If it is a head blind, things are still worse, for, being more solid, it makes a terrible noise when it is dropped. There is no excuse for such carelessness. Even a head blind does not make any noise if one lifts it up gently on entering and leaving the room; the same applies to sliding doors. If one’s movements are rough, even a paper door will bend and resonate when opened; but if one lifts the door a little while pushing it, there need be no sound.

One has gone to bed and is about to doze off when a mosquito appears, announcing himself in a reedy voice. One can actually feel the wind made by his wings, and slight though it is, one finds it hateful in the extreme.

A carriage passes with a nasty, creaking noise. Annoying to think that the passengers may not even be aware of this! If I am traveling in someone’s carriage and I hear it creaking, I dislike not only the noise but also the owner of the carriage.

One is in the middle of a story when someone butts in and tries to show that he is the only clever person in the room. Such a person is hateful, and so, indeed, is anyone, child or adult, who tries to push himself forward.

One is telling a story about old times when someone breaks in with a little detail that he happens to know, implying that one’s own version is inaccurate—disgusting behavior!

Very hateful is a mouse that scurries all over the place.

Some children have called at one’s house. One makes a great fuss of them and gives them toys to play with. The children become accustomed to this treatment and start to come regularly, forcing their way into one’s inner rooms and scattering one’s furnishings and possessions. Hateful!

A certain gentleman whom one does not want to see visits one at home or in the palace, and one pretends to be asleep. But a maid comes to tell one and shakes one awake, with a look on her face that says, “What a sleepyhead!” Very hateful.

A newcomer pushes ahead of the other members in a group; with a knowing look, this person starts laying down the law and forcing advice on everyone—most hateful.

A man with whom one is having an affair keeps singing the praises of some woman he used to know. Even if it is a thing of the past, this can be very annoying. How much more so if he is still seeing the woman! (Yet sometimes I find that it is not as unpleasant as all that.)

A person who recites a spell himself after sneezing.147 In fact I detest anyone who sneezes, except the master of the house.

Fleas, too, are very hateful. When they dance about under someone’s clothes, they really seem to be lifting them up.

The sound of dogs when they bark for a long time in chorus is ominous and hateful.

I cannot stand people who leave without closing the panel behind them.

How I detest the husbands of nursemaids! It is not so bad if the child in the maid’s charge is a girl, because then the man will keep his distance. But, if it is a boy, he will behave as though he were the father. Never letting the boy out of his sight, he insists on managing everything. He regards the other attendants in the house as less than human, and if anyone tries to scold the child, he slanders him to the master. Despite this disgraceful behavior, no one dare accuse the husband; so he strides about the house with a proud, self-important look, giving all the orders.

I hate people whose letters show that they lack respect for worldly civilities, whether by discourtesy in the phrasing or extreme politeness to someone who does not deserve it. This sort of thing is, of course, most odious if the letter is for oneself, but it is bad enough even if it is addressed to someone else.

As a matter of fact, most people are too casual, not only in their letters, but in their direct conversation. Sometimes I am quite disgusted at noting how little decorum people observe when talking to each other. It is particularly unpleasant to hear some foolish man or woman omit the proper marks of respect when addressing a person of quality; and when servants fail to use honorific forms of speech in referring to their masters, it is very bad indeed. No less odious, however, are those masters who, in addressing their servants, use such phrases as “When you were good enough to do such-and-such” or “As you so kindly remarked.” No doubt there are some masters who, in describing their own actions to a servant, say, “I presumed to do so-and-so”!

Sometimes a person who is utterly devoid of charm will try to create a good impression by using very elegant language, yet he succeeds only in being ridiculous. No doubt he believes this refined language to be just what the occasion demands, but when it goes so far that everyone bursts out laughing, surely something must be wrong.

It is most improper to address high-ranking courtiers, imperial advisers, and the like simply by using their names without any titles or marks of respect; but such mistakes are fortunately rare.

If one refers to the maid who is in attendance on some lady-in-waiting as “Madam” or “that lady,” she will be surprised, delighted, and lavish in her praise.

When speaking to young noblemen and courtiers of high rank, one should always (unless their majesties are present) refer to them by their official posts. Incidentally, I have been very shocked to hear important people use the word “I” while conversing in their majesties’ presence.148 Such a breach of etiquette is really distressing, and I fail to see why people cannot avoid it.

A man who has nothing in particular to recommend him but who speaks in an affected tone and poses as being elegant.

An inkstone with such a hard, smooth surface that the stick glides over it without leaving any deposit of ink.

Ladies-in-waiting who want to know everything that is going on.

Sometimes one greatly dislikes a person for no particular reason—and then that person goes and does something hateful.

A gentleman who travels alone in his carriage to see a procession or some other spectacle. What sort of a man is he? Even though he may not be a person of the greatest quality, surely he should have taken along a few of the many young men who are anxious to see the sights. But no, there he sits by himself (one can see his silhouette through the blinds), with a proud look on his face, keeping all his impressions to himself.

A lover who is leaving at dawn announces that he has to find his fan and his paper.149 “I know I put them somewhere last night,” he says. Since it is pitch dark, he gropes about the room, bumping into the furniture and muttering, “Strange! Where on earth can they be?” Finally he discovers the objects. He thrusts the paper into the breast of his robe with a great rustling sound; then he snaps open his fan and busily fans away with it. Only now is he ready to take his leave. What charmless behavior! “Hateful” is an understatement.

Equally disagreeable is the man who, when leaving in the middle of the night, takes care to fasten the cord of his headdress. This is quite unnecessary; he could perfectly well put it gently on his head without tying the cord. And why must he spend time adjusting his cloak or hunting costume? Does he really think someone may see him at this time of night and criticize him for not being impeccably dressed?

A good lover will behave as elegantly at dawn as at any other time. He drags himself out of bed with a look of dismay on his face. The lady urges him on: “Come, my friend, it’s getting light. You don’t want anyone to find you here.” He gives a deep sigh, as if to say that the night has not been nearly long enough and that it is agony to leave. Once up, he does not instantly pull on his trousers. Instead he comes close to the lady and whispers whatever was left unsaid during the night. Even when he is dressed, he still lingers, vaguely pretending to be fastening his sash.

Presently he raises the lattice, and the two lovers stand together by the side door while he tells her how he dreads the coming day, which will keep them apart; then he slips away. The lady watches him go, and this moment of parting will remain among her most charming memories.

Indeed, one’s attachment to a man depends largely on the elegance of his leave-taking. When he jumps out of bed, scurries about the room, tightly fastens his trouser sash, rolls up the sleeves of his court cloak, overrobe, or hunting costume, stuffs his belongings into the breast of his robe, and then briskly secures the outer sash—one really begins to hate him.

A son-in-law who is praised by his father-in-law; a young bride who is loved by her mother-in-law.

A silver tweezer that is good at plucking out the hair.

A servant who does not speak badly about his master.

A person who is in no way eccentric or imperfect, who is superior in both mind and body, and who remains flawless all his life.

People who live together and still manage to behave with reserve toward each other. However much these people may try to hide their weaknesses, they usually fail.

To avoid getting ink stains on the notebook into which one is copying stories, poems, or the like. If it is a very fine notebook, one takes the greatest care not to make a blot; yet somehow one never seems to succeed.

When people, whether they be men or women or priests, have promised each other eternal friendship, it is rare for them to stay on good terms until the end.

A servant who is pleasant to his master.

One has given some silk to the fuller, and when he sends it back, it is so beautiful that one cries out in admiration.

While entertaining a visitor, one hears some servants chatting without any restraint in one of the back rooms. It is embarrassing to know that one’s visitor can overhear. But how to stop them?

A man whom one loves gets drunk and keeps repeating himself.

To have spoken about someone not knowing that he could overhear. This is embarrassing even if it is a servant or some other completely insignificant person.

To hear one’s servants making merry. This is equally annoying if one is on a journey and staying in cramped quarters or at home and hears the servants in a neighboring room.

Parents, convinced that their ugly child is adorable, pet him and repeat the things he has said, imitating his voice.

An ignoramus who in the presence of some learned person puts on a knowing air and converses about men of old.

A man recites his own poems (not especially good ones) and tells one about the praise they have received—most embarrassing.

Lying awake at night, one says something to one’s companion, who simply goes on sleeping.

In the presence of a skilled musician, someone plays a zither just for his own pleasure and without tuning it.

A son-in-law who has long since stopped visiting his wife runs into his father-in-law in a public place.

Things That Give a Hot Feeling (78)

The hunting costume of the head of a guards escort.

A patchwork surplice.

The captain in attendance at the imperial games.

An extremely fat person with a lot of hair.

A zither bag.

A holy teacher performing a rite of incantation at noon in the Sixth or Seventh Month. Or at the same time of the year a coppersmith working in his foundry.

Things That Have Lost Their Power (80)

A large boat that is high and dry in a creek at ebb tide.

A woman who has taken off her false locks to comb the short hair that remains.

A large tree that has been blown down in a gale and lies on its side with its roots in the air.

The retreating figure of a sumo wrestler who has been defeated in a match.150

A man of no importance reprimanding an attendant.

An old man who removes his hat, uncovering his scanty topknot.

A woman, who is angry with her husband about some trifling matter, leaves home and goes somewhere to hide. She is certain that he will rush about looking for her; but he does nothing of the kind and shows the most infuriating indifference. Since she cannot stay away forever, she swallows her pride and returns.

One has gone to a house and asked to see someone; but the wrong person appears, thinking that it is he who is wanted; this is especially awkward if one has brought a present.

One has allowed oneself to speak badly about someone without really intending to do so; a young child who has overheard it all goes and repeats what one has said in front of the person in question.

Someone sobs out a pathetic story. One is deeply moved; but it so happens that not a single tear comes to one’s eyes—most awkward. Although one makes one’s face look as if one is going to cry, it is no use: not a single tear will come. Yet there are times when, having heard something happy, one feels the tears streaming out.

The face of a child drawn on a melon.151

A baby sparrow that comes hopping up when one imitates the squeak of a mouse; or again, when one has tied it with a thread round its leg and its parents bring insects or worms and pop them in its mouth—delightful!

A baby of two or so is crawling rapidly along the ground. With his sharp eyes he catches sight of a tiny object and, picking it up with his pretty little fingers, takes it to show to a grown-up person.

A child, whose hair has been cut like a nun’s,152 is examining something; the hair falls over his eyes, but instead of brushing it away he holds his head to the side. The pretty white cords of his trouser skirt are tied round his shoulders, and this too is most adorable.

A young palace page, who is still quite small, walks by in ceremonial costume.

One picks up a pretty baby and holds him for a while in one’s arms; while one is fondling him, he clings to one’s neck and then falls asleep.

The objects used during the Display of Dolls.

One picks up a tiny lotus leaf that is floating on a pond and examines it. Not only lotus leaves, but little hollyhock flowers, and indeed all small things, are most adorable.

An extremely plump baby, who is about a year old and has lovely white skin, comes crawling toward one, dressed in a long gauze robe of violet with the sleeves tucked up.

A little boy of about eight who reads aloud from a book in his childish voice.

Pretty, white chicks who are still not fully fledged and look as if their clothes are too short for them; cheeping loudly, they follow one on their long legs or walk close to the mother hen.

Duck eggs.

An urn containing the relics of some holy person.

Wild pinks.

Finding a large number of tales that one has not read before. Or acquiring the second volume of a tale whose first volume one has enjoyed. But often it is a disappointment.

Someone has torn up a letter and thrown it away. Picking up the pieces, one finds that many of them can be fitted together.

One has had an upsetting dream and wonders what it can mean. In great anxiety one consults a dream interpreter, who informs one that it has no special significance.

A person of quality is holding forth about something in the past or about a recent event that is being widely discussed. Several people are gathered round him, but it is oneself that he keeps looking at as he talks.

A person who is very dear to one has fallen ill. One is miserably worried about him even if he lives in the capital and far more so if he is in some remote part of the country. What a pleasure to be told that he has recovered!

I am most pleased when I hear someone I love being praised or being mentioned approvingly by an important person.

A poem that someone has composed for a special occasion or written to another person in reply is widely praised and copied by people in their notebooks. Although this is something that has never yet happened to me, I can imagine how pleasing it must be.

A person with whom one is not especially intimate refers to an old poem or story that is unfamiliar. Then one hears it being mentioned by someone else and one has the pleasure of recognizing it. Still later, when one comes across it in a book, one thinks, “Ah, this is it!” and feels delighted with the person who first brought it up.

I feel very pleased when I have acquired some Michinoku paper or some white, decorated paper or even plain paper if it is nice and white.

A person in whose company one feels awkward asks one to supply the opening or closing line of a poem. If one happens to recall it, one is very pleased. Yet often on such occasions one completely forgets something that one would normally know.

I look for an object that I need at once, and I find it. Or again, there is a book that I must see immediately; I turn everything upside down, and there it is. What a joy!

When one is competing in an object match153 (it does not matter what kind), how can one help being pleased at winning?

I greatly enjoy taking in someone who is pleased with himself and who has a self-confident look, especially if he is a man. It is amusing to observe him as he alertly waits for my next repartee; but it is also interesting if he tries to put me off my guard by adopting an air of calm indifference as if there were not a thought in his head.

I realize that it is very sinful of me, but I cannot help being pleased when someone I dislike has a bad experience.

It is a great pleasure when the ornamental comb that one has ordered turns out to be pretty.

I am more pleased when something nice happens to a person I love than when it happens to myself.

Entering the empress’s room and finding that ladies-in-waiting are crowded round her in a tight group, I go next to a pillar that is some distance from where she is sitting. What a delight it is when Her Majesty summons me to her side so that all the others have to make way!

One Day, When the Snow Lay Thick on the Ground (157)

One day, when the snow lay thick on the ground and it was so cold that all the lattices had been closed, I and the other ladies were sitting with Her Majesty, chatting and poking the embers in the brazier.

“Tell me, Shōnagon,” said the empress, “how is the snow on Mount Xianglu?”154

I told the maid to raise one of the lattices and then rolled up the blind all the way. Her Majesty smiled. I was not alone in recognizing the Chinese poem she had quoted; in fact all the ladies knew the lines and had even rewritten them in Japanese. Yet no one but me had managed to think of it instantly.

“Yes indeed,” people said when they heard the story. “She was born to serve an empress like ours.”

It is getting so dark that I can scarcely go on writing, and my brush is all worn out. Yet I should like to add a few things before I end.

I wrote these notes at home when I had a good deal of time to myself and thought no one would notice what I was doing. Everything that I have seen and felt is included. Since much of it might appear malicious and even harmful to other people, I was careful to keep my book hidden. But now it has become public, which is the last thing I expected.

One day Lord Korechika, the minister of the center, brought the empress a bundle of notebooks. “What shall we do with them?” Her Majesty asked me. “The emperor has already made arrangements for copying the ‘Records of the Historian.’”155

“Let me make them into a pillow,”156 I said.

“Very well,” said Her Majesty. “You may have them.”

I now had a vast quantity of paper at my disposal, and I set about filling the notebooks with odd facts, stories from the past, and all sorts of other things, often including the most trivial material. On the whole I concentrated on things and people that I found charming and splendid; my notes also are full of poems and observations about trees and plants, birds and insects. I was sure that when people saw my book they would say, “It’s even worse than I expected. Now one can really tell what she is like.” After all, it is written entirely for my own amusement and I put things down exactly as they came to me. How could my casual jottings possibly bear comparison with the many impressive books that exist in our time? Readers have declared, however, that I can be proud of my work. This has surprised me greatly; yet I suppose it is not so strange that people should like it, for, as will be gathered from these notes of mine, I am the sort of person who approves of what others abhor and detests the things they like.

Whatever people may think of my book, I still regret that it ever came to light.

[Adapted from a translation by Ivan Morris]

Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) belonged to the northern branch of the Fujiwara lineage, the same branch that produced the regents. In fact, both sides of her family can be traced back to Fujiwara no Fuyutsugu (775–826), whose son Yoshifusa became the first regent (sesshō). Murasaki Shikibu’s family line, however, subsequently declined and by her grandfather’s generation had settled at the provincial governor, or zuryō, level. Murasaki Shikibu’s father, Fujiwara no Tametoki (d. 1029), although eventually appointed governor of Echizen and then Echigo, had an undistinguished career as a bureaucrat. He was able, however, to make a name for himself as a scholar of Chinese literature and a poet.

Murasaki Shikibu was probably born sometime between 970 and 978, and in 996 she accompanied her father to his new post as provincial governor in Echizen, on the coast of the Japan Sea. A year or two later, she returned to the capital to marry Fujiwara no Nobutaka, a mid-level aristocrat who was old enough to be her father. She had a daughter named Kenshi, probably in 999, and Nobutaka died a couple of years later, in 1001. It is generally believed that Murasaki Shikibu started writing The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) after her husband’s death, perhaps in response to the sorrow it caused her, and it was probably the reputation of the early chapters that resulted in her being summoned to the imperial court around 1005 or 1006. She became a lady-in-waiting (nyōbō) to Empress Shōshi, the chief consort of Emperor Ichijō and the eldest daughter of Fujiwara no Michinaga (966–1027), who had become regent. At least half of Murasaki Shikibu’s Diary (Murasaki Shikibu nikki) is devoted to a long-awaited event in Michinaga’s career—the birth of a son to Empress Shōshi in 1008—which would make Michinaga the grandfather of a future emperor.

Murasaki Shikibu was the sobriquet given to the author of The Tale of Genji when she was a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court and is not her actual name, which is not known. The name Shikibu probably comes from her father’s position in the Shikibu-shō (Ministry of Ceremonial), and Murasaki may refer to the lavender color of the flower of her clan (Fujiwara, or Wisteria Fields), or it may have been borrowed from the name of the heroine of The Tale of Genji.

THE TALE OF GENJI (GENJI MONOGATARI)

The title of The Tale of Genji comes from the surname of the hero (the son of the emperor reigning at the beginning of the narrative), whose life and relationships with various women are described in the first forty-one chapters. The Tale of Genji is generally divided into three parts. The first part, consisting of thirty-three chapters, follows Genji’s career from his birth through his exile and triumphant return to his rise to the pinnacle of society, focusing equally, if not more, on the fate of the various women with whom he becomes involved. The second part, chapters 34 to 41, from “New Herbs” (Wakana) to “The Wizard” (Maboroshi), explores the darkness that gathers over Genji’s private life and that of his great love Murasaki, who eventually succumbs and dies, and ends with Genji’s own death. The third part, the thirteen chapters following Genji’s death, is concerned primarily with the affairs of Kaoru, Genji’s putative son, and the three sisters (Ōigimi, Nakanokimi, and Ukifune) with whom Kaoru becomes involved. In the third part, the focus of the book shifts dramatically from the capital and court to the countryside and from a society concerned with refinement, elegance, and the various arts to an other-worldly, ascetic perspective—a shift that anticipates the movement of mid-Heian court culture toward the eremetic, religious literature of the medieval period.

The Tale of Genji both follows and works against the plot convention of the Heian monogatari in which the heroine, whose family has declined or disappeared, is discovered and loved by an illustrious noble. This association of love and inferior social status appears in the opening line of Genji and extends to the last relationship between Kaoru and Ukifune. In the opening chapter, the reigning emperor, like all Heian emperors, is expected to devote himself to his principal consort (the Kokiden lady), the lady with the highest rank, and yet he dotes on a woman of considerably lower status, a social and political violation that eventually results in the woman’s death. Like the protagonist of The Tales of Ise, Genji pursues love where it is forbidden and most unlikely to be found or attained. In “Lavender” (Wakamurasaki), chapter 5, Genji discovers the young Murasaki, who has lost her mother and is in danger of losing her only guardian until Genji takes her into his home.

In Murasaki Shikibu’s day, it would have been unheard of for a man of Genji’s high rank to take a girl of Murasaki’s low position into his own residence and marry her. In the upper levels of Heian aristocratic society, the man usually lived in his wife’s residence, in either her parents’ house or a dwelling nearby (as Genji does with Aoi, his principal wife). The prospective groom had high stakes in the marriage, for the bride’s family provided not only a residence but other forms of support as well. When Genji takes into his house a girl (like the young Murasaki) with no backing or social support, he thus is openly flouting the conventions of marriage as they were known to Murasaki Shikibu’s audience. In the monogatari tradition, however, this action becomes a sign of excessive, romantic love.

Some of the other sequences—involving Yūgao, the Akashi lady, Ōigimi, and Ukifune—start on a similar note. All these women come from upper- or middle-rank aristocratic families (much like that of the author herself) that have, for various reasons, fallen into social obscurity and must struggle to survive. The appearance of the highborn hero implies, at least for the attendants surrounding the woman, an opportunity for social redemption. Nonetheless, Murasaki Shikibu, much like her female predecessor, the author of the Kagerō Diary, concentrates on the difficulties that the woman subsequently encounters, in either dealing with the man or failing to make the social transition between her own social background and that of the highborn hero. The woman may, for example, be torn between pride and material need or between emotional dependence and a desire to be more independent, or she may feel abandoned and betrayed—all conflicts explored in The Tale of Genji. In classical Japanese poetry, such as that by Ono no Komachi, love has a similar fate: it is never about happiness or the blissful union of souls. Instead, it dwells on unfulfilled hopes, regretful partings, fears of abandonment, and lingering resentment.

The Tale of Genji is remarkable for how well it absorbs the psychological dimension of the Kagerō Diary and the social romance of the early monogatari into a deeply psychological narrative revolving around distinctive characters. Despite closely resembling the modern psychological novel, The Tale of Genji was not conceived and written as a single work and then distributed to a mass audience, as novels are today. Instead, it was issued in very short installments, chapter by chapter or sequence by sequence, to an extremely circumscribed, aristocratic audience over an extended period of time.

As a result, The Tale of Genji can be read and appreciated as Murasaki Shikibu’s oeuvre, or corpus, as a closely interrelated series of texts that can be read either individually or as a whole and that is the product of an author whose attitudes, interests, and techniques evolved significantly with time and experience. For example, the reader of the Ukifune narrative can appreciate this sequence both independently and as an integral part of the previous narrative. Genji can also be understood as a kind of multiple bildungsroman in which a character is developed through time and experience not only in the life of a single hero or heroine but also over different generations, with two or more characters. Genji, for example, attains an awareness of death, mutability, and the illusory nature of the world through repeated suffering. By contrast, Kaoru, his putative son, begins his life, or rather his narrative, with a profound grasp and acceptance of these darker aspects of life. In the second part, in the “New Herbs” chapters, Murasaki has long assumed that she can monopolize Genji’s affections and act as his principal wife. But Genji’s unexpected marriage to the Third Princess (Onna san no miya) crushes these assumptions, causing Murasaki to fall mortally ill. In the last ten chapters, the Uji sequence, Ōigimi never suffers in the way that Murasaki does, but she quickly becomes similarly aware of the inconstancy of men, love, and marriage and rejects Kaoru, even though he appears to be an ideal companion.

Murasaki Shikibu probably first wrote a short sequence of chapters, perhaps beginning with “Lavender,” and then, in response to her readers’ demand, wrote a sequel or another related series of chapters, and so forth. Certain sequences, particularly the Broom Tree sequence (chapters 2–4, 6) and its sequels (chapters 15 and 16), which appear to have been inserted later, focus on women of the middle and lower aristocracy, as opposed to the main chapters of the first part, which deal with Fujitsubo and other upper-rank women related to the throne. The Tamakazura sequence (chapters 22–31), which is a sequel to the Broom Tree sequence, may be an expansion of an earlier chapter no longer extant. The only chapters whose authorship has been questioned are the three chapters following the death of Genji. The following selections are from the third part, after Genji’s death, beginning with “The Lady at the Bridge” (chap. 45) and the story of the Eighth Prince, his daughters, and Kaoru.

Main Characters

AKASHI EMPRESS: Consort and later empress of the emperor reigning at the end of the tale. Mother of numerous princes and princesses, including Prince Niou.

BENNOKIMI: daughter of Kashiwagi’s wet nurse, and later attendant to the Eighth Prince and the Uji princesses. Confidante of Kaoru.

CAPTAIN: former son-in-law of Ono nun. Unsuccessfully courts Ukifune.

EIGHTH PRINCE: eighth son of the first emperor to appear in the tale. Genji’s half brother. Father of Ōigimi, Nakanokimi, and Ukifune. Ostracized by court society for his part in Kokiden’s plot to supplant the crown prince (the future Reizei emperor). Retreats to Uji, where he raises Ōigimi and Nakanokimi and devotes himself to Buddhism.

EMPEROR: The fourth and last emperor in the tale, ascending to the throne after the Reizei emperor. Father of Niou.

GENJI: son of the first emperor by the Kiritsubo lady and the protagonist of the first and second parts.

JIJŪ: attendant to Ukifune.

KAORU: thought by the world to be Genji’s son by the Third Princess but really Kashiwagi’s son. Befriends the Eighth Prince and falls in love with his daughter Ōigimi but fails to make her his wife. Subsequently pursues his other daughters, Nakanokimi and Ukifune. Marries the Second Princess.

KASHIWAGI: eldest son of Tō no Chūjō. Falls in love and has an illicit affair with the Third Princess. Later dies a painful death. Father of Kaoru.

KOJIJŪ: attendant to the Third Princess and helps Kashiwagi’s secret affair with the Third Princess.

MURASAKI: Genji’s great love. Daughter of Prince Hyōbu by a low-ranking wife, and niece of Fujitsubo.

NAKANOKIMI: second Uji princess, daughter of the Eighth Prince. Marries Niou and is installed by him at Nijō mansion. Bears him a son.

NIOU, PRINCE: beloved third son of the last emperor and the Akashi empress. Looked after by Murasaki until her death. Marries Nakanokimi and later Rokunokimi. Pursues Ukifune.

ŌIGIMI: eldest daughter of the Eighth Prince. Loved by Kaoru but refuses to marry him.

ONO NUN: sister of the bishop of Yokawa. Takes care of Ukifune after her disappearance from Uji and attempts to marry her to the captain, her former son-in-law.

REIZEI EMPEROR: thought to be the son of the first emperor and Fujitsubo but actually Genji’s son.

ROKUNOKIMI: sixth daughter of Yūgiri. Becomes Niou’s principal wife.

SECOND PRINCESS: Second daughter of the fourth and last emperor. Principal wife of Kaoru.

TŌ NO CHŪJŌ: son of the Minister of the Left and brother of Aoi. Genji’s chief male companion in his youth. Son-in-law of the Minister of the Right. Father of Kashiwagi.

TOKIKATA: Niou’s retainer.

UKIFUNE: unrecognized daughter of the Eighth Prince by an attendant. Half sister of Ōigimi and Nakanokimi. Raised in the East. Pursued by Kaoru and Niou. Tries to commit suicide but is saved by the bishop of Yokawa and taken to a convent at Ono, where she becomes a nun.

UKON: attendant to Ukifune.

YOKAWA, BISHOP OF: high priest of Yokawa and brother of Ono nun. Discovers Ukifune, looks after her, and gives her the tonsure.

YŪGIRI: son of Genji by Aoi. Becomes the most powerful figure at court after Genji’s death. Marries his daughter Rokunokimi to Niou.

There was in those years a prince of the blood, an old man, left behind by the times. His mother was of the finest lineage. There had once been talk of seeking a favored position for him; but there were disturbances and a new alignment of forces,157 at the end of which his prospects were in ruins. His supporters, embittered by this turn of events, were less than steadfast: they made their various excuses and left him. And so in his public life and in his private, he was quite alone, blocked at every turn. His wife, the daughter of a former minister, had fits of bleakest depression at the thought of her parents and their plans for her, now of course in ruins. Her consolation was that she and her husband were close as husbands and wives seldom are. Their confidence in each other was complete.

But here too there was a shadow: the years went by and they had no children. If only there were a pretty little child to break the loneliness and boredom, the prince would think—and sometimes give voice to his thoughts. And then, surprisingly, a very pretty daughter was in fact born to them. She was the delight of their lives. Years passed, and there were signs that the princess was again with child. The prince hoped that this time he would be favored with a son, but again the child was a daughter. Though the birth was easy enough, the princess fell desperately ill soon afterward, and was dead before many days had passed. The prince was numb with grief. The vulgar world had long had no place for him, he said, and frequently it had seemed quite unbearable; and the bond that had held him to it had been the beauty and the gentleness of his wife. How could he go on alone? And there were his daughters. How could he, alone, rear them in a manner that would not be a scandal?—for he was not, after all, a commoner. His conclusion was that he must take the tonsure. Yet he hesitated. Once he was gone, there would be no one to see to the safety of his daughters.

So the years went by. The princesses grew up, each with her own grace and beauty. It was difficult to find fault with them, they gave him what pleasure he had. The passing years offered him no opportunity to carry out his resolve.

The serving women muttered to themselves that the younger girl’s very birth had been a mistake, and were not as diligent as they might have been in caring for her. With the prince it was a different matter. His wife, scarcely in control of her senses, had been especially tormented by thoughts of this new babe. She had left behind a single request: “Think of her as a keepsake, and be good to her.”

The prince himself was not without resentment at the child, that her birth should so swiftly have severed their bond from a former life, his and his princess’s.

“But such was the bond that it was,” he said. “And she worried about the girl to the very end.”

The result was that if anything he doted upon the child to excess. One almost sensed in her fragile beauty a sinister omen.

The older girl was comely and of a gentle disposition, elegant in face and in manner, with a suggestion behind the elegance of hidden depths. In quiet grace, indeed, she was the superior of the two. And so the prince favored each as each in her special way demanded. There were numerous matters which he was not able to order as he wished, however, and his household only grew sadder and lonelier as time went by. His attendants, unable to bear the uncertainty of their prospects, took their leave one and two at a time. In the confusion surrounding the birth of the younger girl, there had not been time to select a really suitable nurse for her. No more dedicated than one would have expected in the circumstances, the nurse first chosen abandoned her ward when the girl was still an infant. Thereafter the prince himself took charge of her upbringing.

Years pass, and the prince refuses to marry again, despite the urging of the people around him. He spends much of his time in religious observances but cannot bring himself to renounce the world. His daughters are his principal companions. As they grow up, he notices that although both are quiet and reserved, the elder, Ōigimi, tends to be moody, and the younger, Nakanokimi, possesses a certain shy gaiety.

He was the Eighth Prince, a younger brother of the shining Genji. During the years when the Reizei emperor was crown prince, the mother of the reigning emperor had sought in that conspiratorial way of hers to have the Eighth Prince named crown prince, replacing Reizei. The world seemed hers to rule as she wished, and the Eighth Prince was very much at the center of it. Unfortunately his success irritated the opposing faction. The day came when Genji and presently Yūgiri had the upper hand, and he was without supporters. He had over the years become an ascetic in any case, and he now resigned himself to living the life of the sage and hermit.

There came yet another disaster. As if fate had not been unkind enough already, his mansion was destroyed by fire. Having no other suitable house in the city, he moved to Uji, some miles to the southeast, where he happened to own a tastefully appointed mountain villa. He had renounced the world, it was true, and yet leaving the capital was a painful wrench indeed. With fishing weirs near at hand to heighten the roar of the river, the situation at Uji was hardly favorable to quiet study. But what must be must be. With the flowering trees of spring and the leaves of autumn and the flow of the river to bring repose, he lost himself more than ever in solitary meditation. There was one thought even so that never left his mind: how much better it would be, even in these remote mountains, if his wife were with him!

“She who was with me, the roof above are smoke.

And why must I alone remain behind?”

So much was the past still with him that life scarcely seemed worth living.

Mountain upon mountain separated his dwelling from the larger world. Rough people of the lower classes, woodcutters and the like, sometimes came by to do chores for him.158 There were no other callers. The gloom continued day after day, as stubborn and clinging as “the morning mist on the peaks.”159

There happened to be in those Uji mountains an abbot,160 a most saintly man. Though famous for his learning, he seldom took part in public rites. He heard in the course of time that there was a prince living nearby, a man who was teaching himself the mysteries of the Good Law. Thinking this a most admirable undertaking, he made bold to visit the prince, who upon subsequent interviews was led deeper into the texts he had studied over the years. The prince became more immediately aware of what was meant by the transience and uselessness of the material world.

“In spirit,” he confessed, quite one with the holy man, “I have perhaps found my place upon the lotus of the clear pond; but I have not yet made my last farewells to the world because I cannot bring myself to leave my daughters behind.”

The abbot was an intimate of the Reizei emperor and had been his preceptor as well. One day, visiting the city, he called upon the Reizei emperor to answer any questions that might have come to him since their last meeting.

“Your honored brother,” he said, bringing the Eighth Prince into the conversation, “has pursued his studies so diligently that he has been favored with the most remarkable insights. Only a bond from a former life can account for such dedication. Indeed, the depth of his understanding makes me want to call him a saint who has not yet left the world.”

“He has not taken the tonsure? But I remember now—the young people do call him ‘the saint who is still one of us.’”

Kaoru chanced to be present at the interview. He listened intently. No one knew better than he the futility of this world, and yet he passed useless days, his devotions hardly so frequent or intense as to attract public notice. The heart of a man who, though still in this world, was in all other respects a saint—to what might it be likened?

The abbot continued: “He has long wanted to cut his last ties with the world, but a trifling matter made it difficult for him to carry out his resolve. Now he has two motherless children whom he cannot bring himself to leave behind. They are the burden he must bear.”161

The abbot himself had not entirely given up the pleasures of the world: he had a good ear for music. “And when their highnesses deign to play a duet,” he said, “they bid fair to outdo the music of the river, and put one in mind of the blessed musicians above.”

The Reizei emperor smiled at this rather fusty way of stating the matter. “You would not expect girls who have had a saint for their principal companion to have such accomplishments. How pleasant to know about them—and what an uncommonly good father he must be! I am sure that the thought of having to leave them is pure torment. It is always possible that I will live longer than he, and if I do perhaps I may ask to be given responsibility for them.”

He was himself the tenth son of the family, younger than his brother at Uji. There was the example of the Suzaku emperor, who had left his young daughter in Genji’s charge. Something similar might be arranged, he thought. He would have companions to relieve the monotony of his days.

Kaoru was less interested in the daughters than in the father. Quite entranced with what he had heard, he longed to see for himself that figure so wrapped in the serenity of religion.

“I have every intention of calling on him and asking him to be my master,” he said as the abbot left. “Might I ask you to find out, unobtrusively, of course, how he would greet the possibility?”