Before moving on to a detailed analysis of Nosferatu, I would like to clarify that for the purposes of this book, all references and quotations of dialogue (both in German and English) will refer to the two DVD editions of the film released respectively by the British Film Institute in 2002 and by Eureka/Masters of Cinema in 2007. Although there are other versions of the film available on the market that tend to vary quite a lot in terms of quality and respect to the original film, these two releases present a number of important features that are worth mentioning here, such as the restoration of the original tints and colours, and the re-implementation of Albin Grau’s intertitles. For what concerns the music in the case of the BFI, the film is accompanied by a newly composed soundtrack, whilst the Eureka edition features the first recorded rendition of the original score by Hans Erdmann.

The BFI version was restored in 1997 by the Münchner Filmmuseum and by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna, whereas the version released by Eureka Film was restored by Luciano Berriatúa on behalf of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in 2005/2006. More specifically, this edition employed a tinted nitrate print with French intertitles dated 1922 and preserved at the Cinémathèque Française as the basis for the restoration. The final product is the result of a long and complex work of investigation and reconstruction: some missing shots were retrieved using a 1939 safety print of the film preserved at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin/Koblenz, that was drawn from a Czech export print dating back to the 1920s. Other missing parts were instead taken from a nitrate print of 1930 that had been distributed under the title of Die zwölfte Stunde [The Twelfth Hour] and that was preserved at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris. Equally, the restoration and subsequent re-implementation of the original intertitles were based on another safety print dated 1962 and preserved in Berlin’s Bunderarchiv/ Filmarchiv that had as its basis a film’s print made in 1922. The missing intertitles were redesigned before insertion and can be recognised in the Eureka print because they are marked ‘FWMS’ (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung) at the bottom left corner of the screen.

Both versions replicate the tones and tints revealed by the surviving nitrate copy of the film thus giving the viewers the chance to truly appreciate the various narrative phases and nuances in the story that get inevitably lost in those purely black and white versions of the film where even Nosferatu’s final demise through the first ray of the morning sun does not make any real visual narrative sense. In silent cinema, tints and colours were determined by a set of clear colour-codes; thus for instance, night scenes that have no other visible source of light apart from the moon are tinted in blue whilst interior sequences set during the day are tinted in an amber shade.

These two versions also utilise the original intertitles characterised by the lettering designed by the film’s producer and set designer Albin Grau that recall closely the film’s original script by Henrik Galeen.

The BFI edition also features a new orchestral score composed by James Bernard (1925–2001) that, through the combination and juxtaposition of several contrasting musical themes, reconnects the soundtrack to the idea of the film as a ‘symphony’ where visual and narrative elements combine with socio-political issues which were relevant to Germany in the 1920s such as anti-Semitism, racism, pan-Germanism, fear of homosexuality and the collapse of moral and social values. More specifically, James Bernard, who also composed the music for a number of Hammer films such as Terence Fisher’s Horror of Dracula (1958), employs a series of very recognisable themes that although generally based on the bipolarity between Good and Evil, identified here by corresponding concordant and discordant sounds, accompany the various characters throughout the film. Therefore the three main characters are assigned their own musical theme, or to use the correct musical term – a leitmotif which the viewer can immediately recognise. Orlok’s theme is based on the syllables No-sfe-ra-tu expressed as a four-note motif (along the lines of Bernard’s work on the Dracula theme which was based on the Count’s three-syllables name – Dra-cu-la) that is played by low heavy brass (four trumpets, four trombones and a tuba). The musical theme of the film’s heroine Ellen, played by a large string section, conveys a sense of melancholy and romanticism but it is at the same time, intertwined with a secondary motif that subtly stresses the uncanny psychological link that runs between Ellen and the Count and that is established, as we will see, a number of times by Murnau by an artful use of editing and cross-cutting. Finally, Hutter’s theme is the combination of two distinct motifs that are representative of the character’s narrative evolution – although this evolution is never really accompanied by an equally profound development in the character’s understanding of the plague or of his own wife’s internal turmoil and intentions. The first theme, bouncy and lively, is played by woodwind instruments and is reminiscent of a rustic folk tune. It exemplifies Hutter’s naivety and almost adolescent enthusiasm in undertaking his journey to the mysterious ‘land of ghosts’ where Orlok is waiting for him. This theme is almost imperceptibly replaced by a second, more obscure motif that Bernard based on the lower line of Nosferatu’s own melodic tune. Hutter’s and Nosferatu’s life become inextricably linked as soon as Hutter crosses the castle’s archway entrance and thus the same must happen to the themes identifying the two characters. Finally, the theme connected to the shady character of Knock, based on strings and percussion, is particularly effective during the chase scene towards the climax of the film when the inhabitants of Wisborg pursue Orlok’s servant around the town and in the fields. The frantic and relentlessly fast pace of this sequence conveys in a very dramatic manner the desperation of the people battered by the mysterious plague that is decimating the town’s inhabitants and their almost animalistic instinct towards revenge. Often combining melodic lines pertaining to different characters in one multi-layered theme, James Bernard’s score manages to reproduce on an aural level the idea of the film as a symphony of converging narrative and thematic concerns.

The soundtrack on the Eureka edition is noteworthy because it features the original score composed for Nosferatu by the conductor, composer and music critic Hans Erdmann (1882–1942) in the reconstruction made by Berndt Heller. Erdmann gave his work the title Fantastisch-Romantische Suite which he divided into ten parts and was arranged in versions for both full and palm court orchestra (a term that indicates a smaller ensemble). Compared to the score by James Bernard, which follows the musical style of many of the Hammer film soundtracks, the original score by Erdmann is very much of its time, recalling the late German and Austrian romantic style. Composers such as Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and Alexander Zemlinsky particularly come to mind. Again, leitmotif is used but what this score really achieves very successfully is the expression of a wide range of emotion and characterisation. Other music is also included in the score: works by Bizet, Becce, Verdi, Boito and Percy E. Fletcher. The music for the closing sequence uses an orchestration of Chopin’s Nocturne in G minor, Op. 15/3.

In his book

The Philosophy of Horror (1990), Noel Carroll identifies a generic narrative template structured around four phases that although often subjected to variations, could be employed as a blueprint in the reading and analysis of horror films. This template, which he denominates the ‘complex discovery plot’, is usually composed of an

onset, a

discovery, a

confirmation, and a

confrontation stage. As anticipated by Roy Ashbury in his brief study of Murnau’s film, these phases and their inevitable diversions from the basic model could be superimposed on

Nosferatu and used to conduct an in-depth reading of the film’s narrative developments.

37THE ONSET PHASE

In the onset phase the audience is made aware for the first time of the monster’s presence. In Noel Carroll’s words:

We know a monster is abroad and about. The onset of the monster begins the horror tale proper, though, of course, the onset of the monster may be preceded in the narrative by some establishing scenes that introduce us to the human characters and their locales […]

38

The beginning of the film is heralded by a series of three intertitles establishing the time and the place of the action:

Chronicle of the Great Death in Wisborg. Anno Domini 1838 by

__________________

Nosferatu

Does this word not sound to you like the midnight call of the Deathbird. Take care in saying it, lest life’s images fade into shadows, and ghostly dreams rise from your heart and nourish themselves on your blood.

__________________

Long have I contemplated the origin and recession of the Great Death in my hometown of Wisborg. Here is its story: There lived in Wisborg Hutter and his young wife Ellen.

These three intertitles are just the first example of the wealth of documents, such as diary entries, letters, newspaper clippings etc. that replicate in Murnau’s film the multiple-voice narrative employed by Bram Stoker in his novel. The story, a ‘chronicle’, is immediately identified as the account of real events. We do not know who the unnamed narrator of the story is (although in some French prints of the film – and with a radical diversion from the original script – he is identified as Johann Cavallius/ Carvallius, historian of the city of Bremen). What we do know though is that he has received a first-hand account of the events by Hutter himself, as he declares in a subsequent intertitle that we shall discuss later. The three intertitles are also notable because their layout immediately highlights, even on a purely visual level, the key elements in the story. Wisborg, the shadow of death symbolised by the three ominous crosses used as signature, the Great Plague, Nosferatu and its link with night and blood, Hutter and Ellen are all mentioned in the space of the film’s first few minutes. The onset could hardly be much clearer than this: the spectators are immediately plunged into a story populated by ‘shadows and ghostly dreams’.

The first image of the film is an establishing shot that Murnau filmed from the 80m tower of the now destroyed Marienkirche (St Mary’s Church) in Wismar. This panoramic shot presents to the viewer a quiet, orderly town with a few people moving about, but the sense of peace is only a fleeting impression for, through the intertitles, we have already been alerted that this situation is destined to change soon and in a dramatic way. The establishing shot is concluded by an iris in and out that introduces us to a scene of marital life between Hutter and Ellen. The first image of Hutter is a medium close-up with the character’s back to the camera; his face is reflected in a tiny mirror that barely contains his features, while he is adjusting his tie. Through this shot Murnau immediately plants a couple of subtle but unmistakable hints to Hutter’s personality into the spectator’s mind: vanity and a lack of perspective seem to be two of its defining traits. Hutter smiles at his reflection and then turns, still grinning, towards the left of the frame. With a quick movement, another clue to his lively but ultimately puerile personality, he turns to the right of the frame and approaches the window in the background of the shot. We now see Ellen surrounded by flowers and playing with a kitten. The mise-en-scène of this short sequence presents her character as someone consistently different from her husband: she quite clearly entertains a strong connection with nature and the contrast between Hutter’s cramped mirror and Ellen’s window suggests that she is not afraid of looking beyond her immediate horizon. The follow-up of the sequence will give us a further idea about the characters’ personalities and the level of interaction and intimacy between them. We cut back to Hutter who runs out of the room towards the right of the screen. Through another iris in and out, Murnau cuts to the garden where Hutter is collecting flowers to make a posy for his wife. While Ellen is busy embroidering, we notice Hutter peaking through the door to observe her. A quick intercut shows us the two characters facing each other, their demeanour completely different: Ellen seems happy but somewhat restrained while facing her husband from across the room, whilst Hutter has the attitude of a mischievous child as he approaches her – ‘he laughs and laughs’ scribbled Murnau on his copy of the script – hiding the flowers behind his back. When he finally presents her with the posy, Ellen’s reaction challenges our expectations: instead of showing appreciation for her husband’s romantic gesture, she nurses the flowers with a saddened expression. The intertitle – ‘Warum hast Du sie getötet…die schönen Blumen…?!’ (‘Why did you kill them…the lovely flowers…?!’) – not only reiterates her deep tie with nature but also offers to the viewer a new interpretative glimpse into her personality that appears to be melancholic and finely in tune with the idea of mortality. Also the choice of words in the intertitle, ‘kill’ instead of the more obvious ‘pick’, seems to reinforce this interpretation: whilst Ellen contemplates nature, Hutter is ready to destroy it and the whole exchange can be read as a premonition of the violence against nature and human, living things that will be brought on by the vampire’s arrival in Wisborg. The image following the intertitle is a medium shot of Hutter hugging Ellen to console her, although it is clear from his bemused and condescending expression that he does not really understand his wife’s distress, and their body language, just like in the previous short sequence where they embrace and kiss, suggests fraternal affection rather than erotic intimacy. Overall, we leave this sequence behind with a sense of saccharine formality and falseness.

In the following long shot, we see Hutter walking towards the camera on his way to work. A chance encounter with Professor Bulwer offers to the viewer another hint of the danger awaiting him. Out of the blue and for no apparent reason, the Professor warns Hutter that ‘[…] no one can escape his destiny’ and there is no need to be so hasty. This short interlude works as an introduction to the following section of the onset phase where the extent of the danger lurking over Hutter starts taking a darker and more concrete shape. The sequence is introduced by a new intertitle:

There was also an estate agent called Knock, about whom there were all manner of rumours. One thing was certain: he paid his people well.

Knock’s office is presented to the viewer with a series of typical Expressionist traits: it looks cramped, occupied by shelves and littered with piles of papers and documents. The lines of the walls are slanted thus suggesting a sense of oppression and danger. Knock himself is a bizarrely grotesque figure: dressed in an ill-fitting suit, with dishevelled hair and an unhinged look in his eyes, he is perched on a high stool like a monkey on the branch of a tree.

He is unmistakably human but there is also something disturbingly untamed and deranged about his appearance and demeanour that reinforces the connection between him and the feral nature of the Nosferatu himself. In the film’s original typescript Knock is thus described:

Knock’s spindly hunch-backed figure. Grey hair, weather-beaten face full of wrinkles. Around his mouth throbs the ugly tic of the epileptic. In his eyes burns a sombre fire.

39

Another clue to the relationship between Orlok and Knock is represented by the letter covered in a series of mysterious and arcane symbols that we see him reading in a slightly prolonged medium shot. As already mentioned, the strange language used in the letter was put together for the film by Albin Grau and it is the result of the film producer’s keen interest in the occult sciences. In volume number 228 of the French magazine Positif (1980), Sylvain Exertier conducted an intriguing breakdown of the letter and – although the document has not been entirely deciphered yet – he recognised and explained an ample selection of the symbols and drawings used in the message. The letter should be read from left to right and is marked by what Exertier called a ‘relative legibility’, a rather striking fact considering that esoteric texts are normally written following the model of grimoires – books of spells and magic – that would not be readable without the help of a key that is usually only owned by the ritual’s master and his disciples. The symbol opening the letter – a Kabbalistic square enclosed in a circle representing chaos – should function as a key providing the details for the performing of the ritual. The first line of the letter, instead, can be read as a sort of title and it is enclosed in between two Maltese crosses, the symbol of the crusading order of the Knights Hospitalier, that seem to suggest that Count Orlok is indeed about to embark on his own personal crusade. There are many other fascinating symbols used in the letter, such as traditional swastikas representing perseverance and a dragon’s head placed before a wavy line suggesting how death will bring destruction coming from across the sea. Exertier and other scholars with him are not conclusive on whether the letter represents a tongue-in-cheek touch in the film or an actual message to fellow occultists: some details, such as the rapidity of the sequences in which the letter is featured and the employment of rather obvious drawings – a dragon, a skull, a snake – to represent common concepts like death and destruction, seem to point in the first direction. At the same time, however, Albin Grau’s serious and lifelong involvement with occultism and the interest for the mystical sciences that was widespread amongst many German Expressionist filmmakers would appear to be an indication that what we have here is something deeper and much more complex than a simple cinematographic prop.

Knock’s attentive expression and manic laughter contribute to that sense of increasing menace and tension that culminates with the brief dialogue between Knock and Hutter during which the estate agent asks his employee to take care of Count Orlok’s desire to buy a house in Wisborg, a job that may cost Hutter: ‘[…] some effort…a little sweat and…perhaps…a little blood’. After suggesting the young man to offer Orlok the deserted house in front of Hutter’s own place, Knock dismisses him with the recommendation to travel quickly to the ‘land of ghosts’.

The onset stage proceeds to a short sequence concentrating on Hutter’s preparation for his journey to Transylvania. Once again, we have the chance to observe up close the interaction between him and Ellen and to gain further insight into their respective personalities. Hutter’s childish enthusiasm about his imminent journey to ‘the land of robbers and ghosts’ is met by Ellen with a mixture of sadness and foreboding that goes completely unnoticed by her husband. A revealing example of Murnau’s use of space composition to build up and comment on the characters’ personalities and relations is the layered shot of Ellen standing on the left of the frame while Hutter, separated from her by the partition wall, is running back and forth in the background of the image while he is intent to pack his bags. Ellen’s more meditative nature is put here into sharp contrast with Hutter’s superficial eagerness. She appears almost to be physically (and, I would add, also emotionally and psychologically) entrapped in the corner of their heavily Biedermeier-style furnished living room, the open window on her right once again subtly hinting at the possibility of an escape into a different reality. The long shawl draped around her shoulders and her posture increase the sense of claustrophobia enveloping her and the wall between Ellen and Hutter acts as a physical metaphor hinting at a much deeper sort of incommunicability. This short sequence also works circularly by anticipating some of the most important elements of the film’s closing sequence such as the bed where Ellen will die and the gabled houses across the canal from which the vampire will bring disease and devastation to Wisborg.

Figure 2 Ellen’s anguish versus Hutter’s childlike enthusiasm

Also the second segment of the sequence reinforces our impression of a relationship based on routine gestures of affection and on a sentimentality shaped by bourgeois conventions: Hutter almost shakes off Ellen’s concerned embrace turning away from her and the passionate look he gives to his wife shortly afterwards seems to have little credibility when we compare it with the brief and asexual kiss that follows it. After consigning Ellen, who is by now clad in ominously black attire, in the care of a friend and his sister, Hutter finally leaves Wisborg.

A majestic panoramic night shot of the mountains and forests of the Carpathians marks Hutter’s arrival in Transylvania. This shot is particularly important because it can be used to underline a series of major points about Murnau’s approach to cinematography. First of all the director’s predilection for location shooting marks his distance from Expressionism’s obsession on the employment of sets reconstructed in studios. Through the eyes of Murnau natural and urban locations and landscapes go through a poetic treatment and take on deep spiritual – and immensely frightening – resonances that in Expressionist cinema are normally conveyed through the carefully built-up sets. Furthermore, this panoramic view with its strong painterly feeling creates a bridge between Murnau’s work and the Romantic tradition of landscape painting where the panorama is transformed into a mental projection shared by the artist and the onlooker who is invited to immerse himself into the meditative qualities of the landscape that can either be uninhabited or occupied by an isolated Rückenfigur. As we will see in the book’s section devoted to the film’s major themes and techniques, the link between painting and cinema was one of Murnau’s central concerns and it was also an aspect particularly cherished by the Weimar film industry in its attempt to gain and reinforce an aura of cultural prestige.

The rest of the arrival sequence follows what we can now consider the conventional deployment of the onset phase. Hutter checks into a local tavern to eat and spend the night and urges the innkeeper to feed him quickly for he has to move on and reach Count Orlok’s castle. At the very mention of the name, the peasants shudder and recoil in horror and Murnau hesitates on their terrified faces while the landlord warns Hutter of a ‘werewolf’ lurking in the woods. This short sequence is followed by another nocturnal shot of the nature surrounding the inn. In particular, it is interesting to notice the presence of a rather out of context hyena terrifying a pack of wild horses in a nearby field. Kevin Jackson in his recent book on

Nosferatu contends that ‘these shots […] point to one of the extra-narrative properties which gives the film its richness.

Nosferatu is, among other things, a cinematic bestiary’.

40 I would also add that the presence of such an incongruous animal such as the hyena – explicitly wanted by Murnau who added a note to this regard in his copy of the script

41 – enhances that sense of estrangement and mystery that is so essential in the overall development of the film’s narrative.

42From the wide-open space of the outdoor scenes we move into the room where Hutter is about to spend his first Transylvanian night. The room is described as a ‘tiny white-washed room with sharp angles: a flickering light from the […] candle’. It is furnished simply but the bed and the arch motive on the back wall, two elements that will become very important in the castle sequences, are placed in a prominent position and occupy an entire half of the shot. After a rapid sequence during which we see Hutter looking outside his window into the night followed by two more shots of the horses and the hyena and of the old peasant women panicking at the sounds coming in from the forest, the onset phase adds a crucial element to our expectations as to what might happen next in the story. By his bedside, Hutter finds a book on ‘vampires, monstrous ghosts, sorcery, and the seven deadly sins’ and starts reading a page describing a creature of the night known as the Nosferatu:

From the seed of Belial came forth the vampire Nosferatu which liveth and feedeth on the Blood of Mankind and, unredeemed, maketh his abode in the frightful caves, graves and coffins filled with accursed Earth from the fields of the Black Death.

In a medium shot we see Hutter reacting to his discovery of the book. The script reads, in Murnau’s handwriting: ‘Hutter, shaking his head, continues reading’; then back to Galeen’s original: ‘Hutter shuts the book, having lost interest. It seems confused to him. He yawns and puts out the candle.’ His response to the ominous content of the volume is a mixture of amusement and boredom, an attitude that is perfectly in tune with the kind of dismissive and overall shallow personality we have witnessed so far in the film. What we have in this sequence is also a very good example of what Noel Carroll’s defines ‘phasing’:

[…] the audience may put together what is going on in advance of the characters in the story; the identification of the monsters by the characters is phased in after the prior realizations of the audience. That the audience possesses this knowledge, of course, quickens its anticipation […] the audience often is placed in this position because it, like the narrator, frequently has access to many more scenes and incidents, as well as their implications, than are available to individual characters.

43

We fade out to black onto the next sequence that carries us smoothly to Hutter’s morning departure from the inn during which he has the time to dismiss yet again the Book of Vampire and its warnings. Then, through the winding roads in the Carpathians’ forests, we find ourselves up the mountain pass where the coach drivers refuse to travel any further thus abandoning their passenger to his destiny. Finding himself alone, Hutter proceeds to cross a bridge that finally marks his entrance to the land of ghosts inhabited by the Nosferatu. The crossing of a material threshold is a crucial topos in vampire tales and folklore that tend to proceed along that fine and unstable line separating what is real from what is imaginary, what is normal from what is monstrous. Hutter’s passage of the fatal threshold is marked by one of the most famous intertitles in the film:

No sooner had Hutter stepped across the bridge that the eerie visions he had often told me about seized hold of him.

The French Surrealists – starting with André Breton who wrote about Nosferatu in his books Le Surréalisme et la peinture (Surrealism and Painting, 1926) and Les vases communicants (The Communicating Vessels, 1932) – cherished this narrative passage with particular fondness. What they had in mind, however, was a loosely-translated and incomplete version of the original German (‘Kaum hatte Hutter die Brücke überschritten, da ergriffen ihn die unheimlichen Gesichte, von denen er mir oft erzählt hat’) that in its French translation reads as ‘Et quand il fut de l’autre côte du pont, les fantômes vinrent à sa rencontre’ [‘And when he crossed the bridge, the phantoms came to meet him’]. The French version of the title is certainly more evocative and perhaps even more in line with the nightmarish quality that pervades Murnau’s film. However, I find the differences between the two translations to be rather intriguing. The German original stresses yet again the nature of the story as a reported account – later made by Hutter to the anonymous narrator of the story – of the events; his subjective interpretation and subsequent recounting of his adventures are still central. Nevertheless, the intertitle seems to be a bit coy in establishing in an unequivocal manner the supernatural nature of the facts that are being narrated. The very use of the adjective ‘unheimlich’ which basically means ‘un-homely’ and therefore can be translated as ‘unfamiliar’ and ‘weird’ – and by extension ‘uncanny’ – retains the implication that there is still a certain degree of hesitation and ambiguity at this stage in the film when it comes to the interpretation of the events we are witnessing. From this point of view, the French translation, which simply cuts off the last part of the German intertitle, is much more forthright and full of a disquieting poetic intensity: ‘the phantoms came to meet him’: the sights that seize Hutter are not just ‘strange’ or ‘uncanny’ but they are active players in the drama unfolding before our very eyes: they are not simple visions but active supernatural presences. The eeriness of the situation is strongly contrasted by the banality of the shot itself: the bridge is nothing more than a tiny footbridge bathed in a strong yellow tint suggesting a bright daylight. Hutter crosses it with no hesitation and for a fleeting moment he turns towards his left to face the camera – and also us, as the audience – with what appears to be a smiling, almost triumphant, expression.

It does not matter though, how much the set up of the shot or the intertitle attempt to convey a sense of harmlessness or of hesitation as to what is about to happen. We know only too well that, once crossed the footbridge with Hutter, we will have entered into the realm of ghosts and the fact that ‘things ‘look’ the same on both sides of the bridge – whether one side represents the ‘normal’ world while the other harbour phantoms […]’

44 – makes the situation even more terrifying.

A sinister night shot of Orlok’s castle precedes a quick sequence in which we see a coach moving in fast motion along the mountain road. This scene is crosscut with another one showing Hutter proceeding on foot towards the meeting point with his mysterious host. A long shot of a ‘snakelike bend’ presents Hutter as a diminutive Rückenfigur in the bottom-right corner of the screen. For a few seconds, we observe him as he looks towards the dense forest through which the carriage will soon come, approaching from the top part of the screen. A medium shot of Hutter’s face alerts us of his astonishment in seeing the odd creature driving the carriage. Henrik Galeen’s thus describes the coach and its driver in the film’s script:

[…] A black carriage. […] Two black horses – griffins? Their legs are invisible, covered by a black funeral cloth. Their eyes like pointed stars. Puffs of steam from their open mouths, revealing white teeth. The coachman is wrapped up in black cloth. His face pale as death. His eyes are staring at Hutter.

45

With a commanding gesture, the driver invites the now hesitant Hutter to climb inside the carriage that with a narrow U-turn quickly gets back on its way. A close-up shot on a distressed Hutter introduces the viewer to one of the most famous sequences in the film during which, in Murnau’s words, the ‘Coach drives at top speed through a

white forest!’.

46Figure 3 The ghostly coach riding to Orlok’s castle

It is interesting to see how Murnau exploits here cinematic technology – and thus by extension modernity, rationality and progress – to finally introduce the supernatural element into his film. The distortion of reality needed to cause fear and dread in the spectator is achieved not by a pre-styled and reconstructed landscape placed before the camera in the style of Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, 1920) but by the way Murnau photographs and edits his natural locations. The washing out of colour turns the natural world into a spectral double whose features seem to resonate with the words used by Maxim Gorky in an article written in July 1896 a few days after his first encounter with the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph:

Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows. […] It is a world without sound, without colour. Every thing there – the earth, the trees, the people, the water and the air – is dipped in monotonous grey. […] It is not life but its shadow, it is not motion but its soundless spectre. […] Carriages coming from somewhere in the perspective of the picture are moving straight at you […] And all this in strange silence where no rumble of the wheels is heard […] Nothing. […] It is terrifying to see […].

47

The use of fast motion to convey fear was obtained simply by the under-cranking of the camera. Rather interestingly, though, this technique did not find many imitators in following films because it became rapidly associated with slapstick comedies that employed acceleration exactly for the opposite reason: to attain humorous effects. In his audio commentary to the BFI edition of the film, Christopher Frayling underlines how ‘Murnau’s aesthetic here is exactly the opposite of the cinema of the last few decades, which (broadly speaking) uses fast motion for comic effect and slow motion to intensify dramatic impact’.

48 It is also interesting to notice how the entire ‘carriage sequence’ and more specifically the use of fast motion to signal the arrival of the Nosferatu in the film presents a series of subtle and intriguing elements that resonate with the equivalent passage in the first chapter of Bram Stoker’s novel when Jonathan Harker is travelling by coach to the Borgo Pass where he is supposed to meet his host. The coach soon arrives at the Pass but there is no carriage waiting to ferry Harker to his final destination. Just as the driver offers to bring him back to the pass the next day, however,

[…] amongst a chorus of screams from the peasants and a universal crossing of themselves, a caliche, with four horses, drove up behind us, overtook us, and drew up beside the coach. I could see […] that the horses were coal-black and splendid animals. They were driven by a tall man, with a long brown beard and a great black hat, which seemed to hide his face from us. I could only see the gleam of a pair of very bright eyes, which seemed red in the lamplight, as he turned to us. […] As he spoke he smiled, and the lamplight fell on a hard-looking mouth, with very red lips and sharp-looking teeth, as white as ivory. One of my companions whispered to another the line from Burger’s ‘Lenore’: - ‘

Denn die Todten reiten schnell’ – (‘

For the dead travel fast.’) The strange driver evidently heard the words, for he looked up with a gleaming smile.

49

The line quoted in the passage is rightly attributed to Gottfried August Bürger’s poem Lenore, a dark tale of love and death first published in 1773 that is often considered one of the first examples of ‘vampire poems’. The work, although often derided and parodied, remained very popular in Germany well after its first appearance and it would be pretty safe to assume that Murnau was familiar with it and that it would be possible to identify a subtle allusion to the poem – whose line, rather interestingly, should actually be translated with ‘for the dead ride fast’ – in this iconic sequence from the film.

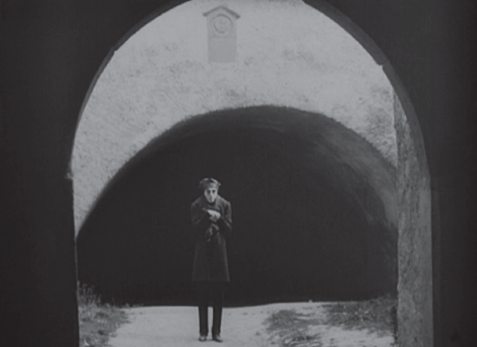

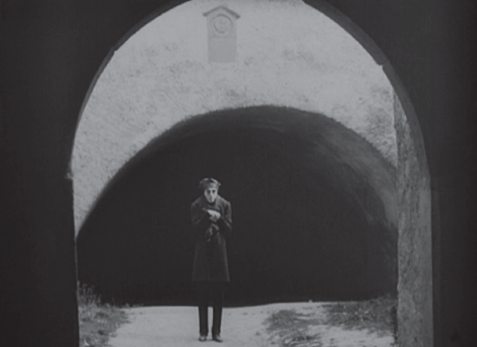

In the following scene a sustained iris shot accompanies us to Nosferatu’s castle. The mysterious driver of the demonic carriage with another commanding gesture propels Hutter towards the entrance and we get to see the castle for the first time in a close-up shot: it appears like a solid white façade with a pointy black roof and a solitary small window slightly off-centred. Hutter is thus faced by another – even more momentous – threshold to cross and stands for a handful of seconds in front of the massive wooden door that slowly opens of its own accord allowing him to enter the castle’s grounds. A subtle arch motive – that reprises the design of Hutter’s bedroom at the inn and that will soon be replicated a number of times within and without the castle – surmounts the building’s entrance. Just like in the preceding sequence at the edge of the ghostly forest, Murnau frames his character in a low angle shot presenting him to us as a powerless Rückenfigur, dwarfed this time not by nature but by the architectural weight of Nosferatu’s fortress and by implication by the destiny that awaits him there.

A reverse shot takes us inside the castle’s courtyard that appears to be a rather enclosed space limited by two overlapping arches. Our sense of perspective is further stifled by the pitch-black darkness that we perceive at the furthest end of the shot. It is from this bleak, dark hole that the Nosferatu appears as himself for the very first time: he is a lanky, black-clad figure walking stiffly in our direction, his pointy silhouette strangely replicating the symbol carved in the top part of the screen. When he stops in the middle of the scene the straight-on angle shot lingers on him long enough to make us feel observed and disquieted by his inquisitive and unrelenting eyes that from a distance look like two tiny black holes – even though we know on a rational level that he is waiting for Hutter to arrive, we cannot help but sense a mixture of attraction and repulsion towards that figure that appears to be looking directly at us.

Figure 4 Count Orlok carefully framed inside a series of arches

A cut and another reverse shot take us back to Hutter who is still coming through the castle’s gate – yet another arch motive dominates the scene. As we observe him looking around while moving towards the camera, from the privileged position of the high angle shot, we can also see the gate closing behind his back and Hutter jumping at the noise of the slamming doors. It is interesting to notice how the entire sequence, although shot outdoors, is characterised by a powerful sense of claustrophobia. Murnau encloses the space at his disposal within the tight confinement of the arches and through the use of very limited perspective and depth of field. There is always some physical obstruction – the darkness, a wall, the castle’s gate behind Hutter’s back – that prevents our eyes from wandering further away from the immediate horizon: as soon as he steps into Nosferatu’s abode, Hutter – and us along with him – get entangled in his spinning web. When Hutter finally meets Orlok, the two characters are framed in a medium close-up that emphasises both the Count’s physical grotesqueness – his long nose, his bushy overdeveloped eyebrows – a real masterpiece of cinematographic make-up envisaged by Albin Grau – and his overpowering presence and authority over his guest who gets told off for having kept the Count waiting ‘almost’ (as specified by Murnau in the film’s script) until midnight. With Orlok preceding Hutter by a few steps, they move towards the arch from where the Count has previously appeared and get swallowed up by its darkness thus completing the film’s first act.

The second act in the film opens on an interior shot of the castle’s dining room. Galeen describes it as having ‘Gigantic dimensions. In the centre a massive Renaissance table. Somewhere in the distance a fire place.’

50 While Hutter is eating, Orlok reads with great attention the mysterious letter previously seen in the hands of Knock.

The back page of the letter shows a confusion of numbers, legible and illegible letters. The holy number seven is repeated several times. In between, cabbalistic signs. The spindly fingers holding the letter cover up the rest like claws.

51

Hutter seems mesmerised, ‘spell-bound’ according to the script, by the sight of his host and, scared by the skeleton clock striking midnight; he cuts his finger while absentmindedly slicing some bread. This is an iconic and often reprised scene that appears in numerous Dracula’s adaptations: for the first time, excited by the sight of the ‘precious blood’ flowing from Hutter’s finger, Nosferatu appears to us in all his feral nature. He gets up from his chair and starts moving towards his guest in a threatening way and grabbing Hutter’s hand, he attempts to lick the blood away. What ensues is a pseudo-assault during which Hutter pressed on by Orlok is forced to retreat all the way to the fireplace at the back of the dining room. There, going against our expectations, Orlok suggests to an astonished Hutter to spend some time together talking because during the day he sleeps ‘the deepest of sleeps’. Duly executing another of Orlok’s commanding gestures, Hutter sinks back on the chair behind him: he is nothing but a marionette in the hands of the Count.

The following sequence opens on an intertitle heralding the arrival of the new day that seems to suggest between the lines that Hutter may have been the victim of some sort of nightmare:

Just as the sun rose, the shadows of the night withdrew from Hutter as well.

An iris out presents us with Hutter still slumped on the chair where we saw him falling the previous night. The mise-en-scène and the character’s body posture almost appear as a mirror image of the famous Pre-Raphaelite painting by Henry Wallis The Death of Thomas Chatterton (1856) that depicts the tragic passing away of the young Romantic poet.

However, Hutter is not dead and stretching his limbs after a disturbed night of sleep, he starts looking around himself being clearly pleased to see the dining room filled with the bright light of the new day. The following sequence reiterates one of the principles of the onset phase in horror films. Hutter seems to sway between the reassurance provided by the now normal-looking surroundings and the suspect of having been the victim of some mysterious attack. He discovers two tiny punctures on his neck and once again we see a close-up of his face in a small mirror in a scene reprising the opening sequence of the film. And yet, his suspicions are still easily discarded – ‘He yawns once more’, underlines Galeen in his script.

52 The luscious food prepared on the table is enough to dispel the bad dreams left over by the night and the castle’s grounds, surrounded by beautiful forests, seem to be genuinely enjoyed by Hutter who finds himself a cosy spot to write a letter to Ellen. We are still in the phasing stage of the film: our knowledge of what is going on is still a few steps ahead compared to Hutter’s. A clear example of this staggered release of information can be found in the letter sequence when Hutter mistakenly connects the punctures on his neck with the harmless mosquitoes that seem to plague the place and his general sense of bewilderment to the ‘heavy dreams’ caused by the castle’s desolation.

A night shot of the forests surrounding the castle – ‘another Friedrich moment’

53 – introduces the audience to what can be considered the final section of the onset phase during which events, until now so slowly and carefully presented, will finally take a precipitous turn. The introductory intertitle speaks of the coming of the ‘spectral evening light [that] seemed to revive the shadows of the castle’ and we return again to the dining room where Hutter and the Count are busy perusing documents and papers. The accidental dropping on the table of a locket containing Ellen’s portrait attracts Orlok’s attention. He looks at it with wild manic eyes and remarks on the woman’s beautiful neck before signing the contract that finalises his acquisition of the deserted house opposite Hutter’s. This brief sequence marks Hutter’s first glimpse of awareness of what is about to come: Orlok is not simply an isolated eccentric loner but a far more menacing creature whose direct link to the Devil is clearly established in the script: ‘[…] a satanic look has come into his eyes. His hands have turned into claws’.

54A cut takes us to Hutter’s bedroom. He kisses softly Ellen’s picture and, putting it back into his bag, he is surprised to find in it the book on vampires already seen at the inn. Taking up from the previously read pages, the following two intertitles provide Hutter with further clues about what really goes on at the castle:

At night this same Nosferatu doth clutch his victim and doth suck like hellish life-potion its blood.

Take heede that his shadow not encumber thee like an incubus with gruesome dreams.

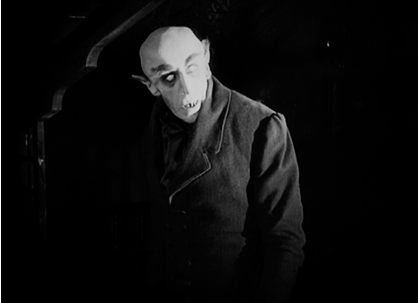

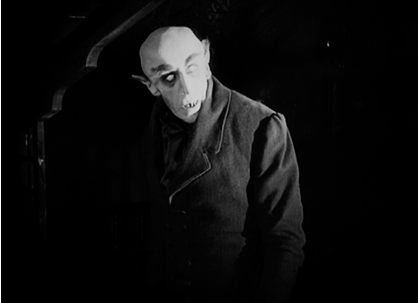

Made suspicious by the words in the book, Hutter runs to his bedroom’s door to look into the dining room: a long shot that goes deep into the dining hall and is immediately followed in dissolve – the only one used in the film – by a medium close-up offers to us the terrifying vision of Orlok as ‘a gigantic vampire, a motionless, sombre watcher in the night’.

55 He is standing in front of the fireplace and looks in Hutter’s direction bareheaded, with a fixed gaze and its sharp teeth laid bare. Terrified by the vision, Hutter shuts the door, that has neither locks nor handle, and looks for a way out. The shadows engulfing the bedroom transmit an acute sense of claustrophobia and the room’s only window opens up on a steep cliff. Hutter, suddenly reverting to a scared child, scrambles towards the bed in search of safety and he is just in time to see the vampire appearing in the doorframe before literally hiding under the covers. In this shot, Orlok’s body appears to be perfectly framed within the door’s arch and, with the door wide open on the left side of the screen, the overall impression given by the image is that of a propped-up coffin which has suddenly sprung open uncovering the corpse inside it.

At this exact point, the linearity of the events taking place in the castle is interrupted and, through a quick informative intertitle, the action is moved to Ellen’s bedroom in Harding’s house in Wisborg. The sequence that follows demonstrates a masterful use of cross-cutting. The action, although very cohesive from a chronologically and covering only a handful of minutes, is split spatially between Wisborg and the castle in the Carpathians and its narrative focus alternates between Ellen and Orlok.

Figure 5 Orlok framed in the coffin-like door of Hutter’s room

At the beginning of the cross-cut section, we see Ellen getting up from her bed and, attracted by a mysterious force, leaving her bedroom to sleepwalk on the ledge of Harding’s balcony. In a secondary cut of the same segment, she is rescued by Harding who also orders to summon a doctor. Back at the castle, Orlok is now attacking Hutter. On the screen we see the shadow of the vampire’s claws slowly creeping up on his victim in an image that anticipates the film’s closing sequence. We revert back to Ellen, now in bed and surrounded by Harding, his sister and the doctor. She wakes up, sits on the bed and looks off-screen left with a frantic look on her face and starts shouting her husband’s name. Back again to the castle: Nosferatu’s shadow is moving down towards Hutter who is lying on the bed where he appears to be motionless and unconscious. Unexpectedly, though, the vampire stops and turns around in a left to right direction and with another rapid cut we are transported back to Ellen who in seen in the same pleading position as before. Has the Nosferatu ‘heard’ the woman’s desperate call? The script reads:

Nosferatu turns his head. He is listening intently as if he could feel – hear the [in Murnau’s handwriting] terrified shouting in the distance.

56

The following shift shows him slowly leaving Hutter’s room and the entire sequence is closed by the image of an exhausted Ellen who is slowly recovering from what the doctor dismisses as ‘harmless congestions of the blood’. This layered sequence is immediately notable for its technical achievements and for the powerful way in which Murnau exploits cinematographic cross-cutting. It is also very important, however, because of its narrative implications: on the one hand, it triggers that frantic and desperate rhythm that will characterise the second part of the film, which will be often constructed along parallel narratives and events revolving around different characters in the story; on the other hand, it also establishes the fundamental psychic link between Ellen and Orlok – who appears to be looking at each other in the sequence’s last few segments – that will be at the basis of the film’s subsequent events

Figure 6 Cross-cutting: Orlok is distracted from his victim by a mysterious force.

The link between Ellen and the Nosferatu is also established clearly by the following intertitle, another extract from the narrator’s chronicle:

The doctor related Ellen’s distress to me as an unknown illness. I know, however, that her soul that night caught the cry of the Deathbird - Nosferatu was already spreading his wings.

Figure 7 Ellen appearing to plead mercy to the vampire

The link between Ellen and the Nosferatu is also established clearly by the following intertitle, another extract from the narrator’s chronicle:

The doctor related Ellen’s distress to me as an unknown illness. I know, however, that her soul that night caught the cry of the Deathbird - Nosferatu was already spreading his wings.

THE DISCOVERY PHASE

Proceeding in his analysis of the ‘complex discovery plot’, Noel Carroll describes the discovery phase as the moment when

The onset of the creature, attended by mayhem or other disturbing effects, raises the question of whether the human characters in the story will be able to uncover the source, the identity and the nature of these untoward and perplexing happenings.

57

It is important here to clarify how the discovery phase properly occurs only when it is established beyond any doubt that there is a monster or some supernatural occurrence at the bottom of the problem. In the case of Nosferatu, the moment of the discovery can be neatly isolated against the rather extended onset phase during which all the disquieting events directly or indirectly connected to the presence of the vampire had time to pile up before Hutter had any idea of what may be going on.

The quick investigative phase during which Hutter sets out to discover more about the ‘horror of his nights’ is bracketed by two hauntingly beautiful outdoors night shots marking the sunrise and sundown of his third day in Nosferatu’s castle. Suddenly awaken by the daylight, Hutter jumps out of bed clutching his throat and runs out of his bedroom to investigate the castle. We see him running through the pointed arch of his bedroom’s door where we last saw the vampire but this time the door is completely removed from the surrounding environment and appears isolated in the middle of a totally black screen. Once again, the door works as a threshold into the supernatural realm of the vampire: in the preceding sequence Nosferatu was framed in it looking like a corpse in his coffin and in this sequence the unnatural seclusion of the passage strongly suggests that Hutter is not crossing an actual door but rather a portal towards the vampire’s nightmarish dimension. The long shot encasing the castle’s dining room emphasises the eeriness and isolation of the place.

Attracted by an invisible force, Hutter exits the room and rushes to the castle’s basement where he finds an old wooden coffin containing the body of the Count suspended in his un-dead state. Although at first only visible past the sarcophagus’ battered lid, the close up on Nosferatu’s face, with wide open eyes and sharp fangs showing through the half-open mouth, is nothing short of terrifying.

Hutter backs off in horror but gathering again his courage, pushes away the coffin’s lid thus exposing the vampire’s full body: his pale face and long spindly fingers are emphatically visible against the darkness of his black coat. Hutter’s reaction at this vision of horror is one of pure, unmitigated terror. He recoils and falls on the stone staircase behind him and scrambles up the steps without even being able to stand on his feet. After another iris shot of the forest indicating the approaching of the night, we find Hutter slumped on the pavement of his bedroom with a look of bewilderment and fear depicted on his face – ‘[…] His body is twisted with fear. His hair is standing on end…’

58. A noise suddenly shakes him from his stupor and looking out of the window he sees, once again in fast motion, Nosferatu loading some coffins onto a cart that dashes off as soon as the vampire has climbed into the topmost sarcophagus. Understanding immediately that Nosferatu’s departure will pose a mortal danger to Ellen, Hutter starts ripping off the sheets of his bed to make a rope that will enable him to run away from the castle. Murnau shots him in a close-up while he attempts to climb down the steep walls and then when he crashes to the ground below where he eventually falls unconscious. The frantic pace of the first part of the discovery phase slows down during this last sequence of the film’s second act, a beautiful and deceptively peaceful long shot of a flatboat going down a wide river lined by luscious greenery:

The river flows majestically through the immense plain.

The scenery is bathed in sunshine.

All is peaceful.

Then a large raft appears round a bend in the river and floats slowly into view.

Boatmen with long poles are pushing it with considerable effort. At the stern a high pile of boxes. Black, coffinlike boxes. Stacked into a pyramid. An uncanny sight. [Indefatigably, the boatmen go on punting.] The raft is coming closer and closer – like doom.

59

This vision of approaching disaster lingers on in the mind of the spectator well into the beginning of the film’s third act that, again by means of a masterful use of the crosscutting technique, follows five different narrative strands that work together as a tightly-knit whole in order to conjure and build up the events that will be at the basis of the final two phases in the film: the confirmation stage – although, as we will see, this will never be fully developed in the course of

Nosferatu – and the confrontation phase. The opening sequence of Act III is reserved to Hutter whom we see recovering in a non-descript hospital room (that the script situates in Budapest) where he is assisted by a nun and a doctor. Waking up suddenly from a feverish sleep, Hutter clutches the nun with an expression of terror on his face while shouting the word ‘coffins!’ A quick insertion of two intertitles connects this opening segment to the second narrative strand of the act that will focus on the tragic journey of the ship

Empusa and its crew from Galaz to Wisborg. Although called

Demeter, as in Stoker’s novel, in the original script, the ship that will bring Nosferatu to Wisborg was renamed

Empusa during the making of the film. As pointed out by Kevin Jackson in his book, it would be safe to assume that the rather obscure reference to the

empusa, a Greek semi-goddess who feasts on the blood of young men while they are asleep, can be probably regarded as a contribution by Albin Grau to the film’s virtual list of intertextual references, along the lines, for instance, of the allusion to Burger’s poem

Lenore in the sequence of the fast moving ghostly white carriage discussed earlier in this chapter.

60 The quayside sequence starts off with a routine check of the ship’s cargo – six crates of earth (and not simple sand, as Murnau points out twice in the script) for experimental purposes – that turns out to contain more than just soil: a multitude of rats swarms out of the box that has been opened for controls by the port’s authorities. The viewer is here invited to make an immediate – although perhaps still subconscious – connection between the rats and those stories chronicling the spreading out of plague epidemics by means of sea travels. The implication seems clear: it is not just Nosferatu who is coming to Wisborg: he is also carrying the plague in his trails.

In a first apparent non sequitur, the dockyard sequence is linked to the third set of action of this narrative section of the film. Back to Wisborg, Professor Bulwer, the Paracelsian doctor whom we saw briefly with Hutter at the beginning of the film, is giving a lecture on the dark side of nature to a small group of his students. In a rapid sequence made up of four short segments, Murnau puts into connection the various examples of predators (a Venus flytrap, a polyp with its tentacles, and a spider) selected by Bulwer and presented to the audience through clips – beautifully tinted and shot in micro-cinematography – taken from scientific films with the predatory madness of the estate agent Knock (who, in the meantime, has been secluded in an asylum), and more widely with the now-approaching Nosferatu.

While Bulwer describes the Venus flytrap eating a fly by comparing it to a vampire, the film cuts to Knock who, equally, is catching and eating flies in front of the bewildered doctor Sievers. This parallel between the rapacious side of the natural world and the greed for blood (‘Blood is life!’ exclaims Knock in the sequence) of the vampire and of his slave will be reiterated two more times through the examples of the incorporeal – ‘almost but a phantom’ – polyp feeding off a microscopic organism and the spider entangling an insect in its web. The connection is particularly intriguing and

Just as Bulwer compares the carnivorous plant to the vampire, Murnau’s editing compares the madman and the scientist, each the center of a dark system of deadly metaphors and hysterical imitations.

61

Although pertaining to the limbo between life and death, Nosferatu, suggests Murnau, is also a manifestation of the dark side of the natural world: he maliciously preys on living things, like the carnivorous Venus flytrap or the spider; just like the polyp he can make himself incorporeal and his natural voyage companions are the rats travelling with him in the boxes full of his native Carpathians’ soil.

The following segment acts as a short melancholic interlude that shifts the film’s narrative focus from the vampire to Ellen. A quick set of intertitles provide the set-up for what is about to come:

Ellen was often seen on the beach within the solitude of the dunes. Yearning for her beloved, her eyes scanned waves and distance alike.

An iris out presents her to the audience in a medium long shot while she is sitting on a solitary bench along a windy beach dotted with several crosses bent by the relentless wind. The original script – which, slipping back into Stoker’s novel, names the place as ‘the graveyard of Whitby’, a mistake that was subsequently corrected by Murnau to ‘Heligoland’ – suggests a rather different set up for the scene:

[…] a long row of benches. People are strolling up and down looking out on to the sea…sitting on the benches and enjoying the view.

62

Compared to the much more mundane initial idea suggested in the script by Galeen, what we have on film is an infinitely more haunting and melancholic representation. Ellen’s solitude and concern are heightened by her physical isolation from other human beings and also by her demeanour and attire. She appears on the beach in the attitude of a Rückenfigur – thus investing the sea with the extra function of becoming a mirror for her turbulent state of mind – and the beach seems to be completely devoid of other signs of life and is on the contrary full of reminders of death and loss (e.g. the crosses, the black dress). Amongst the crosses, Ellen appears as an authentic ‘woman in black’ who is more likely to be mourning someone’s passing rather than waiting for someone’s return. The desolation of the scene is almost immediately contrasted with the cheerful images of Harding and his sister playing croquet (another of Murnau’s specific requests apparent from one of his handwritten corrections in the script) in the garden of their villa. Their game is interrupted by an old servant who has just received a letter from the postman. Realising that the letter is indeed from Hutter, Harding and Anny rush to the beach to consign the letter to Ellen in the hope of giving her some relief from her distress.

Figure 8 Ellen longing for her lover

A series of outdoors views of the wavy sea and of the wind-battered sand dunes contribute to increase even further the sense of isolation and solitude conveyed by the location and it is also interesting to notice how differently Murnau presents the two female characters in the sequence. Despite being clearly the same age, Ellen looks old and world-weary when compared to Anny who is described in the script as ‘glad’ and ‘quick’ and ready to burst into ‘a joyful laugh’. The contrast between them is not simply marked by the black versus white attires the two characters are wearing but it is also conveyed by their body posture and general demeanour. Feeble and burdened by worries, Ellen does not even have the strength to get up when she sees Harding and Anny approaching and, even more importantly, she refuses to open and read Hutter’s letter asking instead Anny to do it on her behalf. The following intertitles present to us the letter we saw Hutter writing after his first night at the castle. Images of Anny reading the letter alternate with medium close ups of Ellen listening intently to its contents. At the mention of the ‘mosquito bites’ troubling Hutter, though, something seems to stir Ellen into action: she grabs the letter from Anny’s hands and finishes her reading. Clearly sensing something untoward – and thus confirming the impression of a supernatural psychological link between her and the Nosferatu already hinted at during the sequence of the second assault on Hutter – Ellen gives way to her fears and leaves the scene running away from her bewildered friends.

By means of another jump in location, we are back in Budapest where Hutter is trying to recover from his ordeal, just in time to see him leave the hospital room directed home ‘by the shortest route’. Hutter’s departure is followed by two quick sequences suggesting the competition between him and Orlok in their rush to get to Wisborg: in the first sequence the Empusa is filmed while it is slowly crossing the screen right to left. Alone in the open sea and apparently devoid of any life (there are no sailors visible on the deck) the ship is a stark reminder of the doom looming over Ellen and the rest of the population in Wisborg. In contrast with the ship’s smooth sailing, the next scene shows Hutter leading his horse through a dense and intricate portion of vegetation where his movements appear to be particularly difficult. As if to reiterate and underline the smoothness of the vampire’s journey – because quite clearly the dead not only ride but also sail fast – Murnau intercuts another shot of the Empusa crossing again the screen right to left. Nosferatu’s advantage over Hutter appears now to be obvious and insurmountable. The film’s incessant cross-cutting continues and through an iris out we are back into Knock’s solitary cell where we see him steal a newspaper from the back pocket of an asylum attendant. Once alone, Knock ‘unfolds the paper [trembling with expectancy] and starts reading [searching for something] with wide-open eyes’.

63 The subsequent intertitle reproduces the newspaper’s page chronicling the explosion of a plague epidemic:

PLAGUE. A plague epidemic has broken out in Transylvania and the Black Sea ports of Varna and Galaz. All victims exhibit the same peculiar stigmata on the neck, the origin of which still puzzles the doctors. The Dardanelles were closed to all ships suspected of carrying the plague.

As a side note, it is interesting to notice that the edition of the film released by Eureka has omitted one line from the English translation of this intertitle. Where the original German title reads: ‘Junge Leute warden in Massen hingerafft’ (‘Young people are being swept away in large numbers’) the English intertitle jumps straight onto the next line. It is an omission that I tend to attribute to a simple oversight but that it nevertheless detracts from the chronicle another disturbing detail connecting Nosferatu to its young, unsuspecting victims that adds a further note of meaningless tragedy to the whole story. The sequence closes with a triumphant-looking Knock who smiles with ‘an expression of demonic grandeur’ knowing that the plague is no coincidence but it is the signal marking Orlok’s arrival.

64 Another alternation of Hutter’s slow journey by land and of the Empusa – now filmed through a series of dramatic close-ups of its sails that enhance the looming character of the ship – anticipates a longer sequence taking place on the ship where we see one of the crewmen alerting the Captain to the fact that one of the sailors has fallen ill and is below deck in a delirious state. After paying a quick visit to the sailor, the Captain and the mate leave him alone to rest in the ship’s hold. The change, from amber to blue, in the image’s tint suggests the passing of time. It is now night and the sailor turning around towards the boxes that have always been visible lurking in the background of the shot, is terrified by the vision of an incorporeal image of Nosferatu hovering over the coffins. A new cut takes us back again to Hutter who is now seen dragging his horse that appears to be slightly limping on the rugged terrain.

The following intertitle will inform us of the tragic destiny of the crew travelling on the Empusa:

It [the plague] spread through the ship like an epidemic. The first stricken sailor pulled the entire crew after him into the dark grave of the waves. In the light of the sinking sun, the captain and ship’s mate bid farewell to the last of their comrades.

Back on the ship’s deck and after the sombre burial at sea of the last crewman, the ship’s mate grabs an axe and prepares to go below deck. An intense profile close-up communicates his resolve to see into the curse that has befallen on the ship even though his attitude is contrasted by the captain’s resigned demeanour. Another quick intercut back to Hutter: he is now riding his horse ‘at tremendous speed’ left to right across the screen and along a desolate plain. Back on the Empusa and this time below the ship’s deck. The mate starts axing away at the coffins only to be met by swarms of rats until we see him freezing in a pose of surprise and terror. In a reverse shot introducing one of the most famous sequences in the film, we see the reason of his reaction: stiff as a corpse, a terrifying Jack-in-the-box, Nosferatu springs up from one of the coffins in ‘an image simultaneously suggesting erection, pestilence, and death’.

65In a mad panic, the mate rushes back to the deck and throws himself in the water under the astonished eyes of the captain. The destiny of the Empusa is now about to reach full circle and Murnau films it at a relentless pace: we see the captain binding himself with ropes to the wheel – ‘Thus he awaits the horror…’

66 – in one last desperate attempt to remain at his place of command until the end of his doomed journey and immediately after Murnau frames Nosferatu walking across the deck in a low angle shot from the ship’s hold. The lack of any real depth in the image and the ship’s masts framing the black and lanky silhouette of the Count increase the sense of tragedy and domination already conveyed by the situation.

Before finally fading to black, the lingering shot on the terrified captain tells us without showing anything of all the horror of his final demise. The following intertitle – ‘The ship of death had acquired its new captain’ – along with the long ‘contre jour’ shot of the Empusa that appears majestic and black against the night sky conclude the film’s third act on a note of doom and tragedy that is however not entirely devoid of an underlying sense of awe and poetic beauty that Kevin Jackson interestingly connects to Edmund Burke’s definition of the ‘Sublime’ as ‘[a] mode of beauty associated with awe, fear and even pain rather than health, pleasure and calm.’

67Figure 9 Low-angle shot of Orlok taking possession of the Empusa

The opening minutes of the film’s fourth act employ again the cross-cutting technique to build up the narrative tension for Nosferatu’s arrival in Wisborg. Taking its cue from an intertitle underlining the supernatural origin of the ship’s movement – ‘Nosferatu’s deadly breath swelled the sails of the ship, which flew on toward its destination with ghostly haste’ – and from a sequence filmed from the ship’s prow that could be compared to an eerie version of early phantom ride films (during which a camera mounted on the front of a moving vehicle would take the audience on journeys to exotic locations and foreign countries), the images cut quickly to Ellen who is about to fall prey to another attack of somnambulism and subsequently to the stormy sea – thus underlining once again the connection between her and the vampire – and finally to Hutter who is now seen approaching home travelling on a coach. Awoken by the storm, Anny gets up to look for her friend and finds Ellen in a semi-trance on the villa’s terrace.

Figure 10 A contre-jour shot of the ship of death

Her words – ‘I must go to him. He’s coming!!!’ – intercut both with images of the Empusa and of Hutter on his way to Wisborg have often struck the film’s commentators as being deeply ambiguous. Who is Ellen really talking about? Who must she meet so urgently? The psychological link between her and Orlok, along with what has been seen by some as a possible erotic infatuation for the repulsive but ultimately animalistic character of the vampire, a figure that traditionally presents strong sexual undertones, complicate and muddle a simple interpretation of Ellen’s words. Although it is true that this sense of ambiguity is resolved on a pure narrative level by placing strategically a sequence focusing on Hutter after the intertitle with Ellen’s words, this uncertainty cannot be shaken off easily and is subtly reinforced by the fact that Murnau alternates close ups of Orlok’s ship with long shots of Hutter’s journey, thus giving the impression that Ellen’s urgency is in fact due to the incoming schooner and not the arrival of her husband who seems to be – also on a simple visual level – still far away from his final destination. Another cut on the Empusa, filmed this time from a different angle, is followed by Ellen running out of the house in her nightgown and by a sequence focusing on Knock who, guessing the arrival of Orlok, is growing increasingly agitated.

The scene in the mental asylum is followed by another one of the film’s iconic sequences: in a long and sustained shot Wisborg’s harbour is obliterated by the ‘dead and forsaken’

68 ship that slides ominously right to left across the screen virtually cancelling all signs of human life from the town in its path. Knock senses that Orlok has finally arrived in town. Cut back to the Empusa where the ship’s hatch gets lifted by a mysterious force: Nosferatu, showing a malicious grin on his face, peaks out of the hatch while Knock manages to escape from the asylum.

Framed in the archway of one of Wisborg’s medieval doors, ‘Nosferatu, coffin under his arm [is] looking around to orientate himself. Then he strides on’.

69 Swift cut on his rats that are now seen swarming out of the ship. Through another quick parallel montage, Murnau films Hutter’s and Orlok’s end of the journey: whilst Hutter finally reunites with Ellen, who collapses in his arms on the threshold of their home, Orlok keeps striding through Wisborg. We see him passing through the little square with the fountain that we saw twice at the beginning of the film and then stopping knowingly just outside the house of the unsuspecting couple who are overpowered by the happiness of their reunification. Cut to the empty warehouse opposite Hutter’s: Nosferatu is slowly approaching it crossing the canal on a small barge. Using again his background in art history for inspiration, Murnau frames and films the action in such a way that the entire sequence can be read as a clear and unmistakable homage to Arnold Böcklin’s painting

Isle of the Dead (1866). The nocturnal spectral quality of the scene is conveyed visually by the supernatural movement of the little boat that appears to glide across the water by itself while the figure of the vampire stands still in the darkness. Once outside the warehouse, the vampire will simply disappear into it by means of a very effective and eerie image dissolve.

The morning after Nosferatu’s arrival in Wisborg the town authorities find themselves facing the riddle of the Empusa. In a rather short but lively sequence, Murnau films Harding and other dignitaries investigating the empty schooner, and collecting the ship’s log and the captain’s diary to try and unravel its mystery. In the town hall, where the mise-en-scène recalls the famous painting by Rembrandt the Anatomy Lesson (1631), the doctor and the other men examine the body of the dead captain and the two tiny punctures visible on his neck. We see Harding reading from the ship’s log about rumours of a ‘strange passenger’ hiding on board and about the presence of rats in the ship’s hold. The conclusion seems obvious: the crew has been exterminated by the plague carried by the rats. Panic strikes: the men quickly leave the town hall, some of them covering their mouths with a handkerchief. The closing sequence of the film’s fourth act plants a note of quiet desperation in the mind of the viewer. An iris out is followed by a long shot of a steep and deserted street: the radical sense of perspective, which is stretched out to a haunting and almost irrational extreme, and the heavy shadows occupying a prominent portion of the shot convey a sense of stifling narrowness and immobility. The only person about town is the local crier who reads out a proclamation on how to act in order to contain the plague epidemic; Murnau lingers with his camera on the terrified faces of various citizens who start retreating hastily indoors at the mention of the plague.

The film’s final act opens up with a short sequence chronicling the macabre business of counting the victims of the plague epidemic. An iris out introduces a medium shot of an old town official checking out a row of houses and marking with a white cross the doors of those places where people have been afflicted by the plague – a group of black-clad pallbearers is filmed while carrying out a coffin from one of the homes. A new intertitle moves the action back to Ellen and Hutter:

Hutter made Ellen swear not to touch the book which had frightened him with its visions. - Yet she could not resist its bizarre attraction.

In a close-up shot we see Ellen reading the Book of Vampire, her agitation, along with a creeping sense of awareness, increasing after each word. The pages of the book are projected onto the screen and thus we discover that the only way to defeat the vampire is through the sacrifice of ‘a maiden wholly without sin [who] maketh the Vampyre forget the first crow of the cock’ by giving ‘freely of her blood’. At this point Hutter comes into the room and ‘with agitation, almost hostility he grabs the book’ from Ellen’s hands.

70 In his gesture, and in his warning not to even touch the book - we can read another trait of Hutter’s typical lack of maturity and perspective, as if ignoring the shadows would be enough to make them go away. Ellen shakes away from his embrace and turns to the window pointing out nervously towards the empty houses that can be seen in the image’s background. Desperately and almost impatiently, she shows to her husband what she has been seeing every night through her window: a long shot of the empty warehouses and, almost indistinguishable behind one of the windows on the left of the shot, Nosferatu looking in her direction.

Hutter runs to the window but shakes his head in a desperate act of disbelief; Ellen walks slowly away from the room leaving her husband fall onto the bed in complete desperation. The script underlines here in a very effective manner the gap in knowledge and awareness experienced by the two characters:

[Ellen] knows all she has to know. Hutter has not come to that yet. He finds her calmness disturbing. He follows the retreating figure with his eyes. […] Hutter, despairingly, presses his fists against his face.

71

The whole sequence leaves the viewer with a series of open questions. Why is Hutter so stubborn in denying what it is really going on in Wisborg? Why does he not try instead to unburden himself of his terrible experiences and worst fears by recounting his adventures to those closest to him?

THE CONFIRMATION PHASE

In the ideal template of Noel Carroll’s ‘complex discovery plot’, this would be the perfect time for the confirmation phase, which ‘involves the discoverers of or the believers in the existence of the monster convincing some other group of the existence of the creature and of the proportions of the mortal danger at hand […].

72 In

Nosferatu the transition into the confirmation stage would appear to be rather smooth, especially considering the fact that Ellen seems to be already strangely abreast of the terrible events that are taking place in Wisborg and of the connection between the mysterious figure looking at her from across the canal and the plague that is decimating the town’s inhabitants thus rendering for Hutter virtually unnecessary the act of convincing other people of the existence of the monster that often takes up a large part of the confirmation stage. However, in Murnau’s film this phase gets strangely frustrated. At no time during the film Hutter conveys his knowledge of the vampire to Ellen – or to any other character for that matter – although we know that after the events, he does recount his story to the film’s narrator. On the contrary, he tries to prevent his wife from reading the

Book of Vampire and he obstinately refuses to acknowledge her awareness of the existence of the monster. The other characters in the story are equally blind or kept away from the truth. Even the Paracelsian Professor Bulwer who seems, or at least should be, in tune with the mysterious forces lurking in nature’s darkest corners fails by the end of the film to make the connection between the plague and

Nosferatu. Thus his narrative function gets completely drained of any possible centrality: if in Stoker’s novel Van Helsing is the real driving force behind the understanding of the events and of the plot that will bring to the final dispatching of the monster, in

Nosferatu Bulwer turns out to be a rather inane and pathetic figure, incapable of leaving any remarkable trace in the story.