Noteworthy Glasshouses

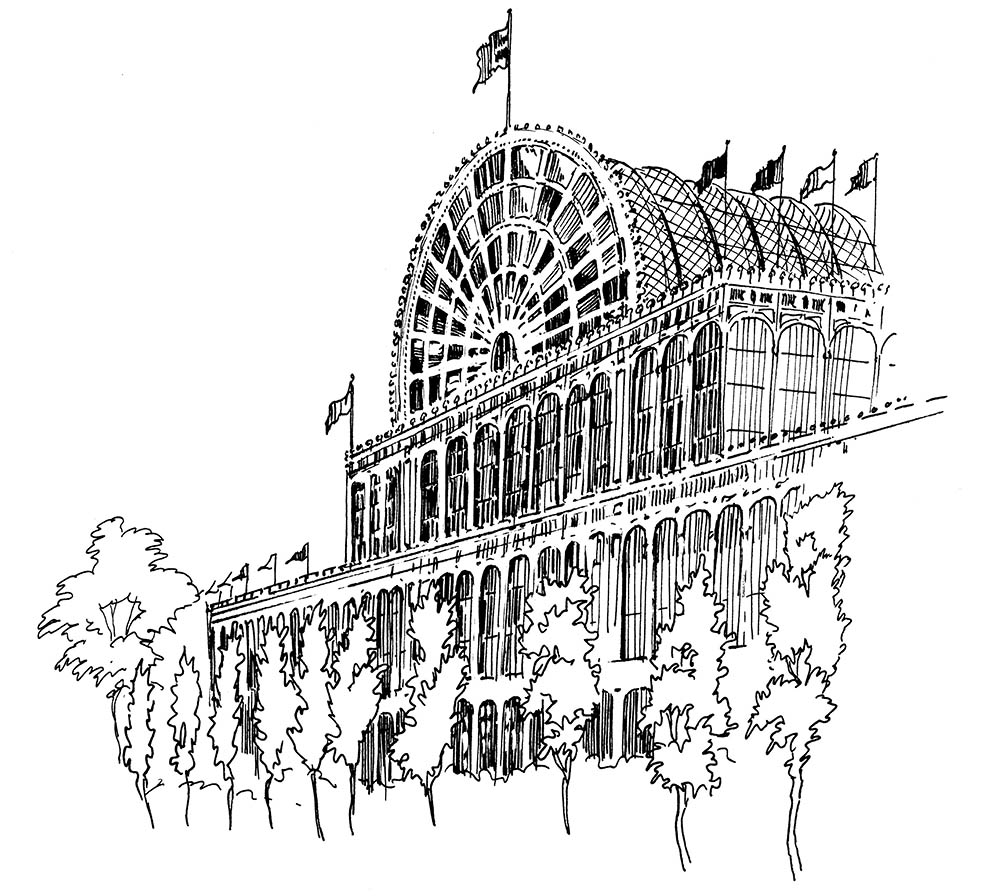

The Crystal Palace in London, built for the 1851 World’s Fair

BEFORE YOU GET TOO DEEPLY INVOLVED in building your own greenhouse, let’s take a brief historical tour of those “glasshouses” that we’ve turned to again and again for both pleasure and purpose.

Of course, greenhouse development could not begin until glass had been discovered. Most experts say that glass was first made about 4000 years ago in or near ancient Persia or Mesopotamia in the Middle East, when people used cooking fires to heat the local sand, melting the silica in it to form glass globules. These globules were then melted into molds and used for arrowheads and knives. Eventually, methods for producing glass improved and it was used to create objects for both practical and decorative purposes.

By 600 b.c.e., glass “recipes” were being recorded, but another 2,000 years passed before glass could be made cheaply enough for use in greenhouses and windows. This, however, did not stop the Roman emperor Tiberius from trying to grow out-of-season cucumbers under cover. Tiberius craved cucumbers all year long and demanded that his gardeners find a way to produce them. The workmen reputedly split off pieces of semitransparent mica and used them against a south-facing wall or in a small bed to cover tender crops in heated cold frames called speculariums. We don’t know for sure whether this method worked, but the concept of growing plants under cover had been born.

It did not catch on quickly, however. The art of gardening under cover was lost for many years until the sixteenth century, when people attempted growing plants under semiopaque oiled paper and canvas and when, in the middle of the century, glass was “reinvented” in Europe. Yet it wasn’t until glass became easier to make and less expensive that it was used for glasshouses, as greenhouses were first called.

Most sources give credit to Jules Charles, a French botanist, for designing the first glasshouse in 1600 or earlier. It was built in Leiden, Holland (perhaps giving an early start to the Dutch greenhouse industry). From that time onward, until the 1690s, affluent people experimented with glasshouses, and many large and very expensive structures were built throughout Britain, France, and Holland.

One of the first recorded conservatories, another name for greenhouses, was the one owned and written of by the Englishman John Evelyn, F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society). Evelyn lived around the same time as the famous diarist Samuel Pepys, and like Pepys and other rich landowners of the day, he kept a diary. While Pepys’s diary dealt with more topical events, Evelyn wrote about the gardens and plants of his time. He also wrote several books, the best known of which is Elysium Britannicum, a huge work that was not finished or published until after he died. He also published a gardener’s almanac and Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets. Evelyn’s conservatory, heated by an enormous woodstove, was used for preserving delicate plants, many of which he had collected on his travels around the European continent during the English Civil War, which started in 1648.

During Evelyn’s time, the use of glass in general slowly became more popular, but most glass could be made only in small panes of varying thicknesses and densities. To make these small panes into something large and more useful, a technique was employed that had been used for the stained-glass windows in many churches constructed in the medieval era: They were held together with lead casing.

Around 1700, a few very rich merchants tried growing warm-weather plants under glass in England’s moderate winter climate. The most successful of these designs was the orangery. In most cases, an orangery was built against a brick wall, with a sloping roof and the other three sides constructed of glass. As you might guess, its intended use was to grow citrus fruits. To keep the ground warm in the orangery, the gardeners of the time either built deep garden beds that were partly filled with horse manure and straw and covered with a foot or two of loam in which the trees were grown or placed pots containing the orange trees directly into beds of manure and compost. The decomposition of the manure kept the bed temperature at around 110°F to 140°F, which allowed citrus trees to grow. Moving large orange trees and spreading new compost around the tree roots or pots each fall must have been quite a laborious chore.

The term greenhouse came into use late in the eighteenth century, when growers noted the green appearance of the fruits and vegetables growing in these orangeries in the middle of an English winter.

In the United States, one of the first greenhouses on record was built in 1737 in Boston for Andrew Faneuil. Like his English counterparts, Faneuil wanted to grow fresh fruit in winter — and he was not alone. George Washington is reputed to have grown pineapples at Mt. Vernon so that he could serve them to his dinner guests. His glasshouse used the same manure-heating techniques used in the English orangery, but he called his structure a pinery.

Orangeries and pineries became much more popular after 1850 or so, when glass was first produced in large sheets and became a relatively inexpensive product. At that time, wrought iron, instead of wood, which tended to rot fairly quickly, became the glass (or glazing) support of choice. Eventually, these developments led to the construction of larger and larger greenhouses, which were used mostly to grow fruit out of season. Many of these huge structures were still the province of the very wealthy. By the mid- to late-1800s, however, large display greenhouses became an important trend in botanical science, with greenhouses being erected at many major botanic gardens in both Britain and America.

One of the best known of these large greenhouses was the Crystal Palace, a huge structure built in Hyde Park in London for the 1851 World’s Fair. This building was close to 410 feet wide and 1,850 feet long, covered more than 19 acres, and contained almost a million square feet of glass in its walls and roof. It also had fountains that shot jets of water 250 feet into the air. After the fair, the Crystal Palace was moved to Sydenham Hill in North London. It was finally destroyed by fire in 1936.

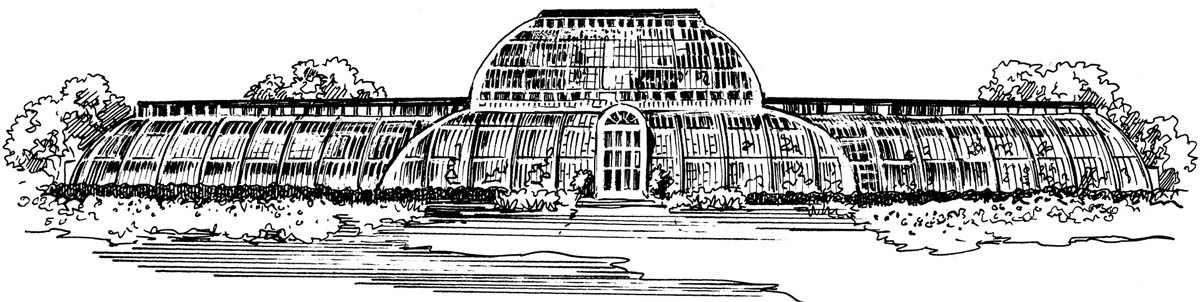

The Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is another glasshouse built to similar mammoth proportions. The building was originally erected in 1848 and was recently restored. The Palm House is 363 feet long, 100 feet wide, and 66 feet high. Currently, its glass is supported by about ten miles of stainless-steel glazing bars, which have replaced the original bars.

England’s early-Victorian-era conservatory craze largely passed by the United States. Shipping embargoes during the Civil War prevented importing these structures, and Americans at this time had more pressing concerns than investing in such an expensive hobby. It wasn’t until the Gilded Age, which began in the late 1860s, that large American greenhouses began to come into their own.

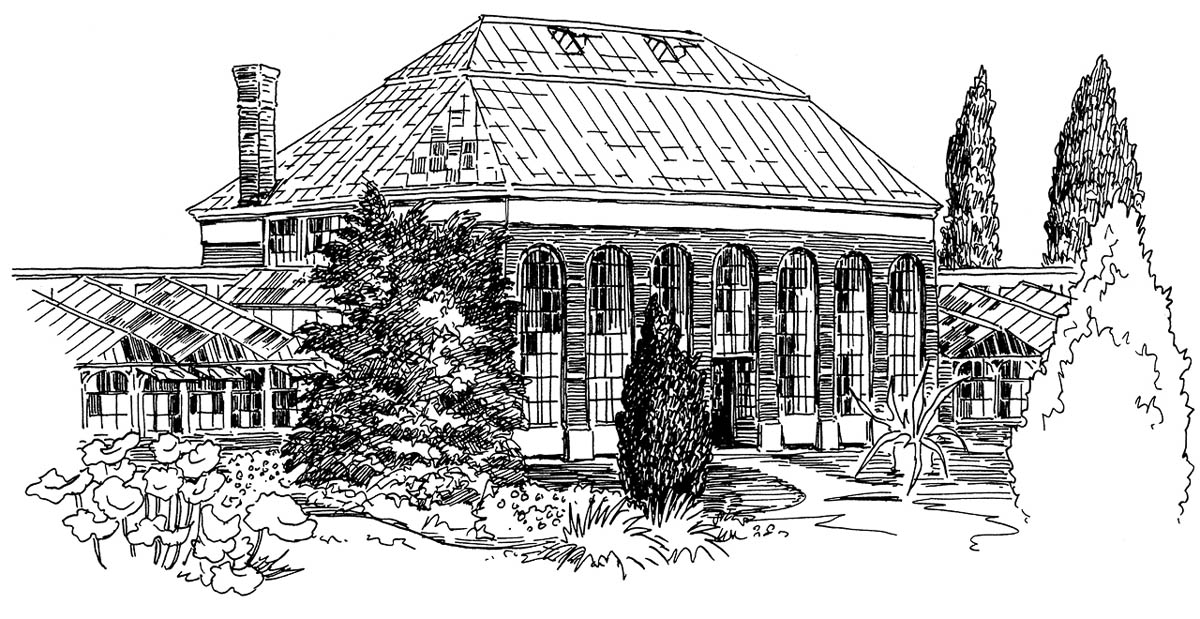

One of the first examples was built by an Englishman named Henry Shaw in what is now the Missouri Botanical Garden. The building, known as the main conservatory or the 1868 House, enclosed exotic plants of many kinds. A few years later, in 1880, Shaw added another greenhouse near the main conservatory. This building became known as the Linnaean House and is still home to palms, citruses, and other tropical and semitropical plants.

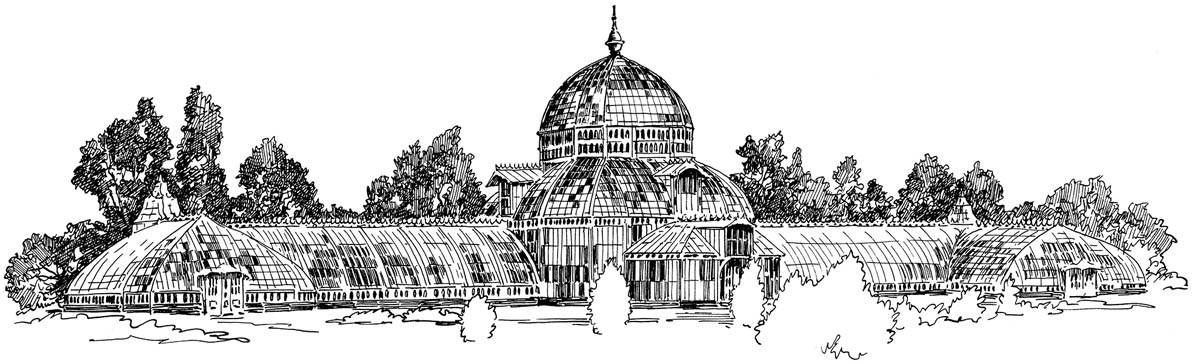

Another beautiful old glasshouse is the 12,000-square-foot Conservatory of Flowers in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. It was erected there in 1879, although most of it was reputed to have been made in Europe and shipped to San Francisco. This conservatory is listed as the oldest wood and glass greenhouse in the United States, with a significant portion of the structure being made of California redwood. It is now on the National Register of Historic Places and has recently been completely restored after high winds, structural damage, and the use of lead-based paints and other unsuitable materials threatened to close it permanently in 1995. Since these earliest American conservatories were built, many others have been constructed, including the Haupt Conservatory in the New York Botanical Garden, built in 1902.

The main conservatory or 1868 House at the Missouri Botanical Garden

The Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was built in 1848.

The Conservatory of Flowers in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park

These botanical garden greenhouses were heated by a combination of methods. One involved using hot beds made from manure and straw piled so that the compost heated up as it rotted. Once these beds were covered with loam, it became possible to grow plants on top of the heated compost. The number of horses in those days made it easy to get manure. Another method involved keeping the air warm with furnace-heated water that circulated through pipes around a greenhouse’s perimeter. (The furnace was invented in England to heat greenhouses long before it was used to heat people’s homes.) In addition, on clear days sunlight contributed to the level of heat in a greenhouse, often necessitating that windows be opened to vent the structure. The combination of these three heating methods allowed the season for citrus fruits and other warm-weather crops to be extended long enough for the fruits to be harvested even in cold climates.

The fresh fruit and flower market that such structures supported rapidly led to the building of commercial greenhouses all over Europe, especially in Britain, Holland, France, and Belgium. These were the days before trucks and planes carried fresh produce to market from far-off regions. Because everything had to be grown in local areas, greenhouses were a boon to growers. By around 1880, tomatoes were being produced in European greenhouses, mostly in France and Holland. The greenhouse industry looked set to thrive and expand.

But in World War I, millions of working men were killed on the western front. Many of these young men came from estates that had invested in the labor-intensive greenhouse market. Without these workers, the industry simply could not maintain its output, and it declined significantly as a result. The business of greenhouse growing did not recover fully until after World War II. In the United States, the Great Depression coupled with the high cost of capital investment required to construct greenhouses kept the greenhouse market from expanding much between the wars.

After World War II, aluminum and galvanized steel came into consistent use for greenhouse framing, eliminating altogether the need for wood, which nowadays is used only in smaller kit or hobby greenhouses. In addition, the use of lighter-weight polycarbonate, acrylic, or polyethylene glazing instead of glass made it relatively inexpensive to erect a greenhouse and easier to control the growing environment. Because of their higher insulation value, these lighter plastic materials also tended to make greenhouses less expensive to heat. As a result of these developments, the commercial greenhouse industry expanded worldwide, especially in Holland, which, with its rich soil and temperate climate, has the largest greenhouse area of any country in the world.

The growth of commercial greenhouses set the stage for a rapid expansion of the use of hobby greenhouses. Plastic and aluminum greenhouses became available to the home gardener for only a few hundred dollars. In addition, many new greenhouse add-ons such as hot tubs, spas, and fishponds, as well as new varieties of plants, also encouraged the growth of home gardening under cover. The result is that today, more and more keen gardeners are buying into the greenhouse lifestyle.

The hobby greenhouse market has been particularly explosive in many European countries. In Britain, for example, it seems that every garden plot has a greenhouse. In the United States the market is gaining momentum, with many people supplementing their gardening pleasure with a small greenhouse. Gardening is currently a very popular hobby in the United States: According to the National Gardening Association, one in four American families claims to have a garden. This can only strengthen the home greenhouse market in the future and help it to grow even more.

A commercial greenhouse