CHAPTER TWO

THE MORSE MASTERMINDS

For many decades, they were Bletchley Park’s forgotten secret agents: thousands of young women and men, sitting in wooden (or bamboo) huts, in all manner of terrain from Cornwall to Cairo to Colombo, working around the clock to intercept all enemy radio messages—encrypted messages transmitted in Morse. This extraordinary global operation sent invaluable material back to the codebreakers, for the analysis that would enable them to see deep into battlefield plans and strategies.

The aim of the puzzles in this section is to give a flavour of the gruelling recruitment and training tests these young people faced. And also to give a sense of the unique toughness of this still largely unsung role: a glimpse into the mental agility of the secret listeners.

Some of these dedicated operatives would be listening in to pilots flying over the Channel; others would be carefully monitoring communications being sent around the Mediterranean. This was the raw material that was being fed back all day and all night to the cryptanalysts, and all of Bletchley’s out-stations dotted around the country.

These recruits were working for the “Y Service,” the Y standing for “wireless.” Like their codebreaking colleagues at Bletchley, they had all signed the Official Secrets Act; like those colleagues, they assumed that the penalty for giving away those secrets would be death. Their role was every bit as mind-wracking and pressurised as the work going on in the Bletchley huts. Most of their roles revolved around Morse: the dot-dot-dash code in which radio messages were transmitted. Very simply, sitting at their radio sets, they had to track down enemy transmissions, and then—with unerring accuracy and at extraordinary speed—transcribe and translate the Morse that was pouring through their headphones.

The ability to translate Morse accurately at speed was a skill learned with difficulty, one that required young, eager, elastic brains. To see and hear the dots and dashes, delivered incredibly quickly, and to instantly visualise the letters of the alphabet they signified, needed furious dedication and focus.

Like their Bletchley-based colleagues, the women and men of the Y Service arrived there having had their intelligence noted in aptitude tests. Pat Sinclair was a teenager from north London. In 1940, from the heights of her hilly suburb, she had seen first-hand the horror of the Blitz. This made her utterly determined to sign up to do her bit.

While working for the local electricity board, Pat taught herself Morse code, with the help of a radio enthusiast friend. Her aim was to get into the Wrens—firstly because she was attracted to the possibility of this sort of intelligence work, and secondly because she regarded it as the most glamorous of the services.

Her gambit worked: she told the recruiters she could manage five words a minute in Morse so she was duly packed off to a camp in the suburb of Mill Hill to take a wireless telegraphy course. She was swiftly to discover that the intensity of the work could create casualties.

This was also found by fellow young Londoner Bob Roberts, from Islington, who had gravitated towards this branch of code-work because of his overwhelming love and obsession for the technology of radio. He was sent to Skegness for training; like Pat Sinclair, he quickly discovered what was required. These Y Service whizz-kids—soon to prove completely invaluable to the Bletchley operation—would be asked to reel off twenty to thirty words a minute from Morse; this was a breathtaking proposition, requiring superhuman speed of thought and reaction.

Clearly not everyone could do it. Bob Roberts remembered how even in the early stages of training, the pressure became too much for some recruits, who were forced to withdraw after suffering mini-breakdowns. Adding to the difficulty was the knowledge that total accuracy was required; anything less and lives on the battlefield would be lost.

More pressure was to come. While some recruits would be based in stations dotted around Britain—from the wilds of Wick in Scotland to huts not far from the white cliffs of Dover—many other young women and men would find themselves boarding ships to destinations unknown.

Some Wrens found themselves posted to Egypt—a Bletchley codebreaking outpost in Cairo—working amid vivid colours, intoxicating scents and all-pervasive sand. Others were dispatched further yet, to Colombo in Ceylon, where they would find themselves intercepting Japanese coded messages in huts with ceiling fans and regular invasions from snakes and insects.

Among the men, Bob Roberts was posted to Alexandria, Egypt, faced with a new world of heat, blinding sun on white dunes, and flies. He secretly intercepted enemy messages through the night: sometimes there were desert thunderstorms which—if you did not grab the headphones off fast enough—could cause permanent hearing problems as the roar of the thunder came shooting down the wires.

Then there was Peter Budd, a teenager from Bristol, who found himself on the other side of the world in an unspoiled paradise: a secret listener in the Cocos Islands deep in the Indian Ocean. To counter the pressure and intensity of the work monitoring Japanese vessels and aeroplanes, he and his colleagues were lucky enough to find themselves in a rich realm of emerald foliage and pale blue waters, with plentiful supplies of fruit, beer and gramophone records.

The linking factor between all these men and women was the amazing elasticity of their brains. Not only did they relish puzzles, but they also had the capacity to work at high speed: not merely instantly translating Morse but also dealing with the multiple distractions—fuzzy frequencies, competing voices—that could potentially cause confusion.

It also became clear that age was a crucial factor. Secret listeners over the age of thirty would often find the work trickier; indeed, the stress led to some being taken away for medical attention.

It was a while before Wren Anne Glyn-Jones—training in rural Devon in 1942—was let in on the secret of why she was being drilled in Morse to this level of intensity. But she soon found herself being posted to Gibraltar, a particular hotspot during the war, as well as a crucial Bletchley/Y Service out-station. She wrote: “Every day we ditted and dahed. Visualising Morse as a series of dots and dashes was rapidly eliminated from our minds; speed depended on our capacity to achieve a completely automatic connection between what we heard and what we wrote down.

“The connection between ear and hand had become so automatic that we ceased to use the conscious part of our minds,” she added. “I remember a moment of panic when I completely forgot what the symbol ‘dit-dah’ meant, and while I struggled to remember, I watched with interest as my own hand reacted to the stimulus by writing—quite correctly—the letter ‘A.’”

Morse now is almost extinct: it was killed off by the advent of the digital age. (That said, there are sailors and pilots who still sensibly take the precaution of learning it in case of general computer breakdown.) By and large it is difficult now to imagine just how skilled the secret listeners were. They not only became proficient in a language that appeared to the uninitiated as merely a series of beeps, but in a curious way they also got to know the various enemy Morse operators who were sending the messages.

The secret listeners came to recognise what they called “fists”; that is, the operating style of those who were sending the messages. Many said that somehow, they came to know a little of their counterparts’ personalities as a result.

Ray Fawcett was one such secret listener who recalled that there was almost a curious intimacy between the interceptors and the people sending the messages out. Those Germans knew that their communications were being harvested—because they were of course in turn harvesting British messages.

Even more directly, there were Wrens engaged in interception on the south coast of England—installed in little wooden huts, exposed to German fighter fire while listening to the messages passing between the Luftwaffe pilots.

The pilots knew that young women were eavesdropping on them; sometimes they called out jokey, suggestive phrases in English to let the Wrens know. Some Wren veterans later said that they came to feel a little fond of these young German men, and always felt curiously stricken when they were shot out of the sky by defending British pilots.

At the core of all this was the fact that Y Service operatives prided themselves on a certain mental agility. For Pat Sinclair, learning this new technical skill was, she recalled, a little like shorthand, only much more complex and with rather graver consequences if any mistakes were made. Based in the Nissen huts at HMS Flowerdown, near Winchester, Hampshire, she worked exhausting shifts deep into the night, supervisors taking all the Morse that she had transcribed on special sheets, and sending these letters off for decryption at Bletchley Park.

And for these women and men alike, there was curiosity too about the science of radio transmission: the way that signals would bounce off the ionosphere, the means by which one could focus one’s interceptions on enemies many miles away. As a result, these operatives were perhaps slightly more practical-minded than some of the boffins at Bletchley Park; these were people who could disassemble and reconstruct complex radio sets without a second thought. The training they received was also about developing a certain level of mental toughness. The tests they faced almost turned their brains into computers.

The time element was obviously vital too: in the flames of battle, when orders and messages were flying to and fro with lightning speed, the secret interceptors had to be focused to an almost preternatural degree. Imagine then that pressure when one was stationed deep in the heart of a sweltering jungle, or (as in the case of Bob Roberts in a later posting) high up in a mountain hut in the dead of night in southern Italy—with the place suddenly surrounded by hungry mountain dogs.

The puzzles in this section are in part intended as a tribute to these neglected listeners: a series of Morse messages, with keys, but with the proviso that the messages must be translated and decoded against increasingly tight time limits. Though it is obviously impossible to replicate the searing pressure that the secret operatives worked under, the puzzles might just give an insight into the sort of challenges they would have faced.

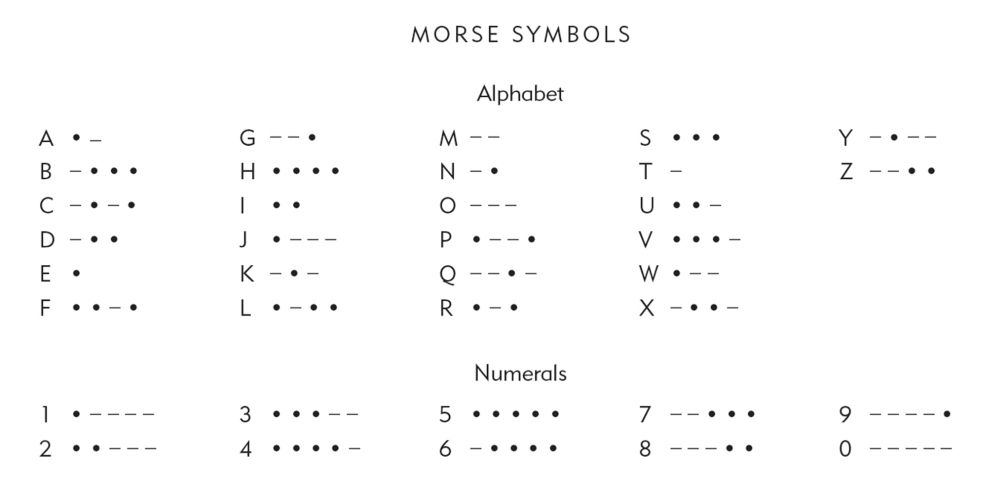

For some of these puzzles, you will need to know the Morse symbols, as found in the following table:

MORSE SYMBOLS

Alphabet

1

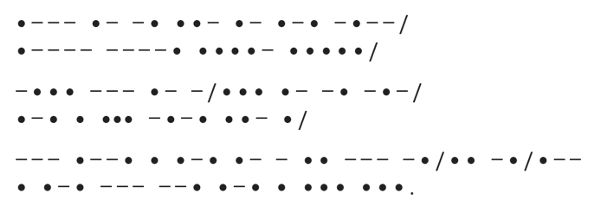

THE FIRST MORSE MESSAGE

On May 24, 1844, almost a hundred years before World War II, Samuel Morse sent his first Morse code message using a dot and dash code, between Washington and Baltimore. It was sent by means of sound down a telegraph wire and his very first message was: “WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT.”

Decipher the message below which uses the same letters as Morse did all those years ago in that original communication—but not in the same order! A / signals the end of a word. You have 5 minutes to complete this assignment.

2

DISASTER TRANSMISSION

A message received at Bletchley towards the end of World War II. Can you decipher the message, including the month of its transmission? You have 6 minutes to finish.

3

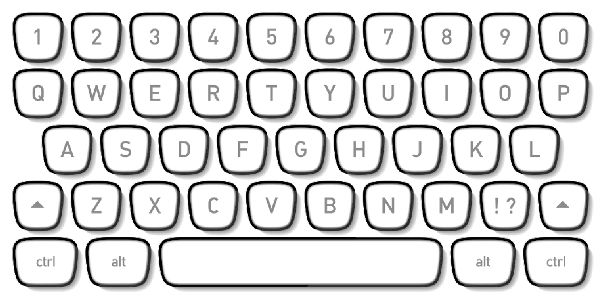

KEYBOARD CRISIS

A Morse code message has been decoded by the boffins across the Park and the message must go now! Unfortunately the typewriter has seized up and only the top line of the qwerty typewriter is functional. So for example, the number 6 could be a Y, an H or an N. Remember also a number might be just that—a number.

By pressing the number keys a choice of letters is possible but with speed, accuracy and logical deduction can you work out the correct message?

- a) 8 7 7 8 6 3 6 5 / 3 3 0 1 4 5 7 4 3 / 5 3 / 0 4 3 0 1 4 3 3 / 5 9 / 1 7 8 5 / 2 1 4 3 / 6 9 7 2 3 / 2 8 5 6 9 7 5 / 3 3 9 1 6.

But it’s not always bad news . . .

- b) 0 3 6 3 9 9 0 3 / 1 4 4 8 4 3 2 / 0 9 4 5 2 7 9 7 5 6 / 4 0 7!

4

OVER TO YOU

Try your hand at translating this message into Morse code. It is taken from an authentic message transmitted in 1944. You have 6 minutes to complete the translation accurately.

ARROMANCHES UNDER FIRE. REINFORCED AIR RECCE. JUNE 6 NORMANDY.

5

HEARTBEAT

- a) Julius Caesar recorded the square root of 25, and linked it via Morse code to a piece of classical music.

- b) The recording of two vowels might tell you to “put that light out,” however old you were.

- c) And why might 9T make everyone stand up?

6

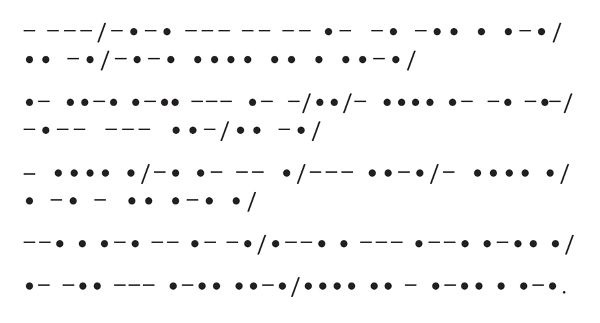

MORALE BOOSTER

A message from May 1941, intercepted by Bletchley, highlighting the need to keep the propaganda war alive. You have 9 minutes to decipher the message.

7

DASH IT ALL, DOT!

What is the link in the listed words below?

- a) T E E

- b) M A I N

- c) W O R K S

- d) F L Y

- e) And if you’ve dashed off the solutions to those, what about S H E and T O M?

8

UNDER PRESSURE

Over to you again to send out the message. Lives depend on it. Speed and accuracy are of the essence. You have 5 minutes from the time you start. You should be getting quicker at this now so the time allotted per word is getting shorter!

FROM U1103 EISELE TO CAPTAIN U BOAT BALTIC. TUBE NUMBER 4 LEAKING, FLOODING AND DRAINING.

9

BLITZ

Each numbered line of Morse code letters can be split into two names of places of the same length when decoded. Unfortunately the lines have been scrambled but the names still read from left to right, and are in the correct sequence. Translate the Morse code and work out the names in question. You have 12 minutes to complete this task.

10

SWITCHBOARD

Everyone played their part at Bletchley Park. Telephone systems relied on alert operators being able to make sure that all communications were properly routed.

Starting with the letter given in the bottom left-hand corner of the grid opposite, make the connections to link all the listed words back up the grid to form a chain in which words overlap (words may read backwards or forwards depending on the direction of the arrows). The last letter of each word is also the first of the next. When a word finishes in a numbered square move straight to the other square in the grid that contains the same number. Repeat the last letter, then continue. Take care! There are many permutations but only one complete answer.

|

ARMADA |

CIRCUS |

DIRECT |

DYNAMO |

ENDING |

FINISH |

GALLOP |

|

HALVES |

KNIGHT |

LINTEL |

LIQUID |

MOSAIC |

NEBULA |

NORMAL |

|

OPTION |

POTION |

RECTOR |

RETORT |

SQUEAK |

SYSTEM |

TARIFF |

|

TEAPOT |

TEMPLE |

TORRID |

TURRET |

YONDER |