CHAPTER FIVE

THE CHESSBOARD WAR

Here are the words of a man who—arguably—steered Britain safely through the worst of the Battle of the Atlantic: “My experience,” wrote Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander, “is that it is very difficult to lose at chess with good grace.

“This is because chess being entirely a game of skill,” he continued, “you cannot soothe your wounded vanity by thinking that the cards were against you, that you find grass so slow after hard courts, that the sun was in your eyes when you missed the catch—there are no extraneous influences on which your defeat can be blamed; you are the sole cause of your own downfall.”

He wrote this in one of his several books devoted to the art of chess. And of course, for chess, read codebreaking, for what Hugh Alexander carefully didn’t mention in any of his books on how to play the game was that he was one of Bletchley Park’s brightest stars.

He was also careful not to mention the fact that several other brilliant tournament chess players in Britain at that time had also worked at Bletchley Park. The game was practically the spine of the institution. To reflect this, the puzzles in this section will have a chess theme, including problems set by Alexander himself and a handy primer for those who are not hugely familiar with the game.

Strikingly, the talent-spotters for the wartime codebreaking centre knew very early on that they had to scout out the world of chess.

As George Atkinson wrote in his book Chess and Machine Intuition: “(Director Alastair) Denniston understood that chess players tend to make good cryptographers . . . both activities depend on trained intuition, the ability to recognise patterns within specific contexts.”

It was perhaps little wonder that the Bletchley department called the “Government Code and Cypher School”—forming the acronym GC&CS—was affectionately nicknamed the “Golf, Cheese and Chess Society.”

Of those chess masterminds scooped up for the Second World War, Hugh Alexander had been a junior champion in his youth, as had Stuart Milner-Barry and Harry Golombek. And of course the entire reason for their suitability can be found in that paragraph of Alexander’s above: when faced with Enigma and other German encoded variations, the cryptanalysts had to bring not merely intellect alone, but also aggression, guile, a certain devilish glee and a fierce competitiveness.

Stuart Milner-Barry had, like Hugh Alexander, been a “Boy Champion” at chess in the 1920s and the two got to know each other in university. Indeed, when war broke out on September 3, 1939, the pair of them were actually at an international chess tournament in Argentina; they immediately abandoned it to sail back to Britain on an eerily deserted cruise ship. Very shortly afterwards, they answered the call from Bletchley.

Milner-Barry later confessed that, although one should never really say this about war, he and Alexander had an exhilarating and comfortable time. The codebreaking problems really were like chess. Milner-Barry said: “Both for Hugh and myself it was rather like playing a tournament game for five and a half years.”

As Hugh Alexander succeeded Alan Turing to become head of Hut 8—dealing with naval Enigma codes—Milner-Barry was head of Hut 6, dealing with army and air force ciphers. They had both previously learned a valuable principle in their world of competitive chess: how to make light of the most intense pressure, while simultaneously using that pressure as a means of kick-starting the mind.

The ability to visualise as-yet-unmade chess moves; the ability to foresee the likely moves that your opponent might make; the ability to spot a potential solution to a seemingly insoluble problem—these were all weapons in the chess player’s armoury.

Strikingly, given that he was by some distance Bletchley’s most original thinker, Alan Turing was not especially good at chess. His colleague Peter Twinn recalled how sometimes, after shifts, they would go back to Twinn’s digs in town and play. Twinn—who was only the most casual player of the game himself—frequently won.

Nonetheless, the game did have a powerful hold on Turing’s imagination in another sense: shortly after the war, as he was working to bring his dream of a thinking machine into reality, Turing devised a then extraordinary computer program that would enable such a machine to play chess. The project was called Turo-Champ. These days the idea seems commonplace: before 1950, it was science fictional.

Turing also had competition from some other former codebreaking colleagues, who after the war had returned to academic careers in Oxford. Shaun Wylie—who was to be yanked back into the secret world by being offered the position of head of mathematics at the new GCHQ in the 1950s—was working on his own computer chess program together with another Bletchley veteran Donald Michie.

Their chess-playing computer project was called Machiavelli. And primitive though their machinery was—computers then were the size of cupboards, and could fill entire rooms, the labyrinths of their wiring trailing everywhere—the intellectual ambition was dazzling. Even to have come up with a machine that could “think” one move ahead was an extraordinary achievement.

Wylie and Turing were rather tickled by the possibilities of their programs and had the idea that their rival computers could face each other in a chess challenge. How would machine play machine? Would that produce any evidence that these masses of circuits could in any possible sense “think” a problem through?

Through correspondence, the two men set up the game and indeed their machines did come up with moves. The only difficulty was the time spent setting them up in order to do so; in an age when electronic miracles are performed on our phones in the blink of an eye, it is difficult to conceive of a time when computers were hot, noisy contraptions that smelled of oil and heated thermionic valves and when programming was a serious time-consuming endeavour. One chess move could take weeks, even months. After cajoling a few moves out of Turo-Champ, it was Turing who gave up the battle first, discouraged by the length of time it took.

Machines aside, Turing also happened to enjoy the game as a means of relaxation, while others seemed to enjoy taking him on for the challenge of pitting their intellects against his exceptional genius. At Bletchley, Turing was challenged to a match by one of the Park’s most formidable champions. South London-born Harry Golombek had, before the war, become established as one of the world’s brightest talents in the game, so his recruitment into the world of ciphers was a natural move. Golombek went a little easy on Turing during their matches across the board, but even so, Turing was never up to it.

A beguiling thing about these chess-players was that they came from a variety of backgrounds. Golombek’s parents were Russian Jewish, having established themselves as grocers in south London at the turn of the century. Milner-Barry and Alexander came from middle-class, middle-England backgrounds. Yet before, during and many years after the war, they all remained extremely close-knit.

While the codebreaking that went on at Bletchley Park obviously remained a deep secret, it happened to be a secret that was known by Ian Fleming. The creator of James Bond, who had worked in naval intelligence throughout the war, was one of the tiny handful of people outside of Bletchley Park who was allowed in on the codebreaking efforts. Fleming was fascinated by the link between chess and codes, and in 1953, he was beguiled by the sensation caused at the Hastings International Tournament.

That year was the first that the Soviet grandmasters David Bronstein and Alexander Tolush came to Britain to play. And they found themselves up against the amused—and amusing—figure of Hugh Alexander.

The newspapers—with absolutely no idea of Alexander’s top-secret shadow career breaking into Russian codes—reported on his matches with these chess titans breathlessly. And when he beat them both, Hugh Alexander became something of a modest national sensation.

It seems quite clear that Fleming lodged the match away in his creative imagination, for in his 1957 Bond novel From Russia With Love, there is a scene involving a Soviet chess champion cryptologist struggling to focus on a tense tournament match while being summonsed by the KGB villain Rosa Klebb. The real-life struggle between Alexander and the Soviets—a Cold War battle being fought across a chessboard—had clearly been the inspiration.

The apparent insouciance of Hugh Alexander—a trait he shared with other chess-players—was in its own way a means of holding on to sanity during wartime. Life in Hut 8 might otherwise have simply been too much: when German U-boats were sending precious lives and cargos to the bottom of the sea, Alexander and his team were under constant pressure from Downing Street to crack those U-boat codes and get fixes on their positions and courses.

The ability to play chess also relied on the ability to flick a mental switch. The problem in hand would receive full focus, but when off-shift, it was important to be able to shut it out. All-important was the capacity to relax and laugh. Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry had a bit of a head start with this as they were billeted in one of Bletchley’s most agreeable old pubs: the Shoulder of Mutton. Here they could relish the good local beer and the landlady’s apparently very fine cooking.

In the later years of the war, another chess enthusiast, Donald Michie (who had been born in Rangoon and who came to the Park after showing a dazzling capacity for learning Japanese at speed), was working on the Colossus. This was the code-crunching machine that in essence kick-started the computer revolution. Chess was more than just a game to him: like his colleagues, Michie spent a huge amount of time brooding about the possibilities that a chess-playing computer might offer. It wasn’t just about mechanical tactics or stratagems; it was about where such a leap might lead next. Some years after the war, Michie became renowned as a highly distinguished scientist: he and his wife were instrumental in pioneering the ideas and techniques of in vitro fertilisation.

An enthusiasm for chess was not confined to Bletchley’s male codebreakers. Another addict was Hut 8’s Joan Clarke, who would later become Alan Turing’s fiancée for a short time. As well as being a genuine passion, a little friendly competition over the chessboard might also have been a means of Joan asserting her status as an intellectual equal among the men.

Chessboards were to be found in the main house, and in Hut 2, which had been set aside for recreation and beer-drinking. Indeed, it was through chess that Joan Clarke got to know Alan Turing better, their relationship in the truest sense a meeting of minds.

In the later years of the war, Bletchley Park’s chess club was, ironically, the most distinguished in the country. Ironic, because none of the club’s opponents were ever allowed to know exactly how these brilliant players were spending their war. In December 1944, the BP Chess Club was looking for fresh challenges and so took on the team at Oxford University. Naturally the Bletchley chess club triumphed. Given the top-secret status of the Park there must have been some bewilderment at this victory among the Oxford dons. In particular, as noted by author Christopher Grey, they must have wondered how it was that a small Buckinghamshire town known chiefly for its brick-making industry happened to be harbouring an extraordinary community of chess geniuses.

The puzzles that follow—while clearly not at the Grandmaster level, since that would hardly be fair—are ticklish enough to give an insight into tactics, strategy, and indeed the aggressive slyness of the codebreakers. Chess and cryptology alike were games that they could not bear to lose.

If you have never played chess before, you can still tackle all the puzzles in this section. If you are more than a little rusty on the intricacies of the moves of individual pieces or you think the Sicilian Defence is an exotic cocktail, don’t worry! All the information is provided in these pages for puzzle solving.

1

OPENING GAMBIT

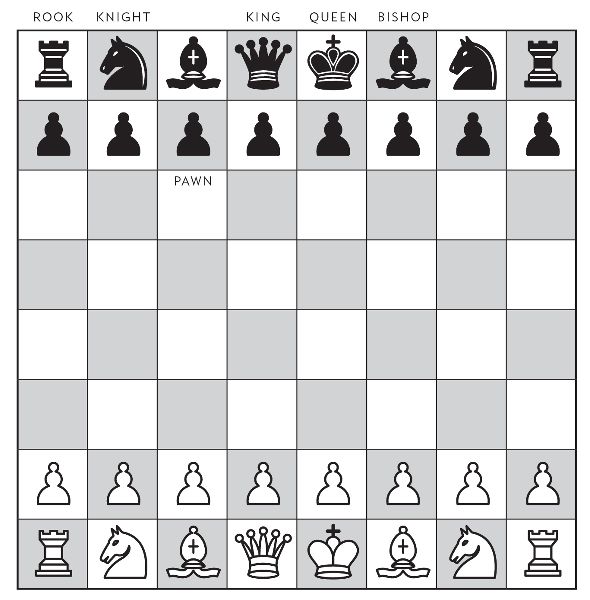

Here’s a chessboard set out for the opening of a game. Each player starts with eight pawns, one king, one queen, two rooks (or castles), two knights and two bishops.

Now here’s a chessboard mid-game, where the remaining pieces are replaced by Xs. With the help of the clues, put all the pieces back in place and pinpoint the position of the two kings.

CLUES

- • White has lost three times as many pawns as black.

- • Overall black has lost more pieces than white.

- • Both black and white have five pieces that have not moved in the game.

- • Both kings and queens are on the board, they have all moved and none are on a square matching their colour. In fact, all of the black pieces are on white squares.

- • Looking across a row, or rank, of squares the two queens have each other in their sights.

- • Pawns like to move forward (they’re the only pieces that cannot move backward) and two pawns are the most advanced pieces down the board for black.

- • The only knights remaining are two white knights, and one is the most advanced piece for white. Both knights are on black squares and they are the only coloured pair of starter pieces that remain on the board.

- • Looking up and down the columns, or files, of squares there are seven times when two pieces with the same name appear in a file together.

2

EXCHANGES

Change one word into another, moving a letter at a time. Below are clues to the words you need, but they are in no particular order AND there is a word included which won’t fit in anywhere. What is it?

Here are the clues to the words you need plus one more:

- Aperture

- Assignations

- Challenges

- Mends

- Metal

- Moan

- Salad ingredient

- Pigs

- Make sense

- Crows

- Young hen

- Travels

- Ships

- Adores

- Unruly children

- Sunrises

- Insensitive

- Small pigeons

- Chatter

- Animal backbone

3

MIDDLE GAME—KING’S GAMBIT

The historic English village of Much-Cheating is home to a prestigious chess tournament. The event attracts interest from abroad, and it is suspected that one of the players may be using the meeting to pass on confidential information. The person playing white thinks he knows the name of the informer. He doesn’t write down the actual name, but he has left a trail to find it from a sketch entitled KING’S GAMBIT.

What is the name of the informer?

4

KNIGHT MOVES

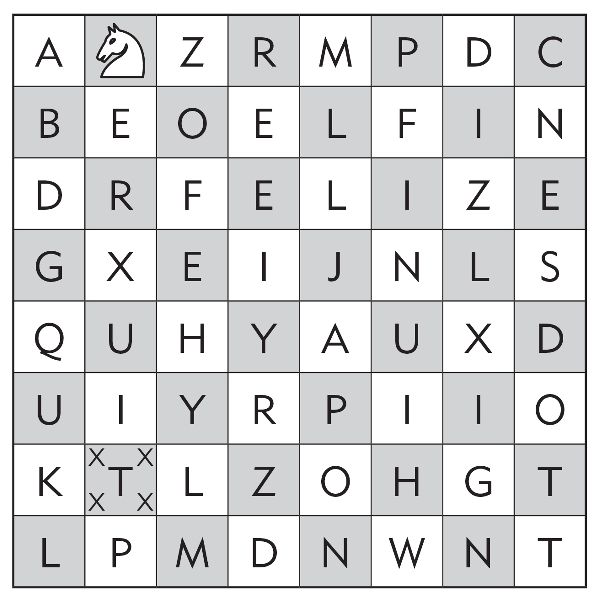

A knight moves three squares in the shape of an L, either one square up or down and two across, or two squares up or down and one across. Moving round this board can you collect the letters on the way and read the message issued by the British government in 1939? Each letter can only be used once but not all letters will be used. The final letter is marked by the Xs.

5

ENDGAME

The words in the “Endgame” column below are each the end of a chain of three words. Each word links to a word in the middle column, and although you can’t see these words they will be in alphabetical order when you have worked them all out. You then have to find a chess-linked answer for the first column that links with the middle column. Fiendish!

| WORDS USED IN CHESS | LINK WORD | ENDGAME |

|---|---|---|

|

CARD |

||

|

ROADS |

||

|

HALL |

||

|

POST |

||

|

WINK |

||

|

CIRCLE |

||

|

TICKET |

||

|

DUTY |

||

|

KEEPER |

||

|

PLUM |