Chapter 3

THE KAMAKURA PERIOD

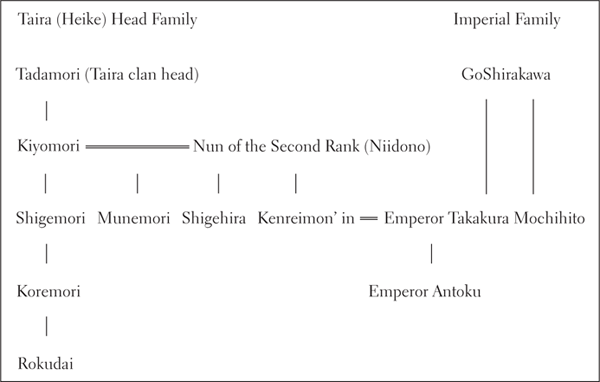

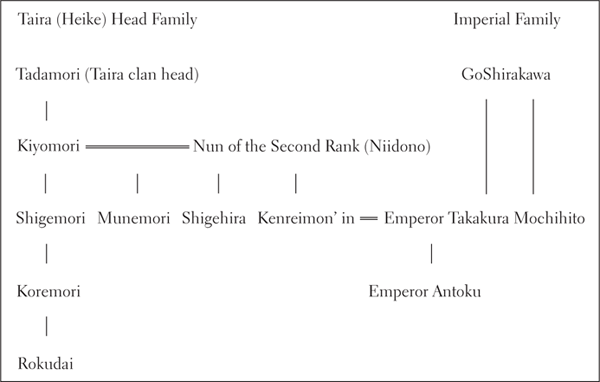

The Kamakura period began in 1183 with the establishment of the bakufu, or military government, in Kamakura, near present-day Tokyo, by Minamoto Yoritomo, the leader of the Minamoto (Genji) clan, which defeated the Heike (Taira) in 1185. The Genpei war between the Genji and the Heike is vividly recounted in the epic narrative The Tales of the Heike, part of which is translated here. After the end of the Genpei war, a struggle broke out between Yoritomo and his younger brother Yoshitsune, a prominent Minamoto military leader, who was killed in 1189 by Fujiwara no Yasuhira, a general of the Fujiwara clan in Ōshū (northeast Honshū). Yoritomo, in turn, destroyed the Fujiwara forces, thus ending all major domestic armed conflict. The legends surrounding Yoshitsune can be found in The Story of Yoshitsune (Gikeiki).

After Yoritomo’s death, control of the bakufu passed from the Minamoto to the Hōjō family, led by Hōjō Masako (1157–1225), the wife of Yoritomo and the mother of Minamoto Sanetomo (1192–1219), the third shogun and a noted waka poet. A key political turning point in the Kamakura period was the Jōkyū rebellion in 1221, when, in an attempt to regain direct imperial power from the military, the retired emperor GoToba (r. 1183–1198, 1180–1239) attacked the Hōjō but was soundly defeated and exiled to the small and remote island of Oki. The Jōkyū rebellion revealed the weakness of the nobility and the emperor and the growing strength of the samurai class, whose power had risen in the late Heian period. GoToba’s exile to Oki is nostalgically recounted in The Clear Mirror (Masukagami, 1338–1376), a vernacular historical chronicle, in a section translated in this book.

The Kamakura period ended in 1333 with the defeat of Hōjō Takatoki (1303–1333) and the Hōjō clan by Emperor GoDaigo (r. 1318–1339, 1288–1339), who gained power briefly, for two years, during the Kenmu restoration (1333–1336), before being defeated by another military clan, the Ashikaga. GoDaigo retreated to Yoshino, south of the capital, and established the Southern Court and the beginning of the rival court system known as the Northern and Southern Courts period (1336–1392). The political career of Emperor GoDaigo and his failed attempt at imperial restoration is one of the focal points of the Taiheiki (Chronicle of Great Peace, 1340s–1371), a major military chronicle whose highlights are included here.

The Kamakura period marks the beginning of the so-called medieval period, a four-hundred-year span from the fall of the Heike (Taira) clan in 1185 to the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, when Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542–1616) triumphed over his rivals and unified the country under his control. Sometimes the beginning of the medieval period is pushed back as far as the beginning of the Heian period (794–1185), and sometimes the end of the medieval period is pushed forward as far as the end of the Tokugawa (Edo) period (1600–1867). Generally, however, the Kamakura period (1183–1333), the Northern and Southern Courts (Nanbokuchō) period (1336–1392), and the Muromachi period (1392–1573), when warrior society came to the fore, are considered to be the three main historical divisions of the medieval period.

The Muromachi period extended from the rule by the Ashikaga clan, based in Kyoto (in the Muromachi quarter), through the end of the Northern and Southern Courts era to the defeat of the fifteenth shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki by Oda Nobunaga in 1573. The latter half of the Muromachi period is referred to as the Warring States (Sengoku) period, from the beginning of the Ōnin war (1467–1477) to 1573, when Oda Nobunaga destroyed the Ashikaga bakufu and unified the country. The Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1598) refers to the short period of time when two powerful generals, first Oda Nobunaga and then Toyotomi Hideyoshi, gained national power before eventually succumbing to Tokugawa Ieyasu at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. The most striking cultural and literary changes occurred between the early medieval period, from the fall of the Heike clan in 1185 to the fall of the Kamakura bakufu in 1333, and the late medieval period, from the Kenmu restoration onward, with a particularly significant break after the Ōnin war that forced the aristocratic culture, centered in the capital for many centuries, to disperse to the provinces.

THE SAMURAI AND LITERATURE

One of the principal aspects of medieval society was the emergence of a warrior government and culture. As a result of the Hōgen (1156) and Heiji (1159) rebellions, the Heike (Taira), a military clan, displaced the Fujiwara clan which had dominated the throne and the court for most of the Heian period. If the ascendance of the Heike is considered the beginning of the warrior rule then the medieval period begins with the first year of Hōgen (1156). But the Heike elite emulated the Fujiwara regents before them, continuing the court bureaucratic system based in Kyoto, and they soon were defeated by the Genji (Minamoto), who established a military government in Kamakura, between 1183 and 1185. Minamoto Yoritomo’s establishment of a bakufu in Kamakura resulted in two political centers—a court government in Kyoto and a military government in the east—thereby laying the foundation for a system of dual cultures.

During the medieval period, the bakufu in the east gradually increased its control to the point that the court government in Kyoto lost its political power. Seeing their fortunes waning, the aristocrats in Kyoto occasionally tried to restore the imperial authority of the court-centered government. But the Jōkyū rebellion in 1221 ended in failure, and the Kenmu restoration lasted for only two years. The extended struggle during the Northern and Southern Courts period, when the imperial court was split, eventually ended these attempts and dispersed the nobility, with the political power permanently shifting to the military. The result in the Muromachi period was the full emergence of a samurai-based society and culture.

As the social and economic status of the samurai rose, their cultural activities multiplied as well. During the early medieval period, the samurai were drawn to aristocratic culture and the culture of the capital, which they tried to imitate. Although there were very few samurai waka poets during the Heian period, their number steadily increased during the medieval period. The most prominent was Minamoto Sanetomo (1192–1219), the third Kamakura bakufu shogun (1203–1219), who took an interest in Man’yōshū-style poetry. In the late medieval period, scholars and poets of samurai origin such as Imagawa Ryōshun (1326–1414), Tō no Tsuneyori (1401–1484), and Hosokawa Yūsai (1534–1610) became prominent, and a number of renga masters had samurai origins.

The first major works of “warrior” literature during the medieval period are the military chronicles (gunki-mono), which were organized chronologically and focused on the lives and families of samurai. Relatively few samurai actually helped produce these chronicles, however. More often, they were the work of fallen or lesser aristocrats (often recluses) or Buddhist priests, who gave military narratives like The Tales of the Heike a heavily Buddhistic and aristocratic coloring. Likewise, in the latter half of the medieval period, the founder of kōwakamai (ballad drama), Momonoi Kōwakamaru (1393–1470), the scion of a warrior family, gave kōwakamai a samurai flavor. The other playwrights of nō drama and kōwakamai were not samurai, although samurai did form an important part of the audience.

THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND THE WAY OF THE GODS

The Genpei war and subsequent military struggles left their survivors with a deep sense of the impermanence of the world. For followers of Buddhism, the situation was so apocalyptic that it signaled for them the latter age of the Buddhist law (mappō). Buddhism promised worldly benefits (protection, rewards in this life) as well as future salvation, a sense of sustenance amid turmoil and uncertainty. Buddhism had entered Japan from China as early as the sixth century and, especially Tendai and Shingon Buddhism, had become a central institution in Heian aristocratic society, but not until the late Heian period did it begin to penetrate commoner society at large.

Innovative priests who had become disillusioned with the older, established Buddhist institutions in the capitals of Nara and Kyoto created new Buddhist schools that appealed to commoners, who often were unable to read the Buddhist scriptures. Hōnen (1133–1212) founded the Jōdo (Pure Land) sect, which had a profound influence on medieval culture, and his disciple Shinran (1173–1262) created the Shinshū (New Pure Land) sect. A generation later, Ippen (1239–1289) founded the Jishū (Time) sect. These Pure Land sects, which stressed the recitation of the name of the Amida Buddha, promised an easily attainable way to salvation, relying on the power of grace and the benevolence of the Amida Buddha. The hymns and personal writings of these Pure Land leaders, particularly those by Hōnen, are included here both because of their high literary quality and as a necessary context for understanding medieval literary texts like The Tales of the Heike, which are based on Kamakura Pure Land beliefs. Zen Buddhism, which was imported from China in the medieval period and welcomed by the samurai in Kamakura, stressed meditation, non-dualism, and a frugal, minimalist lifestyle.

As the Buddhist sects (including Tendai, which continued to exert considerable institutional influence) rose in prominence, so too did belief in the native gods (kami), which laid the foundation for the institutional rise of Shinto (Way of the Gods) and its various local and national deities. Samurai leaders such as Minamoto Yoritomo, the founder of the Kamakura bakufu, worshiped and relied on both kami and buddhas. Kami were believed to bring worldly benefits and protections for the state, the community, and the clan, and they became the focus of worship at major shrines like the Ise Shrine. One result was the emerging doctrine of Japan as a “country of the gods” (shinkoku), evident in later Northern and Southern Courts-period texts such as Kitabatake Chikafusa’s Chronicle of the Gods (Jinnō shōtōki, 1343). The rise of popular Buddhism and of cults of native gods led to a belief in honji suijaku (original ground—manifest traces), according to which Shinto gods are local manifestations (suijaku) of original buddhas (honji). This syncretist view had precedents in earlier periods but became prominent in the medieval period and is a frequent motif of the setsuwa of the Kamakura period and of the otogi-zōshi of the Muromachi period.

THE ARISTOCRACY AND LITERATURE

Even while their political and economic status declined, the aristocracy retained their prestige as the custodians of high culture and canonical literature, and the long tradition of aristocratic court literature continued to flourish in the early medieval period. Indeed, the first thirty or forty years of the Kamakura period, until the Jōkyū rebellion in 1221 when the power of the nobility was abruptly terminated, represents one of the peaks of aristocratic literature. Some of the greatest waka anthologies—beginning with the Shinkokinshū (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems, ca. 1205), the eighth imperial waka collection and often considered the finest of the twenty-one imperial waka anthologies—were compiled at this time. The best poetic treatises, such as Fujiwara Shunzei’s Poetic Styles from the Past (Korai fūteishō, 1197) and Fujiwara Teika’s Essentials of Poetic Composition (Eiga taigai, ca. 1222), were written during the early decades of the Kamakura period, an age of increased cultural production by the aristocracy. In fact, more monogatari (tales) were written during the early medieval period than in the Heian period, although many such works were imitative, drawing heavily on The Tale of Genji, which had become a model for literary and poetic composition. It was not until the Muromachi period that the monogatari received new stimulus from commoner culture, taking the form of what are now called otogi-zōshi (Muromachi tales).

Aristocratic literature in the medieval period was characterized by strong nostalgia for the Heian-court past and an emphasis on preserving court traditions. Indeed, literary production was the only means for many aristocrats to make a living on the basis of their heritage. The twenty-first and last imperial waka anthology, the Shinshokukokinshū, edited in 1439, symbolically marked the end of aristocratic literature. Not only did the aristocrats compose waka and monogatari in the medieval period, but they also turned their attention to preserving their cultural inheritance by collating, annotating, and commenting on earlier texts. Their scholarship extended from ancient texts such as the Kojiki, Nihon shoki, and Man’yōshū to major Heian texts like the Kokinshū, The Tales of Ise, and The Tale of Genji, which became the three most heavily annotated texts. The work by these aristocrats (beginning with Fujiwara Teika, who produced what became the most authoritative versions of The Tale of Genji) in constructing and transmitting the literary canon was eventually shared by other social groups, the priests and the samurai, who also had a strong nostalgia for the Heian classics. Two great literary figures of the late Muromachi period were Shōtetsu (1381–1459), a prolific and innovative poet who is regarded as one of the last distinguished exponents of classical waka, and the renga (linked verse) master Sōgi (1421–1502), of commoner birth, who wrote influential treatises on renga and numerous commentaries on the Heian classics. Such commentaries were motivated by the fact that Japanese poetry, specifically waka and renga, the two most important literary forms, required a knowledge of the diction and allusive associations of the Heian classics.

THE PRIESTHOOD AND LITERATURE

The contribution of the Buddhist priesthood to literature was enormous, especially in light of the dominant role that Buddhism played throughout the period. The first major contribution was the hōgo, teachings of the Buddhist law in kana prose. Although Buddhist writings such as the Record of Miraculous Events in Japan (Nihon ryōiki) and The Essentials of Salvation (Ōjōyōshū) appeared in the mid-Heian period, they were written in Chinese. In the Kamakura period, however, the priest-intellectuals of the new Buddhist sects wrote in kana, thereby producing vernacular Buddhist literature. Buddhist leaders like Shinran and Ippen also wrote wasan (Buddhist hymns), which made their teachings easily accessible and available for wide dissemination. Equally important was Zen Buddhism, introduced to Japan by Dōgen (1200–1253) and others. One product of Zen culture was the literature of the Five Mountains (Gozan bungaku), writings in Chinese by Zen priests from the late thirteenth to the sixteenth century, with which Ikkyū (1394–1481), whose poetry is included here, was associated. Zen Buddhism also had a profound impact on nō drama, as is evident in works such as Stupa Komachi (Sotoba Komachi).

Equally important were the collections of setsuwa edited by Buddhist priests and used for preaching to commoners. Setsuwa were collected from as early as the Nara period, beginning with the Nihon ryōiki, and appeared in the late Heian period in the massive Collection of Tales of Times Now Past (Konjaku monogatari shū), but it was in the Kamakura period that most of the setsuwa collections were edited and produced. At that time a new type of setsuwa emerged: the engi-mono (tales of origins), which describe the origins and miraculous benefits of the god or buddha worshiped by a specific temple or shrine complex. Engi-mono were produced by the priests or shrine officials at the religious site, using historical documents and popular legend to record, embellish, or reinvent the history of the temple or shrine and to advertise the powers of the enshrined deity. Almost all of them were preserved as illustrated scrolls (emakimono). A good example is “The Avatars of Kumano” in the Shintōshū, about the origin of the gods of the Kumano Shrine. Similar kinds of illustrated scrolls formed the basis for the later Muromachi otogi-zōshi. A sekkyō (sermon-ballad) tradition emerged in which priests narrated or chanted Buddhist teachings or engi-mono with a musical accompaniment. In the late medieval period this tradition was consolidated as sekkyō-bushi (ballads sung to the beat of the sasara), performed by commoner storytellers. This genre became the basis of sekkyō jōruri (ballads sung to shamisen accompaniment), a medium for narrating double suicides and revenge tales that eventually evolved into jōruri (puppet theater) in the Tokugawa period. Buddhist priest-storytellers (monogatari sō) also became specialists in narrating military chronicles like the Taiheiki (Chronicle of Great Peace).

Buddhist priests were also prominent composers of waka and renga. In fact, there is probably no genre in the medieval period that was not related to the Buddhist clergy. One consequence is that Buddhist thought permeates medieval literature: warrior tales, historical chronicles, setsuwa, essays (zuihitsu), nō drama, otogi-zōshi, and sekkyō-bushi. Even the treatises on waka, renga, and nō drama are permeated by Buddhist perspectives. In sum, all forms of cultural production in the medieval period were inseparable from Buddhist concepts and worldviews. This is why the notion that literature amounts to nothing more than kyōgen kigo (wild words and decorative phrases) came to the fore. On the one hand, in the Buddhist context, literature and its production were thought to be illusory and even an impediment to salvation, encouraging worldly attachments. On the other hand, it could, as argued in the selections from the Collection of Sand and Pebbles (Shasekishū, 1279–1283), be rationalized by Buddhist writers as an expedient means (hōben) of teaching the Buddhist law and leading readers (or listeners) to insight and, ultimately, enlightenment.

SAIGYŌ

Satō Norikiyo, now known as Saigyō (1118–1190), was the son of a wealthy family of hereditary warrior aristocrats. At the age of fifteen, he entered the service of the powerful Tokudaiji family, and later he served the retired emperor Toba as one of the Northern Guard (Hokumen no bushi), a select group of military bodyguards. Members of the Northern Guard also served as cultural companions to the retired emperor, exhibiting skill in poetry, music, kemari,1 and other aristocratic pastimes. For reasons still being debated, in 1140, at the age of twenty-three, Saigyō suddenly abandoned his post and his family to become a Buddhist monk. For the next fifty years, Saigyō alternately lived in seclusion, traveled about the country, spent time in the capital, and carried out various Buddhist activities. Throughout his tonsured life, Saigyō continued to compose poetry, increasing his fame. The pinnacle of Saigyō’s poetic influence came fifteen years after his death, when ninety-four of his poems (more than those of any other poet) were included in the imperially sponsored Shinkokinshū (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems, ca. 1205).

Although reliable historical documents concerning Saigyō’s life are scarce, the autobiographical nature of many of his poems has fed the imagination of readers for centuries, giving rise to a vast body of semilegendary material. “The Woman of Pleasure at Eguchi,” from the Tales of Renunciation (Senjūshō), is a good example of how Saigyō’s poems became the object of legends. It now is nearly impossible to separate the legend Saigyō from the actual poet and his poems. Saigyō spent many years in and around the capital and nearly thirty years in relative seclusion near Mount Kōya, the headquarters of the Shingon Buddhist establishment. He is best known as a travel poet, making the long and arduous trip to Michinoku (northeastern Honshū) twice—once shortly after becoming a monk and again when he was around sixty-nine years of age. He also traveled to Shikoku, Kumano, and Ise, where he spent the duration of the Genpei (Heike/Genji) war (1180–1186). After the fighting ended, Saigyō returned to the capital and then to Kawachi (near present-day Osaka), where he lived out his remaining years, dying on the sixteenth day of the Second Month in 1190.

Although Saigyō composed poetry covering the entire range of traditional waka topics, his most famous poems are on travel, reclusion, cherry blossoms, and the moon. Travel was an established category in both waka composition and the imperially sponsored anthologies. Later interpreters and scholars have perceived a special sense of immediateness in Saigyō’s travel poetry. Many waka poets never saw the poetic sites they described in their poems, relying instead on established associations of poetic place-names. Even though Saigyō is known for his travels, he also composed many poems on famous places without visiting them.

Similarly, it is not entirely clear just how secluded from the world Saigyō was. He likely lived alone in the capital or far away in Kōya or Ise, but he probably was never in total seclusion. Rather, he lived near and associated with others who had abandoned the world. Furthermore, Saigyō nourished ties with the poetic establishment; he maintained relationships with high-ranking aristocrats and imperial personages from the time of his service as a samurai; and he actively participated in poetic and Buddhistic activities in and around the capital as well as at Kōya and Ise.

SELECTED POEMS

Saigyō is noted for his poetry on cherry blossoms, being especially fond of the blossoms in the mountainous region of Yoshino, not far from Mount Kōya. Saigyō’s cherry blossom poems often express a sense of attachment to the blossoms and have been interpreted as self-remonstrative in the Buddhist sense. Saigyō’s moon poems also carry Buddhist overtones, for in both Buddhist sutras and waka, the moon is the symbol of enlightenment. Many of Saigyō’s moon poems also, however, retain the traditional association of love or longing.

Saigyō’s poetry is marked by unadorned self-expression, seeming simplicity of diction, self-reflection, and the interweaving of nature imagery with Buddhist motifs and ideals. These traits have made his poems among the most popular and influential in the poetic canon.

SANKASHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 723

At the time that I decided to abandon the world, some people at Higashiyama composed on the topic “expressing one’s feelings on mist.”

| sora ni naru | The empty sky |

| kokoro wa haru no | of my heart |

| kasumi ni te | enshrouded in spring mist |

| yo ni araji to mo | rises to thoughts of |

| omoi tatsu kana | leaving the world behind.2 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, LOVE, NO. 1267; SANKASHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 727

When I was staying somewhere far away, I sent the following to someone in the capital around the time of the moon.

| tsuki nomi ya | Only the moon |

| uwa no sora naru | in the sky above |

| katami ni te | a vacant reminder, |

| omoi mo ideba | should you think of me, |

| kokoro kayowamu | perhaps it will link your heart to mine.3 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1535

| sutsu to naraba | If I’ve forsaken |

| ukiyo o itou | the world of sorrows |

| shirushi aramu | there must be proof I despise it— |

| ware ni wa kumore | shroud yourself for me, |

| aki no yo no tsuki | autumn night moon.4 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1611; SANKASHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 728

When I abandoned the world and was on my way to Ise, I composed this at Suzuka-yama (Bell Deer Mountain).

| Suzuka-yama | Suzuka Mountain, |

| ukiyo o yoso ni | I’ve tossed aside the world of sorrows |

| furisutete | as a stranger to myself, |

| ika ni nariyuku | so what note will I now sound, |

| waga mi naruran | what will become of me?5 |

SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 66

| Yoshino yama | Since the day |

| kozue no hana o | I saw the treetop blossoms |

| mishi hi yori | in Yoshino’s mountains |

| kokoro wa mi ni mo | my heart has not stayed |

| sowazu nari ni ki | with my body at all.6 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 617

| Yoshino yama | Mount Yoshino, |

| yagate ideji to | I’d like to stay |

| omou mi o | and never leave, |

| hana chirinaba to | though some are surely waiting, thinking |

| hito ya matsuran | “once the blossoms have fallen …”7 |

SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 76

| hana ni somu | Why should my heart |

| kokoro no ikade | remain stained |

| nokorikemu | by blossoms, |

| sutehateteki to | when I thought |

| omou waga mi ni | I had tossed all that away?8 |

SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 87

When I thought I’d like some peace and quiet, people came to see the cherry blossoms.

| hanami ni to | Wanting to see the blossoms |

| muretsutsu hito no | people come in droves |

| kuru nomi zo | to visit—this alone |

| atara sakura no | regrettably |

| toga ni wa arikeru | is the cherry tree’s fault.9 |

SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 139

On the topic “cherry blossoms scattering in a dream,” composed with others at the residence of the former Kamo Priestess.

| harukaze no | When I dream |

| hana o chirasu to | of spring wind |

| miru yume wa | scattering cherry blossoms |

| samete mo mune no | my heart stirs |

| sawagu narikeri | even after waking.10 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1471

| yo no naka o | When I think of |

| omoeba nabete | this world |

| chiru hana no | all is scattering blossoms, |

| waga mi o satemo | so where else |

| izuchi kamo semu | might I choose to be?11 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1846; SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 77

| negawaku wa | My wish is |

| hana no shita nite | to die in spring |

| haru shinan | under the cherry blossoms |

| sono kisaragi no | on that day in the Second Month |

| mochizuki no koro | when the moon is full.12 |

SANKASHŪ, SPRING, NO. 78

| hotoke ni wa | Offer up |

| sakura no hana o | cherry blossoms |

| tatematsure | to the deceased, |

| waga nochi no yo o | if anyone wishes to mourn me |

| hito toburawaba | after I’m gone.13 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, AUTUMN 1, NO. 362; SANKASHŪ, AUTUMN, NO. 470

Composed along the way to somewhere in autumn.

| kokoro naki | Even one |

| mi ni mo aware wa | with no heart could not help |

| shirarekeri | but know pathos: |

| shigi tatsu sawa no | a snipe takes flight in a marsh |

| aki no yūgure | this autumn evening.14 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, WINTER, NO. 625

| Tsu no kuni no | Was spring at Naniwa |

| Naniwa no haru wa | in Tsu Province |

| yume nare ya | a dream? |

| ashi no kareha ni | Wind blows |

| kaze wataru nari | over the withered reeds’ leaves.15 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1676

| furuhata no | From a tree |

| soba no tatsu ki ni | standing on a cliff |

| iru hato no | by an old field |

| tomo yobu koe no | the voice of a dove calling a friend |

| sugoki yūgure | in the eerie twilight.16 |

SANKASHŪ, AUTUMN, NO. 414

With a certain purpose in mind, I went to Ichinomiya in Aki. Along the way, at a place called Takatomi Bay, I was stopped for a while by the wind. Upon seeing moonlight filtering through a rush-thatched hut, I composed the following:

| nami no oto o | My heart troubled |

| kokoro ni kakete | by the sound of the waves, |

| akasu kana | I spend the night, |

| toma moru tsuki no | my only friend the moon’s light |

| kage o tomo ni te | winnowing through this hut.17 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, AUTUMN 1, NO. 472

| kirigirisu | Cricket, |

| yosamu ni aki no | as the autumn night cold |

| naru mama ni | wears on, |

| yowaru ka koe no | are you weakening? |

| tōzakariyuku | Your voice grows more distant.18 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, WINTER, NO. 627

| sabishisa ni | I wish there were another here |

| taetaru hito no | who could bear |

| mata mo are na | this loneliness; |

| iori narabemu | we’d build our huts side by side |

| fuyu no yamazato | in this wintry mountain village.19 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, SUMMER, NO. 262

| michinobe ni | In the shade |

| shimizu nagaruru | of a roadside willow |

| yanagi kage | near a clear flowing stream |

| shibashi tote koso | I stopped, |

| tachidomaritsure | for just a while, I thought.20 |

KIKIGAKISHŪ, NO. 165

When I was living in Saga, I and others wrote poems in a light vein.

| unaiko ga | The sound of children |

| susami ni narasu | playfully blowing |

| mugibue no | straw whistles |

| koe ni odoroku | wakes me from my |

| natsu no hirubushi | summer afternoon nap.21 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, TRAVEL, NO. 987

Composed when going to the eastern provinces.

| toshi takete | Did I ever imagine |

| mata koyubeshi to | I would make this pass again |

| omoiki ya | in my old age? |

| inochi narikeri | Such is life! |

| Sayanonaka yama | Sayanonaka Mountain.22 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1613

On Mount Fuji, composed when carrying out religious practices in the eastern provinces.

| kaze ni nabiku | Trailing in the wind, |

| Fuji no keburi no | Fuji’s smoke |

| sora ni kiete | fades into the sky |

| yukue mo shiranu | destination unknown, |

| waga omoi kana | just like my own thoughts!23 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, MISCELLANEOUS, NO. 1536

| fuke ni keru | As I ponder |

| waga yo no kage o | my waning shadow |

| omou ma ni | of life far gone, |

| haruka ni tsuki no | in the distance |

| katabuki ni keri | the moon sets.24 |

SHINKOKINSHŪ, BUDDHIST POEMS, NO. 1978

On looking at one’s heart.

| yami harete | Darkness dispels, |

| kokoro no sora ni | and the moon shining clear |

| sumu tsuki wa | in my heart’s sky |

| nishi no yamabe ya | now seems to near |

| chikaku naruramu | the western hills.25 |

[Introduction and translations by Jack Stoneman]

FUJIWARA NO TEIKA

Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241), or Sadaie, was the son of Shunzei and heir to the Mikohidari house of poetry. Teika was recognized at a fairly early age as one of the most controversially innovative poets of his generation, and he was one of the four primary compilers of the Shinkokinshū. From the age of eighteen to the age of seventy-four, he kept a diary entitled the Meigetsuki. Between 1185 and 1199, he began to explore a new poetic style, which was criticized as “daruma” poems, or “incomprehensible” poems. Despite his audacious experiments with syntax and disdain for convention, Teika could also be remarkably conservative, especially in his later years, and notoriously called for a return to early classical models of composition. His dictum “new meanings, old words” is an emblem of the difficult demands he made for originality within the constraints of precedent. Few poets were able to follow Teika’s demands without resorting to tedious conventionalism. This fact, combined with his overwhelming influence as the patriarch of the dominant schools of court poetry for several centuries, is often blamed for the stultification of courtly waka after the thirteenth century. Forty-six of Teika’s poems were included in the Shinkokinshū.

ESSENTIALS OF POETIC COMPOSITION (EIGA NO TAIGAI, CA. 1222)

Essentials of Poetic Composition explains Teika’s approach to waka composition in his later years and reflects a fundamental technique of medieval aristocratic literature: allusive variation. Essentials of Poetic Composition divides poetic technique into three key notions: meaning (kokoro), diction (kotoba), and style (fūtei). The meaning (kokoro) of a poem should be neither “old” (inishie) nor “modern” (ima); instead, it should be “new” (atarashi). Teika usually uses the word kokoro in close relation to the “topic” (dai). Thus a more elaborate translation of the opening line would be: “For the meaning of the poem as it relates to the essence of the given topic, one should, above all, be innovative.” Diction (kotoba), by contrast, should be “old.” What kokoro and kotoba have in common here is that neither can be “modern.”

Teika also contrasts “modern poets”—from the latter half of the twelfth century—with “ancient poets” and strictly forbids drawing on either the diction or the meaning introduced by “modern poets”—that is, those writing in the past seventy or eighty years. For him, diction must be circumscribed and publicly recognized. “Old diction” is not a matter of age but of the canon. “Old words” refers to the poetic diction exemplified in the Three Collections (Sandaishū): the Kokinshū, Gosenshū, and Shūishū, the first three imperial collections of waka. The only exceptions are the poems of the Man’yōshū, primarily those by Hitomaro, Akahito, and Yakamochi, which are included in the Thirty-six Poets’ Collection (Sanjūrokuninshū), compiled by Fujiwara no Kintō in the mid-Heian period. With regard to “style” (fūtei), however, Teika notes that one should learn from poets both “old and new.” In summary, the meaning of the poem should be new; its diction should derive from the superior poems in the Three Collections: and the superior poems of both old and new poets should provide a model for poetic style.

Teika also is concerned about plagiarism and the lack of originality. His rules for allusive variation (honkadori) on a base poem are an extension of those he prescribed for kotoba and represent a solution to the difficulties imposed by the necessity of using only “old” diction. At the end of the preface, which is written in kanbun, Teika notes that “one should always keep in mind the scene [keiki] of old poetry and let it sink deep into the heart.” Keiki refers to not just the poetic scenes and images that appear in the poetic world but also its poetic associations. Significantly, Chinese poetry, which played a significant role in the development of Heian waka, became a major source for these associations. In the original text, certain lines appear to be notes—as they are in smaller print than that of the main text—and have been placed in parentheses in the translation.

As for the meaning [kokoro] of poetry, newness must come first. (One must seek a conception or an approach that has yet to be used.) When it comes to diction [kotoba], one must use old words. (One must not use anything not found in the Three Collections. The poems of ancient poets collected in the Shinkokinshū can be used in the same way.) The style [fūtei] of poetry can be learned from the superior poems of superior poets of the past. (One should not be concerned about the period but just learn from appropriate poems.)

Regarding the conception and diction of recent poets, even if it is a new phrase, one should be careful and leave it alone. (In regard to the poetry of those poets, one should never use the words from poems composed in the last seventy or eighty years.)

Poets frequently use and compose with the words of the poetry of the ancients. That already is a trend. But when using old poems and composing new poems, taking three out of the five measures [ku]26 is too much, and these poems will lack freshness. It is permissible to take three or four syllables more than two measures [ku]. However, it is too much if the content is the same and one uses words from old poems. (For example, using a foundation poem on flowers to compose on flowers or using a foundation poem on the moon to compose on the moon.) One should take a foundation poem on the seasons and compose on love or miscellaneous topics, or take a foundation poem on love and miscellaneous topics and compose on the four seasons. If done in this way, there probably will be no problems with borrowing from old poetry….

One should always keep in mind the scene [keiki] of old poetry and let it sink deep into the heart. One should learn in particular from the Kokinshū, The Tales of Ise, Gosenshū, Shūishū, and from superior poets in the Thirty-six Poets’ Collection. (Those who should come to mind from the Thirty-six Poets’ Collection are Hitomaro, Ki no Tsurayuki, Tadamine, Ise, Ono no Komachi, and so on.)

Even if one is not a master of Japanese poetry, in order to understand the seasonal scenes, the ups and downs of the human world, and the essence of things, one should always be sure to absorb the first twenty volumes of Bo Juyi’s Collected Works.27 (These deeply resonate with Japanese poetry.)

Poetry has no master. One simply makes the old poems one’s teacher. If one dyes one’s heart in the old style and learns from the words of one’s predecessors, who would not be able to learn to compose poetry? No one.

SHINKOKINSHŪ (NEW COLLECTION OF ANCIENT AND MODERN POEMS, CA. 1205)

The Shinkokinwakashū, better known as the Shinkokinshū, is an anthology of nearly two thousand Japanese poems (waka), all in the same standard prosodic form, thirty-one syllables in five measures. It was compiled and edited during the first two decades of the thirteenth century and was the eighth in what became a series of twenty-one anthologies of classical poetry created in response to an imperial edict, beginning with the Kokinshū (ca. 905) and ending with the Shinshokukokinshū (1439). Its title—literally, New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems or New Kokinshū—implies that the Shinkokinshū was conceived and edited in calculated emulation of the first such imperially commissioned collection. The attempt to produce an anthology that would match, if not surpass, the achievements of the Kokinshū was widely deemed successful in the judgment of later generations. Its chronological scope is broader, not only because it postdates the Kokinshū by three centuries, but also because it includes poetry by authors of earlier periods deliberately excluded from the Kokinshū, and the range of styles encompassed is arguably richer. The question of which of these collections is superior, makes for better reading, or serves as a more reliable model for aspiring poets has been the subject of debate for several centuries and has not yet been resolved.

Following the precedent of the Kokinshū, the Shinkokinshū has two prefaces, one in Sino-Japanese kanbun and one in kana. The poems are arranged by topics into twenty volumes. The topics or poetic themes of these books generally follow the conventions established by the Kokinshū but, in their details, are much closer to the precedent of the Senzaishū (1187), the seventh imperially commissioned anthology. In chronological order from one through twenty, the topics consist of two books on spring; one on summer; two on autumn; one on winter; one each on felicitations, mourning, parting, and travel; five on love; three of miscellany; and one each on poems on Shinto and Buddhist topics. Quantitatively, the emphasis is on seasonal poems and poems of love, the favored genres for public, formal poetic composition. But the Shinkokinshū allows for considerably more coverage, compared with the Kokinshū, of “miscellaneous” topics, which tend to consist of personal reflections on the contingencies of life. The typology of the Shinkokinshū’s twenty books was sufficient to encompass the entire range of topics considered suitable, as of the late twelfth century, for the composition of court poetry and thus gives a rough overview of how the world of poetic experience was partitioned at the time. Given the immense authority accorded to the Kokinshū in the construction of this world, even the less conspicuous departures from its precedent are significant. That is, the Kokinshū contains virtually no poetry on specifically Buddhist topics, and its few more or less explicitly Shinto-inspired poems are mainly in the two books of miscellany. Anagrammatic (mono no na) poems, which make up the entire tenth book of the Kokinshū, have disappeared. All the poems in variant prosody (zōtai) have been omitted as well.

In each of the twenty books, but most noticeably in the books of seasonal and love poems and those on miscellaneous topics, the compilers took great care to arrange their materials into clusters of poems on the same conventional topics, such as “Beginning of Autumn” (risshū, the first seventeen poems in the first book of autumn), with common images or motifs (in this instance, “Autumn Winds”). These clusters were often linked by word associations (engo) to adjacent clusters. The effect of this was a sense of progression, with intermittent digressions, through the phases of seasonal change or movement toward the inevitable disappointments of a courtly love affair. The subtleties of such patterns were complicated and sometimes undermined by efforts to alternate sequences of recent poems—the “modern” of the anthology’s title—with those by “ancient” poets, and by deleting individual poems during the ultimately unfinished process of revising the anthology over many years.

Especially significant for appreciating the changes in the topography of decorum that the editors of the Shinkokinshū sought is the resulting exclusion of haikai (dissonant poems), which were included among poems of variant prosody (zōtai) in the Kokinshū.28 The question raised by the exclusion of haikai from the Shinkokinshū is one of many about the designs of this collection’s editors and, by extension, about the meaning of its title. Was the “renewal” of courtly poetic traditions suggested by its title meant to be a return to the origins, a restoration of the hallowed traditions of early court poetry, or an affirmation of new directions in poetic practice? Numerous and diverse answers have been proposed, but it is up to the reader to decide.

The poems translated here were selected from works by poets of the late twelfth century most prominently represented in the anthology, those who defined its distinctive aesthetic. As far as possible, the translations are literal in the sense that each word of the English answers to some word or wording of the Japanese. The poems are parsimonious in form and extravagant in sense, and if the English is ambiguous or occasionally obscure, it is (ideally) because the text is so to more or less the same degree. The poems achieve their depths and breadth through the exploitation of a received array of figures and an accepted vocabulary of connotations, as well as through techniques of punning (kakekotoba) and allusions to earlier classical poems (honka-dori) and subtexts (honsetsu), all of which made it possible for a single phrase or word to resonate well beyond its denotative sense. The commentary attempts to explicate some of what the poets presumably expected their readers to take for granted or recognize anew, supplies the honka (base poem) or honsetsu (subtext) in translation, and provides occasional citations from early commentaries or from the judgments of the poetry matches in which many of the poems originally were presented.

Spring 1

1

On the motif “Spring Begins.”

| Miyoshino wa | Fair Yoshino, mountains |

| yama mo kasumite | now wrapped in mist: |

| shirayuki no | to the village where snow |

| furinishi sato ni | was falling |

| haru wa kinikeri | spring has come.29 |

The Regent Prime Minister30

3

When the poet presented a hundred-verse set of poems, a poem on “Spring.”

| yamafukami | By a gate of pine |

| haru to mo shiranu | in mountains too deep |

| matsu no to ni | to know spring has come, |

| taedae kakaru | one by one they fall, |

| yuki no tamamizu | jewel drops of melting snow.31 |

Princess Shokushi32

4

For a fifty-verse set of poems composed for presentation to the retired emperor.

| kakikurashi | Cloud-darkened, |

| nao furusato no | this ancient village: |

| yuki no uchi ni | in falling snow |

| ato koso miene | not a trace of spring, |

| haru wa kinikeri | yet surely it has come.33 |

Kunaikyō34

23

On the topic “Lingering Cold,” for a hundred-verse poetry match at the poet’s residence.

| sora wa nao | Under skies still |

| kasumi mo yarazu | awaiting mist, |

| kaze saete | the wind chills |

| yukige ni kumoru | a spring night’s moon |

| haru no yo no tsuki | hiding in snow-fraught clouds.35 |

The Regent Prime Minister

24

At the Bureau of Poetry, on the motif “Spring Mountain Moon.”

| yama fukami | In mountains deep |

| nao kage samushi | a spring moon’s light |

| haru no tsuki | still cold— |

| sora kakikumori | the sky thickens with clouds |

| yuki wa furitsutsu | as snow falls and falls.36 |

Echizen

25

On the topic “Spring Vista at a Waterside Village,” when Japanese poems were matched with poems in Chinese.

| Mishima-e ya | By the Bay of Mishima |

| shimo mo mada hinu | even as frost lingers |

| ashi no ha ni | spring winds |

| tsunogumu hodo no | call forth new shoots |

| harukaze zo fuku | from withered reeds.37 |

Michiteru

26

On the topic “Spring Vista at a Waterside Village,” when Japanese poems were matched with poems in Chinese.

| yūzukuyo | Evening of a new moon— |

| shio michikuru rashi | the tide must be rising |

| Naniwa-e no | in the Bay of Naniwa: |

| ashi no wakaba ni | over the young shoots of reeds |

| koyuru shiranami | crests of white waves.38 |

Hidetō

36

When some courtiers were making verses in Chinese and matching poems to them, a poem on “Water.”

| miwataseba | Gazing out over |

| yamamoto kasumu | mist-shrouded foothills |

| Minasegawa | beyond the river Minase, |

| yūbe wa aki to | who could have thought |

| nani omoiken | evenings are autumn?39 |

The Retired Emperor GoToba

37

For a poetry match at the residence of the regent prime minister, on the motif “Spring Dawn.”

| kasumi tatsu | Mist rises over |

| Sue no Matsuyama | Far Pine Mountain— |

| honobono to | faintly aglow, |

| nami ni hanaruru | a sky of drifting clouds |

| yokogumo no sora | parts from the waves.40 |

Fujiwara no Ietaka41

38

For a fifty-verse set of poems composed at the request of the cloistered Prince Shukaku.

| haru no yo no | A spring night’s |

| yume no ukihashi | floating bridge of dreams |

| todaeshite | breaks: |

| mine ni wakaruru | sky of cloud drift |

| yokogumo no sora | parting from a mountain peak.42 |

Fujiwara no Teika43

44

When the poet presented a hundred-verse set of poems.

| ume no hana | On sleeves scented |

| nioi o utsusu | by blossoms of plum |

| sode no ue ni | moonlight spilling |

| noki-moru tsuki no | through the eaves |

| kage zo arasou | claims its place. |

Fujiwara no Teika

45

When the poet presented a hundred-verse set of poems.

| ume ga ka ni | When I ask of the past |

| mukashi o toeba | in the scent of the plum, |

| haru no tsuki | the spring moon |

| kotaenu kage zo | keeps still |

| sode ni utsureru | glistening on my sleeves.44 |

Fujiwara no Ietaka

47

For the Poetry Match in Fifteen Hundred Rounds.

| ume no hana | Never do I tire of their |

| akanu iro kamo | color or their scent: |

| mukashi ni te | plum blossoms |

| onaji katami no |

the spring night’s moon |

| haru no yo no tsuki | recalling the past.45 |

Master of the Household of the Dowager Empress, Shunzei

58

For the hundred-verse poetry match at the regent prime minister’s residence.

| ima wa tote | The wild geese in the field, |

| tanomu no kari mo | knowing it’s time to leave, |

| uchiwabinu | cry plaintively: |

| oborozukiyo no | mist-shrouded moon |

| akebono no sora | lingering in the dawn sky.46 |

Priest Jakuren

Spring 2

133

For a picture of Mount Yoshino on a sliding screen panel at Saishōshitennō-in.

| Miyoshino no | Flowers must be falling |

| takane no sakura | on Yoshino’s peaks: |

| chirinikeri | this spring dawn’s |

| arashimo shiroki | gusting winds |

| haru no akebono | blossom in white.47 |

The Retired Emperor GoToba

134

For the Poetry Match in Fifteen Hundred Rounds.

| sakurairo no | Of winds of spring in my garden |

| niwa no harukaze | of the color of cherry blossoms |

| ato mo nashi | not a trace, nor visitor |

| towaba zo hito no | to take these petals |

| yuki to dani min | for fallen snow.48 |

Fujiwara no Teika

Summer

179

Composed as a poem on “Beginning of Summer.”

| orifushi mo | As seasons change |

| utsureba kaetsu | they too change |

| yo no naka no | their flowered robes: |

| hito no kokoro no | the fickle hearts of |

| hanazome no koromo | men of this world.49 |

Daughter of Shunzei50

Autumn 1

361

Topic unknown.

| sabishisa wa | Loneliness has no |

| sono iro to shi mo | color of its own: |

| nakarikeri | pine trees |

| maki tatsu yama no | on a darkening mountain |

| aki no yūgure | evening of autumn.51 |

Priest Jakuren

363

For a hundred-verse set of poems composed at the suggestion of Priest Saigyō.

| miwataseba | Looking out across |

| hana mo momiji mo | the shore |

| nakarikeri | no flowers, no autumn leaves: |

| ura no tomaya no | a thatched hut’s |

| aki no yūgure | evening of autumn.52 |

Fujiwara no Teika

380

When the poet presented a hundred-verse set of poems, a poem on “The Moon.”

| nagame-wabinu | Gazing till weary of these skies |

| aki yori hoka no | I long for a dwelling |

| yado mogana | away from autumn: |

| no ni mo yama ni mo | must the moon light |

| tsuki ya sumuran | every field and mountain?53 |

Princess Shokushi

419

When the poet had a fifty-verse set of poems on “The Moon” composed for delivery at his residence.

| tsuki dani mo | Heedless that the moon |

| nagusamegataki | brings sadness enough |

| aki no yo no | to this autumn night, |

| kokoro mo shiranu | the wind |

| matsu no kaze kana | sighs in the pines.54 |

The Regent Prime Minister

420

When the regent prime minister had a fifty-verse set of poems on “The Moon” composed for delivery at his residence.

| samushiro ya | On a mat of rush |

| matsu yo no aki no | as autumn winds deepen |

| kaze fukete | her night of waiting, |

| tsuki o katashiku | the Maiden of Uji Bridge |

| Uji no Hashihime | spreads a robe of moonlight.55 |

Fujiwara no Teika

Winter

671

When the poet presented a hundred-verse set of poems.

| koma tomete | No shelter to rest my horse |

| uchiharau | or brush my sleeves, |

| kage mo nashi | not a shadow |

| Sano no watari no | at Sano Crossing |

| yuki no yūgure | in snow-falling dusk.56 |

Fujiwara no Teika

Mourning

788

In the autumn of the year his mother died, on a day of windstorms, the poet went to the place where he had once lived with his mother.

| tamayura no | Not fleeting drops |

| tsuyu mo namida mo | of dew nor tears will pause: |

| todomarazu | winds of autumn |

| nakihito kouru | sweep the dwelling |

| yado no akikaze | loved by one now gone. |

Fujiwara no Teika

Travel

939

For a fifty-verse set of poems composed for presentation [to the retired emperor].

| akeba mata | Yet another mountain peak |

| koyubeki yama no | to be crossed after dawn? |

| mine nareya | White clouds touched |

| sorayuku tsuki no | by the distant reach |

| sue no shirakumo | of the setting moon. |

Fujiwara no Ietaka

Love 1

1034

For a hundred-verse set of poems, on the topic “Love Endured.”

| tama no o yo | If this jewel thread of life |

| taenaba taene | is to break, let it break: |

| nagaraeba | living on |

| shinoburu koto no | would be to endure |

| yowari mo zo suru | love’s torment alone.57 |

Princess Shokushi

1035

For a hundred-verse set of poems, on the topic “Love Endured.”

| wasurete wa | Another evening’s sighs: |

| uchinagekaruru | have I forgotten |

| yūbe kana | this hidden longing |

| ware nomi shirite | is mine alone to suffer |

| suguru tsukibi o | as days become months?58 |

Princess Shokushi

Love 2

1136

Among the poems for the Minase-koi Poetry Match on fifteen topics, on the motif “Spring Love.”

| omokage no | My loved one’s image |

| kasumeru tsuki zo | shimmers in the misted moon |

| yadorikeru | of a spring now past |

| haru ya mukashi no | dwelling in tears |

| sode no namida ni | on my sleeves.59 |

Daughter of Shunzei

Love 3

1206

Composed as a poem of love.

| kaeru sa no | Does he now gaze |

| mono to ya hito no | as one returning might |

| nagamuran | on the moon at dawn |

| matsu yo-nagara no | of this night |

| ariake no tsuki | I waited in vain?60 |

Fujiwara no Teika

Miscellaneous Topics 3

1764 (1762)

At the Bureau of Poetry, on the motif “Regretting.”

| oshimu to mo | I do not regret these |

| namida ni tsuki mo | heartfelt tears |

| kokoro kara | nor the earnest moon |

| narenuru sode ni | shining on my sleeves |

| aki o uramite | resenting autumn.61 |

The same poem might be translated as

| oshimu to mo | I do not grudge autumn |

| namida ni tsuki mo | nor my sleeves drenched |

| kokoro kara | in heartfelt tears, |

| narenuru sode ni | too familiar moonlight |

| aki o uramite | resenting both. |

Daughter of Shunzei

[Introduction and translations by Lewis Cook]

RECLUSE LITERATURE (SŌAN BUNGAKU)

During the late Heian and early Kamakura periods, many aristocrats took holy vows and retreated from the secular world, not to the busy Buddhist monasteries in Nara and the capital (such as Mount Hiei, the headquarters of the Tendai sect), but to retreats outside the cities, which they believed to be a purer form of renunciation. The physical separation from the secular world freed the “recluses” from heavy obligations to their families or superiors and allowed for devotion to their own interests, which often included literary and cultural pursuits. Many of these recluse monks were intellectuals and artists who produced what is now referred to as “recluse literature” (sōan bungaku). Recluse literature, which contains some of the finest writing in this period, is characterized by a deep interest in nature and in self-reflection. Prominent figures are Saigyō in the late Heian period; Kamo no Chōmei, author of An Account of a Ten-Foot-Square Hut (Hōjōki) in the early Kamakura period; and Kenkō, who wrote Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa) in the fourteenth century. Prominent recluse figures in the late medieval period include Sōgi (1421–1502), a renga master and literary scholar; and Yamazaki Sōkan (1465–1533), one of the founders of haikai (comic or popular linked verse).

KAMO NO CHŌMEI

Kamo no Chōmei (1155?–1216) was born into a family of hereditary Shinto priests who had served many generations at the Shimogamo (Kamo) Shrine, a prestigious shrine just north of the capital. Chōmei was the second son of Kamo no Nagatsugu, the head administrator of the shrine. As a child, Chōmei lived in comfortable circumstances and studied classical poetry (waka) and music, but his father died young while Chōmei was still in his teens, leaving him without the means for social advancement. Chōmei, however, continued to devote himself to the study of poetry and music, two fields in which he excelled.

In 1200, Chōmei began composing with the prominent poets of the day and was invited in 1201 by the retired emperor GoToba to take a prestigious position in the Imperial Poetry Office, where the imperial waka anthologies were edited and compiled. In the spring of 1204, at around the age of fifty, Chōmei suddenly took holy vows. It is generally believed that the cause for his sudden retirement was his disillusionment in not having received a high position at the Tadasu Shrine, part of the Shimogamo Shrine complex, a position for which he had long hoped but which was blocked by the shrine’s existing head administrator.

AN ACCOUNT OF A TEN-FOOT-SQUARE HUT (HŌJŌKI, 1212)

Chōmei wrote An Account of a Ten-Foot-Square Hut at the end of the Third Month of 1212 while in retirement at Hino, in the hills southeast of Kyoto. It is written in a mixed Japanese–Chinese style that draws heavily on Chinese and Buddhist words and sources. Probably the most noticeable rhetorical feature of this style is the heavy use of parallel phrases and of metaphors. The work is noted for its vivid descriptions of a series of disasters in the capital during a time of turmoil (the war between the Taira and Minamoto at the end of the twelfth century) and for its description of the law of impermanence of all things, one of the central tenets of Buddhism, which had a profound impact on Japan at this time. As a recluse who retreats from society and turns toward the pursuit of the Pure Land, a western paradise envisioned by the Pure Land Buddhist sect, the author is representative of a larger movement among the cultural elite at this time. In the end, however, Chōmei finds himself in the paradoxical position of advocating detachment and rebirth in the Pure Land while at the same time becoming attached to the beauties of nature and the four seasons and the aesthetic life of his ten-foot-square hut at Hino.

The current of the flowing river does not cease, and yet the water is not the same water as before. The foam that floats on stagnant pools, now vanishing, now forming, never stays the same for long. So, too, it is with the people and dwellings of the world. In the capital, lovely as if paved with jewels, houses of the high and low, their ridges aligned and roof tiles contending, never disappear however many ages pass, and yet if we examine whether this is true, we will rarely find a house remaining as it used to be. Perhaps it burned down last year and has been rebuilt. Perhaps a large house has crumbled and become a small one. The people living inside the houses are no different. The place may be the same capital and the people numerous, but only one or two in twenty or thirty is someone I knew in the past. One will die in the morning and another will be born in the evening: such is the way of the world, and in this we are like the foam on the water. I know neither whence the newborn come nor whither go the dead. For whose sake do we trouble our minds over these temporary dwellings, and why do they delight our eyes? This, too, I do not understand. In competing for impermanence, dweller and dwelling are no different from the morning glory and the dew. Perhaps the dew will fall and the blossom linger. But even though it lingers, it will wither in the morning sun. Perhaps the blossom will wilt and the dew remain. But even though it remains, it will not wait for evening.

In the more than forty springs and autumns that have passed since I began to understand the nature of the world, I have seen many unexpected things. I think it was on the twenty-eighth of the Fourth Month of Angen 3 [1177]. Around eight o’clock on a windy, noisy night, a fire broke out in the southeastern part of the capital and spread to the northwest. Finally it reached Suzaku Gate, the Great Hall of State, the university, and the Popular Affairs Ministry, and in the space of a night they all turned to dust and ash. The source of the fire is said to have been the intersection of Higuchi and Tominokōji, in makeshift housing occupied by bugaku dancers. Carried here and there in the violent wind, the fire spread outward like a fan unfolding. Distant houses choked on smoke; nearby, wind drove the flames against the ground. In the sky, ashes blown up by the wind reflected the light of the fire, while wind-scattered flames spread through the overarching red in leaps of one and two blocks. Those who were caught in the fire must have been frantic. Some choked on the smoke and collapsed; some were overtaken by the flames and died instantly. Some barely escaped with their lives but could not carry out their possessions. The Seven Rarities and ten thousand treasures all were reduced to ashes.62 How great the losses must have been. At that time, the houses of sixteen high nobles burned, not to mention countless lesser homes. Altogether, it is said that fire engulfed one-third of the capital. Thousands of men and women died, and more horses, oxen, and the like than one can tell. All human endeavors are foolish, but among them, spending one’s fortune and troubling one’s mind to build a house in such a dangerous capital is particularly vain.

Then, in the Fourth Month of Jishō 4 [1180], a great whirlwind arose near the intersection of Nakanomikado and Kyōgoku and raged as far as the Rokujō District. Because it blew savagely for three or four blocks, not a single house within them, large or small, escaped destruction. Some were flattened; some were reduced to nothing more than posts and beams. Blowing gates away, the wind carried them four or five blocks and set them down; blowing fences away, it joined neighboring properties into one. Naturally, all the possessions inside these houses were lifted into the sky, while cypress bark, boards, and other roofing materials mingled in the wind like winter leaves. The whirlwind blew up dust as thick as smoke so that nothing could be seen, and in its dreadful roar no voices could be heard. One felt that even the winds of retribution in hell could be no worse than this. Not only were houses damaged or lost, but countless men were injured or crippled in rebuilding them. As it moved toward the south-southwest, the wind was a cause of grief to many people. Whirlwinds often blow, but are they ever like this? It was something extraordinary. One feared that it might be a portent.

Then, in the Sixth Month of the same year, the capital was abruptly moved.63 The relocation was completely unexpected. According to what I have heard, Kyoto was established as the capital more than four hundred years ago, during the reign of the Saga emperor.64 The relocation of the capital is not something that can be undertaken easily, for no special reason, and so it is only natural that the people were uneasy with this move and lamented together about it. Objections having no effect, however, the emperor, the ministers, and all the other high nobles moved. Of those who served at court, who would stay behind in the old capital? Those who vested their hopes in government appointments or in rank, or depended on the favor of their masters, wasted not a day in moving, while those who had missed their chance, who had been left behind by the world, and who had nothing to look forward to, stayed sorrowfully where they were. Dwellings, their eaves contending, went to ruin with the passing days. Houses were disassembled and floated down the Yodo River as the land turned into fields before one’s eyes. Men’s hearts changed; now they valued only horses and saddles. No one used oxen and carriages any more. People coveted property in the southwest and scorned manors in the northeast. At that time I had occasion to go to the new capital, in the province of Tsu. I saw that there was insufficient room to lay out a grid of streets and avenues, the area being small. To the north, the city pressed against the mountains and, to the south, dropped off toward the sea. The roar of waves never slackened; a violent wind blew in off the saltwater. The palace stood in the mountains. Did that hall of logs look like this?65 It was novel and, in its way, elegant. Where did they erect the houses they had torn down day by day and brought downstream, constricting the river’s flow? Open land was still plentiful, houses few. Even though the old capital had become a wasteland, the new capital was yet unfinished. Everyone felt like the drifting clouds. Those who had lived here before complained about losing their land. Those who had newly moved here bemoaned the pains of construction. In the streets, I saw that those who should have used carriages rode on horses, and most of those who should have dressed in court robes and headgear wore simple robes instead. The ways of the capital had changed abruptly; now they were no different from the ways of rustic samurai. I heard that these developments were portents of disorder in the land, and it turned out to be so: day by day the world grew more unsettled and the people more uneasy, and their fears proved to be well founded, so that in the winter of the same year the court returned to this capital.66 But what became of all the houses that had been torn down? Not all of them were rebuilt as they had stood before.

I have heard that in venerable reigns of ancient times, emperors governed the nation with compassion: roofing his palace with thatch, Yao67 of China refrained from even trimming the eaves; seeing how thin the smoke that rose from the people’s hearths, Nintoku68 of Japan forgave even the lowest taxes. They did so because they took pity on the people and tried to help them. By measuring it against the past, we can know the state of the present.

Then, was it in the Yōwa era [1181–1182]?—long ago, and so I do not remember well, the world suffered a two-year famine, and dreadful things occurred. Droughts in spring and summer, typhoons and floods in fall—adversities followed one after another, and none of the five grains ripened. In vain the soil was turned in the spring and crops planted in the summer, but lost was the excitement of autumn harvests and of the winter laying-in. Consequently, people in the provinces abandoned their lands and wandered to other regions, or forgot their houses and went to live in the mountains. Various royal prayers were initiated and extraordinary Esoteric Buddhist rites were performed, to no effect whatever. It was the habit of the capital to depend on the countryside for everything, but nothing was making its way to the capital now. How long could the residents maintain their equanimity? As their endurance wore down, they tried to dispose of their valuables as if throwing them away, but no one showed any interest. The few who did engage in barter despised gold and cherished millet. Beggars lined the streets, their pleas and lamentations filling one’s ears. In this way, the first year struggled to a close. Surely the new year would bring improvement, one thought, but on top of the famine came an epidemic, and conditions only got worse. The metaphor of fish in a shrinking pool fit the situation well, as people running out of food grew more desperate by the day.69 In the end, well-dressed men wearing lacquered sedge hats, their skirts wrapped around their legs, went intently begging house to house. One would see them walking, exhausted and confused, then collapse, their faces to the ground. The corpses of people who had starved to death lay along the earthen walls and in the streets; their numbers were beyond reckoning. A stench filled the world, as no one knew how to dispose of so many corpses, and often one could not bear to look at the decomposing faces and bodies. There was not even room for horses and carriages to pass on the Kamo riverbed. As lowly peasants and woodcutters exhausted their strength, firewood, too, came to be in short supply, and so people with no other resources tore apart their own houses and carried off the lumber to sell at market. I heard that the value of what one man could carry was not enough to sustain him for a single day. Strangely, mixed in among the firewood were sticks bearing traces here and there of red lacquer, or of gold and silver leaf, because people with nowhere else to turn had stolen Buddhist images from old temples and ripped out temple furnishings, which they broke into pieces. I saw such cruel sights because I was born into this impure, evil age.70 There were many pathetic sights as well. Of those who had wives or husbands from whom they could not part, the ones whose love was stronger always died first. The reason is that putting themselves second and pitying the others, they gave their mates what little food they found. So it was that when parents and children lived together, the parents invariably died first. I also saw a small child who, not knowing that his mother was dead, lay beside her, sucking at her breast.

The eminent priest Ryūgyō of Ninna Temple,71 grieving over these countless deaths, wrote the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet on the foreheads of all the dead he saw, thereby linking them to the Buddha. Wanting to know how many had died, he counted the bodies he found during the Fourth and Fifth Months.72 Within the capital, between Ichijō on the north and Kujō on the south, between Kyōgoku on the east and Suzaku on the west, more than 42,300 corpses lay in the streets. Of course, many others died before and after this period, and if we include those on the Kamo riverbed, in Shirakawa, in the western half of the capital, and in the countryside beyond, their numbers would be limitless. How vast the numbers must have been, then, in all the provinces along the Seven Highways. I have heard that something of the sort occurred in the Chōjō era [1134], during the reign of Emperor Sutoku, but I do not know how things were then. What I saw before my own eyes was extraordinary.

Then—was it at about the same time?—a dreadful earthquake shook the land.73 The effects were remarkable. Mountains crumbled and dammed the rivers; the sea tilted and inundated the land. The earth split open and water gushed forth; boulders broke off and tumbled into valleys. Boats rowing near the shore were carried off on the waves; horses on the road knew not where to place their hooves. Around the capital, not a single shrine or temple survived intact. Some fell apart; others toppled over. Dust and ash rose like billows of smoke. The sound of the earth’s movement and of houses collapsing was no different from thunder. People who were inside their houses might be crushed in a moment. Those who ran outside found the earth splitting asunder. Lacking wings, one could not fly into the sky. If one were a dragon, one would ride the clouds. I knew then that earthquakes were the most terrible of all the many terrifying things. The dreadful shaking stopped after a time, but the aftershocks continued. Not a day passed without twenty or thirty quakes strong enough to startle one under ordinary circumstances. As ten and twenty days elapsed, gradually the intervals grew longer—four or five a day, then two or three, one every other day, one in two or three days—but the aftershocks went on for perhaps three months. Of the four great elements, water, fire, and wind constantly bring disaster, but for its part, earth normally brings no calamity. In ancient times—was it during the Saikō era [855]?—there was a great earthquake and many terrible things occurred, such as the head falling from the Buddha at Tōdai Temple,74 but, they say, even that was not as bad at this. Everyone spoke of futility, and the delusion in their hearts seemed to diminish a little at the time; but after days and months piled up and years went by, no one gave voice to such thoughts any longer.

All in all, life in this world is difficult; the fragility and transience of our bodies and dwellings are indeed as I have said. We cannot reckon the many ways in which we trouble our hearts according to where we live and in obedience to our status. He who is of trifling rank but lives near the gates of power cannot rejoice with abandon, however deep his happiness may be, and when his sorrow is keen, he does not wail aloud. Anxious about his every move, trembling with fear no matter what he does, he is like a sparrow near a hawk’s nest. One who is poor yet lives beside a wealthy house will grovel in and out, morning and evening, ashamed of his wretched figure. When he sees the envy that his wife, children, and servants feel for the neighbors, when he hears the rich family’s disdain for him, his mind will be unsettled and never find peace. He who lives in a crowded place cannot escape damage from a fire nearby. He who lives outside the city contends with many difficulties as he goes back and forth and often suffers at the hands of robbers. The powerful man is consumed by greed; he who stands alone is mocked. Wealth brings many fears; poverty brings cruel hardship. Look to another for help and you will belong to him. Take someone under your wing, and your heart will be shackled by affection. Bend to the ways of the world and you will suffer. Bend not and you will look demented. Where can one live, and how can one behave to shelter this body briefly and to ease the heart for a moment?

I inherited my paternal grandmother’s house and occupied it for some time. Then I lost my backing,75 came down in the world, and even though the house was full of fond memories, I finally could live there no longer,76 and so I, past the age of thirty, resolved to build a hut. It was only one-tenth the size of my previous residence. Unable to construct a proper estate, I erected a house only for myself.77 I managed to build an earthen wall but lacked the means to raise a gate. Using bamboo posts, I sheltered my carriage. The place was not without its dangers whenever snow fell or the wind blew. Because the house was located near the riverbed, the threat of water damage was deep and the fear of robbers never ebbed. Altogether, I troubled my mind and endured life in this difficult world for more than thirty years. The disappointments I suffered during that time awakened me to my unfortunate lot.78 Accordingly, when I greeted my fiftieth spring, I left my house and turned away from the world. I had no wife or children, and so there were no relatives whom it would have been difficult to leave behind. As I had neither office nor stipend, what was there for me to cling to? Vainly, I spent five springs and autumns living in seclusion among the clouds on Mount Ōhara.79

Reaching the age of sixty, when I seemed about to fade away like the dew, I constructed a new shelter for the remaining leaves of my life. I was like a traveler who builds a lodging for one night only or like an aged silkworm spinning its cocoon. The result was less than a hundredth the size of the residence of my middle age. In the course of things, years have piled up and my residences have steadily shrunk. This one is like no ordinary house. In area it is only ten feet square; in height, less than seven feet. Because I do not choose a particular place to live, I do not acquire land on which to build. I lay a foundation, put up a simple, makeshift roof, and secure each joint with a latch. This is so that I can easily move the building if anything dissatisfies me. How much bother can it be to reconstruct it? It fills only two carts, and there is no expense beyond payment for the porters.

Now, having hidden my tracks and gone into seclusion in the depths of Mount Hino,80 I extended the eaves more than three feet to the east, making a convenient place to break and burn brushwood. On the south I made a bamboo veranda, on the west of which I built a water-shelf for offerings to the Buddha, and to the north, behind a screen, I installed a painting of Amida Buddha,81 next to it hung Fugen,82 and before it placed the Lotus Sutra. Along the east side I spread soft ferns, making a bed for the night. In the southwest, I constructed hanging shelves of bamboo and placed there three black leather trunks. In them I keep selected writings on Japanese poetry and music, and the Essentials of Salvation. A koto and a biwa stand to one side. They are what are called a folding koto and a joined lute.83 Such is the state of my temporary hut. As for the location: to the south is a raised bamboo pipe. Piling up stones, I let water collect there. Because the woods are near, kindling is easy to gather. The name of the place is Toyama. Vines cover all tracks.84 Although the ravines are overgrown, the view is open to the west. The conditions are not unfavorable for contemplating the Pure Land of the West. In spring I see waves of wisteria. They glow in the west like lavender clouds. In summer I hear the cuckoo. Whenever I converse with him, he promises to guide me across the mountain path of death.85 In autumn the voices of twilight cicadas fill my ears. They sound as though they are mourning this ephemeral, locust-shell world. In winter I look with deep emotion upon the snow. Accumulating and melting, it can be compared to the effects of bad karma. When I tire of reciting the Buddha’s name or lose interest in reading the sutras aloud, I rest as I please, I dawdle as I like. There is no one to stop me, no one before whom to feel ashamed. Although I have taken no vow of silence, I live alone and so surely can avoid committing transgressions of speech.86 Although I do not go out of my way to observe the rules that an ascetic must obey, what could lead me to break them, there being no distractions here? In the morning, I might gaze at the ships sailing to and from Okanoya, comparing myself to the whitecaps behind them, and compose verses in the elegant style of the novice-priest Manzei;87 in the evening, when the wind rustles the leaves of the katsura trees, I might turn my thoughts to the Xunyang River and play my biwa in the way of Gen Totoku.88 If my enthusiasm continues unabated, I might accompany the sound of the pines with “Autumn Winds” or play “Flowing Spring” to the sound of the water.89 Although I have no skill in these arts, I do not seek to please the ears of others. Playing to myself, singing to myself, I simply nourish my own mind.