The late medieval period extends from the beginning of the Kenmu restoration (1333–1336) to the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, roughly 270 years that can be further subdivided into the Northern and Southern Courts (Nanboku-chō) period (1336–1392), the Muromachi period (1392–1573), and the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1573–1598).

In 1333 the Kamakura shogunate was overthrown by warrior forces that rallied to the royalist cause of Emperor GoDaigo (r. 1318–1339). GoDaigo saw the overthrow of the Kamakura shogunate as a mandate to revive what he believed to be the direct imperial rule that had existed before the rise of the Fujiwara regents in the mid-Heian period, the powerful retired emperors in the late Heian period, and the bakufu (military government) in the Kamakura period. The “imperial restoration,” known as the Kenmu restoration, lasted for only three years, until 1336, when a struggle broke out between Nitta Yoshisada (1301–1338) and Ashikaga Takauji (1305–1358), the leaders of two branches of the Minamoto, both of whom had initially rallied to GoDaigo’s cause. In 1336 Takauji defeated Yoshisada and captured Kyoto. GoDaigo fled to Yoshino, in the mountains to the south. Takauji then had a member of another branch of the imperial family named as emperor in Kyoto, making two emperors, one in the north (Kyoto) and one in the south (Yoshino), a situation that was not resolved until 1392 when the two lines were rejoined. Meanwhile, Takauji established a new shogunate, known later as the Ashikaga or Muromachi shogunate (1336–1573), with its offices in the Muromachi quarters of Kyoto.

The sixty years of the Northern and Southern Courts was probably the bloodiest period in Japanese history. The depth of its chaos and internal conflict are vividly depicted in the Taiheiki (1340s–1371), a military history that bears the seemingly ironic title Chronicle of Great Peace. Nonetheless, despite the constant bloodshed and upheaval, a new culture emerged. A new form of poetry, renga (classical linked verse), led by Nijō Yoshimoto (1320–1388), became popular; historical chronicles written in the vernacular appeared; Zen priests wrote their finest kanshi (Chinese) poetry; kyōgen (comic drama) were performed; and nō theater was first established as a high art form by Kan’ami (1333–1384).

Noteworthy among the historical chronicles of the Nanboku-chō period are The Clear Mirror (Masukagami, 1338–1376), which recounts the history of the Kamakura period, especially the Jōkyū rebellion (1221), which resulted in Emperor GoToba’s exile, and Kitabatake Chikafusa’s Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns (Jinnō shōtōki, 1339, 1343), which, under the influence of Ise Shinto, argues for the legitimacy of the imperial succession from the perspective of the Southern Court. But the outstanding military chronicle is the Taiheiki, a history of the throne and the different samurai houses involved in the turmoil of the Northern and Southern Courts period. The Taiheiki was recited widely, and beginning in the Muromachi period, it had a great impact on popular culture.

Until the thirteenth century, renga (linked verse) had been monopolized by court aristocrats, but from the end of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), it suddenly spread to samurai, temple-shrines, and commoners across the country. In response to this new market, texts like the Tsukuba Collection (Tsukubashū, 1356), an anthology of renga edited by Nijō Yoshimoto, one of the leading intellectuals and poets of the day, were compiled.

The Muromachi period—named after the Ashikaga clan that established the bakufu, or military government, in Muromachi, a section of Kyoto—lasted for about 180 years, from 1392, when the two imperial courts were unified, to 1573, when Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) drove out the fifteenth and last Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki (1537–1597). The latter half of the Muromachi period is sometimes referred to as the Sengoku (Warring States) period (1467–1573), beginning with the Ōnin war (1467–1477) and ending with the unification of the country under Oda Nobunaga in 1573. The Azuchi–Momoyama period, when Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) held control of the country, began with the fall of the Muromachi shogunate in 1573 and ended with the battle of Sekigahara, which unified the country in 1600 under Tokugawa Ieyasu and ushered in the Tokugawa, or Edo, period.

During the Northern and Southern Courts period, classical court culture gradually disappeared, replaced by the rise of linked verse (pioneered by Nijō Yoshimoto and others), the flourishing of Chinese poetry by Zen monks, and the emergence of nō drama, kyōgen, and such dance (mai) forms as kowakamai (ballad drama). These dramatic forms prospered in the Muromachi period and were patronized by and became the favorite pastimes of powerful domain lords and shoguns. Otogi-zōshi (the narrative successor to monogatari and setsuwa) and kouta (little songs) were popular as well. Theories of art and drama became highly developed during the Muromachi period, with Zeami’s (1363?–1443?) and Zenchiku’s (1405?–1470?) treatises on nō drama, Shōtetsu’s (1381–1459) treatise on waka, and Sōgi’s (1421–1502) and Shinkei’s (1406–1475) writings on renga. The short Azuchi–Momoyama period represents a transition to the Tokugawa or early modern period, in which sekkyō-bushi (sermon ballads) were popular and jōruri (puppet theater) and kabuki first appeared. In the late medieval period, haikai (popular linked verse) and renga (classical linked verse) found large audiences, and by the seventeenth century, haikai had become the most widely practiced literary genre in Japan. In 1549 the Jesuit order (Societas Jesu, J. Yasokai), which was founded in 1540, sent missionaries to Japan, and they brought with them Western culture and produced a romanized version of Aesop’s Fables.

The Muromachi bakufu came of age with the third shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (r. 1368–1394), who unified the Northern and Southern imperial courts. Yoshimitsu was also a great patron of the arts and is especially remembered for the retreat that he built at Kitayama, north of the capital, and for the construction of the Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion). The cultural efflorescence under Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and his son Ashikaga Yoshimochi, the fourth shogun (r. 1394–1423), is referred to as Kitayama culture. In the Muromachi period, both nō and kyōgen matured into major genres, particularly under the leadership of Zeami, whose patron was Yoshimitsu. Another notable period of cultural activity was the so-called Higashiyama period, in the latter half of the fifteenth century, primarily during the rule of Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490, r. 1449–1473), the eighth shogun. In 1483 he built a retreat at Higashiyama (the Ginkaku-ji, or Silver Pavilion), where he led an elegant life and supported nō drama, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, renga, and landscape gardening. Higashiyama culture, as it is called, is noted for its fusion of warrior, aristocratic, and Zen elements, particularly the notions of wabi and sabi, which found beauty and depth in minimalist, seemingly impoverished, material.

The origins of nō drama were the sarugaku (literally, “monkey/comic art”) schools associated with shrines and temples (such as the Kasuga Shrine) in Ōmi and Yamato Provinces. The actors belonged to groups attached to private estate owners (ryōshu) and large temples and shrines in the Kinai region (Yamato, Yamashiro, Kawachi, Izumi, and Settsu Provinces). A number of nō plays are based on engi-mono, stories about the origins of local gods. During the Northern and Southern Courts period, when nō and kyōgen matured, Kan’ami (1333–1384) and Zeami were being patronized by the Ashikaga shogunal family, which stood at the apex of power. At that point, nō and kyōgen broke away from their earlier dependence on temples and shrines and from their function as religious performances supporting the private estate system. Of particular interest here is that in their mature phase, nō and kyōgen, which had developed in the provinces as commoner entertainment, now were the province of the Muromachi military government, situated in the capital, which was actively absorbing the court culture. At this time, nō reflected Heian court culture and aesthetics and developed the aesthetics of yūgen (mystery and depth), which included evocations of the classical past. Characteristic of this phase of nō was the woman play (katsura mono), including plays about characters from The Tales of Ise and The Tale of Genji. Despite first taking shape in the provinces and outside the central spheres of power, nō now was helping enforce the authority of the center, of the Muromachi bakufu, and of the revival of imperial court culture.

From the latter half of the thirteenth century and peaking in the fourteenth century, Song and Yuan Zen culture was imported into the world of the shrines and temples in both Kamakura and Kyoto. Zen Buddhism influenced such art forms as dry stone gardens (karesansui), monochromatic ink-painting, Chinese poetry (kanshi), and tea ceremony. Using the Chinese cultural forms that the Zen institutions had imported, the temples and shrines created a new culture distinct from that established by the Heian court aristocrats.

Likewise, samurai culture used Zen culture to transform itself. Until the thirteenth century—despite the outstanding samurai waka poets like Minamoto Sanetomo (1192–1219); the third Kamakura shogun (r. 1203–1219), who produced the Poetry Collection of the Minister from Kamakura (Kinkaishū), in a neo-Man’yōshū style; and the bakufu rituals imitating those of the Kyoto nobility—they all remained within the framework of aristocratic culture. Then, beginning in the latter half of the thirteenth century, when the bakufu had as much authority as the imperial court, the samurai slowly began to produce their own culture, particularly through the medium of Zen. The bakufu invited Zen intellectual leaders to Kamakura, and under its patronage the Zen priests imported texts and utensils from Song and Yuan China. After the Northern and Southern Courts period, this Zen-inspired samurai culture developed rapidly, creating a distinctive culture that was more than merely an imitation of Zen culture.

THE RISE OF PROVINCIAL CULTURE

One of the main characteristics of the late medieval period is that the various genres that had originated in Heian court culture—the imperial anthologies of Japanese poetry (chokusenshū), the vernacular court tales (monogatari), and women’s court diaries (nikki)—and that had continued to flourish in the Kamakura period, almost completely died out. The editing and collecting of setsuwa (anecdotes), which were popular in the late Heian and Kamakura periods, also ended with the compilation of the Records of Three Countries (Sangoku denki), in the first half of the fifteenth century.

Perhaps one of the most salient characteristics of the Muromachi culture was its focus on commoner life and values in the provinces. In the late Heian period, setsuwa collections such as the Tales of Times Now Past (Konjaku monogatari shū, ca. 1120) provided a window onto life in the provinces, but the values remained largely those of the capital and the aristocracy. But in the late medieval period, the perspectives of the provinces and of the commoners formed a counterbalance to those of the capital and aristocrats.

At the beginning of the medieval period, the establishment of the bakufu, the seat of the military government, in the east in Kamakura, far from the capital, had a great impact on medieval culture. Although cultural activity continued to be centered in Kyoto, a new community of intellectuals gathered in Kamakura, making it a separate cultural center. The spread of culture outside the capital increased dramatically during the Warring States period (1467–1573). The Ōnin war (1467–1477), which arose over an inheritance issue involving the Ashikaga shogun and which pitted daimyō (military lords) from the west against those in the east, took place mainly in Kyoto and destroyed the city, leading aristocrats and cultural figures to flee to the provinces.

The rise of a new culture was closely related to the development of roads and travel, the reasons for which are various. Many people wanted to escape the ravages of war, and the aristocracy, particularly after being driven out of the capital during the Ōnin war, sought the patronage of wealthy provincial lords. Buddhist and Shinto followers frequently went on pilgrimages to shrines and temples, the most famous of which was the pilgrimage to Ise Shrine. Various religious groups—such as monks from Mount Kōya (Kōya hijiri), monks soliciting donations for temple building (kanjin hijiri), and nuns (bikuni)—also traveled, as did biwa hōshi (lute-playing minstrels), etoki (picture storytellers), nō actors, kyōgen players, and puppeteers (tekugutsu). Renga masters, who often were half layperson and half priest, also traveled to compose with different groups throughout the country, to give lessons on the Japanese classics, and to inspire their own poetry.

The culture of the capital was thus carried to the provinces while the culture of the provinces was brought to the capital, giving new life to both. This interaction of oral and written, aristocratic and commoner, led, particularly in the late medieval period, to the juxtaposition of the elegant, refined sensibility (ushin) and the common or popular (mushin), the serious and the comic, the elite and the popular—what in the Tokugawa period was called ga (high) and zoku (low). This dialectic is evident in the relationship of nō to kyōgen, and of renga (classical linked verse) to haikai (popular linked verse). Sometimes a commoner genre (such as sarugaku, a form of mime) evolved into an elite genre like nō, shedding its comic, vulgar, or commoner roots. Sometimes, however, a genre continued to cultivate its own popular base (as with kyōgen and haikai).

Nō drama consists of dance, song, and dialogue and is traditionally performed by an all-male cast. Sometime in the late Kamakura period (1192–1333), sarugaku (literally, “monkey/comic art”), a performance art that includes comic mime and skits, evolved into nō drama. Sarugaku troupes served at temples, and it is believed that their roles in religious rituals have been preserved in the oldest and most ritualistic piece in the current nō repertoire, Okina (literally, Old Man), in which the dances of deities celebrate and purify a world at peace.

By the mid-fourteenth century, nō had gained wide popularity and was performed not only by sarugaku but also by dengaku troupes. Dengaku had originally been a type of musical accompaniment to the planting of rice, but its troupes came to specialize in acrobatics and dance as well. In the late fourteenth century, a period of intense competition (among troupes and between sarugaku and dengaku), the Kanze troupe, a sarugaku troupe from Yamato Province (now Nara Prefecture), led first by Kan’ami (1333–1384) and later by his son Zeami (1363?–1443?), shaped the genre into what is seen on today’s stage.

Kan’ami attracted audiences with his rare talent as a performer and a playwright. Among his innovations was the introduction of the kusemai, a popular genre combining song and dance, in which the dancing performer rhythmically chants a long narrative. By incorporating the rhythms of kusemai singing into his troupe’s performances, Kan’ami transformed the hitherto rather monotonous nō chanting into a more dramatic form, one that became very popular and was soon emulated by other sarugaku and dengaku troupes.

In 1374, Kan’ami’s growing popularity finally inspired the seventeen-year-old Yoshimitsu (1358–1408, r. 1368–1394), the third Ashikaga shogun, to attend a performance by Kan’ami’s troupe in Imagumano (in eastern Kyoto). From that time on, the young shogun became a fervent patron of Kan’ami’s troupe. Yoshimitsu also was charmed by a beautiful boy actor, the twelve-year-old Zeami. Zeami soon began serving the shogun as his favorite page, mixing with court nobles and attending linked-poetry (renga) parties and other cultural events. After Kan’ami’s death, however, Yoshimitsu’s patronage shifted from Zeami, now a mature nō performer and the head of his own troupe, to Inuō (also known as Dōami, d. 1413), a performer in a sarugaku troupe from Ōmi Province (now Shiga Prefecture). Inuō had gained a reputation for his “heavenly maiden dance” (tennyo-no-mai), an elegant dance that was said to epitomize yūgen, a term signifying profound and refined beauty and the dominant aesthetic among upper social circles.

In order to maintain the shogun’s favor, Zeami had to keep producing new plays and reforming his troupe’s performing style in accordance with shifting aesthetic trends. Zeami’s plays, of which he wrote nearly forty (or more than fifty, if his revisions of existing plays are included), are marked by exquisite phrasing and frequent allusions to Japanese classical texts. In addition, Zeami incorporated Inuō’s elegant dance into his own plays, even though his troupe had originally specialized in wild demon plays and realistic mimicry. In an effort to adjust his troupe’s performances to the principle of yūgen, Zeami created plays with elegant dances and refined versification, which poetically represented aristocratic characters often drawn from Heian monogatari. In his twenty or so theoretical treatises on nō, he also emphasized the importance of using yūgen in every aspect of nō.

Another of Zeami’s innovations was the mugen-nō (dream play or phantasmal play), which typically consists of two acts. In the first, a traveler (often a traveling monk) meets a ghost, a plant spirit, or a deity, who, in the guise of a local commoner, recalls a famous episode that took place at that location, and in the second act, the ghost, spirit, or deity reappears in its original form in the monk’s dream. The ghost usually recalls a crucial incident in its former life, an incident that is now causing attachment and obstructing its path to buddhahood. By reenacting that incident, the ghost seeks to gain enlightenment through the monk’s prayers. The focus of these plays thus is less on the interaction between the characters than on the protagonist’s emotional state.

Ashikaga Yoshinori (Yoshimitsu’s son), who became the sixth Ashikaga shogun in 1429, favored Zeami’s nephew On’ami, eventually placing him at the head of the Kanze troupe. With the loss of the shogun’s patronage, Zeami’s second son took the tonsure and left the theater. His elder son Motomasa, the author of Sumida River (Sumidagawa) and Zeami’s last hope, died in 1432, in his early thirties. In 1435 Zeami was exiled to Sado, a remote island in northeastern Japan. The year of his death is not certain, nor is it known whether he died on Sado or was pardoned and permitted to return to Kyoto.

After his death, Zeami’s plays were recognized as central to the repertoire and were followed especially faithfully by Zeami’s son-in-law Zenchiku (1405?–1470?), the author of Shrine in the Fields (Nonomiya). In the late Muromachi period, following the Ōnin war (1467–1477), audiences began to exhibit a taste for different types of nō, spurring the creation of more spectacular plays, such as those depicting dramatic events occurring in the present (for example, Ataka) and often featuring realistic battle scenes.

Nō became especially popular among the warrior class. When Tokugawa Ieyasu founded his shogunate in Edo in 1603, he bestowed his official patronage on four sarugaku troupes: Kanze, Hōshō, Konparu, and Kongō, all from Yamato (later the Kita troupe was added). As a result, only those performers affiliated with these four (or five) troupes were officially allowed to perform nō. It also became customary among provincial lords (daimyō), following the shogun’s lead, to employ performers of official nō troupes, who performed on ceremonial occasions. One of the direct outcomes of this ceremonialization of nō was a lengthening of performance times, as a result of which the plays came to be performed with much more rigorous precision. The intention was not to bring nō into line with changing trends but to preserve and refine the established plays and performance styles.

Although around 2,000 nō plays still exist, the current repertoire consists of only about 240 plays, most of which were written between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. And even today, many of the most frequently performed plays are those written by Zeami.

The shite, or protagonist, is often a supernatural being such as a ghost, plant spirit, deity, or demon. Most nō plays center on the shite’s words and deeds—that is, his or her telling of a story, usually about the shite’s own past, in the form of a monologue and dance. The characters subordinate to the shite are called shite-tsure (companions to the shite) or simply tsure. In two-act plays, the shite in the first act is called the mae-shite (or mae-jite [shite before]), and in the second act, the nochi-shite (or nochi-jite [shite after]). The nochi-shite usually appears in a different costume, signifying the revelation of his or her true identity, and sometimes even as a different character altogether.

The waki is the character opposite—although not necessarily antagonistic to—the shite. When the shite is a supernatural being, the waki is usually a traveling monk who listens to the shite’s retelling of the past. But when the shite is a living warrior, the waki is most often a warrior of the opposing camp. Unlike the shite, the waki is always a living person. The characters subordinate to the waki, often their retainers or traveling companions, are called waki-tsure (or waki-zure). The ai or ai-kyōgen is a minor character in a nō play, such as a local villager, who might provide the waki, and thus the audience, with a relatively colloquial, prose recapitulation of what the shite has already recounted in poetry. In some plays, especially those written in the late Muromachi period, comical characters appear during the acts as, for example, in Ataka. These characters are also called ai.

The chorus consists of six to ten members who sit motionless throughout the play on the right side of the stage and do not have a specific role in the play. Sometimes they chant the words of one or another of the characters, and at other times they describe the scene. The main nō stage is a square about nineteen by nineteen feet. During a performance, the actors usually enter and exit the stage along the bridgeway (hashigakari) to the left. Nō never uses painted scenery or backdrops. The setting is depicted only verbally, and many plays have no stage props at all. Others have only a symbolic prop used for the most significant element of a play’s setting. When placed on the bare stage, this prop attracts the audience’s attention and becomes the play’s focal point. The characters sometimes hold swords, rosaries, or willow boughs that signify that the holder is crazed (as with the mother in Sumida River). All performers carry fans, which are sometimes used as substitutes for other props, such as a writing brush, a saké flask, or a knife.

Most actors wear masks, although the waki and waki-tsure, who always portray living male characters, never do. A performer without a mask must never show any facial expression or use makeup; he is expected to use his own face as if it were a mask. Except for some masks that are made for specific characters (such as the shite’s mask in Kagekiyo), most masks represent generic types. For example, waka-onna masks, which show a young female face, are used for both the female saltmaker in Pining Wind (Matsukaze) and Lady Rokujō in Shrine in the Fields.

Demon masks, with their ferocious faces and large, protruding eyes, express fierce supernatural power, while masks of human characters (including ghosts), whose feelings and emotions are often the focus of a play, usually display a static and rather neutral expression instead of a specific emotion. These masks are paradoxically said to be both “nonexpressive” and “limitlessly expressive,” since the expression appears to change according to the angle of a performer’s face. The actor’s unchanging “face” also encourages audience members to project onto his mask the emotional content that they detect from the chanting. Interestingly, the nō masks are slightly smaller than the human faces they cover, revealing the tip of the performer’s lower jaw and thus disrupting the audience’s full immersion in dramatic illusion.

Nō costumes are famous for their splendor and exquisite beauty. Most are made of stiff, heavy materials that are folded around the performer’s body like origami. A lighter kimono, made from a translucent fabric and with long, wide sleeves, is sometimes worn over these costumes. Thus, just as masks conceal the actor’s facial individuality, so the costumes conceal his physical individuality. The beauty and expressiveness of his performance thus are not in the particular features of his own face and body but in the grace and expressiveness of his movements.

Movements on the nō stage are strictly choreographed and are generally very slow and highly stylized. Weeping, for example, is expressed merely by slowly lifting one hand toward the eyes and then lowering it again. This strict economy of movement infuses each gesture with meaning. One step forward can express joy, resolution, or any other feeling that seems to fit the context. The fundamental basis for the dances and gestures of nō is the standing posture (kamae) and a stylized manner of walking called hakobi. Shite actors play characters of both sexes, with gender expressed by subtle variations of the angles of the performer’s limbs and, above all, by the way he stands and walks. Differences in age, social status, and mental state are indicated similarly. Because so much emphasis is placed on a simple movement like walking, nō has often been characterized as “the art of walking.”

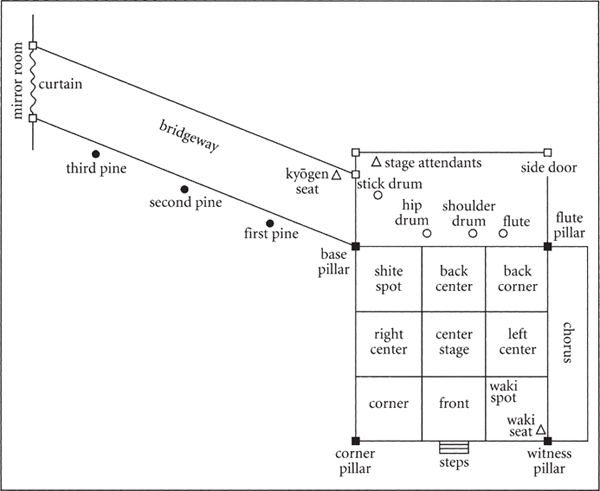

Diagram of a nō stage.

Dance in nō is performed to musical accompaniment, by either the musicians alone or the musicians and chorus together. In many plays, dances set to the chanting of the chorus appear in the kuse section and at the end of the play. The dance in the kuse section consists mostly of abstract movements. Because they do not have any fixed meanings, dances can be interpreted according to the general context or to that of the lines that accompany them, in much the same way that a single nō mask can project a broad range of emotions. By contrast, the dance at the end of the play usually includes many specifically representational movements that mimetically render the words of the text. Dances set to instrumental music generally are abstract as well and usually are similar in both movement and music. The same series of movements can appear in a rapid, exuberant “deity dance” (kami-mai), an elegant and gentle dance (chū-no-mai), or a tranquil and meditative dance (jo-no-mai), depending on the tempo and mood of otherwise very similar music. As with the masks, these dances, too, are generic. The same chū-no-mai, for example, is performed by a noble youth in Atsumori and by the female saltmaker in Pining Wind.

The chanting styles of nō are divided into speech (kotoba) and song (fushi), with the speech actually more intoned than spoken. Song can be further subdivided into “congruent song” (hyōshi ai), which is chanted in a steady rhythm, keeping precise time with the drums, and “noncongruent song” (hyōshi awazu), which incorporates prolonged grace notes into important phrases and is not chanted in measured time. There also are two modes of singing: a “dynamic mode” (tsuyogin or gōgin) and a “melodic mode” (yowagin or wagin). The dynamic mode is generally used for the roles of warriors and demons, and the melodic mode is reserved for female and elderly roles. In many plays, however, the same character may use both modes. For example, in Kiyotsune, even though the shite chants mainly in the dynamic mode, he frequently switches to the melodic mode (in segments indicated, for example, as ge-no-ei, kakeai, jō-no-ei, or uta) in order to convey two different aspects of the same character: warrior and loving husband.

Except for the preceding modes, which were introduced only after the Tokugawa period, the distinctions in chanting styles, as well as the rhythmic patterns and the degree of regularity of the syllabic meter, are necessary for distinguishing subsections (shōdan) of plays. In the following translations, the names of subsections are indicated in parentheses preceding the text. Each subsection has its own pattern of musical structure and/or content, which remains consistent from play to play. For example, the subsection called the nanori is a self-introduction by a character and is chanted mostly in the speech style, while a kuse is a congruent song with narrative elements that starts in a lower register and then moves to a higher one.

Instrumental music accompanies the dances and some of the chanting, as well as the entrance and exit of the characters. The music is provided by one flute and three different types of drums, each played by a single musician. With this dominance of percussion instruments, the music of nō consists more of silence than of sound. In fact, silence (ma [“interval” or “gap”]) is traditionally regarded as the principal element of nō music. The sounds of the instruments, as well as the intermittent cries of the drummers, are introduced in order to interrupt the flow of time in nō plays and to make the silence between sounds all the more noticeable.

Among the several ways in which nō plays are categorized, the one most widely used today is the “five categories,” which generally are differentiated according to the type of shite. The first category is the “deity play” (waki-nō or kami-nō), in which a deity explains the origin of a shrine, or a related legend, and celebrates the peaceful reign of an emperor. The second is the “warrior play” (shura-nō), in which the ghost of a warrior, now tormented in the hellish realm of constant battle known as the shura realm, reenacts a battle scene from his previous life. The third is the “woman play” (kazura-mono), whose protagonists are mostly elegant female figures, including the ghosts of women or female plant spirits. The “fourth-category plays” (yobanme-mono), also referred to as “miscellaneous plays” (zō mono), include all plays that do not fit into any of the other four categories, including plays about mad people, living warriors, or the spirits of the dead who linger in this world because of their excessive attachments. The fifth category is “demon plays” (oni-nō), also called “ending plays” (kiri-nō), in which the protagonists usually are demons.

This categorization scheme originated in the late seventeenth century. From that time until the present, a formal program for a nō-play performance usually includes one play from each of the five categories, performed in the preceding order, with a kyōgen play between each nō play. Today, however, performances in this full formal configuration are staged only on special occasions, such as New Year’s Day.

Many nō plays draw on and allude to classical texts like The Tales of Ise, The Tale of Genji, or folk legends of such famous figures as Ono no Komachi. Since classical texts were largely disseminated through medieval commentaries, many plays also reflect contemporary interpretations of their source material. In addition, playwrights often introduced their own new twists to familiar narratives. Indeed, the mugen-nō structure gave playwrights the perfect format for such reinterpretations, as famous episodes could be subjectively reconstrued through the personal recollections of a ghost.

Nō plays are also interlarded with citations from famous poems and classic tales. Atsumori, for example, offers an analogy between its eponymous hero, who is a character from The Tales of the Heike, and the protagonist of The Tale of Genji; similarly, the crazed mother in Sumida River compares herself with the nobleman protagonist of The Tales of Ise. Such heavy dependence on classical allusions is especially noticeable in Zeami’s and Zenchiku’s plays and suggests an audience with a high level of literary erudition. In fact, the most popular literary activity at the time in high society—also practiced, to some extent, even among commoners—was the composition of linked verses (renga), which required the participants to allude constantly to a wide range of earlier literary works. It was in such a cultural milieu that nō developed.

The following plays are presented in chronological order, so as to give some sense of the historical development of the genre.

[All nō introductions by Akiko Takeuchi]

Subsections

According to Styles

Primary Speech Styles

katari | story narration |

yomimono | recitation |

mondō | question and answer |

nanori | self-introduction |

tsuki-zerifu | arrival speech |

Noncongruent Song Styles | |

ei | chanted poem |

ge-no-ei | waka recited in the lower register |

jō-no-ei | waka recited in the upper register |

issei | song in regular 7/5 meter mostly in the upper register, typically chanted right after the entrance of a character |

kakeai | segment chanted alternately by two characters |

kudoki | song sung mostly in the lower register, expressing lament or sorrow |

kuri | short segment sung mostly in the high register, incorporating the highest pitch (also called kuri) and prolonged grace notes |

kudoki-guri | kuri just before kudoki |

nanori-guri | kuri that delivers a character’s self-introduction |

sashi | song that starts in the upper register, narrating a scene in a relatively plain rhythm and melody |

waka | recitation of a waka just after a dance |

Congruent Song Styles | |

uta | song in regular 7/5 meter |

age-uta | song sung in the upper and middle registers |

sage-uta | song sung in the middle and low registers |

dan-uta | song starting in the fashion of age-uta but developing into a different pattern |

chū-noriji | song sung in vigorous chū-nori rhythm, in which each syllable matches a half beat; typically used in the ending scene of a warrior play |

kiri | simple song sung in the middle register with almost no grace notes, at the end of a play |

kuse | song with narrative elements, which starts in the low register and then moves to a higher one |

song sung in ōnori rhythm, characterized by an especially steady, rhythmical beat, with each syllable lasting a whole beat | |

rongi | segment chanted alternately by characters (or a character and a chorus) |

shidai | short song in regular meter, starting in the upper register and ending in the lower one |

Subsections that do not fit the preceding categories are listed as “unnamed.”

Anonymous, revised by Zeami

Lady Aoi is the oldest of the numerous nō plays that draw on The Tale of Genji. In the nō treatise Conversations on Sarugaku (Sarugakudangi), Zeami recalls watching the play performed by Inuō (d. 1413), a senior sarugaku performer from Ōmi Province. The text included here is probably Zeami’s revision of a play that was originally written for Inuō’s troupe.1 Since the play still preserves what are regarded as basic characteristics of nō theater from Ōmi Province—such as a female demon as the protagonist and a struggle between a monk and a vengeful spirit—Zeami’s contribution was probably rather minor and may have been largely limited to refinements in phrasing.

The play is based on a famous episode in The Tale of Genji, in the “Heartvine” (Aoi) chapter, in which the young Genji has an affair with Lady Rokujō, a widow of the late crown prince known for her sophistication and beauty. Before long, his visits to her become less frequent, and she feels deeply wounded, particularly since their relationship has come to be widely known. Nevertheless, on the day before the Kamo Festival, she decides to view the procession, hoping to secretly glimpse Genji. In order to conceal her identity, she appears in an inconspicuous carriage, which is roughly pushed to the back of the crowd by Aoi’s drunken male attendants (who do in fact recognize Rokujō) to give their own mistress a front-row view. Genji passes Rokujō without noticing her half-wrecked carriage, instead acknowledging Lady Aoi, his principal wife, who is pregnant with his first child. Soon thereafter, Aoi is possessed by an evil spirit, which later kills her shortly after she has given birth to Genji’s son. The evil spirit turns out to be the jealous and vengeful spirit of Lady Rokujō, which, without her conscious knowledge, had wandered from her body and attacked her rival.

In the first act of the play, Teruhi, a shaman who summons “possessing spirits” (mononoke) with the twanging of a bow, identifies the possessing spirit as that of Lady Rokujō. In the second act, the holy man of Yokawa, a renowned mountain ascetic, dispels the possessing spirit. A careful comparison with Genji reveals how freely the play has adapted its original material. There is scarcely any direct citation from the original text except in one section (the kudoki), which refers to some well-known chapter titles. Aoi’s pregnancy, one reason for her vulnerability and for Rokujō’s jealousy, is not mentioned at all in the play. The shaman does not appear in the original, in which the spirit of Lady Rokujō speaks with Aoi’s voice directly to Genji and various monks. Neither does the mountain ascetic play a significant role in the original. In Genji, the spirit, far from being conquered by a monk, finally succeeds in killing Aoi, and even after Rokujō’s own death, her spirit continues to torment and kill Genji’s other wives.

Several tales contemporaneous with this play depict exorcisms of vengeful spirits in a surprisingly similar manner, suggesting that the play followed an existing pattern of exorcism tales and borrowed the names of characters from Genji. On the one hand, because the text of Genji was largely inaccessible to the general population, the play is written in such a way as to entertain even those who might not be familiar with the original. On the other hand, the text of the play repeatedly refers to a carriage and to the humiliation associated with it (without recounting the incident itself), which allows those familiar with the original Genji episode to appreciate these cryptic allusions to Lady Rokujō’s carriage.

In early performances of the play, a carriage was used as a stage prop, with a weeping young lady-in-waiting clinging to its shaft. Later, both the carriage and the lady-in-waiting were omitted, giving rise to certain discrepancies between the text and the action on stage. For example, although Lady Rokujō appears alone on stage, the shaman refers to a weeping lady-in-waiting. Moreover, in the mondō section, the shaman sympathizes with Rokujō and joins her in tormenting Aoi. Originally, it was presumably the lady-in-waiting, not the shaman, who chanted this section and acted as Rokujō’s accomplice. The reason for eliminating the lady-in-waiting and the carriage is not entirely clear, but it may have been to avoid the difficult task of getting both of them off the stage without disrupting the performance.

In the first act, the performer who plays Lady Rokujō wears a deigan mask, whose golden eyes indicate her repressed jealousy. In the second act, he wears a hannya, a mask of a woman with two horns and a wide mouth, signifying that her spirit has now been transfigured into a demon. On stage, Aoi herself is represented only by a folded kimono. This stage prop is said to have inspired William Butler Yeats, who used a similarly folded cloth to symbolize the well in his nō-inspired play At the Hawk’s Well. The following translation is based on the current text of the Kanze school.

Characters in Order of Appearance

TERUHI, a shaman (ko-omote mask) | tsure |

A COURTIER in the service of Emperor Suzaku | waki-tsure |

VENGEFUL SPIRIT OF LADY ROKUJŌ in the form of a noblewoman (deigan mask) | mae-shite |

ai | |

THE HOLY MAN of Yokawa | waki |

LADY ROKUJŌ as an evil spirit (hannya mask) | nochi-shite |

Place: Mansion of the minister of the left in the capital

Act 1

Stage attendant places toward the front of the stage an embroidered kosode kimono, which represents Lady Aoi on her sickbed. Teruhi, wearing a ko-omote mask, wig, gold-patterned underkimono, brocade outer kimono, and white wide-sleeved robe, and the Courtier, wearing a cavity cap, heavy silk kimono, lined hunting robe, and white wide divided skirt, appear, cross the bridgeway, and enter the stage. Teruhi sits at the waki spot, and the Courtier stands at the shite spot.

COURTIER: (nanori) I am a courtier in the service of Emperor Suzaku.2 The demon that has possessed Lady Aoi, daughter of the minister of the left, is intransigent. His Lordship has invited the most revered and eminent priests to perform secret and solemn rites of exorcism as well as cures. They have tried everything but to no avail. I have been ordered to call in Teruhi, a shaman, who is known far and wide for her skill in birch-bow divination. She will ascertain by the bow whether the evil spirit is that of a living or a dead person. I shall ask her.

Teruhi faces the kosode kimono and, to azusa music, chants an incantation for calling forth an evil spirit.

TERUHI:

(unnamed) May Heaven be cleansed,

May Earth be cleansed,

May all be cleansed within and without,

The Six Roots, may they all be cleansed.3

(jō-no-ei) Swiftly, on a dapple gray horse,

Comes a haunting spirit

Tugging at the reins.

To issei entrance music, the spirit of Lady Rokujō, wearing a mask with gold-painted eyes, long wig, serpent-scale-patterned underkimono, embroidered outer kimono in the koshimaki style, and brocade outer kimono in the tsubo-ori style, appears, advances along the bridgeway, and stops by the first pine.

(issei) Riding the Three Vehicles of the Law,

Others may escape the Burning House.4

Mine is but a cart

In ruins like Yūgao’s house;5

I know not how to flee my passions.6

(Enters the stage and stands in the shite spot.)

(shidai) Like an ox-drawn cart, this weary world,

Like an ox-drawn cart, this weary world

Rolls endlessly on the wheels of retribution.

(sashi) Like the wheels of a cart forever turning

Are birth and death for all living things;

Through the Six Worlds7 and the Four Births8

You must journey;

Strive as you will, there is no escape.

What folly to be blind

To the frailty of this life,

Like the banana stalk without a core,

Like a bubble on the water!9

Yesterday’s flowers are today but a dream.10

How sad my fate!

Upon my sorrow others heap their spite.

Now, drawn by the birch bow’s sound,

To find a moment of respite.

(sage-uta) Ah, how shameful that even now

I should shun the eyes of others

As on that festive day.11

(age-uta) Though all night long I gaze upon the moon,

Though all night long I gaze upon the moon,

I, a phantom form, remain unseen by it.

Hence, by the birch bow’s upper end,

I shall stand to tell of my sorrow,

I shall stand to tell of my sorrow. (As if listening, steps forward.)

(unnamed) From where does the sound of the birch bow come,

From where does the sound of the birch bow come?

TERUHI:

(ge-no-ei) Though by the mansion gate I stand,

ROKUJŌ:

As I have no form, people pass me by. (Steps back and weeps.)

TERUHI:

(unnamed) How strange! I see a gentle-born lady,

Though I know not who she is,

Riding in a decrepit cart,

And one who seems a waiting-maid,

Clutching the shaft of the ox-less cart

And weeping, bathed in tears.

Oh! pitiful sight! (Speaks to the Courtier.)

(mondō) Is this the evil spirit?

COURTIER:

Now I can guess who it is. Tell me your name.

(Not seeing Rokujō’s spirit, turns to Teruhi.)

ROKUJŌ:

(kudoki-guri) In this world

Where all passes like lightning,

There should be none for me to hate

Nor any fate for me to mourn;

Why did I leave the way of truth? (Speaks to Teruhi.)

(kudoki) Attracted by the birch bow’s sound,

Here I now appear. Do you still not know me?

I am the spirit of Lady Rokujō.

In days of old when I moved in society,

On spring mornings I was invited

To the flower feasts at the palace,

I viewed the moon in the royal garden.

Happily thus I spent my days

Among bright hues and scents.

Fallen in life, today I am no more

Than a morning glory that withers with the rising of the sun.12

My heart knows no respite from pain;

Bitter thoughts grow like fern shoots

Bursting forth in the field.

I have appeared here to take my revenge.

CHORUS:

(sage-uta) Do you not know that in this life

Charity is not for others?

(age-uta) Be harsh to another,

Be harsh to another,

And it will recoil upon you.13

Why do you cry?

(Rokujō gets up and, gazing at the kosode kimono and stooping down, weeps. She stares at it again.)

My curse is everlasting,

My curse is everlasting.

ROKUJŌ:

(mondō) Oh, how I hate you!

I will punish you.

TERUHI:

What shame!

For Lady Rokujō, gentle born,

To seek revenge14

And act as one lowborn:

Are you not ashamed?

Stop and say no more.

ROKUJŌ:

Say what you will, I must strike her now.

(Walks to the kosode and defiantly strikes it with the fan.)

So saying, I walk toward the bedside of Lady Aoi and strike her.

(Returns to her seat.)

Now that things have come to such a pass,

There is nothing more to do.

So saying, I walk toward Lady Aoi’s feet

And torment her.

ROKUJŌ:

Present vengeance is the retribution

For past wrongs you did to me.

TERUHI:

The flame of consuming anger

ROKUJŌ:

Scorches only my own self.15

TERUHI:

Do you not feel the fury of my anger?

ROKUJŌ:

You shall feel the fullness of its fury. (Fixes her gaze on the kosode.)

CHORUS:

(dan-uta) This loathsome heart!

This loathsome heart!

My unfathomable hatred

Causes Lady Aoi to wail in bitter agony.

But as long as she lives in this world,

Her bond with the Shining Genji will never end—

The Shining Genji, more beautiful than a firefly

That flits across the marshland.

ROKUJŌ:

I shall be to him

CHORUS:

A stranger, as I was once,

And I shall pass away

Like a dewdrop on a mugwort leaf.

When I think of this,

How bitter I feel!

Our love is already an old tale,

Never to be revived even in a dream.

Yet all the while my longing grows

Until I am ashamed to see my love-torn self.

Standing by her pillow,

I shall place Lady Aoi

In my wrecked cart

(Rokujō pulls the outer kimono over her and, stooping, withdraws to the stage-attendant position.)

And secretly carry her off,

And secretly carry her off.

Act 2

A Messenger of the minister of the left, wearing a striped kimono, sleeveless robe, and trailing divided skirt, is seated at the kyōgen seat.

COURTIER: (mondō) Is anyone here?

MESSENGER: I am at your service. (Comes forward in front of the Courtier.)

COURTIER: Lady Aoi, who is possessed by an evil spirit, is grievously ill. Go! Fetch the holy man of Yokawa.

MESSENGER (returns to the shite spot): (unnamed) I understood that Lady Aoi, though possessed by an evil spirit, was very much better. Now I am told that she is more ill than ever. Therefore I am ordered to go to Yokawa and bring the holy man back with me. I must make haste. (Goes to the first pine and, turning toward the curtain, calls out.) I have arrived. If you please, I wish to be announced.

The Holy Man, wearing a small round cap, brocade stole, heavy silk kimono, wide-sleeved robe, and wide white divided skirt and carrying a short sword and a rosary of diamond-shaped beads, appears and advances along the bridgeway, stopping at the third pine.

HOLY MAN:

(mondō) Before the window of the Nine Ideations,16

On the seat of the Ten Vehicles17

I am filled with the waters of yoga,18

Reflecting the Moon of Truth in the Three Mysteries.19

Who is it that seeks admission?

MESSENGER: I am a messenger from the minister. Lady Aoi, who is possessed by an evil spirit, is grievously ill, and I am commanded to ask you to come at once and perform an exorcism.

HOLY MAN: Of late I have been engaged in performing special rites and cannot leave, but since it is a request from the minister, I will go immediately. You may return at once.

MESSENGER: I will lead the way.

I have returned, my lord, accompanied by the holy man.

The Holy Man enters the stage and stands in the shite spot, where the Courtier turns to him.

COURTIER: I am much obliged to you for coming.

HOLY MAN: I received your message. Where is the lady who is ill?

COURTIER: She is there in the gallery. (Turns to the kosode.)

HOLY MAN: I shall perform the exorcism at once.

COURTIER: Pray do so.

To notto music, the Holy Man moves in front of the musicians, tucks up his sleeves, and advances toward the kosode.

HOLY MAN:

(unnamed) He now performs the healing rites,

Wearing his cloak of hemp,

In which, in the footsteps of En-no-Gyōja,20

He scaled the peaks21

Symbolic of the sacred spheres

Of Taizō and Kongō,22

Brushing away the dew that sparkles like the Seven Jewels,23

And with a robe of meek endurance24

To shield him from defilements,

Fingering his reddish wooden beads,

And rubbing them together, he intones a prayer: Namaku, samanda, basarada.

The spirit of Lady Rokujō, having exchanged the golden-painted-eyes mask for a hannya mask and covered her head with her brocade outer kimono, stands behind the Holy Man with a hammer-shaped staff in her hand and fixes her gaze on him.

(Quasi dance: inori)

The Holy Man turns toward Rokujō and tries to vanquish her by his incantation, but she wraps her brocade outer kimono around her waist and takes a defiant attitude. Then she kneels, supporting herself with her hammer-shaped staff.

ROKUJŌ:

(kakeai) Return at once, good monk, return at once.

Otherwise you will be burdened with regret.

HOLY MAN:

However evil the evil spirit,

The mystic power of a holy man will never fail.

With these words I once again finger my sacred rosary.

CHORUS:

(chū-noriji) Gōzanze Myōō, Wisdom Kings of the East,

ROKUJŌ:

Gundari-yasha Myōō of the South,

CHORUS:

Daiitoku Myōō of the West,

ROKUJŌ:

Kongō-yasha Myōō

CHORUS:

Of the North,

ROKUJŌ:

The most Wise Fudō Myōō of the Center—25

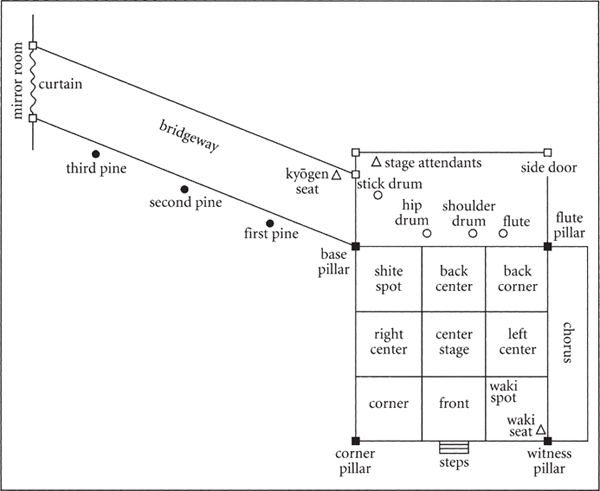

In act 2, the prayers of the Holy Man of Yokawa prevent Lady Rokujō’s spirit, wearing a hannya mask, from harming Aoi (represented by a folded kimono). (From Meiji-Period Nō Illustrations by Tsukioka Kōgyo, in the Hōsei University Kōzan Bunko Collection)

Namaku samanda basarada senda makaroshana sowatayauntara takamman!26

Whoever hears my teaching

Shall gain profound wisdom;

Whoever knows my mind

Shall gain the purity of buddhahood.27

Rokujō, subdued, drops her staff and covers her ears.

(unnamed) How fearful is the chanting of the sutra!

My end at last has come.

Never again will this evil spirit come.

CHORUS:

(kiri) Hearing the voice of incantation,

Hearing the voice of incantation,

The demon’s heart grows gentle. (Rokujō rises, as if rid of her curse.)

Forbearance and mercy incarnate,

The Bodhisattva comes to meet her.

She enters nirvana,

Released from the cycle of death and rebirth—Buddha be praised!

Released from the cycle of death and rebirth—Buddha be praised!

Rokujō goes to the shite spot, joins her hands in prayer, and stamps twice.

[Adapted from a translation by Gakujutsu shinkōkai]

STUPA KOMACHI (SOTOBA KOMACHI)

Attributed to Kan’ami and revised by Zeami

The image of Ono no Komachi as a flawlessly beautiful poet has prevailed for more than a thousand years. The Kana Preface to the Kokinshū (ca. 905) praises her as a successor to Sotoori-hime, a legendary princess of peerless beauty who was regarded as the goddess of poetry. But aside from Komachi’s excellent poems, which are the source of the diverse legends about her, nothing certain is known about her life. From those poems in which she laments her lost beauty and youth, the legend arose that late in her life she became exceedingly ugly and haggard. The poems describing her unrequited passion gave rise to her image as an amorous woman (in the medieval period, she was sometimes even depicted as a courtesan), while in other pieces she scolds and rejects her suitors, suggesting the opposite image, that of a coldhearted beauty. The image of Komachi as a belle dame sans merci took shape in the legend of Fukakusa no Shōshō’s visits of a hundred nights, in which Komachi is said to have once promised to reciprocate this courtier’s love on the condition that he appear outside her home for a hundred nights in succession. As the legend goes, however, he died on the ninety-ninth night, the eve of the fulfillment of his quest.

Subsequently, in the medieval period, the Buddhist exemplum The Flowering and Decline of Tamatsukuri Komachi (Tamatsukuri Komachi sōsuisho) came to be regarded as the definitive historical document of the poet’s life. Written around the year 1000, most likely by a Buddhist preacher, this story relates a monk’s encounter with an ugly old beggar, who, it turns out, was born into a wealthy family. She explains to the monk how she once boasted of her beauty and cruelly rejected her suitors but then lost her youth and family fortune, ending up as a beggar. Scholars disagree as to whether this story originated independently of the legend of Ono no Komachi. In any case, Tamatsukuri contributed to the enduring image of Komachi as a decrepit, hundred-year-old beggar.

These legends are evident in Stupa Komachi, which draws heavily on Tamatsukuri and the tale of Shōshō’s hundred nightly visits. The play opens with an encounter between two traveling monks and the wandering beggar Komachi. (Unlike in Tamatsukuri, in the play Komachi roundly refutes the monks’ shallow preaching.) The play also borrows or paraphrases many passages from Tamatsukuri contrasting the tattered clothes and miserable life of the aging Komachi with her past glory and beauty. In the latter part of the play, Komachi is suddenly possessed by the spirit of the dead Shōshō (Lesser Captain), who makes her reenact in front of the monks his hundred nights of visits to her, as if to bring home to her how cruel her treatment of him was.

The play was originally written by Kan’ami and then revised by his son Zeami. Since the original by Kan’ami is now lost, the extent of Zeami’s contribution is not certain, except for his brief comment in Conversations on Sarugaku (Sarugaku dangi) that the original was much longer and included a scene in which a messenger of Tamatsushima—a god of poetry—appears in the form of a bird.

Such ambiguity in authorship is a problem common to early nō plays, almost none of which remained untouched by Zeami. It is not that Zeami was unusually fond of revising others’ plays; rather, adapting old plays was a common practice among nō playwrights, including Kan’ami. The concept of authorship was not as strict at that time as it is now, and it was necessary to continually revise plays for new troupes and for audiences’ changing tastes. It was only after Zeami had established the basic aesthetic principles and structure of nō plays that the practice of revising the plays subsided.

Although Zeami revised all the extant plays by Kan’ami, they still retain characteristics of Kan’ami’s style, such as the vivid and witty conversation and the realistic representation of dramatic story lines, which often include confrontations between characters. These characteristics, which can clearly be seen in Stupa Komachi, are in fact the remnants of sarugaku from Yamato Province. Later, Zeami attenuated these features through his reformation of no, bringing it more in line with the principle of yūgen.

The play’s antiquity is indicated also by Shōshō’s possession of Komachi. In Teachings on Style and the Flower (Fūshikaden), Zeami classifies “derangement” (monogurui) into two types, one due to possession by a spirit or god and the other to an emotional crisis, usually precipitated by the loss of a lover or child. For female protagonists, Zeami recommends the latter type of derangement but rejects the former. He in fact wrote numerous nō plays that feature a distraught female protagonist seeking her lost child or lover, which became the standard for later generations of playwrights. Before Zeami, however, presumably many plays dealt with female characters whose derangement was caused by possession, but most were gradually omitted from the repertoire and eventually disappeared altogether. Stupa Komachi is a rare exception. With such diverse scenes, presented one after the other—the fiery and witty debate between the monks and Komachi, her bemoaning her lost beauty and current misery, her possession by Shōshō’s spirit, and her reenactment of his one hundred nightly visits—the play remains one of the most popular in today’s repertoire, even though only a few performers, of mature years and superior skill, are permitted to play this highly prized and prestigious role.

Characters in Order of Appearance

MONK | waki |

COMPANION, also a monk | waki-tsure |

ONO NO KOMACHI, a poet, now a very old woman (uba mask) | shite |

To shidai music, enter slowly Monk with Companion. They stand side by side at the front of the stage and then face each other.

MONK AND COMPANION:

(shidai) Mountains are but shallow hideaways;

mountains are but shallow hideaways; what hermitage

is deeper than the heart?

Monk faces forward.

MONK: (nanori) I am a monk come from the monasteries of Mount Kōya. I thought I’d pay a visit to the capital, and am on my way there now.

(sashi) The Buddha that once was has now passed on; the Buddha that shall be is not yet come into the world.28

Monk and Companion face each other again.

MONK AND COMPANION:

Born into such a dreamlike in-between,

what can we take for real?

By chance we have obtained this human body,

so difficult to obtain,

and have encountered the teachings of the Buddha,

That this is the seed of enlightenment we know,

as tokened by these robes as black as ink

in which we drape ourselves.29

(age-uta) Knowing our self-nature before birth,

Knowing our self-nature before birth,

we have no parents who can claim our love.

We have no parents; and we have

no children to constrain their hearts

with worry for our sakes. (Monk mimes walking.)

This self that goes a thousand leagues

and does not count it far,

bedding down in meadows,

dwelling in the mountains:

this is our true home,

this is our true home.

MONK: (tsuki-zerifu) Having hastened along, already we have come, it seems, to the pine forest of Abeno, in the province of Settsu. Let us rest here for a bit.30

COMPANION: Yes, by all means.

Monk and Companion sit in the waki spot.

Stage assistant brings out a stool from backstage and places it center stage. It represents a decaying stupa. To narai no shidai music, Ono no Komachi enters, moving very slowly with the aid of a walking stick and pausing to rest as she moves down the bridgeway. Stopping at the shite spot, she stands facing the rear.

KOMACHI:

(shidai) Were there but a stream to woo this floating water plant,

were there but a stream to woo this floating water plant …

But there is none—only a lonely, aching heart.31 (Faces forward.)

(sashi) Ah, but oh so long ago

I was the proudest of them all,

my raven tresses sensually rippling

like weeping-willow streamers

wafted lightly on spring breezes.

And the trilling of this warbler

was more exquisite even than

the dew-drenched itohagi blossoms,

their petals only just begun to fall.

But now, despised even by lowly common wenches,

my shame exposed for one and all to see,

as joyless days and months heap up upon me,

I have become a hundred-year-old hag.

(sage-uta) In the capital I hide myself from people’s gaze;

“Can that be she?” they murmur, faint

light of the gloaming in which,

(age-uta) with the moon for company, I venture forth,

with the moon for company, I venture forth.

The men who guard the palace—

that grand abode among the clouds, built from myriad stones

upon the heights—

will surely pay no heed to such a wretch as I;

why then, there is no need for slinking, hidden

in the shadows of the trees

of the Tomb of Love32

at Toba, and the Autumn Hill,

and moonlit Katsura riverboat—(Facing stage right, peers into the distance from under her wide sedge hat.)

rowing it away, who can that be?

rowing it away, who can that be? (Plants her walking stick before her, right hand atop the stick, left hand atop the right, and gazes into the distance.)

(tsuki-zerifu) I am in such pain—(Looks over at the stool.) I think I’ll just sit down and rest upon this moldering piece of wood.

Removes her sedge hat and, holding it in her hand, slowly makes her way to the stool and sits down on it. Monk and Companion stand up.

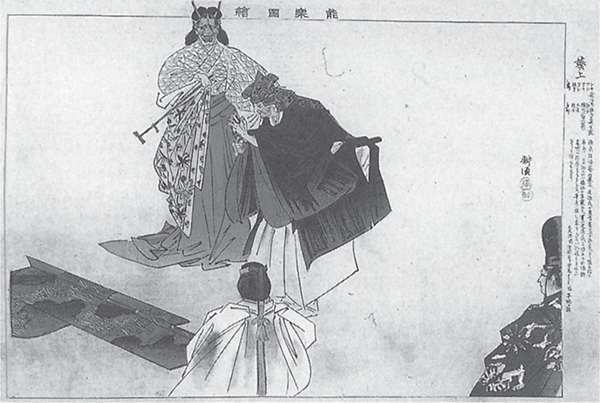

Komachi, holding a walking stick and a wide sedge hat, sits on a stupa and rebuts a sermon by two monks. (From Meiji-Period Nō Illustrations by Tsukioka Kōgyo, in the Hōsei University Kōzan Bunko Collection)

MONK: (mondō) Why, already the sun has set. We must hasten on our way. But look! that beggar there: surely that is a stupa she is sitting on.33 Let us teach her the error of her ways and have her move away from it.

COMPANION: Yes, by all means.

Companion passes behind Komachi and moves toward the corner pillar so that the three characters form a triangle, with Komachi at its apex and Monk and Companion forming its base.

MONK: (mondō) How now, you beggar, there! That place where you are sitting—do you not know that you are profaning a stupa, the form of Buddha’s body? Get up from there; go rest some other place!

KOMACHI (to Monk): Profane—the form of Buddha’s body, you say! But I see no writing here, no carven image; it looks like just a moldering piece of wood to me.

(kakeai) Though but a moldering piece of wood

in mountains deep,

when the tree has blossomed

there’s no hiding what it is.

And all the more so when the wood’s carved in the form of Buddha’s body—how can you say there was no indication?

Komachi remains seated during the ensuing exchange as she responds to Monk and Companion, speaking slowly throughout, with pretended ignorance.

KOMACHI:

I am myself a lowly, buried tree,

yet still the blossom of my heart remains;

why, then, should this not be my offering?34

But tell me: why is this to be viewed as Buddha’s body?

COMPANION:

You see, a stupa is how Vajrasattva,

provisionally manifesting in the world,

embodied the Buddha’s sacred vow

in symbolic form: as a samaya body.35

KOMACHI:

This form it is embodied in: what is it?

MONK:

Earth, water, fire, wind, and space.

KOMACHI:

Those Five Great Elements’ five rings

make up the body of a person—so between us

why should there be any separation?36

It may not be dissimilar in form,

but in mind and merit it is clearly different.37

KOMACHI:

And what, pray, is a stupa’s merit?

MONK:

One glimpse of a stupa frees you forever

from rebirth in the three lower realms.38

KOMACHI:

The essence of enlightened mind

that flashes in one instant:

now how is that inferior?39

COMPANION:

But if you claim enlightened mind,

why have you not renounced this world of suffering?40

KOMACHI (unaffectedly and clearly):

You think it is the outward form

that renounces the world?

It is the mind that renounces.

MONK:

Yours is a body with no mind;

no doubt that’s why

you do not know the body of the Buddha.

KOMACHI: Indeed, it is because I know this as the Buddha’s body that I come near to a stupa.

COMPANION:

In that case why did you sit down on it

without so much as bowing?

Komachi looks at the stupa.

KOMACHI (with growing force):

In any case this stupa is reclining;

can it object that I too should relax?

That is a far from proper connection

to the Buddha.

KOMACHI:

Even a backward connection can lead to enlightenment.41

COMPANION:

Even Daiba’s evil

KOMACHI:

is Kannon’s compassion.42

MONK:

Even Handoku’s stupidity

KOMACHI:

is Monju’s wisdom.43

COMPANION:

Even what we call evil

KOMACHI:

is good.

MONK:

Even what we call the passions

KOMACHI:

is enlightenment.44

Enlightenment, at its root,

KOMACHI:

is not a tree.

MONK:

And the clear mirror—

KOMACHI:

—mind’s mirror-on-a-stand—there’s no such thing. (Decisively turns to face forward.)

CHORUS:

(uta) Indeed, when in the first place not one thing exists,

there is no separation between

buddhas and sentient beings.45 (Companion moves back next to Monk and sits down.)

(age-uta) To this, the Buddha’s

solemnly sworn vow of compassion,46

this expedient devised

for saving ignorant, deluded beings,

even a backward connection

can lead to enlightenment. (She turns earnestly toward Monk.)

—Thus she explains,

at which the monk cries,

Truly, an enlightened mendicant! (As though unable to help himself, Monk falls back two or three steps, sinks to his knees, and deferentially lowers his forehead to the earth.)

and lowering his forehead to the earth,

three times he makes obeisance,

whereupon:

KOMACHI:

I now feel stronger, so I shall make bold

to compose a frivolous verse:

(ge-no-ei) (easily, in a low voice) If we were in the heaven of Supreme Bliss:

but here outside,

whatever can you be objecting to?47

Abruptly rising, she turns her back to Monk as though in annoyance and moves away several steps toward the base pillar.

CHORUS:

(uta) Presumptuous priest, who would

“teach me the error of my ways”!

Presumptuous priest, who would

“teach me the error of my ways”!

MONK: (unnamed) (to Komachi’s back) But what manner of person are you? Please tell us your name!

Komachi turns to face Monk.

KOMACHI: Embarrassing though it is, I shall tell you my name. (Moves slowly to center stage and sits facing forward.)

(nanori-guri) (haughtily, yet sadly) I am what has become of

Ono no Komachi,

daughter of Ono no Yoshizane,

governor of Dewa Province.

MONK AND COMPANION:

(sashi) My heart goes out to her.

Komachi—ah, truly, long ago

she was a lady of surpassing beauty:

her visage like a flower, radiant,

her eyebrows two slim blue crescents,

her face invariably powdered white,

she had so many fine silk robes,

they overflowed her mansion.

KOMACHI:

Thus I remained absorbed in my appearance,

CHORUS:

and men far away ached for me,

while men close by were plunged in utter gloom;

KOMACHI:

and I, in robes whose turquoise breakers foamed

upon a cobalt coast,

like sunset-painted clouds ringed round with cobalt peaks,

KOMACHI:

resplendent

CHORUS:

as a floating lotus blossom

lapped by daybreak waves,48

KOMACHI (slowly):

Composing Japanese poems

and writing Chinese verse, …

CHORUS:

When she raised a cup of heady wine,

the stars and moon would tarry on her sleeves.

That peerless grace and beauty—

when was it so utterly transformed?

(age-uta) Her head’s crowned with a frosted, drooping thatch,

and at her temples those once-lovely, flowing locks

cling limply to her skin in random streaks;

her gently curving brows, twin butterflies,

have lost their hue that was like distant hills.

(sage-uta) A year short of a hundred—ninety-nine—

oh, that the grief of these white, straggly locks

should have come to her one day!49—

wan daylight moon: (Komachi hides her face with her hat.)

how mortifying her appearance now! (She rises and moves toward the shite spot.)

(rongi) The pouch that you have hung around your neck—

what do you have in it?

KOMACHI:

Although I know not whether life may end today,

to save me from hunger tomorrow I’ve brought along

some dried millet-and-beans inside this bag.

CHORUS:

And in the bag you carry on your back?

A garment soiled with dirt and grease.

CHORUS:

And in the basket in the crook of your arm?

KOMACHI:

Kuwai roots, both black and white.50

CHORUS:

With tattered cloak of straw

KOMACHI:

and tattered hat of sedge, (Looks at the hat in her hand.)

CHORUS:

you cannot so much as hide your face, (She looks down, betraying some emotion.)

KOMACHI:

much less keep out the frost, snow, rain, dew,

CHORUS:

tears—even her tears

she has not cuffs and sleeves enough to staunch! (Examines first one sleeve and then the other.)

And now she wanders by the roadside, (With both hands, Komachi thrusts out her hat, turned upside down, and moves purposefully toward the corner pillar.)

begging from passersby.

When she cannot beg what she needs, (Komachi peers searchingly into her hat.)

an evil mood, (With a deranged air, takes two or three steps.)

a crazy wildness, takes her mind,

and her voice grows weirdly altered. (Abruptly throws down her walking stick.)

KOMACHI (again thrusting out her hat with both hands, and advancing toward Monk):

(mondō) I pray you, sir, vouchsafe me something.

I beg of you, reverend monk, I beg of you. (Presses toward Monk, to around center stage.)

MONK: What is it you want?

KOMACHI: Let us go calling on Komachi—oh yes, please!

MONK: But you yourself are Komachi! Why do you speak such nonsense?

KOMACHI (facing forward): Ah, but that Komachi, what exquisite charms were hers! (Looking this way and that.) Love letters from here, missives from there, (Backing away slightly.)

written by love-beclouded hearts,

poured down upon her

like the summer rains

darkening the heavens.

Yet she would not answer even once,

not even in words empty as the sky. (Turns her face downward, evidently holding back strong emotion.)

Now she is one hundred years of age—

her karmic retribution.

Ah, how I long for her!

Ah, how I long for her!

MONK: “I long for her,” you say? What manner of being is it, then, possesses you?

KOMACHI (turning toward Monk):

Of all the many men who staked their hearts on Komachi, (Faces decisively forward.)

the deepest love was that of Shii no Shōshō,

of Fukakusa’s deep grasses;

CHORUS:

(uta) for Shii no Shōshō

the tally of love’s grievances

rolls round again; (Advances slightly, then stops, caught in the throes of attachment.)

to her carriage-shaft bench

I must go courting!51 (She looks off to the west, toward the bridgeway.)

(age-uta) What time of day is it?—twilight.

With the moon as my companion,

I shall set out on the road to her.

Though there be barrier guards to block the way,52

I will not let that stop me; off I go. (Goes to the stage-assistant position and turns her back to the audience.)

(Costume change)

While monogi-ashirai music is played, the actor playing Komachi lengthens his sleeves by lowering the shoulders of his outer robe; or he may exchange it for a chōken (man’s overrobe). He then dons an eboshi (black-lacquered court hat), takes up a fan, and proceeds to the shite spot.

KOMACHI (looking down at her trouser hems and stamping once):

(uta) Hitching up the legs of my white trousers,53

(Quasi dance: iroe)

To musical accompaniment, she moves very slowly to the corner pillar, then circles left to back center and stops, facing forward. Although her movements have no meaning in themselves, the romantic ardor of the Shōshō as he makes his way to Komachi is perceptible. She continues dancing and miming as the text resumes.

KOMACHI:

Hitching up the legs of my white trousers,

folding down my tall court hat, (Raises fan and points with it to her head.)

and draping my robe’s sleeve over my head,54 (Flips left sleeve over her head and half-hides her face with fan.)

I make my way to her in stealth, avoiding the world’s gaze,

going in bright moonlight or in darkness, (Lowers her hands and faces forward, gazing up into the sky.)

on rainy nights and windy nights,

when chilly autumn leaves come drizzling down,

and when the snow lies deep.

(unnamed) As from the eaves the jewel drops melt and patter

quick-quick-quick-quick (Looks upward and around.)

CHORUS:

(uta) go and then return, (Komachi moves away two or three steps.)

return, then go again: (Bends the fingers of her left hand, counting.)

one night, two nights, three nights, four,

seven nights, eight nights, nine nights—

to attend the harvest feast, the Light of Plenty,

I did not appear at court,

and yet neither did she appear to me—

at cockcrow, timely as the rooster with each dawn,

I inscribed the nightly count

upon the edge of her shaft bench.

I’d sworn to go to her a hundred nights; (Stamps several times.)

so came the ninety-ninth night. (Extends her left hand and looks at her still unbent little finger.)

Oh, agony! The world grows dark before my eyes…. (Falls back to center stage, pressing her fan to her breast as though in pain.)

A pain within my breast, he cried in sorrow, and,

not tarrying that one last night, so died (Drops to one knee, then sits.)

the Shōshō, of Fukakusa’s deep grasses, he

whose bitter indignation (Sits bolt upright, then rises.)

takes possession of Komachi, (Earnestly facing Monk, stamps her foot.)

visiting on her this state of frenzy.

Komachi’s attitude now shifts, and she becomes completely tranquil.

(kiri) And thus we see that aspiration for the life to come

is the true way. (Slowly extends fan, as though beckoning from afar.)

Piling up sand to make a stupa tower,55

burnishing the Buddha’s golden skin

with loving care,

offering up a flower, (Slowly closes fan, joins her hands as if in prayer.)

let us enter the path of awakening,

let us enter the path of awakening.

[Translated by Herschel Miller]

Attributed to Zeami

The play’s title, Matsukaze, is taken from the name of its protagonist, the ghost of a female saltmaker. Matsukaze means “wind (kaze) in the pines (matsu)” as well as “the wind (kaze) that awaits (matsu).” Poetic puns on this homonym recur throughout the play. The protagonist is the ghost of a rural girl, lingering on the desolate seashore of Suma—like a lonely wind blowing through the coastal pines—awaiting the return of her lover, who long ago set off for the capital and never returned.

The play’s authorship has long been the subject of scholarly debate, but it is now generally accepted that it was probably written by Zeami, although he seems to have borrowed several chanting sections from earlier compositions.56 The precise relationship between the play and its original source also remains obscure. The image of two saltmakers drawing seawater under the moon was probably taken from Drawing of Seawater (Shiokumi), a play now lost. Pining Wind’s central plot—an affair between Ariwara Yukihira (818–893), a noble exiled from the capital, and two sisters from Suma Bay, his place of exile—cannot be found anywhere else and was probably Zeami’s own invention. Yukihira, a grandson of Emperor Heizei, was exiled to Suma for some unknown reason. One account of his life in exile, in an anthology of Buddhist anecdotes (setsuwa) entitled Senjūshō, recounts an episode in which Yukihira exchanged words with a local fisherperson (ama).57 Although this account offers no hint of any love affair, certain romantic connotations are associated with fisherwomen in literature and legends, some of which depict a girl by the sea marrying a noble aristocrat and bearing his child.

The “Suma” chapter of The Tale of Genji links the image of Yukihira in Suma—a nobleman lamenting his exile to a desolate seashore—to the romantic portrayal of fisherwomen. Like Yukihira, Genji, in self-imposed exile, spends a period of time in Suma, after which he moves on to Akashi, a nearby coastal province. While there, he becomes involved with the Akashi lady, who likens her own status to that of rural girls working by the seashore. This lady, however, bears Genji his only daughter, a child who later becomes the mother of a crown prince, cementing Genji’s political power and worldly glory. Pining Wind borrows from Genji this relationship between a noble exile and a local girl at the seacoast and re-creates it as a story about Yukihira, who stays in Suma for three years, has an affair with two local girls, and leaves behind his robe and court cap as keepsakes before making the journey back to the capital, just as Genji left his robe with Lady Akashi before his own return to the capital. The play is replete with citations from Genji, especially in its description of the Suma seashore.