CHAPTER TEN

CODEBREAKERS THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS

The creator of Alice in Wonderland was not just an expert in poetic nonsense; Lewis Carroll (or Charles Dodgson, to use his real name) was also an Oxford mathematician with a taste for symbolic logic and a distaste, in the sunset of the Victorian era, for new-fangled maths theories and practices. Carroll was a great favourite among the codebreakers of Bletchley Park because he used fanciful and comic means of addressing the skill of lateral thinking.

He was a direct influence on Dilly Knox; famously, Knox challenged new recruit Mavis Lever with the apparently simple question, “Which direction do the hands of a clock go round?” The answer can either be clockwise or anti-clockwise, depending on which side of the clock-face one is standing. The codebreakers could not simply rely on the hard certainties of maths. They had to be inventive about which directions they approached these problems from: back to front if need be.

And so the puzzles in this section have a more fantastical quality. They are drawn directly from Lewis Carroll himself: brainteasers that he had published in magazines and periodicals, each delighting in logical and mathematical riddles that are suffused with inventiveness. These were the very puzzles on which so many of Britain’s finest codebreaking minds had been brought up.

The Carroll cult can be traced back to the First World War cryptology efforts. In the dusty Whitehall corridors and offices that made up the department known as “Room 40” and “ID25,” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was a frequently referenced text, not just by the young Dilly Knox, but also by Frank Birch (who later helped to form GCHQ) and Bletchley director-to-be Alastair Denniston.

Indeed, it formed the core of a codebreakers’ Christmas play written by Frank Birch—who as well as being an accomplished cryptologist was also an actor who would later go on to star in films opposite George Cole and Sid James.

The “Alice” figure in this play was Dilly Knox’s fiancée Olive Roddam. After walking down Whitehall and picking up a loose sheet of paper featuring a coded message that begins “Ballybunion,” Olive finds herself whooshed into the looking-glass world of Room 40, where Dilly Knox is a distracted figure—“the Dodo”—who uses some very Carrollian absurdist lateral thinking to explain why his spectacles are in his tobacco pouch, and his tobacco is in his sandwich box.

There was an accompanying song: “Peace, Peace, Oh for some Peace!/ Miss Roddam says Knox does not please her/When instead of a mat he makes use of her hat/And knocks out his pipe on the geyser!”

Another British codebreaker lampooned in this play was the man who triumphantly decrypted the Zimmerman Telegram—a 1917 German diplomatic cable to Mexico that in effect pulled the United States into the Great War. With this decryption, Nigel de Grey pulled off a cipher feat that changed the course of history. Nonetheless, the slightly built de Grey was cast as “the Dormouse” and indeed was known by this nickname even up until the 1950s, when he was turning his laser-beam gaze onto the latest Soviet codes.

The codebreakers who were assembled during the First World War tended to be classicists (though Frank Birch was a historian and Nigel de Grey by profession a publisher). They had minds that could range far and wide, however, and it was not only Alice’s adventures that prompted a new way of looking at the world; it was also Carroll’s approach to lateral-thinking logic problems that helped their own thinking along.

There were currents of deep learning in Alice and her seemingly absurd world and the codebreakers certainly sensed that there was much more to the heroine’s adventures than free-range nonsense. Recently, eschewing modern theories to do with psychoanalysis, Melanie Bayley in the New Scientist magazine detected a sly satire on abstract maths itself—an angle that would have had tremendous appeal to the Bletchley codebreakers.

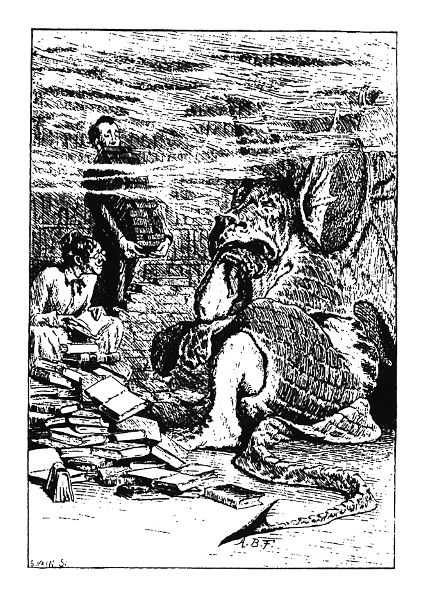

Bayley pointed to the Alice chapter “Advice from a Caterpillar,” where Alice has shrunk and a mushroom seems to provide the chance to restore her. But this restoration proves madly uneven, with Alice gaining an unwanted extra-long neck. Bayley suggested that this was Carroll’s impatience with the growth in abstract maths. His was a world where algebra and its symbols stood for real numbers and real things. But in late nineteenth-century Oxford, this world was increasingly being marginalised; now you could have imaginary numbers—negative numbers—and you could put them into algebraic calculations and produce fascinating results, so long as you followed internal logic.

Bayley argues that Alice partly reflected what Carroll saw as mathematical anarchy: Alice can’t remember her times table, and the Caterpillar seems perfectly relaxed about this and indeed her constantly changing dimensions. This is an absurd world so why should this instability worry him? The same goes for the apparently insoluble Carollian riddle: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?”

For master codebreaker Dilly Knox, there was clearly something hugely liberating in finding the internal logic behind seemingly arbitrary statements and, indeed, arbitrary jumbles of letters. His Lewis Carroll fixation and way of thinking continued at Bletchley and—according to Michael Smith—only the women who worked closely with him at the Cottage in Bletchley Park seemed able to see the clear route of his thinking.

One day Knox mystifyingly declared: “If two cows are crossing the road, there must be a point when there is only one and that is what we must find.” He was referring in an extremely elliptical way to the problem of the Abwehr—or German secret service—Enigma codes. Only Mavis Lever and Phyllida Cross appeared able to follow what he meant. Sadly, his precise meaning has once more fallen into dark obscurity.

Elsewhere, when discussing the moving rotor wheels of the Abwehr Enigma machine, which carried the encoding letters, Knox had observed how sometimes two rotors turned simultaneously and other times all four turned simultaneously. These phenomena he termed Crabs and Lobsters. Crabs were apparently of little use to him. Yet lobsters were.

In another codebreaking method, Mavis and Phyllis were trained to be on the lookout for “Females” (that is, particular alignments on the hole-punched code-unravelling sheets of card). As with all the other colourful terminology, they were unfazed; indeed, Mavis Lever took pleasure in recounting and explaining Knox’s foibles when at last the curtain of secrecy was lifted from Bletchley in the 1980s and 90s.

Funnily enough, Mavis Lever’s talent for looking at problems from Carollian angles had been noted before Bletchley Park when she had been working at the Ministry of Economic Warfare. There was a Morse code transcript that referred to a place called “St. Goch.” No such place exists and the meaning of the message could not be fathomed. Miss Lever saw the letters in quite a different way, however; she perceived that the message was referring to Santiago, Chile—“Stgo Ch.” That was the moment, according to David Lambert (a later academic colleague of hers) when the move to Bletchley Park became a certainty.

Lewis Carroll continued to have a bearing on Mavis Lever’s life after she became Mrs. Batey and later became a landscape historian. Her mathematician husband Keith took on a senior financial role at Oxford University and while they were there, Mrs. Batey was able to explore and write about some of the gardens that had inspired the landscapes of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A few years later, this now prolific author wrote Alice’s Adventures in Oxford, dealing with Charles Dodgson’s time there.

Alice’s creator had some influence over Alan Turing too. A little after the war, Turing organised a treasure hunt for family friends and children. Among the elaborate clues were bottles filled with red liquid (one, “the libation,” smelled terrible, the other, “the potion,” was sweet) and made-up words concealed inside books with fake covers that were hidden on bookshelves.

The offbeat, angled way of looking at things was adopted all over the Park. Bill Tutte’s triumph in breaking into the German “Tunny” codes by hand, using only pencil and paper and two months of deep thought, was one such example, enabling the codebreakers to start reading secret communications straight from Hitler himself.

In the deep winter of 1941, and without even seeing the “Lorenz” code-generating machine that produced the Tunny traffic, Bill Tutte pulled off the unthinkable. Studying the codes, and the patterns that emerged, he painstakingly visualised the sort of technology that would generate them. Using an amazing fusion of intellect and imagination, he summoned a mental picture of the advanced German encoding machine, and looked deep inside it.

And this vision he was then able to communicate to colleagues, in profound detail; it enabled them to build their own new futuristic code-generating—and code-cracking—machinery in response.

In doing so, the engineers also paid tribute to another of Britain’s great masters of the surreal: Heath Robinson. For using Bill Tutte’s deductions about Tunny as a jumping-on point, it was also possible to construct even more advanced technology to start chewing through these fresh ciphers: a special contraption that with its maze of pulleys and tapes and pipes and cables looked like a comic caricature.

It was called the “Heath Robinson” because it resembled one of the preposterously over-complicated creations of this talented humorous illustrator. Heath Robinson’s world, depicted in a huge range of cartoons, involved activities such as serving food, pouring wine—even attempting to silence noisy nocturnal cats—with devices and gizmos that ran on countless wheels and pulleys, sometimes with the addition of balloons.

By contrast, Bletchley’s Heath Robinson was actually built by a brilliant engineer called Tommy Flowers, and the look of it belied its deadly seriousness. This was an advancing world of valve technology, and photo-electric sensors. There was also a great mass of wheels—plus a specially punched continuous paper tape that was the source of equally continuous exasperation when it kept on snapping.

Flowers learned very quickly from all these difficulties, and the technology that he was to dream up in his laboratory afterwards was in quite a different realm. His next creation—the Colossus—was the machine that ushered in the age of programmable computers.

Lewis Carroll himself would doubtless have been thrilled by the influence he had on the formative minds of the codebreakers. In the 1860s, he had devised a few encryption techniques himself, including one that he called the “Telegraph Cipher,” a moderately tricksy variant on letter transposition. It is likely, then, that Carroll would have fancied himself as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park. Certainly, his appetite for puzzles extended, rather like the example of Hugh Foss, to compiling them. In the case of Carroll, he appeared to do this compulsively. He devised cryptograms for Vanity Fair; word progression puzzles (for example, turn “pig” into “sty” one letter at a time in four moves) for other journals including The Lady; and a whole heap of riddles, acrostics, maths teasers and, of course, challenging logic teasers for friends and the wider public alike.

A number of the puzzles in this section were either thought up by Lewis Carroll or were—in their challenge to make you think laterally—inspired by him. These were the sorts of propositions that delighted and beguiled Dilly Knox and Nigel de Grey and a great host of others who came after them.

1

THE CAPTIVE QUEEN

A captive queen and her son and daughter were shut up in the top room of a very high tower. Outside their window was a pulley with a rope round it, and a basket fastened at each end of the rope of equal weight. They managed to escape with the help of this and a weight they found in the room, quite safely. It would have been dangerous for any of them to come down if they weighed more than 15 lbs more than the contents of the lower basket, for they would do so too quick, and they also managed not to weigh less either.

The one basket coming down would naturally of course draw the other up.

How did they do it?

The queen weighed 195 lbs, daughter 165, son 90, and the weight 75.

2

A GEOMETRICAL PARADOX

The four pieces A, B, C and D, which make up the square of area 8 x 8 = 64 square units, is transformed into a rectangle of apparent area 5 x 13 = 65 square units. Where does the extra square unit come from?

3

THE MONKEY AND WEIGHT PROBLEM

A rope is supposed to be hung over a wheel fixed to the roof of a building; at one end of the rope a weight is fixed, which exactly counterbalances a monkey which is hanging on the other end. Suppose that the monkey begins to climb the rope, what will be the result?

Note: the rope is perfectly flexible and the pulley frictionless.

4

CROSSING THE RIVER

Four gentleman and their wives wanted to cross the river in a boat that would not hold more than two at a time.

The conditions were, that no gentleman must leave his wife on the bank unless with only women or by herself, and also that some one must always bring the boat back.

How did they do it?

5

DOUBLETS

Lewis Carroll called these puzzles “doublets.” The aim: transform one word into another. The rules: you can change only one letter at a time. The remaining letters must stay in position and all of the words must be in the dictionary.

To get his readers used to the problem, Carroll set a few “easy” starter puzzles: turn BAT into MAN; TEA into POT; CAR into VAN; and MUM into DAD. Below are a few more that he published in Vanity Fair between 1879 and 1880.

Send JOE to ANN

Change TILES for SLATE

Pluck ACORN from STALK

HOAX a FOOL

Bring JACK to JILL

Serve COFFEE after DINNER

Row BOAT with OARS

Change NOUN to VERB

Bring SHIP into DOCK

PLANT BEANS

Raise UNIT to FOUR

Prove LIES to be TRUE

Turn HORSE out to GRASS

OPEN GATE

CRY OUT

Send BOWLER to WICKET

6

NAMES IN POEMS

The poem below was written by Lewis Carroll accompanying a present of a book called Holiday House, for the three young daughters of Dean Liddell. The poem contains not only the title of Catherine Sinclair’s book but also, hidden within, the names of the three children. Those familiar with the story of Lewis Carroll’s life will have a head start with those names!

Little maidens, when you look

On this little story-book,

Reading with attentive eye

Its enticing history,

Never think that hours of play

Are your only HOLIDAY,

And that in a HOUSE of joy

Lessons serve but to annoy:

If in any HOUSE you find

Children of a gentle mind,

Each the others pleasing ever—

Each the others vexing never—

Daily work and pastime daily

In their order taking gaily—

Then be very sure that they

Have a life of HOLIDAY.

Another poem that Lewis Carroll wrote as a riddle contains the name of another of his young correspondents. At first sight, this problem is slightly more intractable than the last . . .

Beloved Pupil! Tamed by thee,

Addish=, Subtrac=, Multiplica=tion,

Division, Fractions, Rule of Three,

Attest thy deft manipulation!

Then onward! Let the voice of Fame

From Age to Age repeat thy story,

Till thou hast won thyself a name

Exceeding even Euclid’s glory.

7

FEEDING THE CAT

Three sisters at breakfast were feeding the cat,

The first gave it sole—Puss was grateful for that:

The next gave it salmon—which Puss thought a treat:

The third gave it herring—which Puss wouldn’t eat.

(Explain the conduct of the cat.)

8

TWO TUMBLERS

Take two tumblers, one of which contains 50 spoonfuls of pure brandy and the other 50 spoonfuls of pure water. Take from the first of these one spoonful of brandy and transfer it without spilling into the second tumbler and stir it up. Then take a spoonful of the mixture and transfer it back without spilling to the first tumbler.

If you consider the whole transaction, has more brandy been transferred from the first tumbler to the second, or more water from the second to the first?

9

ELIGIBLE APARTMENTS

A tutor and his two scholars, Hugh and Lambert, are looking for lodgings. They come across a square in the town that has four houses displaying cards which say “Eligible Apartments.” However, only single rooms are to be had. There are 20 houses on each side of the square, the doors of which divide the side into 21 equal parts. The houses with the available lodgings are at numbers 9, 25, 52 and 73. The tutor decides to make one of the rooms a “day-room” and take the rest as bedrooms. He sets this problem for his scholars:

“One day-room and three bed-rooms . . . We will take as our day-room the one that gives us the least walking to do to get to it.”

“Must we walk from door to door, and count the steps?” said Lambert.

“No, no! Figure it out, my boys, figure it out!”

Hence, with the provision that it is possible to cross the square directly from door to door, which house will be used for the day-room?

10

WHO’S COMING TO DINNER?

The Governor—of-what-you-may-call-it—wants to give a very small dinner-party, and he means to ask his father’s brother-in-law, his brother’s father-in-law, his father-in-law’s brother, and his brother in-law’s father: and we’re to guess how many guests there will be.

What are the minimum number of guests at the dinner party?