CHAPTER ELEVEN

GOOD, SMART, COMMON SENSE

For the Honourable Sarah Baring, the invitation to work at Bletchley Park had come about partly through opera.

As an upper-class society girl, she had initially found herself working for the war effort making aeroplane parts at the Slough Industrial Estate, the novelty of which had soon worn off. Through family connections, the Honourable Sarah managed to get an interview with the Foreign Office. She was asked if she knew any German and Italian. German wasn’t a problem—she was fluent from time spent there in the 1930s. Italian: what she did know came from La Traviata but she wasn’t going to let that stop her. The bluff worked. She soon found herself on a train from London Euston to the north of Buckinghamshire with a suitcase and a few prized records.

And so the puzzles in this section are to do with the uncelebrated virtues of common sense, allied with quick wits. A great many Bletchley recruits were not remotely academic. Although they had had terrific basic educations, the debutantes and Wrens had very often left school before sixth form.

Perhaps this is why a few of them later referred to Bletchley as “their university.” But even if you weren’t codebreaking, you were still required to work with lightning speed and mental sharpness at all times, and always against the clock.

Some things never change. Alastair Denniston, the director of Bletchley Park, had written himself to the Foreign Office in the early stages of the war. When it came to recruits from both the Wrens and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), he said, he would prefer if they did not send him “too many of the cook and messenger type.” So it was that when women volunteered for the Wrens, there was not only a test but also a questionnaire that probed their interests. The authorities were also asked to be alert for “a high standard of mental agility.”

A great number of the Wrens were destined to work with the bombe machines. While it was not necessary for them to have specifically high skills in advanced mathematical theory, or indeed hugely in-depth knowledge of German or Italian, they were required to be able to respond quickly to exacting circumstances. The machines themselves, while being marvels, were nonetheless very difficult to deal with when they broke down. Wrens were required—even during the 2 a.m. shifts—to be able to fix temperamental bombes with tweezers or indeed anything else that came to hand.

As reported by Christopher Grey in his book Decoding Organization, there was a later survey of the Wrens who had worked on the Colossus machines, which were extraordinarily complex pieces of technology. More Wrens in this area had qualifications—but still a very large number did not. “Twenty-one per cent had Higher Certificate, 9 per cent had been to a university, 22 per cent had had some after-school training, and 28 per cent had had previous paid employment,” wrote Grey. “None had studied mathematics at university.”

It has also been noted by Grey that many of the young women siphoned through to Bletchley had had unusually superior primary and secondary educations, and came from solidly middle-class backgrounds (the same tended to be true of the WAAFs from the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, whereas the ATS attracted more women from a working-class and less educationally privileged background).

Wren Ruth Bourne—a young woman from Birmingham who had devoured spy thrillers in her youth and so guessed very quickly what the establishment of Bletchley was for—had had further education in Switzerland. Barbara Moor had attended grammar school and then went to college thereafter. Jean Valentine, meanwhile, had been taught at Perth Academy, a school with a towering reputation (indeed, the Scottish state education system generally was for many decades one of the great wonders of the world). The daughter of a prominent local Perth businessman, Jean left school at sixteen, which was perfectly common for women at the time. But the school had already given her an all-round grounding that might be comparable to A-level or even first-year degree level today.

Another Bletchley veteran, Jean Millar, talking as part of a special GCHQ event to celebrate women’s history, recalled that she had just taken her solicitor’s intermediate exam in 1943 when she volunteered for the Wrens. She found herself posted to the out-station Eastcote, which is in the north-west of London. Here was an array of bombe machines, divided into bays, each bay dedicated to an Allied country. Round the clock, the machines crunched through codes that had been intercepted and sent from all over the world.

The challenge here for Jean Millar was to apply her intelligence to something wholly, completely new. This was no time for abstractions; instead, she and her fellow Wrens had to be intensely practical as well as nimble-witted.

She remembered that in-depth technological expertise was not necessary; in the case of machines breaking down completely, there were special teams of engineers from the British Tabulating Machine Company. That said, however, it was the job of the Wrens, working with fine brushes, to make sure that the rotating drums and other features were maintained in good order and that the machines kept moving.

Others remembered that the strain of tending to the bombes—combined with the incessant “tickety-clicking” noise and the very fine, almost invisible mists and sprays of oil that they generated—could sometimes get too much. The knowledge of the importance of the work, together with the almost hallucinatory monotony, induced occasional breakdowns.

And the cure for a breakdown? One young woman was prescribed a couple of days in bed, with a jug of water. Anne Hamilton-Grace took this one stage further, replacing the water with a jug of orange juice and gin. However, the point was that there was sympathy and concern: the Bletchley authorities were keenly aware of how debilitating the work could be.

And they were careful about the welfare of the Wrens. Given the intense secrecy of the work, it was in Bletchley’s interests to ensure that they were not forced to crash out of the secret war.

There were isolated cases of accidental disclosure: a former Wren who went on to work in London let slip about some of the machinery that she had been working with. What was remarkable was that Bletchley’s security precautions—the said young woman was contacted and reminded sternly of the Official Secrets Act—stretched out so far from the Park itself.

Despite the grinding nature of the work, what these Wrens needed above all was the ability to extemporise. This was perhaps more on display with the operation of the Colossus machines at Bletchley. With the innovative use of valves, these computers were fearsomely complex. They also generated a great deal of heat.

One Wren remembered how, in the middle of the night, an electric component of the machine flashed just as she was discreetly about to reapply some lipstick. There was a moment of dazed confusion after this thunder-flash; then the Wren’s colleague screamed. It looked as though her friend’s throat had been cut: there was a bright red line across her neck. It was in fact a line of lipstick.

In another electrical incident, a Wren received an electric shock when touching a keyboard. The laconic engineer’s report read: “Machine OK, operator earthed.”

But the oppressive heat of the machines could also be useful. It was rumoured that during those night shifts, resourceful Wren operators took the opportunity to dry their underwear.

Some Wren officers based outside of the Park were not as sensitive as the Bletchley Directorate when it came to health. Clearly not appreciating just how hard the Colossus and bombe operators were working, they made some women perform an hour’s drill after or before shifts. This was obviously madness; the women in question swiftly became exhausted and the authorities had to intervene. The officers in question made the gracious concession of excusing the Wrens the two-mile march to church on Sunday.

For some Wrens, the war was going to introduce them to a wider, more dangerous world than the secret out-stations in the Home Counties. Jean Valentine was nineteen years old when one day she saw her name had gone up on a noticeboard at Bletchley along with a few others.

She was told that she had been selected to be sent abroad for codebreaking duties, but the authorities were not at liberty at that stage to say where. All they required was that Jean seek permission from her father, because she was under the age of twenty-one, the then legal age of majority. Jean was an only child and was sure that her father would be horrified by the idea of the posting. He was not. He gave full permission, telling Jean that in war, everyone had to do their duty.

There was a six-week voyage through U-boat-infested waters and then, for Jean, the first sight of a new realm that would change the course of her life. She and her fellow volunteers were in Colombo, Ceylon. It is difficult to imagine a starker contrast to the sombre grey stone and sober hills of Perth. She gazed at a new world of rich colour and overwhelming scent.

She was there to work on Japanese codes. And she did so in an altogether more attractive kind of wooden hut—slatted bamboo, no blackout blinds—where in the middle of the night shift, she would be shooing away vast insects that had come in to inspect her work.

In off-duty hours, Jean and her friends would travel into the hills to the tea plantations, gazing upon a British empire that in 1945 looked absolutely immoveable. But the wider point is this: Wrens and WAAFs and ATS women seconded into the secret world had a capacity for absorbing novelty, and indeed approaching it with relish.

After all, if someone had told Jean Valentine a year previously that she would be deciphering Japanese weather reports, she would surely have been bemused. And the same went for all those women operating the bombe machines and the Colossi. They were doing something that no one else in the world was doing. They were there at the gates of the future, being given an extraordinary sneak preview. They didn’t have to be experts in the new science of programmable computing. But they did have to have an appetite for taking on fresh and wholly unknown challenges.

Indeed, admiring codebreakers looked on throughout 1944 and 1945 as the Wren Colossus operators not only became brilliantly proficient at arranging the machine settings and adjusting the tapes as they ran through, but in essence became themselves among the very first computer programmers.

For the time, it was a relatively emancipated set-up (aside from the issue of wages—women in any capacity always got paid less). Bright-spark Wrens worked alongside young Post Office technicians and languid codebreakers who seemed happy to let the women do the heavy lifting with the computer technology.

And unlike the bombe operators, the Wrens who were working the Colossi were told regularly that the work they were doing was having a huge impact on the war. The reason the authorities had previously held back was the all-encompassing adherence to secrecy, leaving Wrens with little if any idea where the codes were going, and whether all those night shifts were making any difference.

As the war progressed, the monthly briefings for Colossus were still sparse on detail but they had two effects: that of boosting morale, and also boosting intellectual curiosity about the material that the women were handling.

That youthful atmosphere could occasionally prove a strain for older codebreakers though. As Christmas 1944 loomed at Bletchley, there was one night when a couple of the Post Office engineers had stopped for a gossip in the corridor.

A Wren approached, and as she did so, one of the young men pulled a sprig of mistletoe out of his pocket and puckered up. The Wren shrieked and ran away down the corridor. It was at this point that an office door opened to reveal the furious head of section, Professor Max Newman, who was trying to focus on an especially abstruse problem.

On the whole, though, sexual harassment seemed relatively rare. Mutually consenting romance, on the other hand, was rife. Although the Wrens worked extraordinarily hard, they also managed to find time for extra-curricular diversion—and the best means of facilitating diversion was through dances.

Some Wrens were billeted at a nearby stately home—Crawley Grange—which dated back to the fifteenth century. As well as being thick with history (it was once owned by Thomas Wolsey), the house also had a ballroom. The Wrens who lived there thought it would be criminal not to use it. And the dances they hosted were very popular with the codebreakers.

There was one other factor that unified Wrens and the most abstract boffins alike, and that was a passion for the game of bridge. This card game for four people (two opposing teams of two) is, aside from anything else, notorious for generating nuclear levels of ill-will. It is also very much a contest for the sharp-witted. It was enjoyed by Wrens billeted in the marvellously grand surrounds of Woburn Abbey and it was also played with ferocious competitiveness by codebreakers such as Rolf Noskwith and Asa Briggs.

The puzzles in this section reflect not abstruse intellect, but rather a sort of boisterous lively intelligence that the Bletchley recruiters were looking for in the Wrens. There are quick-fire rounds of word and number challenges, which you should aim to complete as quickly as possible, designed not to measure intelligence as such, but rather to assess accuracy of response under pressure.

1

WHERE AM I?

Here are clues to a location. Where are you?

- a) FACE

- b) A RICE RAG

- c) REPORT

- d) REAR RIB

- e) I USE CATS

- f) YELL ROT

- g) PRAM LOFT

- h) EMIT BLEAT

2

PICK UP STICKS

Take off the sticks one at a time so that you are always taking the top one of the pile. In what order do you take them off?

3

CLOTHING COUPONS

Complete the words below by slotting in the name of an item of clothing.

- a) P A R _ _ _ S

- b) E S _ _ _ _ D

- c) W _ _ _ E V E R

- d) R E _ _ _ _ A N C E

- e) U N _ _ _ _ A B I L I T Y

- f) I N _ _ _ _ I T U R E

- g) R E _ _ _ B I S H M E N T

- h) I M _ _ _ E D

4

TON UP

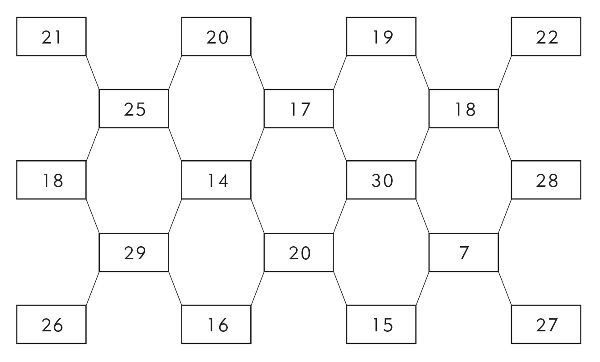

Starting at any number on the top row, move through boxes that are linked to end on the bottom row. The numbers on the way must have a combined total of exactly 100.

Which route do you take?

5

ODD ONE OUT

In each group there is an odd one out. Which is it and why?

- a) CAROLINA, GEORGIA, LUCIA, VIRGINIA

- b) BLUNDER, CARP, FLOUNDER, SKATE

- c) ARROW, CIRCLE, SQUARE, TAP

- d) EXETER, LINCOLN, PEMBROKE, WINCHESTER

- e) CHESHIRE, CHICHESTER, GLOUCESTER, LANCASHIRE

- f) ALES, CARE, HALL, WOOL

6

CREATURE CALCULATIONS

- B A T = 8

- B O A R = 14

- C A T = 9

- C R A B = 17

- R A T = 7

Every letter has a different value. What number does a COBRA equal?

7

LINK UP

Radio and telephone operators were vital links during World War II. Here you need to link a three-letter word in the left-hand column to a three-letter word in the right-hand column to create a new six-letter word.

|

ANT |

TON |

|

ASP |

RAY |

|

BAR |

HOD |

|

BET |

SON |

|

COT |

ALE |

|

DAM |

ICE |

|

EAR |

IRE |

|

FIN |

ATE |

|

HUM |

PET |

|

LEG |

HEM |

|

MET |

HER |

|

OFF |

END |

|

PAL |

OUR |

|

PUP |

THY |

|

WAS |

ROW |

8

MANY HAPPY RETURNS

Ron, Steven and Terry are talking about birthdays. They discover that the combined age of the three men and their three wives comes to exactly 150 years. Steven’s wife is one year older than he is, while Terry’s wife is two years older than Terry. Ron is twice as old as his wife. She is the same age as both Steven and Terry.

How old is Ron?

9

GOING TO THE PICTURES

The latest film releases from either side of the Atlantic were a major source of entertainment for the Bletchley Park codebreakers. Spin the letters in each left-hand square and slot a new seven-letter word reading across in each grid on the right. When you have finished, the shaded letters in Grid A will reveal a popular actor of the 1940s and the shaded letters in Grid B will tell you where he was bound in 1942.

10

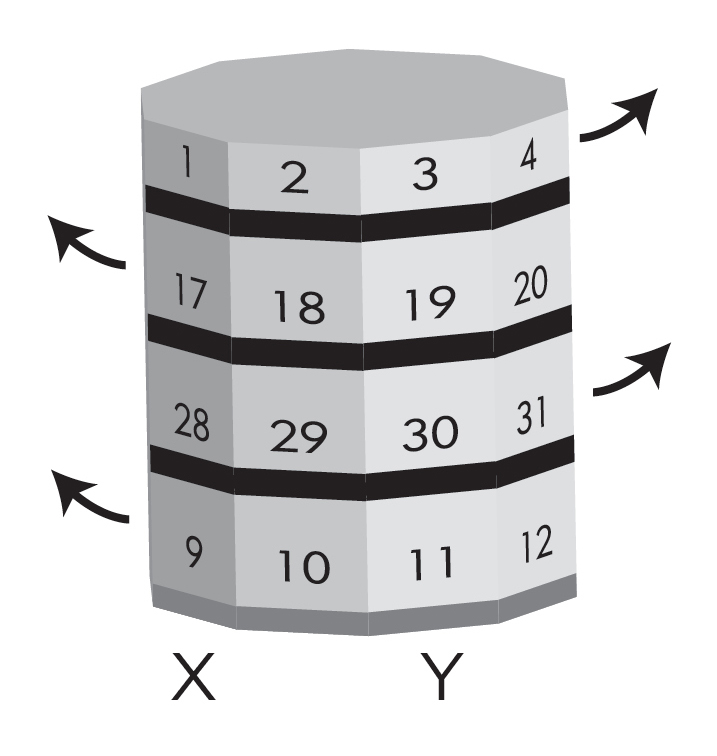

ROTATION

The four bands on this drum can move in different directions. The top band rotates in an anti-clockwise direction, as does the third band. The second and fourth bands both rotate in a clockwise direction. Each band contains eight numbers and the number sequence carries on round the drum. The column marked X shows the lowest number featured on each band. Will the total of numbers shown at column Y be greater or less after FIVE rotations of each band?

11

MIDDLE DISTANCE

Two clues, two answers. In the second answer the middle letter has moved further down the alphabet compared to the first answer, e.g. CHASE and CHOSE.

- a) Diffident * Cunning

- b) Heartbeat * Funds

- c) Performance * Disciple

- d) Beard * Trip

- e) Pariah * Survive

- f) Space * Cost

12

VOWEL PLAY

All’s fair in love and cryptology! These sentences have had certain letters changed. Try to work out the messages. Vowel play cannot be ruled out!

- a) W N D T B N R R B F R W R S F T B SN

- b) W I E R I R I E D Y E N D W E O T O N G, E R I Y U A?

- c) T H O M U R I W A U L O B A R E T I E A R M O I N S I F C A M M E N O C U T E E N, T H I L A S S W U C I M M O N A C O T I

13

POWER OF THREE

Complete the words by using the same three-letter word in each group.

|

G |

_ |

_ |

_ |

A |

N |

T |

|

|

S |

Q |

U |

_ |

_ |

_ |

Y |

||

|

R |

E |

C |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|||

|

C |

A |

_ |

_ |

_ |

A |

L |

|

|

J |

U |

_ |

_ |

_ |

E |

R |

||

|

D |

E |

S |

_ |

_ |

_ |

E |

||

|

O |

C |

_ |

_ |

_ |

U |

S |

|

|

I |

S |

O |

_ |

_ |

_ |

E |

||

|

A |

U |

_ |

_ |

_ |

S |

Y |

||

|

M |

O |

_ |

_ |

_ |

T |

U |

M |

|

C |

O |

M |

_ |

_ |

_ |

T |

||

|

P |

I |

_ |

_ |

_ |

T |

O |

||

|

A |

E |

_ |

_ |

_ |

I |

C |

|

|

M |

I |

C |

_ |

_ |

_ |

E |

||

|

P |

_ |

_ |

_ |

L |

E |

M |

14

DAYS

While not on duty on a very wet weekend, Sue starts scribbling on a pad. She notes that the words SUNDAY, TUESDAY and WEDNESDAY are made up from nine different letters of the alphabet. She gives each letter a numerical value from 1 to 9. The numbers in SUNDAY total 28, as do the numbers in TUESDAY.

WEDNESDAY has a far bigger total, 43. DAY itself has a total of 6. No two different letters have the same value. What will be the total of WET DAYS and what is the total of letters in the name SUE?

15

DOUBLE COMBINATION

In the lines of letters below the same combination of letters begins and completes each word.

|

a) |

_ |

_ |

I |

_ |

_ |

||||

|

b) |

_ |

_ |

G |

I |

B |

_ |

_ |

||

|

c) |

_ |

_ |

A |

L |

G |

_ |

_ |

||

|

d) |

_ |

_ |

I |

R |

T |

I |

E |

_ |

_ |

|

e) |

_ |

_ |

O |

C |

K |

I |

_ |

_ |

|

|

f) |

_ |

_ |

M |

P |

L |

A |

_ |

_ |

16

SEEING IS BELIEVING

- 0 appears eleven times.

- 2 appears twenty times.

- 3 appears twenty times.

- 4 appears twenty times.

- 5 appears twenty times.

- 6 appears twenty times.

- 7 appears twenty times.

- 8 appears twenty times.

- 9 appears twenty times.

There is nothing top secret or obscure about the list in which all the above things occur. How many times would the number 1 appear?

17

ALL CHANGE

Whist was a popular card game among the crews at Bletchley. Altering one letter at a time, change the word WHIST into CREWS, making a new word each time you do.

|

W |

H |

I |

S |

T |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

C |

R |

E |

W |

S |

It was a dream come true for many of the Wrens to be stationed at Bletchley, where working round the clock and to tight deadlines was key. Altering one letter at a time, change the word CLOCK into DREAM, making a new word each time you do. See if you can increase your solving time compared to the first challenge!

|

C |

L |

O |

C |

K |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

_ |

|

D |

R |

E |

A |

M |

18

SUM IT UP

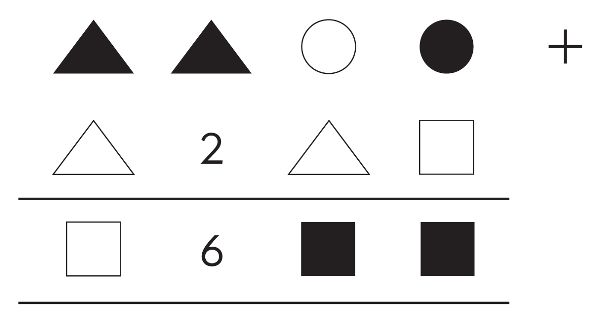

- a) Shapes have taken the place of some numbers in this sum. All the numbers are below ten and no symbol can be the same as a given number. The four digits on the top row when added together produce a smaller total than the four digits on the second row when added together. Can you solve the sum?

- b) The following sums do work. Is there a trick? You bet there is!

FIVE × EIGHT = FIVE

SIX − SEVEN = FIVE

FIVE + NINE = SEVEN

19

WORD CHAIN

Find the four-letter answers to the clues in each section. They work as a chain with the last two letters of one word starting the next.

- a) Develop, Was in debt, Modify, Irritate, Cut, Frank, Concludes

- b) Cipher, Bureau, Slide, Inspiration, Orient, Stride, Heroic

- c) Pain, Beneficiary, Metal, Sole, Musical instrument, Harvest, Pinnacle

- d) Flightless bird, Spouse, Festival, Rip, Dry, Lazy, Page

- e) Nought, Flower, Insignia, Singing voice, Roman robe, Quarry, Repair

20

CIRCULAR TOUR

Complete the circles.